NP 100 - Mariners Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 6

160

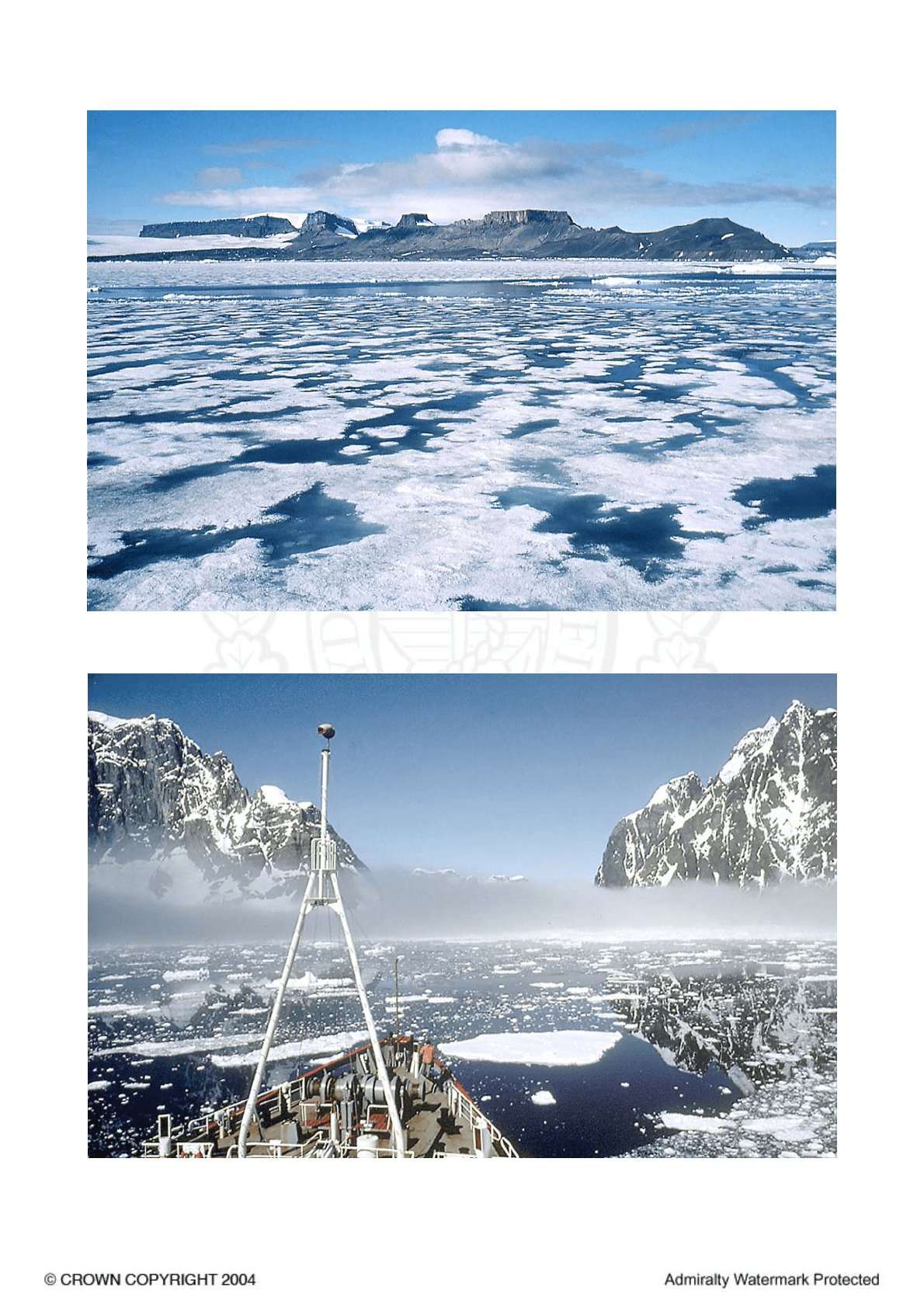

Old ice with puddles forming on top (Photograph 27)

(Photograph − British Antartic Survey)

Very open ice (Photograph 28)

(Photograph − British Antartic Survey)

Home

Contents

Index

CHAPTER 6

161

ICE GLOSSARY

Contents

6.26

This glossary defines descriptive terms in general use for

the various kinds of ice likely to be encountered by the

Mariner. It includes terms given in WMO Sea-Ice

Nomenclature published by the World Meteorological

Organization in 1970 (with its subsequent amendments).

Glossary

6.27

ablation. All processes by which snow, ice or water in any

form are lost from a glacier, floating ice or snow cover.

These include melting, evaporation, calving, wind

erosion and avalanches. Also used to express the

quantities lost by these processes.

accumulation. All processes by which snow, ice or water

in any form are added to a glacier, floating ice or snow

cover. These include direct precipitation of snow, ice or

rain, condensation of ice from vapour, and transport of

snow and ice to a glacier. Also used to express the

quantities added by these processes.

aged ridge. A ridge which has undergone considerable

weathering. These ridges are best described as

undulations.

anchor ice. Submerged ice attached or anchored to the

bottom, irrespective of the nature of its formation.

area of weakness. A satellite-observed area in which either

ice concentration or ice thickness is significantly less

than that in the surrounding areas. Because the condition

is satellite observed, a precise quantitative analysis is not

always possible, but navigation conditions are

significantly easier than in surrounding areas.

bare ice. Ice without snow cover.

belt. A large feature of drift ice arrangement; longer than it

is wide; from 1 km to more than 100 km in width.

bergy bit. A large piece of floating glacier ice, generally

showing less than 5 m above sea level but more than

1 m and normally about 100–300 sq m in areas

(Photographs 1, 17, 19, and 21).

bergy water. An area of freely navigable water in which

ice of land origin is present in concentrations less than

1/10. There may be sea ice present, although the total

concentration of all ice shall not exceed 1/10.

beset. Situation of a vessel surrounded by ice and unable to

move.

big floe. A floe 500–2000 m across.

bight. An extensive crescent-shaped indentation in the ice

edge, formed by either wind or current.

brash ice. Accumulations of floating ice made up of

fragments not more than 2 m across; the wreckage of

other forms of ice. (Photograph 2).

bummock. From the point of view of the submariner, a

downward projection from the underside of the ice

canopy; the counterpart of a hummock.

calving. The breaking away of a mass of ice from an ice

wall, ice front or iceberg.

close ice. Floating ice in which the concentration is 7/10 to

8/10, composed of floes mostly in contact.

(Photograph 10)

compacted ice edge. Close, clear-cut ice edge compacted

by wind or current usually on the windward side of an

area of drift ice.

compacting. Pieces of floating ice are said to be

compacting when they are subjected to a converging

motion, which increases ice concentration and or

produces stresses which may result in ice deformation.

compact ice. Floating ice in which the concentration is

10/10 and no water is visible.

concentration. The ratio in tenths describing the amount of

the sea surface covered by ice as a fraction of the whole

area being considered. Total concentration includes all

stages of development that are present, partial

concentration may refer to the amount of a particular

stage or of a particular form of ice and represents only a

part of the total.

concentration boundary. A line approximating to the

transition between two areas of drift ice with distinctly

different concentrations.

consolidated ice. Floating ice in which the concentration is

10/10 and the floes are frozen together. (Photograph 12)

consolidated ridge. A ridge in which the base has frozen

together.

crack. Any fracture of fast ice, consolidated ice or a single

floe which may have been followed by separation

ranging from a few centimetres to 1 m.

dark nilas. Nilas which is under 5 centimetres in thickness

and is very dark in colour.

deformed ice. A general term for ice which has been

squeezed together and in places forced upwards (and

downwards). Sub-divisions are rafted ice, ridged ice and

hummocked ice.

difficult area. A general qualitative expression to indicate,

in a relative manner, that the severity of ice conditions

prevailing in an area is such that navigation in it is

difficult.

diffused ice edge. Poorly defined ice edge limiting an area

of dispersed ice; usually on the leeward side of an area

of drift ice.

diverging. Ice fields or floes in an area are subjected to

diverging or dispersive motion, thus reducing ice

concentration and/or relieving stresses in the ice.

dried ice. Sea ice from the surface of which melt-water has

disappeared after the formation of cracks and thaw

holes. During the period of drying, the surface whitens.

drift ice. Term used in a wide sense to include any area of

sea ice, other than fast ice, no matter what form it takes

or how it is disposed. When concentrations are high, ie.

7/10 or more drift ice may be replaced by the term pack

ice.

easy area. A general qualitative expression to indicate, in a

relative manner, that ice conditions prevailing in an area

are such that navigation in it is not difficult.

fast ice. Sea ice which forms and remains fast along the

coast, where it is attached to the shore, to an ice wall, to

Home

Contents

Index

CHAPTER 6

162

an ice front, between shoals or grounded icebergs.

Vertical fluctuations may be observed during changes of

sea level. Fast ice may be formed in situ from sea water

or by freezing of floating ice of any age to the shore,

and it may extend a few metres or several hundred

kilometres from the coast. Fast ice may be more than

one year old and may then be prefixed with the

appropriate age category (old, second-year, or

multi-year). If it is thicker than about 2 m above sea

level it is called an ice shelf. (Photograph 3)

fast-ice boundary. The ice boundary at any given time

between fast ice and drift ice.

fast-ice edge. The demarcation at any given time between

fast ice and open water.

finger rafted ice. Type of rafted ice in which floes thrust

“fingers” alternately over and under the other

(Photograph 26).

finger rafting. Type of rafting whereby interlocking thrusts

are formed, each floe thrusting “fingers” alternately over

and under the other. Common in nilas and grey ice.

firn. Old snow which has crystalised into a dense material.

Unlike ordinary snow, the particles are to some extent

joined together; but, unlike ice, the air spaces in it still

connect with each other.

first-year ice. Sea ice of not more than one winter’s

growth, developing from young ice; thickness

30 centimetres to 2 m. May be sub-divided into thin

first-year ice/white ice medium first-year ice and thick

first-year ice.

flaw. A narrow separation zone between drift ice and fast

ice, where the pieces of ice are in a chaotic state; it

forms when drift ice shears under the effect of a strong

wind or current along the fast-ice boundary. cf.

shearing.

flaw lead. A passage-way between drift ice and fast ice

which is navigable by surface vessels.

flaw polynya. A polynya between drift ice and fast ice.

floating ice. Any form of ice found floating in water. The

principal kinds of floating ice are lake ice, river ice, and

sea ice, which form by the freezing of water at the

surface, and glacier ice (ice of land origin) formed on

land or in an ice shelf. The concept includes ice that is

stranded or grounded.

floe. Any relatively flat piece of sea ice 20 m or more

across. Floes are sub-divided according to horizontal

extent as follows:

Giant Over 10 km across.

Vast 2–10 km across.

Big 500–2000 m across.

Medium 100–500 m across.

Small 20–100 m across.

(Photographs 99, 1010, 1414, & 1919)

floeberg. A massive piece of sea ice composed of a

hummock or a group of hummocks, frozen together and

separated from any ice surroundings. It may protrude up

to 5 m above sea level.

floebit. A relatively small piece of sea ice, normally not

more than 10 m across composed of hummock(s) or part

of ridge(s) frozen together and separated from any

surroundings. It typically protrudes 2 m above sea-level.

flooded ice. Sea ice which has been flooded by melt-water

or river water and is heavily loaded by water and wet

snow.

fracture. Any break or rupture through very close ice,

compact pack ice, consolidated ice, fast ice, or a single

floe resulting from deformation processes. Fractures may

contain brash ice and/or be covered with nilas and/or

young ice. Length may vary from a few metres to many

kilometres:

Large Fracture More than 500 m wide,

Medium Fracture 200–500 m wide,

Small Fracture 50–200 m wide,

Very small Fracture 1–50 m wide,

Crack 0–1 m wide.

fracture zone. An area which has a great number of

fractures.

fracturing. Pressure process whereby ice is permanently

deformed, and ruptures occur. Most commonly used to

describe breaking across very close pack ice, compact

pack ice and consolidated pack ice.

frazil ice. Fine spicules or plates of ice, suspended in

water.

friendly ice. From the point of view of the submariner, an

ice canopy containing many large skylights or other

features which permit a submarine to surface. There

must be more than ten such features per 30 nautical

miles along the submarine’s track.

frost smoke. Fog-like cloud due to contact of cold air with

relatively warm water, which can appear over openings

in the ice, or to leeward of the ice edge, and which may

persist while ice is forming. It often occurs at dawn and

dissipates as the sun rises in the sky (Photograph 4).

giant floe. A floe over 10 km across.

glacier. A mass of snow and ice continuously moving from

higher to lower ground or, if afloat, continuously

spreading. The principal forms of glacier are: inland ice

sheets, ice shelves, ice streams, ice caps, ice piedmonts,

cirque glaciers and various types of mountain (valley)

glaciers.

glacier berg. An irregularly shaped iceberg.

glacier ice. Ice in, or originating from a glacier, whether

on land or floating on the sea as icebergs, bergy bits or

growlers.

glacier tongue. Projecting seaward extension of a glacier,

usually afloat. In the Antarctic glacier tongues may

extend over many tens of kilometres.

grease ice. A later stage of freezing than frazil ice when

the crystals have coagulated to form a soupy layer on

the surface. Grease ice reflects little light, giving the sea

a matt appearance. (Photographs 5 and 6)

grey ice. Young ice 10–15 centimetres thick. Less elastic

than nilas and breaks on swell. Usually rafts under

pressure.

Home

Contents

Index

CHAPTER 6

163

grey-white ice. Young ice 15–30 centimetres thick. Under

pressure more likely to ridge than to raft.

grounded hummock. Hummocked grounded ice formation.

There are single grounded hummocks and lines (or

chains) of grounded hummocks.

grounded ice. Floating ice which is aground in shoal water.

cf. stranded ice.

growler. Rounded pieces of glacier ice smaller than a bergy

bit or floeberg, often transparent but appearing green or

almost black in colour, extending less than 1 m above

the sea surface and normally occupying an area of about

20 square metres (Photographs 6 and 17).

hoarfrost. A deposit of ice having a crystalline appearance,

generally assuming the form of scales, needles, feathers

or fans; produced in a manner similar to dew (ie. by

condensation of water vapour from the air), but at a

temperature below 0°C. (Photograph 15).

hostile ice. From the point of view of the submariner, an

ice canopy containing no large skylights or other

features which permit a submarine to surface.

hummock. A hillock of broken ice which has been forced

upwards by pressure. May be fresh or weathered. The

submerged volume of broken ice under the hummock,

forced downwards by pressure is termed a bummock.

hummocked ice. Sea ice piled haphazardly one piece over

another to form an uneven surface. When weathered, has

the appearance of smooth hillocks.

hummocking. The pressure process by which sea ice is

forced into hummocks. When the floes rotate in the

process it is termed screwing.

iceberg. A massive piece of glacier ice of greatly varying

shape, protruding more than 5 m above sea level, which

has broken away from a glacier, and which may be

afloat or aground. Icebergs may be described as tabular,

dome-shaped, capsized, sloping, pinnacled, weathered or

glacier bergs. (Photographs 7 and 8). See also 6.19.

iceberg tongue. A major accumulation of icebergs

projecting from the coast, held in place by grounding

and joined together by fast ice.

ice blink. A whitish glare on low clouds above an

accumulation of distant ice. (Photograph 18)

ice-bound. A harbour, inlet, or similar expanse of water is

said to be ice-bound when navigation by ships is

prevented on account of ice, except possibly with the

assistance of an ice-breaker.

ice boundary. The demarcation at any given time between

fast ice and drift ice or between areas of drift ice of

different concentrations.

ice breccia. Ice pieces of different stages of development

frozen together.

ice cake. Any relatively flat piece of sea ice less than 20 m

across. (Photograph 19)

ice canopy. Drift ice from the point of view of the

submariner.

ice cover. The ratio of an area of ice of any concentration

to the total area of sea surface within some large

geographical locale; this locale may be global,

hemispheric, or prescribed by a specific oceanographic

entity such as Baffin Bay or the Barents Sea.

ice edge. The demarcation at any given time between the

open sea and sea ice of any kind, whether fast or

drifting. It may be termed compacted or diffuse. cf. ice

boundary. (Photograph 20)

ice field. Area of floating ice consisting of any size of

floes, which is greater than 10 km across. cf. ice patch

icefoot. A narrow fringe of ice attached to the coast,

unmoved by tides and remaining after the fast ice has

moved away.

ice-free. No ice present. If ice of any kind is present this

term should not be used.

ice front. The vertical cliff forming the seaward face of an

ice shelf or other floating glacier varying in height from

2–50 m or more above sea level. cf. ice wall.

(Photograph 21)

ice island. A large piece of floating ice protruding about

5 m above sea level, which has broken away from an

Arctic ice shelf, having a thickness of 30–50 m and an

area of from a few thousand square metres to 500 sq km

or more, and usually characterized by a regularly

undulating surface which gives it a ribbed appearance

from the air. (Photograph 22)

ice isthmus. A narrow connection between two ice areas of

very close or compact ice. It may be difficult to pass,

whilst sometimes being part of a recommended route.

ice jam. An accumulation of broken river ice or sea ice

caught in a narrow channel.

ice keel. From the point of view of the submariner, a

downward-projecting ridge on the underside of the ice

canopy; the counterpart of a ridge. Ice keels may extend

as much as 50 m below sea level.

ice limit. Climatological term referring to the extreme

minimum or extreme maximum extent of the ice edge in

any given month or period based on observations over a

number of years. Terms should be preceded by minimum

or maximum. cf. mean ice edge.

ice massif. A variable accumulation of close or very close

ice covering hundreds of square kilometres which is

found in the same region every summer.

ice of land origin. Ice formed on land or from an ice

shelf, found floating in water. The concept includes ice

that is stranded or grounded.

ice patch. An area of floating ice less than 10 km across.

ice piedmont. Ice covering a coastal strip of low-lying land

backed by mountains. The surface of an ice piedmont

slopes gently seaward and may be anything from about

1 cable to 30 miles wide, fringing long stretches of

coastline with ice cliffs known as ice walls. Ice

piedmonts frequently merge into ice shelves.

ice port. An embayment in an ice front, often of a

temporary nature, where ships can moor alongside and

unload directly onto the ice shelf. (Photograph 23)

ice rind. A brittle shiny crust of ice formed on a quiet

surface by direct freezing or from grease ice, usually in

water of low salinity. Thickness to about 5 centimetres.

Easily broken by wind or swell, commonly breaking in

rectangular pieces. (Photograph 15)

Home

Contents

Index

CHAPTER 6

164

ice shelf. A floating ice sheet of considerable thickness

showing 2–50 m or more above sea level, attached to

the coast. Usually of great horizontal extent and with a

level or gently undulating surface. Nourished by annual

snow accumulation and often also by the seaward

extension of land glaciers. Limited areas may be

aground. The seaward edge is termed an ice front.

(Photograph 3)

ice stream. Part of an inland ice sheet in which the ice

flows more rapidly and not necessarily in the same

direction as the surrounding ice. The margins are

sometimes clearly marked by a change in direction of

the surface slope but may be indistinct.

ice under pressure. Ice in which deformation processes are

actively occurring and hence a potential impediment or

danger to shipping.

ice wall. An ice cliff forming the seaward margin of a

glacier which is not afloat. An ice wall is aground, the

rock basement being at or below sea level.

(Photograph 24)

jammed brash barrier. A strip or narrow belt of new,

young or brash ice (usually 100–5000 m wide) formed at

the edge of either drift or fast ice or at the shore. It is

heavily compacted mostly due to wind action and may

extend 2–20 m below the surface but does not normally

have appreciable topography. Jammed brash barrier may

disperse with changing winds but can only consolidate

to form a strip of unusually thick ice in comparison with

the surrounding drift ice.

lake ice. Ice formed on a lake, regardless of observed

location.

large fracture. More than 500 m wide.

large ice field. An ice field over 20 km across.

lead. Any fracture or passage-way through sea ice which is

navigable by surface vessels. (Photograph 25)

level ice. Sea ice which has not been affected by

deformation.

light nilas. Nilas which is more than 5 centimetres in

thickness and rather lighter in colour than dark nilas.

(Photograph 26)

mean ice edge. Average position of the ice edge in any

given month or period based on observations over a

number of years. Other terms which may be used are

mean maximum ice edge and mean minimum ice edge,

cf. ice limit.

medium first-year ice. First-year ice 70–120 centimetres

thick.

medium floe. A floe 100–500 m across.

medium fracture. A fracture 200–500 m wide.

medium ice field. An ice field 15–20 km across.

moraine. Ridges or deposits of rock debris transported by

a glacier. Common forms are: ground moraine, formed

under a glacier; lateral moraine, along the sides; medial

moraine, down the centre; and end moraine, deposited at

the foot. Moraines are left after a glacier has receded,

providing evidence of its former extent.

multi-year ice. Old ice up to 3 m or more thick which has

survived at least two summers’ melt. Hummocks even

smoother than in second-year ice, and the ice is almost

salt free. Colour, where bare, is usually blue. Melt

pattern consists of large interconnecting irregular puddles

and a well-developed drainage system.

new ice. A general term for recently formed ice which

includes frazil ice, grease ice, slush and shuga. These

types of ice are composed of ice crystals which are only

weakly frozen together (if at all) and have a definite

form only while they are afloat.

new ridge. Ridge newly formed with sharp peaks and

slope of sides usually 40°. Fragments are visible from

the air at low altitude.

nilas. A thin elastic crust of ice, easily bending on waves

and swell and under pressure, thrusting in a pattern of

interlocking “fingers” (finger rafting). Has a matt surface

and is up to 10 centimetres in thickness. May be

sub-divided into dark nilas and light nilas.

(Photograph 26)

nip. Ice is said to nip when it forcibly presses against a

ship. A vessel so caught, though undamaged, is said to

have been nipped.

nunatak. A rocky crag or small mountain projecting from

and surrounded by a glacier or ice sheet.

old ice. Sea ice which has survived at least one summer’s

melt; typical thickness up to 3 m or more. Most

topographic features are smoother than on first-year ice.

May be sub-divided into second-year ice and multi-year

ice. (Photograph 27)

open ice. Floating ice in which the ice concentration is

4/10–6/10, with many leads and polynyas, and the floes

are generally not in contact with one another.

(Photograph 9)

open water. A large area of freely navigable water in

which sea ice is present in concentrations less than 1/10.

No ice of land origin is present.

pack ice. See drift ice. The term was formerly for all

ranges of concentration.

pancake ice. Predominantly circular pieces of ice from

30 centimetres to 3 m in diameter, and up to about

10 centimetres in thickness, with raised rims due to the

pieces striking against one another. It may be formed on

a slight swell from grease ice, shuga or slush or as a

result of the breaking of ice rind, nilas or, under severe

conditions of swell or waves, of grey ice. It also

sometimes forms at some depth, at an interface between

water bodies of different physical characteristics, from

where it floats to the surface; its appearance may rapidly

cover wide areas of water. (Photograph 13)

pingo. A mound formed by the upheaval of subterranean

ice in an area where the subsoil remains permanently

frozen.

Pingos are also found in Arctic waters, rising about

30 m from an otherwise even seabed, with bases

about 40 m in diameter and surrounded by a

shallow moat; they are then termed submarine

pingos.

Oceanographically, a more or less conical mound of

fine unconsolidated material characteristically

containing an ice core.

Home

Contents

Index

CHAPTER 6

165

polynya. Any non-linear shaped opening enclosed in drift

ice. Polynyas may contain brash ice and/or be covered

with new ice, nilas or young ice.

puddle. An accumulation on ice of melt-water, mainly due

to melting snow, but in the more advanced stages also

due to the melting of ice. Initial stage consists of

patches of melted snow on an ice floe.

rafted ice. Type of deformed ice formed by one piece of

ice overriding another, cf. finger rafting.

rafting. Pressure processes whereby one piece of ice

overrides another. Most common in new and young ice,

cf. finger rafting.

ram. An underwater ice projection from an ice wall, ice

front, iceberg or floe. Its formation is usually due to a

more intense melting and erosion of the unsubmerged

part. (Photograph 14)

recurring polynya. A polynya which recurs in the same

position every year.

ridge. A line or wall of broken ice forced up by pressure.

May be fresh or weathered. The submerged volume of

broken ice under a ridge, forced downwards by pressure

is termed an ice keel.

ridged ice. Ice piled haphazardly one piece over another in

the form of ridges or walls. Usually found in first-year

ice, cf. ridging.

ridged ice zone. An area in which much ridged ice with

similar characteristics has formed.

ridging. The pressure process by which sea ice is forced

into ridges.

rime. A deposit of ice composed of grains more or less

separated by trapped air, some adorned with crystalline

branches, produced by the rapid freezing of super-cooled

and very small water droplets.

river ice. Ice formed on a river, regardless of observed

location.

rotten ice. Sea ice which has become honey-combed and

which is in an advanced state of disintegration.

rubble field. An area of extremely deformed sea ice of

unusual thickness formed during the winter by the

motion of drift ice against, or around a protruding rock,

islet, or other obstruction.

sastrugi. Sharp, irregular ridges formed on a snowy surface

by wind erosion and deposition. On drift ice the ridges

are parallel to the direction of the prevailing wind at the

time they were formed. (Photograph 16)

screwing. See Hummocking.

sea ice. Any form of ice found at sea which has originated

from the freezing of sea water, as opposed to ice of land

origin.

second-year ice. Old ice which has survived only one

summer’s melt; typical thickness up to 2·5 m and

sometimes more. Because it is thicker than first-year ice,

it stands higher out of the water. In contrast to

multi-year ice, summer melting produces a regular

pattern of numerous small puddles. Bare patches and

puddles are usually greenish-blue.

shearing. An area of drift ice is subject to shear when the

ice motion varies significantly in the direction normal to

the motion, subjecting the ice to rotational forces. These

forces may result in phenomena similar to a flaw (qv).

shear ridge. An ice ridge formation which develops when

one ice feature is grinding past another. The type of

ridge is more linear than those caused by pressure alone.

shear ridge field. Many shear ridges side by side.

shore lead. A lead between drift ice and the shore or

between drift ice and an ice front.

shore ice ride-up. A process by which ice is pushed

ashore as a slab.

shore polynya. A polynya between drift ice and the coast

or between drift ice and an ice front.

shore melt. Open water between the shore and the fast ice,

formed by melting and/or as a result of river discharge.

shuga. An accumulation of spongy white ice lumps, a few

centimetres across; they are formed from grease ice or

slush and sometimes from anchor ice rising to the

surface. (Photographs 6 and 17)

skylight. From the point of view of the submarine, thin

places in the ice canopy, usually less than 1 m thick and

appearing from below as relatively light, translucent

patches in dark surroundings. The undersurface of a

skylight is normally flat. Skylights are called large if big

enough for a submarine to attempt to surface through

them (120 m) or small if not.

slush. Snow which is saturated and mixed with water on

land or ice surfaces, or as a viscous floating mass in

water after a heavy snowfall.

small floe. A floe 20–100 m across.

small fracture. A fracture 50–200 m wide.

small ice cake. An ice cake less than 2 m across.

small ice field. An ice field 10–15 km across.

snow barchan. See snowdrift.

snowdrift. An accumulation of wind-blown snow deposited

in the lee of obstructions or heaped by wind eddies. A

crescent-shaped snowdrift, with ends pointing downwind,

is known as a snow barchan.

standing floe. A separate floe standing vertically or

inclined and enclosed by rather smooth ice.

stranded ice. Ice which has been floating and has been

deposited on the shore by retreating high water.

strip. Long narrow area of floating ice, about 1 km or less

in width, usually composed of small fragments detached

from the main mass of ice, and run together under the

influence of wind, swell or current.

submarine pingo. See pingo.

tabular berg. A flat-topped iceberg. Most tabular bergs

form by calving from an ice shelf and show horizontal

banding, cf. ice island. (Photograph 22)

thaw holes. Vertical holes in sea ice formed when surface

puddles melt through to the underlying water.

thick first-year ice. First-year ice over 120 centimetres

thick.

Home

Contents

Index

CHAPTER 6

166

thick first-year ice/white ice. First-year ice

30–70 centimetres thick.

thin first-year ice/white ice first stage, 30–50 centimetres

thick

thin first-year ice/white ice second stage,

50–70 centimetres thick

tide crack. Crack at the line of junction between an

immovable ice foot or ice wall and fast ice, the latter

subject to rise and fall of the tide.

tongue. A projection of the ice edge up to several

kilometres in length, caused by wind or current.

vast floe. A floe 2–10 km across.

very close ice. Floating ice in which the concentration is

9/10 to less than 10/10 (Photograph 11).

very open ice. Floating ice in which the concentration is

1/10 to 3/10 and water preponderates over ice.

(Photograph 14)

very small fracture. A fracture 1–50 m wide.

very weathered ridge. Ridge with tops very rounded, slope

of sides usually 20°–30°.

water sky. Dark streaks on the underside of low clouds,

indicating the presence of water features in the vicinity

of sea ice.

weathered ridge. Ridge with peaks slightly rounded and

slope of sides usually 30°–40°. Individual fragments are

not discernible.

weathering. Processes of ablation and accumulation which

gradually eliminate irregularities in an ice surface.

white ice. See thin first-year ice.

young coastal ice. The initial stage of fast ice formation

consisting of nilas or young ice, its width varying from

a few metres up to 100–200 m from the shoreline.

young ice. Ice in the transition stage between nilas and

first-year ice, 10–30 centimetres in thickness. May be

sub-divided into grey ice and grey-white ice.

Ice Terms arranged by subject

6.28

Floating ice:

The principal kinds are: Sea ice, Lake ice, River ice

and Ice of land origin.

Development:

New ice: includes Frazil ice, Grease ice

(Photographs 5 and 6), Slush and Shuga

(Photographs 6 and 17);

Nilas: may be sub-divided into Dark and Light Nilas

(Photograph 26) and Ice Rind (Photograph 15);

Pancake ice (Photograph 13);

Young ice: Grey or Grey-white ice;

First-year ice: may be designed Thin/White, Medium

or Thick;

Old ice: may be sub-divided into Second-year ice or

Multi-year ice.

Forms of Fast ice:

Fast ice (Photograph 3): called Young Coastal ice in

its initial stage;

Icefoot;

Anchor ice;

Grounded ice: includes Stranded ice and Grounded

hummock.

Drift ice:

Ice cover;

Concentration: may be designated Compact,

Consolidated (Photograph 12),

Very Close (Photograph 11),

Close (Photograph 10),

Open (Photograph 9), or

Very Open ice (Photograph 14),

Open water, Bergy water or Ice-free.

Forms of Floating ice: include

Pancake ice (Photograph 13),

Floe (Photograph 19),

Ice cake (Photograph 19),

Floeberg, Floebit, Ice Breccia, Brash ice

(Photograph 2),

Iceberg (Photographs 7 and 8),

Glacier berg, Tabular berg (Photograph 7),

Ice Island (Photograph 22),

Bergy bit (Photograph 1) and

Growler (Photograph 6);

Arrangement: see Ice Field, Ice Isthmus, Ice Massif,

Belt, Tongue, Strip, Bight, Rubble Field, Shear

Ridge Field, Ice Jam, Ice Edge (Photograph 20),

Ice Boundary, Iceberg Tongue.

Drift Ice motion processes:

Diverging;

Compacting;

Shearing

Deformation processes:

Fracturing;

Hummocking;

Ridging;

Rafting;

Shore ice ride-up;

Weathering.

Openings in the ice:

Fracture: see also Crack, Tide Crack and Flaw;

Fracture zone;

Lead (Photograph 25);

Polynya; includes Shore polynya, Flaw polynya and

Recurring polynya.

Ice-surface features:

Level ice;

Deformed ice: sub-divisions include: Rafted ice Ridge

and Hummock;

Standing floe;

Ram (Photograph 14);

Bare ice;

Snow-covered ice: includes Sastrugi (Photograph 16)

and Snowdrift.

Stages of melting:

Puddle;

Thaw holes;

Dried ice;

Rotten ice;

Flooded ice;

Shore melt.

Ice of land origin:

Firn;

Glacier ice: (see also Glacier), Ice Wall

(Photograph 24), Ice Stream and Glacier Tongue;

Home

Contents

Index

CHAPTER 6

167

Ice shelf: the seaward edge is termed an Ice Front

(Photograph 21);

Calved ice: see Iceberg, Ice Island, Bergy bit and

Growler.

Sky and air indications:

Water sky;

Ice blink (Photograph 18);

Frost smoke (Photograph 4).

Terms relating to surface shipping:

Area of weakness;

Beset;

Ice bound;

Nip;

Ice under pressure;

Difficult area;

Easy area;

Iceport.

Terms relaying to submarine navigation:

Ice canopy;

Friendly ice;

Hostile ice;

Bummock;

Ice keel;

Skylight.

Home

Contents

Index

168

CHAPTER 7

OPERATIONS IN POLAR REGIONS AND WHERE ICE IS PREVALENT

POLAR REGIONS

The polar environment

7.1

1 In high latitudes, directions change fast with movement

of the observer. Near the poles, meridians converge, and

excessive longitudinal curvature renders the meridians and

parallels impracticable for use as navigational references.

All time zones meet at the poles, and local time has little

significance. Sunrise and sunset, night and day, as they are

known in the temperate regions, are quite different in polar

regions.

2 At the poles the sun rises and sets once a year, slowly

spiralling for three months to a maximum altitude of 23°27′

and then decreasing in altitude until it sets again three

months later. The Moon rises once each month and

provides illumination when full, though sometimes the

aurora gives even more light; and the planets rise and set

once each sidereal period (12 years for Jupiter, 30 years for

Saturn).

3 Fog is most frequent when the water is partly clear of

ice. Low cloud ceilings are prevalent. “Whiteouts” occur

from time to time, when daylight is diffused by multiple

reflection between a snow surface and an overcast sky, so

that contrasts vanish and neither the horizon nor surface

features can be distinguished. All these conditions,

combined with the ice itself, add to the difficulties of

navigation.

Charts

7.2

1 Polar charts are based largely on aerial photography

which may be without proper ground control, except in a

relatively few places where modern surveys are available,

eg in the approaches to bases and similar frequented

localities. Even then, the conditions under which these

surveys have been carried out are such that their accuracy

is unlikely to be similar to that of work done in more

clement climes. For these reasons the geographical

positions of features may be unreliable and, even when

they are correctly placed relative to adjacent features,

considerable errors may accumulate when they are

separated by appreciable distances. In general, soundings,

topography and all navigational information are sparse in

most polar regions.

2 Visual and radar bearings, unless of observed objects

which are close, require to be treated as great circles. If

used on a Mercator chart, bearings should be corrected for

half-convergency in the same way as radio bearings. See

Admiralty List of Radio Signals Volume 2.

3 Natural landmarks are plentiful in some areas, but their

usefulness is restricted by the difficulty in identifying them,

or locating them on the chart. Along many of these coasts

the various points and inlets bear a marked resemblance to

each other. The appearance of a coast is often very

different when many of its features are masked by a heavy

covering of snow or ice than when it is ice-free.

Compasses

7.3

1 The gyro compass loses all horizontal directive force as

the poles are approached and is thought to become useless

at about 85° of latitude. It is generally reliable up to 70°

but thereafter should be checked by azimuths of celestial

bodies at frequent intervals (about every 4 hours and more

frequently in higher latitudes). Frequent changes of course

and speed and the impact of the vessel on ice introduce

errors which are slow to settle out.

2 The magnetic compass is of little value for navigation

near the magnetic poles. Large diurnal changes in variation

(as much as 10°), attributed to the continual motion of the

poles, have been reported.

In other parts of the polar regions, however, the

magnetic compass can be used, provided that the ship has

been swung and the compass adjusted in low latitudes, and

again on entering high ones.

3 Frequent comparisons of magnetic and gyro compasses

should be made and logged when azimuth checks are

obtained.

Sounders

7.4

1 The echo sounder should be run continuously to detect

signs of approaching shoal water, though in many parts of

the polar regions depths change too abruptly to enable the

mariner to rely solely on the sounder for warning.

In some better sounded areas, the depths may give an

indication of the ship’s position, or of the drift of the ice,

and in these areas ships should make use of all enforced

stops to obtain a sounding.

2 Working in drift ice the echo sounder trace may be lost

due to ice under the ship or hull noises, so, if necessary,

the ship should be slowed to obtain a sounding.

Sights

7.5

1 The mariner cannot rely on obtaining accurate celestial

observations. For much of the navigational season clouds

hide the sun, and long days and short nights in summer

preclude the use of stars for observations. In summer when,

apart from the moon at times, only the sun can be used for

observations, transferred position lines must be used, and as

accurate dead reckoning in ice is impossible, the accuracy

of the resulting positions must always be questioned.

2 The best positions are usually obtained from star

observations during twilight. As the latitude increases

twilights lengthen, but with this increase come longer

periods when the sun is just below the horizon and the

stars have not yet appeared.

In polar regions the only celestial body available for

observations may not exceed the altitude of 10° for several

weeks on end, so that, contrary to the usual practice,

observations at low altitudes must be accepted.

3 Most celestial observations in polar regions produce

satisfactory results, but in high latitudes the navigator

should be on the alert for abnormal conditions.

Radio aids and electronic position-fixing systems

7.6

1 Radar will be found a most valuable instrument for safe

navigation if used judiciously. It should not be relied upon

so completely that the rules of good seamanship are

relaxed.

Electronic Position-fixing systems, when available, are as

satisfactory in polar regions as in other parts of the world.

Home

Contents

Index

CHAPTER 7

169

APPROACHING ICE

Readiness for ice

7.7

1 Experience has shown that ships that are not

ice-strengthened and with a speed in open water of about

12 kn often become firmly beset in light ice conditions,

whereas an adequately powered ice-strengthened ship

should be able to make progress through 6/10 to 7/10

first-year ice.

2 The engines and steering gear of any ship intending to

operate in ice must be reliable and capable of quick

response to manoeuvring orders. The navigational and

communications equipment must be equally reliable and

particular attention should be paid to maintaining radar at

peak performance.

3 Ships operating in ice should be ballasted and trimmed

so that the propeller is completely submerged and as deep

as possible, but without excessive stern trim which reduces

manoeuvrability. If the tips of the propeller are exposed

above the surface or just under the surface, the risk of

damage due to the propeller striking ice is greatly

increased.

4 Ballast and fresh water tanks should be kept not more

than 90% full to avoid risk of damage to them from

expansion if the water freezes.

Good searchlights should be available for night

navigation, with or without icebreaker escort.

Signs of icebergs

7.8

1 Caution. There are no infallible signs of the proximity

of an iceberg. Complete reliance on radar or any of the

possible signs can be dangerous. The only sure way is to

see it.

7.9

1 Unreliable signs. Changes of air or sea temperature

cannot be relied upon to indicate the vicinity of an iceberg.

However, the sea temperature, if carefully watched, will

indicate when the cold ice-bearing current is entered.

Echoes from a steam whistle or siren are also unreliable

because the shape of the iceberg may be such as to prevent

any echo, and also because echoes are often obtained from

fog banks.

2 Sonar has been used to locate icebergs, but the method

is unreliable since the distribution of water temperature and

salinity, particularly near the boundary of a current, may

produce such excessive refraction as to prevent a sonar

signal from reaching the vessel or iceberg.

7.10

1 Likely signs. The following signs are useful when they

occur, but reliability cannot be placed on their occurrence.

In the case of large Antarctic icebergs, the absence of

sea in a fresh breeze indicates the presence of ice to

windward if far from the land.

When icebergs calve, or ice otherwise cracks and falls

into the sea, it produces a thunderous roar, or sounds like

the distant discharge of guns.

2 The observation of growlers (Photograph 6, page 149) or

smaller pieces of brash ice is an indication that an iceberg

is in the vicinity, and probably to windward; an iceberg

may be detected in thick fog by this means.

When proceeding at slow speed on a quiet night, the

sound of breakers may be heard if an iceberg is near and

should be constantly listened for.

7.11

1 Visibility of icebergs. Despite their size, icebergs can be

very difficult to see under certain circumstances, and the

mariner should invariably navigate with caution in waters

in which they may be expected.

In fog with sun shining an iceberg appears as a

luminous white mass, but with no sun it appears close

aboard as a dark mass, and the first signs may well be the

wash of the sea breaking on its base.

2 On a clear night with no moon icebergs may be sighted

at a distance of 1 or 2 miles, appearing as black or white

objects, but the ship may then be among the bergy bits

(Photograph 1, page 147) and growlers often found in the

vicinity of an iceberg. On a clear night, therefore, lookouts

and radar operators should be particularly alert, and there

should be no hesitation in reducing speed if an iceberg is

sighted without warning.

3 On moonlit nights icebergs are more easily seen

provided the moon is behind the observer, particularly if it

is high and full.

At night with a cloudy sky and intermittent moonlight,

icebergs are more difficult to see and to keep in sight.

Cumulus or cumulonimbus clouds at night can produce a

false impression of icebergs.

Signs of drift ice

7.12

1 There are two reliable signs of drift ice.

Ice Blink (Photograph 18, page 155) whose characteristic

light effects in the sky once seen, can never be mistaken, is

one of these signs. On clear days, with the sky mostly

blue, ice blink appears as a luminous yellow haze on the

horizon in the direction of the ice. It is brighter below, and

shades off upward, its height depending on the proximity

of the ice field. On days with overcast sky, or low clouds,

the yellow colour is almost absent, the ice blink appearing

as a whitish glare on the clouds. Under certain conditions

of sun and sky, both the yellowish and whitish glares may

be seen simultaneously. It may sometimes be seen at night.

2 Ice blink is observed some time before the ice itself

appears over the horizon. It is rarely, if ever, produced by

icebergs, but is always distinct over consolidated and

extensive pack.

In fog white patches indicate the presence of ice at a

short distance.

Abrupt smoothing of the sea and the gradual lessening

of the ordinary ocean swell is the other reliable sign, and a

sure indication of drift ice to windward.

3 Isolated fragments of ice often point to the proximity of

larger quantities.

There is frequently a thick band of fog over the edge of

drift ice. In fog, white patches indicate the presence of ice

at a short distance.

In the Arctic, if far from land, the appearance of

walruses, seals and birds may indicate the proximity of ice.

In the Antarctic, the Antarctic Petrel and Snow Petrel

are said to indicate the proximity of ice — the former

being found only within 400 miles of the ice edge, and the

latter considerably closer to it.

4 Sea surface temperatures give little or no indication of

the near vicinity of ice. When, however, the surface

temperature falls to +1°C, and the ship is not within one of

the main cold currents, the ice edge should for safety be

considered as not more than 150 miles distant, or 100 miles

if there is a persistent wind blowing off the ice, since this

will cause the ice temporarily to extend and become more

open. A surface temperature of –0·5°C should generally be

assumed to indicate that the nearest ice is not more than

50 miles away.

Home

Contents

Index