Pugnaire F.I. Valladares F. Functional Plant Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

cases, oxygen appears to leak out of submerged roots and oxidize toxic substances and

nutrients in the rhizosphere and oxygenate marsh sediments (Howes et al. 1981, Armstrong

et al. 1992). Castellanos et al. (1994) reported that Spartina maritima aerates surface sedi-

ments in wetlands of southern Spain, creating conditions favorable for the invasion of

Arthrocnemum perenne. In eastern salt marshes in North America, Hacker and Bertness

(1996) found that the aerenchymous Juncus maritimus increased the redox potential in its

rhizosphere, which corresponded with increased growth of I. frutescens, a woody-stemmed

perennial, and the extension of Iva’s distribution to lower elevations in the marsh.

Plantago coronopus and Samolus valerandi are clumped with tussocks of the aerench-

ymous J. maritimus in dune slacks on the coast of Holland, where survival rates appeared to

be enhanced by soil oxygenation and oxidation of iron, manganese, and sulfide (Schat and

Van Beckhoven 1991). When P. coronopus and Centaurium littorale were grown with

J. maritimus in the greenhouse, growth and nutrient uptake were improved (Schat 1984).

Substrate oxygenation and facilitation may also occur in freshwater marshes. In green-

house experiments, undrained pots containing Typha latifolia (cattail) had dissolved oxygen

contents over four times greater than those without Typha, and other marsh plants grown

with Typha survived longer and grew larger than those in pots without Typha when pot

substrates were kept between 118C and 128C (Callaway and King 1996). In the field, Myosotis

laxa (herbaceous perennials) growing next to transplanted Typha were larger and produced

more fruits that those isolated from Typha.

PROTECTION FROM HERBIVORES

Positive interactions may be indirectly mediated through herbivores. Themeda triandra,an

East African savanna grass, is preferred by many herbivores, and suffers 80% mortality

from grazers when not associated with less-palatable grass species (McNaughton 1978). As

codominance with unpalatable species increases, mortality of Themeda rapidly decreases.

Similar examples of associational defenses have been reported by others (Attsat and

O’Dowd 1976).

In the Sonoran Desert, paloverde seedlings are protected by various shrub species

(McAuliffe 1986). Ninety-two percent of naturally occurring C. microphyllum in the open

was eaten by herbivores; but only 14% of the seedlings that were touching shrubs were

consumed. McAuliffe (1984a) also found that young Mammillaria microcarpa and Echinocer-

eus englemannii cacti were much more common under live and dead Opuntia fulgida where

spine-covered stem joints from the nurse plant protected them from herbivores.

In south-east Spain, unpalatable Artemisia barrelieri shrubs facilitate seed germination

and seedling establishment of more palatable Anthyllis cytisoides shrubs in addition to

providing shelter from herbivory during early stages of growth, and before competitive

displacement by Artemisia (Haase et al. 1997).

In northern Sweden, Betula pubescens experiences high herbivory when associated with

plants of higher palatability, Sorbus aucuparia or Populus tremuloides, but low herbivory

when associated with plants of lower palatability, Alnus incana (Hjalten et al. 1993). Hay

(1986) found that several species of highly palatable seaweeds were protected from grazers in

safe microsites provided by unpalatable seaweed species.

As noted earlier, the positive effect of coastal scrub shrubs on Q. douglasii seedling

recruitment (Callaway 1992) was caused in part by shade from the shrub canopies; however,

analysis of the mortality of individual seedlings showed that the causes and the timing of

mortality differed significantly under shrubs and in the open grassland. Predation on acorns

appeared to be due to rodents and was much higher under shrubs than in the grassland only

1 m away. Emergent shoots, however, were eaten by deer and experienced much higher

predation in the grassland than under shrubs. Consequently, blue oak acorns that survived

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 440 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

440 Functional Plant Ecology

early rodent predation under shrubs became seedlings that occupied sites relatively free from

deer predation on shoots. Similarly, seed and seedling predation appears to be a major

factor limiting Pinus ponderosa to shrub-free, hydrothermally altered soils in the Great

Basin (Callaway et al. 1996).

In most cases referred to earlier, benefactor species appear to physically shelter or hide

beneficiary species from herbivores (see Chapter 15). A similar phenomenon, called associ-

ational resistance by Root (1972) and associational plant refuges by Pfister and Hay (1988),

may occur when some species experience less herbivory as a function of the visual or olfactory

complexity of the surrounding vegetation. A number of ecologists have found that commu-

nity complexity serves as an impediment to search efficiency, in contrast to physical protec-

tion from herbivores or close association with unpalatable species (Root 1972, Risch 1981).

POLLINATION

Plants that are highly attractive to pollinators may facilitate their less-attractive neighbors by

enticing insects into the vicinity. Thomson (1978) found that Hieracium florentinum received

more visits from pollinators when it was mixed with Hieracium auranticum than when alone.

Moeller (2004) found that populations occurring with multiple congeners had higher pollin-

ator availability and lower pollen limitation than those occurring alone. Similarly, Ghazoul

(2006) found that pollinator visits to Raphanus raphanistrum, a self-incompatible herbaceous

plant, increased when it occurred with one or a combination of Cirsium arvense, Hypericum

perforatum, and Solidago canadensis than when it occurred alone. In the understory of

deciduous forests in Ontario, Laverty and Plowright (1988) recorded higher fruit and seed

set in Podophyllum peltatum (mayapples) that were associated with Pedicularis canadensis

(lousewort) than those that were not near Pedicularis plants. In later studies, Laverty (1992)

found that higher fruit and seed set in mayapple, which produces no nectar, depends on

infrequent visits from queen bumble bees that accidentally encounter mayapple while collect-

ing nectar from Pedicularis, the magnet species.

Johnson et al. (2003) experimentally evaluated the potential for species that do not attract

large numbers of pollinators to benefit from neighbors using the nonrewarding bumblebee-

pollinated orchid, Anacamptis morio, and associated nectar-producing plants in Sweden.

Pollen receipt and pollen removal for A. morio was significantly greater for individuals

translocated to patches of nectar-producing plants (Geum rivale and Allium choenoprasum)

than for those placed outside (>20 m away) patches. Their results provide strong support

for the existence of facilitative magnet species effects. Geer et al. (1995) have shown that three

co-occurring species of Astragalus facilitate each other’s visitation rate of pollinators rather

than competing for them.

There may be even facilitation to attract pollinators between a rust fungus (Puccinia

monoica) and Anemone patens (Ranunculaceae). The presence of rust’s pseudoflowers may

increase visitation rate to Anemone, though the positive effect could be counterbalanced

because sticky pseudoflowers remove pollen from visiting insects and fungal spermatia

deposited on flower stigmas reduce seed set (Roy 1996).

MYCORRHIZAE AND ROOT GRAFTS

Woody plants may form intraspecific and interspecific root grafts in which resources and

photosynthate move among individuals (Bormann and Graham 1959, Graham 1959,

Bormann 1962). Bark girdling of one Pinus strobus sapling grafted to a conspecific neighbor

resulted in a significant drop in the diameter growth of the ungirdled member (Bormann

1966). He reported that the intact tree supported root growth in the girdled tree for a period

of 3 years. Bark-girdling of nongrafted white pines resulted in death within a year, but grafted

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 441 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

Facilitation in Plant Communities 441

trees remained alive for 2 or more years after girdling. Bormann argued that the development

of naturally occurring white pine stands is shaped by both competition and ‘‘a noncompeti-

tive force governed by inter-tree food translocation.’’ However, because both independently

acquired and shared resources would require intact transport tissues, it is not clear how

grafting overcame the effect of girdling.

Mycorrhizal fungi also facilitate the exchange of carbon and nutrients (Chiarello et al. 1982,

Francis and Read 1984, Walter et al. 1996). Grime et al. (1987) found that labeled

14

CO

2

was

transferred from Festuca ovina to many other plant species in artificial microcosms that shared

a common mycorrhizal network, but not to others that did not share the network. The presence

of mycorrhizae led to decreased biomass of the dominant species, F. ovina, and increased

biomass of otherwise competitively inferior species, including Centaurea nigra, and ultimately

experimental microcosms that were infected with mycorrhizae were more diverse than those

that were not infected. Marler et al. (1999) studied the role of mycorrhizae on interactions

between Festuca idahoensis and Centaurea maculosa, a major invasive weed in North America.

They found that mycorrhizae mediated strong positive effects of Festuca on Centaurea. There

were no direct effects of the mycorrhizae on the growth of either species, but when Centaurea

was grown with large Festuca in the presence of mycorrhizae, they were 66% larger than in the

absence of mycorrhizae. The fact that mycorrhizae mediated much stronger growth responses

from large Festuca than small Festuca suggests that mycorrhizae mediated parasite-like inter-

actions, such as those that occur between myco-heterotrophic parasites (Leake 1993).

Mycorrhizal networks connecting roots of neighboring plants transfer nutrients from one

plant to another, in such a way that may counterbalance the negative effects of competition,

as in P. strobus on seedlings recruiting underneath them (Booth 2004). However, beneficial

influence of trees acting as a source of ectomycorrhizal infections to seedlings depend on the

distance to the tree, because growth is maximized at intermediate distances from the trunk

(Dickie et al. 2005).

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN FACILITATION AND INTERFERENCE

In the central Rocky Mountains of the USA, Ellison and Houston (1958) showed that

herbaceous species in the understory of P. tremuloides (quaking aspen) were stunted unless

the tree roots were excluded. However, after trenching, the growth of understory species

exceeded that of the surrounding open areas. Facilitative mechanisms of shade or nutrient

inputs appeared to have the potential to facilitate understory species, but their effects were

outweighed by root interference. More recently, a large number of studies have demonstrated

that positive and negative interactions operate at the same time. Walker and Chapin (1986)

demonstrated that A. tenuifolia litter had the potential to facilitate S. alaxensis and

P. balsamifera in greenhouse experiments and in the field (see earlier). However, under

natural conditions, S. alaxensis, P. balsamifera, and Picea glauca grew poorer in A. tenuifolia

stands than in other vegetation. In other experiments, they found that root interference and

shading in alder stands was more influential on the other species than nutrient addition via

litter, and overrode the effects of facilitation. In a similar study in Glacier Bay, Chapin et al.

(1994) found the reverse: that early to mid-successional species, such as A. sinuata, affected

the late-successional P. sitchensis in positive ways (nutrient uptake and growth) and in

negative ways (germination and survivorship). P. sitchensis seedlings that were planted

in A. sinuata stands accumulated over twice the biomass and acquired significantly higher

leaf concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus than seedlings planted in P. sitchensis forests.

However, as found at the other site, root trenching in A. sinuata stands further increased

growth and nutrient acquisition, demonstrating that competitive and facilitative mechanisms

were operating simultaneously. In contrast to the interior floodplain, however, the facilitative

effects of Alnus on its neighbors overrode root interference in natural conditions.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 442 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

442 Functional Plant Ecology

In the Patagonian steppe, Aguiar et al. (1992) found that various shrub species protected

grasses from wind and desiccation, but strong facilitative effects were only expressed when

root competition was experimentally reduced. In the same system, Aguiar and Sala (1994)

found that young shrubs had stronger facilitative effects on grasses, but the positive effects

declined as grass densities increased near the shrubs.

During primary succession on volcanic substrates, Morris and Wood (1989) measured

both negative and positive effects of Lupinus lepidus, the earliest colonist, on species that

arrived later the successional process, but concluded that the net effect of Lupinus was

facilitative. On the island of Hawaii, the exotic tree Myrica faya is a successful invader on

volcanic soils where it is replacing the native tree, Metrosideros polymorpha (Whiteaker and

Gardener 1985). Walker and Vitousek (1991) found that direct effects of the invading Myrica

on the native Metrosideros were both facilitative and interfering. Myrica enriched the nitro-

gen content of soils and improved Metrosideros growth in greenhouse experiments, and shade

from Myrica improved Metrosideros seedling germination and survival. However, Metrosi-

deros germination was sharply decreased by litter from Myrica, and the growth of young

Metrosideros did not improve in the shade of Myrica in the field. They concluded that the lack

of regeneration of Metrosideros under the canopies of Myrica in the field was the result of

these negative mechanisms dominating the positive mechanisms.

Q. douglasii deposits large amounts of nutrients to the soil beneath their canopies and soil,

and litter bioassays demonstrate strong facilitative effects of these components on the growth

of a dominant understory grass, B. diandrus (Callaway et al. 1991). In the field, however, the

expression of this facilitative mechanism is determined by the root architecture of individual

trees. Q. douglasii with low fine root biomass in the upper soil horizons and those that

appeared to have roots that reached the water table (much higher predawn water potentials)

elicited strong positive effects on understory biomass. In contrast, trees with high fine root

biomass in the upper soil horizons and those that did not appear to root at the water table

(much lower water potentials) elicited strong negative effects on understory productivity. In

field experiments, they demonstrated that soil from beneath Q. douglasii, regardless of root

architecture, had strong positive effects; but that root exclosures only improved understory

growth under trees with dense shallow roots. Thus in this ecosystem, as in the Alaskan

floodplain studied by Walker and Chapin (1986), root interference, when present, outweighed

the positive effects of nutrient addition.

Palatable intertidal seaweed species that depend on less-palatable species for protection

(Hay 1986, see earlier) are poor competitors with their benefactors. Hay found that, in the

absence of herbivores, several highly palatable seaweed species grew 14%–19% less when in

mixtures with their benefactors than when alone. In the presence of herbivores, however,

palatable species survived only when mixed with competitively superior, but unpalatable

species. In this system, the effects of competition with neighbors were outweighed by the

protection they provided.

The balance of facilitation and interference may change with the lifestages of the interacting

plants. Patterns of nurse plant mortality observed in numerous systems indicate that species

may begin their lives as the beneficiaries of nurse plants and later become significant competi-

tors with their former benefactors as they mature. McAuliffe (1988) found that young Larrea

tridentata plants were positively associated with dead Ambrosia dumosa, a species critical to the

initial establishment of Larrea. Similarly, mature saguaros were associated disproportionally

with dead paloverde trees that commonly function as nurse plants to seedling saguaros

(McAuliffe 1984b). However, in both of these cases, young Larrea may do better in the

shade of Ambrosia that are already dead because the positive effects come without any

competitive cost. In the Tehuacan Valley of Mexico, N. tetetzo that is nursed by M. luisana

(Valiente-Banuet et al. 1991) eventually suppresses the growth and reproduction of its bene-

factor (Flores-Martinez et al. 1994). The same occurs with Opuntia rastrera (Silvertown and

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 443 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

Facilitation in Plant Communities 443

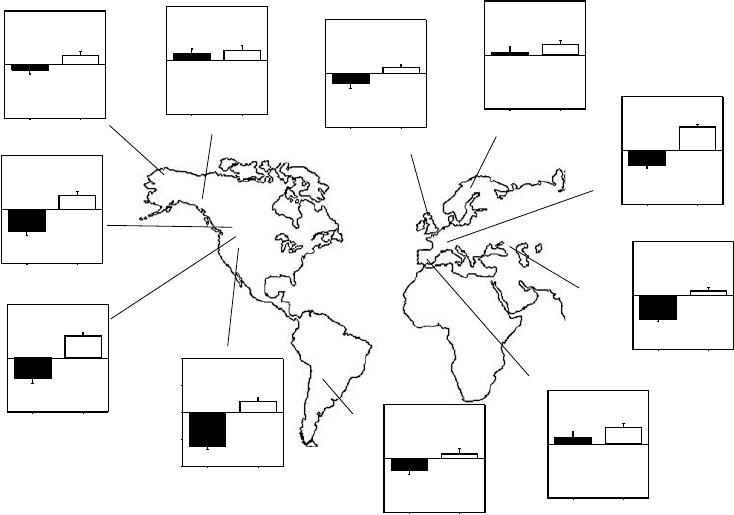

Wilson 1994). Archer et al. (1988) found that Prosopis glandulosa trees provide a focal point

for the regeneration of many other species in southcentral Texas (Figure 14.2), but Prosopis

regenerated very poorly in these clusters once they were established. In dry systems in south

east Spain, Armas and Pugnaire (2005) found that the short-term balance of the inter-

action between Cistus clusii shrubs and Stipa tenacissima grasses shifted easily in response to

environmental variability and had important consequences for the structure of the plant

community.

Other studies have shown that a particular benefactor species may have facilitative

effects on some species, but competitive effects on other similar species. A. tridentata

dominates large regions of the Great Basin of Nevada, USA, but is completely absent

from outcrops of phosphorus-poor hydrothermally altered andesite where P. ponderosa is

abundant (DeLucia et al. 1988, 1989). Field experiments demonstrated that A. tridentata

outcompetes P. ponderosa for water off of the altered andesite refuges, and prevents

P. ponderosa from expanding onto typical soils of the Great Basin. Another pine species,

Pinus monophylla, is often common in mixtures with A. tridentata, but found only as seedlings

on altered andesite (Callaway et al. 1996). Experiments indicated that P. monophylla is not

prevented from maturing on altered andesite by soil conditions, but by the absence of

A. tridentata that acts as a nurse plant for P. monophylla (DeLucia et al. 1989, Callaway

et al. 1996). Both species of pines have similar leaf-level physiological characteristics and

nutrient requirements.

In the upper zones of southern California salt marshes, the perennial subshrub Arthroc-

nemum subterminale exists in a matrix of winter ephemeral species that emerge when soil

salinity drops at the beginning of the rainy season. Arthrocnemum has strong facilitative

effects on some codominant ephemerals and they tend to occur in its understory (Callaway

1994). Another, othewise similar annual is competitively reduced by Arthrocnemum and is

more common in the open between the shrubs.

Bertness and Callaway (1994) hypothesized that the balance between facilitation and

interference is affected by the harshness of physical conditions, and that the importance of

facilitation in plant communities increases with increasing abiotic stress or increasing con-

sumer pressure. Alternatively, they hypothesized that the importance of competition in

Prosopis

Xanthozylum

Celtis

Condalia

Diospyros

Zizyphus

Schaefferia

Opuntia

1

2

3

6

7

Time

1 m 3 m 6 m 16 m

Height, m

FIGURE 14.2 Illustration of the development of shrub clusters facilitated by Prosopis glandulosa in

Texas grasslands. (Redrawn from Archer, S., Scifres, C., Bassham, C.R., and Maggio, R., Ecol.

Monogr., 58, 111, 1988. With permission.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 444 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

444 Functional Plant Ecology

communities would increase when physical stress and consumer pressure were relatively low

because neighbors buffer one another from extremes of the abiotic environment (e.g., tem-

perature or salinity) and herbivory.

In support of the abiotic stress hypothesis, Bertness and Yeh (1994) found that the effects

of I. frutescens shrubs on conspecific seedlings were positive because soil salinity was

moderated by the shade of the benefactors in a New England salt marsh. When patches

were watered, however, strong competitive interactions developed between adults and seed-

lings, and among seedlings. Interactions between I. frutescens plants were dependent on

environmental conditions, competing more intensely under mild abiotic conditions and

facilitating each other when abiotic conditions were harsh. Bertness and Shumway (1993)

also eliminated the facilitative effects of D. spicata and Spartina patens on J. gerardi by

watering experimental plots and reducing soil salinity. In the same marsh, the fitness of Iva

shrubs associated with J. gerardi was enhanced by neighbors at lower elevations but strongly

suppressed by the same species at higher elevations where soil salinity was lower (Bertness

and Hacker 1994).

The relationship between abiotic stress and shifts in competition and facilitation has been

shown in other systems. Pugnaire and Luque (2001) found that facilitation effects decreased

quickly from strongly arid to more mesic sites, whereas competition remained constant but

changed from underground in the dry site to aboveground in the more mesic site. In inter-

mountain grasslands of the northern Rockies, Lesquerella carinata is positively associated

with bunchgrass species in relatively xeric areas, but negatively associated with the same

species in relatively mesic locations (Greenlee and Callaway 1996). They studied these spatial

patterns experimentally and documented shifts between interference and facilitation between

years at a xeric site. Bunchgrasses interfered with L. carinata, in a wet and cool (low-stress)

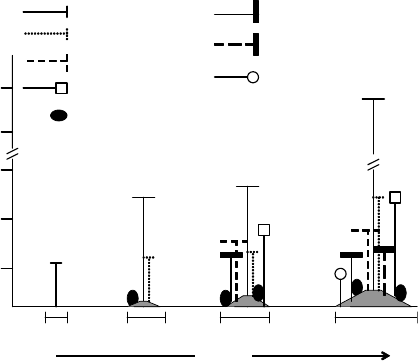

year, but facilitated Lesquerella in a dry and hot year (Figure 14.3). Other, nonexperimental,

studies indicate that competitive effects are stronger in wet, cool years and facilitative in

dry, hot years (Fuentes et al. 1984, De Jong and Klinkhamer 1988, Frost and McDougald

1989, McClaran and Bartolme 1989, Belsky 1994). In contrast to these studies, Casper (1996)

examined survival, growth, and flowering of Cryptantha flava in experiments explicitly

designed to test for shifts in positive and negative interactions with neighboring shrubs and

found no evidence that competition or facilitation changed as soil water varied between years.

Survival, %

0 50 100 1500 50 100 150

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

Days after plantin

g

Canopy

Clipped canopy

Artificial shade

Open

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 14.3 Effects of bunchgrasses and artificial canopies on the survival of Lesquerlla carinata in a

wet year (a) and in a dry year (b) in western Montana. (From Greenlee, J. and Callaway, R.M., Am.

Nat., 148, 386, 1996. With permission.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 445 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

Facilitation in Plant Communities 445

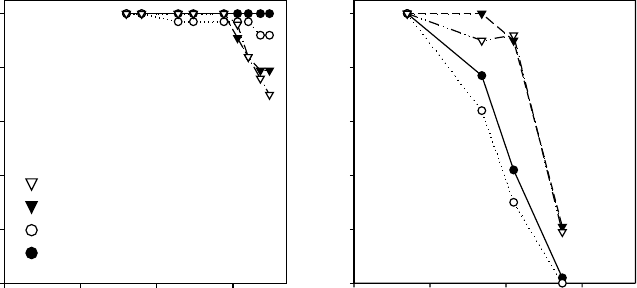

Strong shifts between competition and facilitation with stress have been shown on alpine

elevational gradients (Callaway et al. 2002). They found that competition generally, but not

exclusively, dominated interactions at lower elevations where conditions are less physically

stressful. In contrast, at high elevations where abiotic stress is high the interactions among

plants were predominantly positive (Figure 14.4).

Shifts in interspecific interactions have also been found to occur at different tempera-

tures in anaerobic substrates. M. laxa appeared to benefit from soil oxygenation when grown

with T. latifolia at low soil temperatures (Callaway and King 1996). But at higher soil

temperatures, Typha had no effect on soil oxygen (presumably due to increased microbial

and root respiration), and the interaction between Typha and Myosotis became competitive.

Changes in interspecific interactions may occur in a different sequence. Haase et al.

(1996) have shown that coexisting A. barrelieri and R. sphaerocarpa shrubs compete during

early stages of succession in abandoned semiarid fields in south-east Spain, but after

a time period during which Artemisia is competitively displaced, this subshrub is found prefer-

entially under the canopy of larger Retama shrubs. The pattern of the interaction suggested that

facilitation prevailed over competition because of niche separation that developed over time.

Complex combinations of negative and positive interactions operating simultaneously

between species appear to be widespread in nature. Such concomitant interactions in which

current conceptual models of interplant interactions are based on resource competition alone

may not accurately depict processes in natural plant communities.

P = 0.991

*

P = 0.009

*

P < 0.001

*

*

P = 0.354

*

P < 0.001

**

**

P < 0.001

**

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low Hi

g

h

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

RNE

−1.0

−0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

Low High

P = 0.405

**

P = 0.029

*

P < 0.001

*

**

P < 0.001

**

**

P < 0.001

**

**

FIGURE 14.4 Relative Neighbor Effect (RNE) at the 11 experimental sites. Error bars represent

one standard error, P values denote significance of differences between the two sites (ANOVA with

site and species as main effects), and asterisks denote a site effect that was significantly different from

zero (P > 0.01). (Reprinted from Callaway, R.W., Brooker, C.P.Z., Kikvidze, C.J., Lortie, R., Michalet,

L., Paolini, F.I., Pugnaire, B.J., Cook, E.T., Aschehong, C. Armas, and Newingham, B., Nature, 417,

844, 2002. With permission.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 446 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

446 Functional Plant Ecology

ARE BENEFACTOR SPECIES INTERCHANGEABLE?

The species-specificity of positive interactions among plants, or whether or not benefactor

species are interchangeable, is crucial to understanding of positive interactions and interde-

pendence in plant communities (Callaway 1998a). In other words, are the positive effects of

plants simply due to the alteration of the biophysical environment that can be imitated by

inanimate objects? Or can facilitation depend on the species, with some species eliciting strong

positive effects and other, morphologically similar, species producing no effect?

Spatial associations between beneficiaries and benefactors are often disproportional to

the abundance of potential beneficiaries. For example, Hutto et al. (1986) reported that

saguaros were distributed nonrandomly among potential nurse plants at two locations in

Organ Pipe National Monument in the Sonoran Desert, USA. They found that saguaros were

proportionally more abundant under many species of shrubs and trees, but significantly more

saguaros were associated with P. juliflora (mesquite) and paloverde trees and less saguaros

were associated with L. tridentata (creosote bush) than expected based on the proportional

cover of these species.

Suza

´

n et al. (1996) identified a large number of aborescent, shrub, and cacti species as nurse

plants of O. tesota (ironwood) in the Sonoran Desert of Mexico and the USA, and argued that,

as a habitat modifier, Olneya is a keystone species for biodiversity (also see Burqu

´

ez and

Quintana 1994). They described 30 species as shade-dependent, with 5 preferring Cercidium

species, 4 preferring Prosopis species, and 22 preferring O. tesota. Franco and Nobel (1989)

found that most saguaro seedlings in their Sonoran Desert study sites were associated with

C. microphyllum and Ambroisa deltoidea. In contrast, a second cactus species, the exceptionally

heat-tolerant F. acanthodes was preferentially associated with a bunchgrass, Hilaria rigida.

In Californian shrubland and woodland Q. agrifolia and Q. douglasii seedlings are dispro-

portionally associated with shrub species, and experimental manipulations have demonstrated

the importance of nurse shrubs for the survival of both species (Callaway and D’Antonio 1991,

Callaway 1992). However, not all shrubs had positive effects on Q. agrifolia; 43% of germin-

ating seedlings survived under Ericameria ericoides, 34% under Artemisia californica, 5% under

Mimulus auranticus, and 0% under Lupinus chamissonis (Callaway and D’Antonio 1991).

In other studies, the species of the benefactor plant does not seem to matter. For example,

Steenberg and Lowe (1969) reported that 15 different species can apparently act as nurse

plants for saguaro and are found associated with saguaro seedlings in proportion to their

frequencies, indicating that no specific biotic factor is involved, and that the nurse plant

association is only the by-product of microclimatic changes under canopies. Greenlee and

Callaway (1996) found that L. carinata, a small perennial herb, was commonly found under

the canopies of bunchgrasses on xeric sites in western Montana. However, Lesquerella was

distributed among bunchgrass species in proportion to their abundances.

Potential benefactor species (those with similar morphologies) may have specific effects on

beneficiaries simply because they alter the physical environment differently. For example, Suza

´

n

et al. (1996) attributed the disproportional positive affect of O. tesota to the fact that it is the only

tall evergreen aborescent in the region and ameliorates climatic conditions throughout the year.

Because facilitation occurs in complex combinations with competition, potential benefac-

tor species may have the same positive effect, but vary in their negative effects. For example,

Suza

´

n et al. (1996) suggested that Olneya’s superior facilitative ability may be due to its

phreatophytic life history and deeply distributed root architecture, thus reducing niche

overlap (e.g., Cody 1986) and accentuating positive mechanisms.

The consistently poor performance of creosote bush as a nurse plant in the Sonoran

Desert (Hutto et al. 1986, McAuliffe 1988) may be due to the strong negative effects this

species has on perennial neighbors (Fonteyn and Mahall 1981). Mahall and Callaway (1991,

1992) found that creosote bush substantially inhibited the root elongation rates of A. dumosa,

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 447 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

Facilitation in Plant Communities 447

and that these negative effects were reduced by the addition of small amounts of activated

carbon, a strong adsorbent to organic molecules (Cheremisinoff and Ellerbusch 1978). Thus

creosote bush canopies may have the potential to facilitate shade-requiring plants, but

prospective beneficiaries may be eliminated by root allelopathy. In the Chihauhan Desert,

however, L. tridentata has been reported to faciliate Opuntia leptocaulis (Yeaton 1978).

Muller (1953) documented strong positive associations between A. dumosa and many species

of desert annuals; however, Encelia farinosa shrubs did not harbor any annual species.

He attributed this difference to the allelopathic effect of Encelia leaves.

Pugnaire et al. (1996b) showed that edaphic conditions and productivity improved in the

understory of R. sphaerocarpa shrubs with age and that there was a replacement of species

under Retama canopies with a clear successional trend. The species found under the youngest

shrubs were also found in gaps and, as soil fertility increased and aspects of microclimate

(particularly irradiance and temperature) were ameliorated, different species colonized the

understory, including agricultural weeds and perennials. Growth conditions improved for

Retama itself, and there was an increase in cladode mass, photosynthetic area, and fruit

production with age, supporting the hypothesis that overstory shrubs benefit from the

understory herbs, and that indirect interactions between R. sphaerocarpa and its understory

herbs could be considered as a two-way facilitation in which both partners benefit from their

association (Pugnaire et al. 1996a).

Species that have similar affects on understory microclimate may vary in their affects on

soil nutrients creating species-specific effects. Turner et al. (1966) found that saguaro seedlings

survived better on soil collected from under paloverde trees than on those from under either

mesquite or O. tesota; however, these differences were confounded by soil albedo and

temperature.

Some facilitative mechanisms are produced by unusual plant traits, and thus infer a high

degree of species-specificity. For example, some of the strongest positive effects are produced

by protection from herbivores (Atsatt and O’Dowd 1976, McAuliffe 1984a, 1986, Hay 1986).

Repelling consumers requires specific morphological traits such as spines or tough tissues, or

the possession of chemical defenses. Not all potential benefactors in a community have

these traits.

Many of the traits described earlier such as oxygen transport (Callaway and King 1996),

shared pollinator attraction (Thomson 1978, Laverty 1992), hydraulic lift (Richards and

Caldwell 1987, Dawson 1993), and positive effects mediated through fungal intermediaries

(Grime et al. 1987, Marler et al. 1999) are not shared by all large number of species in a

community, suggesting that benefactors are not highly interchangeable.

POSITIVE INTERACTIONS AND COMMUNITY THEORY

The consistent observation of independent distributions of plant species along environmental

gradients (the individualistic-continuum) is a cornerstone of plant community theory

(Goodall 1963, McIntosh 1967, Austin 1990). Plant species are almost never completely

associated with another species at all points on environmental gradients, and so community

ecologists have long assumed that the distributions of plant species are determined by their

idiosyncratic responses to the abiotic environment and interspecific competition. However,

some evidence suggests that plant species may have some degree of interdependence at some

points on gradients, yet interact individualistically at others (Callaway 1998b).

Pinus albicaulis (whitebark pine) and Abies lasiocarpa (subalpine fir) dominate the

upper end of many xeric elevation gradients in the Northern Rockies (Daubenmire 1952,

Pfister et al. 1977). In many places, P. albicaulis is the dominant species at or near timberline,

but it also overlaps with A. lasiocarpa at lower elevations where the latter is more abun-

dant. Thus, these two species exhibit the classic continuum that is the cornerstone of the

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 448 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

448 Functional Plant Ecology

individualistic-continuum theory. However, a more detailed examination of interactions

between these species creates a more complex picture. P. albicaulis appears to have a

cumulative competitive effect on A. lasiocarpa at lower elevations, where there are no

significant spatial associations and the death of P. albicaulis corresponds with higher A.

lasiocarpa growth rates (Callaway 1998a). But at timberlines in xeric areas, A. lasiocarpa

is highly clumped around P. albicaulis, and the death of the latter is associated with decreased

A. lasoicarpa growth rates. Similar processes are also apparent in alpine communities of the

central Caucasus Mountains. Kikvidze (1993, 1996) measured numerous significant positive

spatial associations and found evidence for facilitation via amelioration of abiotic stress. At

high elevations, significant positive spatial associations are four times more common than

negative associations. However, at low elevations gradient-positive spatial associations were

four times less common than negative associations.

Variations for virtually all important types of interspecific interactions have been shown

to vary with changes in abiotic conditions. These include predation (Martin, in press), herbiv-

ory (Maschinski and Whitham 1989), parasitism (Gibson and Watkinson 1992, Pennings and

Callaway 1996), mutualism (Bronstein 1994), competition (Connell 1983, Kadmon 1995),

and allelopathy (Tang et al. 1995).

Shifting positive and negative interactions on environmental gradients indicates that

nodes, or fully overlapping discreet groups of species, are not required to demonstrate some

level of interdependence among plants in a community. Because plants can have neutral or

negative effects on neighbors at one point on an environmental gradient and positive effects at

another, and the positive effect of benefactors are often not interchangeable among species, a

continuum does not necessarily infer fully individualistic relationships among plant species.

The ubiquity of facilitative interactions in plant communities indicates the necessity of explicit

reconsideration of formal community theory. Lortie et al. (2004) proposed the concept of the

integrated community (IC) allowing natural plant communities to range from highly

individualistic to highly interdependent depending on synergism among: (i) stochastic pro-

cesses, (ii) the abiotic tolerances of species, (iii) positive and negative interactions among

plants, and (iv) indirect interactions within and between trophic levels. Rejecting strict

individualistic theory may allow ecologists to better explain variation occurring at different

spatial scales, synthesize more general predictive theories of community dynamics, and

develop models for community-level responses to global change.

CONCLUSION

Positive interactions are common in nature, and are caused by many different mechanisms

that are substantially different from those involved in competition. Positive interactions

co-occur with competition and the overall effect of one plant on another is often determined

by the balance of several mechanisms in a particular abiotic environment. In many cases,

positive interactions are highly species-specific and benefactors are not interchangeable,

suggesting that plant communities may be more interdependent than has been thought

since the widespread acceptance of Gleasonian individualistic communities. Furthermore,

plants may have strong competitive effects on a neighbor at one end of its distribution along a

physical gradient, but strong positive effects on the same neighbor at the other end. This

confounds interpretation of continuous distributions of plants in gradient analyses as evi-

dence for fully individualistic plant communities and supports the concept that plant com-

munities are real entities (Van der Maarel 1996). The growing body of evidence for positive

interactions in plant communities, and its theoretical framework, suggests that facilitation

plays important roles in determining the structure, diversity, and dynamics of many plant

communities.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C014 Final Proof page 449 18.4.2007 9:45pm Compositor Name: BMani

Facilitation in Plant Communities 449