Principles of Finance with Excel (Основы финансов c Excel)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PFE, Chapter 3: Capital budgeting 55

19. Kane Running Shoes is considering the manufacturing of a special shoe for race walking

which will indicate if an athlete is running (i.e. both legs are not touching the ground). The chief

economist of the company presented the following calculation for the Smart Walking Shoes

(SWS):

•

R&D $200,000 annually in each of the next 4 years.

The Manufacturing project:

•

Expected life span: 10 years

•

Investment in machinery: $250,000 (at t=4) expected life span of the machine 10 years

•

Expected annual sales: 5,000 pairs of shoes at the expected price of $150 per pair

•

Fixed cost $300,000 annually

•

Variable cost: $50 per pair of shoes

Kane’s discount rate is 12%, the corporate rate is 40%, and R&D expenses are tax deductible

against other profits of the company. Assume that at the end of project (that is. after 14 years)

the new technology will have been superseded by other technologies and therefore have no

value.

a) What is the NPV of the project?

b) The International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided to give Kane a loan without

interest for 6 years in order to encourage the company to take on the project. The loan

will have to be paid back in 6 equal annual payments. What is the minimum loan that the

IOC should give in order that the project will be profitable?

PFE, Chapter 3: Capital budgeting 56

20. (Continuation of previous problem) After long negotiations the IOC decided to lend Kane

$600,000 at t=0. The project went ahead. After the research and development stage was

completed (at t=4) but before the investment was made, the IOC decided to cancel race walking

as an Olympic event. As a result Kane is expecting a large drop in sales of the SWS shoes.

What is the minimum number of shoes Nike has to sell annually for the project to be profitable in

each of the following two cases:

a) If in the event of cancellation the original loan term continues?

b) If in the event of cancellation the company has to return the outstanding debt to the

IOC immediately?

21. The Aphrodite company is a manufacture of perfume. The company is about to launch a

new line of products. The marketing department has to decide whether to use an aggressive or

regular campaign.

Aggressive campaign

Initial cost - (production of commercial advertisement using a top model): $400,000

First month profit: $20,000

Monthly growth in profit (month 2-12): 10%

After 12 months the company is going to launch a new line of products and it is expected

that the monthly profits from the current line would be $20,000 forever.

Regular Campaign

Initial cost (using a less famous model) $150,000

First month profit: $10,000

PFE, Chapter 3: Capital budgeting 57

Monthly growth in profits (month 2-12): 6%

Monthly profit (month 13-

∞ ): $20,000

a) The cost of capital is 7%. Calculate the NPV of each campaign and decide which

campaign should the company undertake.

b) The manager of the company believes that due to the recession expected next year, the

profit figures for the aggressive campaign (both first month profit, and 2-12 profit

growth) are too optimistic. Use data table in order to show the differential NPV as a

function of first month payment and growth rate of the aggressive campaign.

22. The Long-Life company has a 10 year monopoly for selling a new vaccine that is capable of

curing all known cancers. The demand for the new drug is given by the following equation:

P= 10,000 - 0.03X ,

where P is the price per vaccine and X is the quantity. In order to mass-produce the new drug

the company needs to purchase new machines. Each machine costs $70,000,000 and is capable

of producing 500,000 vaccines per year. The expected life span of each machine is 5 years; over

this time it will be depreciated on a straight-line basis to zero salvage value. The R&D cost for

the new drug is $1,500,000,000, the variable costs are $1,000 per vaccine, fixed costs are

$120,000,000 annually. If the discount rate is 12% and the tax rate is 30%, how many vaccines

will the company produce annually? (Use either Excel’s

Goal Seek or its Solver—see Chapter

32.)

23. (Continuation of problem 22) The independent senator from Alaska Michele Carey has

suggested that the government will pay Long-Life $2,000,000 in exchange for the company

PFE, Chapter 3: Capital budgeting 58

guaranteeing that it will produce under the zero profit policy. (i.e. produce as long as NPV>=0).

How many vaccines will the company produce annually?

PFE, Chapter 6, Weighted average cost of capital page 1

CHAPTER 6: DERIVING THE WEIGHTED AVERAGE

COST OF CAPITAL (WACC)

*

this version: May 18, 2003

Chapter contents

Overview......................................................................................................................................... 1

6.1. What does the firm’s WACC mean? ...................................................................................... 5

6.2. The Gordon dividend model: discounting anticipated dividends to derive the firm’s cost of

equity r

E

.......................................................................................................................................... 7

6.3. Applying the Gordon cost of equity formula—Courier Corporation ................................... 11

6.4. Calculating the WACC for Courier ...................................................................................... 17

6.5. Two uses of the WACC........................................................................................................ 22

Summing up.................................................................................................................................. 29

Exercises....................................................................................................................................... 31

Overview

In Chapter 5 we discussed general principles of deriving discount rates. The basic

principle is that the discount rate for a stream of cash flows should be appropriate to the riskiness

of the cash flows. Although the measurement of risk is still vague (we will be specific about

*

Notice: This is a preliminary draft of a chapter of Principles of Finance by Simon Benninga

(benninga@wharton.upenn.edu

). Check with the author before distributing this draft (though

you will probably get permission). Make sure the material is updated before distributing it. All

the material is copyright and the rights belong to the author and MIT Press.

PFE, Chapter 6, Weighted average cost of capital page 2

measuring risks only in Chapters 10 – 15), we saw in Chapter 5 that we often have a good

intuitive feel for what constitutes a similar risk investment, and that this intuition allows us to

determine a discount rate. For example, an investment whose cash flows are almost certain

should be discounted at the bank lending rate. A real estate investment, on the other hand,

should be discounted at the average rate of return we’re likely to get from other, similar and

risky, real estate investments.

In this chapter we discuss the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). The WACC is

the average rate of return the firm has to pay its shareholders and its lenders. The WACC is

often the appropriate risk-adjusted discount rate for a company’s cash. Here are two examples:

• White Water Rafting Corporation is considering buying a new type of raft. The raft is

more expensive than the existing rafts operated by the company because it is self-

sealing—holes in the raft are automatically and permanently fixed by a new technology.

During the rafting season, White Water’s existing rafts spend a considerable amount of

down time having their punctures fixed, and the company anticipates that the new self-

sealing rafts will improve its profitability by increasing efficiency and decreasing costs.

By being the first rafting company on the river to have the self-sealing rafts, White Water

hopes to attract business away from other rafting companies—customers naturally hate to

have their trips interrupted by “flat rafts” (the rafting equivalent of a “flat tire”), and

when they hear of White Water’s new rafts, they will prefer White Water over its

competitors.

The White Water financial analyst has derived the set of anticipated cash flows for the

new raft. To complete the NPV analysis, the company needs to decide on an appropriate

discount rate. Here’s where the WACC comes in: Since the riskiness of the cash flows

PFE, Chapter 6, Weighted average cost of capital page 3

from the new rafts is similar to the riskiness of White Water Rafting’s existing cash

flows, the WACC is an appropriate discount rate.

• Gorgeous Fountain Water Company (GF) sells bottled water from the Gorgeous Fountain

natural spring. The company is considering buying Dazzling Cascade Water Company.

Dazzling Cascade (DC) operates in a neighboring area to that dominated by GF, and its

operations, sales, and anticipated cash flows have been thoroughly analyzed by the

Gorgeous Fountain financial analysis staff.

In order to value DC, GF has to decide on an appropriate discount rate for the anticipated

DC cash flows. Here’s where the weighted average cost of capital comes in. GF’s

WACC is the average rate of return demanded by its investors; assuming that the

riskiness of DC’s cash flows is similar to that of GF, the WACC is an appropriate

discount rate for the GF cash flows. Discounting the DC cash flows at GF’s WACC

allows Gorgeous Fountain to establish a bid price for Dazzling Cascade.

Some important terminology before we start

When we talk about “firms” in this book we generally mean corporations, companies that

have shareholders and debtholders.

1

A typical firm is incorporated, which means that it is a legal

entity which is separate from its shareholders and debtholders. The income of a corporation is

taxed at the corporate income tax rate.

The shareholders own stock in the firm. When the firm is profitable, management may

decide to pay dividends to the shareholders, but these dividend payments are not guaranteed.

Shareholders can also sell their shares and in doing so may make a profit (called a “capital gain”)

1

Equivalent terminology for shareholders: stockholders, equity owners; for debtholders: lenders, bondholders.

PFE, Chapter 6, Weighted average cost of capital page 4

or a loss. As you can see, the cash flows of a shareholder in a firm are uncertain. The

shareholders in the firm have limited liability; they are not responsible for repaying the

debtholders if the firm cannot do so out of its cash flows.

The cost of equity, denoted r

E

, is the discount rate applied by shareholders to their

expected future cash flows from the firm. It goes without saying that this cost of equity

depends—like the cost of equity of our real-estate investment in Chapter 5—both on the

riskiness of the firm’s free cash flows. The higher the riskiness of the shareholder’s expected

future cash flows, the higher the cost of equity r

E

.

The firm’s debtholders are its lenders. Debtholders are promised a fixed return (interest)

on their lending to the firm. The debtholders may be banks, who have lent money to the firm, or

they may be individuals or pension funds who have bought the firm’s bonds. The interest

payments to the firm’s debtholders are expenses for tax purposes. The interest payments on the

firm’s debt and the firm’s tax rate determine the after-tax cost of debt for the firm, which we

denote r

D

(1-T).

Finance concepts discussed

• Cost of equity, r

E

and the Gordon dividend model

• Cost of debt, r

D

Excel functions used

• This chapter uses no interesting Excel functions!

PFE, Chapter 6, Weighted average cost of capital page 5

6.1. What does the firm’s WACC mean?

The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is the average return that the company

has to pay to its equity and debt investors. Another way of putting this is that the WACC is the

average return shareholders and debtholders expect to receive from the company.

2

The

definition of the WACC is:

()

the percentage the percentage

of equity used to of debt used to

finance the firm finance the firm

*1*

where

'-- '

EDC

E

D

ED

WACC r r T

ED ED

r the firm s cost of equity the return required by the firm s shareholders

rth

↑↑

=+−

++

=

=

'-- '

'

'

'

C

e firm s cost of debt the return required by the firm s debtholders

E market value of the firm s equity

D market value of the firm s debt

T the firm s tax rate

=

=

=

Here’s a simple example to show what we mean: United Transport Inc. has 3 million

shares outstanding; the current market price per share is $10. The company has also borrowed

$10 million from its banks at a rate of 8%; this is the company’s cost of debt r

D

. United

Transport has a tax rate of T

C

= 40%.

3

The company thinks its shareholders want an annual

2

In finance the expected return, the required return, the cost of capital (be it cost of equity or cost of debt), the

required rate of return are all synonyms. They all represent the market-adjusted rate that investors get (or demand)

on various investments or securities.

3

We use the symbol T

C

to indicate the corporate tax rate.

PFE, Chapter 6, Weighted average cost of capital page 6

return on their investment of 20%; this 20% return is the company’s cost of equity r

E

.

4

To

compute United Transport’s WACC we use the formula:

()

()

20%

8%

3,000,000 $10 $30,000,000

$10,000,000

40%

*1*

30 10

20%* 8%* 1 40% * 16.2%

30 10 30 10

E

D

C

EDC

r

r

E shares each worth

D

T

ED

WACC r r T

ED ED

=

=

==

=

=

=+−

++

=+− =

+

+

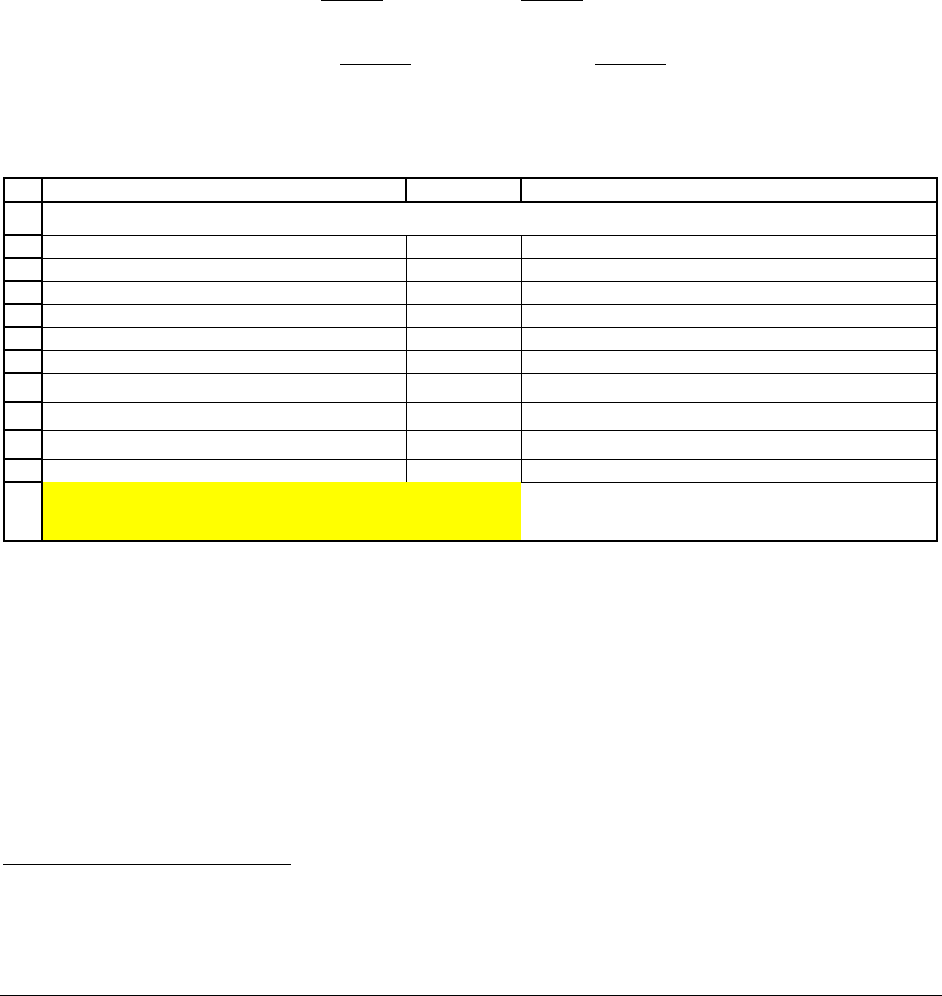

In a spreadsheet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

AB C

Number of shares 3,000,000

Market price per share 10

E, market value of equity 30,000,000 <-- =B3*B2

D, market value of debt 10,000,000

r

E

, cost of equity

20%

r

D

, cost of debt

8%

T

C

, firm's tax rate

40%

WACC, weighted average cost of capital:

WACC=r

E

*E/(E+D)+r

D

*(1-T

C

)*D/(E+D)

16.20% <-- =B8*B5/(B5+B6)+B9*(1-B10)*B6/(B5+B6)

UNITED TRANSPORT--WACC

The United Transport WACC computation shows you that the WACC depends on five

critical variables.

•

r

E

, the cost of equity. r

E

is the return required by the firm’s shareholders. Of the five

parameters in the WACC calculation, r

E

is the most difficult to calculate. A model for

calculating r

E

is given in Section 6.2.

4

How did United Transport come to the conclusion that its shareholders want a 20% return? This is the question in

the computation of the WACC, and we will spend a lot of this chapter discussing the answer. So be patient!