Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 5: U-Z

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WARHOLENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

81

Campbell’s Soup I, screenprint by Andy Warhol.

Avenue. Warhol’s position as the leading Pop artist was consolidated

in 1962 at the seminal ‘‘New Realists’’ exhibition at the Sidney Janis

Gallery in New York. After 1964, Warhol was represented by the

New York dealer Leo Castelli, who also handled most of the other

Pop artists.

Warhol quickly became notorious for his paintings of Camp-

bell’s Soup cans, which were first exhibited at Los Angeles’ Ferus

Gallery in 1962. These paintings were straightforward renderings of

row upon row of soup cans. Not just publicity gambits, these were

important avant-garde works, signaling a major change in the nature

of art. They were a cool reaction to the passionate—and to the Pop

artists’ minds, excessive—art of the Abstract Expressionists, which

then dominated the art scene. The soup cans were painted in the same

spirit as Marcel Duchamp’s ‘‘readymades’’ (objects designated as

artworks merely by the artist’s choice and recontextualization).

Warhol was forced to defend the paintings as legitimate artworks

when the Campbell Soup Company sued the him for copyright

infringement. The corporation later decided that the paintings were

good advertising. In 1963, inspired by the objects he had seen in

supermarkets, Warhol precisely imitated Brillo soap-pad boxes. He

had one-hundred wooden boxes constructed by a carpenter and

stenciled the sides with exact imitations of the Brillo graphic. For sale

at three hundred dollars each, these created great excitement when

they were exhibited at Manhattan’s Stable Gallery the following year.

When they were to be shown in a Toronto art gallery, their status as art

was ignored. Warhol’s dealer had to pay ‘‘merchandise duty’’ to have

them delivered.

With works like these Warhol had abandoned painting by hand

for other more anonymous techniques (such as photo-silkscreen). ‘‘I

want to be a machine,’’ he said in 1962, subverting the idea of the

artist as an expressive medium who creates unique, handmade works.

Warhol used Marilyn Monroe as a motif in several silk-screened

works in the 1960s (as in Gold Marilyn Monroe [1962, The Museum

of Modern Art, New York]). Rendered in the cheap-looking, off-

register style of trashy reproduction, these artworks suggested that

Marilyn’s manufactured persona had overwhelmed her identity as a

person. Celebrities became a major theme in Warhol’s works. Through-

out the next two decades he made images of athletes, politicians, and

entertainers such as Elvis Presley, Troy Donahue, Jackie Kennedy

Onassis, Elizabeth Taylor, and Chairman Mao. As in the Marilyn

images, the colors were often garish and silk-screened off-register. A

series from this period is entitled Ten Portraits of Jews of the

Twentieth Century. Warhol’s fascination with stars was reflected in

the gossipy celebrity magazine he founded in 1969 entitled Inter/

View, then Andy Warhol’s Interview, and later simply Interview.

In response to the civic strife of the 1960s, Warhol created his

Disaster series. Such works as Car Crash, Race Riot, and Electric

Chair involve the stark appropriation of newspaper photographs

saturated with color and often repeated within the same frame.

Warhol suggested that in these works he wished to demonstrate how

the callous repetition of the media’s coverage of traumatic events

creates a numbing apathy in viewers.

In 1964 Warhol established his ‘‘Factory,’’ a rented attic that

became a large mass-production studio in New York where assistants

made works serially. It was responsible for turning out thousands of

Warhol’s works. Often, Warhol would clip photos from magazines

and newspapers and have them silk-screened by his assistants. The

very name ‘‘factory’’ challenged the notion of an artist’s studio as a

place of inspiration, a place where unique and precious pieces are

made. In this spirit, Warhol once said that anybody ‘‘should be able to

do all my paintings for me.’’ The Factory became nearly as notorious

for its denizens as the art that was produced there. Robert Hughes

described its silver-papered walls as a place where ‘‘cultural space-

debris, drifting fragments from a variety of Sixties subcultures

(transvestite, drug, S & M, rock, Poor Little Rich, criminal, street, and

all the permutations) orbiting in smeary ellipses around their un-

moved mover.’’ Shy and inhibited himself, Warhol became a voyeur

of a subculture of his own creation. In his role as funky entrepreneur

Warhol opened a nightclub with the thoroughly 1960s-sounding

name ‘‘The Exploding Plastic Inevitable,’’ whose house-band was

The Velvet Underground. Its leader, Lou Reed, is now regarded as a

soulful guru of heroine culture and musically a pioneer of Punk and

New Wave.

In a decade racked by assassinations, Warhol himself was shot

on June 3, 1968, by Valerie Solanis, a former Factory groupie turned

militant feminist. The only member of S.C.U.M. (‘‘The Society for

Cutting Up Men’’), Solanis later claimed that she did so because the

artist ‘‘had too much control over her life.’’ The scars of several bullet

wounds to Warhol’s chest are depicted in Alice Neel’s well known

portrait of the artist. Ominously, a woman had shot at one of Warhol’s

portraits of Marilyn Monroe four years earlier.

WASHINGTON ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

82

At the time of his first solo exhibition in 1965, at the Institute of

Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, it was announced that Warhol had

given up painting to concentrate on filmmaking. Throughout the

1960s the artist made several movies which have become classics of

film history and of Minimalist cinema. Typically, they are outra-

geously boring and amateurish—qualities for which they are ad-

mired—and register the spontaneous exhibitionism of his Factory

‘‘actors.’’ Eat (1964) showed artist Robert Indiana eating a mush-

room. Empire (1964) was comprised of an eight-hour shot of one side

of the Empire State Building in New York (the changing light is its

only action). In 1964 Film Culture magazine awarded him their

Independent Film Award. In all, Warhol collaborated on more than

seventy-five films. His highly-regarded The Chelsea Girls (1966)

was the first underground film to be shown at a conventional

commercial theater. On a split screen viewers watched a quirky kind

of documentary: the comings and goings of Warholian ‘‘superstars’’

in two different hotel rooms. Four Stars (1966-67) ran for more than

twenty-four hours and was shown using three projectors simultane-

ously on one screen. The films My Hustler (1965), Bike Boy, and

Lonesome Cowboys (both 1967) all dealt with homosexual themes.

Paul Morrissey, a production assistant and occasional cameraman in

the Factory, participated significantly in many of Warhol’s films. He

was enlisted to give them a greater sense of structure and profession-

alism, and to make them more appealing to a popular audience, as in

Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein (1974). Starting in 1980, Warhol was

briefly interested in video; he worked to establish a private cable

television station called ‘‘Andy Warhol TV.’’

As his works indicate, Warhol was genuinely obsessed with

celebrity, and particularly Hollywood fame. In the 1970s and 1980s

he seems to have given himself over to the popular media. He was

often seen at Studio 54, and at nearly every opening and award

ceremony. He appeared almost nightly on Entertainment Tonight

escorting Brooke Shields, Bianca Jagger, Elizabeth Taylor, or the

designer Halston. Not only attracted by the celebrity of entertainers,

Warhol also courted rising young artists such as the graffiti artists

Keith Haring (1958-1990) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988). In

the film Basquiat (directed by Julian Schnabel, 1997), rock star David

Bowie plays a convincing Warhol in a vivid depiction of the 1980s

New York art scene. In line with other artists of the 1980s who

‘‘appropriated’’ imagery from art history, Warhol made a series of

paintings based on famous works by Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci.

Like his films, Warhol’s untimely death seemed anticlimactic,

even banal. He died of complications after a fairly routine operation

on February 22, 1987. The auction of his possessions, in itself a

cultural event, revealed that Warhol had always been an impassioned

collector. His extensive collection of folk art had been exhibited in

1977 at the Museum of Modern Art. His influence as an arbiter of

taste continued even after his death. The sale of his possessions,

including his collections of all manner of kitschy art and furnishings,

influenced the retro styles of the late 1980s and 1990s. Today the

Estate of Andy Warhol handles his artworks and their reproduction.

The meaning of Warhol’s art has been endlessly debated and

alternately seen to be tremendously deep or mind-numbingly superfi-

cial. The artist often mystified interviewers by affecting a profound

detachment—often to the point of boredom. In one early interview the

artist explained, ‘‘If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just

look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am.

There’s nothing behind it.’’ Warhol will always be associated with

those aspects of 1960s popular culture that involve outrageous

behavior, a sensationalist media, and the art world as glitzy big

business. His most famous pronouncement, ‘‘in the future everybody,

will be famous for fifteen minutes,’’ seems an accurate observation

about the media’s insatiable appetite for creating quickly consumable

media targets.

—Mark B. Pohlad

F

URTHER READING:

Bockris, Victor. Life and Death of Andy Warhol. New York, Da Capo

Press, 1997.

Cagle, Van M. Reconstructing Pop/Subculture: Art, Rock, and Andy

Warhol. Thousand Oaks, California, Sage Publications, 1995.

Francis, Mark, and Margery King. The Warhol Look: Glamour, Style,

Fashion. Boston, Little, Brown, 1997.

Hackett, Pat, editor. The Andy Warhol Diaries. New York, Warner

Books, 1989.

Honnef, Klaus. Andy Warhol, 1928-1987: Commerce into Art, trans-

lated from the German by Carole Fahy and I. Burns. Cologne,

Benedikt Taschen, 1993.

Koch, Stephan. Stargazer: The Life, World and Films of Andy

Warhol. New York, Rizzoli, 1991.

Ratcliff, Carter. Andy Warhol. New York, Abbeville Press, 1983.

Shanes, Eric. Warhol. London, Studio Editions, 1993.

Tretiack, Philippe. Andy Warhol. New York, Universe Books, 1997.

Washington, Denzel (1954—)

A handsome, intelligent, and stylish actor, Denzel Washington is

the natural heir, with a modern edge, to Sidney Poitier, the first film

star to have demonstrated that an African American could become a

heartthrob and a top box-office draw in the United States. Born in

Mount Vernon, New York, Washington holds a B.A. in journalism

from Fordham, studied acting at San Francisco’s American Conser-

vatory Theater, and worked on stage and in television (he was an

ongoing character in the popular hospital series, St. Elsewhere) before

Hollywood beckoned. He made his screen debut as white George

Segal’s black illegitimate son in Carbon Copy (1982). Five years

later, his portrayal of South African political activist Steve Biko in

Cry Freedom (1987) brought him stardom and an Oscar nomination

for Best Supporting Actor. He won that award, and a Golden Globe,

for his embittered but courageous runaway slave in Glory (1989). He

has made several other films dealing with the issue of race; from the

comedic (Heart Condition, 1990) through the romantic (Mississippi

Masala, 1991) to the overtly political, as the title character in Spike

Lee’s Malcolm X (1993). He has, however, established his versatility

in a broad range of work, notably including Shakespeare—on screen

in Kenneth Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing (1993), and as

Richard III on stage in New York’s Central Park in 1990.

—Frances Gateward

WASHINGTON POSTENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

83

Denzel Washington

FURTHER READING:

Brode, Douglas. Denzel Washington: His Films and Career. Secaucus,

New Jersey, Carol Publishing Group, 1997.

Simmons, Alex. Denzel Washington. Austin, Texas, Raintree Steck-

Vaughn, 1997.

Simon, Leslie. ‘‘Why Denzel Washington (not Tom Cruise) is the

New Paul Newman.’’ Film Comment. Vol. 34, March/April

1998, 72-75.

Washington Monument

The Washington Monument’s tall, slender obelisk towers above

the Mall in the nation’s capitol, dominating the skyline. A grateful

public constructed it in the nineteenth century to commemorate

George Washington. Federal architect Robert Mills won a competi-

tion in 1845 with his proposal for a 600-foot obelisk and circular

temple at the base. The monument was completed in 1884 without the

temple and 45 feet shorter than Mills’s design. Unlike the capitol’s

other presidential monuments, the Washington Monument is abstract,

with no images or words; its power comes from the simple beauty of

its form. It has been largely uncontroversial, which is unique for a

political monument. And unlike the nearby Lincoln Memorial, the

Washington Monument has not been the site of any significant

political events. Instead, it has stood for over 100 years in quiet

solemnity as a proud testament to ‘‘the Father of our country.’’

—Dale Allen Gyure

F

URTHER READING:

Liscombe, Rhodri Windsor. Altogether American: Robert Mills,

Architect and Engineer. New York, Oxford University Press, 1994.

Scott, Pamela. Temple of Liberty: Building the Capitol for a New

Nation. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995.

Scott, Pamela, and Antoinette J. Lee. Buildings of the District of

Columbia. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993.

The Washington Post

The story of the Washington Post is really the story of three

family members and one outsider who, over a period of four decades,

took a somnolent and bankrupt newspaper in the capital of the United

States and turned it into an icon of good journalism. The four people

are Eugene Meyer, his son-in-law, Philip Graham, Meyer’s daughter

and Graham’s wife, Katharine, and the man Katharine hired to be the

executive editor, Ben Bradlee. It is also the tale of two Pulitzer Prizes,

the yin and yang of the Post’s rise to fame.

The Washington Post, born in 1877, was undistinguished as a

journalistic organ for a good part of its first century of life. Eugene

Meyer bought the bankrupt paper in 1933 for $825,000 at an auction,

a time when there were four other more substantial dailies in

Washington and the premier paper was the Star. In fact, the Post’s

early history under Meyer does not suggest that anything but disaster

was in the cards because the paper continued to lose money, upwards

of a million dollars a year. But Meyer, who was independently

wealthy, stuck with the paper through thick and thin, saying: ‘‘In the

pursuit of truth, the newspaper shall be prepared to make sacrifices of

its material fortunes, if such course be necessary for the public good.’’

His daughter one day would show the same resolve for the good of

truth and to the paper’s benefit.

The daughter, however, did not start out to become a newspaper

publisher. When Katharine Meyer graduated from the University of

Chicago in 1938, she went to work as a reporter for the San Francisco

Examiner. But within a year, her father ordered her home to work at

the Post, although not with the intention that she would be groomed as

his successor. She eventually married Philip Graham, who became

publisher in 1947; he was 31 and Katharine was 29. Katharine

immediately took on the role of dutiful wife.

Her husband, in the meantime, following in his father-in-law’s

footsteps, got very involved in politics, and became something of a

king maker, which creates complications for reporters who are trying

to cover all sides of a story, not just the boss’s side. Shortly after

Graham took over, a young reporter named Ben Bradlee resigned

WASHINGTON POST ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

84

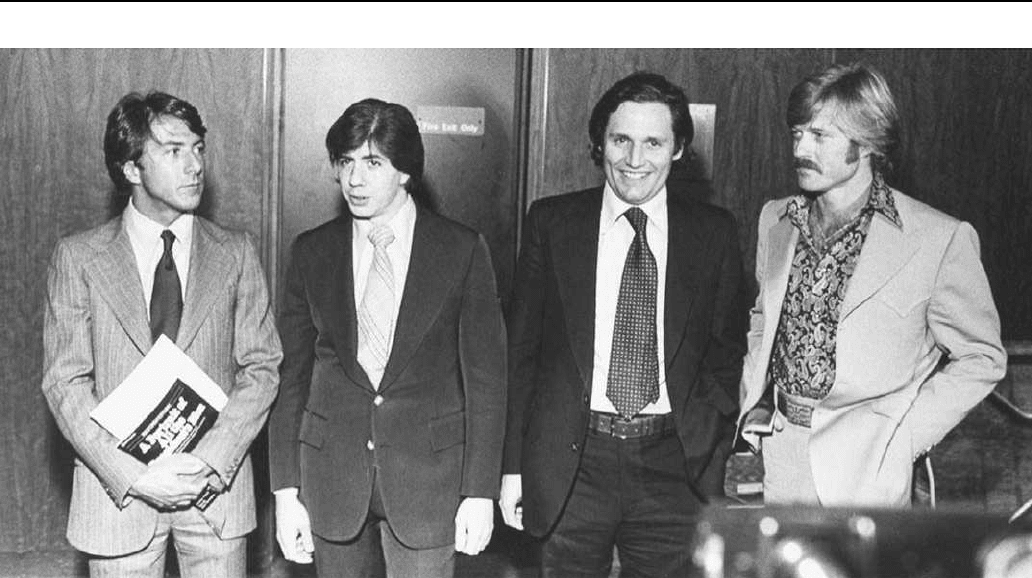

From left: Dustin Hoffman, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward of the Washington Post, and Robert Redford.

from the Post and joined the Washington bureau of Newsweek. The

Post continued to prosper, and Meyer bought out and shut down

another daily in Washington, reducing the number of dailies to three.

In 1961, the Post purchased Newsweek.

Two years later, Philip Graham killed himself—he was a manic

depressive—and Katharine Graham was thrust into the role of pub-

lisher of her late father’s newspaper. She was a quick study. Realizing

she needed to put her own team in place, she hired Bradlee and put

him on the fast track to become executive editor. The Post was

on its way.

The Post lived in the shadow of The New York Times, which had

a much longer tradition of journalistic greatness. The Times, a paper

that covered the federal government thoroughly, was a direct com-

petitor for the Post, and it showed that one day in 1971 when it started

to publish a series of stories about a top secret report that became

popularly known as ‘‘The Pentagon Papers,’’ in effect, scooping the

Post in it own backyard. The Post rose to the occasion, got its own

copy of the papers, and published parts unavailable to the Times,

thereby regaining its dignity, and also showing a measure of journal-

istic skill not seen before. When the federal government, through the

courts, enjoined both papers from publishing, the papers united to

fight in the Supreme Court for the right to publish and to maintain a

sacred constitutional principle that the government does not have the

right to censor. The newspapers won.

The Post reached national stature on its own a year later when it

began almost exclusive coverage of a break-in at Democratic Nation-

al Committee in a building called ‘‘The Watergate.’’ Essentially, it

was a local cops beat story that took on added importance when the

Post discovered that some of the Watergate burglars had worked for

CREEP—the Committee to Re-Elect the President. Not only was it a

great story, but the Post’s methodical unraveling of the machinations

of President Nixon’s henchmen set high standards for reporting. Two

young reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, sometimes

aided by an unidentified source in the executive branch who became

known as ‘‘Deep Throat,’’ dug through records and interviewed

hundreds of people to produce a series of stories that helped lead to

Richard Nixon’s resignation as president and to the Post’s winning a

Pulitzer Prize. The Post endured tremendous pressure to back off the

story (its material fortunes were threatened), but Katharine Graham

stood by her embattled newsroom and was eventually vindicated.

It has become part of the lore that Woodward and Bernstein

brought down a president, but that overlooks all that was going on

around President Nixon at the time. For example, one Watergate

burglar, threatened by a judge with a long jail sentence, in effect,

turned state’s evidence on his friends. Then there was a Senate

committee investigating what went on, and eventually, the House

Judiciary Committee approved articles of impeachment. There was

also the revelation that Nixon had taped many of his Oval Office

conversations, and when the Supreme Court ruled that Nixon had to

yield the tapes, he resigned. The Post did not single-handedly bring

down the president, but if it had ignored the break-in story, the other

facilitators might not have assumed their important roles.

As happens with so many on the way up, the Post became a

victim of is own hubris when it published in 1981 a story about an 8-

year-old boy named Jimmy, who supposedly used heroin. It was a

dramatic story, written by a young reporter named Janet Cooke and

published on the front page. The story created a controversy not

because the Post had published it, but because it had not tried to help

the boy; there was also churning inside the Post because the story had

been published on the word of the reporter—no one asked for her

sources and there was none of the double-checking that had made the

Watergate reporting an exemplary effort. It was only after the reporter

WATERGATEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

85

won a Pulitzer Prize that other journalists started to check her

credentials and discovered that she had lied about her education and

her degrees. And in her story, ‘‘Jimmy’’ was a fictional character, not

a real person. The Post returned the Pulitzer, and Cooke resigned.

The Post, however, has continued to be a great newspaper. It

made its mark with Watergate and stubbed its toe with Janet Cooke,

but its owners and editors knew which way they wanted the paper to

go and kept it on that track. Ironically, none of the newspapers that

circulated in Washington when Eugene Meyer purchased the bank-

rupt Post survived beyond 1981. The Post had proved itself.

—R. Thomas Berner

F

URTHER READING:

Bray, Howard. The Pillars of the Post: The Making of a News Empire

in Washington. New York, W.W. Norton, 1980.

Graham, Katharine. Personal History. New York, Alfred A.

Knopf, 1997.

Kelly, Tom. The Imperial Post: The Meyers, the Grahams and the

Paper That Rules Washington. New York, William Morrow, 1983.

Roberts, Chalmers M. The Washington Post: The First 100 Years.

Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1977.

Ungar, Sanford J. The Papers and the Papers. New York, E.P.

Dutton, 1972.

Watergate

On the evening of June 16, 1972, a security guard at the

Watergate Hotel in Washington, D.C., discovered a piece of tape on

the lock of the door that led to the National Democratic Headquarters

and set off a chain of events that would, ultimately, bring down the

presidency of Richard Milhous Nixon. Afterwards, Americans would

wonder why Nixon and the Republican party risked so much on such a

minor event when Nixon was leading in the election polls, and the

Democratic party was in disarray. Indeed, Nixon would go on to win

the presidency by a landslide, with 520 electoral votes. Only 270

electoral votes are needed to win the presidency.

The break-in at the Watergate was only part of a larger campaign

designed by Nixon supporters to rattle Democratic candidates and

tarnish the reputation of the whole party. This campaign included

harassment of Democratic candidates, negative campaign ads, two

separate break-ins at the National Democratic Headquarters, and an

additional break-in at Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office. Ellsberg

was the individual who offered up the ‘‘Pentagon Papers’’ for public

consumption, detailing the strategy—or lack of it—for the United

States’ position in Vietnam.

Theodore H. White, chronicler of presidents from Dwight Eisen-

hower to Ronald Reagan, points out in Breach of Faith that the

Watergate break-in was riddled with mistakes. G. Gordon Liddy,

advisor to Richard Nixon, had been given $83,000 from Nixon’s

Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP) to provide the neces-

sary equipment. When the tape was placed over the lock, it was placed

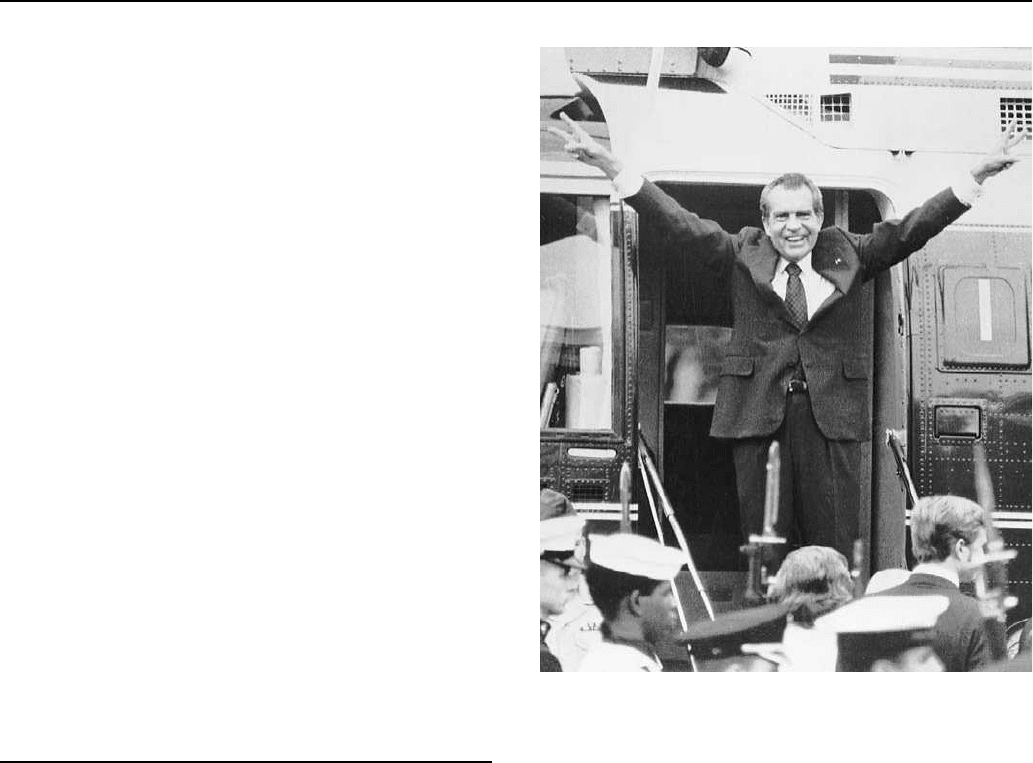

Richard Nixon leaving the White House after resigning the presidency

following the Watergate scandal.

horizontally rather than vertically, which made it more noticeable.

The tape had been spotted earlier in the day and removed by a security

guard. It was replaced in the same position. Since only outside

personnel were used for the break-in, they were easy to spot as not

belonging in the Watergate. The electronic surveillance equipment

purchased by Liddy was inferior and had no cut-off between those

conducting the actual break-in and those listening in another hotel

across the street. When the break-in was discovered, the police were

led to Howard Hunt and Liddy in a hotel across the street. Further-

more, all participants had retained their own identification papers.

Instead of being honest with the American public and taking his

advisors to task, Richard Nixon immediately became embroiled in a

cover-up that would slowly unravel over the next two years—leading

to Nixon’s resignation in August 1974. As the facts surrounding the

break-in were made known, it was revealed that the Nixon presidency

had been involved in serious manipulation and abuse of power for

years. It seemed that millions of dollars coming from Nixon support-

ers had been used to pay hush money in an ill-advised attempt to hide

the truth from Congress and the American people. Richard Nixon, it

was discovered, truly lived up to his nickname of ‘‘Tricky Dick.’’

During the investigation, the names of Richard Nixon’s advisors

would become as well known to the American people as those of

Hollywood celebrities or sports heroes. Chief among these new

celebrities were close friends of the President: John Ehrlichman and

Bob Haldeman. Ehrlichman served as the President and Chief of the

Domestic Council while Haldeman acted as Chief of Staff. Both

WATERS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

86

would be fired in a desperate attempt to save the presidency. Another

major player was John Dean, the young and ambitious Counsel to the

President. John Mitchell, the Attorney General, and his wife Martha

provided color for the developing story. Rosemary Woods, the

president’s personal secretary, stood loyally by as investigators kept

demanding answers to two questions: ‘‘What did the president

know?’’ and ‘‘When did he know it?’’ The answers to the two

questions provided the crux of the investigation. If it had been proved

that Nixon was the victim of over-enthusiastic supporters rather than a

chief player in the entire scenario, his presidency would have sur-

vived. When Nixon learned of the break-in was integral to under-

standing his part, if any, in the subsequent cover-up.

An investigation revealed that Nixon knew about the break-in

from the beginning and that he was involved in the cover-up as it

progressed. When the Nixon presidency was over, James David

Barber, political scientist and author of The Presidential Character,

detailed its crimes: ‘‘Making secret war; Developing secret agree-

ments to sell weapons to enemy nations; Supporting terroristic

governments; Helping to overthrow progressive governments; Re-

ceiving bribes; Selling high political offices; Recruiting secret White

House police force; Impounding sums of money appropriated by

Congress; Subverting the electoral, judicial, legal, tax, and free

speech systems; and Lying to just about everyone.’’

In the early days of the Watergate investigation, most forms of

media reported the break-in as a minor story with little national

significance. However, two aggressive young reporters who worked

for The Washington Post began to dig deeper into the background

surrounding the actual crime. Aided by an informant, who would be

identified only as ‘‘Deep Throat,’’ Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward

uncovered one of the major stories of the twentieth century and

became instrumental in forcing the first presidential resignation in

American history.

As Congress began to hold congressional hearings, Alexander

Butterfield, a Nixon presidential aide, revealed that a complex taping

system was in place, including in the Oval Office, Camp David, the

Cabinet rooms, and Nixon’s hideaway office. Nixon’s distrust of

others would prove to be his own undoing. He fought to maintain

control over the tapes and went so far as to fire a number of White

House officials in what became known as the ‘‘Saturday Night

Massacre.’’ The Supreme Court did not accept Nixon’s argument that

the tapes contained only private conversations between the president

and his advisors and, as such, were protected by executive privilege.

From the time in 1974 that the Court in U.S. v. Nixon ordered the

president to release the tapes, it was widely accepted that Nixon had

lost the presidency.

The tapes released in the 1970s contained 18 minutes of silence

that have never been explained. In 1996 the lawsuit of historian

Stanley I. Kutler and the advocacy group Public Citizen resulted in

the release of over 200 additional hours of tape. In Abuse of Power:

The New Nixon Tapes, Kutler writes that the new information reveals

that Nixon was intimately involved both before and after Watergate in

abuses of power. A taped conversation on June 23, 1972, proved that

Nixon and Haldeman talked about using the CIA to thwart the FBI

investigation into the cover-up. When the New York Times published

the ‘‘Pentagon Papers,’’ Nixon told his advisors: ‘‘We’re up against

an enemy conspiracy. They’re using any means. We’re going to use

any means.’’ This conversation goes a long way in illustrating

Nixon’s paranoia and his adversarial relationship with the American

citizenry. It also points out his belief in his own invincibility.

In mid-1974, after Nixon had been named an unindicted co-

conspirator in the Watergate affair, the House of Representatives

approved the following articles of impeachment: Article I: Obstruc-

tion of justice; Article II: Abuse of power; and Article III: Defiance of

committee subpoena. These charges arose from months of listening to

those involved in the Nixon presidency and the Watergate cover-up

explain the machinations of the Nixon administration. In order to save

themselves from serving time in prison, most Nixon cohorts were

willing to implicate higher-ups. Ultimately, Howard Hunt, G. Gordon

Liddy, James McCord, and four Cuban flunkies were convicted and

served time in jail.

Until the final days of his presidency, Richard Nixon insisted

that he would survive. When he recognized that it was over and that he

had lost, he went into seclusion. Reportedly, Alexander Haig, his

Chief of Staff, oversaw the dismantling of the presidency. On August

8, 1974, wearing a blue suit with a blue tie and a flag pin in his lapel,

Richard Nixon announced to the world that he no longer had a

political base strong enough to support his remaining time in office

and resigned the presidency. The following day, Vice President

Gerald Ford was sworn in as president of the United States.

Although it was a bitter and disillusioning time for the American

people, Watergate proved that democracy continues to work—and

that not even the president is above the law and the United

States Constitution.

—Elizabeth Purdy

F

URTHER READING:

Barber, James David. The Presidential Character: Predicting Per-

formance in the White House. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey,

Prentice Hall, 1992.

Bernstein, Carl, and Bob Woodward. All the President’s Men. New

York, Touchstone Books, 1994.

Fremon, David K. The Watergate Scandal in American History.

Springfield, New Jersey, Enslow Publishers, 1998.

Genovese, Michael A. The Watergate Crisis. Westport, Connecticut,

Greenwood Press, 1999.

Kutler, Stanley I., editor. Abuse of Power: The New Nixon Tapes.

New York, The Free Press, 1997.

Lukas, J. Anthony. Nightmare: The Underside of the Nixon Years.

New York, Viking, 1976.

Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr. The Imperial Presidency. New York,

Popular Library, 1974.

Schudson, Michael. Watergate in American Memory: How We Re-

member, Forget, and Reconstruct the Past. New York,

BasicBooks, 1992.

White, Theodore H. Breach of Faith: The Fall of Richard Nixon. New

York, Atheneum Press, 1975.

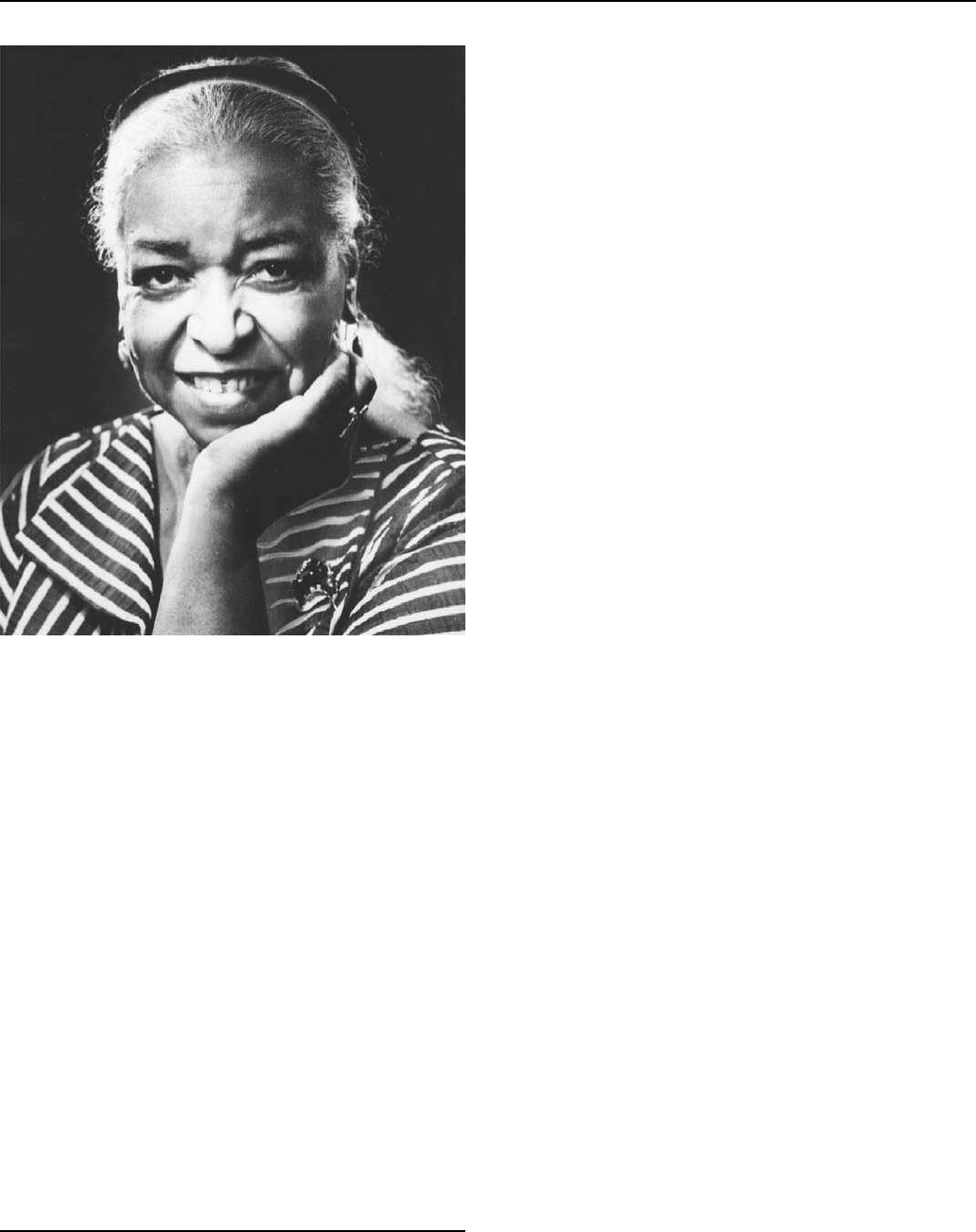

Waters, Ethel (1900-1977)

Born in turn-of-the-century Chester, Pennsylvania, black singer-

actor-entertainer Ethel Waters presided for nearly fifty years as one of

WATERSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

87

Ethel Waters

America’s most celebrated performers. She began her career as a

singer in 1917 at the Lincoln Theatre in Baltimore, Maryland. Billed

as ‘‘Sweet Mama Stringbean’’ during her early years as a ‘‘shimmy

dancer’’ and robust singer of heart-rending songs, her work traversed

stage, movie screen, radio, and television. Her memorable credits

include numerous Broadway reviews, the stage and screen versions of

Cabin the Sky (1943) and Member of the Wedding (1952), the 1949

film classic Pinky, and the title role in the Beulah television series

(1950-52).

—Pamala S. Deane

F

URTHER READING:

Waters, Ethel, with Charles Samuels, His Eye Is on the Sparrow: An

Autobiography. New York, Pyramid, 1967.

Knaack, Twila, Ethel Waters: I Touched a Sparrow. Waco, Texas,

Word Books, 1978.

Young, William C. Famous Actors and Actresses on the American

Stage. New York, R. R. Bowker, 1975.

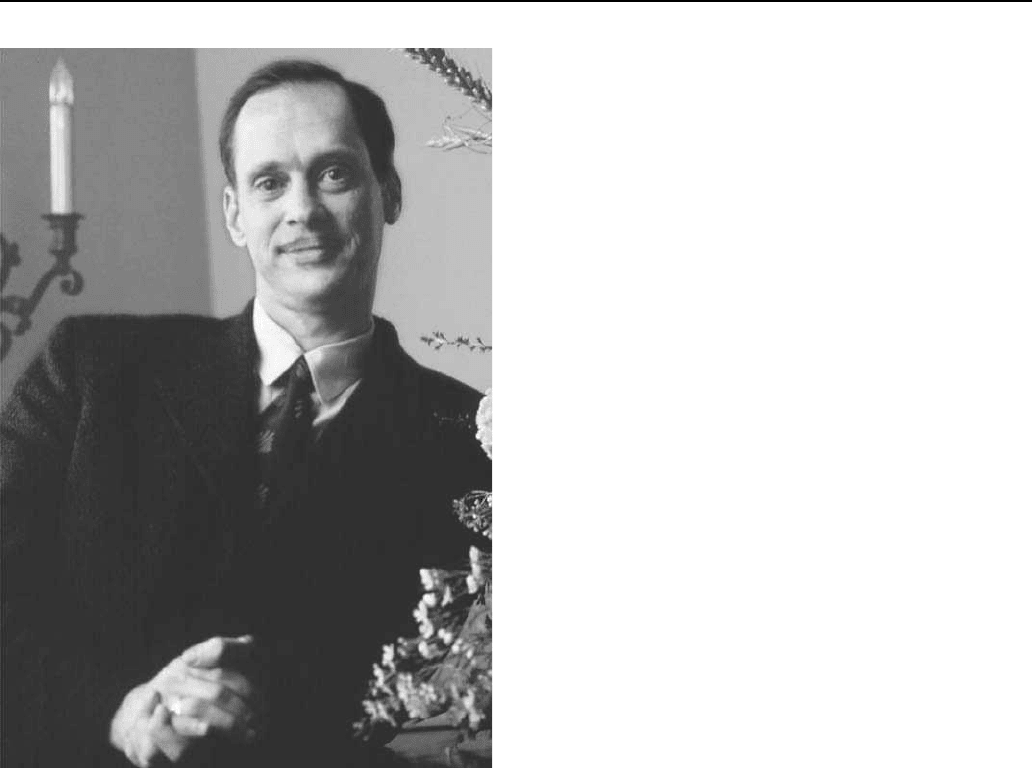

Waters, John (1946—)

Director John Waters earned the title ‘‘King of Bad Taste’’ in

1972 for Pink Flamingos, a raunchy film that makes a laughing matter

of most every type of perversion. The film ushered in a new era for

popular culture, in which the shocking and bizarre would attract

growing audiences and profits, penetrating every medium from

mainstream newspapers to day-time television talk shows. Waters

refined his obsession with ‘‘good bad taste’’—a term he coined—

over several decades, creating a new movie genre of the bizarre,

according to director David Lynch.

Waters identifies himself as a writer foremost, but he is an

example of an entrepreneur who uses many channels effectively. His

witty essays have been collected in two volumes, Shock Value (1981)

and Crackpot: The Obsessions of John Waters (1983); collections of

his screenplays and photographs also have been published. He has

made a handful of cameo appearances in films and television pro-

grams, including the voice for a cartoon character in an Emmy-

nominated episode of The Simpsons. In the 1990s, he mounted an

traveling exhibit of movie stills. A charming talk-show guest, Waters

is in demand as a speaker at college campuses, film schools,

and festivals.

The director’s opus may be grouped into two periods. Following

Pink Flamingos, his movies Female Trouble (1975), Desperate

Living (1977), and Polyester (1981) have been described as ‘‘vulgar

and cheerful nihilism,’’ ‘‘blasphemous,’’ ‘‘sophomoric,’’ and ‘‘whimsi-

cal.’’ Foul language and scatological visual and verbal references

made these works unappealing to middle America. Critics and

audiences either hated his films or loved them, hailing him as an

iconoclastic artist. His themes often presage cultural trends by dec-

ades. For example, in Female Trouble, the crazed heroine believes

death in the electric chair for a life of crime is the equivalent of an

Academy Award. Water’s loopy characterization antedated by nearly

20 years Oliver Stone’s controversial treatment of warped lovers who

go on a killing rampage to achieve media notoriety in Natural Born

Killers (1994).

In the 1990s, Waters graduated from cult and midnight-movie

houses to suburban multiplexes with such films as Hairspray (1988),

Cry-Baby (1990), Serial Mom (1994), and Pecker (1998). Waters’

second period continues his biting satire of American culture but

without reference to such perversions as incest, coprophagy, castra-

tion, necrophilia, and the gross visual images of the earlier films. A

unifying theme of both periods is his focus on characters who are

‘‘insane but believe they are sane,’’ Waters told National Public

Radio interviewer Terry Gross in 1998. His films turn normative

American values upside-down and champion outsiders.

Raised in an upper middle class family in Baltimore, Waters, like

many creative people, knew what he wanted to do early in life. He got

his first subscription to Variety at age 12 and haunted the seedier

movie theaters favoring horror films and B movies, especially admir-

ing Russ Meyers. After he was dismissed from New York Universi-

ty’s film school for smoking marijuana, he persuaded his father that

financing a series of low-budget films would be cheaper than paying

for his education. These early efforts include Hag in a Black Leather

Jacket (1964); The Diane Linkletter Story (1966), a 10-minute

exercise in bad taste about the LSD suicide of the daughter of a

famous Hollywood entertainer; Roman Candles (1966), during which

three short features are screened simultaneously on side-by-side

screens; Eat Your Make Up! (1968), satirizing the modelling industry;

Mondo Trasho (1969), a spoof of then-popular documentaries of the

bizarre and pornographic around the world; and Multiple Maniacs

WATERS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

88

John Waters

(1971), which ends with the heroine being raped by a giant lobster.

Most did not make it out of the church halls he rented for home-

town showings.

Pink Flamingos brought Waters to the attention of the avant-

garde artistic community. Andy Warhol—whose small budget films

such as Sleep convinced Waters that he, too, could make movies on a

shoestring—reportedly advised Federico Fellini to see Pink Flamin-

gos. Waters’ work has been compared to that of the Italian master.

One critic suggested that Waters had created a ‘‘Theater of Nausea,’’

comparable to Antonin Artaud’s ‘‘Theater of Cruelty’’ and Charles

Ludlam’s ‘‘Theater of the Ridiculous.’’ New York magazine hailed

Pink Flamingos as an American version of the Luis Bunuel/Salvador

Dali classic, Andalusian Dogs. Pink Flamingos was a commercial as

well as an artistic success. Made for $12,000, it earned at least

$2 million during the first few years after its release. His next

movies were made with incrementally larger budgets and found

growing audiences.

In the early films, Waters often took people on the margins of

society and transformed them into ‘‘glamorous movie stars.’’ He told

the Baltimore Sun in 1978, ‘‘To me all those outrageous-looking

people are beautiful. Because to me beauty is looks that you can never

forget.’’ It has been his life’s work to ridicule the conventions of a

society that ostracizes people who do not fit within its narrow

standards of perfection and to exploit the potential of film to bring

them the fame and success which, in his eyes, they deserve.

The greatest of his on-screen creations was the metamorphosis

of his friend Glenn Milstead into Divine, a 300-pound transvestite

who vamped it up in the skin-tight gowns of Hollywood movie

queens, with exaggerated make-up—including eyebrows that soared

up his half-shaved head—and heavily bleached and teased blond hair.

A charismatic performer, Divine took viewers by storm as the

matriarch of a family of perverted criminals vying for the title of

‘‘Filthiest Family Alive’’ in Pink Flamingos. Mink Stole, a screen

persona created for Waters’ friend Nancy Stoll, played Divine’s rival

for the title, Connie Marble. Connie and her husband Raymond (the

late David Lochary) kidnapped and impregnated young women,

chaining them in the basement of their suburban house of horrors,

then sold the babies to lesbian couples. In a scene that may never be

topped for grossness, Divine eats dog feces from the pavement to

secure the title.

Hairspray, with Divine in a supporting role, marked Waters’

transition into shopping mall theaters. The only shocking thing left for

him to do, Waters had concluded, was to make a mainstream film.

Hairspray is a light-hearted musical treatment of a serious issue—

integration. The story is based on Baltimore’s Buddy Deane Show, a

teen dance showcase that was driven off the air in 1964 by the

NAACP for segregating African-American dancers to one program a

month. In Hairspray, teenagers defeat their parents’ resistance to

integration, and everybody dances together in the film’s happy

ending. The story reflects the director’s egalitarian sentiments. He

praises Baltimore as the appropriate setting for his films because it is

an ‘‘unholy mix’’ of old money and new immigrants, black and white

poor, and a dirty industrial Eastern seaport with the Southern charm of

the first city south of the Mason-Dixon line. When it comes to night

life, Waters told Richard Gorelick, ‘‘I want to go somewhere where

everyone is mixed—that’s my ideal: rich, poor, black, white, gay, and

straight, all together.’’

With the death of the irreplaceable Divine soon after the release

of Hairspray, Waters’ transition to the mainstream was virtually

assured. Cry-Baby, an edgy Bye-Bye Birdie (1963), tells the story of a

middle-class girl who longs to ‘‘go bad’’ and her romance with the

leader of the ‘‘drapes,’’ a rock-n-rolling, motorcycle riding, black-

leather jacketed gang of juvenile delinquents. The freedom-loving

‘‘drapes’’ prevail against the repressed and repressive clean-cut

clique of upper-middle-class suburban kids. ‘‘My movies are very

moral,’’ Waters told Pat Aufderheide. ‘‘The underdogs always win.

The bitter people are punished, and people who are happy with

themselves win. They’re all about wars between two groups of

people, usually involving fashion, which signifies morals. It’s part of

a lifelong campaign against people telling you what to do with your

own business.’’

Johnny Depp as the title character with a tattooed tear-drop

under one eye guaranteed the film’s box office success. Waters turned

to star power again in his next film, featuring Kathleen Turner as

Serial Mom, a perfect suburban mother who just happens to be a serial

killer. A prolific consumer of newspapers and magazines—he sub-

scribes to over 80—Waters frequently pulls his inspiration from the

headlines. Pecker pits the innocence of a young blue-collar Baltimore

photographer who finds beauty everywhere against the exploitative

glamour of the Manhattan art world. It features rising talents Edward

Furlong, Lili Taylor, and Christina Ricci.

WATERSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

89

Waters’ success owes much to his abilities as a promoter.

Working from the trunk of his car in the early days, he persuaded East

Coast theater owners to do midnight showings of Pink Flamingos,

thus making money during hours when they normally would be

closed. Through this stroke of marketing genius, he became an

architect of the midnight cult movie showing.

Adapting his writing to yet another medium, Waters created a

photography exhibit, ‘‘Director’s Cut,’’ that toured galleries in the

1990s, using frames isolated from others’ films to author original

storyboards. This technique illustrates the cultural phenomenon that

Europeans call ‘‘bricolage,’’ the art of recycling culture to create new

works of art. Aufderheide sees the technique in Waters’ films,

commenting: ‘‘John Waters is the bard of a culture that creates itself

out of commercial trash; he’s a visionary of sorts, someone who

discovers the bizarre in the everyday and the everyday in the bizarre.’’

It is the ultimate accolade to Waters’ cultural influence that he

helped make the unspeakable acceptable, by making people laugh

about the strange and sometimes repulsive truths of everyday exist-

ence. People who were marginalized as ‘‘freaks’’ during the early

1970s now routinely appear as guests on television talk shows. Jokes

about flatulence and other bodily functions were taken up in films by

such well-known humorists as Carl Reiner and the Monty Python

troupe. In an article entitled ‘‘Mr. Bad Taste Goes Respectable,’’ U.S.

News & World Report noted that it was increasingly difficult for

Waters to retain his title when comedian Jim Carrey told ‘‘butt jokes’’

during a televised presentation of the Academy Awards.

Waters, who still lives in Baltimore and sets all of his movies

there, is a local hero because his success brought the city’s pictur-

esque locales to the attention of other film crews and made the city a

site for East Coast film making. After such Hollywood luminaries as

Alan Alda and Al Pacino arrived in town to make movies, the mayor

established the city’s Film Commission in 1980 to serve as a liaison

for movie makers seeking Baltimore locations. During the late 1960s

and early 1970s, the group of self-styled ‘‘juvenile delinquents’’ and

eccentrics that Waters gathered around himself evolved into Dreamland

Studio, an ensemble production company. Waters was still working

with many of the same people in front of the camera and behind the

scenes by the end of the 1990s. Reconciled with his family after years

of rebellion, a proud home owner who holds backyard barbecues for

the Dreamland survivors, Waters told Aufderheide, ‘‘It’s hilarious

that in some ways I’ve become part of the establishment.’’

To his credit, Waters has never tried to top the vulgarity of Pink

Flamingos, instead honing his talent to mock social intolerance,

transvalue society’s standards, and take every bizarre reality to its

extreme. Long before radio ‘‘Shock Jock’’ Howard Stern came along,

John Waters was simultaneously offending people and making

them laugh.

—E. M. I. Sefcovic

F

URTHER READING:

Aufderheide, Pat. ‘‘The Domestication of John Waters.’’ American

Film. Vol. 15, No. 7, April, 1990, 32-37.

Geier, Thom. ‘‘Mr. Bad Taste Goes Respectable.’’ U. S. News &

World Report. April 28, 1997, 16.

Gorelick, Richard. ‘‘John Waters’ ‘Pecker’ Is His Gayest Film Ever,

Mary.’’ Gay Life (Baltimore). September 4, 1998, B6-B7.

Hirschey, Geri. ‘‘Waters Breaks.’’ Vanity Fair. March, 1990, 204-

208, 245.

Hunter, Stephen. ‘‘A Good Place to Raise a Movie.’’ Washington

Post. September 27, 1998, G1, G6.

Mandelbaum, Paul. ‘‘Kink Meister.’’ New York Times Magazine.

April 7, 1991, 34-36, 52.

Sefcovic, Enid. ‘‘Smutty Waters Just Keeps Rolling Along.’’ Extra.

April 20, 1975, 6, 10.

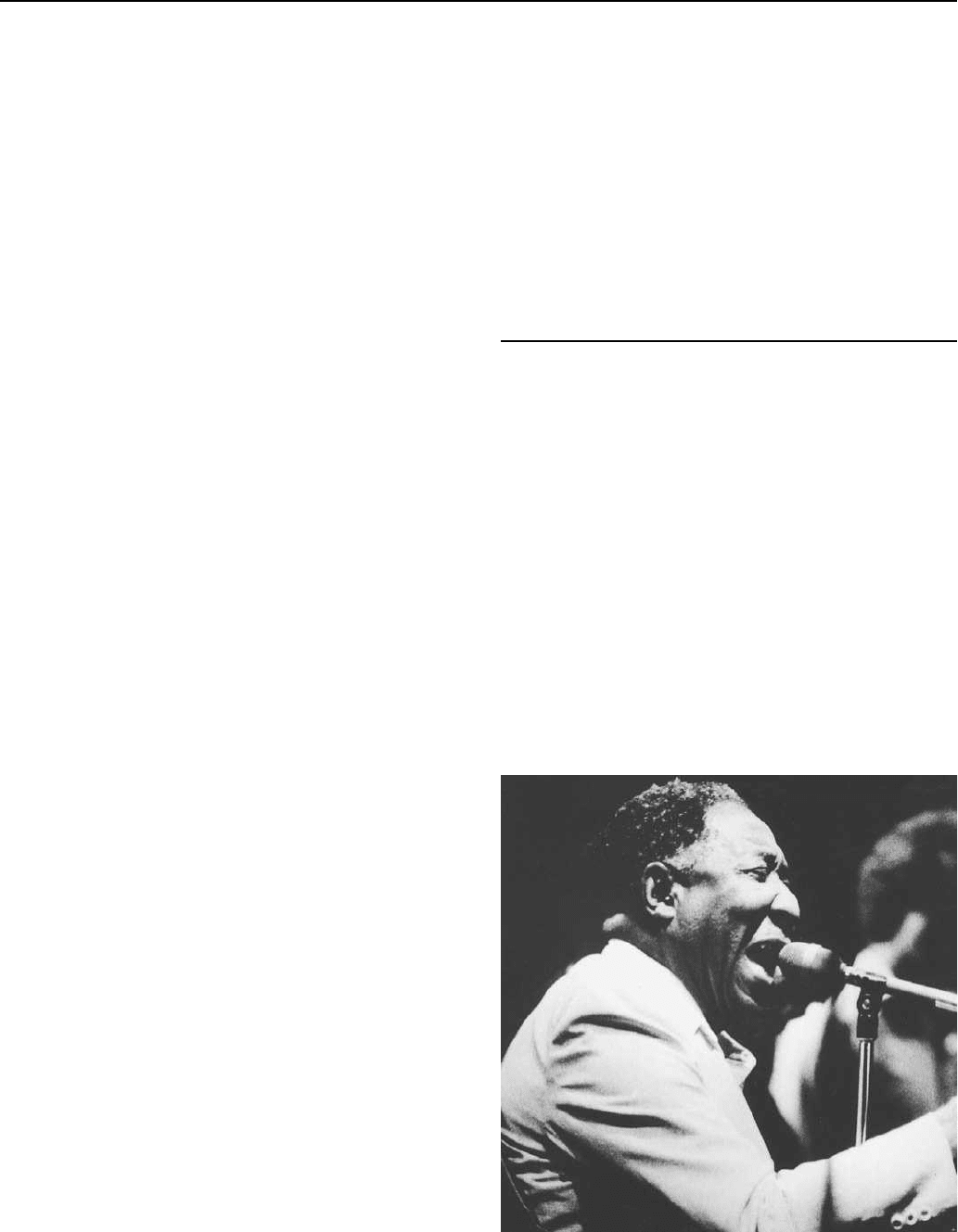

Waters, Muddy (1915-1983)

Muddy Waters’ affirmation, in the title of his composition ‘‘The

Blues Had a Baby and They Called It Rock and Roll,’’ is somewhat

autobiographical, striking both at home and abroad. For rock ’n’ roll,

Waters was a mentor whose musical style was widely emulated,

directly linking the blues to rock ’n’ roll; he was the musical father of

post-war Chicago blues.

Born McKinley Morganfield, the vocalist, guitarist, and songwriter

played a major role in the evolution of rock ’n’ roll, influencing scores

of rock and blues musicians such as Mick Jagger, the Beatles, Mike

Bloomfield, Paul Butterfield, Bob Dylan, James Cotton, and Johnny

Winter. His 1950 composition, ‘‘Rolling Stone,’’ inspired the name

for Jagger’s rock group. In 1949, Waters transformed the ‘‘down-

home’’ country Mississippi Delta style to an urbanized raw and

uncompromising Chicago style blues. His band attracted some of the

finest Chicago musicians, many of whom later formed their own

bands. Waters’ impact on the conventional blues aesthetic, Chicago

blues, and rock ’n’ roll music is unparalleled.

Muddy Waters

WATSON ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

90

The basis for Waters’ Chicago style was centered in the Missis-

sippi Delta. He was born on April 4, 1915 in Rolling Fork, Mississip-

pi. His father was a farmer and part-time musician. When his mother

died, Waters moved to Clarksdale to live with his grandmother. His

early musical experiences consisted of singing in the church choir and

playing blues in juke joints and at suppers, picnics, and parties. When

Waters was nine, his father taught him to play the harmonica and the

guitar—he otherwise was largely self-taught. He earned the world-

famous nickname Muddy Waters by often performing ‘‘in the dirt’’ in

and around the Delta.

Black patrons’ taste for the blues in the juke joints in the

Mississippi Delta changed when they moved to Chicago. Likewise,

when Waters decided to move to Chicago in 1943, he made changes

in his music to appeal to this changing musical taste. The music

became louder, with amplified instruments, more forceful rhythms,

and the accompaniment now enhanced by five musicians. Before

starting his own band, Waters was a sideman with John Lee ‘‘Sonny

Boy’’ Williamson at the Plantation Club.

It was as a sideman for Sunnyland Slim that Waters got his first

commercial recording break. Alan Lomax had initially recorded

Waters in 1941 for the Library of Congress’s archives on the Stovall

plantation in Mississippi. In 1948, at the end of a recording session in

the Aristocrat (later Chess) recording studio, some free time was

allotted to Waters and he recorded his first single, ‘‘Gypsy Woman.’’

The record was successful enough to provide an opportunity for

another recording session. Subsequent recordings of ‘‘(I Feel Like)

Going Home,’’ ‘‘Rollin’ Stone,’’ ‘‘I Can’t Be Satisfied,’’ and ‘‘Man-

nish Boy’’ established the archetype for the post-war Chicago

blues style.

While various musicians worked for him over the years, Waters

in 1953 assembled one of the best-ever Chicago blues bands consist-

ing of harmonica player Little Walter Jacobs, pianist Otis Spann,

guitarist Jimmy Rodgers, and drummer Elgin Evans. With various

personnel, Waters’ band toured the South, the rest of the United

States, and eventually Europe. Willie Dixon, a celebrated singer,

bassist, and composer in his own right, wrote a number of songs

specifically for Waters that were successful, including ‘‘Hoochie

Coochie Man’’ and ‘‘Same Thing.’’ By 1958, Waters had scored 14

hits in the top ten rhythm and blues charts. In the same year, he toured

with Otis Spann in the United Kingdom; reviews were mixed because

the British audience’s perception of the blues was misguided, having

been accustomed to the acoustic performances of artists such as Big

Bill Broonzy and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

Waters’ vocal approach drew from the congregational song style

of the black church. He often moaned (hummed) the ends of phrases.

He also made extensive use of a recitative style, bending and sliding

upward on syllables with shouts, vocal punches, and occasional use of

the upper falsetto register. His guitar style made extensive use of the

slide or bottleneck technique, the use of repetitive guitar phrases in

response to his vocal line in typical call and response fashion, and an

uncompromising rough musical texture.

As soul music gained favor among blacks in the 1960s, there was

a decreasing interest in the blues. Waters’ popularity among black

patrons consequently began to wane. Fortunately, the blues revival

was taking place in the United States and United Kingdom, and

musicians were emulating American blues. As groups began to

acknowledge Waters’ influence, renewed attention to his music

occurred. This, along with his performance and recording at the 1960

Newport Jazz Festival, and Johnny Winter serving as producer for

several successful collaborations with Waters in the 1970s, fueled a

rediscovery of his music by a largely white audience. Waters was at

the center of a revival of interest in the blues and the genre’s

influence on rock.

Waters continued to hit his artistic stride, gaining financial

success. His band won the Downbeat Critics Poll for rhythm and

blues group in 1968, and a Grammy for Best Ethnic/Traditional

recording—They Call Me Muddy Waters—in 1971. In an interview,

Waters defined the music he played as follows: ‘‘I think it’s about

tellin’ a beautiful story . . . something about the hard times you’ve

had.’’ Waters died quietly in his sleep at his home in the Chicago

suburb of Westmont on April 30, 1983.

—Willie Collins

F

URTHER READING:

Rooney, James. Bossmen: Bill Monroe & Muddy Waters. New York,

Dial Press, 1971.

Watson, Tom (1949—)

Dominating golf in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Tom Watson

is one of the greatest golfers of modern times. Watson is second only

to Harry Vardon in British Open Championships with five wins.

Performances overseas led to his immense popularity with citizens of

the British Isles. His two Masters, along with his dramatic victory in

the 1982 United States Open at Pebble Beach give him a total of 8

major championship victories. His fiery duels with Jack Nicklaus in

the late 1970s made for excellent television, and in this, Watson

contributed to the spread and popularity of golf. Watson was named

Player of the Year for four consecutive years, and won the Vardon

trophy for lowest scoring average three times.

—Jay Parrent

F

URTHER READING:

Feinstein, John. A Good Walk Spoiled. Boston, Little, Brown and

Company, 1995.

Peper, George, editor, with Robin McMillan and James A. Frank.

Golf in America: The First One Hundred Years. New York, Harry

N. Abrams, 1988.

The Wayans Family

Continuing to make strong contributions to the American come-

dy scene, the Wayans family has been one of the most successful and