The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 12: Republican China, 1912-1949, Part 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ECONOMIC INTERESTS 193

portion of the Chinese economy as a whole. Foreign and Chinese modern

enterprise both grew steadily, but neither bulked very large before 1949.

As late as 1933, 63 to 65 per cent of gross domestic product originated in

agriculture, entirely without direct foreign participation. The South Man-

churian Railway Company operated a number of experimental farms in

Manchuria, but in no part of China were there foreign-owned plantations

producing even the major agricultural export items (tea, silk, vegetable

oil and oil products, egg products, hides and skins and bristles), not to

speak of the main crops of rice, wheat, vegetables and cotton. Handicraft

production, again with no foreign participation, accounted for 7 per cent

of GDP in 1933 compared to 2.2 per cent for modern industry, in which

the foreign share was significant. Travel by junk, cart, animal and human

carriers was three times as important (4 per cent of GDP) as the modern

transport sector in which foreign-owned or operated railways and foreign

steamships appeared so prominently. China's foreign trade and even her

interport trade were carried mainly in foreign vessels, but total foreign

trade turn-over certainly never exceeded (and probably never reached)

10 per cent of GDP. If all foreign owned, controlled, operated, or in-

fluenced enterprises could, hypothetically, have been nationali2ed in 1915,

and all public and private indebtedness to foreign creditors cancelled, the

overall effect in yielding a 'surplus' that could, again hypothetically,

have been used for economic and social development would have been as

nothing compared to the potential surplus of 37 per cent of net domestic

product calculated by Carl Riskin as becoming available as a consequence

of the redistribution of wealth and income after 1949."

But the foreign businessmen and their capital were nevertheless present.

Let us now look at what forms they took and what influence they ex-

ercised.'

6

Trade

Jardine, Matheson and Company, which dated from 1832, and Butterfield

and Swire, which commenced business in Shanghai in 1867, were the most

prominent of the British trading firms. Unlike many of the 'grand old

China houses', both had survived the radical changes of the 1870s and

5 5

Carl Riskin, 'Surplus and stagnation in modern China', in Dwight H. Perkins, ed. China's

modern economy

in historical

perspective,

49-84.

56 The statistical data cited below are derived mainly from the following sources: Yen

Chung-p'ing, comp.

Chung-kuo chin-tai ching-chi shih

t'ung-chi

tzu-liao

hsuan-chi

(Selected sta-

tistical materials on modern Chinese economic history); Chi-ming Hou,

Foreign investment

and economic development

in

China,

1840-19)7; and Hsiao, China's foreign

trade

statistics, 1S64-

'949-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

I94 THE FOREIGN PRESENCE IN CHINA

1880s when the merchant importing

for

the market on his own account

was finally displaced by the 'commission merchant'. Jardine's head office

was

in

Hong Kong, with branches

in

every major port.

In

addition

to

its general foreign trade department

and

numerous agencies,

the

firm

controlled the Indo-China Steam Navigation Company (whose 41 steam-

ers were a major presence along the coast and on the Yangtze) and the large

Shanghai

and

Hongkew Wharf Company.

It

operated

a

major cotton

mill (Ewo) and

a

silk filature

in

Shanghai; represented the Russian Bank

for Foreign Trade and the Mercantile Bank of India, as well as numerous

marine and fire insurance companies and several shipping lines; and had

close ties with the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. But-

terfield was somewhat smaller, but

in

addition

to

its Shanghai headquar-

ters also maintained branches

in 14

other ports.

It

operated

the

China

Navigation Company, with

a

fleet

of

more than

60

steamers

on the

Yangtze

and

along

the

coast; managed

the

Taikoo Sugar Refining

Company and the Taikoo Dockyard and Engineering Company

in

Hong

Kong;

and

had numerous shipping and insurance agencies. (More than

200 European insurance companies were represented

by

Shanghai firms

before

the

First World War.) Gibb, Livingston and Company was also

an

old

British firm

in

China that

had

earlier kept branches

in

Canton,

Foochow, Tientsin and

at

various Yangtze ports.

In

the second decade

of the twentieth century, however,

it

had offices only

in

Shanghai, Hong

Kong

and

Foochow. Gibb devoted itself

to

the export

of

tea and silk,

general commission business

for

which

it

had many agencies, Shanghai

property,

and

shipping and insurance agencies. Founded

in

1875, Ubert

and Company was one of the first British trading firms

to

operate exclu-

sively as

a

'commission merchant', importing goods that were bought on

indentured terms by Chinese merchants.

It

also operated the Laou Kung

Mao Spinning and Weaving Company

in

Shanghai. One could go on

-

Dodwell

and

Company,

tea

exports

and

cotton piece goods imports,

shipping

and

insurance agencies,

for

example,

and

others

- but

the

in-

crease

in

German and Japanese competition facing British traders

in

the

early republic should also be noted.

Siemssen and Company,

in

Shanghai since 1856, was that port's oldest

German house and maintained offices also

in

Hong Kong, Canton, Han-

kow, Tientsin and Tsingtao. The firm was best known as engineers and

contractors

of

complete equipment

for

factories

and

railways,

for its

insurance agencies,

as

well

as for its

extensive import-export business.

Carlowitz and Company, which had commenced business

in

China in the

1840s, was perhaps the largest German firm. Shipping agents, managers of

the Yangtze Wharf and Godown Company

in

Shanghai, exporters

of

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ECONOMIC INTERESTS 195

wool, straw-braids, egg products and bristles - Carlowitz was especially

prominent as the importer of German heavy machinery, railway and

mining equipment (for the Han-Yeh-P'ing Iron and Steel Company and

its P'ing-hsiang mines, for example), and weapons (as the exclusive agents

in China for the Krupp works). Its main office in Shanghai in Kiukiang

Road was the largest building in the International Settlement in 1908.

Branches were located in Hong Kong and six treaty ports. A third im-

portant German trading firm, Melchers and Company, began business in

Hong Kong in 1866 and opened its Shanghai office in 1877. It was the

China agent for Norddeutscher Lloyd, and operated river steamers on

the Yangtze and the Chang Kah Pang Wharf Company in Shanghai.

The China branches of Mitsui Bussan Kaisha, the largest Japanese trad-

ing company, were located at Shanghai and 10 other places. In addition

to representing leading Japanese manufacturers and insurance companies,

Mitsui held agencies for several well-known British, European and

American firms. It operated its own steamer line, and owned and managed

two spinning mills (Shanghai Cotton Spinning Company and Santai

Cotton Spinning Company) in Shanghai.

In the export trade, foreign merchants had earlier been closely involved

in establishing collecting organizations to obtain supplies from the scat-

tered small producers and in making provisions for the grading, sorting

and preliminary processing of materials for export. By the late nineteenth

century, except for some processing operations (egg products, hides

and brick tea by Russian merchants, for example), most of these func-

tions had been taken over by Chinese merchants. In the case of tea,

the foreign trader almost always bought in bulk from Chinese dealers at

the ports. And although introduced by Europeans, the majority of modern

silk filatures by the beginning of the twentieth century were Chinese

owned (sometimes with European, usually Italian, managers). The role

of the Chinese merchant in the import trade, once the goods had been

landed at a treaty port, was even more prominent. With the development

of steam shipping from the 1860s, Chinese dealers in imported cotton

textiles or opium, for example, tended to by-pass the smaller ports and to

purchase directly in Shanghai and Hong Kong. While the foreign houses

were not ousted from the smaller ports, some branches were closed, and

those that remained concentrated on the collection of export goods and

the sale of more specialized imports rather than on the distribution of

staples, which was largely in Chinese hands. In this way the business of

the foreign trading firms in the early republic had become heavily concen-

trated in the major treaty ports - in the actual importation (typically as

commission agents) of foreign goods for sale to Chinese dealers and in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

196 THE FOREIGN PRESENCE IN CHINA

the exportation of Chinese goods (with some processing) from these

same places.'

7

The Standard Oil Company of New York shipped its first kerosene

to China in the 1880s where it was sold by firms such as Butterfield and

Jardine. In 1894, after the failure of lengthy negotiations with Jardine,

Matheson and Company to appoint the latter as Standard's permanent

sales agent in Asia, including China, Standard Oil undertook to establish

its own marketing organization. At first it sold its kerosene only in Shang-

hai to Chinese dealers who handled all the 'up-country' distribution.

Standard Oil resident managers were, however, soon established in the

major ports where bulk storage facilities were erected. They appointed

and bonded Chinese 'consignees' and closely supervised the sales of these

agents and their numerous sub-agents. 'In some places, as in Wuhu, for

example, the hand of the New York company extended into street ped-

dling.''

8

Specially prepared Chinese-language pamphlets and posters

advertised Standard's premium 'Devoe' brand and the cheaper 'Eagle'.

The free distribution or sale at a very low price of small tin lamps with

glass chimneys (the famous 'Mei-foo' lamp) created a market for kerosene.

By 1910 Standard Oil was shipping 15 per cent of its total exports of

kerosene to China. (A 1955 rural survey found that 54 per cent of farming

families regularly purchased kerosene.) American salesmen, many with

college degrees, who came to China under three-year agreements guaran-

teeing return passage and offering the possibility of renewal, and Chinese

assistants trained in American methods replaced the usual compradore

staff of the foreign trading firm. Travelling constantly in the interior,

required to learn the Chinese language, responsible for selecting dealers

and ensuring supplies in large territories, in perpetual conflict with

Chinese officials over local taxes, Standard's agents penetrated into

Chinese society as deeply as some of the more enterprising missionaries.

Few foreign careers in China were as colourful as that of Roy S. Anderson,

son of the missionary president of Soochow University in Shanghai and

manager of Standard Oil's Chinkiang office, who participated actively on

the republican side in the siege of Nanking in 1911 and in later years was

the trusted go-between of warlords.

Standard Oil's chief competitor in China, the Asiatic Petroleum

Company (a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell, an Anglo-Dutch alliance),

operated through a similar sales network under its own direct control.

It also sent Western salesmen into the interior, erected storage facilities

57

G. C. Allen and Audrey G.

Donnithorne,

Western enterprise

in Far Eastern

economic

develop-

ment:

China

and Japan

provides a detailed account.

58

Ralph W. Hidy and Muriel E.

Hidy,

Pioneering

in big

business,

1882-1911,

552.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ECONOMIC INTERESTS 197

in many Chinese cities, and maintained owership of the kerosene until

the actual retail sale. But Standard Oil's and Asiatic Petroleum's success

ultimately depended upon utilizing rather than replacing China's existing

commercial system. Their Chinese 'consignees', that is, wholesalers or

jobbers, were often established merchants who had other commercial

interests as well. Even the retail proprietors of Standard Oil's distinctive

yellow-fronted shops were usually prominent local dealers.

The Singer Sewing Machine Company, Imperial Chemical Industries,

which sold chemicals based on alkalis, dyes and fertilizer, and the enor-

mously successful British-American Tobacco Company also depended

upon China's traditional marketing structure to reach the final consumer.'

9

BAT was distinctive in that, in addition to importing cigarettes manu-

factured in Great Britain and America, it operated a half-dozen substantial

factories of its own in China by 1915, which escaped significant direct

taxation because of their claimed extraterritorial status. From 1913 BAT

was actively involved in promoting the cultivation of tobacco grown

from American seeds by Chinese peasants in Shantung - a foreign intru-

sion into agricultural production which was as rare in China as it was

typical in the fully colonized Asian countries. But its system of distribu-

tors and dealers directed by a network of foreign agents was merely su-

perimposed upon existing Chinese transport and local marketing facili-

ties.

And in the distribution of seed and fertilizer in Shantung - long a

tobacco-growing area - as well as in its purchase of the crop, BAT relied

primarily upon Chinese intermediaries.

Beyond the commercial structure

itself,

the overall poverty of the

Chinese economy fundamentally limited the impact of foreign merchants

and their goods. The large sales of kerosene, of cigarettes and of im-

ported cotton piece goods (before these last were ousted by the competi-

tion of cloth woven in China) were important exceptions. Even in 1936

the per capita value of China's foreign trade, including Manchuria, was

still smaller than that of any other country. If, as some analysts suggest,

neither China's share of world trade nor its per capita foreign trade were

'abnormally' low for an 'underdeveloped' country of her size and re-

sources, it is still true that foreign demand for China's agricultural and

mining exports generated only very weak 'backward linkages' (that is,

induced demand for the production of other products in the Chinese

economy), while the imported manufactured or processed commodities

went mainly to satisfy final demand and consequently generated only

weak 'forward linkages' (that is, capital or raw material inputs into

59 See Sherman G. Cochran, 'Big business in China: Sino-American rivalry in the tobacco

industry, 1890-1950' (Yale University, Ph.D. dissertation, 1975), on BAT in China.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

198 THE FOREIGN PRESENCE IN CHINA

Chinese production).

The

hope

of

economic gain

had

brought

the for-

eigner

to

China,

but

it

was

less

his

specific economic influence than

the

political

and

psychological facts

of

his

presence under privileged

con-

ditions that directly affected

the

course

of

China's modern history.

Banking

In

the

absence

of

modern financial institutions

in

China,

the

early foreign

merchant houses undertook

to

provide

for

themselves many

of

the auxil-

iary services such

as

banking, foreign exchange

and

insurance essential

to their import-export businesses.

But by the

second decade

of

the twen-

tieth century,

12

foreign banks were operating

in

China.

60

These banks

mainly financed

the

import

and

export trade

of

foreign firms. Some direct

advances were also made

to

Chinese merchants,

but

their chief impact

on

the Chinese commercial structure took

the

form

of

short-term 'chop

loans'

to the

native banks

{ch'ien-chtmng)

who in

turn lent

to

Chinese

mer-

chants. These credits

to

the

cH'ien-chuang,

which ceased with

the

Revolu-

tion

of

1911,

for a

time gave

the

foreign banks considerable leverage over

the entire money market

in

Shanghai.

6

'

They practically controlled

the

foreign exchange market

in

China.

Fluctuations

in

exchange between Chinese silver currency

and

gold

(the world standard) were frequently large,

and

foreign exchange dealings

and international arbitrage provided substantial profits

to the

foreign

banks,

especially

the

Hongkong Bank, whose daily exchange rates were

accepted

as

official

by

the entire Shanghai market.

The

foreign banks used

their extraterritorial position

to

issue bank-notes,

a

right which

the

Chinese government never conceded

but

which

it

was

powerless

to

counteract.

The

total value

of

foreign notes

in

circulation

in 1916

nearly

equalled

the

note issue

of

Chinese public

and

private banks combined.

62

Wealthy Chinese deposited their liquid assets

in

foreign banks, providing

one source

of

the

steady silver income upon which

the

banks based

their foreign exchange business.

A

more important source, however,

was

60 Chartered Bank

of

India, Australia, and China,

in

China from 1858 (head office: London);

Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, organized 1864 (head office: Hong Kong);

Mercantile Bank

of

India (head office: London); Banque

de

l'lndo-Chine,

in

China from

1899 (head office: Paris); Banque Sino-Belge, from 1902 (head office: Brussels); Deutsch-

Asiatische Bank,

in

China from 1889 (head office: Berlin); International Banking Corpora-

tion, from 1902 (head office: New York); Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij, from 1903

(head office: Amsterdam); Russo-Asiatic Bank, from 1895 (head office:

St

Petersburg);

Yokohama Specie Bank, from 1893 (head office: Yokohama); and Bank

of

Taiwan (head

office: Taihoku [now Taipei])

61

Andrea

Lee

McElderry,

Shanghai old-style

banks

(ch'ien-chuang),

1800-19)),

21-2.

62

See

Hsien

K'o,

Chin

pai-nien-lai

ti-kuo-chu-i tsai-Hua yin-hang fa-hsing chih-pi kai-k'uang

(The

issue

of

bank notes

in

China by imperialist banks

in

the past 100 years),

passim.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ECONOMIC INTERESTS 199

the major banks' role in servicing China's foreign debt and indemnity

payments, which brought an endless inflow of customs and salt receipts

and of the working capital of many railways. The major banks, moreover,

profited from the placement of indemnity and railway loans with Euro-

pean lenders. Foreign companies holding railway and mining concessions

in China were frequently affiliates of the banks; the British and Chinese

Corporation was closely linked to the Hongkong Bank, for example, as

were the German Shantung railway and mining companies to the Deut-

sch-Asiatische Bank. One study of British bankers' profits in China from

the issuance and service of foreign loans in the period 1895-1914 con-

cludes that they averaged from 4.5 per cent (for non-railway loans) to

10 per cent (for railway loans which normally included provisions for

profit-sharing and for the bank to act as purchasing agent) of the par

value of the loans.

6

'

The foreign banks lost some of their privileged position to the govern-

ment-backed banks in the 1920s, especially after 1928 but they continued

to be pre-eminent in financing foreign trade. At any time, however, their

influence on the Chinese economy outside of

the

foreign trade and govern-

ment finance sectors was negligible. Like the traders who were their

chief customers, the foreign banks affected China most by being foreign,

privileged and frequently arrogant. They of course had some links with

China's small but widespread modernizing sector. Speculation in the

Shanghai rubber market in 1910, for example, severely damaged the

Szechwan Railway Company, and its demands that these losses be covered

by the Peking government's scheme to nationalize the Canton-Hankow

railway helped precipitate the Revolution of 1911. But, overall, while

financial panics might make headlines, Shanghai and the other ports were

only loosely tied to the economy of the vast hinterland. Domination of

the modern sector, if it could be achieved by outsiders - or even by

insiders - hardly constituted control of China.

Manufacturing and mining

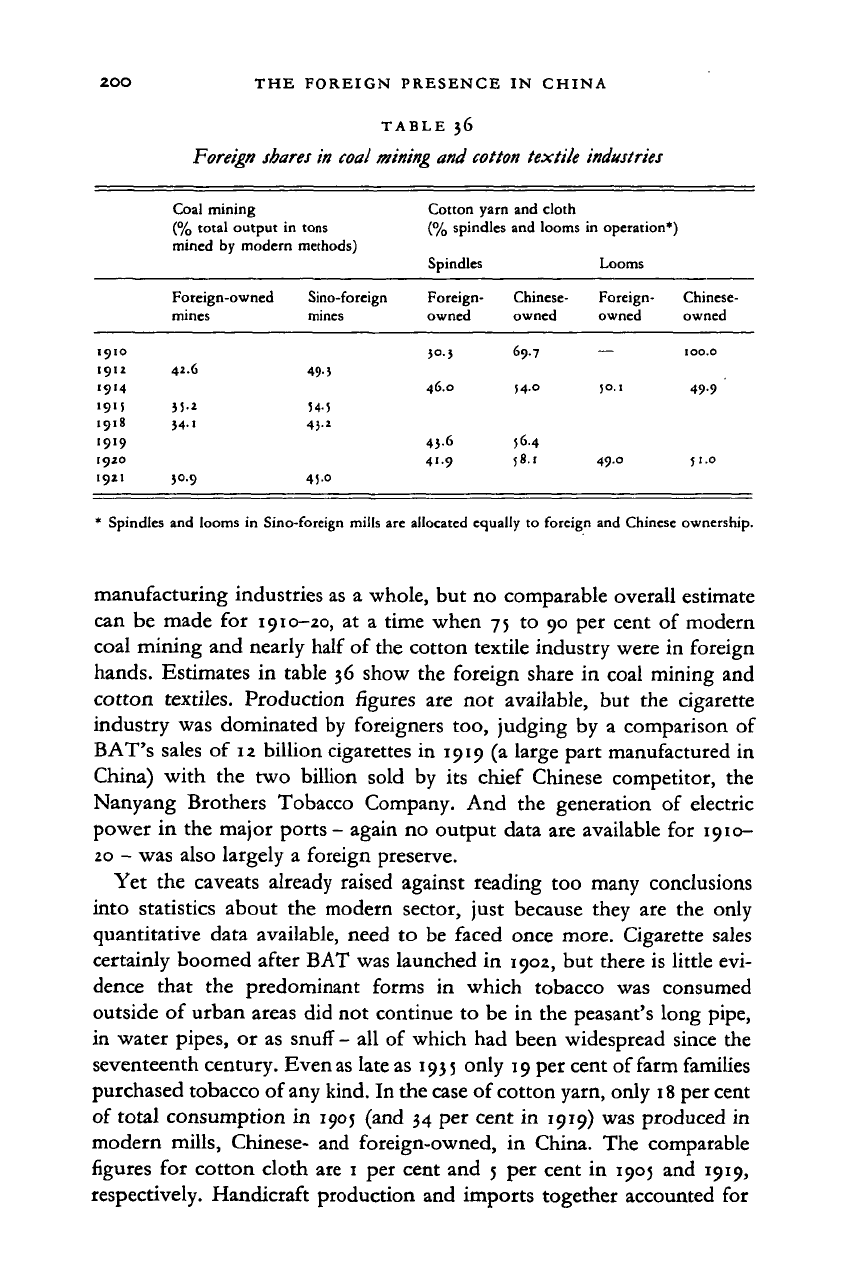

In the second decade of the twentieth century foreigners had a dominant

share in four industries which together accounted for

5

2

per cent of net

value added by modern industry in 1933: these were cotton yarn and

cloth, cigarettes, coal mining, and electric power.

64

In 1933 foreign-

owned firms produced

3 5

per cent of the total value of production by

63 C. S. Chen, 'Profits of British bankers from Chinese loans, 1895-1914', Tsing Hua

Journal

of

Chinese

studies,

N.S., 5.1 (July 1965) 107-20.

64

John

K.

Chang, Industrial development in prt-communist China:

a

quantitative analysis,

55.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

200

THE FOREIGN PRESENCE IN CHINA

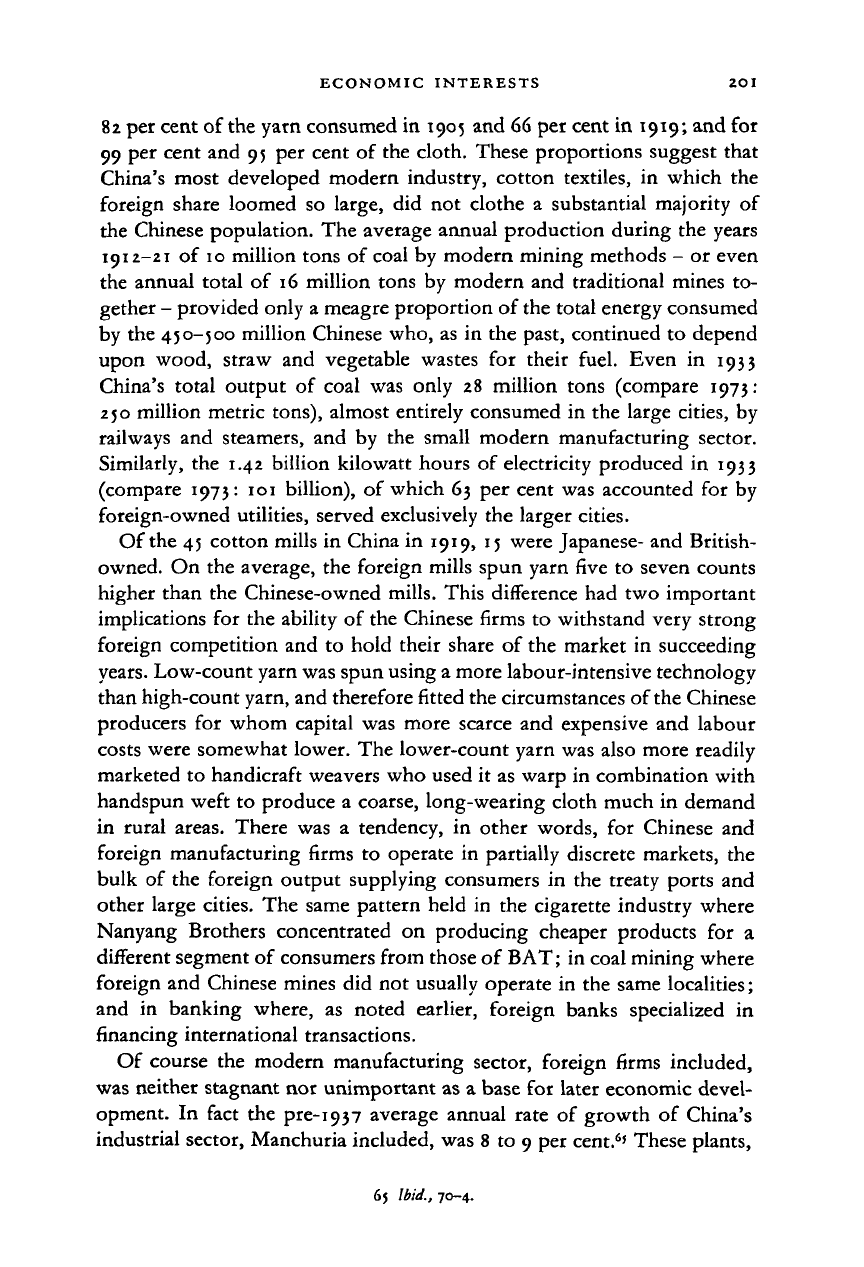

TABLE 36

Foreign

shares

in coal mining and cotton textile industries

Coal mining

(% total output

in

tons

mined by modern methods)

Cotton yarn and cloth

(% spindles and looms

in

operation*)

Spindles

Looms

Foreign-owned Sino-foreign

mines mines

Foreign- Chinese- Foreign- Chinese-

owned owned owned owned

1910

1912

1914

1915

1918

1919

1920

1921

42.6

35-*

54.1

50.9

495

54-5

43-2

4J.0

30-3

46.0

43.6

41.9

69.7

J40

56.4

58.1

JO.l

49.0

49.9

51.0

Spindles and looms

in

Sino-foreign mills are allocated equally to foreign and Chinese ownership.

manufacturing industries as

a

whole, but no comparable overall estimate

can be made

for

1910-20,

at a

time when 75

to

90 per cent

of

modern

coal mining and nearly half of the cotton textile industry were in foreign

hands.

Estimates

in

table 36 show the foreign share

in

coal mining and

cotton textiles. Production figures

are not

available,

but the

cigarette

industry was dominated by foreigners too, judging by

a

comparison of

BAT's sales

of

12 billion cigarettes in 1919 (a large part manufactured in

China) with

the

two billion sold

by its

chief Chinese competitor,

the

Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company. And

the

generation

of

electric

power

in

the major ports

-

again no output data are available for 1910-

20

-

was also largely

a

foreign preserve.

Yet the caveats already raised against reading too many conclusions

into statistics about

the

modern sector, just because they are

the

only

quantitative data available, need

to

be faced once more. Cigarette sales

certainly boomed after BAT was launched in 1902, but there is little evi-

dence that

the

predominant forms

in

which tobacco

was

consumed

outside

of

urban areas did not continue to be in the peasant's long pipe,

in water pipes,

or

as snuff

-

all

of

which had been widespread since the

seventeenth century. Even

as

late as 1935 only 19 per cent of farm families

purchased tobacco of any kind. In the case of cotton yarn, only 18 per cent

of total consumption in 1905 (and 34 per cent in 1919) was produced in

modern mills, Chinese- and foreign-owned,

in

China. The comparable

figures for cotton cloth are 1 per cent and 5 per cent

in

1905 and 1919,

respectively. Handicraft production and imports together accounted

for

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ECONOMIC INTERESTS 201

82 per cent of the yarn consumed in 1905 and 66 per cent in 1919; and for

99 per cent and 95 per cent of the cloth. These proportions suggest that

China's most developed modern industry, cotton textiles, in which the

foreign share loomed so large, did not clothe a substantial majority of

the Chinese population. The average annual production during the years

1912-21 of 10 million tons of coal by modern mining methods - or even

the annual total of 16 million tons by modern and traditional mines to-

gether - provided only a meagre proportion of the total energy consumed

by the 450-500 million Chinese who, as in the past, continued to depend

upon wood, straw and vegetable wastes for their fuel. Even in 1933

China's total output of coal was only 28 million tons (compare 1973:

250 million metric tons), almost entirely consumed in the large cities, by

railways and steamers, and by the small modern manufacturing sector.

Similarly, the 1.42 billion kilowatt hours of electricity produced in 1933

(compare 1973: 101 billion), of which 63 per cent was accounted for by

foreign-owned utilities, served exclusively the larger cities.

Of the 45 cotton mills in China in 1919, 15 were Japanese- and British-

owned. On the average, the foreign mills spun yarn five to seven counts

higher than the Chinese-owned mills. This difference had two important

implications for the ability of the Chinese firms to withstand very strong

foreign competition and to hold their share of the market in succeeding

years.

Low-count yarn was spun using a more labour-intensive technology

than high-count yarn, and therefore fitted the circumstances of the Chinese

producers for whom capital was more scarce and expensive and labour

costs were somewhat lower. The lower-count yarn was also more readily

marketed to handicraft weavers who used it as warp in combination with

handspun weft to produce a coarse, long-wearing cloth much in demand

in rural areas. There was a tendency, in other words, for Chinese and

foreign manufacturing firms to operate in partially discrete markets, the

bulk of the foreign output supplying consumers in the treaty ports and

other large cities. The same pattern held in the cigarette industry where

Nanyang Brothers concentrated on producing cheaper products for a

different segment of consumers from those of BAT; in coal mining where

foreign and Chinese mines did not usually operate in the same localities;

and in banking where, as noted earlier, foreign banks specialized in

financing international transactions.

Of course the modern manufacturing sector, foreign firms included,

was neither stagnant nor unimportant as a base for later economic devel-

opment. In fact the pre-1937 average annual rate of growth of China's

industrial sector, Manchuria included, was 8 to 9 per cent.

6

' These plants,

65

Ibid.,

70-4.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2O2 THE FOREIGN PRESENCE IN CHINA

moreover, made important contributions

to

China's post-1949 economic

growth. Among the less obvious benefits,

the

inherited small-scale engin-

eering plants

in

Shanghai and elsewhere contributed significantly to resolv-

ing

the

economic difficulties

of

the 1960s.

66

What

is

questionable

is the

view that

the

conspicuous foreign role

in

the modern manufacturing sector

was a

primary cause

of

either China's

overall economic backwardness

or of

the debilitating economic inequali-

ties which characterized pre-1949 China.

The

economic

consequences

-

with respect

to

both development

and

distribution

- of

whether

a

plant

was foreign-owned

or

Chinese-owned were minuscule

as

compared with

the primary political

and

psychological effects

of the

privileged,

and in

the case

of

modern industry sometimes dominant, foreign presence

in

China. Studies

of

pre-1949 industry show

not

only

the

impressive rate

of growth cited above,

but

also strong evidence that Chinese-owned

enterprises grew

at

least

as

fast

as

foreign manufacturing firms.

67

The

long-term trend

in the

twentieth century, though imperfectly known,

suggests

a

gradual increase

in

the Chinese share

of

capitalization and out-

put

in

foreign trade

and

banking

as

well

as in

industry.

To the

extent

that

the

traditional sector

of the

economy (handicraft manufacture,

for

example)

was

undermined

by

modern industry,

the

Chinese-owned

modern sector

was

primarily responsible because

it

mainly served

the

geographically

and

technologically discrete rural market, whereas

the

foreign plants' customers were more likely

to be

relatively well-to-do

urban residents.

In the

long

run

perhaps

the

most important aspect

of

foreign manufacturing

was its

transfer

to

China

of

modern industrial

technology

in the

form

of

machinery, technical skills

and

organization.

This 'demonstration effect' also operated

in the

financial

and

commercial

sectors where Chinese modern banks

and

insurance companies became

increasingly important after 1911

and

Chinese foreign trading companies

modelled

on

their foreign rivals began

to be of

some significance

in the

1920s.

Foreign manufacturing firms benefited 'unfairly' from their extrater-

ritorial status, from their ability

to

escape some direct taxation

and the

especially heavy hand

of

Chinese officialdom, from their access

to

foreign

capital markets,

and

sometimes from better management

or

improved

technology. This privileged status,

as

well

as

their conspicuousness

and

hauteur,

fed the

burgeoning nationalism

of

twentieth-century China

which expressed itself

in

'buy-Chinese' sentiments. Chinese-owned firms

66

See

Thomas

G.

Rawski,

'The

growth

of

producer industries, 1900-1971',

in

Perkins,

ed.

China's

Modern

Economy,

203-34.

67 Hou,

Foreign

investment,

138-41.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008