Scragg Donald (Edited). Edgar, King of the English 959-975: New Interpretations (Pubns Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

11

The Frontispiece to the New Minster Charter

and the King’s Two Bodies

CATHERINE E. KARKOV

T

HE New Minster Charter (BL, Cotton Vespasian A.viii) was produced in

Winchester in 966 to commemorate the refoundation of the New Minster

two years earlier by King Edgar with the assistance of his new bishop, Æthel-

wold. The famous frontispiece (frontis. to this book) has been understood largely

as a political statement: a visualization of the ideals of the monastic reform, of

Edgar’s exalted vision of kingship (or Æthelwold’s exalted vision of Edgar’s

kingship), and of the united concerns of king and bishop, specifically as they are

conveyed in the text of the charter the miniature prefaces.

1

The iconography of

the frontispiece has been associated most frequently with that of the Ascension

of Christ,

2

as represented by, for example, the Ascension miniature in the Galba

Psalter of ca. 925–39 (BL, Cotton Galba A.xviii),

3

or the slightly later Benedic-

tional of Æthelwold (BL, Add. 49598),

4

the date of which will be considered

in more detail below. The manuscript’s assimilation to a liturgical book is also

well-remarked, both as regards its lavish format and materials, and as regards

its probable display on the altar of the church.

5

It is written on parchment of a

very high quality and light colour, which is showcased by the ample margins

that surround the text. It is also the only illuminated charter and the only manu-

script written entirely in gold to survive from the Anglo-Saxon period. These

are aspects of the image that have received a great deal of attention from art

historians and historians alike, and ones which I in no way wish to refute. What

I wish to propose in this paper, however, is that the frontispiece may also have

1

C. E. Karkov, The Ruler Portraits of Anglo-Saxon England (Woodbridge, 2004); R.

Gameson, The Role of Art in the Late Anglo-Saxon Church (Oxford, 1995); S. Keynes,

The Liber Vitae of the New Minster and Hyde Abbey, Winchester, British Library, Stowe

944 (Copenhagen, 1996); S. Miller, Charters of the New Minster, Winchester (Oxford,

2001); R. Deshman, The Benedictional of Æthelwold (Princeton, 1995).

2

See ultimately, K. Mildenberger, ‘The Unity of Cynewulf’s Christ in Light of Iconog-

raphy’, Speculum 23 (1948), 431.

3

Illustrated in T. Ohlgren, Anglo-Saxon Textual Illustration (Kalamazoo, MI, 1992),

p. 145.

4

Illustrated in Deshman, Benedictional, pl. 25.

5

See e.g. Gameson, Role of Art, p. 6; Keynes, Liber Vitae, p. 29.

FRONTISPIECE TO THE NEW MINSTER CHARTER 225

had a liturgical meaning, indeed that it may have been as important for its litur-

gical references as it was for its political ones. More specifically, I suggest that

it may have been intended to function as a symbolic evocation of the dedication

of the church, a ceremony traditionally associated with the issuing of foundation

charters on the continent.

6

I am not saying that the image is to be understood

as a record of a specific historical ceremony, though that may well be the case.

There is nothing to rule out such a ceremony having taken place between 964

and 966, especially if the dedication to Mary (and perhaps Peter) was added at

this time.

7

Liturgically, such an addition to the dedication would have required a

rededication ceremony. John of Worcester’s Chronicon records that in 972 Edgar

‘ordered the church of the New Minster, begun by his father King Edmund,

but completed by himself, to be solemnly dedicated’,

8

and it may be that the

rededication ceremony was delayed until that date. What I am suggesting here

is firstly that the image functions not as a record, but as a visual evocation of a

dedication ceremony, created, perhaps with an eye toward the dedication which

eventually took place in 972. As such it furthers the message of purification

and renewal conveyed in the text of the charter itself, serving as a sign of the

reform-era renewal of the church, its eternal purification, and the eternal pres-

ence of Christ within the New Minster, his house on earth. Secondly, I will

suggest that the figure of the king serves a dual function within the miniature,

standing for both Edgar and his royal authority, and for the corporate body of

the New Minster comprised not of its land and architecture but of its community

and congregation.

The

frontispiece

is divided into two unequal levels, the uppermost being

devoted to Christ in Majesty, one hand raised in blessing and the other holding

the book of judgement. He is surrounded by a mandorla supported by four

angels. Below him stands King Edgar flanked by Mary and Peter, the patron

saints of the New Minster. Mary holds a golden palm branch and cross, and

Peter holds his golden cross-key, while Edgar offers the golden charter to Christ

in his outstretched arms. Mary and Peter are also depicted as representatives of

the church rather than members of the kingdom of heaven to whom the church is

being offered. The charter is not being offered to them and they make no gesture

6

Amy G. Remensnyder, Remembering Kings Past: Monastic Foundation Legends in Medi-

eval Southern France (Ithaca and London, 1995), pp. 19–22.

7

Miller, Charters of the New Minster, p. 39, notes that there is no evidence of the dedi-

cation to Mary prior to the reform. Similarly, there is no evidence for the Trinity being

added to the dedication until the 980s. Ch. VIII of the charter states that the re-established

monastery is dedicated to the Saviour, Mary and all the apostles (Rumble, Property and

Piety, p. 82).

8

Keynes, Liber Vitae, p. 29; Miller, Charters of the New Minster, p. xxxi and note 35.

Edmund’s rebuilding is also mentioned in the brief history of the abbey included in the

New Minster Liber Vitae, though it does not reveal which parts of the church or monas-

tery were rebuilt. It is most likely that the dedication commemorated on 10 June in the

calendar of Ælfwine’s Prayerbook (BL, Cotton Titus D.xxvii, fol. 5v) refers to the early

tenth-century dedication as the church is identified only as St Saviour’s with no mention

of Mary, Peter or the Trinity.

226 CATHERINE E. KARKOV

of acceptance,

9

rather they hold out their cross and cross-key in the manner of

offerings and symbols of judgement and salvation.

10

Chapter VIII of the charter

makes it clear that it is to the Saviour, made present in the miniature, that the

grant is made and the charter offered.

11

In addition the palm held by Mary and

the key held by Peter are adventus symbols: the palm of Palm Sunday, the Entry

into Jerusalem, and the entry into paradise; and the key the entry into heaven.

12

It is also possible to understand the two figures as symbols of the larger Church:

Peter as the rock upon which the Church was built, and Mary as Ecclesia. Her

pose with the palm and cross is very like that of the figure of Ecclesia in the

initial to Psalm 51 in the Bury Psalter (Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica, Reg. lat.

12, fol. 62r) from the first half of the eleventh century.

13

It is Edgar’s body that unites the figures on both levels: we read him as si-

multaneously part of the horizontal group of Mary, Edgar, Peter, and as part of

the inverted triangle formed by the bodies of the angels. This latter shape also

serves to create the impression that the angels and Christ are in the process of

descending towards earth, while the king is in the process of ascending towards

heaven. There is, in other words, a mutual coming together. The composition

of the page as a whole certainly suggests a balance between the heavenly and

earthly realms, as well as the oft-noted assimilation of Edgar to Christ as both

king and judge.

14

This is mirrored in the wording, arrangement, and perhaps

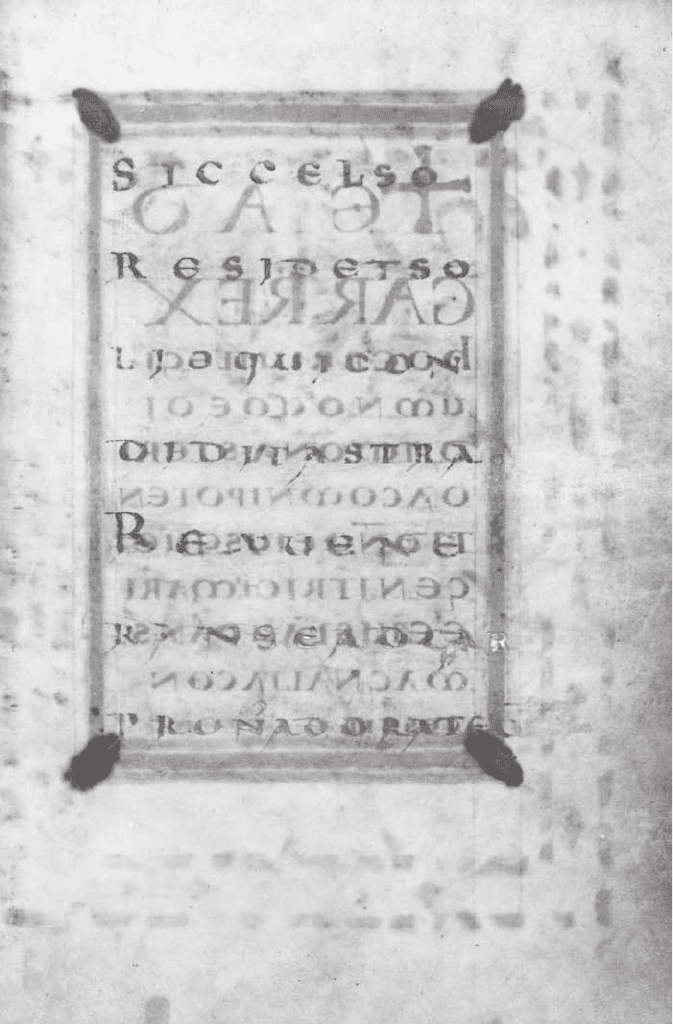

even the metre of the couplet on the facing page (Fig. 11.1):

SIC CELSO RESIDET SOLIO QUI CONDIDIT ASTRA

REX VENERANS EADGAR PRONUS ADORAT EUM

15

But the king’s body is also enlarged. He is bigger than Mary, Peter, and even

Christ, and it is possible to understand his inflated size, along with his pivotal

place in the spatial hierarchy of the page, as an indication that he may stand for

something bigger than just himself.

The pur

ple background of the page and its acanthus border are also symbolic.

9

A point noted by Deshman, Benedictional, p. 87.

10

Karkov, Ruler Portraits, p. 87.

11

The monastery is identified as the ‘Lord’s property’ (possessionem Domini).

12

Deshman, Benedictional, pp. 88, 198–200.

13

Illustrated in Ohlgren, Anglo-Saxon Textual Illustration, p. 265.

14

Deshman, Benedictional, p. 196; Karkov, Ruler Portraits, pp. 86–93.

15

‘Thus he who created the stars sits on a lofty throne; King Edgar, inclined in venera-

tion, adores him.’ Translation based on Rumble, Property and Piety, p. 70. While some

scholars have translated pronus as ‘prostrate’ rather than ‘inclined’, a search of the various

dictionaries has turned up no reason why this should be the case. Rather than wondering

why there is a discrepancy between the upright stance of the king in the portrait, and the

description of him as ‘inclined’, or ‘bowing’, or ‘prostrate’ in the couplet, it might be

useful to think of the the portrait as complementing rather than illustrating the text. On the

one page, Edgar is upright, and the nadir of a V shape formed by the king and the angels

that surrounds Christ; on the other he is humbled beneath the throne of God.

It

is

noteworthy that hexameter is used in the first line of the couplet and pentameter

in the second, perhaps to distinguish the celestial from the earthly realm; see further

M.

Lapidge, ‘Æthelwold as Scholar and Teacher’, yorke, Æthelwold, pp. 89–117, at 96.

FRONTISPIECE TO THE NEW MINSTER CHARTER 227

Fig. 11.1 London, British Library, Cotton Vespasian A.viii, fol. 3r.

© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved.

Disclaimer:

Some images in the printed version of this book

are not available for inclusion in the eBook.

To view the image on this page please refer to

the printed version of this book.

228 CATHERINE E. KARKOV

Traditionally, purple is symbolic of kingship, both earthly and celestial; and of

the blood of Christ eternally present within the church in the form of the wine

of the mass. It had been used by both the Byzantines and Carolingians to figure

royal patronage, the sacrifice of Christ, and the mystery of the transformation of

the Eucharist on the altar,

16

in images with which the Anglo-Saxons were cer-

tainly familiar – such as the manuscripts associated with the courts of Louis the

Pious and Charles the Bald. The purple background of the New Minster fron-

tispiece is an abstract space that contains no architectural specifics such as are

present in, for example, the earlier image of Æthelstan offering his book to St

Cuthbert (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, 183, fol. 1v), or the later image

of Ælfgifu/Emma and Cnut offering their cross to the New Minster (London,

BL, Stowe 944, fol. 6r),

17

or even the image accompanying the blessing for the

dedication of a church on folio 118 verso of the roughly contemporary Benedic-

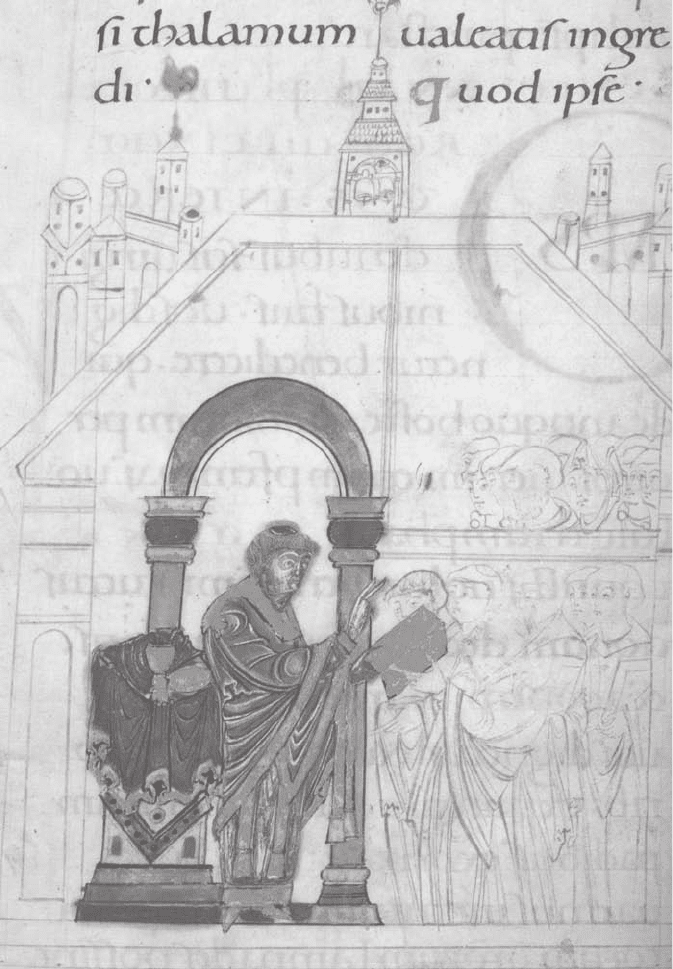

tional of Æthelwold (Fig. 11.2). This abstract, eternal, sacred and royal setting

suggests that the figures have been brought together in the same space, a space

that is at one and the same time both yet neither of this world and the next – a

space of transformation. The acanthus vine that frames that space was a symbol

of the redemption of sin, and was used frequently throughout the Middle Ages

as a device to indicate the joining of heaven and earth.

18

It is just such a transformative setting that was created in the rite of dedica-

tion. During that ceremony the barrier between the secular and the sacred worlds

was broken down and the church was elevated from the secular to the sacred,

removing it from the here and now and placing it within the eternal space of

heaven as domus Dei and establishing the assembled celebrants as a covenant

people of God.

19

This is expressed verbally in the ordo through repeated ref-

erences to the Lord as present in the church during its dedication, and by the

convening of Christ, Mary, the angels and saints as witnesses to the rite.

20

The

foundation legends of a number of continental royal churches and monasteries

go so far as to picture Christ and the angels descending from heaven and per-

forming the dedication or consecration themselves.

21

As far as I know we have

nothing quite so literal surviving from the Anglo-Saxon world, although the Vita

of St Edith of Wilton does describe Christ ‘crowned with glory and honour’,

watching with approval Dunstan’s dedication of the church Edith had built at

Wilton.

22

The ordo as preserved in the Benedictional of Archbishop Robert (Rouen,

Bibliothèque municipale, y.7) is prefaced by a homily of Cesarius of Arles (no.

16

Herbert L. Kessler, Seeing Medieval Art (Peterborough, Ont., 2004), pp. 29 and 33.

17

Illustrated in Karkov, Ruler Portraits, figs. 4 and 17.

18

Kessler, Seeing Medieval Art, p. 75 (citing the apse mosaic at S. Clemente, Rome).

19

See further B. Repsher, The Rite of Church Dedication in the Early Medieval Era (Lew-

iston, Ny, 1998), pp. 6–7.

20

Repsher, Church Dedication, pp. 41, 45–6.

21

Remensnyder, Remembering Kings Past, pp. 80–1.

22

‘The Vita of Edith’, ed. and trans. Michael Wright and Kathleen Loncar, Writing the

Wilton Women: Goscelin’s Legend of Edith and the Liber confortatorius, ed. Stephanie

Hollis, et al. (Turnhout, 2004), p. 53.

FRONTISPIECE TO THE NEW MINSTER CHARTER 229

229) which equates the baptized who constitute the body of Christ with the

dedicated church.

23

In both the Benedictional of Archbishop Robert and the

Egbert Pontifical (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, lat. 10575) the ordo

opens with a prayer uniting the participants with the Lord, and beseeching the

Lord that all their good works begin and end in him:

Actiones nostras quaesumus domine aspirando preueni et adiuuando proseq-

uere ut cuncta nostra operatio a te semper incipiant et per te certa finiantur.

per.

24

The antiphon that follows unites the spaces of heaven and earth in the church

Zache festina descende quia hodie in domo tua oportet me manere. at ille

festinans descendit et suscepit illum gaudens in domo suo. hodie huic domui

salus ad nos facta est. Alleluia

25

The litany, recited during the bishop’s circuit of the church, then summons the

presence of Christ, the angels and saints – Mary and Peter foremost among the

latter.

Kyrieleison

Christe eleison

Christe audi nos

Sancta maria ora

Sancte Michael ora

Sancte Gabriel ora

Sancte Raphael ora

Omnes sancti angeli orate

Sancte Petre ora …

26

This is followed by the bishop knocking on the door of the church and his repeti-

tion of ‘tollite portas principes uestras et eleuamini porte aeternales et introibit

23

‘Omnes enim nos frartes karissimi ante baptismum fana diaboli fuimus . post baptismum

templa christi esse meruimus … Quomodo multa membra christi faciunt corpus unum.’

The Benedictional of Archbishop Robert, ed. H. A. Wilson, HBS 24 (London, 1903), p.

69 (hereafter Robert).

24

‘Deign to direct all our actions towards you, Lord, we beseech you, through your holy

inspiration and carry them on through your assistance so that all of our works may always

begin from you and through you be happily ended.’ Robert, p. 73; Two Anglo-Saxon Pon-

tificals (the Egbert and Sidney Susex Pontificals), ed. H. M. J. Banting, HBS 104 (London,

1989), p. 32 (hereafter Egbert).

25

‘Zacheus, make haste and come down for this day I must abide in thy house. And he made

haste and came down, and received him with joy in his house. This day is salvation come

to this our house. Alleluia’ (Luke 19:5–6, 19:9), Egbert, p. 32; Robert, p. 73.

26

‘Lord have mercy. Christ have mercy. Christ hear us. Holy Mary pray. Holy Michael pray.

Holy Gabriel pray. Holy Raphael pray. All the holy angels pray. Holy Peter pray.’ The

text quoted here is from Egbert. The litany in Robert puts St John before Peter, but then

repeats the name of John after Andrew (Robert, p. 74).

230 CATHERINE E. KARKOV

rex gloriae’,

27

and ‘Quis est iste rex gloriae’.

28

The Benedictional of Robert

includes the prayer ‘Ascendant ad te domine preces nostrae et ab eclesia tua

cunctam repelle nequitiam.’

29

The bishop then enters the church and a second

litany is recited at the altar. The Lord is implored to be present in the church

once again in the prayer ‘Magnificare domine deus noster in sanctis tuis et hoc

in templo aedificationis appare’,

30

and later in the antiphon ‘Ingredere, ben-

dicte domine: preparata est habitatio sedis tue’.

31

As the ceremony progresses

the bishop moves around, into and through the body of the church, tracing, pu-

rifying and blessing each of its parts. The description of similarly traced (though

not purified or blessed) bounds is a normal part of a charter, though not, curi-

ously, of this charter. What this charter provides instead is a presentation of the

community as a chosen people united to both Edgar and Christ through faith

and duty. That they are a people united in Christ and in the king is made clear

in Chapter VIII in which Edgar beseeches the Lord that what Edgar has done for

His (the Lord’s) people, ‘He do for those collected together by Himself under

me’.

32

Elsewhere Edgar refers to his people as his ‘flock’ (‘gregi’).

33

In the dedication ordo the church is also treated consistently as a living being

and equated with its congregation, the chosen people of God.

34

The equation

is present in the earliest commentaries on the rite of dedication, and was well

established in liturgical texts long before the tenth century. Bede, for example,

wrote in his sermon in dedicatione ecclesia:

Domus solummodo in qua ad orandum vel ad mysteria celebranda conven-

imus templum sit domini … appellemur et simus cum manifeste dicat ap-

ostolous: Vos estis templum Dei vivi sicut dicit Deus, in habitabo in eis et

inter illus ambulato. Si ergo templum Dei simus curemus solerter et bonis

satagemus actibus ut in eodem suo templo saepius ipse et venire et missionem

facere dignetur.

35

27

‘Raise up your gates princes and rise eternal gates that the Lord of glory may enter.’

28

‘Who is the king of glory?’

29

Robert, p. 75. ‘We beseech you, O Lord, grant that our prayers may ascend to you and

that your church may be defended against all the assaults of iniquity.’

30

‘Be magnified Lord our God, in your holy ones and appear in this temple built for you’

(Egbert, p. 38; Robert, p. 77).

31

Robert, p. 96. ‘Enter, blessed Lord, the dwelling of your home is prepared.’

32

‘Hoc subnixe efflagitans deposco . ut quod suis egi . hoc agat in mihi ab ipso conlatis

…’

33

Rumble, Property and Piety, p. 80; see also n. 98.

34

Repsher, Church Dedication, pp. 66, 121.

35

Homiliae evangelii, ed. D. Hurst, CCSL 122 (Turnhout, 1955), p. 359; trans. in Repsher,

Church Dedication, p. 30: ‘This house alone in which we gather in order to pray and

celebrate the mysteries is the temple of the Lord … we are called and we are his temple,

since the

Apostle says clearly: you are the temple of the living God, just as God said, I

will dwell in you and I will walk among you. If therefore we are the temple of God, let us

shrewdly take care and busy ourselves with good works so that in this place, his temple,

he himself frequently deigns to come and make his abode.’

FRONTISPIECE TO THE NEW MINSTER CHARTER 231

The equation is at the very heart of the ordo and is reflected in specific passages

far too numerous to document here. It is evoked in the prayer in which the Lord

is magnified in his ‘holy ones’ as his presence within the church is invoked

(‘Magnificare domine deus noster in sanctis tuis …’), and in antiphons and

prayers that request the Lord to bless or bring peace to the church and all who

dwell in it.

36

It is also evoked by the various texts which treat the building, its

furnishings, vessels, vestments, and so on, as if they were people in need of

purification – as for example in the exorcism and blessing of salt, water and

ashes. The result is that the building is effectively baptized as though it were

one of the congregation.

The

phenomenon

has been analyzed at great length by Brian Repsher in his

book on church dedication in the early Middle Ages.

37

Repsher was dealing ex-

clusively with the Romano German Pontifical and the dedication ordo as devel-

oped during the Carolingian reform, but the passage from Bede quoted above,

and the adoption of many of the prayers, blessings and other texts found in the

rites in use on the continent by the compilers of the earliest surviving Anglo-

Saxon pontificals and related manuscripts demonstrates that exactly the same

set of associations was current in Anglo-Saxon England. Admittedly, there is no

Anglo-Saxon pontifical containing the ordo for the dedication of a church that

predates the Benedictine reform. The Dunstan Pontifical (Paris, BN, lat. 943)

is seemingly the earliest, and is tentatively dated after 960 and possibly before

973;

38

it is followed by the Egbert Pontifical, which has been dated variously

between the mid tenth and early eleventh century.

39

Dumville believes that the

Benedictional of Archbishop Robert could not have been written before c. 1020.

He agrees with the view that the manuscript was produced at the New Minster

– it is partially dependent on the Benedictional of Æthelwold – but he points out

36

‘Benedic domine domum istum et omnes habitantes’, Egbert, p. 36; ‘Pax huic domui et

omnibus habitantibus in ea’, Egbert, p. 36 and Robert, p. 76.

37

Repsher, Church Dedication, esp. pp. 33 and 115–20.

38

J. L. Nelson and R. W. Pfaff, ‘Pontificals and Benedictionals’, The Liturgical Books of

Anglo-Saxon England, ed. R. W. Pfaff, OEN Subsidia 23 (Kalamazoo, MI, 1995), pp.

87–98, at 89; N. P. Brooks, The Early History of the Church of Canterbury (Leicester,

1984), p. 248.

39

Banting, the manuscript’s editor, dated it to the mid tenth century on palaeographic

grounds and the evidence of its contents, especially the Cena Domini and coronation

ordos (Egbert, pp. xiv, xxiv–xxv). He also noted that the litany at the beginning of the

dedication ordo includes early English (in addition to Flemish and Northern French) saints

– such as Guthlac, Cuthbert, Omer, Bertin, Vigor, Paternus and Justus (whose head was

given to the Old Minster by King Æthelstan in 924) – but not later English saints such

as Æthelwold, Swithun or Dunstan, as one might expect of a later manuscript. Dumville,

on the other hand, preferred a date of c.

1000 on palaeographic grounds (D. N. Dumville,

Litur

gy and the Ecclesiastical History of Later Anglo-Saxon England (Woodbridge, 1992),

pp. 85–6; D. N. Dumville, ‘On the Dating of Some Late Anglo-Saxon Liturgical Manu-

scripts’, Trans. Cambridge Bibliographical Soc. 10 (1991), 40–58, at 51). Both were un-

certain as to provenance, but Banting tentatively proposed Wessex. Nicholas Orchard has

recently suggested a late tenth- or early eleventh-century date and a ‘southern’ provenance

(The Leofric Missal, HBS 113, 2 vols. (London, 2002), I.262).

232 CATHERINE E. KARKOV

Fig. 11.2 London, British Library, Additional 49598, fol. 118v.

© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved.

Disclaimer:

Some images in the printed version of this book

are not available for inclusion in the eBook.

To view the image on this page please refer to

the printed version of this book.

FRONTISPIECE TO THE NEW MINSTER CHARTER 233

that this does not mean that it was necessarily used at the New Minster.

40

Never-

theless, it does suggest that the dedication ordo as preserved in Robert, and the

closely related Egbert, is not likely to be significantly different from that in use

in Winchester in the late tenth century. (Clearly, churches were dedicated and

consecrated, and it was assumed by the time of the Council of Chelsea in 816

that every bishop had a book containing the consecration ordo.

41

) Moreover, the

blessing for the dedication of a church on folio 118 verso of the Benedictional

of Æthelwold contains the same essential symbolism as that of the ordo. The

date of this manuscript, traditionally 973, has been implicitly, and somewhat

reluctantly, questioned by Michael Lapidge who points out that the manuscript

contains no blessing for the feast of the translation of Swithun, which took place

on 15

July 971.

42

It is odd, to say the least, that an event so important to the

history and development of the Old Minster, Æthelwold’s own church, would

not have been commemorated in his personal Benedictional, and the omission

opens the possibility that the manuscript might be datable to the 960s (or at least

before 971). Whatever its date, the blessing for the dedication of a church with

which the manuscript ends reads:

43

Benedicat et custodiat uos omnipotens deus domumque hanc sui muneris

praesentia illustrare atque suae pietatis oculos super eam die ac nocte dignetur

aperire. Amen.

Concedatque propitius, ut omnes qui ad dedicationem huius basilicae deuote

conuenistis, intercedente beato, illo, et ceteris sanctis suis, quorum reliquiae

hic pio uenerantur amore, uobiscum hinc ueniam peccatorum uestrorum re-

portare ualeatis. Amen.

Quatinus eorum interuentu, ipsi templum sancti spiritus, in quo sancta deus

trinitas iugiter habitare dignetur, efficiamini et, post huius uitae labentis ex-

cursam, ad gaudia aeterna feliciter peruenire mereamini. Amen.

44

40

Dumville, ‘Dating,’ 53.

41

Nelson and Pfaff, ‘Pontificals’, p. 88; Brooks, Canterbury, p. 164. The texts for the conse-

cration and dedicaton of a church are basically the same. Compare the texts for consecra-

tion in Robert to those for dedication in Egbert.

42

M. Lapidge, The Cult of St. Swithun, Winchester Studies 4.ii (Oxford, 2003), p. 23. It does

contain the blessing for the deposition of St Swithun on 2 July. Lapidge suggests that the

texts for the Benedictional may have been assembled before 971, and presumably that the

illustrations were completed afterwards. The Benedictional is dated 973 only because its

royal iconography has been tied to Edgar’s second coronation in that same year (Deshman,

pp. 212–14). There is no reason to assume, however, that the iconography had not been

developed earlier in Edgar’s reign, especially because of the paralleling of Edgar and

Christ, King of Heaven, in the New Minster Charter.

43

The text is ordo XLI in the Romano German Pontifical.

44

‘May the omnipotent God bless and keep you and this house [and] may he deign to

illuminate you and this house by the presence of his gift, and deign to open the eyes of

his kindness over it day and night. Amen.

‘And

may he beneficently grant that all you who devoutly gather at the dedication of

this basilica might be worthy, through the blessed intervention of N. [the saint to whom

the church is dedicated] and those other saints, whose relics here are devoutly venerated

with love, to obtain the forgiveness of your sins. Amen.

‘Since with

their intervention, you yourselves might be made the temple of the Holy