Ripper J. American Stories: Living American History. Volume 2: From 1865

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CONTEMPORARY AMERICA

259

14

Contemporary America

The Life and Times of Al Gore

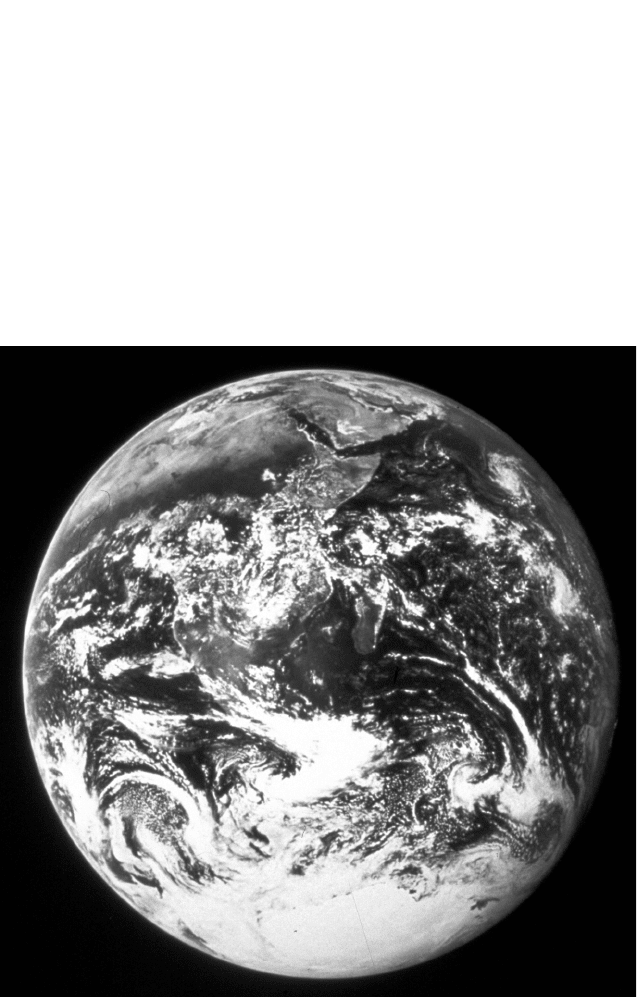

Planet Earth, as seen by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972.

(Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

AMERICAN STORIES

260

You and History

Once a history book moves out of the distant past and into recent and con-

t

emporary scenarios, a new prospect presents itself. The person reading the

book—you—can actually remember the events being described on the page.

You might zoom in a whole lot more when you read about George W. Bush and

the war in Iraq, or about Hillary Clinton’s presidential candidacy, or about how

Congress funds college educations, than when you were reading about Andrew

Jackson and the Bank of the United States. But should the past be considered

history if its major players are still alive? And if so, how best should disco,

rap, Ronald Reagan, crack cocaine, cell phones, abortion, the Internet, Hillary

Clinton, double-tall iced lattes, Harry Potter, the first Gulf War, AIDS, autism,

and the toppling of the Twin Towers be dealt with in a history book designed

for a survey course? This stuff is relevant. But how does it involve you, your

friends, or the guy who sits near you in class listening to his iPod?

Remember that not one single history book is objective. Merely choosing

which topics to include and which to exclude indicates an author’s personal

understanding of historical significance. Choice is bias. Some authors focus

primarily on politics. This book argues that pop culture, race relations, and gender

relations have done at least as much to shape the past and the present as have

politicians and legislators. Furthermore, scholars using the same exact sources

often arrive at conflicting conclusions. Some critics look at Ronald Reagan’s

presidency and see a moral-minded administration that scaled back harmful

federal involvement in the economy. Other critics look at the Reagan years and

see a fear-mongering administration that pandered to immoral business interests.

History is, and can only be, interpretive. Inevitably, historians infuse their books

with their own perspectives. Now that this book dips its pages into the present,

you naturally will have ideas and opinions about the events being described.

You probably know someone who has AIDS or have wondered about your

own risk for infection. You probably care about the cost of Internet access and

the download speeds available. You probably care about whether or not abor-

t

ions are legal or illegal. You probably have heard something about former vice

president Al Gore, the 2000 election, and global climate change, but you may

not know enough to have formed your own opinion. Indeed, understanding

both the past and the present involves much more than basic facts or emotional

reactions. Understanding grows from exposure to new perspectives and from

studying the nuances of an issue.

Al Gor

e and Global Climate Change

In 2006, Al Gore released his documentary An Inconvenient Truth to movie

theaters across the country. He did not anticipate that the movie would draw

261

CONTEMPORARY AMERICA

big crowds or generate much popular interest. After all, he wanted to turn Gen-

eration SUV into environmental healers driving quiet, sensible cars. Earth’s

polar ice caps and glaciers are melting, he pointed out in the film. Carbon in

the form of coal and oil is being dug and pumped out of the ground, burned in

power plants and cars to make energy, and released into the atmosphere where

it is heating up the planet at rates not felt in a millennia. And we should all be

doing something, Gore intoned in the movie’s narration, to reverse the deadly

pollution spewing from our cars’ tailpipes. Not only did Al Gore want to stir

up some eco-crusading, but also he was trying to do it with a documentary,

the American equivalent of trying to get Texans to stop watching football by

asking them to read medical journals written in ancient Greek.

W

ith few exceptions, documentary film directors in the United States can

count on getting about as much attention as poets and playwrights. Only one

man with a nonfiction camera in the United States has made waves in the popu-

lar

mind: Michael Moore. Dressed in casual clothes with his shirt untucked,

and usually sporting a scruffy beard, Moore has played David to corporate

America’s Goliaths. Moore is the populist everyman whose documentaries

champion the proverbial “little guy”: jobless Detroit auto workers in Roger

and Me; peace-loving suburbanites snoozing safely in the mushroom-cloud

shadow of the National Rifle Association in Bowling for Columbine; and duped

voters paying the price for President Bush’s 2003 war in Iraq in Fahrenheit

9/11. By the late 1980s, Moore already had a reputation as a wily common Joe

sticking up for other common Joes. But by the time An Inconvenient Truth hit

theaters, Al Gore had a doubly undeserved reputation as both a boring public

speaker and an out-of-touch liberal. Making Gore’s film even less likely to

thrill crowds was its subject matter: environmental disaster and global climate

change caused by the very same people he hoped would go see the movie,

Americans raised on four and a half hours of mindless television every day.

However, by 2007, in these United States where 5 percent of Earth’s

population uses 25 percent of Earth’s energy, An Inconvenient Truth became

the

third best-selling documentary in history. By 2007, President Bush had

admitted, with six years of reluctance behind him, that humans were indeed

contributing to changing global weather patterns—and this from a president

who had refused in 2001 to sign the international Kyoto treaty that would

have committed the United States to reducing its discharge of carbon dioxide

and other greenhouse gases. And by 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change (IPCC), a worldwide consortium of scientists, had publicly

proclaimed that humans were the leading cause in an impending disaster

capable of making large portions of the globe uninhabitable. In 2007, the

Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded a joint Nobel Peace Prize to Al Gore

and the IPCC for publicizing humanity’s pivotal role in altering the globe’s

AMERICAN STORIES

262

climate. The committee argued that Gore and the IPCC were contributing to

future peace; if climate change is not arrested, one certain consequence is

future chaos, strife, and suffering.

Al Gore, almost single-handedly, made environmental disaster sexy, or at

least scary.

Young Al Gore

Albert (“Al”) Gore Jr. grew up in two places that came, by the late 1970s, to

represent the bases of power in the United States: Washington, DC, and the

Sun Belt (stretching like a superheated Bible train from Georgia to southern

California). With one foot planted in a Tennessee tobacco row and the other

in a Washington hotel where his parents lived most of the year while his

father served in Congress, Al Gore acquired a fine fusion of rural and urban

values. He is a devout Baptist who has studied theology and taken a pro-choice

stance on abortion rights. He loves his family, his country, and the Boston

Red Sox—no offense to southern baseball teams intended. He is a successful

high-tech businessman who has worked in Congress to help small farmers

make a living. Gore graduated from Harvard, served as an army journalist in

the Vietnam War, served as a congressman, a senator, and the vice president

of the United States, lost a presidential election in 2000 under unusual cir-

cumstances,

and emerged as the leading alarm bell for humanity’s role in the

current global climate crisis. As of late 2007, Gore claimed not to be in the

running for president, but he has not ruled out the possibility.

As a boy, Al Gore had access to the privileges of his parents’ money and

connections, but his father, Senator Albert Gore Sr., wanted to make sure

his son would know the value of farm labor and country life. So young Al

spent childhood summers in Carthage, Tennessee, often on sharecroppers’

land plowing hillsides, feeding pigs, tending tobacco shoots, and playing

with children less advantaged than himself. His mother, Pauline, a lawyer

and hard worker herself, thought her husband might have been pushing their

child a bit too hard. She reportedly told her Albert that a boy could grow up

to be president even “if he couldn’t plow with that damned hillside plow.”

1

When not learning to rough it, Al Jr. attended a premier DC–area prep school,

St. Albans, and mingled with political powerhouses at Washington dinner

parties. Visitors and regulars in the halls of Congress would see Al Jr. trail-

i

ng Albert Sr. as the senator walked briskly from meeting to meeting. The

son was expected to keep up.

Albert Gore Sr.’s political career rested on shaky ground. He was a Demo-

c

rat from the South during the years that many middle-of-the-road Democrats

in Dixie headed into the Republican Party. In the late 1950s and early 1960s,

263

CONTEMPORARY AMERICA

some white southerners and Midwesterners were dismayed by policies they

associated with the Democratic Party, especially public school integration and

expansion of welfare programs. Al Gore watched his father struggle to make

sense of a liberal agenda in a state headed in a conservative direction. In 1956,

for example, Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina approached Albert

Sr. on the floor of the Senate and asked him to sign the “Southern Manifesto,”

a pro-segregation declaration that Senator Gore later called “insane.” Thur-

mond

already knew how Gore felt about the manifesto; his intention was to

embarrass Gore in front of their southern colleagues. Gore did not care. He

would stand by his principles. So when Thurmond handed over the manifesto

in front of a room crowded with other southern senators and newsmen and

said, “Albert, would you care to sign our Declaration of Principles?” Gore Sr.

bellowed back, “Hell no.”

2

Albert Sr.’s dedication to liberal values provided

a moral map for his son to follow in his own political career, though Al Gore

Jr. would choose his own issues to champion.

At St. Albans, teachers and friends saw Al Gore as gifted, studious, and

sometimes mischievous. His mother and father had done their utmost to

nurture Gore’s mental acuity. The mischief seems to have arrived on its own:

smoking cigarettes out of sight of school authorities; cutting his church shirt

in the back so he could slip it on and add precious seconds to his morning

sleep; and cutting a friend’s hair while the guy slept.

3

Gore could have gone

to any college he wanted, and he chose Harvard, the incubator of success.

His four years at Harvard coincided with the U.S. escalation of the Vietnam

War, the reality that defined a generation.

Vietnam and the Making of Al Gore

Al Gore entered Harvard in 1965 and graduated in 1969. During those four

years he developed an academic fluency in politics, an interest in journalism,

a passion for environmental policy, and an abiding love affair with his future

wife, Mary Elizabeth “Tipper” Aitcheson, who was attending Boston Uni-

versity

. While some fellow Harvard students protested the war in Vietnam by

seizing an administration building in April 1969 (for which police beat them

in the head with batons), Al Gore had already chosen to express his antiwar

opinions privately or at least sedately, depending on the circumstances. At Gore

Sr.’s invitation, Al Gore had attended the 1968 Democratic National Conven-

tion

in Chicago and watched National Guard troops patrolling the streets in

armored vehicles. Men and women his own age cast their bodies like ballots

in protest against national military policy, and the National Guard and police

responded with tear gas and handcuffs, chaining the sounds of dissent. On

the floor of the convention, Al Gore watched his father give a rousing speech

AMERICAN STORIES

264

(which they had coauthored) publicly opposing U.S. military activities in

Vietnam, an increasingly difficult position for a Tennessee politician to keep

if he also intended to keep his seat in the Senate.

As

1970 approached, bringing with it an election race for Gore Sr.’s sen-

ate

seat, Al Gore, having graduated from college, stood at a crossroads. He

knew he was likely to get drafted to fight in a war he thought was wrong. How

could he best serve his conscience, his country’s call to duty, and his father’s

precarious political position? He disagreed with the U.S. military presence

in Vietnam, yet he thought he was obliged to serve. He and Tipper planned

to marry, and she was only one year away from graduation. With his father’s

connections, Al Gore could have found a way out of active duty service,

probably by landing a spot in the National Guard. Instead, he enlisted in the

army in August 1969.

Al and Tipper got married in 1970 after he finished basic training, and

they moved into a trailer in Alabama. The accommodations were abysmal,

but at least their trailer was better than the first one they checked out, with its

battle-ready platoon of cockroaches roosting inside the refrigerator. Work-

ing

as an army journalist on a two-year enlistment, Gore received orders that

he would be shipping out for Vietnam in the fall of 1970. During the spring

and summer months of waiting, Private Gore wrote small news pieces and

enjoyed his new marriage, but the nation went through the greatest outpour-

ing

of antiwar demonstrations since 1968 and his father lost his reelection

race for the Senate to a conservative Republican named Bill Brock, who ran

nasty campaign ads and received illegal funding from a secret program called

Operation Townhouse—run by aides to President Richard Nixon. The year

1970 was a difficult time for America.

During the late 1960s and on into 1970, the North Vietnamese army had

infiltrated South Vietnam by hiking through neighboring Laos and Cambodia

on a route called the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In 1968, the U.S. Air Force had begun

nonstop bombing runs on the trail, hoping to disrupt the flow of troops and

supplies. The bombs had devastated vast swaths of land in Cambodia and Laos

but had not stopped the North Vietnamese. On April 30, 1970, President Nixon

went on television to tell the nation about an imminent U.S. Army intrusion

into Cambodia. A new wave of domestic protests rolled across America, most

on college campuses. The most poignant tragedy took place on the campus of

Kent State University in Kent, Ohio. Student demonstrations had been going

on for four days, and Ohio’s Governor Jim Rhodes ordered a detachment of the

National Guard to enter the campus at the request of Mayor Leroy Satrom. On

the morning of May 4, 1970, a few hundred students on the campus commons

were protesting the presence of the troops. Many more students were milling

around, simply watching. At 11:45, ninety-six guardsmen stood in formation

265

CONTEMPORARY AMERICA

just as classes got out. Thousands of students spilled onto the commons, most

heading home or to lunch. The soldiers’ commanding officer misinterpreted the

moment and thought the extra students were joining the protest. He ordered

the students to disperse immediately. Over the next half hour, the guardsmen

lobbed tear gas canisters into the crowds of students and marched over the

commons, forcing the students backward. A few students began hurling rocks.

As the confusion intensified, one knot of soldiers knelt in the grass, aimed their

M-15s, and shot sixty-one rounds. The soldiers killed four students—one more

than 200 yards away—and injured nine others. Subsequent investigations,

including one by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), established that

the guardsmen had not been in danger and that more use of tear gas would

have finished dispersing the crowd. Furthermore, the four students who died

had neither been taunting the soldiers nor throwing stones at them.

Just

barely out of college himself, Al Gore, in his GI drab green, could

only watch the news and sympathize. About 5 million university and college

students across the nation spilled onto quads and streets, and by the end of

May 1970, more than 900 universities had closed their doors for the remainder

of the term. President Nixon had not yet done as promised in Vietnam. He

had reduced the army’s presence on the ground to about 225,000 men, but

he had increased the air war and had invaded Cambodia, a nominally neutral

country. More than 100,000 professors joined their students in protest. In

solidarity with the student strikes sweeping through the States, American

GIs in Vietnam refused to fight. Pandemonium reigned in America. Nixon

pulled the troops out of Cambodia, hurried the rate of troop withdrawal from

Vietnam, and emphasized his policy of “Vietnamization,” whereby the South

Vietnamese army itself would be responsible for defending South Vietnam.

Congress nullified the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Student activism worked,

but even as the United States lurched toward withdrawal, Al Gore headed into

Vietnam, where enlisted men were known to “frag” (i.e., toss hand grenades

at) officers who ordered them into worthless reconnaissance missions. Perhaps

as many as one-fourth of the soldiers in Vietnam were smoking marijuana,

and many were using heroin. Gore was heading for dispiriting times.

P

rivate Al Gore served five months in Vietnam as an army journalist, mainly

attached to the Army Corps of Engineers, which was building roads and bridges

near Bien Hoa. Casualty rates remained high in Vietnam throughout 1970 and

1971, but only about 15 percent of military personnel ever served on the front

lines, which were ragged and ill defined in the jungles of Southeast Asia. Gore

seems to have genuinely wanted to be treated the same as any other enlisted

man in the army, but he was an ex-senator’s son, and at least one team of

biographers—David Maraniss and Ellen Nakashima—seem to think Gore’s

immediate superiors did what they could behind his back to keep him safe.

4

AMERICAN STORIES

266

Whatever the exact reasons, Private Gore did not get close to much fighting,

but he did see its consequences: burned-out villages, burned-out spirits of

his fellow GIs, and death. While these tragedies may have strengthened his

opposition to the war, Gore also learned that the situation in Vietnam was

more complex than any anti- or pro-war stance could encompass. Significant

numbers of South Vietnamese people expressed their strong desire to have

the U.S. military remain to protect their freedoms from the encroaching com-

munist

forces. Gore would take this new sense of complexity with him and,

in later years as a congressman, would vote based on the certainty that little

in war or politics was certain.

Al

Gore returned to the United States in 1971, got out of the army, and

moved with Tipper to Nashville, where they both got jobs working for the

Tennessean, a progressive newspaper owned by John Siegenthaler, a former

aide to President John Kennedy. During the four years Gore worked for the

newspaper, the last U.S. troops left Vietnam, and in 1975 the North Vietnamese

army streamed into Saigon, the capital of the South, and declared a com-

munist

victory. Ho Chi Minh was dead, but his cause had triumphed. More

than 58,000 U.S. soldiers had died, more than 300,000 had been wounded,

and the mood in America alternated between somber and disco. Al Gore’s

transformations in the coming years would mirror many of the changes mov-

ing through the nation.

Lear

ning How to Be a Democrat in a Conservative America

From the time of the Tet Offensive in 1968 through the shootings at Kent

State in 1970, citizen distrust of the federal government had escalated. The

Nixon administration’s role in Watergate only worsened the distrust, and

the P

entagon Papers had revealed two decades of intentional lying. Nixon

resigned in 1974 over allegations and revelations about his abuses of power.

By 1978, the public learned about various illegal FBI and Central Intelligence

Agency domestic spying operations, and in turn Congress passed the Foreign

Intelligence Surveillance Act, designed to create congressional and judicial

oversight of the nation’s various spy and police agencies. The FBI’s director,

J. Edgar Hoover, had established COINTELPRO (a counterintelligence pro-

gram)

in the 1950s to spy on and disrupt any domestic political groups that

Hoover saw as threatening to the American political order. Hoover’s number

one target had been Martin Luther King Jr. By the late 1970s, federal govern-

mental

power seemed out of hand, and many people were simply exhausted

from two decades of war and civil rights struggles. By the late 1970s, Al Gore

Jr. was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee. He

was not exhausted by the struggles but rather infused with a calling to steer

267

CONTEMPORARY AMERICA

the nation into a moderate form of liberalism that he thought would be both

acceptable and useful.

R

esponses to the nation’s emotional anxiety and malaise varied. Vast

swarms of 1960s refugees threw their love beads into a box in the closet and

took jobs in education, social service, or the private sector. Disenchantment

with Vietnam combined with adult financial impulses to tame their social

crusading. The hippies’ younger brothers and sisters were entering high school

and college in the mid-1970s. They listened to their siblings’ old Beatles and

Jimi Hendrix albums, but they also bought disco records and disco jackets.

Big boots, big hair, and late-night clubs signaled a shift away from ballot-

box activism and into social revolutions on the dance floor, where black and

white kids could forge a new alliance of fun without the hassle of marching

on Washington. From 1971 through early 1976, Al Gore sampled many of the

same impulses and trends. His hair was long, and his sideburns were thick. He

liked wearing sandals to the office and at least occasionally smoked pot. He

bought all the latest rock albums and wrote articles for the Tennessean about

a five-week-long series of meetings between local evangelicals and members

of a spiritualist commune who had just set up camp near Nashville. Yet he

also investigated local government corruption, studied theology at Vanderbilt

University for a year, worked on a law degree, and talked politics with anyone

who could keep up.

Meanwhile,

as the Gores helped create a liberal enclave of friends, family,

and acquaintances in Nashville, Tennessee, a new coalition of conservative

Christians and fiscal conservatives began to solidify its control over the Re-

publican

Party. That process, beginning in the early 1960s, emanated from a

transformed, suburbanizing South stretching from coast to coast. Conservative

northern Catholics and disgruntled blue-collar workers began joining southern

conservatives in an effort to keep prayer in public schools, reduce welfare allot-

ments,

and stymie the efforts of racial minorities to gain full equality. In fact,

out of disgust with Democrat Lyndon Johnson’s aggressive support for civil

rights and integration, many southern white Democratic voters switched their

allegiance to the Republican Party during the late 1960s. The transformation

helped explain why many conservative Democrats gave their vote to Nixon

in 1968 and why Albert Gore Sr. lost his Senate seat in 1970.

While traditional elected politicians worked crowds at county fairs and

staged rallies, televangelists like Jerry Falwell urged evangelicals to take up

the burden of politics, to throw their combined weight into the ballot box and

tilt the nation’s policies toward their conservative understanding of inerrant

biblical morality. However, during the 1970s, the nation as a whole was not

quite ready to embrace Falwell’s brand of Christian politics. Nixon’s successor,

Gerald Ford, lost a lot of support by pardoning Nixon, so the citizens elected