RAND Corporation. Social Science for Counterterrorism

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Representing Social-Science Knowledge Analytically 425

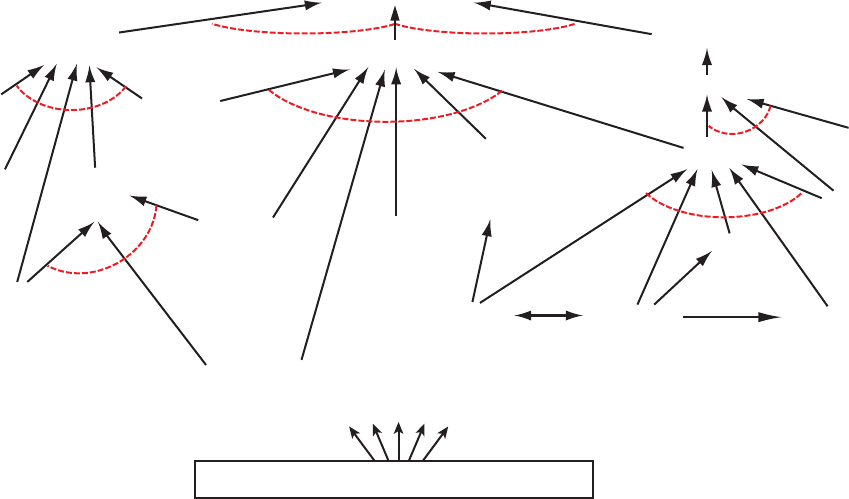

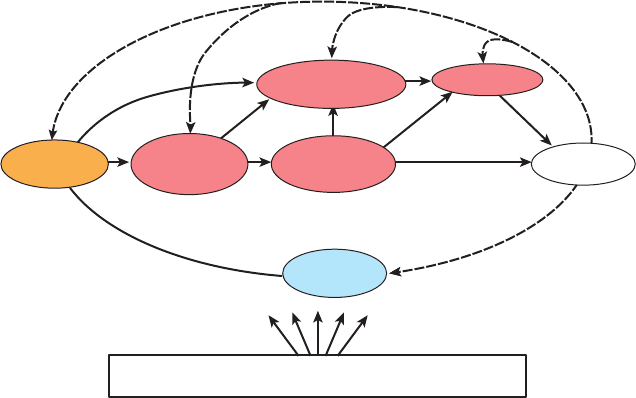

Figure 11.10

Factor Tree for Root Causes

RAND MG849-11.10

Low government capacity (e.g., few institutions, no rule of law);

population movements, demographic shifts

Increased root-cause

likelihood of terrorism

and

ors

ors

ors

ors

ors

and

Facilitative norms

about use of violence

Mobilizing structuresPerceived grievances

(hatred, humiliation, desire for revenge)

Cultural

propensity

for

violence

Source of recruits

Foreign

occupation or

dispossession

Ideology

(e.g., religion)

Social

instability

Alienation

Perceived

illegitimacy

of regime

Cultural

imperialism

Population

growth

and increasing

number of

youth

Social and

family

Political discontent

t 'FXQPMJUJDBM

opportunities

t $POTUSBJOFEDJWJM

liberties

t &MJUFEJTFOGSBO-

chisement and

competitions

Human insecurity

t -BDLPGFEVDBUJPO

t -BDLPGIFBMUIDBSF

t $SJNF

Technological

change and

modernization

t 6SCBOJ[BUJPO

t $MBTTTUSVHHMF

t 8FBMUIJOFRVBMJUZ

t 1PQVMBUJPOEFOTJUZ

t %JTMPDBUJPOT

&DPOPNJDQSPCMFNT

t 6OFNQMPZNFOU

t 1PWFSUZ

t 4UBHOBUJPO

t *OBEFRVBUFSFTPVSDFT

Repression

Globalization Loss of identity

426 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

level factors are determined by a myriad of complex and subtle factors

indicated lower in the tree.

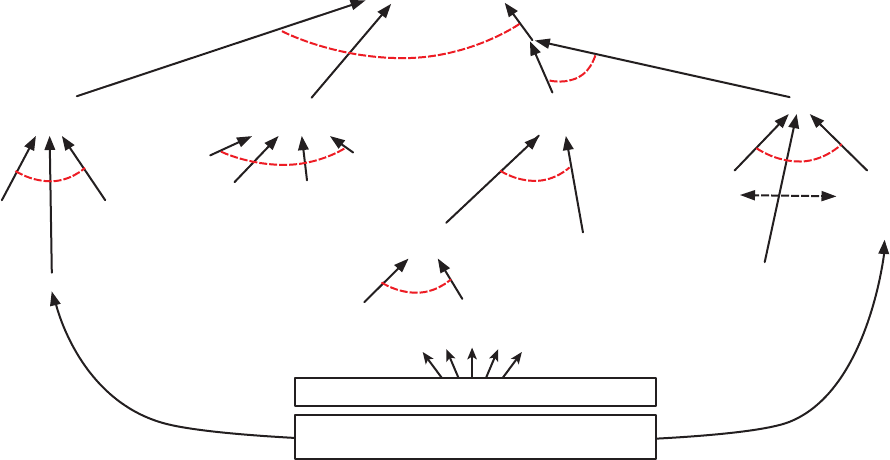

In comparing this with Helmus’s tree (Figure 11.11) on individual-

level radicalization, we see considerable overlap despite the differences

in the perspectives. Helmus sees radicalizing groups as necessary but

also perceived rewards in one form or another (not included in Noricks’s

discussion of root causes), grievances, and a desire for change. Once

again, the richness of discussion depends on factors farther down the

tree, but we are interested in the high-level abstractions.

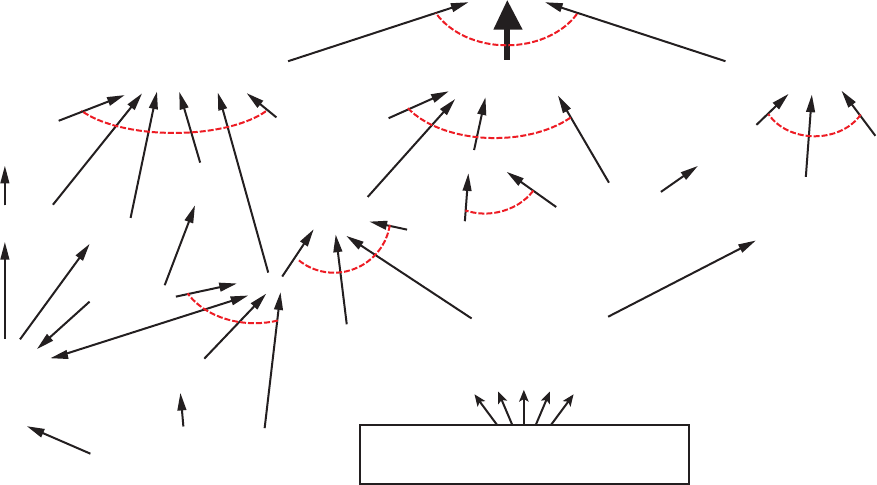

Paul’s tree (Figure 11.12) relates to public support. Despite having

begun by thinking about the group level of analysis, Paul found himself

recasting issues in terms of individuals’ propensity to support terrorism—

but with individuals affected by social pressures and incentives. His

factor tree again has much in common with the earlier ones. How-

ever, he puts more emphasis on “identity” and social pressures. He also

highlights the “negative” kind of social pressure caused by intimida-

tion. If the terrorist organization is able to credibly threaten a popula-

tion or individuals within it, then that will increase social pressures to

support the terrorist activity—perhaps only in a passive manner, per-

haps by providing materiel support, or perhaps by becoming a terrorist

(more the subject of Helmus’s paper). Paul also includes future-benefit

considerations (which, implicitly could be negative, reducing public

support). Individuals trade off “benefits” and “costs,” but how they do

so varies a great deal. ey may value such intangibles as prestige; they

may merely be swept along in a fervor. e result may be less rational-

analytic than emotional behavior.

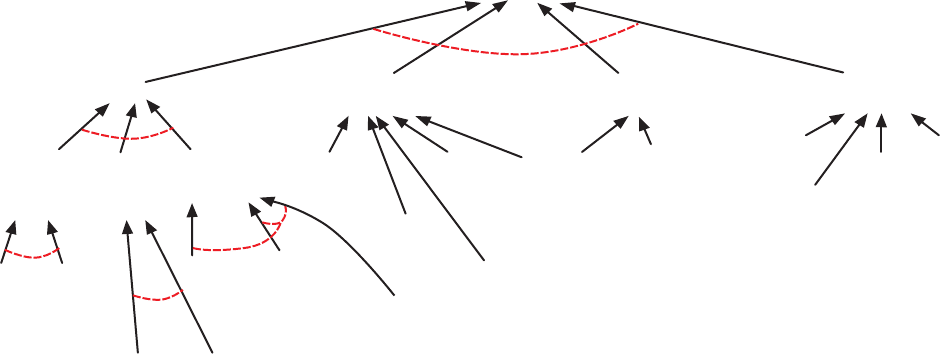

Figure 11.13 is my adaptation from Jackson (2009), which exam-

ines how terrorist organizations decide whether to take particular

actions. I have translated that into a factor tree analogous to the ones

above. Here, again, we see factors for benefits and risks but also refer-

ence to costs and risks; we also see the importance of resources and

information. Is the potential action going to provide benefits in terms

of advancing group interests or strategy? If so, is it presumably consis-

tent with interests and ideology and also (an “and” condition) in align-

ment with constraints of external influences, such as the interests of

state sponsors, cooperating groups, or supportive social movements?

Representing Social-Science Knowledge Analytically 427

Figure 11.11

Radicalization Factor Tree

Individual willingness

to engage in terrorism

Radicalizing

social groups

Real and perceived

rewards

Felt need to respond to

grievances

Passion for change

Collective grievance

and duty to defend

Personal grievance

and desire for revenge

t

t

Personal attacks on

self or loved ones

Effects of post-traumatic

stress disorder

...

Religious

change

tCaliphate

t.JMMFOJBMJTN

Political change

tIndependence

of state

tAnarchy...

Single-issue

change

tEnvironment

tAbortion

tAnimal rights...

Alienation

Recruitment

Bottom-up

peer groups

tPrisons

t3BEJDBMGBNJMJFT

t3FMJHJPVTTFUUJOHT

advocating violence

t*OUFSOFUTJUFT

ands

ors

or

ors

Financial

Excitement

Social

Religious

or ideological

ors

Sense of identity

tied to collective

Attack

on collective

and

SOURCE: Adapted from Helmus (2009).

or

RAND MG849-11.11

Social, economic, and political discrimination;

other broad contextual factors

Charismatic, entrepreneurial leadership

428 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

Figure 11.12

Public Support Tree

RAND MG849-11.12

Propensity to support terrorism

Cultural

obligations

Kinship,

fictive kinship,

other ties

Group provision

of social

services

Regime

illegitimacy

Occupation

Group

intimacy

Ideology and

social-movement

considerations

Desire

to defend

Grievances

Desire for

revenge

Shared goals

Intimidation

Future benefit

t1SFTUJHF

t#BOEXBHPOJOH

t%JTDPVOUQBSBNFUFS

Unacceptable

group behavior

t&YDFTTJWFDJWJMJBODBTVBMUJFT

t*NQPTJUJPOPGSFMJHJPVTSVMFTy

Felt need for resistance or

BDUJPOCZQSPYZGPSQVCMJDHPPE

*EFOUJmDBUJPOXJUI

terrorist group

Social pressures and

incentives

and

and

Misperceptions

or self-deception

favoring group

Humiliation,

frustration,

alienation,

hatred

Charged negative

emotions

Normative

acceptability

of violence

Lack of opportunity for

QPMJUJDBMFYQSFTTJPOBOE

freedom, repression

ors

ors

ors

or

ors

ors

Charismatic, entrepreneurial leadership;

group propaganda

4063$&"EBQUFEGSPN1BVM

Representing Social-Science Knowledge Analytically 429

Figure 11.13

Decisionmaking

SOURCE: Adapted and simplified from Jackson (2009).

RAND MG849-11.13

Propensity to act

Perceived benefits

Acceptability of

perceived risks

Acceptability of

resources required

Sufficiency of

information

Positive

relevant-

population

reaction

Advance

of group

interests

or strategy

Positive

reactions

within group

Legiti-

macy

Pressures

to act

tCompetitional

t&WFOUESJWFO

and?

ands

ors

Consistency

with interests

and ideology

Alignment

with external

influences

tState sponsors

t$PPQFSBUJOHHSPVQT

t.PWFNFOUTBOE

networks...

Legitimacy

Need of

group to act

tFor cohesion

t#JBTUPBDUJPO

Action-specific

preferences

and?

Permissiveness

of group criteria

Weakness

of defenses

Effectiveness vs. counter-

terrormsm measures

Group

capability

Group

risk

tolerance

Resources

available

t.POFZ

tTechnology

t1FPQMF

tT ime

Situational

awareness

Technical

knowledge

Communi-

ications

Threshold

needs

or

and?

430 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

Claude Berrebi’s paper (Berrebi, 2009), written from an econo-

mist’s perspective, also emphasizes the rational-choice model and its

explanatory power. As one would expect in an economist’s discussion,

it considers benefits, costs, and risks.

Considering the observed overlap, it is natural to consider whether

a high-level synthesis exists for these various “views of the elephant.”

Such a synthesis is not straightforward because the appropriate abstrac-

tion depends on what insights one is looking to highlight or which

of several stories one wants to tell. I will merely illustrate one synthe-

sis. e story is expressed in terms of influence on individuals and

groups.

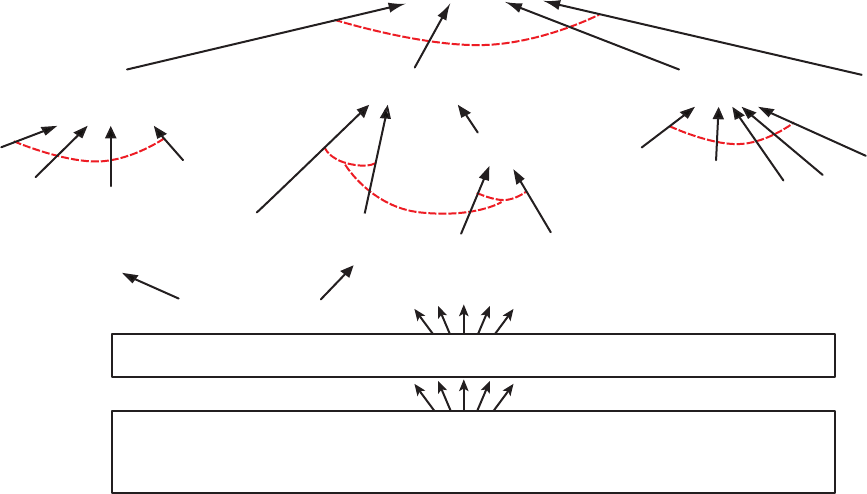

For this, it is useful to begin with a system-level influence diagram

(Figure 11.14, adapted from Gvineria [2009] and Davis [2006]). In this

diagram, the terrorist organization already exists, but its operational

capabilities (central oval) may increase or decrease as a function of the

resources and organizational structures available to it, which in turn

depend on support obtained from states (for example, Iranian support

Figure 11.14

A System Diagram Relating to Terrorism

Target

vulnerabilities

Attacks’

effectiveness

Context, developments, motivations, ideologies, perceptions,...

Counterterrorism efforts

±

±

RAND MG849-11.14

Support for

terrorism

Organizations

and resources

for terrorism

operational

capabilities

At-time “demand”

for attacks; decisions

Terrorist attacks

Terrorist

Representing Social-Science Knowledge Analytically 431

for Hizballah), general populations (for example, broad popular senti-

ment support for al-Qaeda), or more specific popular support (sup-

port of expatriate communities in western Europe for al-Qaeda or local

affiliates).

24

Given a degree of operational capability, the terrorist organization

has the potential to conduct attacks, but the potential effects depend

also on the targets’ vulnerabilities. If support for action is strong enough,

and if operational capability is adequate, then attacks will ensue. ose

will have effects, which in turn will affect subsequent support. Another

spectacular event akin to the attacks on the U.S. World Trade Center

and the Pentagon might increase support for what would be seen as a

revitalized al-Qaeda. Or it might spark back-reaction because of the loss

of human life and retaliation. Or both. e consequences, then, might

have positive or negative feedback effects (hence the ± symbology).

e primary function of Figure 11.14 is to illustrate how sup-

port for terrorism matters. Support, however, comes in many differ-

ent forms. Suppose that we put aside state support, which is a subject

unto itself, and consider only public support. at also varies markedly.

Support may be so great that individuals will actually become terror-

ists (see Helmus’s discussion); or it may come in the form of active or

passive public support without direct participation in terrorism attacks

(see Paul’s discussion). Such public support is widely regarded in social

science as a key to the success or decline of terrorism (see the classic,

Galula [1963], for example; and discussions in Paul [2009], Gvineria

[2009], and Stout, Huckabey, and Schindler [2008, p. 52], which is

based on perspectives from within al-Qaeda).

On reflection and on comparing the discussions, it seems that the

high-level factors contributing to either radicalization or active public

support are very similar, although sometimes with different names

depending on the author.

is suggests a composite view as shown in Figure 11.15, which

shows the propensity for participating in terrorism or public support

of the terrorist effort (an aggregation for simplicity) to be a function of

four primary factors:

432 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

Figure 11.15

A High-Level Factor Tree Relating to a Population’s Support for Terrorism

RAND MG849-11.15

Attractiveness of

and identification with

cause or activity

Strength of

ideology

(e.g., religion)

or cause

Group,

glory

Perceived

regime

illegitimacy,

dissatisfaction,

anger...

Religious,

ideological,

and ethical

basis

Threat to homeland

or people

Cultural

propensity

for violence

Personal

grievances

Perceived legitimacy

of terrorism

Acceptability of

costs and risks

Personal

risks and

opportunity

costs

Counter-

vailing

social

pressures

Societal

costs

Necessity,

effectiveness

Absence of

alternatives

History of

success

ands

ors

and

ors

or

or

–

Charismatic, entrepreneurial leadership

Active support-raising efforts by terrorist organizations and counterterrorist efforts by states and others

Other factors of environment and context:

t International political and political-military factors (including state support of terrorism, occupations, ...)

t Economic issues, social instability, human insecurity (within context of demographics, globalization, ...)

t Cultural issues (within contexts of globalization, modernization, ...)

t History and cultural history, ...

Propensity to participate in or

actively support terrorism

Radicalizing,

mobilizing

groups

–

–

Intimi-

dation

Emo-

tional

factors

±

Representing Social-Science Knowledge Analytically 433

attractiveness of and identification with a cause or other action•

perceived legitimacy of terrorism•

acceptability of costs and risks•

presence of radicalizing or mobilizing groups.•

e first of these is my renaming in “positive terms” the factor related

to motivation. As has been repeatedly noted by terrorism scholars (for

example, Sageman, 2008; Jenkins, 2006), terrorists do not see them-

selves as “terrorists.” ey often see themselves as warrior heroes sup-

porting either a cause (religious or otherwise) or, at least, an activity

that they find exciting. e second factor uses the term “legitimacy.”

As we know from accounts of terrorists’ internal debates, such mat-

ters are important—even if they conveniently discover rationale for

doing what they are motivated to do anyway (Sageman, 2008; Stout,

Huckabey, and Schindler, 2008, pp. 232 ff.). e third factor, accept-

ability of costs and risks, is implicit in some of the companion papers

and explicit in others (for example, Jackson’s, as well as Berrebi’s). e

fourth factor appears explicitly in Noricks’s and Helmus’s work and

implicitly in the others. Note also, at the bottom, that charismatic,

entrepreneurial leaders can be very important (Gupta, 2008).

At the second and third levels of detail, Figure 11.15 shows more

than a dozen constituent factors. All of these are discussed in one form

or another in the papers by Noricks, Helmus, Paul, Jackson, and Ber-

rebi. e papers offer different perspectives as to how they come into

play, but the differences are arguably not of first-order importance.

As discussed above, “ands” and “ors” are important in Figure

11.15. To first order, the research base suggests that all of the top-level

factors must surpass some threshold or terrorism will decline. However,

there are different ways that a cause may be seen as attractive and that

terrorism can be seen to be legitimate. Similarly, there are a number

of factors affecting the “negatives,” that is, determining the percep-

tion of costs and risks. Although only one of several possible high-

434 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

level perspectives,* the figure highlights overarching factors that appear

repeatedly in the research literature in one form or another. Further, it

does so holistically rather than asserting, for example, that participa-

tion in or support of terrorism is just a consequence of a cost-benefit

calculation or that the current wave of terrorism is supported by popu-

lar sympathy driven only by Salifism or only by political grievances. To

put matters otherwise, the intent of the diagram is to cover all of the

available respectable explanations, not just the one deemed currently

by some particular experts to be dominant in a particular time and

place.

At first glance, it may appear that the factors of Figure 11.15 are

assumed to combine via rational choice: Is there value to the terrorism,

is it legitimate, are the costs and risks acceptable, and is there a mecha-

nism? at might, in the instance of some individuals and groups, be

correct and, as discussed in a companion paper (Berrebi, 2009), much

can be understood with the rational-choice model. Social science tells

us, however, that that model is often not descriptive. Even if we con-

sider an individual or group contemplating terrorism, so that the con-

cept of “decision” is perhaps apt, the more general concept is arguably

limited rationality. People attempt to be rational, that is, to take actions

consistent with their objectives, but they are affected by many influ-

ences, which include

†

the constraints of • bounded rationality, which include erroneous

perceptions, inadequate information, and the inability to make

the complex calculations under uncertainty demanded by strict

“rational choice”; the result is often heuristic decisionmaking,

which employs simplified reasoning and may even accept the first

solution that appears satisfactory

*

For example, if one wises to emphasize the differences between root-cause factors and fac-

tors affecting public support or causing the decline of terrorism (see Cragin, 2009), then the

“super aggregation” represented by Figure 11.16 is inappropriate.

†

See the Nobel Prize lectures Simon (1978) and Kahneman (2002) for discussions of

bounded rationality and cognitive biases. Davis, Kulick, and Egner (2005) review modern

decision science with extensive citations to the rational-analytic and “naturalistic” decision-

making literatures.