Pavlac B.A. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

336

CHAPTER 14

lay in ruins. Among the survivors, tens of millions of people had been displaced as

soldiers, prisoners, forced laborers, or refugees. Some nations began to carry out

ethnic removals to clean up some of their lingering nationality problems. Millions

of Germans who fled or were forcibly ejected from areas subsequently occupied by

Russia, Poland, or Czechoslovakia gained little sympathy. Also, Yugoslavia kicked

out Italians. Even Bulgaria and Greece seized the opportunity to expel thousands

of Turks, even though Turkey had remained neutral during the war. Never before

had such numbers of people been forced to migrate. Many displaced persons

lacked homes and jobs, although many states became much more ethnically uni-

form, as nationalistic ideals demanded. The Allied armies that occupied the

defeated nations organized the slow rebuilding of their societies and eliminated the

fascist policies that had caused the war.

The victorious Allies showcased the defeat of the fascists by conducting trials

for war crimes against humanity. The slaughter and genocide of civilians during the

war were considered so horrific that the victors undertook the unusual measure of

convening international courts. As a result of the Nuremburg Trials in Germany,

twenty-five captured Nazi leaders were hanged. Over the next several years a few

dozen lower-ranking Nazis also faced judgment and execution.

Not all fascist criminals came to justice, however. Some Nazi sympathizers, col-

laborators, and even high-ranking officials managed to escape, many fleeing to sym-

pathetic fascist regimes in Latin America, sometimes with the knowledge of local

governments. In particular, Nazi scientists, especially those responsible for work on

rockets and jets, were smuggled to one victor or another. In Asia, the trials for

Japanese war criminals were much less thorough. Emperor Hirohito of Japan had

declared himself no longer a god, so the American occupiers retained him in office

and absolved him of all blame for the war and atrocities committed by Japanese

soldiers. Comparatively few Japanese war crimes were exposed or punished, espe-

cially since the United States was becoming less concerned about its wartime

enemy, Japan, than about its wartime ally, Russia.

That the victorious wartime alliance fell apart so quickly surprised and confused

many. Certainly, the victory in World War II created a unique geopolitical situation.

The great powers, powerful countries who could assert military action around the

world, had dominated international politics since the nineteenth century. By the

end of World War II, though, England and its British Empire were clearly exhausted

by the effort. France needed to rebuild, as did China, after suffering hard occupa-

tions. Of course, Germany, Italy, and Japan lay in ruins and were occupied by the

Allies. Only the United States and the Soviet Union remained capable of effective

global action. Indeed, they had risen to the status of superpowers. They had large

populations (over a hundred million), were industrialized, occupied vast continen-

tal land masses, were rich in agricultural land and natural resources, and possessed

massive military forces. The other declining great powers could not hope to match

them.

Equal in power, the United States and the U.S.S.R. were nevertheless divided

by opposing ideologies (see table 14.1). The Soviet Union was a totalitarian dicta-

torship with a secret police, the KGB; the United States worked along more republi-

PAGE 336.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:40:37 PS

AWORLDDIVIDED

337

Table 14.1. Comparison and Contrast between the United States of America and the

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

Politics Economy Society Culture Belief

U.S.S.R. soviet, communism: classless society rigid censorship, atheism,

totalitarian, centralized, (party elites vs. state-controlled persecuted

one party state-planned masses); free press and arts Russian

economy public education Orthodox

Church

U.S.A. federal, mixed upper, middle, limited religious

democratic- economy: and lower classes; censorship, toleration,

republican, laissez-faire private and free press, separation

two parties capitalism public profit-making of church

and socialism education arts and state,

nominally

Christian

Note: The U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R. represented different aspects of the Western heritage that competed

for people’s allegiance during the Cold War.

can and constitutionalist principles. The U.S.S.R. used centralized state planning

for its economy (often called communism); the United States practiced capitalism

in a mixed economy of some socialistic regulation and competitive, semifree mar-

kets.

1

Russia proclaimed itself to have outgrown nationalistic and class divisions

(although its party elites led a significantly better life than its common workers);

the United States, despite a growing middle class, remained divided into significant

economic disparities between rich and poor, often based on sex, ethnicity, and

race. The Russian government rigidly controlled and censored its media; busi-

nesses, through their advertising dollars, influenced the American media. The

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics proudly proclaimed itself to be atheistic (osten-

sibly believing in the dogmas of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin) and restricted worship by

Orthodox Christians; the United States of America asserted religious freedom and

toleration, while the majority of citizens attended diverse Christian churches. Com-

munist Russia lost sight of the individual in its mania for the collective—many could

suffer so the group could succeed; capitalist America awkwardly juggled individual

rights and communal responsibility.

The differences in these practices and ideologies did not necessarily mean that

a conflict was inevitable. Both sides could have decided to live and let live. Yet both

sides envisioned their own path as the only suitable way for everyone on earth to

live. Each state tried to dominate the world with its own vision of order, echoing

the clashes of the past, whether between the Athenian creative individualism versus

Spartan disciplined egalitarianism of the Peloponnesian Wars, or revolutionary

1. As part of this ideological war, the term capitalism was transformed to oppose the ‘‘com-

munism’’ of central planning of the economy by government. Thus, today many people define

capitalism as the private ownership of the means of production instead of its simpler definition

as the practice of reinvesting profits. Soviet-style ‘‘communism’’ likewise differed from Marx’s

ideal of common ownership.

PAGE 337.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:40:37 PS

338

CHAPTER 14

France against commercial Great Britain during the Wars of the Coalitions. The

world split up between them. The United States and its allies often called them-

selves ‘‘the West.’’ The Soviet Union and its allies were often called the ‘‘Eastern

bloc’’ because of their center in Eastern Europe or from their association with China

in East Asia. A more accurate terminology arose of the ‘‘First World’’ (the nations

associated with the United States), the ‘‘Second World’’ (the nations associated with

the Soviet Union), and the ‘‘Third World’’ (Latin America and the soon to be newly

liberated colonial areas of Asia and Africa).

The splits between these blocs widened during Allied planning conferences as

World War II wound down. First, in February 1945 at the Soviet Black Sea resort of

Yalta, the ‘‘Big Three’’—Stalin for the Soviet Union, Roosevelt for the United States,

and Churchill for Britain—began to seriously plan for the postwar world after their

inevitable victory. They agreed in principle that Europe would be divided into

spheres of influence, thus applying the language of imperialism to Europe itself.

Southern Europe went to the British, while much of Eastern Europe came under

the Russian sphere. Under the guidance of the British and Russians, self-govern-

ment in different nations was supposed to be restored. The only sphere the United

States committed itself to was joining Britain and Russia in occupying Germany.

After Germany’s defeat, but before Japan’s surrender, the ‘‘Big Three’’ met

again at Potsdam in July 1945, although two of the leaders had been replaced.

Stalin still represented the U.S.S.R. In the meantime, Churchill had been voted out

as prime minister to be replaced by Labour Party leader Clement Atlee. And Harry

Truman (r. 1945–1953) had succeeded to the American presidency following the

death of FDR in April. These three shaped up plans for German occupation (adding

France as a fourth occupier), denazification and the war crimes trials, restoration

and occupation of a separate Austria, and peace treaties for the minor Axis mem-

bers. While many questions remained open, the settlements still seemed to be

going well.

One more hope for a unified future of the world was an organization that had

been created by the victorious Allies to prevent new conflict, the United Nations

Organization (UN). The United Nations charter was first signed in San Francisco

on 26 June 1945, as war still raged in Asia. The five victors of World War II (the

United States, the U.S.S.R., Great Britain, France, and, generously, China), became

the permanent members of the Security Council, with veto power over the organi-

zation’s actions. The UN could provide some international regulations and help

with health-care issues. More importantly, when the Security Council agreed, the

organization could quickly and easily commit military forces. Its hope was to use

collective security to maintain peace. The UN’s peacekeeping role has indeed man-

aged to keep many wars and rebellions from growing worse around the world.

From the Congo to Cyprus, peacekeepers have saved some lives, but the UN can

solve an issue only when a superpower does not object.

Soon enough, the superpowers diverged, as the temptations of occupation

proved too strong for Stalin. Stalin soon began sovietization of the states in his

sphere of influence (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania, Bulgaria, and its

occupied zones of Germany). Believing it his right to have friendly neighbors in

PAGE 338.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:40:38 PS

AWORLDDIVIDED

339

Eastern Europe, Stalin helped communist parties take over governments, which

then claimed to be people’s democratic republics. As in the Soviet Union, these

regimes lacked opposition parties but still conducted elections. The new commu-

nist leaders purged, arrested, and executed not just fascists but also liberals, conser-

vatives, and socialists unwilling to submit. Using the excuse of rebuilding from the

war’s devastation, communist governments nationalized businesses and property.

As the Soviet armies stayed and the new leaders of Eastern European states took

direction from Moscow, these satellite or ‘‘puppet’’ states were becoming protector-

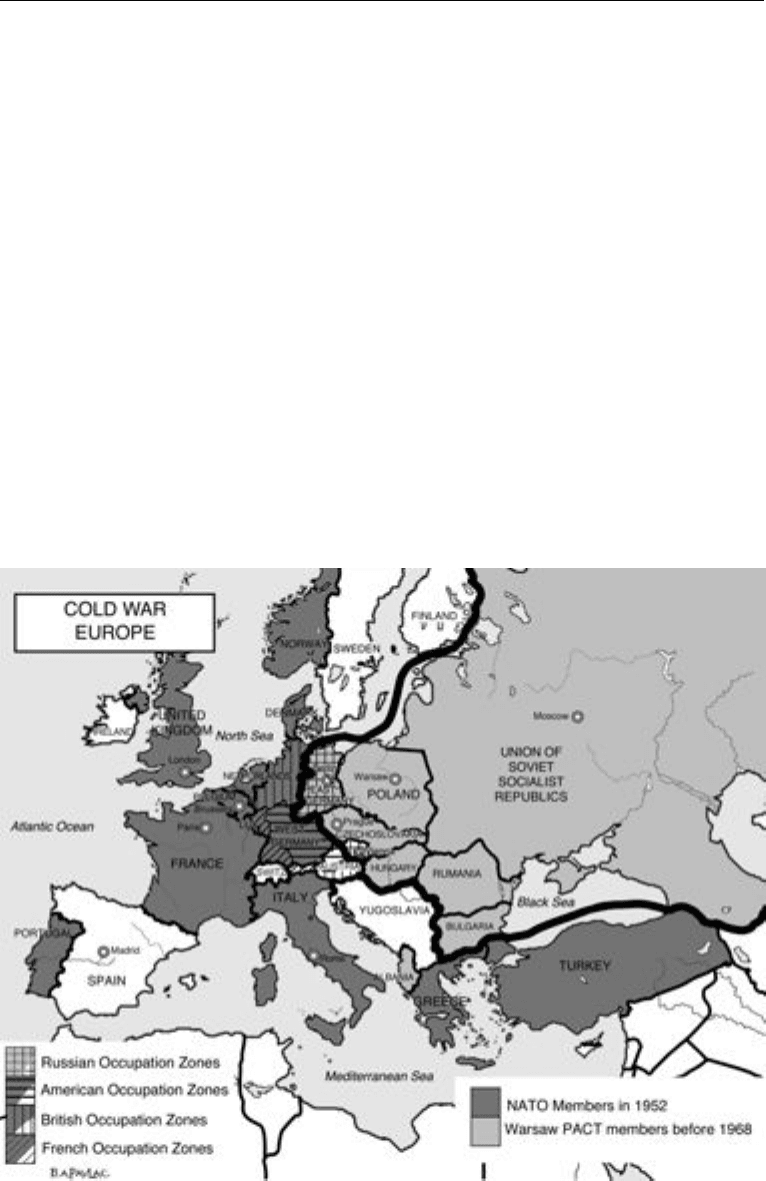

ates rather than merely falling under a sphere of influence. These changes led the

retired British prime minister Winston Churchill to use the metaphor of the ‘‘Iron

Curtain’’ separating communist oppression from ‘‘Christian civilization’’ (see map

14.1).

At first, Americans ignored Churchill’s warning. But growing communist-backed

insurgencies in Greece and Turkey led the Americans to accept Churchill’s con-

cerns. Soviet intervention in these new areas led Americans to believe Stalin was

expanding beyond the provisions of Yalta and Potsdam. President Truman decided

to carry out a policy called containment, to try to limit the influence of the Soviet

Union in several ways. In his speech creating the Truman Doctrine, he promised

aid to governments resisting hostile seizures of power by foreigners or even by

armed minorities of natives. He explicitly contrasted the freedom of the United

Map 14.1. Cold War Europe

PAGE 339.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:41:08 PS

340

CHAPTER 14

States with the tyranny of Russia. The United States followed up with military aid to

the Greeks and Turks, who crushed the insurgencies. Through the Marshall Plan

(or European Recovery Program) the United States also provided money to Euro-

pean states struggling with a lack of capital in the wake of the war. A small American

investment of seventeen million dollars helped rebuild Europe and weaken the

appeal of communism. To further combat communism, a new American Central

Intelligence Agency (CIA) gathered information and carried out covert operations

(including supporting armed intervention, sabotage, and assassination).

Even these heightening tensions only solidified into an enduring dispute cen-

tering on occupied Germany. As the war ended, both Germany and Austria had

been divided into zones run by the armies of each of the four victorious powers,

Britain, France, the United States, and the Soviet Union. They also divided and

occupied the capital cities, Vienna and Berlin, located in the middle of their respec-

tive Soviet zones. While the four Allies quickly granted some self-government to

Austria, they could not agree about Germany. The three Western occupiers wanted

Germany to become more independent as soon as possible. Meanwhile, the Soviet

Union plundered its East German occupation zone for materials to use in rebuild-

ing its own devastated territories. It also feared that a united Germany could one

day invade Russia again.

In June 1948, when the British, French, and Americans took steps to allow a

new currency in the Western zones, the Russians initiated the Berlin Blockade

(1948–1949), shutting down the border crossings, in violation of treaties and agree-

ments. The Allies could have, with legitimacy, used force to oppose these Russian

moves. Instead of becoming a ‘‘hot’’ war, with each side unleashing firepower

against the other, the war remained ‘‘cold.’’ Each side held to a basic principle:

Nobody wanted World War III because it would mean the end

of the world.

With ‘‘weapons of mass destruction’’ of atomic, biological, and chemical technol-

ogy, the superpowers could exterminate huge numbers of people. Even a small

military action against the Russians would have, of course, created a counterattack,

with the two superpowers in a shooting war. If it escalated to the use of atomic,

biological, and chemical weapons, World War III (a war including several great

powers and superpowers against one another) could wipe out all humanity or at

least destroy all modern civilized ways of life. Only in fiction did people entertain

nuclear war, whether realistically predicting the catastrophic results as in the movie

On the Beach, or in James Bond movies where evil madmen hoped to spark world

destruction.

A nonconfrontational solution, the Berlin Airlift, succeeded in the short term.

The Western allies supplied the isolated city using airplanes to fly over the Russian

barricades. Over nine hundred flights per day provided seven thousand tons of

food and fuel to keep the modern city of two million people going for over a year.

Enormous sums of money were spent, and men died (in several plane crashes), but

PAGE 340.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:41:09 PS

AWORLDDIVIDED

341

no shots were fired. Then one day, the Russians opened the border again. Soon

afterward, a new German state appeared in the West, the Federal Republic of Ger-

many, based on the values of the Western Allies. Subsequently, the Russians

endorsed the German Democratic Republic in the East, based on sovietization.

Both sides built new alliance systems. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization

(NATO) bound together most Western European states with Canada and the United

States in a mutual defense pact. Sweden and Switzerland retained their neutrality.

Russia arranged the Warsaw Pact with its satellite states (Poland, East Germany,

Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania, and Bulgaria) to better coordinate their mili-

tary forces in opposition to NATO. These military alliances, ready to fight World War

III, faced one another across the barbed wire and barricades that ran through the

heart of German field and forest. Still, the divisions solved the ‘‘German problem,’’

at least temporarily.

An arms race continued to threaten the world nevertheless. By 1949, the Rus-

sians had their own atomic bomb. Then, by 1952, the United States developed the

hydrogen or H-bomb, on which most modern thermonuclear weapons are based.

Each H-bomb can have the explosive power of hundreds of times the Hiroshima

and Nagasaki devices (each of which destroyed an entire city). Aided by information

gained through espionage, however, the Russians soon tested a nuclear weapon of

their own. With or without spying, nuclear proliferation remained inevitable. With

enough time, effort, money, and access to supplies, any nation can harness science

to build nuclear as well as biological, chemical, and any number of conventional

weapons. Throughout the Cold War, both sides kept shortsightedly relying on some

technological superiority or another, only to see it vanish with the next application

of scientific effort by the other side.

At first, complexity and cost usually meant that nuclear weapons remained in

the hands of great powers. The British were next with nuclear bombs in the 1960s,

quickly followed by the French. Then the Soviet ally China came next. By the 1990s,

India tested its prototype bomb, which prompted Pakistan to produce its own. It is

unclear when South Africa and Israel got theirs, probably sometime in the 1970s,

although South Africa has given up its technology. Currently, North Korea and Iran

are striving to join the ‘‘nuclear club.’’

These states, though, each held only a handful of nuclear weapons. The two

superpowers, however, held enough to destroy the world many times over. As tech-

nicians perfected ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles) by the late 1950s, any

target on the globe was vulnerable to vaporization. By 1977, the superpowers had

stockpiled tens of thousands of nuclear devices—with the equivalent of about fif-

teen tons of TNT per person on the planet.

During the Cold War, the superpowers never pressed the button to end human

history with the explosion of nuclear weapons. Instead, they relied on deterrence

(preventing war through the fear that if one side starts nuclear war, the other will

finish it). The American policy of deterrence was aptly called MAD, the acronym for

‘‘mutually assured destruction.’’ Both sides did play at brinkmanship (threatening

to go to war in order to get your opponent to back down on some political point).

In reaction to this threat to civilization, some citizens of Western states began calling

for nuclear disarmament. Governments also realized that they could not endlessly

build risk into global politics. As a result, some areas became off limits for weapons

PAGE 341.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:41:09 PS

342

CHAPTER 14

(Antarctica, the ocean floors, and outer space). Other countries were discouraged

from acquiring their own weapons through nonproliferation treaties beginning in

1968; and through the 1960s and into the 1980s the two superpowers negotiated

on limits or mutual inspections of numbers and use of arms.

For the next several decades after the Berlin Blockade, the Cold War was on.

This third great world war of the twentieth century was unique in the history of

politics. Like its predecessors, World Wars I and II, the Cold War cost enormous

amounts of money, destroyed a lot of territory, cost many lives, and changed the

destinies of nations. But unlike those other two conflicts, the main opponents, the

Soviet Union and the United States, did not actually fight each other, despite a

string of international crises. Instead, they encouraged other people to do the kill-

ing, sometimes supplying intelligence, equipment, advice, and even soldiers.

Although the Cold War was an ideological civil war of the West, it weighed on every

international and many a domestic decision of almost all countries in the world.

Review: How did the winning alliance of World War II split into the mutual hostility of

the Cold War?

Response:

MAKING MONEY

Rather than fight the Cold War, most Americans would probably have preferred

blissfully to return to expanding the U.S. economy. But the traditional American

isolationism was doomed not only by the events of World War II but by the world-

wide economy led by the United States after the war. Some Western economies

grew so fast that they needed to import immigrant workers for their factories. West-

ern capitalists regularly took advantage of these workers by paying them less than

they would union-organized Western laborers, but even so, such incomes far

exceeded what the foreigners could have earned in their native lands. Notably, West

Germany’s Gastarbeiter (guest workers) from the Balkans helped the German

economy grow. Their labor helped both West Germany and their home countries.

Guest workers typically sent money back to families in their homelands, building

capital for those economies. Their lives in Germany remained isolated, however,

segregated from the main German culture. For a long time, the Germans thought

the workers would go home again, and so they ignored issues of integrating the

PAGE 342.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:41:10 PS

AWORLDDIVIDED

343

Gastarbeiter. Instead, many stayed from one generation to the next. Economic

necessity, rather than defeat in World War II, created an ethnically mixed Germany.

Other European nations accepted immigrants from their colonies as cheap

labor. So many came to England that the British Parliament restricted holders of

British passports from moving from other parts of the Commonwealth to the

mother country. Nevertheless, the numbers of foreign-born residents in Western

European states began to surpass the number of comparable immigrants in the

United States, a nation traditionally much more favorable to immigration. Through-

out Europe the guest workers lived in shabby, crowded apartments lacking services

and facilities, isolated from the main ethnic groups of the nation. This segregation,

however, often allowed foreign workers and their families to maintain many of their

own cultural traditions. Nonetheless, many Europeans long ignored these new resi-

dents as an invisible underclass, often disregarding either possibilities of integration

and acculturation or social disruptions of clashing cultures.

Coming out of World War II, the United States had the strongest internationally

oriented economy, with dominant influence in the International Monetary Fund

and General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). By the 1960s, though, the

other great powers, especially Germany and Japan, had recovered from the devasta-

tion of the war. They then began to offer serious competition to the Americans.

Both Germany and Japan used a socialistic cooperation of government, manage-

ment, and workers to a degree that the Americans, with their antagonistic interests

of owners and unions, could not.

The rapid increase of wealth in the West was a significant victory for socialist

ideas. After World War II, social democratic and Christian socialist parties came to

power in many Western countries. Their gradual, legal, revisionist, state socialism

created the modern welfare state. Germany rebuilt itself in record time, using the

idea of a social market economy. As in a free-market economy, German businesses

were regulated as little as possible. At the same time, the German state enforced

socialist theory, which provided workers with protections for illness, health, old

age, and joblessness, while labor unions gained representation on the boards of

corporations.

For awhile, Great Britain went furthest along the road toward the modern wel-

fare state, although its loss of empire made adjustments difficult. The British swept

away poor laws (which had condemned the poor to prison for debt) and instead

initiated programs to provide a minimum decent standard of living for most people.

Government support and regulation established national health-care programs,

pensions, and unemployment insurance. Public education of high quality, through

the university level, was available for free or at very low cost. Programs sent aid for

housing and food directly to families. Many essential businesses, especially coal,

steel, and public transportation, were nationalized or taken over by the govern-

ment, to be run for the benefit of everyone, not just stockholders. Unfortunately

for economic growth, government management did not provide efficiency, and

some of these firms could not compete well in the world markets.

All over the West, standards of living rose. The social ‘‘safety net’’ provided

more chances for the poor to rise out of poverty. Reliable supplies of electricity and

installation of indoor plumbing became nearly universal. The middle class broad-

PAGE 343.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:41:11 PS

344

CHAPTER 14

ened out to include many of the working class, because social welfare legislation

and union contracts gave workers decent wages and benefits. More people gained

access to labor-saving appliances such as washing machines and automatic dish-

washers. Home ownership increased. Meanwhile, the extremely wealthy continued

to prosper (even if they disliked paying taxes redistributed to help the middle and

poor classes).

This vast increase in wealth also led to an amazing lifestyle change in industrial-

ized nations, especially the United States. Instead of the duality of city and country-

side that had marked the living patterns of civilization since its beginning, most

people began to live in a novel kind of place, the suburbs. Suburbanization meant

a new way of life for the growing middle classes. Suburbs are a blend of traditional

urban living with rural landscapes. People wanted open space (the yard with lawn)

and separate dwellings (the stand-alone home), as well as shopping amenities (the

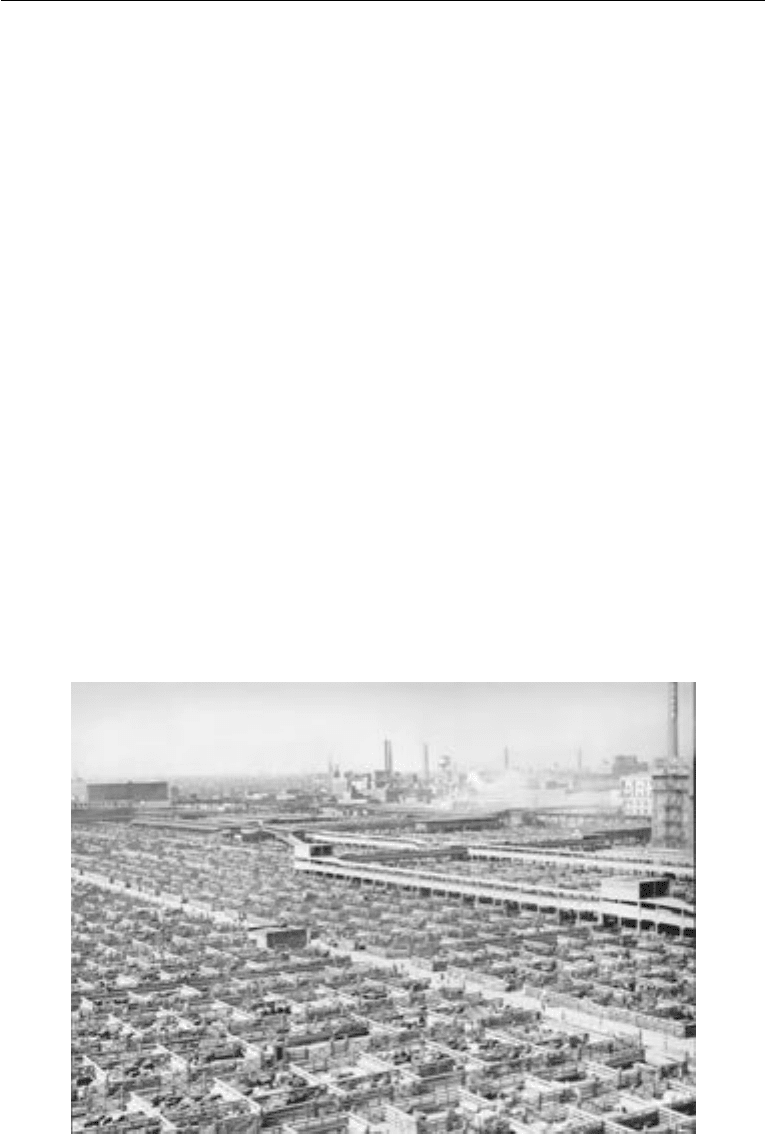

shopping mall). Many jobs, however, continued to be located in the cities (see

figure 14.1). Thus commutes multiplied over vast miles of roads. To meet this need,

production of motor vehicles in the United States soon reached the equivalent of

one car for every man, woman, and child. Huge amounts of new construction

catered to automobiles, from superhighways to parking lots. Europe also suburban-

ized, although more slowly, as it lacked open spaces that could be developed. Both

Western and Eastern European societies aimed to provide consumer products,

whether through capitalistic or communistic means of production. Europeans also

tended to favor mass transportation over commuting by private automobile.

While suburbs had many admirable comforts, their cost tore at the social fabric

of the West, especially in the United States. By definition, living in suburbs required

Figure 14.1. Stockyards in Chicago in 1947 where workers slaughtered

meat for America. Better truck transportation would soon allow owners to

move these sites outside of cities to rural areas.

PAGE 344.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:41:28 PS

AWORLDDIVIDED

345

a good income. Local zoning laws enforced a middle-class status on suburbs. Ameri-

can inner cities of the East and Midwest to which blacks had migrated from the

South before and after World War II became virtual ghettoes as whites fled to live

in suburbs. White men, both middle and working class, could earn enough in the

1950s and 1960s to allow middle-class wives to stay home as domestic managers.

Yet many stay-at-home women felt isolated in their suburban luxury. The economic

shift of the 1970s (see below), however, soon forced women to find jobs, since two

incomes were needed to support the suburban lifestyle, and that meant absentee

parents. Increasingly, children were left home alone. Television provided mindless

entertainment for some. Drugs, consumed behind closed doors, also became

widely used among the children of middle-class parents. In dealing with increased

drug use, many governments decided to take a criminal direction rather than a

medicinal one, leading to larger and larger numbers of incarcerated. By the end of

the century, governments such as those of Switzerland and the Netherlands experi-

mented with legalization and toleration.

This expanded middle class and suburbanization had enormous consequences.

The incredible affluence of the West led to a cultural revolution, as the children of

the post–World War II generation started to come of age. Often called ‘‘baby boom-

ers’’ in the United States, these large numbers of young people had more educa-

tion, opportunities, and wealth than ever before. They criticized the elites of the

‘‘establishment’’ as hypocritically too interested in power, wealth, and the status

quo rather than social justice. In turn, the ‘‘establishment’’ criticized young people

as too obsessed with sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. The popularity of movies, televi-

sion, and recorded music indulged trends toward a counterculture. Rock ’n’ roll

provided a new international youth culture that gained momentum with the British

music group The Beatles (1962–1970), a worldwide sensation. On the one hand,

some Western cultural conservatives worried that the long-haired rockers were as

bad as communists. On the other hand, communists condemned the Beatles as sex-

crazed capitalists.

A sexual revolution arose as part of the new counterculture. Greater freedom

in sexual activity became possible with improvements in preventing pregnancy. In

the late 1950s, pharmaceutical companies introduced reliable contraceptives in the

form of an oral pill. ‘‘The Pill’’ allowed more people to have sex without the risk of

pregnancy, while medically supervised abortions could end pregnancy with relative

safety for a woman. The revolution also encouraged more sex outside the confines

of traditional marriage. Sex became a more noticeable part of literature, instead of

being sold under the table. Courts refused to enforce censorship laws against seri-

ous novels like Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer or art films like I am Curious, Yel-

low. Everything from girlie magazines like Playboy to explicit pornography became

more accessible.

This increasing extramarital sexual activity brought unforeseen medical risks.

The Pill could have side effects, such as blood clots. Even more serious were vene-

real or sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). For a few years in the middle of the

century, the traditional sexual diseases of syphilis and gonorrhea had become treat-

able with modern antibiotics, so many thought sexually transmitted diseases could

be ignored. But new diseases began to develop, as multitudes of human bodies

came into more intimate contact. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

PAGE 345.................

17897$

CH14 10-08-10 09:41:29 PS