Scragg Donald (Edited). Edgar, King of the English 959-975: New Interpretations (Pubns Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

234 CATHERINE E. KARKOV

In the miniature accompanying the benediction (Fig. 11.2) the use of outline

drawing to depict both the church and the congregation conveys the identifica-

tion of the one with the other, albeit in a way different from that used in the New

Minster Charter frontispiece.

45

Before turning once again to the iconography of the frontispiece, it should be

noted that there are some significant similarities between the texts of the ordo

and that of the charter that would certainly not have been lost on Æthelwold.

The idea that Christ is present in the church and the congregation expressed in

the ordo and the blessing in the Benedictional is also very much a part of the

charter. The charter records the granting of the New Minster to Christ by Edgar.

Christ is present in figural form in the frontispiece, where he is shown receiving

his newly cleansed church. He is present symbolically in the large chi-rho which

prefaces the words ‘Omnipotens totius machinae conditor’

46

on folio 4 recto.

His presence is invoked a final time in the dating clause that appears directly

above the king’s subscription on folio 30 recto,

47

and by the sign of the Holy

Cross that accompanies the names of most of the witnesses. A number of these

crosses, most importantly the large cross preceding Edgar’s subscription, are

filled in with gold ink and, like the gold letters of the text of the charter, they

function as signs of the light of heaven infusing both the book and the earthly

world of which it is a part. The golden crosses, chrismons and letters, in the

words of Herbert Kessler, negotiate the space ‘between the world of matter and

the world of spirit’,

48

as do the sacred texts in which they are usually found and

the liturgical ceremonies to which those texts are usually connected.

The dedication

ordo was also, as we have seen, centred on the process of

cleansing or baptism. The purification and exorcisms enacted in the ordo are

as concerned with expulsion and judgement as they are with entrance and the

blessing of the newly cleansed church and everything associated with it. Take,

for example, one of the texts for the cleansing of salt:

Exorcizo te creatura salis . per deum uiuum . per deum uerum . per deum

sanctum . per deum qui te per eliseum prophetam in aquam mitti iussit ut

sanaretur sterelitas aque . ut effeciaris sal exorcizatum in salutem credentium

. ut sis omnibus te sumentibus sanitas anime et corporis et effugeat atque

discedat ab eo loco quo aspersus fueris omnis fantasia et nequitia uel uersutia

Spirit, in which God, the Holy Trinity, might deign to dwell continuously, and after the

running out of the excursion of this life of labouring, you might merit to come successfully

to eternal joy. Amen.’ Prescott, p. 19, quoting Deshman, Benedictional, p. 141.

45

Deshman, Benedictional, pp. 142–5, has explored the baptismal symbolism of both the

blessing and the miniature.

46

‘Almighty creator of the whole order of creation’.

47

‘Anno incarnationis dominicȩ .dcccclxvi. scripta est h’u’ius priuilegii singrapha his tes-

tibus consentientibus quorum inferius nomina ordinatim caraxantur.’ (‘The document of

this privilege was written in the year of the Lord’s incarnation 966, with these witnesses

in agreement whose names are written below’.)

48

Kessler, Seeing Medieval Art, p. 29.

FRONTISPIECE TO THE NEW MINSTER CHARTER 235

diabolice fraudis omnisque spiritus immundus adiuratus per eum qui uentures

est iudicare uiuos et mortuos et saeculum per ignem.

49

Or the antiphon ‘Asperges me domine ysop et mundabor lauabis me et super

niuem dealbabor.’

50

The emphasis in the ordo on the purification of the church and the driving

out of evil from everything associated with it is paralleled in the frontispiece by

the symbolism of Mary’s palm

51

and Peter’s key, and in the text of the charter

by the latter’s repeated references to the cleansing of the New Minster by the

driving out of the secular canons. The expulsion of the canons is commemorated

symbolically in the prologue and first four chapters of the charter in the lengthy

account of the fall of the rebel angels and the fall of Adam and Eve.

52

Here, as in

the ordo, the community is portrayed as the Lord’s chosen people. Men replaced

angels, grew corrupt, and are now replaced by the reformed community. Chapter

VI, the chapter that provides a transition from the proem to the dispositive

section of the charter begins with the words ‘hinc ego Eadgar’ (‘hence I Edgar’)

signalling the direct and causal relationship between the events. The expulsion

of the canons is also recorded literally in chapter VII, where Edgar is described

as ‘vicarius christi’ (‘the vicar of Christ’), a term used later in the charter for

the abbot.

53

Rumble suggests that it is as vicar of Christ that Edgar is depicted in

the charter’s frontispiece.

54

But the dual use of the term also suggests that Edgar

is to be associated with the Minster itself, that his figure may literally negotiate

the space between the monastery under the rule of the abbot, and the kingdom

of heaven under the rule of Christ. This is further suggested in the charter by

the equation of the monastery with heaven as earthly and heavenly paradises

respectively,

55

an equation that is perhaps furthered by the lush acanthus orna-

ment and golden bars of the frame of the frontispiece. This is not the sort of

language one usually finds in a charter, but it is an important part of dedication

and consecration ceremonies in which the cleansing of the monastery revealed

it to be a type of paradise.

49

Egbert, p. 39: ‘I exorcize you creature of salt through the living God, through the true

God, through holy God, through the God who commended you through the prophet Elijah

to be thrown into the water so that the sterility of the water might be cured, so you, ex-

orcized salt, might bring about the salvation of those believing and so you might be for

everyone who partakes of you health of the soul and body and so that every phantom and

evil and craftiness of diabolical fraud and every impure spirit having been adjured may

flee and depart from this place where you will have been sprinkled. Through he who is

about to come to judge the living and the dead through fire.’

50

Egbert, p. 41. ‘Thou shalt sprinkle me, Lord, with hyssop and I shall be cleansed, thou

shalt wash me and I shall be made whiter than snow’ (Ps. 50:9).

51

See Deshman, Benedictional, p. 199 on the complex symbolism of the palm.

52

On the fall of the angels see D. F. Johnson, ‘The Fall of Lucifer in Genesis A and Two

Anglo-Latin Royal Charters’, JEGP 7 (1998), 500–21.

53

Ch. 14; Rumble, Property and Piety, p. 88.

54

Rumble, Property and Piety, p. 81, n. 46; see also p. 70.

55

In Chapter VI the monastery is identified as the Lord’s ploughland (‘Domini cultura’), and

in Chapter XVIII as Christ’s ploughland (‘Christi cultura’).

236 CATHERINE E. KARKOV

From its original foundation in the early tenth century, the New Minster was

a uniquely royal church. Possibly the vision of King Alfred,

56

the forerunner

of the tenth-century minster is likely to have been the monasteriolum given to

Grimbald of Saint-Bertin, who arrived in England in 887 and died in 901 prior

to the completion of the new foundation.

57

The relics of Grimbald and St Judoc

(a Breton prince who became a priest and hermit) became the principle relics

of the early church. The earliest grant of land to the new foundation may be

preserved in a charter of 901 (S 1443; Miller no. 2) which records the granting

by Bishop Derewulf and the Old Minster community of a ‘ƿind circan’ (‘wind

church’) and stone dormitory to Edward the Elder in exchange for the church of

St Andrew and its worthy. I mention the grant because of the possibility that the

wind church might have been an abandoned church (as opposed to a ‘thatched’

or ‘wattled’ church),

58

a motif that occurs regularly in legends of foundation

or refoundation on the continent,

59

and one which interestingly prefigures the

abandoning of the church by the secular canons prior to the 964 refoundation. In

both instances we are dealing with spaces that, while neglected, are already ‘in-

trinsically and essentially sacred’.

60

According to the charter, Edward acquired

the new land in order to build a church for the salvation of his soul and that of

his venerable father, King Alfred.

61

A second charter of the same year (S 365;

Miller no. 4) calls for prayers of intercession to be said daily for Edward, the

venerable Alfred and their ancestors.

62

The New Minster very quickly became

a dynastic mausoleum with the translation of Alfred’s body to the new church

shortly after its construction,

63

and the subsequent burial there of Ealhswith in

902, Æthelweard in the early 920s and Edward and his son Ælfweard in 924.

Eadwig, Edgar’s brother (d. 959), was the last of the West Saxon kings to be

buried there. Edgar, like his father Edmund, would eventually be buried at Glas-

tonbury, possibly due to the politics of succession rather than his own wishes

– although obviously we have no way of knowing this for certain.

64

The New

56

M. Biddle. ‘Felix Urbs Winthonia: Winchester in the Age of Monastic Reform’, Tenth-

Century Studies, ed. D. Parsons (London and Chichester, 1975), pp. 123–40, at 128–31;

Keynes, Liber Vitae, pp. 16–18; M. Hare, ‘The Documentary Evidence in 1086’, The

Golden Minster: The Anglo-Saxon Minster and Later Medieval Priory of St Oswald at

Gloucester, ed. C. Heighway and R. Bryant (york,

1999), pp. 33–46, at 34; but see also

Miller, Charters of the New Minster, p. xxv.

57

Keynes, Liber Vitae, p. 17, describes the identification of the monasteriolum as a fore-

runner of the New Minster as having been made ‘in retrospect’.

58

WinchNM, p. 6, citing P. R. Kitson, A Guide to Anglo-Saxon Charter Boundaries, forth-

coming.

59

Remensnyder, Remembering Kings Past, pp. 40, 47, 48.

60

See the discussion by Remensnyder, Remembering Kings Past, p. 44.

61

For mine saule haelo mines þæs arwyrðan fader.

62

Pro me et venerabilis patre et auibus meus cotidie orations fiant et intercessiones.

63

As WinchNM points out, S 365 implies that Alfred’s body might already have been buried

in the ‘wind-church’.

64

One wonders why he was not buried at Æthelwold’s Winchester since the two had worked

so closely together in life. It may be simply that he wanted to be buried near his father

and in one of the houses associated with the origins of the reform. It could also be that

FRONTISPIECE TO THE NEW MINSTER CHARTER 237

Minster was clearly by Edgar’s day a church associated with the bodies of the

West Saxon royal family that it had come to house. The history of the abbey

contained in the later Liber Vitae shows that the community was very aware of

its royal foundations and its royal burials. It is highly unlikely that Edgar would

have been unaware of how his actions of refoundation paralleled those of the

original founders.

Burial

w

as something that seems to have set the New Minster apart from the

Old Minster. While royal burials had taken place in the cemetery of the Old

Minster, they were not contained within the body of the church prior to the

construction of the west-work, which was not begun until 971.

65

The people of

Winchester also seem to have had the right of burial in the New Minster cem-

etery. That right is not recorded until the move to Hyde Abbey in 1110, but by

then it was understood as having been of long-standing tradition.

66

In contrast

to the Old Minster, the bishop’s church, the New Minster was identified not

only with the bodies it contained, but also with the king and the people of the

city.

67

There is certainly a distinct difference in the plans of the two churches.

The New Minster was over twice as long as the Old Minster, with a wide nave

flanked by side aisles and a spacious eastern transept.

68

It was intended from

the start to hold a large congregation. The Old Minster, prior to the rebuilding

in the 980s, was small and crowded, with a nave only about forty feet long

and small eastern porticus rather than a transept. Even after its rebuilding it

remained a very narrow church, its entire body only about as wide as the nave

of the New Minster (without its side aisles). The latter thus seems to have been

from the first intimately associated with its congregation, the people of the royal

burh which was itself intimately associated with the rise of the West Saxon

dynasty; just as it was intimately associated with the bodies of the West Saxon

kings and princes. All churches are equated with the congregations they house,

but in the case of the New Minster the associations seem to have been made

particularly apparent. No other Anglo-Saxon church contained so many royal

bodies, presumably in marked graves,

69

and this was as much a part of the

original conception of what the church should be as was its impressive size. To

see the impressive body of Edgar in the New Minster charter as a sign of this

royal foundation with its royal burials and its large congregation is perfectly in

keeping with the purpose and symbolism of the New Minster itself, especially

as he is flanked by the Minster’s new patron saints.

This

type

of symbolism is in no way exclusive to the New Minster Charter.

Glastonbury was chosen by his eldest son Edward, who would have organized the burial,

because Æthelwold supported the cause of his brother Æthelred. I thank the late Patrick

Wormald for this last suggestion.

65

The west-work was built above the cemetery, and after its construction burials are known

to have taken place within it. Biddle, ‘Felix Urbs Winthonia’, p. 138.

66

M. Biddle, Winchester in the Early Middle Ages (Oxford, 1976), p. 314.

67

WinchNM, p. xxvii.

68

See the plan in Biddle, ‘Felix Urbs Winthonia’, p. 130.

69

The Liber Vitae (fol. 5), for example, records that Edward’s burial was to the right of the

high altar (Keynes, Liber Vitae, p. 19), implying that it must have been marked visually.

238 CATHERINE E. KARKOV

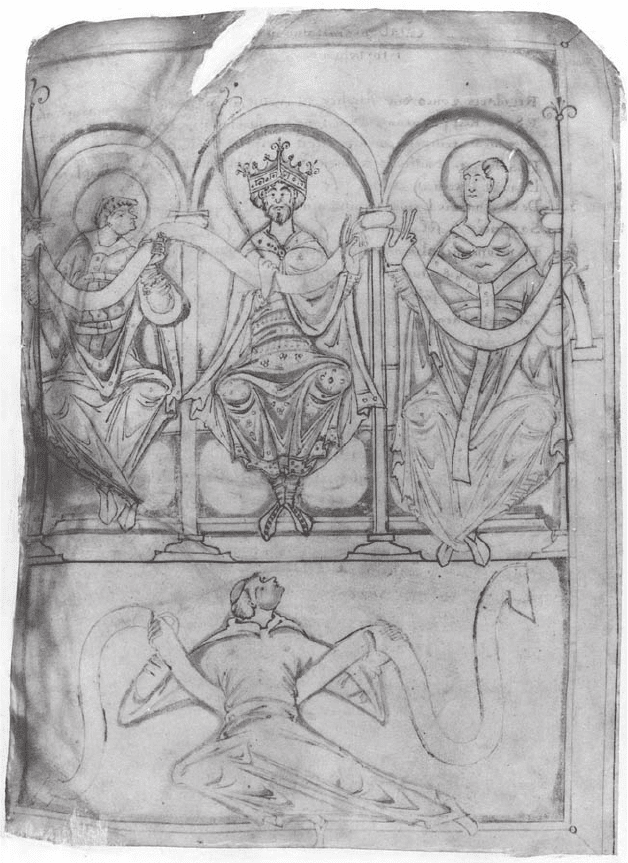

Fig. 11.3 London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius A.iii, fol. 2v.

© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved.

Disclaimer:

Some images in the printed version of this book

are not available for inclusion in the eBook.

To view the image on this page please refer to

the printed version of this book.

FRONTISPIECE TO THE NEW MINSTER CHARTER 239

The visualization of the church as a living body is generally an important part of

the art associated with the reform, especially art produced under the patronage

of, or in association with, Bishop Æthelwold. It is conveyed by the use of outline

drawing to suggest the unity of church and congregation in the miniature for the

blessing of a church in his Benedictional (Fig. 11.2).

70

It is evident in the depic-

tion of St Swithun on folio 97 verso of the same manuscript,

71

in which Swithun

is literally a human column, a living part of the architecture. It is evident also

in the story of St Æthelthryth and the refoundation of Ely, in which the legal

possession of the saint’s body and her church were one.

72

This took material

form in the creation and display of the golden statues of Æthelthryth and the Ely

virgins donated to the church at Ely by abbot Byrhtnoth sometime before his

death in 999 – a literal making visible of the bodies of the women, the human

foundations on which the refoundation rested.

F

or

Æthelwold, Edgar’s body might have come to stand in a similar way not

just for the man himself, but for the body of the church he refounded. Even-

tually it came to stand for the reform itself. Edgar is depicted as a co-author

of the reform in the miniature that prefaces the Regularis Concordia in the

Tiberius A.iii manuscript (Fig. 11.3). The manuscript was produced at Christ

Church Canterbury in the middle of the eleventh century, but it is believed by

some art historians to be a copy of a reform period original,

73

possibly designed

by Æthelwold himself.

74

It depicts King Edgar enthroned between two figures

usually identified as Bishop Æthelwold and Archbishop Dunstan.

75

Their bodies

are united by the scroll which may represent the Rule and/or the process of its

production.

76

Below them is a monk who has girded his loins with the ‘faith and

good works’ described in the text.

77

All eyes are on Edgar who stares fixedly out

at us like Christ in majesty, or like the imperial portraits of Otto III. Recently I

compared this image of Edgar to the famous portrait of Otto on folio 16 recto of

70

In a talk delivered to a meeting of the Society of Antiquaries in Oxford (October, 2004),

the Biddles commented on how closely the depiction of the church in the miniature

accords with what is known of the architecture of the Old Minster.

71

Illustrated in Deshman, Benedictional, pl. 32.

72

S. Ridyard, The Royal Saints of Anglo-Saxon England: A Study of West Saxon and East

Anglian Cults (Cambridge, 1988), ch. 6; C. E. Karkov, ‘The Body of St Æthelthryth:

Desire, Conversion and Reform in Anglo-Saxon England’, The Cross Goes North:

Processes

of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300–1300, ed. M. Carver (york, 2002),

pp. 398–411.

73

See, e.g. J. J. G. Alexander, ‘The Benedictional of St Æthelwold and Anglo-Saxon

Illumination in the Reform Period’, Tenth-Century Studies, ed. D. Parsons (London and

Chichester, 1975), pp. 169–83, at 183; R. Deshman, ‘Benedictus Monarcha et Monarchus:

Early Medieval Ruler Theology and the Anglo-Saxon Reform’, FS 22 (1988), 204–40, at

207–10 and 219.

74

Deshman, ‘Benedictus’, 210.

75

But see B. Withers, ‘Interaction of Word and Image in Anglo-Saxon Art, II: Scrolls and

Codex in the Frontispiece to the Regularis Concordia’, OEN 31.1 (1997), 38–40 for

alter

native possibilities.

76

Withers, ‘Interaction of Word and Image’. Withers goes further and suggests that the scroll

is assign of oral rather than written production (p. 39).

77

Deshman, ‘Benedictus’, 205.

240 CATHERINE E. KARKOV

the Aachen (or Liuthar) Gospels (Aachen, Cathedral Treasury), in which a scroll

carried by symbols of the four evangelists divides the emperors head from his

body.

78

The portrait was central to Kantorowicz’s thesis of the king’s two bodies:

the body itself representing the mortal king and the staring frontal head crowned

by the hand of God, his eternal and divinely granted authority.

79

I argued that

the scroll in the Edgar portrait functioned much the same way, marking the two

natures of Edgar’s kingship: the human and the sacral. I now think, however,

that that interpretation is in some need of modification. I do think that the scroll

does indicate that Edgar has two bodies, but I would suggest that they are not

human and sacral, so much as individual and corporate. We should note that

the same scroll that separates Edgar’s head from his body also separates the

heads of Æthelwold and Dunstan from their bodies. It serves, I would argue,

to identify them as both the individuals who initiated and oversaw the reform

and who produced the Regularis Concordia, and as the corporate body of the

reformed church itself, a church comprised in this monastic agreement of the

king, bishop, archbishop and the monastic community – the latter represented

by the monk in the lower half of the page. There is, of course, an eternal nature

to the symbolism, but in this manuscript it is connected with the eternal au-

thority of the Rule and the reformed church rather than with sacral kingship.

This image has a very different manuscript context than the gospelbook portrait

of Otto III.

The

por

trait of Edgar in the New Minster charter prefaces a charter, a man-

uscript that maps and describes not the topography or structure of the New

Minster, but its purification, one that lays out the interdependence of the mon-

astery and the king, and one that likens the king’s relationship to Christ to

the abbot’s relationship to Christ. Like the Tiberius A.iii drawing, it is not just

about Edgar’s exalted position, but about his relationship to the living bodies

that make up the community for whom the charter was written and decorated,

and the living bodies of the congregation for whom the church was built, and

who, at least on special occasions, would likely have seen the charter displayed

on the altar. For both groups the frontispiece would have visualized their own

dual history as a royal foundation and as a covenant people with God. Edgar’s

body was one with which they could all identify in offering up themselves to

Christ. The descent of the divine towards Edgar’s body was also one with which

they could identify, both in terms of their desire to be united with Christ in the

future, and in their experience of baptism, the moment at which they too would

have been touched by the Holy Spirit. In baptism, Christ was not just himself,

but ‘his members baptized into his ecclesiastical body’.

80

For the New Minster

faithful looking at the frontispiece Edgar too was visually and symbolically a

78

Illustrated in Karkov, Ruler Portraits, fig. 15.

79

E. Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princ-

eton, NJ, 1957), pp. 61–78.

80

The quotation is from Deshman, Benedictional, p. 145. For the ways in which this sym-

bolism is brought out in the Benedictional’s miniatures of the Baptism of Christ and the

dedication of a church see ibid., pp. 142–5.

FRONTISPIECE TO THE NEW MINSTER CHARTER 241

type of ecclesiastical body, a corporate body representing this particular church

in which they were all united and in which they had all been made ‘as living

stones built up, a spiritual house, a holy priesthood, to offer up spiritual sacri-

fices’ (I Peter 2:5). The image was a perpetual reminder that they were just what

the words of the charter said they were, a people ‘collected together’ by God

under Edgar.

12

The Laity and the Monastic Reform

in the Reign of Edgar

ALEXANDER R. RUMBLE

O

F the two main divisions within Anglo-Saxon society, ecclesiastical and lay,

the latter made up the vast majority of the population. However, because

of the purpose and bias of the surviving written sources relating to the tenth-

century monastic reform, lay people were only very selectively mentioned in

them, mainly as either benefactors or despoilers of the endowment. We should

not think from this that the rest of the lay population were unaware of, or imper-

vious to, the events and consequences of the reform and there are clear indica-

tions that some individuals, families, and groups were greatly affected in one

way or another.

The

refor

m could not have succeeded without the power and authority of the

king and his officials. There is documentary evidence that other members of the

laity gave support of a physical as well as a financial nature to the process of

re-establishing the monastic life. Some of these may have been merely obeying

orders from their superiors, but others may have been genuinely moved by re-

ligious sentiment to help the monks and nuns in their pursuit of a form of mo-

nastic life closer to the Regula S. Benedicti.

According

to Wulfstan the Cantor’s Vita S. Æthelwoldi, the important king’s

thegn Wulfstan of Dalham was sent by Edgar [in 964] to supervise the expulsion

of the secular priests from the Old Minster, Winchester and their replacement

by monks:

The king also sent there with the bishop one of his agents, the well-known

Wulfstan of Dalham (quendam ministrorum suorum famosissimum, cui nomen

erat Wulfstan æt Delham), who used the royal authority to order the canons to

choose one of two courses: either to give place to the monks without delay or

to take the habit of the monastic order. Stricken with terror, and detesting the

monastic life, they left as soon as the monks entered …

1

Wulfstan of Dalham was described in the Liber Eliensis as sequipedus ‘close

companion’ of King Eadred, and so by the reign of Edgar was already an expe-

1

Wulfstan, Vita S. Æthelwoldi, ch. 18. See Lapidge and Winterbottom, WulfstW, pp. 32–3.

THE LAITy AND THE MONASTIC REFORM 243

rienced official.

2

He was a royal reeve and probably the steward in East Anglia

of the estates of the queen mother Eadgifu.

3

His locational byname could be

either from Dalham in Suffolk or Dalham in Kent, as he appears to have had

connections with both shires.

4

He was given the Latin designation discifer in

S 768 (AD 968) – equivalent to OE disc-þegn, and was called prefectus in S 796

(AD

974).

5

Although he would have been obliged to act in accordance with

royal commands, it is also significant that later he was personally recorded as a

benefactor of the monasteries at both Ely and Bury St Edmunds.

6

He subscribed

to documents 958 x 974, probably including the hugely important New Minster

Refoundation Charter of 966.

7

It is very probable that the physical expulsion of the secular clergy from the

New Minster was also effected by lay royal officials, but on that occasion by

those employed by the queen, Ælfthryth, if her subscription to the Refoundation

Charter is to be taken literally.

+ I, Ælfthryth, the legitimate wife of the aforementioned king. with the king’s

approval establishing the monks in the same place, by the sending of my am-

bassador (mea legatione monachos eodem loco rege annuente constituens),

have made the mark of the Cross.

8

The date of this action was probably between 964 and 966, that is, after

Ælfthryth became queen by her marriage to Edgar and the date of this witness-

list.

9

Although ASC A refers to the expulsion of the secular priests from the

New Minster s.a. 964, in the same annal as its reference to the reform of the

Old Minster and Chertsey and Milton, its account should probably be seen as

an over-simplification of an extended process.

10

Some of Edgar’s ealdormen and their families were also recorded as patrons

of the reform. Æthelwine ‘Dei Amicus’, ealdorman of East Anglia, was the

founder of Ramsey (in 966).

11

Æthelmær, the son of Ealdorman Æthelweard

of the Western Provinces who succeeded his father c. 1012, founded Cerne

2

LE, II.xxviii, p.102.

3

Lapidge and Winterbottom, WulfstW, p. 32, n. 2.

4

C. R. Hart, The Early Charters of Northern England and the North Midlands (Leicester,

1975), p. 379. See respectively A. D. Mills, A Dictionary of British Place-Names (Oxford,

2003), p. 147 and J. K. Wallenberg, The Place-Names of Kent (Uppsala, 1934), p. 119.

5

Burt, no. 23; and Malm, no. 28 (which records the restoration of an alienated monastic

estate).

6

Hart, Early Charters of Northern England and the North Midlands, p. 379.

7

Rumble, Property and Piety, no. 4, at p. 97, n. 164.

8

Rumble, Property and Piety, no. 4, at pp. 93–4.

9

For an apparently genuine diploma issued in 964 by King Edgar in favour of his queen

Ælfthryth, see S 725; Abing, no. 101. For the credibility of the Refoundation Charter’s

witness-list, see Rumble, Property and Piety, p. 92, n. 125 and p. 93, n. 128.

10

Bately, MS A, pp. 75–6.

11

On Æthelwine, see C. Hart, ‘Athelstan Half-King and his Family’, in his The Danelaw

(London, 1992), pp. 569–604, at 591–7. For the date 966, see Julia Barrow, ‘The Com-

munity of Worcester, 961–c.1100’, in St Oswald of Worcester: Life and Influence, ed.

Nicholas Brooks and Catherine Cubitt (London, 1996), pp. 84–99, at 93–5.