Perrie M. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

michael s. flier

inferior position; a society is rededicated to the possibility of resurrection after

death. Such are the psychological and spiritual transformations rituals bring

about.

The political life of Muscovite society was replete with rituals. Perhaps

the most daunting was kissing the cross (krestnoe tselovanie) in a church to

solemnify an oath or declaration as true. Princes forged alliances, confirmed

treaties and attested wills by kissing the cross. Litigants in court disputes

without clear evidence faced the terrifying prospect of standing before the

cross, kissingit the fateful third time, and swearing the truth of their testimony.

Frequently they opted for other forms of resolution.

2

The ritual of petition produced different relationships. In describing ritual

practice at the Muscovite court in the early sixteenth century, Sigismund von

Herberstein, the ambassador of the Holy Roman Emperor, wrote:

whenever anyone makes a petition, or offers thanks, it is the custom to bow

the head; if he wishes to do so in a very marked manner, he bends himself so

low as to touch the ground with his hand; but if he desires to offer his thanks

to the grand-duke for any great favour, or to beg anything of him, he then

bows himself so low as to touch the ground with his forehead.

3

This ritual, combined with references to petitioners as slaves (kholopy) and the

ruler as master (gosudar’), convinced many foreigners, including Herberstein,

that Muscovy was a despotic state. Bit’ chelom ‘to beat one’s forehead’ was,

after all, the Muscovite term for paying obeisance and the source for chelobitie

(chelobit’e) ‘petition’, literally beating of the forehead.

Cross kissing was a Kievan and Muscovite ritual that confirmed a relation-

ship of obeisance before God, rendering all persons, high and low, equal before

their creator. The beating of the head, by contrast, was a ritual that confirmed

an asymmetrical relationship, rendering petitioner and petitioned unequal in

status and affirming the political and social hierarchy of Muscovite life.

Muscovy and the ideology of rulership

The correlation of ritual and political ideas begins with the historical trans-

formation of Muscovy and the development of a myth to account for it. By

2 Giles Fletcher, ‘Of the RusseCommonwealth’, in Lloyd E. Berry and Robert O. Crummey

(eds.), Rude and Barbarous Kingdom: Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voy-

agers (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968), pp. 174–5; Nancy Shields Kollmann,

By Honor Bound: State and Society in Early Modern Russia (Ithaca, N. Y.: Cornell University

Press, 1999), pp. 119–20.

3 Sigismund von Herberstein, Notes upon Russia, 2 vols., trans. R. H. Major (New York:

Burt Franklin, 1851–2), vol. ii,pp.124–5.

388

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Political ideas and rituals

the mid-fifteenth century, Moscow was adjusting to an altered position in the

world of Eastern Orthodoxy. Rejecting the Union of Florence and Ferrara, the

Muscovites refused to consult the Greeks when selecting their new metropoli-

tan in 1448 and in effect formed an autocephalous Orthodox Church. There-

after, the Muscovite Church promulgated an anti-Tatar, anti-Muslim campaign

in the chronicles in counterpoint to the pure Christian tradition represented

by Moscow.

4

Moscow was increasingly portrayed as inheriting the legacy of

Kievan Rus’ and with it, the myth of the Rus’ian Land, which was ultimately

incorporated into the myth of the Muscovite ruler.

5

Constantinople’s capture

by the Turks in 1453 and the seemingly providential expansion of the Muscovite

principality thereafter opened new vistas for Ivan III when he ascended to

thethronein 1462.By1480, ArchbishopVassianRylo wasurging himto become

the great Christian tsar and liberator of the Rus’ian Land, the ‘New Israel’, in

its struggle against the Golden Horde, the ‘godless sons of Hagar’.

6

Theideology that crystallised in Muscovyduring the reigns of Ivan III (1462–

1505), his son, Vasilii III (1505–33) and grandson, Ivan IV (1533–84) presented the

Byzantine notion of the emperor-dominated realm as the Kingdom of Christ

on Earth. If allusion to Agapetus gave the ruler absolute political authority

over the state (‘though an emperor in body be like all other men, yet in power

he is like God’), the Epanag

¯

og

¯

e of Patriarch Photius and other Byzantine polit-

ical literature known in Muscovy at the time broadly demarcated spheres of

authority apportioned among temporal and spiritual leaders.

7

Church polemi-

cists such as Iosif Volotskiiin The Enlightener praised the power and authority of

the grand prince, but insisted on the mobilisation of wise advisers – temporal

and spiritual – against authority that transgressed the laws of God.

8

Muscovite rulership and the Kievan legacy were expressed most clearly

in the invented tradition of The Tale of the Princes of Vladimir (c.1510). The

4 Donald Ostrowski, Muscovy and the Mongols: Cross-Cultural Influences on the Steppe Frontier,

1304–1589 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 164–70.

5 Charles J. Halperin, ‘The Russian Land and the Russian Tsar: The Emergence of Mus-

covite Ideology, 1380–1408’, FOG 23 (1976): 79–82; Jaroslaw Pelenski, ‘The Origins of the

Official Muscovite Claims to the “Kievan Inheritance” ’, HUS 1 (1977): 40–2, 51–2 and ‘The

Emergence of the Muscovite Claims to the Byzantine-Kievan “Imperial Inheritance” ’,

HUS 7 (1983): 20–1.

6 PSRL, vol. viii (Moscow: Iazyki russkoi kul’tury, 2001), pp. 212–13.

7 Deno John Geanakoplos, Byzantine East & Latin West: Two Worlds of Christendom in

Middle Ages and Renaissance, Studies in Ecclesiastical and Cultural History (New York: Harper

Torchbooks, 1966), pp. 63–5; Ostrowski, Muscovy and the Mongols,pp.207–8.

8 David M. Goldfrank, The Monastic Rule of Iosif Volotsky, rev. edn, Cistercian Studies Series,

no. 36 (Kalamazoo, Mich., and Cambridge, Mass.: Cistercian Publications, 2000), p. 42;

Daniel Rowland, ‘Did Muscovite Literary Ideology Place Limits on the Power of the Tsar

(1540s–1660s)?’, RR 49 (1990): 126–31; Ostrowski, Muscovy and the Mongols,pp.199–218.

389

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

michael s. flier

Roman genealogy that traced the Riurikid dynasty back to Prus, a kinsman of

Augustus Caesar, may have been included to assure Europeans that the use of

the term ‘tsar’ for the Muscovite ruler was legitimate. The Monomakh legend

provided a Byzantine pedigree for Muscovite Orthodox rulership in the form

of concrete royal symbols of authority sent by Byzantine emperor Constantine

Monomachos to Vladimir Monomakh to be used at the latter’s installation as

Kievan grand prince.

9

In theory the Muscovite ruler had unlimited power and authority in ren-

dering God’s will, but in practice he governed with the support and close

involvement of a secular and ecclesiastical elite.

10

It was this ruling elite that

faced the imminent Apocalypse at the approach of 1492, the portentous year

7000 in the Byzantine reckoning. In this context, the city of Moscow itself

was reconceptualised in Orthodox Christian terms as the New Jerusalem and

Muscovy came to be understood as the embodiment of the Chosen People,

whose ruler chosen by God was prepared to lead them to salvation.

11

Ritual and setting

In three centuries Moscow had evolved from a mere outpost to a city with

a walled fortress and pretensions to greatness. By the 1470s, the earlier struc-

tures built to mark the rise of a city – limestone walls, stone churches, royal

palace and halls – were dilapidated.

12

Ivan III, better than any of his immediate

predecessors, understood how setting and ritual might serve to integrate the

notions of the emerging Muscovite state and a ruling elite. In an impressive

environment, solemn rituals could elevate the person of the ruler and help

confirm his position at the apex of society. There was no place more suitable

for rituals of high purpose than the Kremlin, the fortress of Moscow.

Cathedral Square was one of the semiotically most charged spaces within

the Kremlin (see Figure 17.1). It was bounded on the north by the cathedral

9 Ostrowski, Muscovy and the Mongols,pp.171–6.

10 Edward L. Keenan, ‘Muscovite Political Folkways’, RR 45 (1986): 128–36; Nancy Shields

Kollmann, Kinship and Politics: The Making of the Muscovite Political System, 1345–1547

(Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1987), pp. 146–87; Kollmann, By Honor Bound,

pp. 169–202; Ostrowski, Muscovy and the Mongols,pp.85–107, 135–43, 199–218.

11 Ostrowski, Muscovy and the Mongols,p.218; Michael S. Flier, ‘Till the End of Time: The

Apocalypse in Russian Historical Experience before 1500’, in Valerie A. Kivelson and

Robert H. Greene (eds.), Orthodox Russia: Belief and Practice under the Tsars (University

Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003), pp. 152–8.

12 I. E. Grabar’ (ed.), Istoriia russkogo iskusstva, 13 vols. (Moscow: AN SSSR, 1953–64), vol.

iii (1955), pp. 282–333; T. F. Savarenskaia (ed.), Arkhitekturnye ansambli Moskvy XV–nachala

XX vekov: Printsipy khudozhestvennogo edinstva (Moscow: Stroiizdat, 1997), pp. 17–53.

390

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Political ideas and rituals

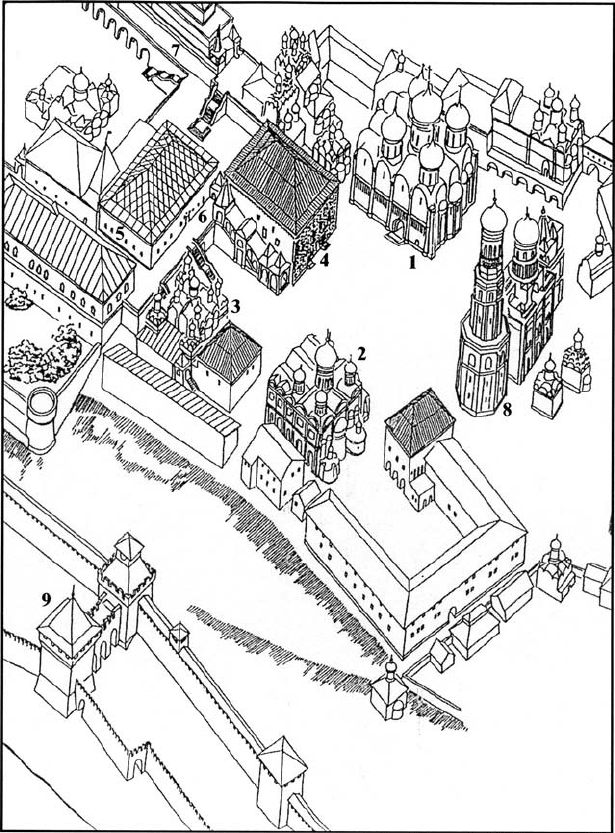

Figure 17.1. Cathedral Square, Moscow Kremlin

KEY: 1. Cathedral of the Dormition

2. Cathedral of Archangel Michael

3. Cathedral of Annunciation

4. Faceted Hall

5. Golden Hall

6. Beautiful (Red) Porch

7. Palace

8. Bell Tower ‘Ivan the Great’

9. Tainik Tower

391

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

michael s. flier

of the Dormition (primary cathedral church), on the east by the bell tower

‘Ivan the Great’, on the south by the cathedral of the Archangel Michael (royal

necropolis), and on the west by the cathedral of the Annunciation (palace

church), the Golden Hall (throne room), the adjacent Beautiful (Red) Porch

and Staircase, and the Faceted Hall (reception hall).

The cathedral of the Dormition (1475–9) was designed by Bolognese archi-

tect Aristotele Fioravanti after the Muscovite effort to rebuild resulted in a

disastrous collapse in 1474.

13

Fioravanti reshaped the older Vladimir Dormi-

tion plan in a Renaissance compositional key, maintaining modified medieval

Vladimir-Suzdal’ features on the exterior. He created a dramatic southern por-

tal facing Cathedral Square, harmonised the dimensions of the bays, flattened

the apses, and produced a characteristically north-eastern limestone fac¸ade

that prompted contemporaries to describe the buildingas though carved ‘from

a single stone’.

14

He opened up the internal space to the highest vaults, elim-

inating the gallery that would traditionally have ensconced the royal family.

The place of the grand prince was relocated to the ground floor near the

southern portal, which became an effective alternative point of egress for the

ruler during processions.

The Metropolitan’s Pew, mentioned in many of the Dormition’s rituals,

was apparently installed between 1479 and the mid-1480s in a space adjacent

to the south-east pillar of the nave facing the iconostasis.

15

More than seven

decades passed before the self-standing Tsar’s Pew was installed on 1 Septem-

ber 1551, four years after Ivan IV was officially crowned as the first tsar. Better

known as the Monomakh Throne, the Pew boasted twelve carved wooden

panels based on excerpts from the Monomakh legend taken from The Tale of

the Princes of Vladimir. Apart from military forays against the Byzantines, the

panels depicted Monomakh in consultation with a boyar council, the arrival of

the royal Byzantine regalia in Kiev, and their use in the crowning of Vladimir

Monomakh as grand prince, all messages immediately relevant to Muscovite

ideology. The theme of Jerusalem was represented in the inscription around

the cornice, which reproduced God’s injunction about dynastic continuity and

wise rulership to King David and King Solomon. Furthermore, the compo-

sition of the Pew bore a clear affinity to the Dormition’s Small Zion, a silver

13 See historical survey with source references in V. P. Vygolov, Arkhitektura Moskovskoi Rusi

serediny XV veka (Moscow: Nauka, 1988), pp. 177–210.

14 PSRL, vol. xxv (Moscow and Leningrad: AN SSSR, 1949), p. 324.

15 T. V. Tolstaia, Uspenskii sobor Moskovskogo Kremlia (Moscow: Nauka, 1979), p. 30;

G. N. Bocharov, ‘Tsarskoe Mesto Ivana Groznogo v Moskovskom Uspenskom sobore’,

in Pamiatniki russkoi arkhitektury i monumental’nogo iskusstva: Goroda, ansambli, zodchie,

ed. V. P. Vygolov (Moscow: Nauka, 1985), p. 46.

392

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Political ideas and rituals

liturgical vessel representingJerusalem’s Holy Sepulchre and carried in solemn

processions.

16

Thecathedral of ArchangelMichael (1505–8) wasdesignedbyanother Italian

architect, Alevisio the Younger. He retained the asymmetrical bays from the

earlier medieval plan, but added striking Renaissance ornament, including

limestone articulation against a red-brick fac¸ade and distinctive, large scallop-

shell gables signifying rebirth. This was fitting symbolism for a site devoted

to the memory of the royal dynasty, whose sarcophagi occupied the southern

and later northern part of the nave and a side chapel near the sanctuary.

The cathedral of the Annunciation (1484–9) had been rebuilt by native Psko-

vian architects, who skilfully combined the basic Suzdalian articulated cube

with its blind arcade frieze and ogival gables together with brickwork and

design redolent of Pskov and Novgorod, a stylistic marriage signalling Mus-

covite success in ‘the gathering of the Rus’ian lands’.

The Faceted Hall (1487–91) was designed by Italians Marco Ruffo and Pietro

Antonio Solario in the style of a northern Italian Renaissance palazzo, but

with an obvious allusion to its namesake in Novgorod. Named after the carved

facets on the eastern fac¸ade facing the Square, it was notable for its internal

design with a huge central pier supporting groined vaults. The pier served as

a staging area for official receptions and banquets hosted by the grand prince.

TheFacetedHallisoftenmentionedinforeignaccountsasthesite of numerous

rituals of status and conciliation as regards foreign audiences, seating protocol,

the tasting and distribution of food and the proposing of toasts.

17

The Golden Hall was planned by Ivan III but completed by his son, Vasilii

III, in 1508. Reached off a great landing, the Beautiful (Red) Porch overlooking

Cathedral Square, the Golden Hall consisted of a vestibule, where dignitaries

gathered, and the throne room. The name was apparently inspired by the

Chrysotriklinos, the Golden Hall throne room of the Byzantine emperor in

Constantinople. Severely damaged in the Moscow fire of 1547, the Golden

Hall was completely rebuilt by order of the newly crowned tsar, Ivan IV, and

decorated with elaborate and controversial murals that referred to allegories

and historical events important to Muscovite ideology.

18

16 I. A. Sterligova, ‘Ierusalimy kak liturgicheskie sosudy v Drevnei Rusi’, in Ierusalim v

russkoi kul’ture, ed. Andrei Batalov and Aleksei Lidov (Moscow: Nauka, 1994), p. 50;

Michael S. Flier, ‘The Throne of Monomakh: Ivan the Terrible and the Architectonics

of Destiny’, in James Cracraft and Daniel Rowland (eds.), Architectures of Russian Identity

1500 to the Present (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003), pp. 30–2.

17 Herberstein, Notes, vol. ii,pp.127–32; Richard Chancellor, ‘The First Voyage to Russia’,

in Berry and Crummey (eds.), Rude and Barbarous Kingdom,pp.25–7.

18 O. I. Podobedova, Moskovskaia shkola zhivopisi pri Ivane IV: Raboty v Moskovskom Kremle

40-kh–70-kh godov XVI v. (Moscow: Nauka, 1972), pp. 59–68; David B. Miller, ‘The

393

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

michael s. flier

ThemajorarchitecturalinnovationbeyondtheKremlinitselfwasthechurch

of the Intercession on the Moat, later known as St Basil’s cathedral. Built in

Beautiful (Red) Square in celebration of Ivan IV’s victory over the Kazan’

khanate in 1552, the church underwent a slow progression in 1555 from indi-

vidual shrines to a composite set of correlated chapels, which, taken together,

resemble Jerusalem in microcosm.

19

Completed in 1561 on a site adjacent to

the central marketplace and the world of the non-elite, the Intercession stood

as an antipode to the core structures of Cathedral Square behind the Kremlin

walls.

In 1598/9, just to the north of the Intercession, a raised round dais was built

in stone, possibly replacing an earlier wooden structure.

20

Called Golgotha

(Lobnoe mesto ‘place of the skull’), it was a site for major royal proclamations,

including declarations of war, announcements of royal births and deaths and

the naming of heirs apparent,perhaps replacing the original city tribune. It was

also used as a station for major cross processions led by the chief prelate and

the tsar, rituals featuring the palladium of Moscow, the icon of the Vladimir

Mother of God, in honour of her benevolent protection. Golgotha, by its

very name and placement near the Intercession ‘Jerusalem’, made manifest

Moscow’s self-perception as the New Jerusalem.

The political rituals that realised most directly the myth of the Muscovite

ruler and his realm were either contingent, prompted by circumstance, or cycli-

cal, governed by the ecclesiastical calendar. They were direct, requiring the

presence of the ruler, or indirect, referring to his office. In addition to the

actual protocols of ceremony, the locus of performance, whether inside or

outside Moscow and its golden centre, provided significant points of refer-

ence that guided and enriched the message intended. Nowhere is this better

demonstrated than in the etiquette involving foreign diplomats, from whom

we have quite extensive responses.

21

Viskovatyi Affair of 1553–54: Official Art, the Emergence of Autocracy, and the Disin-

tegration of Medieval Russian Culture’, RH 8 (1981): 298, 308, 314–20; Michael S. Flier,

‘K semioticheskomu analizu Zolotoi palaty Moskovskogo Kremlia’, in Drevnerusskoe

iskusstvo.Russkoeiskusstvopozdnegosrednevekov’ia:XVI vek(StPetersburg:Dmitrii Bulanin,

2003), pp. 180–6; Daniel Rowland, ‘Two Cultures, One Throneroom: Secular Courtiers

and Orthodox Culture in the Golden Hall of the Moscow Kremlin’, in Kivelson and

Greene (eds.), Orthodox Russia: Belief and Practice under the Tsars,pp.40–53.

19 Michael S. Flier, ‘Filling in the Blanks: The Church of the Intercession and the Architec-

tonics of Medieval Muscovite Ritual’, HUS 19 (1995): 120–37; Savarenskaia (ed.), Arkhitek-

turnye ansambli Moskvy, pp. 54–99.

20 PSRL, vol. xxxiv (Moscow: AN SSSR, 1978), p. 202; B. A. Uspenskii, Tsar’ i patriarkh:

Kharizma vlasti v Rossii (Vizantiiskaia model’ i ee russkoe pereosmyslenie) (Moscow: Iazyki

russkoi kul’tury, 1998), p. 455 (n. 52).

21 Marshall Poe, ‘A People Born to Slavery’: Russia in Early Modern Ethnography, 1476–1748

(Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2000), pp. 39–81.

394

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Political ideas and rituals

Contingent rituals

Foreign diplomatic rituals

In a report that resonates with others from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

writers, Herberstein commented on the indirect but nonetheless elaborate

ritual etiquette that faced foreign embassies upon approaching Muscovite

territory.

22

Each part of the protocol – initial contact, local interview, delay

for instructions from Moscow, escort, entrance into Moscow, sequestering

and audience with the Muscovite ruler – confirmed relative status. Ritual

gestures such as dismounting from horses or sledges, or the baring of heads in

anticipation of verbal exchange, were carried out in a specific order, designed

to place the prestige of the Muscovite representative, and indirectly that of the

grand prince, above that of the foreign visitor and his master.

Royal escorts rode ahead of and behind the embassy along the entire route,

allowing no one to fall behind or join the entourage. Symbolically the royal

reachextendedtotheverybordersoftherealm,envelopingtheforeignelement

and drawing it towards the centre. At each station new representatives were

dispatched from the centre to receive the members of the embassy and greet

them in the name of the ruler until at last, after several days or even weeks of

waitingoutside the city, theywereescorted into Moscow past crowds of people

intentionally brought there. Entering the Kremlin on foot, they encountered

huge numbers of soldiers and separate ranks of courtiers – enough people, so

Herberstein reasoned,to impressforeignerswith the sheer quantity of subjects

and the consequent power of the grand prince. The closer the envoys came to

the site of the grand prince, the more frequent were the successions of ever

more highly placed ranks of nobility, each rank moving into position directly

behind the embassy as the next higher one waited to greet them.

Once ushered into the throne room itself, the envoys descended several

steps to the floor. From this position they were obliged to look up at the

sumptuously attired ruler on a raised throne. Additionally they confronted

his numerous courtiers, clad in golden cloth down to their ankles, the boyars

resplendent in their high fur hats, and all seated on benches above the steps

against the other three walls in an orderly array.

23

The English merchant

Richard Chancellor reported that ‘this so honorable an assembly, so great a

majesty of the emperor and of the place, might very well have amazed our

men and have dashed them out of countenance. . .’

24

The papal legate to

22 Herberstein, Notes, vol. ii,pp.112–42.

23 Chancellor, ‘First Voyage’, p. 24.

24 Ibid., p. 25.

395

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

michael s. flier

Ivan IV, Antonio Possevino, judged that in the splendour of his court and

those who populate it, the tsar ‘rivals the Pope and surpasses other kings’.

25

TheEnglishcommercialagent JeromeHorseynoted with admirationIvanIV’s

four royal guards (ryndy) flanking the throne, dressed in shiny silver cloth and

bearing ceremonial pole-axes.

26

The carefully arranged hierarchy of courtiers

dominated by the tsar was all-encompassing and meant to impress visitors

with the size, authority and immeasurable wealth of the Muscovite court. All

petitioners were required to repeat the ruler’s lengthy series of titles, a list

based on rank and geographic spread. Omission of any title on the list was not

tolerated.

27

The most important ceremonial act during the audience was the

diplomat’s kissing of the tsar’s right hand, if it was offered.

28

Ritual enquiries

about health were then followed by the formal presentation of gifts by the

diplomat.

Royal progresses

As a complement to the ritualised travel of diplomats towards the centre,

the royal progress from centre to periphery allowed the ruler himself to pro-

mulgate Muscovite ideology by travelling to cities, towns and monasteries

in elaborate processions, with icons and other ecclesiastical accoutrements.

29

Such a ritual stamping out of territory and creation of royal space tied the

land to the ruler through contiguity. Participating in impressive ceremonies of

entrance (adventus) and departure (profectio), the ruler was able to take posses-

sion of the site physically and spiritually by means of an awe-inspiring display

of the sort demonstrated by Ivan IV when he captured and entered Kazan’ in

1552 and then returned to Moscow in a triumphant procession.

30

Bride shows

The authority of the ruler was represented directly or indirectly in rituals

intended to preserve harmony and balance among the court elite. Marriage

25 Antonio Possevino, The Moscovia of Antonio Possevino, S.J.,ed.andtrans.HughF.Graham,

UCIS Series in Russian and East European Studies, no. 1 (Pittsburgh: University Center

for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 1977), p. 47.

26 Sir Jerome Horsey, ‘Travels’, in Berry and Crummey (eds.), Rude and Barbarous Kingdom,

p. 303.

27 Fletcher, ‘Russe Commonwealth’, pp. 131–2; cf. Herberstein, Notes, vol. ii,pp.34–8.

28 L.A. Iuzefovich, ‘Kak v posol’skikh obychaiakh vedetsia’ (Moscow: Mezhdunarodnye

otnosheniia, 1988), pp. 115–16.

29 Nancy Shields Kollmann, ‘Pilgrimage, Procession, and Symbolic Space in Sixteenth-

Century Russian Politics’, in Michael S. Flier and Daniel Rowland (eds.), Medieval

Russian Culture, 2 vols. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), vol. ii,pp.163–6.

30 PSRL, vol. xiii (Moscow: Iazyki russkoi kul’tury, 2000), pp. 220–8.

396

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Political ideas and rituals

arrangements, for instance, helped maintain a tenuous power network among

specific clans at court. The intricate organisation of bride shows, performed

ritually before the ruler, guaranteed him and his family firm control over

the selection process and the relationships to be strengthened, weakened or

ended.

31

Surrender-by-the-head ritual

The indirect ritual of surrender by the head (vydacha golovoiu) was intended

to confirm the hierarchy among elites established by the rules of precedence

(mestnichestvo) and is described in Kotoshikhin’s seventeenth-century account

of the Muscovite court.

32

Violators of precedence were sent in disgrace on foot

instead of on horseback from the Kremlin, a metonym of the tsar’s power, to

the house of the offended party, wherethe tsar’s representatives announced the

ruler’s decision to the winner as he stood on an upstairs porch. The semiotic

oppositions of low and high were complemented by the loser’s permission to

insult the winner for emotional release without retaliation. The ritual rein-

forcedtheimageoftheruleras charismatic and autocratic, and that ofthenoble

elite as accommodating and supportive advisers committed to preserving the

order and stability that made government by consensus possible.

33

Coronation ritual

Althoughwehave no recordof the investitureceremonyof the grand princes of

Kievan Rus’ or of their counterparts in Muscovite Rus’ before the late fifteenth

century, some form of installation ceremonysurelyexisted. The direct formula

that appears in chronicle accounts simply notes that such-and-such a prince

assumed authority (siede lit. ‘sat’) in a given capital or that a more highly placed

ruler installed him on the throne (posadi lit. ‘seated’).

The earliest evidence of an actual coronation ceremony in Muscovy dates

from 4 February 1498, when a ritual based on the Byzantine ceremony for co-

emperors was used to lend legitimacy to Ivan III’s naming a controversial heir

apparent – grandson Dmitrii rather than second son Vasilii – to the Muscovite

throne. By 1502, Vasilii had regained favour and was named grand prince

and thus entitled to succeed his father. Interestingly, the performance of the

coronation ceremony had not guaranteed the succession to Dmitrii, thus

31 Russell E. Martin, ‘Dynastic Marriage in Muscovy, 1500–1729’, unpublished Ph.D. disser-

tation, Harvard University, 1996,pp.30–110.

32 Grigorij Koto

ˇ

sixin, O Rossii v carstvovanie Alekseja Mixajlovi

ˇ

ca: Text and Commentary,

ed. A. E. Pennington (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980), fos. 63–64v, 67, 149, 150.

33 Nancy Shields Kollmann, ‘Ritual and Social Drama at the Muscovite Court’,SR 45 (1986):

497–500.

397

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008