Richard L. Daft - Management. 9th ed., 2010

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART 5 LEADING510

customers, suppliers, consultants, or other outsiders. Team members use e-mail,

instant messaging, telephone and text messaging, wikis and blogs, videoconferencing,

and other technology tools to collaborate and perform their work, although they might

also sometimes meet face to face. Many virtual teams are cross-functional teams that

emphasize solving customer problems or completing speci c projects. Others are per-

manent self-directed teams.

With virtual teams, team membership may change fairly quickly, depending on

the tasks to be performed.

24

One of the primary advantages of virtual teams is the

ability to rapidly assemble the most appropriate group of people to complete a com-

plex project, solve a particular problem, or exploit a speci c strategic opportunity.

Virtual teams present unique challenges. Exhibit 17.5 lists some critical areas manag-

ers should address when leading virtual teams. Each of these areas is discussed in

more detail below:

25

▪ Using technology to build relationships is crucial for effective virtual teamwork.

Leaders rst select people who have the right mix of technical, interpersonal,

and communication skills to work in a virtual environment, and then make sure

they have opportunities to know one another and establish trusting relationships.

Encouraging online social networking, where people can share photos and per-

sonal biographies, is one key to virtual team success. Leaders also build trust by

making everyone’s roles, responsibilities, and authority clear from the beginning,

by shaping norms of full disclosure and respectful interaction, and by providing

a way for everyone to stay up-to-date. In a study of which technologies make vir-

tual teams successful, researchers found that round-the-clock virtual work spaces,

where team members can access the latest versions of les, keep track of deadlines

and timelines, monitor one another’s progress, and carry on discussions between

formal meetings, got top marks.

26

Today, many virtual teams use wikis to facilitate

this kind of regular collaboration and open information sharing.

▪ Shaping culture through technology involves creating a virtual environment in

which people feel safe to express concerns, admit mistakes, share ideas, acknowl-

edge fears, or ask for help. Leaders reinforce a norm of sharing all forms of knowl-

edge, and they encourage people to express “off-the-wall” ideas and ask for help

when it’s needed. Team leaders set the example by their own behavior. Leaders

also make sure they bring diversity issues into the open and educate members

early on regarding possible cultural differences that could cause communication

problems or misunderstandings in a virtual environment.

▪ Monitoring progress and rewarding members means that leaders stay on top of

the project’s development and make sure everyone knows how the team is pro-

gressing toward meeting goals. Posting targets, measurements, and milestones in

Practice How It’s Done

Use Technology to Build Relationships • Bring attention to and appreciate diverse skills and

opinions

• Use technology to enhance communication and trust

• Ensure timely responses online

• Manage online socialization

Shape Culture Through Technology • Create a psychologically safe virtual culture

• Share members’ special experience/strengths

• Engage members from cultures where they may be

hesitant to share ideas

Monitor Progress and Rewards • Scrutinize electronic communication patterns

• Post targets and scorecards in virtual work space

• Reward people through online ceremonies, recognition

SOURCE: Based on Table 1, Practices of Effective Virtual Team Leaders, in Arvind Malhotra, Ann Majchrzak, and Benson

Rosen, “Leading Virtual Teams,” Academy of Management Perspectives 21, no. 1 (February 2007): 60–69; and Table 2, “Best

Practices” Solutions for Overcoming Barriers to Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Teams, in Benson Rosen, Stacie Furst, and Richard

Blackburn, “Overcoming Barriers to Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Teams,” Organizational Dynamics 36, no. 3 (2007): 259–273.

EXHIBIT 17.5

What Effective Virtual Team

Leaders Do

CHAPTER 17 LEADING TEAMS 511

5

Leading

the virtual workspace can make progress explicit. Leaders also provide regular

feedback, and they reward both individual and team accomplishments through

such avenues as virtual award ceremonies and recognition at virtual meetings.

They are liberal with praise and congratulations, but criticism or reprimands are

handled individually rather than in the virtual presence of the team.

As the use of virtual teams grows, there is growing understanding of what makes

them successful. Some experts suggest that managers solicit volunteers as much as

possible for virtual teams, and interviews with virtual team members and leaders

support the idea that members who truly want to work as a virtual team are more

effective.

27

At Nokia, a signi cant portion of its virtual teams are made up of people

who volunteered for the task.

In a study of 52 virtual teams in 15 leading multinational companies, London Business School

researchers found that Nokia’s teams were among the most effective, even though they were

made up of people working in several different countries, across time zones and cultures.

What makes Nokia’s teams so successful?

Nokia managers are careful to select people who have a collaborative mind-set, and they

form many teams with volunteers who are highly committed to the task or project. The com-

pany also tries to make sure some members of a team have worked together before, providing

a base for trusting relationships. Making the best use of technology is critical. In addition to

a virtual work space that team members can access 24 hours a day, Nokia provides an online

resource where virtual workers are encouraged to post photos and share personal information.

With the inability of members to get to know each another one of the biggest barriers to effec-

tive virtual teamwork, encouraging and supporting social networking has paid off for Nokia.

28

Global Teams

As the example of Nokia shows, virtual teams are also some-

times global teams. Global teams are cross-border work teams

made up of members of different nationalities whose activities

span multiple countries.

29

Some global teams are made up of

members who come from different countries or cultures and

meet face-to-face, but many are virtual global teams whose

members remain in separate locations around the world and

conduct their work electronically.

30

For example, global teams

of software developers at Tandem Services Corporation coor-

dinate their work electronically so that the team is productive

around the clock. Team members in London code a project

and transmit the code each evening to members in the United

States for testing. U.S. team members then forward the code

they’ve tested to Tokyo for debugging. The next morning, the

London team members pick up with the code debugged by

their Tokyo colleagues, and another cycle begins.

31

Global teams present enormous challenges for team lead-

ers, who have to bridge gaps of time, distance, and culture.

32

In some cases, members speak different languages, use differ-

ent technologies, and have different beliefs about authority,

communication, decision making, and time orientation. For

example, in some cultures, such as the United States, commu-

nication is explicit and direct, whereas in many other cultures meaning is embedded in

the way the message is presented. U.S.-based team members are also typically highly

focused on “clock time” and tend to follow rigid schedules, whereas many other cultures

have a more relaxed, cyclical concept of time. These different cultural attitudes can affect

work pacing, team communications, decision making, the perception of deadlines, and

other issues, and provide rich soil for misunderstandings. No wonder when the execu-

tive council of CIO magazine asked global chief information of cers to rank their great-

est challenges, managing virtual global teams ranked as the most pressing issue.

33

Nokia

Innovative Way

© MARK LEONG/REDUX

To update Lotus Symphony, a

package of PC software applications, IBM assigned the project to

teams in Beijing, China; Austin, Texas; Raleigh, North Carolina;

and Boeblingen, Germany. Leading the project, the Beijing group—

shown here with Michael Karasick (center), who runs the Beijing

lab, and lead developer Yue Ma (right)—navigated the global team

through the programming challenges. To help bridge the distance

gap, IBM uses Beehive, a corporate social network similar to Face-

book, where employees create profi les, list their interests, and post

photos.

g

g

g

g

g

glo

b

a

l

team A wor

k

team

m

m

m

m

m

a

d

m

e u

p

o

f

mem

b

ers o

f

d

i

ff

er-

e

e

e

en

nt

en

nt

e

na

na

tio

tio

nal

nal

iti

iti

es

es

who

who

se

se

act

act

ivi

ivi

-

t

t

t

i

ie

t

i

ie

ss

s

s

pan

pan

mu

mu

lti

lti

ple

ple

co

co

unt

unt

rie

rie

s;

s;

m

m

m

m

may

m

m

may

m

op

op

era

era

te

te

as

as

av

a

v

irt

irt

ual

ual

te

te

am

am

o

o

o

o

o

r m

ee

t

f

ace

-

to

-f

a

ce.

PART 5 LEADING512

Organizations using global teams invest the time and resources to adequately

educate employees, such as Accenture, which trains all consultants and most of its

services workers in how to effectively collaborate with international colleagues.

34

Managers working with global teams make sure all team members appreciate and

understand cultural differences, are focused on clear goals, and understand their

roles and responsibilities. For a global team to be effective, all team members must

be willing to deviate somewhat from their own values and norms and establish new

norms for the team.

35

As with virtual teams, carefully selecting team members, build-

ing trust, and sharing information are critical to success.

TEAM CHARACTERISTICS

After deciding the type of team to use, the next issue of concern to managers is design-

ing the team for greatest effectiveness. Team characteristics of particular concern are

size, diversity, and member roles.

Size

More than 30 years ago, psychologist Ivan Steiner examined what happened each

time the size of a team increased, and he proposed that team performance and produc-

tivity peaked at about ve—a quite small number. He found that adding additional

members beyond ve caused a decrease in motivation, an increase in coordination

problems, and a general decline in performance.

36

Since then, numerous studies have

found that smaller teams perform better, although most researchers say it’s impossible

to specify an optimal team size. One recent investigation of team size based on data

from 58 software development teams found that the ve best-performing teams ranged

in size from three to six members.

37

Results of a recent Gallup poll in the United States

show that 82 percent of employees agree that small teams are more productive.

38

Teams need to be large enough to incorporate the diverse skills needed to complete a

task, enable members to express good and bad feelings, and aggressively solve problems.

However, they should also be small enough

to permit members to feel an intimate part of

the team and to communicate effectively and

ef ciently. In general, as a team increases in

size, it becomes harder for each member to

interact with and in uence the others. Sub-

groups often form in larger teams and con-

icts among them can occur. Turnover and

absenteeism are higher because members

feel less like an important part of the team.

39

Large projects can be split into components

and assigned to several smaller teams to

keep the bene ts of small size. At Amazon

.com, CEO Jeff Bezos established a “two-

pizza rule.” If a team gets so large that mem-

bers can’t be fed with two pizzas, it should

be split into smaller teams.

40

Diversity

Because teams require a variety of skills,

knowledge, and experience, it seems likely

that heterogeneous teams would be more

effective than homogeneous ones. In gen-

eral, research supports this idea, showing

that diverse teams produce more innovative

“As demographic shifts sweep our nation and our

community, diversity in public relations is not just a good thing to do, but a neces-

sary business reality,” declares Judy Iannaccone, Rancho Santiago Community

College District communications director. Her professional organization agrees. The

Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) promotes inclusion among work teams

with a diversity tool kit, career Web site, and speakers list. Each year, the Society

recognizes individual chapters for outstanding diversity promotion efforts. The Or-

ange County, California, PRSA diversity committee was one of the 2005 recipients.

Iannaccone, a committee member, is second from the right.

© PRNEWSFOTO/NEWSCOM

CHAPTER 17 LEADING TEAMS 513

5

Leading

solutions to problems.

41

Diversity in terms of functional area and skills, thinking styles,

and personal characteristics is often a source of creativity. In addition, diversity may

contribute to a healthy level of disagreement that leads to better decision making.

Research studies have con rmed that both functional diversity and gender diver-

sity can have a positive impact on work team performance.

42

Racial, national, and

ethnic diversity can also be good for teams, but in the short term these differences

might hinder team interaction and performance. Teams made up of racially and cul-

turally diverse members tend to have more dif culty learning to work well together,

but, with effective leadership, the problems fade over time.

43

As a new manager, remember that team effectiveness depends on selecting the right

type of team for the task, balancing the team’s size and diversity, and ensuring that

both task and social needs are met.

Member Roles

For a team to be successful over the long run, it must be structured so as to both main-

tain its members’ social well-being and accomplish its task. In successful teams, the

requirements for task performance and social satisfaction are met by the emergence

of two types of roles: task specialist and socioemotional.

44

People who play the task specialist role spend time and energy helping the team

reach its goal. They often display the following behaviors:

▪ Initiate ideas. Propose new solutions to team problems.

▪ Give opinions. Offer opinions on task solutions; give candid feedback on others’

suggestions.

▪ Seek information. Ask for task-relevant facts.

▪ Summarize. Relate various ideas to the problem at hand; pull ideas together into

a summary perspective.

▪ Energize. Stimulate the team into action when interest drops.

45

People who adopt a socioemotional role support team members’ emotional needs

and help strengthen the social entity. They display the following behaviors:

▪ Encourage. Are warm and receptive to others’ ideas; praise and encourage others

to draw forth their contributions.

▪ Harmonize. Reconcile group con icts; help disagreeing parties reach agreement.

▪ Reduce tension. Tell jokes or in other ways draw off emotions when group atmo-

sphere is tense.

▪ Follow. Go along with the team; agree to other team members’ ideas.

▪ Compromise. Will shift own opinions to maintain team harmony.

46

Teams with mostly socioemotional roles can be satisfying, but they also can be

unproductive. At the other extreme, a team made up primarily of task specialists will

tend to have a singular concern for task accomplishment. This team will be effective

for a short period of time but will not be satisfying for members over the long run.

Effective teams have people in both task specialist and socioemotional roles. A well-

balanced team will do best over the long term because it will be personally satisfying

for team members as well as permit the accomplishment of team tasks.

TEAM PROCESSES

Now we turn our attention to internal team processes. Team processes pertain to

those dynamics that change over time and can be in uenced by team leaders. In this

section, we discuss stages of development, cohesiveness, and norms. The fourth type

of team process, con ict, will be covered in the next section.

TakeaMoment

t

t

t

ta

ta

tas

k specialist role A ro

l

e

in

n

n

n

n

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

hi

w

ch the individual devotes

p

p

p

p

p

ersonal time and energy to

h

h

h

h

h

elpin

g

the team accomplish

i

i

it

t

t

ts

it

tas

k

.

s

s

s

s

s

ocioemotional role

A

A

r

r

r

ro

ol

r

ro

ol

ei

e

i

nw

n

w

hic

hic

ht

h

t

he

he

ind

ind

ivi

ivi

dua

dua

l

l

p

p

p

p

ro

p

ro

vid

vid

es

es

sup

sup

por

por

tf

t

f

or

or

tea

tea

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

me

m

be

r

s

’

e

m

ot

i

o

n

a

l n

eeds

a

n

d

d

s

s

s

s

so

o

cial unit

y

.

PART 5 LEADING514

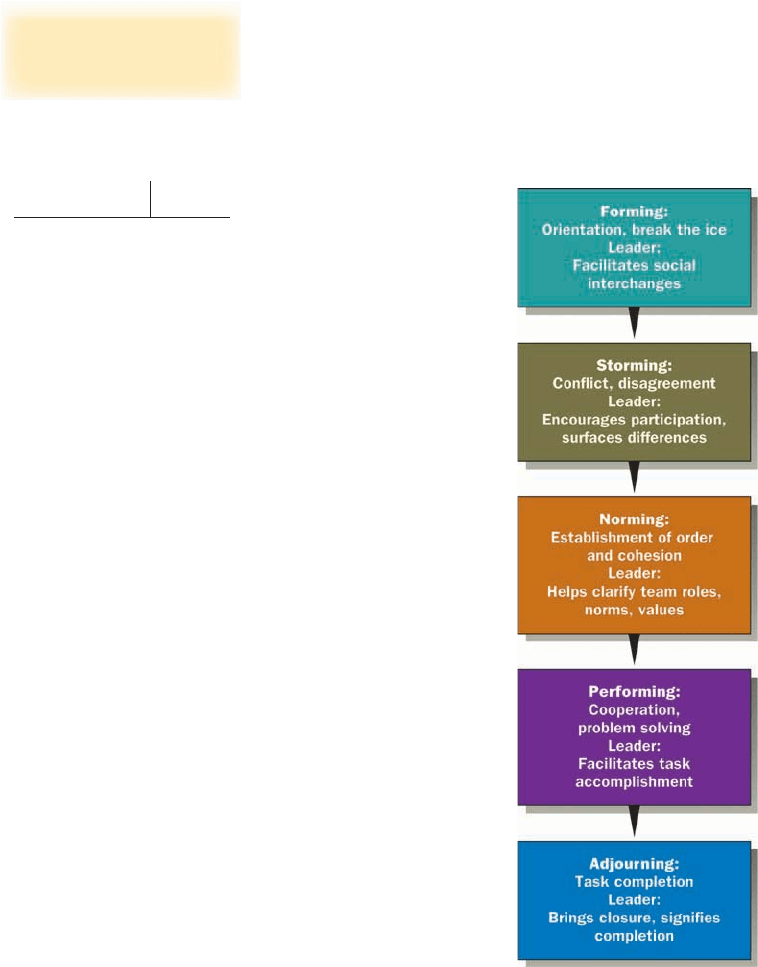

Stages of Team Development

After a team has been created, it develops through distinct stages.

47

New teams are

different from mature teams. Recall a time when you were a member of a new team,

such as a fraternity or sorority pledge class, a committee, or a small team formed to

do a class assignment. Over time the team changed. In the beginning, team members

had to get to know one another, establish roles and norms, divide the labor, and

clarify the team’s task. In this way, each member became part of a smoothly operating

team. The challenge for leaders is to understand the stages of development and take

action that will lead to smooth functioning.

Research ndings suggest that team development is not random but evolves

over de nitive stages. One useful model for describing these stages is shown in

Exhibit 17.6. Each stage confronts team leaders and members with unique problems

and challenges.

48

Forming The forming stage of development is a period of orientation and get-

ting acquainted. Members break the ice and test one another for friendship pos-

sibilities and task orientation. Uncertainty is high during this stage, and members

usually accept whatever power or authority is offered by either formal or infor-

mal leaders. During this initial stage, members are concerned about such things

EXHIBIT 17.6

Five Stages of Team

Development

f

f

f

f

fo

fo

for

min

g

Th

e sta

g

e o

f

team

d

d

d

d

d

d

eve

l

opment c

h

aracterize

d

b

y

o

o

o

or

or

ori

ri

o

entation an

d

ac

q

ua

q

intance

.

CHAPTER 17 LEADING TEAMS 515

5

Leading

as “What is expected of me?” “What behavior is acceptable?” “Will I t in?” Dur-

ing the forming stage, the team leader should provide time for members to get

acquainted with one another and encourage them to engage in informal social

discussions.

Storming During the storming stage, individual personalities emerge. People

become more assertive in clarifying their roles and what is expected of them. This

stage is marked by con ict and disagreement. People may disagree over their percep-

tions of the team’s goals or how to achieve them. Members may jockey for position,

and coalitions or subgroups based on common interests may form. Unless teams can

successfully move beyond this stage, they may get bogged down and never achieve

high performance. During the storming stage, the team leader should encourage par-

ticipation by each team member. Members should propose ideas, disagree with one

another, and work through the uncertainties and con icting perceptions about team

tasks and goals.

Norming During the norming stage, con ict is resolved, and team harmony and

unity emerge. Consensus develops on who has the power, who are the leaders, and

members’ roles. Members come to accept and understand one another. Differences

are resolved, and members develop a sense of team cohesion. During the norming

stage, the team leader should emphasize unity within the team and help to clarify

team norms and values.

Performing During the performing stage, the major emphasis is on problem solv-

ing and accomplishing the assigned task. Members are committed to the team’s mis-

sion. They are coordinated with one another and handle disagreements in a mature

way. They confront and resolve problems in the interest of task accomplishment.

They interact frequently and direct their discussions and in uence toward achiev-

ing team goals. During this stage, the leader should concentrate on managing high

task performance. Both socioemotional and task specialists contribute to the team’s

functioning.

Adjourning The adjourning stage occurs

in committees and teams that have a lim-

ited task to perform and are disbanded

afterward. During this stage, the emphasis

is on wrapping up and gearing down. Task

performance is no longer a top priority.

Members may feel heightened emotional-

ity, strong cohesiveness, and depression or

regret over the team’s disbandment. At this

point, the leader may wish to signify the

team’s disbanding with a ritual or ceremony,

perhaps giving out plaques and awards to

signify closure and completeness.

These ve stages typically occur in

sequence, but in teams that are under time

pressure, they may occur quite rapidly. The

stages may also be accelerated for virtual

teams. For example, at McDevitt Street Bovis,

a large construction management rm, bring-

ing people together for a couple of days of

team building helps teams move rapidly

through the forming and storming stages.

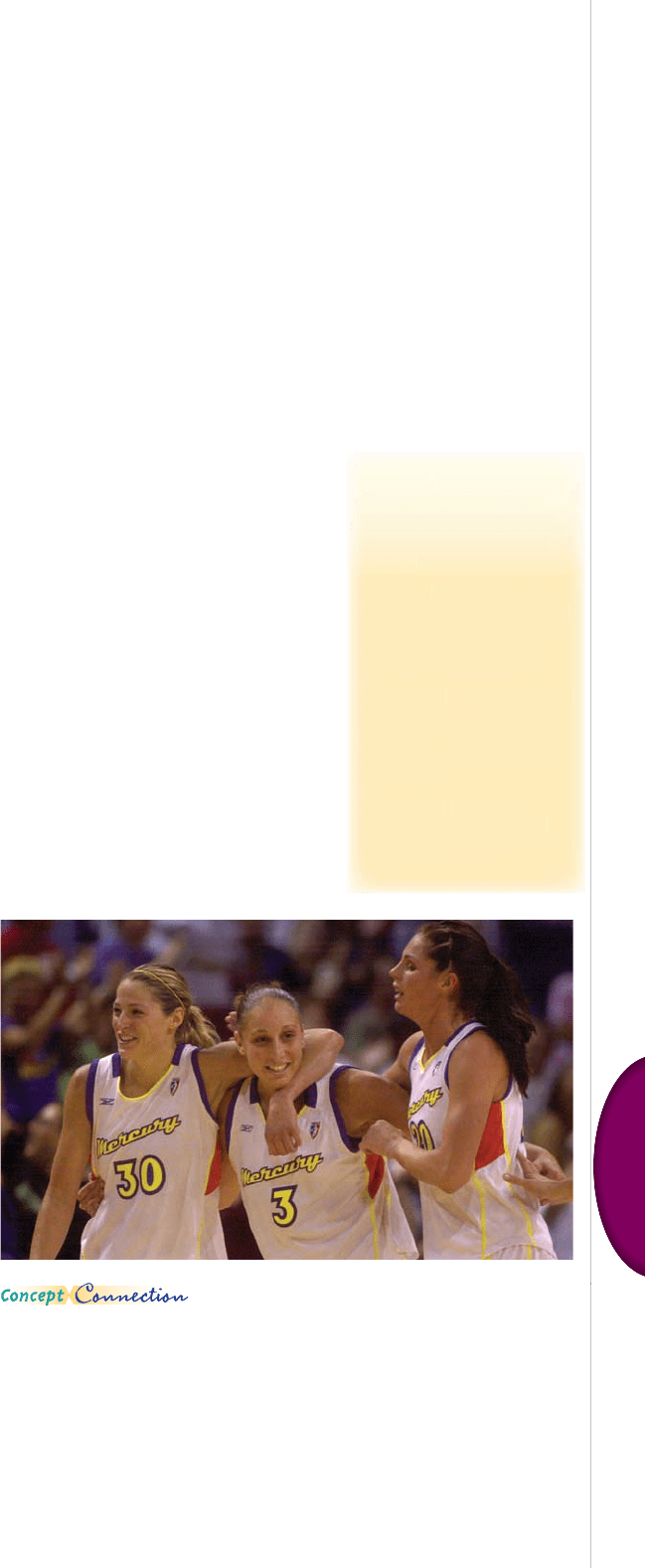

MERCURY PHOENIX WNBA TEAM PHOTO

To accomplish their goals—whether in the business

world or on the basketball court—teams have to successfully advance to the performing

stage of team development. The WNBA’s Phoenix Mercury teammates shown here blend

their talents and energies so effortlessly that they play the game not like separate people

but like a coordinated piece of a whole. Phoenix recently began using psychological

testing as part of the appraisal of new coaches and potential draft picks. Managers

think testing gives them another tool for building a high-performance team. As part-

owner Anne Mariucci puts it, “If a person isn’t dotting the I’s and crossing the T’s, we

know why, and we can surround that person with people who complement that. . . .”

s

s

s

s

s

sto

rm

i

n

g

Th

e stage o

f

team

d

d

d

d

d

d

ev

d

e

l

o

p

ment in w

h

ic

h

in

d

i-

v

v

v

v

vi

id

vi

id

v

ual

ual

pe

pe

rso

rso

nal

nal

iti

iti

es

es

and

and

ro

ro

les

les

e

e

em

me

e

em

me

rge

rge

al

al

ong

ong

wi

wi

th

th

res

res

ult

ult

ing

ing

c

c

c

co

on

c

co

on

c

fli

fl

i

cts

cts

.

n

n

n

n

n

orm

i

n

g

T

h

e stage o

f

team

d

d

d

d

d

d

eve

l

o

p

ment in w

h

ic

h

con

fl

ict

s

s

d

d

d

d

d

d

eveloped during the stormin

g

g

s

s

s

s

st

t

a

g

e are resolved and team

h

h

h

h

h

h

armon

y

and unit

y

emer

g

e.

p

p

p

p

p

er

f

ormin

g

T

h

e stage o

f

tea

m

m

m

m

m

d

d

d

d

d

d

eve

l

o

p

ment in w

h

ic

h

mem

-

b

b

b

b

b

ers focus on problem solvin

g

a

a

a

a

an

n

d accomplishin

g

the team’s

a

a

a

a

as

s

si

g

ned task

.

a

a

a

a

adj

ournin

g

Th

e stage o

f

t

t

t

e

e

e

am

d

eve

l

o

p

ment in w

h

ic

h

m

m

m

m

m

m

embers

p

re

p

are for the team

’

’s

s

s

s

d

d

d

d

d

di

is

d

bandment

.

PART 5 LEADING516

Rather than the typical construction project characterized by confl icts, frantic scheduling,

and poor communications, McDevitt Str

eet Bovis wants its collection of contractors, design-

ers, suppliers, and other partners to function like a true team—putting the success of the

project ahead of their own individual interests.

The team-building process at Bovis is designed to take teams to the performing stage as

quickly as possible by giving everyone an opportunity to get to know one another; explore

the ground rules; and clarify roles, responsibilities, and expectations. The team is fi rst divided

into separate groups that may have competing objectives—such as the clients in one group,

suppliers in another, engineers and architects in a third, and so forth—and asked to come up

with a list of their goals for the project. Although interests sometimes vary widely in purely

accounting terms, common themes almost always emerge. By talking about confl icting goals

and interests, as well as what all the groups share, facilitators help the team gradually come

together around a common purpose and begin to develop shared values that will guide the

project. After jointly writing a mission statement for the team, each party says what it expects

from the others, so that roles and responsibilities can be clarifi ed. The intensive team-building

session helps take members quickly through the forming and storming stages of develop-

ment. “We prevent confl icts from happening,” says facilitator Monica Bennett. Leaders at

McDevitt Street Bovis believe building better teams builds better buildings.

49

Team Cohesiveness

Another important aspect of the team process is cohesiveness. Team cohesiveness is

de ned as the extent to which members are attracted to the team and motivated to

remain in it.

50

Members of highly cohesive teams are committed to team activities,

attend meetings, and are happy when the team succeeds. Members of less cohesive

teams are less concerned about the team’s welfare. High cohesiveness is normally

considered an attractive feature of teams.

Determinants of Team Cohesiveness Several characteristics of team structure

and context in uence cohesiveness. First is team interaction. When team members

have frequent contact, they get to know one another, consider themselves a unit, and

become more committed to the team.

51

Second is the concept of shared goals. If team

members agree on purpose and direction, they will be more cohesive. Third is per-

sonal attraction to the team, meaning that members have similar attitudes and values

and enjoy being together.

Two factors in the team’s context also in uence group cohesiveness. The rst is

the presence of competition. When a team is in moderate competition with other teams,

its cohesiveness increases as it strives to win. Finally, team success and the favorable

evaluation of the team by outsiders add to cohesiveness. When a team succeeds in

its task and others in the organization recognize the success, members feel good, and

their commitment to the team will be high.

Consequences of Team Cohesiveness The outcome of team cohesiveness can

fall into two categories—morale and productivity. As a general rule, morale is higher

in cohesive teams because of increased communication among members, a friendly

team climate, maintenance of membership because of commitment to the team, loy-

alty, and member participation in team decisions and activities. High cohesiveness has

almost uniformly good effects on the satisfaction and morale of team members.

52

With respect to the productivity of the team as a whole, research ndings suggest

that cohesive teams have the potential to be productive, but the degree of productiv-

ity depends on the relationship between management and the working team. One

study surveyed more than 200 work teams and correlated job performance with their

cohesiveness.

53

Highly cohesive teams were more productive when team members

felt management support and less productive when they sensed management hostil-

ity and negativism.

McDevitt Street Bovis

Innovative Way

t

t

t

t

te

tea

m cohesiveness

Th

The

The

e

e

e

e

e

ex

x

tent to which team member

s

s

a

a

a

a

ar

re

attracted to the team an

d

m

m

m

m

m

mot

iv

a

ted

to

r

e

m

a

in in i

t.

CHAPTER 17 LEADING TEAMS 517

5

Leading

As a team leader, build a cohesive team by focusing people on shared goals, giving

team members time to know one another, and do what you can to help people enjoy

being together as a team. Manage key events and make explicit statements to help

the team develop benefi cial and productive norms.

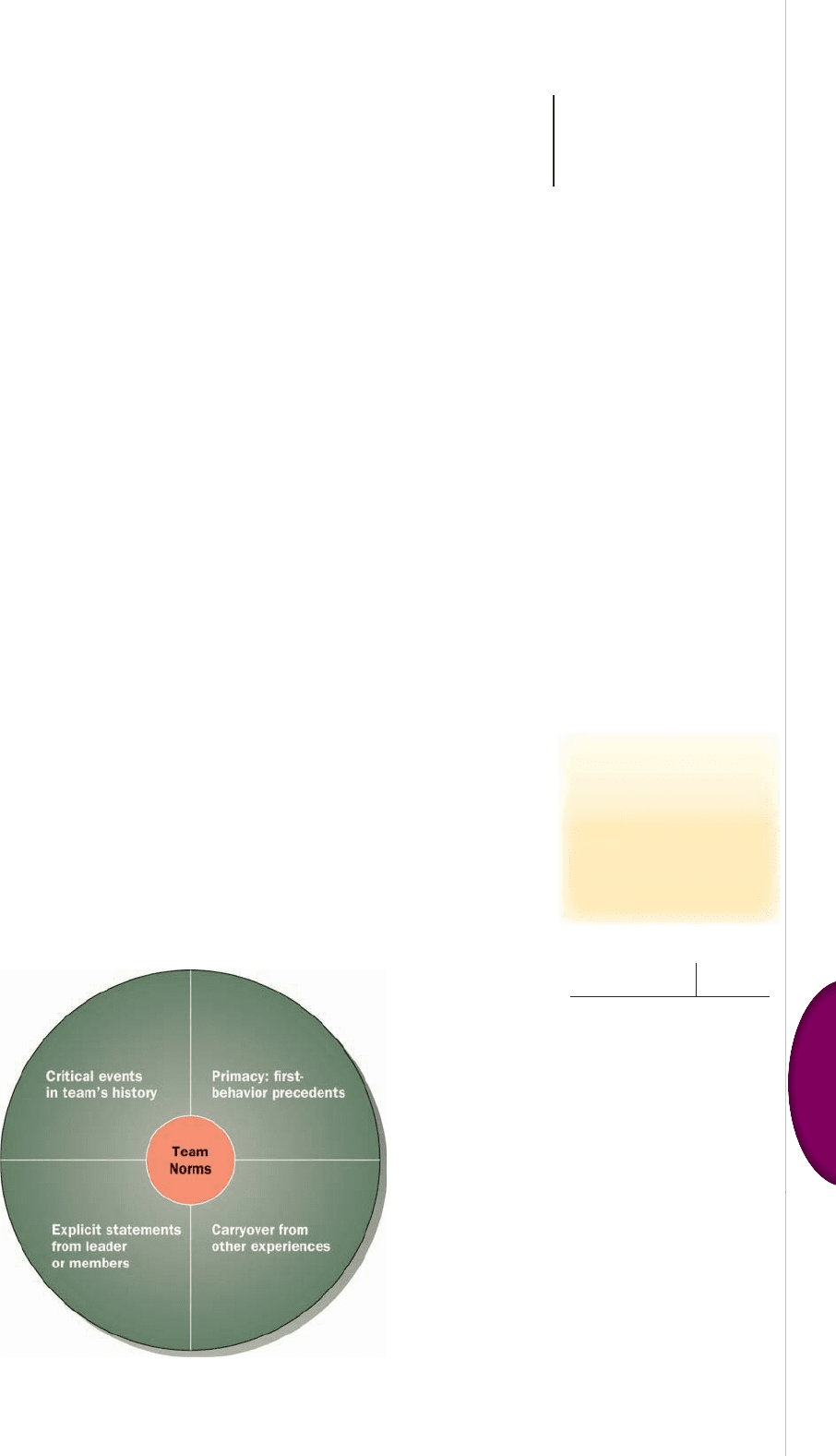

Team Norms

A team norm is an informal standard of conduct that is shared by team members and

guides their behavior.

54

Norms are valuable because they provide a frame of refer-

ence for what is expected and acceptable.

Norms begin to develop in the rst interactions among members of a new team.

55

Exhibit 17.7 illustrates four common ways in which norms develop. Sometimes, the

rst behaviors that occur in a team set a precedent. For example, at one company, a

team leader began his rst meeting by raising an issue and then “leading” team mem-

bers until he got the solution he wanted. The pattern became ingrained so quickly

into an unproductive team norm that members dubbed meetings the “Guess What I

Think” game.

56

Other in uences on team norms include critical events in the team’s

history, as well as behaviors, attitudes, and norms that members bring with them

from outside the team.

Team leaders play an important role in shaping norms that will help the team be

effective. For example, research shows that when leaders have high expectations for

collaborative problem-solving, teams develop strong collaborative norms.

57

Making

explicit statements about the desired team behaviors is a powerful way leaders in u-

ence norms. Explicit statements symbolize what counts and thus have considerable

impact. Ameritech CEO Bill Weiss established a norm of cooperation and mutual

support among his top leadership team by telling them bluntly that if he caught any-

one trying to undermine the others, the guilty party would be red.

58

MANAGING TEAM CONFLICT

The nal characteristic of team process is con ict. Con ict can arise among mem-

bers within a team or between one team and another. Con ict refers to antagonistic

interaction in which one party attempts to block the intentions or goals of another.

59

Competition, which is rivalry among individuals or teams, can have a healthy impact

because it energizes people toward higher performance.

60

TakeaMoment

EXHIBIT 17.7

Four Ways Team Norms

Develop

t

t

t

t

te

tea

m n

o

rm

A

standard of

c

c

c

co

o

nduct that is shared b

y

t

y

eam

m

m

m

m

m

m

em

m

bers and

g

ui

g

des their

b

b

b

b

b

eh

b

b

b

eh

b

avi

avi

or

or.

c

c

c

co

nfl i

ct

A

ntagonistic interac

-

-

t

t

t

i

i

i

on in which one party attempt

s

s

s

t

t

t

o

o

o

thwart the intentions or

g

oa

l

ls

s

s

s

o

o

o

o

o

of

of

f

a

n

o

t

h

e

r

.

PART 5 LEADING518

Whenever people work together in teams, some con ict is inevitable. Bringing

con icts out into the open and effectively resolving them is one of the team leader’s

most challenging, yet most important, jobs. For example, studies of virtual teams

indicate that how they handle internal con icts is critical to their success, yet con-

ict within virtual teams tends to occur more frequently and take longer to resolve

because people are separated by space, time, and cultural differences. Moreover, peo-

ple in virtual teams tend to engage in more inconsiderate behaviors such as name-

calling or insults than do people who work face-to-face.

61

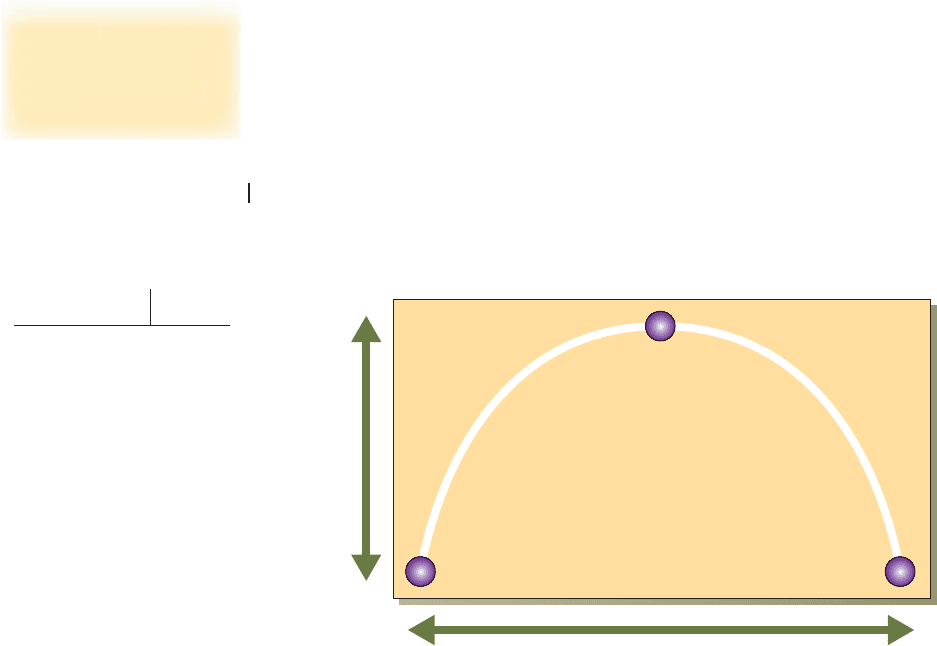

Balancing Confl ict and Cooperation

Mild con ict can actually be bene cial to teams.

62

A healthy level of con ict helps to

prevent groupthink, in which people are so committed to a cohesive team that they

are reluctant to express contrary opinions. Author and scholar Jerry Harvey tells a

story of how members of his extended family in Texas decided to drive 40 miles to

Abilene on a hot day when the car’s air conditioning didn’t work. Everyone was

miserable. Later, each person admitted they hadn’t wanted to go but went along to

please the others. Harvey used the term Abilene paradox to describe this tendency to

go along with others for the sake of avoiding con ict.

63

Similarly, when people in

work teams go along simply for the sake of harmony, problems typically result. Thus,

a degree of con ict leads to better decision making because multiple viewpoints are

expressed. Among top management teams, for example, low levels of con ict have

been found to be associated with poor decision making.

64

However, con ict that is too strong, that is focused on personal rather than work

issues, or that is not managed appropriately can be damaging to the team’s morale

and productivity. Too much con ict can be destructive, tear relationships apart, and

interfere with the healthy exchange of ideas and information.

65

Team leaders have to

nd the right balance between con ict and cooperation, as illustrated in Exhibit 17.8.

Too little con ict can decrease team performance because the team doesn’t bene t

from a mix of opinions and ideas—even disagreements—that might lead to better

solutions or prevent the team from making mistakes. At the other end of the spec-

trum, too much con ict outweighs the team’s cooperative efforts and leads to a

decrease in employee satisfaction and commitment, hurting team performance. A

moderate amount of con ict that is managed appropriately typically results in the

highest levels of team performance.

Go to the ethical dilemma on page 526 that pertains to team cohesiveness and confl ict.

TakeaMoment

High

Low

Low HighModerate

Amount of Conflict

Team Performance

EXHIBIT 17.8

Balancing Confl ict and

Cooperation

g

g

g

g

g

gro

upt

h

in

k

Th

Th

e

t

t

e

d

n

d

ency

f

f

o

r

r

r

p

p

p

p

p

p

eo

pl

e to

b

e so committe

d

to

a

a

a

a

a

cohesive team that they are

r

r

r

r

e

e

l

r

uctant to express contrar

y

o

o

o

op

op

opi

opi

pi

o

n

i

ons

.

CHAPTER 17 LEADING TEAMS 519

5

Leading

Causes of Confl ict

Several factors can lead to con ict:

66

One of the primary causes of con ict is competi-

tion over resources, such as money, information, or supplies. When individuals or

teams must compete for scarce or declining resources, con ict is almost inevitable.

In addition, con ict often occurs simply because people are pursuing differing goals.

Goal differences are natural in organizations. Individual salespeople’s targets may

put them in con ict with one another or with the sales manager. Moreover, the sales

department’s goals might con ict with those of manufacturing, and so forth.

Con ict may also arise from communication breakdowns. Poor communication

can occur in any team, but virtual and global teams are particularly prone to commu-

nication breakdowns. For one thing, the lack of nonverbal cues in virtual interactions

leads to more misunderstandings. In addition, trust issues can be a major source of

con ict in virtual teams if members feel that they are being left out of important com-

munication interactions.

67

Styles to Handle Confl ict

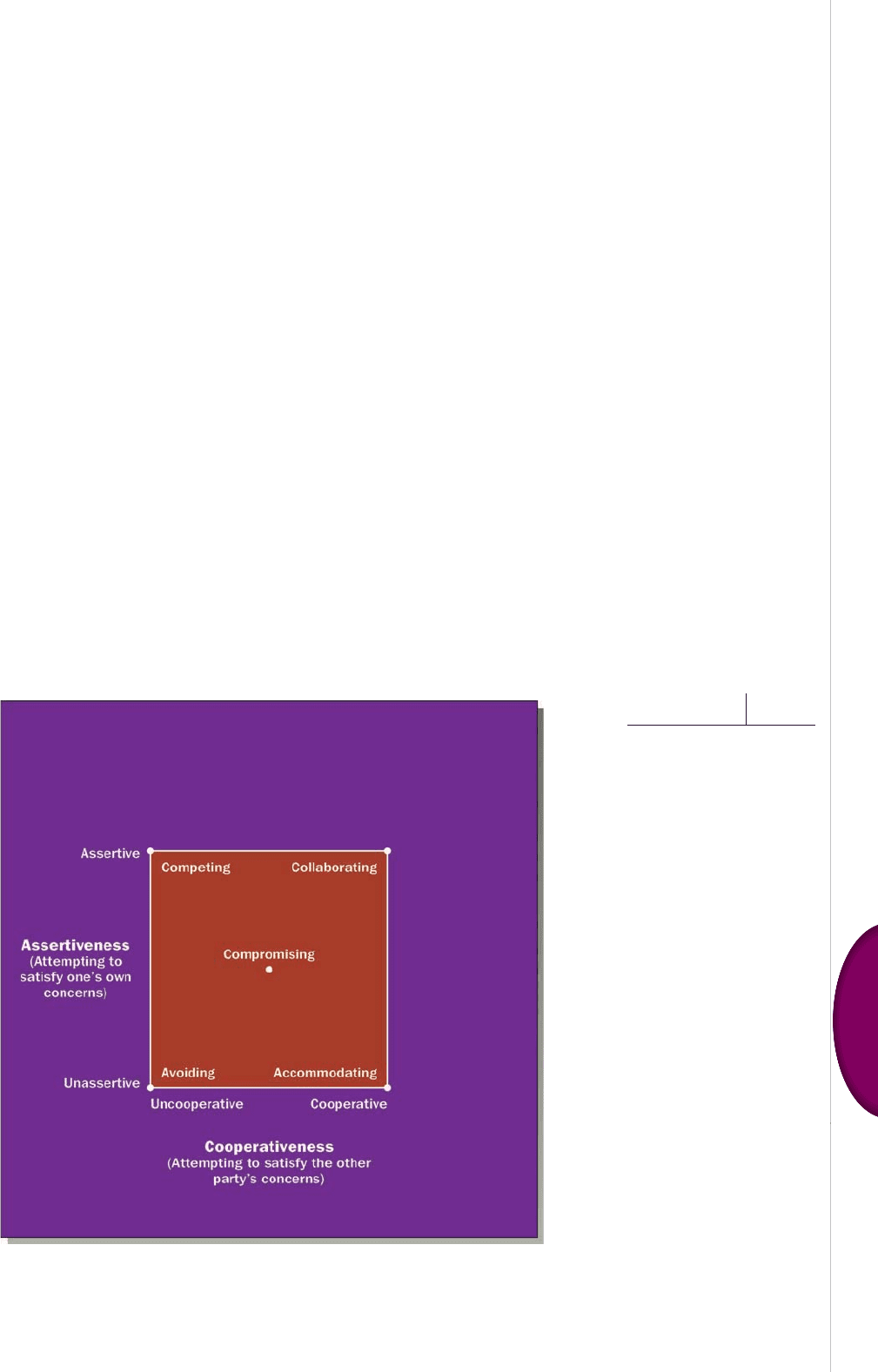

Teams as well as individuals develop speci c styles for dealing with con ict, based

on the desire to satisfy their own concern versus the other party’s concern. A model

that describes ve styles of handling con ict is in Exhibit 17.9. The two major dimen-

sions are the extent to which an individual is assertive versus cooperative in his or

her approach to con ict.

68

1. The competing style re ects assertiveness to get one’s own way and should be

used when quick, decisive action is vital on important issues or unpopular actions,

such as during emergencies or urgent cost cutting.

EXHIBIT 17.9

A Model of Styles to Handle

Confl ict

SOURCE: Adapted from Kenneth Thomas, “Confl ict and Confl ict Management,” in Handbook of Industrial

and Organizational Behavior, ed. M. D. Dunnette (New York: John Wiley, 1976), p. 900.