Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 5: U-Z

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WALTERSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

71

welcomed the new neighbor, finding that their own business commu-

nity has prospered from the increased consumer traffic. But much

more commonly, local communities perceive the giant store on the

edge of town as a threat to main street merchants unable to compete

with the bulk purchasing power of a national chain that prides itself on

passing its savings on to the consumer. Charges of unfair labor

practices have not fazed the infamously non-union shop. For all its

self-congratulatory stance on promoting ecology issues and being

green, the company has also been criticized for its use of veiled threats

and other heavy-handed tactics in dealing with local zoning laws and

environmental regulations. On-going opposition by local communi-

ties to Wal-Mart’s expansion plans will most likely continue. There

may come a time when the company feels it has largely saturated the

market for its discount retailing operation. Increasing popularity of

electronic catalogs and Internet-based shopping may begin to dent the

fortunes of this giant, but so far there appears no sign of slowing

down, and for now anyway, that big Wal-Mart store is here to stay.

—Robert Kuhlken

F

URTHER READING:

Graff, Thomas, and Dub Ashton. ‘‘Spatial Diffusion of Wal-Mart:

Contagious and Reverse Hierarchical Elements.’’ Professional

Geographer. Vol.46, No. 1, 1994, 19-29.

McInerney, Francis, and Sean White. The Total Quality Corporation.

New York, Truman Talley Books, 1995.

Ortega, Bob. In Sam We Trust: The Untold Story of Sam Walton and

How Wal-Mart Is Devouring America. Times Books, 1998.

Schneider, Mary Jo. ‘‘The Wal-Mart Annual Meeting: From Small-

town America to a Global Corporate Culture.’’ Human Organiza-

tion. Vol.57, No. 3, 1998, 292-299.

Trimble, Vance. Sam Walton: The Inside Story of America’s Richest

Man. New York, Dutton, 1990.

Vance, Sandra, and Roy Scott. Wal-Mart: A History of Sam Walton’s

Retail Phenomenon. New York, Twayne Publishers, 1994.

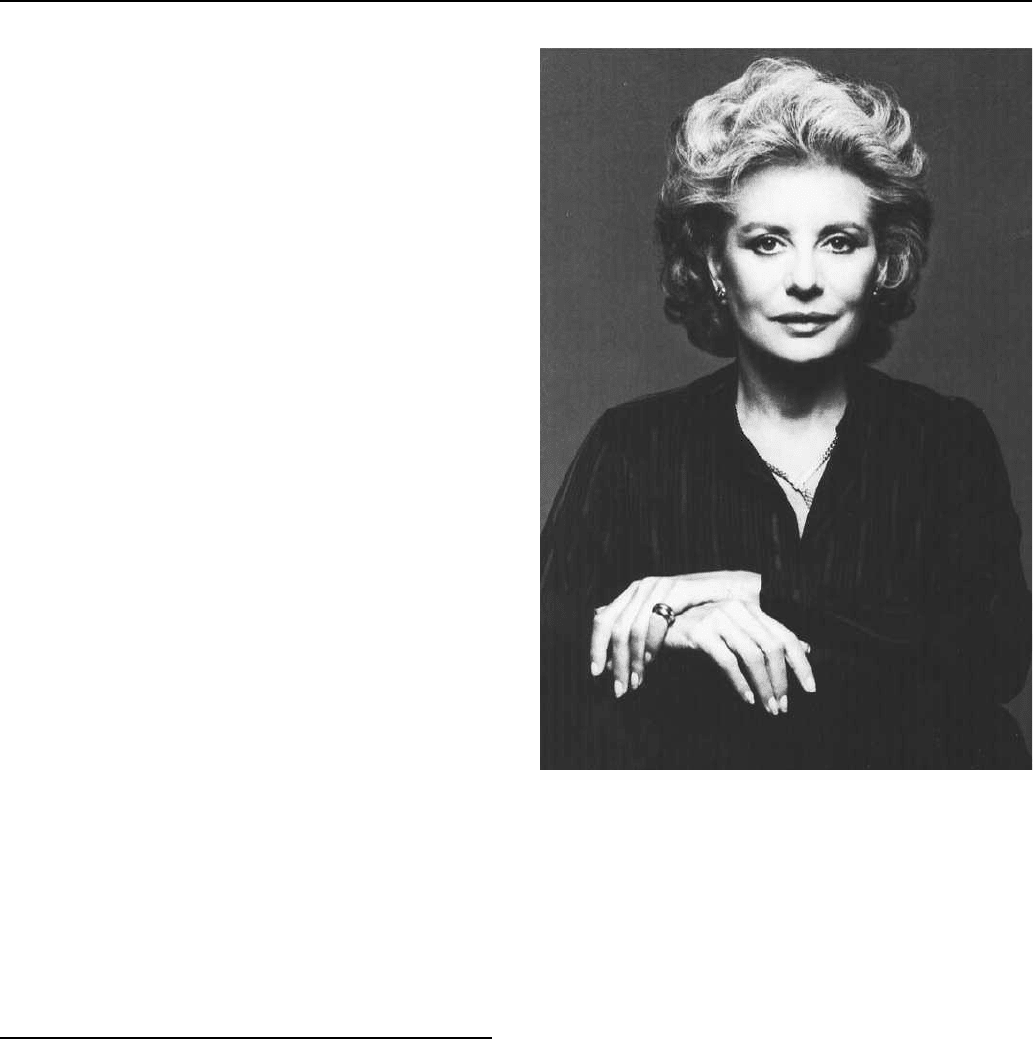

Walters, Barbara (1931—)

About her career as a television newswoman and interviewer,

first lady of the news Barbara Walters has said, ‘‘I was the kind

nobody thought could make it. I had a funny Boston accent. I couldn’t

pronounce my Rs. I wasn’t a beauty.’’ Walters did make it, even in the

often superficial, looks-obsessed world of network television. Partial-

ly as a result of attempting to make it at the right time in history—the

feminist movement of the early 1970s was gaining strength—Walters

not only made a place for herself in television news, but also changed

the way the news was presented on television.

Barbara Walters was born, however unwillingly, into show

business. Her father, Lou, was a nightclub owner who ran the Latin

Quarter, a chain of popular clubs in New York, Boston, and Florida.

Though celebrities were a part of her everyday life growing up, the

Barbara Walters

girl who was to become a nightly visitor in the homes of millions of

Americans wanted nothing more than to be ‘‘normal.’’ But that was

denied her when her father suddenly went bankrupt and suffered a

heart attack. In her yearbook from Sarah Lawrence College, Walters

is pictured in a cartoon as an ostrich with its head stuck in the sand, but

she was forced to face the world early. To help her parents and

developmentally disabled sister out of their financial troubles, she

went to work, first as a secretary, then as a writer on such television

shows as Jack Paar and The Dick Van Dyke Show. In 1961, she got a

job as a writer/researcher for the Today Show, and in 1964 she moved

in front of the camera when she was promoted to ‘‘Today girl,’’ a title

reflecting the sexist atmosphere prevailing in television at the time.

But sexism notwithstanding, Walters was on her way to being a

serious television journalist. In 1972, when President Nixon changed

U.S. policy and paid an official visit to the People’s Republic of China

for the first time since their revolution, Barbara Walters was the only

woman to cover that trip.

She continued to make history and created a buzz of controversy

in 1976 when ABC signed her to a five-year contract for $1 million

per year. She was given the job of co-anchor on the nightly news,

sitting at the desk with longtime television news man Harry Reasoner.

The industry and the country were shocked at the idea of a woman

receiving so much money—twice the salary of venerable CBS news

WALTON ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

72

legend Walter Cronkite. When Walters went to work as the first

woman to anchor the evening news, she encountered ridicule, dismissive

attitudes, and outright hostility. Reasoner himself was not happy to be

working with her and let it show. Time magazine dubbed Walters the

‘‘Most Appalling Argument for Feminism.’’ Even when she proved

her journalistic skills by hosting the first joint interview with Presi-

dent Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Prime Minister Menachem Begin of

Israel, viewers just did not seem to respond to her. The flagging ABC

news ratings did not rise, and Walters was removed from the news

desk in 1979 and given a new job—correspondent on the news

magazine show 20/20.

Walters soon rose to co-host 20/20 with Hugh Downs, and the

show expanded from Friday nights to air editions on Wednesday and

Sunday nights as well. Sunday nights she co-hosted with Diane

Sawyer, another pioneering woman television journalist. In an indus-

try that is more likely to capitalize on competition among women for

high-visibility positions, the pairing of the two female anchors was

unusual and refreshing.

Though her credentials as a newswoman are impressive, it is as

an interviewer that Walters will be remembered. She has created more

than sixty ‘‘Barbara Walters Specials’’ and ‘‘Most Fascinating Peo-

ple’’ shows, which aired at prime audience-grabbing times, such as

following the Academy Awards show and on New Year’s Eve. In

each special she interviews several celebrities and over the years has

delved into the personal lives of political figures, timeless icons of

entertainment, and ‘‘flashes in the pan.’’ Her interviews have become

such a television standard that it is not clear whether Barbara Walters

interviews those who have ‘‘made it,’’ or whether one has not really

‘‘made it’’ until one has been interviewed by Walters. The interviews

are incisive and revealing. Bill Geddie, producer of the Walters

specials, says of her, ‘‘She has a way that has matured over the years

of getting people to say things on the air that they never thought they

were going to say.’’ Walters herself attributes much of her success as

an interviewer to her devotion to her disabled sister, Jacqueline.

Growing up so close to the difficulties her sister faced gave her an

empathy and compassion she was able to use throughout her career.

In 1997, Walters branched out into another television standard—

the talk show. Following her introduction ‘‘I’ve always wanted to do

a show with women who have very different views. . . ’’ The View

introduced a new format—the multi-host talk show. Co-hosts journal-

ist Meredith Viera, lawyer Star Jones, comic Joy Behar, and model

Debbie Matenopoulos are occasionally joined by Walters for the

usual talk show fare: a few celebrities, a few writers of self-help

books, and some lightweight chat about current newsmaking events.

The View is advertised by Walters as ‘‘Four women, lots of opinions,

and me—Barbara Walters.’’ Though one suspects that Walters’s

separation of herself from the ‘‘four women’’ is not accidental, on

The View she is looser and more relaxed—called ‘‘B.W.’’ by her

colleagues and allowing herself to be teased and, occasionally, put on

the spot.

Walters’s distinctive style has often been parodied with a

ruthlessness that indicates what an icon she herself has become.

Probably the most famous send-up was performed by the late Gilda

Radner on the early Saturday Night Live show. With stiffly flipped

hair and exaggerated lisp, Radner’s ‘‘Barbara Wawa’’ became almost

as familiar to viewers as Walters herself. Later SNL crews also have

parodied Walters’s The View. Though hurt by the mockery at first,

Walters soon learned that it was a measure of her own popularity, and

she even invited the SNL cast to perform their parody on an April

Fool’s edition of The View.

While satire is a tribute on one hand, Walters does have her

critics. She has been called aggressive and overbearing, common

criticisms of women successful in male-dominated businesses, and

some have questioned her tactics for getting interviews. Many have

criticized her for confusing news and entertainment. A standing joke

in the industry revolves around her ‘‘touchy-feely’’ interviewing

style, falsely attributing to her the question ‘‘If you were a tree, what

kind of tree would you be?’’ In 1981, during an interview with actress

Katharine Hepburn, Hepburn herself stated that at that point in her life

she felt like a tree. Following her thought, Walters asked, ‘‘What kind

of tree are you?’’ Hepburn responded that she felt like an oak, and the

question moved forever into the archive of jokes about Walters.

Barbara Walters will be remembered for many ‘‘firsts’’ and

‘‘onlys.’’ Her critics blame her for bringing too much entertainment

into the news, but, for better or worse, she has been pivotal in creating

the face of television news in the 1990s, a blend of fact, entertainment,

and personality. There is no doubt that every woman in television

news owes a debt to the girl whose college yearbook pictured her as an

ostrich but who could not keep her head in the sand. Walters does not

glamorize herself or her contributions, ‘‘I was frustrated and tena-

cious,’’ she says, ‘‘and that’s a powerful combination.’’

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Fox, Mary Virginia. Barbara Walters: The News Her Way. Minne-

apolis, Dillon Press, 1980.

Malone, Mary. Barbara Walters: TV Superstar. Hillside, New Jersey,

Enslow Publishers, 1990.

Oppenheimer, Jerry. Barbara Walters, An Unauthorized Biography.

New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

Remstein, Henna. Barbara Walters. Philadelphia, Chelsea House, 1999.

Walton, Bill (1952—)

Despite an injury-plagued career, in his brief peak Bill Walton

was compared with some of the greatest centers in National Basket-

ball Association (NBA) history. In addition to his on-court contribu-

tions, which include leading the Portland Trailblazers to an NBA

Championship in 1977 and serving as a key reserve during the Boston

Celtics’ 1986 Championship season, Walton’s outspoken political

views and colorful personal life have kept him in the spotlight.

Walton began his career playing for the University of California

at Los Angeles (UCLA) in the early 1970s, where he won three

consecutive College Player of the Year Awards. In the 1973 National

Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Championship game against

Memphis State, Walton hit an unbelievable 21 out of 22 shots. During

WALTONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

73

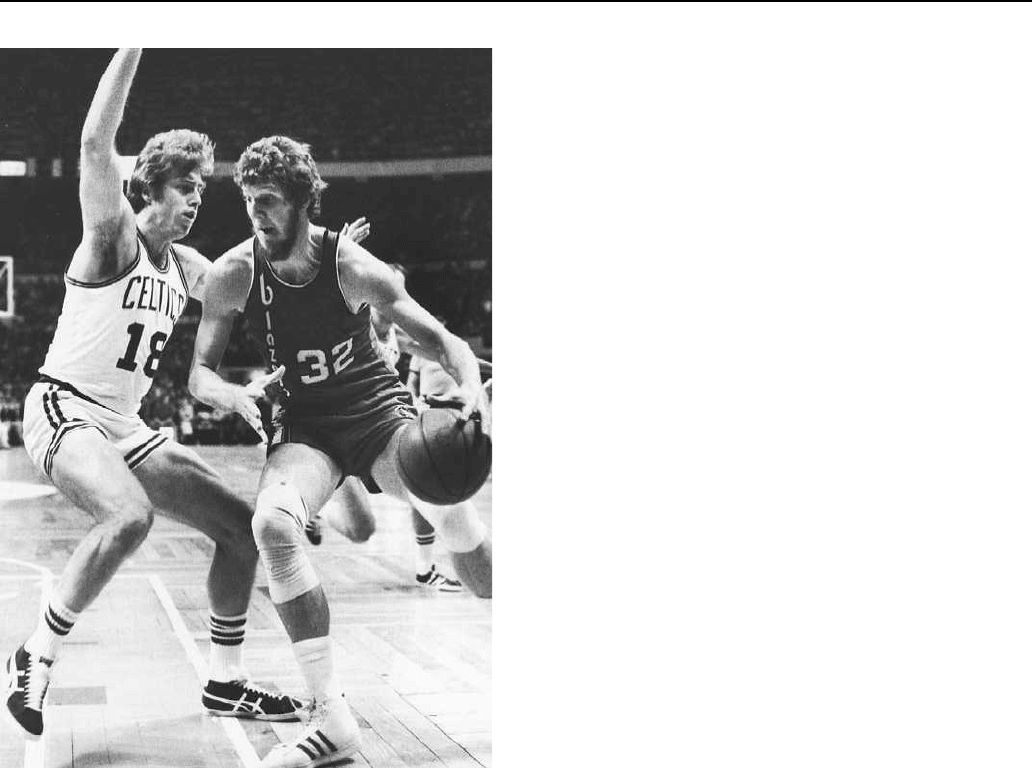

The Trailblazers’ Bill Walton (right) drives against the Celtics’

Dave Cowens.

Walton’s career, UCLA won 86 of 90 games and two national

championships, one in 1972 and another in 1973. For his career,

Walton holds the record for highest field goal percentage in NCAA

tournament play, having hit almost 69 percent of the shots he

attempted between 1972 and 1974.

While his play on the court was outstanding during his college

career, Walton also began to attract attention for his political views at

UCLA. He was arrested during his junior year at an anti-Vietnam War

rally, and issued a public statement criticizing President Richard

Nixon and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Walton was also an

avid fan of the rock group the Grateful Dead, frequently attending

their concerts.

Although Walton’s long history of injuries had already reared its

head during his high school and college careers—he suffered a broken

ankle and leg and underwent knee surgery while playing at Helix

High School in La Mesa, California—he was nonetheless chosen as

the first player in the 1974 NBA draft by the Portland Trailblazers.

While Walton played impressively during his first two seasons,

injuries limited him to approximately half of the possible games he

could have played in during that time.

It was during the 1976-1977 season, however, that Walton really

came into his own, scoring nearly 19 points per game and leading the

league in rebounding and blocked shots. The Trailblazers reached the

NBA Finals against Philadelphia that season, but lost the first two

games of the best-of-seven series, a situation which only one team in

NBA history had overcome. Largely due to Walton’s spectacular

play, however, the Blazers won the next four games, capturing the

NBA Championship in six games. Walton was named the Most

Valuable Player (MVP) of the series, setting NBA finals single-game

records for defensive rebounds and blocked shots.

The following season, 1977-1978, Walton played even more

impressively, earning the league’s MVP award as the Blazers won 50

of their first 60 games. Injuries, however, kept him out of the final 24

regular season games. Walton attempted to come back in the playoffs,

but it was discovered that the navicular bone in his left foot was

broken. Without Walton, the Blazers lost in the playoffs to the

Seattle Supersonics.

Walton was traded to the then-San Diego Clippers following the

1977-1978 season, after an extremely acrimonious parting with the

Trailblazers, whom he accused of providing him with poor medical

advice. Walton missed most of his first two seasons with the Clippers,

drawing criticism from his teammates and fans, who felt the team had

erred in signing Walton to a lucrative long-term contract. Although

Walton’s health improved and he was able to play fairly extensively

in the 1983-1984 and 1984-1985 seasons, the Clippers never rose

above mediocrity, and Walton never had the chance to repeat his

playoff successes with Portland.

After his contract with the Clippers ran out, Walton contacted

several of the League’s top teams, seeking to find out if they needed a

reserve center. Fortunately for Walton, the Boston Celtics, a champi-

onship contender, needed a quality big man of Walton’s caliber to

provide them with greater depth. Walton joined the team for the 1985-

1986 season. The pickup paid incredible dividends for the Celtics, as

Walton played in all but two of the team’s 82 regular season games

and every playoff game. While Walton’s numbers were modest, he

made a major contribution to the team’s 67-15 record, as he provided

scoring, rebounding, passing, defense, and high energy during his

time on the court. Walton received the league’s Sixth Man Award,

given to the top reserve player in the league. The Celtics, with Walton

backing up frontcourt legends Kevin McHale and Robert Parish,

breezed through the playoffs that season, defeating the Houston

Rockets in six games. The following season, however, injuries

limited Walton to only 10 games, after which he retired.

Walton became a television announcer in 1991 for the National

Broadcasting Network (NBC), and has served as an analyst for

basketball, volleyball, and other sports. He was named to the Naismith

Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1993, and in 1996 was named

one of the 50 greatest players in NBA history. Walton, who studied

law at Stanford University during his breaks from basketball, lives

with his four sons in San Diego.

—Jason George

F

URTHER READING:

Halberstam, David. The Breaks of the Game. New York, Alfred A.

Knopf, 1981.

‘‘NBA History: Bill Walton.’’ http://www.nba.com/history/

waltonbio.html. June 1999.

WALTONS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

74

‘‘NBA on NBC Broadcasters: Bill Walton.’’ http://

www.nba.com/ontheair/00421666.html. June 1999.

The Waltons

From 1972 to 1981, the Depression Era returned to America

through the popular television series, The Waltons. For nearly a

decade, American viewers embraced The Waltons into popular cul-

ture as a symbol of past family values that were largely absent in

American television programs.

Earl Hamner, Jr., creator of The Waltons, grew up an aspiring

writer in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Schuyler, Virginia. His early

novel, The Homecoming, was a literary recollection of his own

Depression Era childhood, of which he speaks fondly: ‘‘We were in a

depression, but we weren’t depressed. We were poor, but nobody ever

bothered to tell us that. To a skinny, awkward, red headed kid who

secretly yearned to be a writer . . . each of those days seemed filled

with wonder.’’ In 1970, Lorimar Productions approached Hamner to

create a one-hour television special based on The Homecoming, and

hence, the Walton family made its television debut. Against the

advice of reviewers and network executives who had little faith in the

appeal of family programming, CBS took a chance and placed The

Waltons in a Thursday night prime-time slot. To the surprise of many,

the series not only held its own, but maintained a number eight

position in the ratings for years to follow.

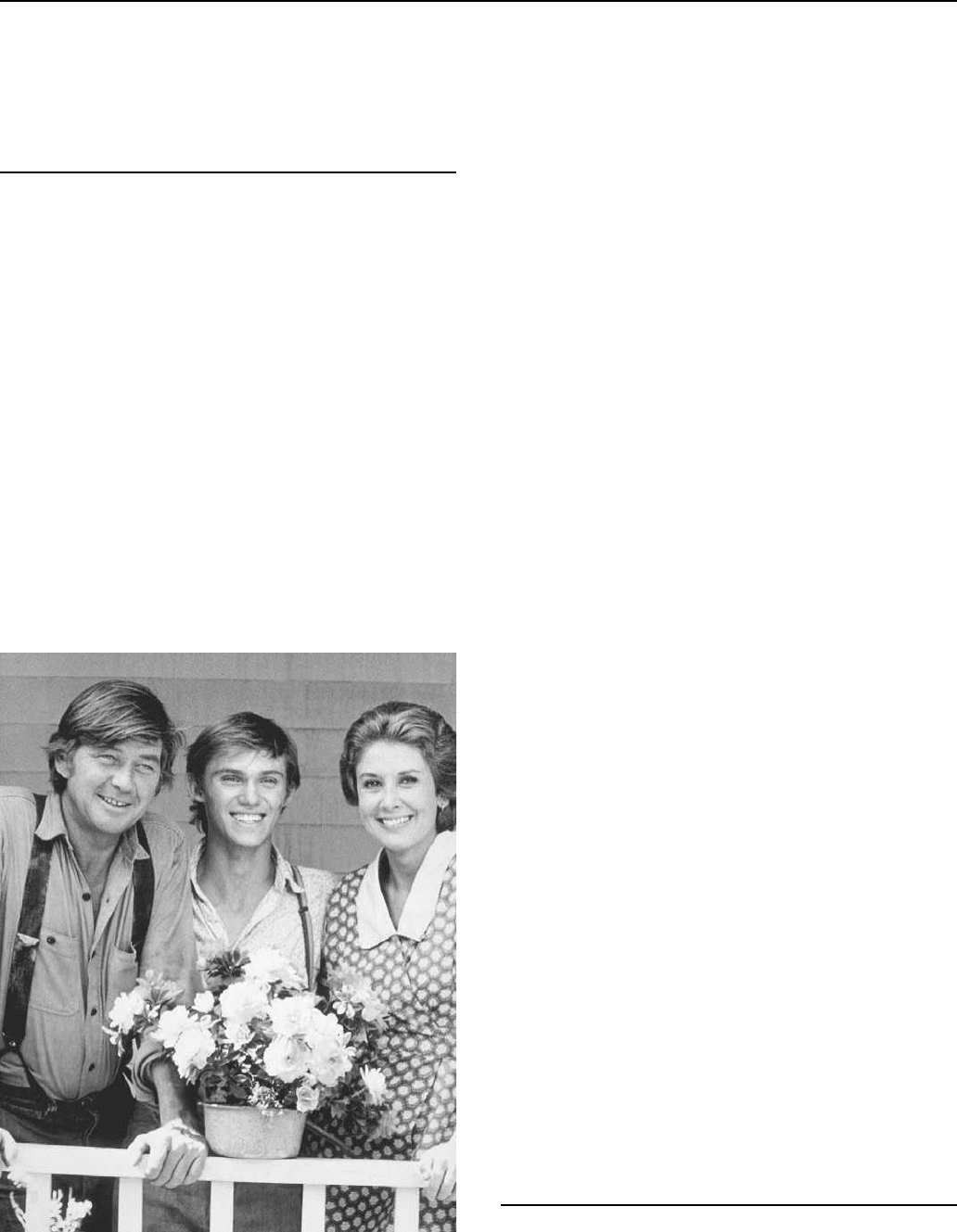

(Left to right) Ralph Waite, Richard Thomas, and Michael Learned.

For viewers concerned with the growing number of television

shows whose content often included violence or sexually oriented

themes, the Walton family offered a refreshing option. Representative

of Hamner’s own family, members of the large Walton clan were

richly endowed with a common thread of love, pride, and responsi-

bility, yet each uniquely contributed to the depiction of rural America

from the Depression era to World War II. This ideal family was

headed by proud patriarch and millwright John Sr. (Ralph Waite), his

wife, Olivia, a loving and devout Christian mother (Michael Learned),

and the prolific writer and boy-next-door, John-Boy (Richard Tho-

mas). There was Mary-Ellen, the headstrong nurse (Judy Norton), the

musically talented Ben (Jon Walmsley), the lovely Erin (Mary

McDonough), and Ben, the budding entrepreneur (Eric Scott). Along

with these eight were aspiring aviator Jim Bob (David W. Harper),

Elizabeth (Kami Cotler), the youngest Walton, and the grandpar-

ents—Grandpa Zeb, the beloved woodsman (Will Geer), and tena-

cious Grandma Ester (Ellen Corby). Added to this numerous collec-

tion of distinctive individuals was a large cast of vibrantly colorful

and richly developed supporting characters.

While critics of The Waltons have accused the show of being

‘‘sugarcoated’’ and unrealistic, a glance at some of the thematic

content might prove otherwise. Among the issues and events that

were dealt with in the series were rural poverty, bigotry, the Hindenburg

disaster, the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the death of a family member,

draft evasion and, of course, the human cost of war. Richard Thomas,

reflecting on this popular misconception in a 1995 interview said,

‘‘One of the common errors in describing the show is that it was all so

nice, everyone was nice. It’s just not true. Everyone in the show could

be foolish, everyone was hotheaded. John-Boy was always confront-

ing people . . . It was not this very sweet little family.’’

The family’s unifying force, however, and perhaps the focal

point of the show’s broad demographic appeal, was that family

members always maintained a high level of respect for one other,

finding genuine joy in living while nevertheless working out the

internal and external conflicts that defined their daily lives on

Walton’s Mountain. Perhaps, too, The Waltons fulfilled a desire in

post-1960s America to return to a simpler time when families still ate

supper together at the kitchen table, the General Merchandise was the

social and economic hub of a community, and, at the end of a hard but

honest day, familiar voices in the darkness of a white clapboard

farmhouse could be heard to say, ‘‘Good night, John-Boy.’’

—Nadine-Rae Leavell

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘The Waltons Home Page.’’ http://www.the-waltons.com. April 1999.

Hamner, Earl Jr. The Homecoming. New York, Random House, 1970.

Keets, Heather. ‘‘Good Night, Waltons.’’ Entertainment Weekly.

August 20, 1993, 76.

War Bonds

War bonds are a method of financing war that reduces demand

for goods and services by taking money out of circulation through

WAR MOVIESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

75

A War Bonds poster.

investment in the bonds. This provides funds to underwrite the war.

Modern warfare is an expensive business and must be financed

carefully, else a government risks triggering inflation by increasing

demand for goods. One method of avoiding this outcome is to raise

taxes to finance the war, but such methods risk making a war

unpopular. Through the more popular method of selling war bonds,

citizens, in effect, invest in the war effort of their government just as

they might invest in stocks. Selling war bonds lessens the need for

tax increases.

During World War I, the U.S. government raised $5 billion

through the sale of Liberty Bonds. Mass rallies to sell the bonds

featured celebrities such as Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. Nonetheless,

when most Americans talk about war bonds they are generally

referring to the bonds sold during World War II. In part this is because

the efforts of World War I involved a good deal of compulsion rather

than persuasion. During that war school children were badgered,

courts imposed illegal fines on those not owning bonds, and the

houses of non-purchasers were painted yellow. But World War II

bonds are probably better remembered simply because, by then, mass

media had expanded considerably and the scale of the media cam-

paign was greater.

War bonds were but one of the means at the government’s

disposal to regulate the wartime economy. During World War II, the

cost of living in the United States increased by about thirty-three

percent. Most of this increase occurred before 1943, when the

government put strict price controls in place through the Office of

Price Administration. The Revenue Act of 1942 established the

modern American tax structure, which saw the tax base increase four-

fold and introduced tax withholding. Through these measures, the

government raised about fifty percent of its costs during the war. This

was a considerable accomplishment compared to the thirty percent

raised during World War I and twenty-three percent during the Civil

War. During World War II, war bonds raised approximately $150

billion, or a quarter of the government’s costs.

According to historian John Blum, the Secretary of the Treasury,

Henry Morgenthau, said he wanted ‘‘to use bonds to sell the war,

rather than vice versa.’’ Morgenthau believed that there were quicker

and easier ways for the government to raise money than through bond

issues, but that it would increase people’s stake in the war effort if

they bought bonds. Many businesses promoted war bond purchases.

Entertainment industry figures lent their celebrity to bond drives.

Singer Kate Smith sold $40 million worth of bonds in a sixteen-hour

radio session on September 21, 1943. Hollywood starlet Loretta

Young sold bonds at a Kiwanis meeting and pin-up girl Betty Grable

auctioned off her stockings. Comic book publishers DC and Marvel

carried advertisements and columns urging their readers to tell their

parents to buy bonds and to purchase 10-cent defense stamps them-

selves. Covers of Batman and Superman comics appealed to readers

to buy war bonds to ‘‘Keep Those Bullets Flying’’ and ‘‘Slap a Jap.’’

War bonds were a relatively effective measure in reducing

inflation and financing the war. Moreover they served as a means of

popularizing the war by giving non-combatants a direct stake in its

outcome. As sound fiscal policy, the measure of their worth can be

judged by the inflationary pressures unleashed by President Lyndon

Johnson’s decision to finance the Vietnam War, which cost $150

billion, by printing more money rather than raising taxes or

selling bonds.

—Ian Gordon

F

URTHER READING:

Blum, John Morton. V Was for Victory: Politics and American

Culture During World War II. New York, Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich, 1976.

Perrett, Geoffrey. Days of Sadness, Years of Triumph: The American

People, 1939-1945. Baltimore, Penguin, 1973.

Polenberg, Richard. War and Society: The United States, 1941-1945.

New York, J. B. Lippincott, 1972.

War Movies

As long as films have been made, war movies have been a

significant genre, with thousands of documentaries, propaganda

films, comedies, satires, or dramas reminding moviegoers of the deep

human emotion and violence of the combat experience. Throughout

the twentieth century, war movies have both reflected and manipulat-

ed changing popular attitudes toward war. Some of the films, espe-

cially those created during wartime, were created as propaganda,

showing the patriotism and heroism of soldiers and the glory attained

WAR MOVIES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

76

Troops storm the beach in a scene from the film The Longest Day.

in battle. Still others take on the subject of war only to criticize it,

usually via a graphic depiction of the cost of war in terms of

human lives.

War has interested filmmakers from the first days of cinematic

technology. J. Stuart Blackton’s 1898 film, ‘‘Tearing Down the

Spanish Flag,’’ is considered not only the first fictional American war

movie, but also the first propaganda film. Set on an anonymous

rooftop in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, this short film

depicts a uniformed American soldier (played by Blackton himself)

removing the Spanish flag and replacing it with an American one,

then cuts to a title card stating, ‘‘Remember the Maine.’’ Blackton’s

film was quickly followed by reenactments of the sinking of the

Maine and other battles of the Spanish-American War. Even though

the film is only a few minutes long, it managed to capture the

contemporary popular imagination and established the foundation for

war movies in the twentieth century.

Most American films made during World War I consisted of

propaganda films either encouraging or, after 1917, supporting Ameri-

can involvement in the European conflict. Most of these films

romanticized the war, showing enlistment as a glorious, patriotic duty

and emphasizing the power and importance of male bonding. Early

World War I films often dealt with American citizens volunteering for

the French, British, or Canadian armies. Later films showed Ameri-

can troops as the deciding factor in the European victory.

D. W. Griffith directed many of the key World War I propaganda

films. Film historians credit Griffith with inventing many modern

film techniques, and his impact on the history of the war movie is even

more direct. For example, in his 1915 Civil War epic Birth of a

Nation, Griffith used cross-cutting techniques within battle scenes to

shift from large-scale images of fighting to more intimate moments

focusing on the film’s main characters. Such techniques allowed

future filmmakers to develop individual characters within a larger

historical context of the war. Griffith’s key World War I film was

Hearts of the World (1918), shot partially under war conditions in

France. In this polemical prowar film, Erich Von Stroheim was cast as

an evil and lustful German officer (a role he would repeat in numerous

later films) who attempts to rape and brutally beat Marie (Lillian

Gish). The film’s anti-German sentiment is so strong that Gish’s

WAR MOVIESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

77

boyfriend is willing to kill her in order save her from such a violation

at the hands of the enemy. This depiction of Germans as unrepentantly

evil would influence not only later World War I films, but World War

II films as well.

Few war movies appeared in the years immediately following

the 1918 armistice. The propaganda of the wartime films was no

longer necessary, and the American public seemed inclined to focus

on domestic affairs. However, three movies in the 1920s brought

about a resurgence of interest in World War I. The Big Parade (King

Vidor, 1925) is credited with reviving the war film genre as well as

being the first to realistically depict the war experiences of American

soldiers. The plot, which follows a group of men from their enlistment

through the conflict, would become standard in the later World War

II films.

The following year, the comedy drama What Price Glory?

(Raoul Walsh, 1926), based on the Laurence Stallings and Maxwell

Anderson stage play, follows two marines, Captain Flagg and Ser-

geant Quirt, as they engage in their own personal rivalry over the

same woman while fighting in France. Though the film version does

temper the antiwar sentiment of the original play, the film’s comedy is

sharply contrasted with its graphic and shocking depictions of battle

scenes. Later war movies would often capitalize on what Jeanine

Basinger in The World War II Combat Film would call the ‘‘Quirt/

Flagg relationship’’ by focusing on two adversarial characters serving

in the same platoon.

Wings (William Wellman, 1927), which won the first Academy

Award for Best Picture, introduced a new subgenre of war films: the

air drama. Director Wellman used his war experiences as a pilot for

the Lafayette Flying Corps and the Army Air Service to create

realistic aerial scenes that were accomplished by mounting cameras

on the fighting planes and by using cameramen in other aircraft,

instead of using rear projection effects. The realism and excitement of

these scenes would be surpassed later in Hell’s Angels (Howard

Hughes, 1930), a film that cost over $4 million and that took over

three years to make some of the most spectacular flying scenes ever

filmed. Unlike The Big Parade, these latter two films do not make a

profound statement about the war, and their popularity was based

primarily on sheer spectacle and excitement. John Monk Saunders, a

veteran pilot and the original writer of Wings, would later write air

dramas, such as Ace of Aces (J. Walter Ruben, 1933), The Dawn

Patrol (Howard Hawks, 1930; remade by Edmund Goulding, 1938),

and The Eagle and the Hawk (Stuart Walker, 1933), that openly

criticized the senseless waste of the war and starkly represented the

mental strain suffered by pilots, yet still remained true to the adven-

turous nature of the subgenre.

The strongest antiwar statement made following World War I

came in Lewis Milestone’s 1930 adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s

novel All Quiet on the Western Front. This film begins with young

German men enthusiastically volunteering to fight for their country.

However, they quickly learn that this war has nothing to do with

honor and glory, and the mental breakdown and violent death of these

soldiers is depicted in graphic detail. The realism of the battle scenes,

including the image of two disembodied hands clutching a barbed

wire, accounts for this film’s continued status as one of the great war

films of the century. The final shot of Paul Baumer (played by Lew

Ayres) dying as he reaches for a butterfly just outside his trench

remains one of the most haunting and effective images in any war

film. Even after World War II, the Great War served as the setting for

profound antiwar commentary, including Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of

Glory (1957) and Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun (1971).

As America entered World War II, however, Hollywood needed

to reverse this antiwar sentiment by creating films that demonstrated

American heroism and success in the earlier war. In Sergeant York

(Howard Hawks, 1941), Gary Cooper’s Alvin York, who went from

devout pacifist to America’s greatest war hero, provides a counter-

image to the one created in such films as All Quiet on the Western

Front. The film also showed the potential for individual heroic

achievement and served as significant propaganda for the American

war effort.

World War II films have a clearly defined sense of good and evil.

As in the previous war, the enemies were presented not as complex

human beings but as two-dimensional caricatures, designed to gener-

ate hate and loathing in the audience. Most films created during the

war years focused on the adventure and glory of warfare, as well as

the strength of both the U. S. military and the American spirit. In

addition, most World War II films had a romantic subplot. The female

love interests were either sweethearts pining away at the homefront;

nurses, AWACs, or reporters serving some military duty; or Europe-

an, usually French, women whom the G.I.’s meet while on leave.

Often, the films followed soldiers from enlistment or training to

combat. These formulas were sometimes mixed in with several

variables, such as military branches or European or Pacific locales, to

create a variety of successful films.

Surprisingly, most of the early World War II combat films made

in 1942 and 1943, such as Wake Island (John Farrow, 1942) and

Bataan (Tay Garnett, 1943), focused more on catastrophic American

defeats than on the victories. Wake Island, the first large-scale combat

film of World War II, closely followed a group of soldiers until they

were all killed in the ensuing battle. Both films received the support of

the U.S. government, and despite showing terrible defeats, these films

mobilized popular support for the war and proved to be useful

propaganda tools.

Few figures are more synonymous with the war movie than John

Wayne. Just as in his Westerns, John Wayne represented the ideal of

American masculinity in a persona that exemplified the hard, deter-

mined, yet compassionate soldier. Such a persona is evident in such

wartime films as Flying Tigers (1942), The Fighting Seabees (1944),

They Were Expendable (1945), and Back to Bataan (1945), and in

postwar films like The Sands of Iwo Jima (1949), Flying Leathernecks

(1951), and In Harm’s Way (1965). These films follow the basic

formulas of World War II movies, and Wayne repeated the same basic

character in each. Although Wayne was criticized in later years for

such repetitive, formulaic performances, he created an iconic hero,

and his films were tremendous successes and morale boosters.

As the Second World War came to a close, movies like The Story

of G. I. Joe (William Wellman, 1945) and A Walk in the Sun (Lewis

Milestone, 1946) moved away from the patriotism and heroics of

films made in the previous years of the war and toward a more

realistic depiction of American soldiers in battle that emphasized the

human cost of war over the glory of victory. Wellman continued to

demythologize warfare in the 1949 film Battleground, which re-

ceived an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture. These three

films follow similar episodic plots focusing on a group of American

soldiers, many of whom are killed through the course of the film. In

WAR MOVIES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

78

the opening of A Walk in the Sun, Burgess Meredith (who also stars as

famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle in The Story of G. I. Joe)

describes the ethnic, class, and cultural diversity of his platoon:

There was Tyne, who never had much urge to travel.

Providence, Rhode Island may not be much as cities go,

but it was all he wanted, a one town man; Rivera, Italian

American, likes opera and would like a wife and kid,

plenty of kids; Friedman, lathe operator and amateur

boxing champ, New York City; Windy, minister’s son,

Canton, Ohio, used to take long walks alone and just

think; . . . Sergeant Ward, a farmer who knows his soil, a

good farmer; McWilliams, first aid man, slow, South-

ern, dependable; Archenbeau, platoon scout and proph-

et, talks a lot but he’s all right; Porter, Sergeant Porter,

. . . he has a lot on his mind . . . ; Tranella speaks two

languages: Italian and Brooklyn.

This conventional Hollywood platoon became a stereotype in

the American war movie with an ensemble cast, but in these early

examples, this broad demographic representation was used to empha-

size the impact of the war on America as a whole.

Following the war, Hollywood war films began to examine the

complexities of warfare, exposing the fallibility and brutality of

military authority by addressing the mental strain inflicted on war’s

participants and by showing the enemy as complex, human, and

sympathetic. Gregory Peck in 12 O’Clock High (Henry King, 1949) is

shown to be a vulnerable hero suffering a mental breakdown during

the war. In From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953), the enemy

is not the Axis powers, but the bullying, violent, murderous military

authorities such as Ernest Borgnine’s Fatso. In The Caine Mutiny

(Edward Dmytryk, 1954), Humphrey Bogart’s emotionally unstable

Captain Queeg proves to be more of a danger to his men than any

enemy is. In The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957), the

Japanese prison camp commander is portrayed as a man caught

between his sense of duty and honor for his country and his sympathy

and respect for the prisoners. This is not to say that the tradition of

heroic war movies did not continue. Films like To Hell and Back

(Jesse Hibbs, 1955), the story of Audie Murphy (played by himself),

America’s most decorated war hero, as well as The Great Escape

(John Sturges, 1963) and The Dirty Dozen (Robert Aldrich, 1967),

continued to show the more adventurous and exciting side of the

conflict. But into the 1960s and 1970s, in films like The Longest Day

(Ken Annakin, et al, 1962) and Patton (Franklin J. Schaffner, 1970),

Hollywood filmmakers increasingly delved into a critical examina-

tion of American militarism, reflecting the general disillusion of

Americans as the Vietnam conflict escalated.

In 1998, the release of two World War II movies, Saving Private

Ryan and The Thin Red Line raised the level of realistic violence

depicted in the war movie to a new level. Steven Spielberg’s Saving

Private Ryan follows a fairly standard plot of a small group of soldiers

sent on a mission to find one man lost in France during the Normandy

invasion. The first thirty minutes of the movie, showing the mass

slaughter that occurred in the opening minutes of the invasion of

Omaha Beach, contain the most graphically violent and disturbing

combat scenes presented in a fictional film. Terence Malik’s The Thin

Red Line is equally violent, but this film about the invasion of

Guadalcanal focuses more on the contrast between combat and the

introspective moments available to soldiers during the lulls in battle.

Both films rely on new developments in special effects and camera

technology that allow for even more graphic and realistic depictions

of military violence.

Of the more than 50 films made about the Korean War between

1951 and 1963, most presented the enemy as one-sided villains, and

few moved beyond the standard cliches of the Hollywood World War

II films. Two exceptions appeared early in the war. Samuel Fuller’s

Steel Helmet and Fixed Bayonets, both released in 1951, take a harsh,

uncompromising, and realistic look at the stress suffered by soldiers

while keeping to the standard plot that follows a diverse platoon

through the conflict. The characters in Fuller’s films are often plagued

with doubts and fears, and they are more concerned with the struggle

to survive than with any potential acts of heroism.

The controversy surrounding the Vietnam conflict caused Hol-

lywood to shy away from it as a subject for war films while the

conflict was ongoing. The only exception is John Wayne’s 1968

directorial debut, The Green Berets. This film largely consists of Cold

War propaganda justifying America’s presence in Vietnam. Wayne

transferred his World War II movie persona to this film, a persona that

was clearly the product of another time. While the film was a box

office success, it stands out as an anomaly in the development of the

Vietnam War movie, which, in the late 1970s and 1980s, would

approach the war much more critically. The Deer Hunter (Michael

Cimino, 1978) and Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

were among the first films to criticize the Vietnam War from a combat

perspective. Both films contain graphic images of the most horrify-

ing, and often surreal, aspects of the war. The Russian roulette scenes

in The Deer Hunter show the extremes of mental and physical torture

suffered by American prisoners of war, and the scene in Apocalypse

Now where Colonel Kilgore orders a helicopter raid on a Viet Cong

village so his men can surf on a nearby beach illustrates the extreme

level of absurdity in this war. The absurdity of the Vietnam War

would be addressed later in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket

(1987), a film that ends with a platoon spontaneously singing the

Mickey Mouse Club theme in unison.

One of the most successful Vietnam War films was Oliver

Stone’s 1986 Academy Award winner, Platoon. While this film does

have a strong antiwar message, it follows a fairly standard war-movie

plot, following the experiences of a naïve young volunteer (played by

Charlie Sheen) as he becomes increasingly disillusioned by the

fighting. The film also follows a clear good-vs.-evil binary, but

instead of America representing good and the Viet Cong representing

evil, these moral forces are represented by two American sergeants.

Tom Berenger’s Barnes brutally terrorizes a native village early in the

film, while Willem Dafoe’s Elias strongly resists this descent into

barbarism and tries to maintain high moral standards in an immoral

environment. The success of Platoon resulted in a spate of Vietnam

War films in the late 1980s, but their numbers never reached the level

and density that occurred during World War II and the Korean War. In

addition, all Vietnam War films made after 1978 engage in some level

of criticism of the war, and none present themselves as the straightfor-

ward adventures that appeared in films about the earlier wars.

In general, films made during wartime emphasize glory, honor,

and patriotic values, and it is only in the years following the wars that

these values are analyzed and criticized. As filmmaking technology

WAR OF THE WORLDSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

79

has changed and improved throughout the century, American

filmmakers have achieved greater levels of realism in war movies,

and these films collectively have enhanced and influenced Ameri-

cans’ awareness of the conditions of war.

—Andrew J. Kunka

F

URTHER READING:

Basinger, Jeanine. The World War II Combat Film: Anatomy of a

Genre. New York, Columbia University Press, 1986.

Dick, Bernard F. The Star-Spangled Screen: The American World

War II Film. Lexington, The University of Kentucky Press, 1985.

Dittmar, Linda and Gene Michaud, editors. From Hanoi to Holly-

wood: The Vietnam War in American Film. New Brunswick,

Rutgers University Press, 1991.

Doherty, Thomas. Projections of War: Hollywood, American Cul-

ture, and World War II. New York, Columbia University

Press, 1993.

Langman, Larry and Ed Borg. Encyclopedia of American War Films.

New York, Garland, 1989.

Quirk, Lawrence J. Great War Films. New York, Citadel, 1994.

Rubin, Steven Jay. Combat Films. Jefferson, North Carolina,

McFarland, 1981.

Suid, Lawrence H. Guts and Glory: Great American War Movies.

Reading, Massachusetts, Addison-Wesley, 1978.

War of the Worlds

Broadcast on October 30, 1938, Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre

radio dramatization of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds engendered a

mass panic in which millions of Americans believed they were being

invaded by Martians; in so doing, the broadcast dramatically demon-

strated the nascent power of mass media in American culture.

The Mercury Theatre group, headed by the 23-year-old Welles,

had built a small national audience with its weekly radio adaptations

of literary classics such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Welles, his partner John Houseman, and writer Howard Koch col-

laborated on the hour-long scripts. The trio nearly scrapped their War

of the Worlds adaptation, as Koch’s faithful approximation of the

novel did not translate well in rehearsals. The group decided to stick

with the project after re-working the script to mirror a news broadcast.

Nevertheless, as group members and even Welles himself later

recalled, the feeling in the studio on the day of the broadcast was that

War of the Worlds would not be a successful production.

The show commenced at 8 p.m. that Halloween eve, following

an introduction by a CBS announcer which presented Wells’ novel as

the subject of the forthcoming dramatization. In the first 10 minutes of

the broadcast, Welles masterfully built dramatic tension by juxtapos-

ing fireside chat-styled meditations on renewed American prosperity

with increasingly frequent news bulletins on atmospheric distur-

bances detected by astronomers across the United States. Just as

Cover of The War of the Worlds, by H.G. Wells.

thousands of listeners switched over from the more popular Charlie

McCarthy show (a less-than-compelling singer had just been intro-

duced), Welles’ group delivered a frantic news report from the small

town of Grovers Mill, New Jersey, where Martians had landed and

wiped out an entire United States military force: ‘‘A humped shape is

rising out of the pit. I can make out a small beam of light against a

mirror. What’s that? There’s a jet of flame springing from that mirror,

and it leaps right at the advancing men. It strikes them head on! Good

Lord! They’re turning into flame!’’ As the broadcast followed the

progress of the Martians up the East Coast, the reports became even

more dire. ‘‘People are falling like flies,’’ Welles reported. ‘‘No more

defense. Our army wiped out . . . artillery, air force, everything wiped

out. This may be the last broadcast.’’ An actor portraying the

Secretary of the Interior informed listeners that President Franklin

Delano Roosevelt had declared a national emergency.

As the dramatization continued, thousands of Americans pan-

icked. In New York City, hundreds of people jammed railroad and bus

stations to escape the menace. In Birmingham, Alabama, sorority

women at a local college lined up at campus telephones to speak to

parents and loved ones for the last time. In Pittsburgh, a man found his

wife in the bathroom, clutching a poison bottle and yelling ‘‘I’d rather

WARHOL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

80

die this way than that.’’ And, in a favorite story of Welles’, actor John

Barrymore, upon hearing the broadcast, drunkenly took to his back-

yard, where he unleashed his Great Danes from their doghouse with

the admonition: ‘‘Fend for yourselves!’’ It has been estimated that 12

percent of the radio audience heard the broadcast and more than half

that number took it seriously; by sociologist Hadley Cantril’s ac-

count, which was published in a landmark contemporary study

sponsored by the Rockefeller foundation, more than a million people

were frightened by Welles’ broadcast. Cantril’s demographic survey

placed the strongest currents of fear among less-educated people and

poor Southern folk.

Welles concluded his broadcast with a re-statement of the

fictionality of the presentation (‘‘The Mercury Theatre’s own radio

version of dressing up in a sheet and saying ‘Boo!’’’ as Welles put it),

but the hysteria continued well into the night. CBS was inundated

with calls; newspaper switchboards were jammed, and mobs contin-

ued to crowd the streets of New York and northern New Jersey. When

the truth became apparent, public hysteria turned into ire directed at

CBS. Hundreds threatened lawsuits against the network, not the least

of which was from H.G. Wells himself; the Federal Communications

Commission promised a full-fledged inquiry, and the New York City

police, for a time, even contemplated arresting Welles. As calmer

heads prevailed, the public furor died down, and Welles became an

overnight sensation; many of his biographers claim that without the

celebrity engendered by the War of the Worlds broadcast, Welles

might never have been able to bring his craft to Hollywood, where he

became a celebrated director with films such as Citizen Kane (1941)

and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

The War of the Worlds episode highlighted the emerging power

of mass media over the American public. It demonstrated the power

of the media to form and shape opinion in American culture, and also

the passive willingness on the part of the public to place its faith in the

legitimacy of sound and image. Ironically, War of the Worlds

represented one of radio’s final assertions of power within the media

sphere; by the 1950s, television had replaced radio as the dominant

force in mass culture.

Scholars assert that Welles’ broadcast was so widely believed

because it struck a particular chord with Americans in the years before

World War II. The show aired just after the Munich crisis, to which

Welles alluded at the outset of the broadcast, and the recent interna-

tional conflict may have influenced some to believe that the reported

invasion was not extraterrestrial at all. Sociologists have also located

the show’s resonance in the latent anxiety of the general population,

engendered by years of economic depression. ‘‘On the surface, the

broadcast was implausible and contradictory, but that didn’t matter,’’

asserts Joel Cooper. ‘‘In that one instance, people had an immediate

explanation for all the unease and disquiet they had been feeling. And

suddenly, they could do something. They could gather their families.

They could run.’’

War of the Worlds remained a vibrant part of American popular

culture in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1953, Byron

Haskin produced a Hollywood film about the broadcast and, from

1988-1990, a television series inspired by Welles’ take on War of the

Worlds enjoyed a successful run. In 1988, the fiftieth anniversary of

the broadcast, public radio stations across America aired an ambitious

remake of War of the Worlds starring Jason Robards and featuring the

Oscar-winning sound effects of Randy Thom; the citizens of Grovers

Mill commemorated their town’s role in the historic broadcast with a

four-day festival that culminated with the unveiling of a bronze statue

of Welles at a microphone and a rapt family gathered around its radio.

Up until his death in 1985, Welles would never reveal whether

he had anticipated the massive misinterpretation of his radio drama.

Whether intended as a hoax or not, however, the landmark War of the

Worlds broadcast demonstrated the American public’s preference for

reading media’s sound—and later its images—as truth rather

than fiction.

—Scott Tribble

F

URTHER READING:

Baughman, James. The Republic of Mass Culture: Journalism,

Filmmaking, and Broadcasting in America Since 1941. Baltimore

and London, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Brown, Robert J. Manipulating the Ether: The Power of Broadcast

Radio in Thirties America. Jefferson, McFarland & Co., 1998.

Cantril, Hadley. The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology

of Panic with the Complete Script of the Famous Orson Welles

Broadcast. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1940.

Higham, Charles. Orson Welles: The Rise and Fall of an American

Genius. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1985.

Thomson, David. Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles. New York,

Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Warhol, Andy (1928-1987)

Andy Warhol was the most renowned Pop artist in the 1960s

and, more generally, one of the most important artists of the twentieth

century. His boundless and apparently effortless creativity expressed

itself in many forms. He was a commercial designer, painter, print-

maker, filmmaker, and publisher.

Although Warhol was intentionally obscure about his back-

ground, he was born Andrew Warhola, the son of a Czech Roman

Catholic emigrant miner, in remote Forest City, Pennsylvania. After

his father’s early death, Warhol enrolled in Pittsburgh’s Carnegie

Institute of Technology as an art student in 1946. At this time he

worked as a window decorator in a Pittsburgh department store. By

1950 he had shortened his name to Andy Warhol, and had moved to

New York where his reputation as a designer quickly blossomed.

Besides doing graphic work for magazines such as Vogue and

Harper’s Bazaar, he won awards for his advertising designs, particu-

larly those for I. Miller shoes. It is clear that had he never become a

fine artist, he would nevertheless have been one of the most important

designers in the postwar period. It was during these years Warhol

dyed his hair the signature silver color that he would maintain for the

rest of his life.

In 1960, the year Warhol began to paint, he made some of the

earliest works that could be called Pop Art. His large paintings of

Dick Tracy could be seen in Lord and Taylor’s store windows on Fifth