Nigel S., Chambers S., Johnson R. Operations Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Responding to the criticisms of EOQ

In order to keep EOQ-type models relatively straightforward, it was necessary to make

assumptions. These concerned such things as the stability of demand, the existence of a fixed

and identifiable ordering cost, that the cost of stock holding can be expressed by a linear

function, shortage costs which were identifiable, and so on. While these assumptions are rarely

strictly true, most of them can approximate to reality. Furthermore, the shape of the total cost

curve has a relatively flat optimum point which means that small errors will not significantly

affect the total cost of a near-optimum order quantity. However, at times the assumptions

do pose severe limitations to the models. For example, the assumption of steady demand

(or even demand which conforms to some known probability distribution) is untrue for a

wide range of the operation’s inventory problems. For example, a bookseller might be very

happy to adopt an EOQ-type ordering policy for some of its most regular and stable pro-

ducts such as dictionaries and popular reference books. However, the demand patterns for

many other books could be highly erratic, dependent on critics’ reviews and word-of-mouth

recommendations. In such circumstances it is simply inappropriate to use EOQ models.

Cost of stock

Other questions surround some of the assumptions made concerning the nature of stock-

related costs. For example, placing an order with a supplier as part of a regular and multi-item

order might be relatively inexpensive, whereas asking for a special one-off delivery of an item

Part Three Planning and control

354

D = 80,000 per month

= 500 per hour

EBQ =

=

EBQ = 13,856

The staff who operate the lines have devised a method of reducing the changeover time

from 1 hour to 30 minutes. How would that change the EBQ?

New C

o

= £50

New EBQ =

= 9,798

2 × 50 × 80,000

0.1(1 − (500/3,000))

2 × 100 × 80,000

0.1(1 − (500/3,000))

2C

o

D

C

h

(1 − (D/P))

The approach to determining order quantity which involves optimizing costs of holding stock

against costs of ordering stock, typified by the EOQ and EBQ models, has always been

subject to criticisms. Originally these concerned the validity of some of the assumptions

of the model; more recently they have involved the underlying rationale of the approach

itself. The criticisms fall into four broad categories, all of which we shall examine further:

● The assumptions included in the EOQ models are simplistic.

● The real costs of stock in operations are not as assumed in EOQ models.

● The models are really descriptive, and should not be used as prescriptive devices.

● Cost minimization is not an appropriate objective for inventory management.

Critical commentary

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 354

could prove far more costly. Similarly with stock-holding costs – although many companies

make a standard percentage charge on the purchase price of stock items, this might not be

appropriate over a wide range of stock-holding levels. The marginal costs of increasing stock-

holding levels might be merely the cost of the working capital involved. On the other hand,

it might necessitate the construction or lease of a whole new stock-holding facility such as a

warehouse. Operations managers using an EOQ-type approach must check that the decisions

implied by the use of the formulae do not exceed the boundaries within which the cost

assumptions apply. In Chapter 15 we explore the just-in-time approach which sees inventory

as being largely negative. However, it is useful at this stage to examine the effect on an EOQ

approach of regarding inventory as being more costly than previously believed. Increasing

the slope of the holding cost line increases the level of total costs of any order quantity, but

more significantly, shifts the minimum cost point substantially to the left, in favour of a lower

economic order quantity. In other words, the less willing an operation is to hold stock on the

grounds of cost, the more it should move towards smaller, more frequent ordering.

Using EOQ models as prescriptions

Perhaps the most fundamental criticism of the EOQ approach again comes from the

Japanese-inspired ‘lean’ and JIT philosophies. The EOQ tries to optimize order decisions.

Implicitly the costs involved are taken as fixed, in the sense that the task of operations

managers is to find out what are the true costs rather than to change them in any way. EOQ

is essentially a reactive approach. Some critics would argue that it fails to ask the right

question. Rather than asking the EOQ question of ‘What is the optimum order quantity?’,

operations managers should really be asking, ‘How can I change the operation in some way

so as to reduce the overall level of inventory I need to hold?’ The EOQ approach may be a

reasonable description of stock-holding costs but should not necessarily be taken as a strict

prescription over what decisions to take. For example, many organizations have made con-

siderable efforts to reduce the effective cost of placing an order. Often they have done this

by working to reduce changeover times on machines. This means that less time is taken

changing over from one product to the other, and therefore less operating capacity is lost,

which in turn reduces the cost of the changeover. Under these circumstances, the order

cost curve in the EOQ formula reduces and, in turn, reduces the effective economic order

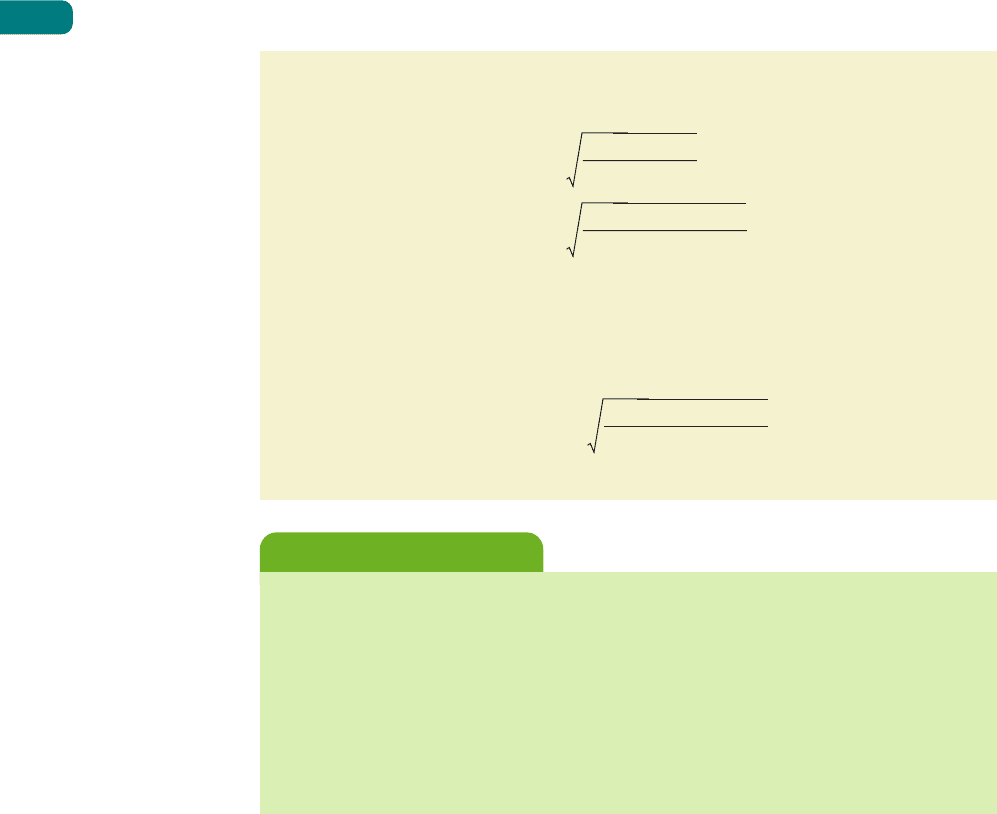

quantity. Figure 12.9 shows the EOQ formula represented graphically with increased hold-

ing costs (see the previous discussion) and reduced order costs. The net effect of this is to

significantly reduce the value of the EOQ.

Should the cost of inventory be minimized?

Many organizations (such as supermarkets and wholesalers) make most of their revenue

and profits simply by holding and supplying inventory. Because their main investment is

in the inventory it is critical that they make a good return on this capital, by ensuring that

it has the highest possible ‘stock turn’ (defined later in this chapter) and/or gross profit

margin. Alternatively, they may also be concerned to maximize the use of space by seeking

to maximize the profit earned per square metre. The EOQ model does not address these

objectives. Similarly for products that deteriorate or go out of fashion, the EOQ model can

result in excess inventory of slower-moving items. In fact, the EOQ model is rarely used in

such organizations, and there is more likely to be a system of periodic review (described later)

for regular ordering of replenishment inventory. For example, a typical builders’ supply

merchant might carry around 50,000 different items of stock (SKUs – stock-keeping units).

However, most of these cluster into larger families of items such as paints, sanitaryware or

metal fixings. Single orders are placed at regular intervals for all the required replenishments

in the supplier’s range, and these are then delivered together at one time. For example,

if such deliveries were made weekly, then on average, the individual item order quantities

will be for only one week’s usage. Less popular items, or ones with erratic demand patterns,

can be individually ordered at the same time, or (when urgent) can be delivered the next

day by carrier.

Chapter 12 Inventory planning and control

355

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 355

Part Three Planning and control

356

Figure 12.9 If the true costs of stock holding are taken into account, and if the cost of

ordering (or changeover) is reduced, the economic order quantity (EOQ) is much smaller

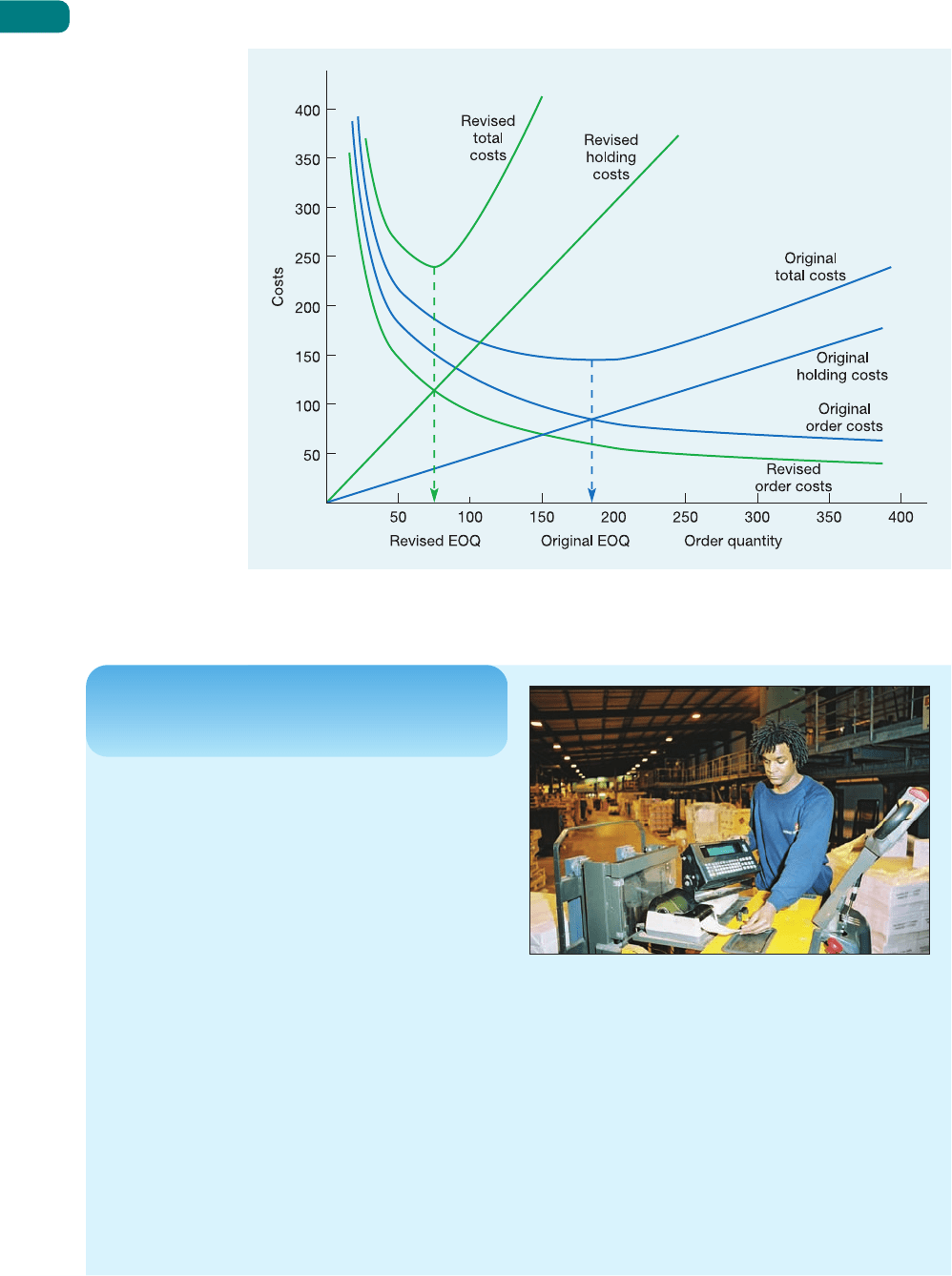

The Howard Smith Paper Group operates the most

advanced warehousing operation within the European

paper merchanting sector, delivering over 120,000 tonnes

of paper annually. The function of a paper merchant is to

provide the link between the paper mills and the printers

or converters. This is illustrated in Figure 12.10. It is a

sales- and service-driven business, so the role of the

operation function is to deliver whatever the salesperson

has promised to the customer. Usually, this means

precisely the right product at the right time at the right

place and in the right quantity. The company’s operations

are divided into two areas, ‘logistics’ which combines

all warehousing and logistics tasks, and ‘supply side’

which includes inventory planning, purchasing and

merchandizing decisions. Its main stocks are held at

the national distribution centre, located in Northampton

in the middle part of the UK. This location was chosen

because it is at the centre of the company’s main

customer location and also because it has good access

to motorways. The key to any efficient merchanting

operation lies in its ability to do three things well.

First, it must efficiently store the desired volume of

required inventory. Second, it must have a ‘goods

Short case

Howard Smith Paper Group

2

inward’ programme that sources the required volume

of desired inventory. Third, it must be able to fulfil

customer orders by ‘picking’ the desired goods fast

and accurately from its warehouse. The warehouse is

operational 24 hours per day, 5 days per week. A total

of 52 staff are employed in the warehouse, including

maintenance and cleaning staff. Skill sets are not an

issue, since all pickers are trained for all tasks. This

facilitates easier capacity management, since pickers

can be deployed where most urgently needed. Contract

labour is used on occasions, although this is less

Source: Howard Smith Paper Group

Dispatch activity at Howard Smith Paper Group

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 356

Chapter 12 Inventory planning and control

357

effective because the staff tend to be less motivated,

and have to learn the job.

At the heart of the company’s operations is a

warehouse known as a ‘dark warehouse’. All picking and

movement within the dark warehouse is fully automatic

and there is no need for any person to enter the high-bay

stores and picking area. The important difference with this

warehouse operation is that pallets are brought to the

pickers. Conventional paper merchants send pickers with

handling equipment into the warehouse aisles for stock.

A warehouse computer system (WCS) controls the whole

operation without the need for human input. It manages

pallet location and retrieval, robotic crane missions,

automatic conveyors, bar-code label production and

scanning, and all picking routines and priorities. It also

calculates operator activity and productivity measures,

as well as issuing documentation and planning

transportation schedules. The fact that all products are

identified by a unique bar code means that accuracy is

guaranteed. The unique user log-on ensures that any

picking errors can be traced back to the name of the

picker, to ensure further errors do not occur. The WCS

is linked to the company’s ERP system (we will deal with

ERP in Chapter 14), such that once the order has been

placed by a customer, computers manage the whole

process from order placement to order dispatch.

Figure 12.10 The role of the paper merchant

The timing decision – when to place an order

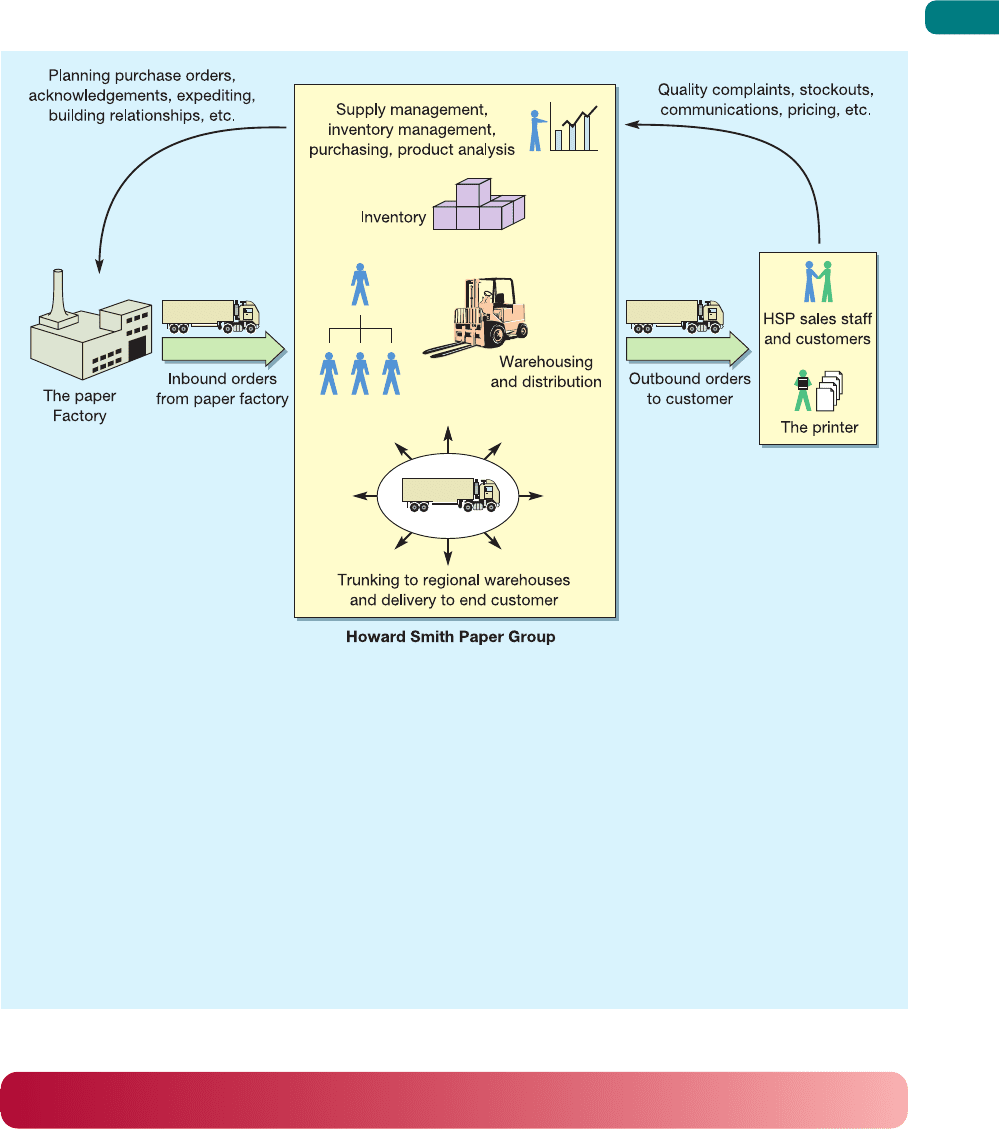

When we assumed that orders arrived instantaneously and demand was steady and predict-

able, the decision on when to place a replenishment order was self-evident. An order would be

placed as soon as the stock level reached zero. This would arrive instantaneously and prevent

any stock-out occurring. If replenishment orders do not arrive instantaneously, but have

a lag between the order being placed and it arriving in the inventory, we can calculate the

timing of a replacement order as shown in Figure 12.11. The lead time for an order to arrive

is in this case two weeks, so the re-order point (ROP) is the point at which stock will fall to

zero minus the order lead time. Alternatively, we can define the point in terms of the level

Re-order point

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 357

which the inventory will have reached when a replenishment order needs to be placed. In this

case this occurs at a re-order level (ROL) of 200 items.

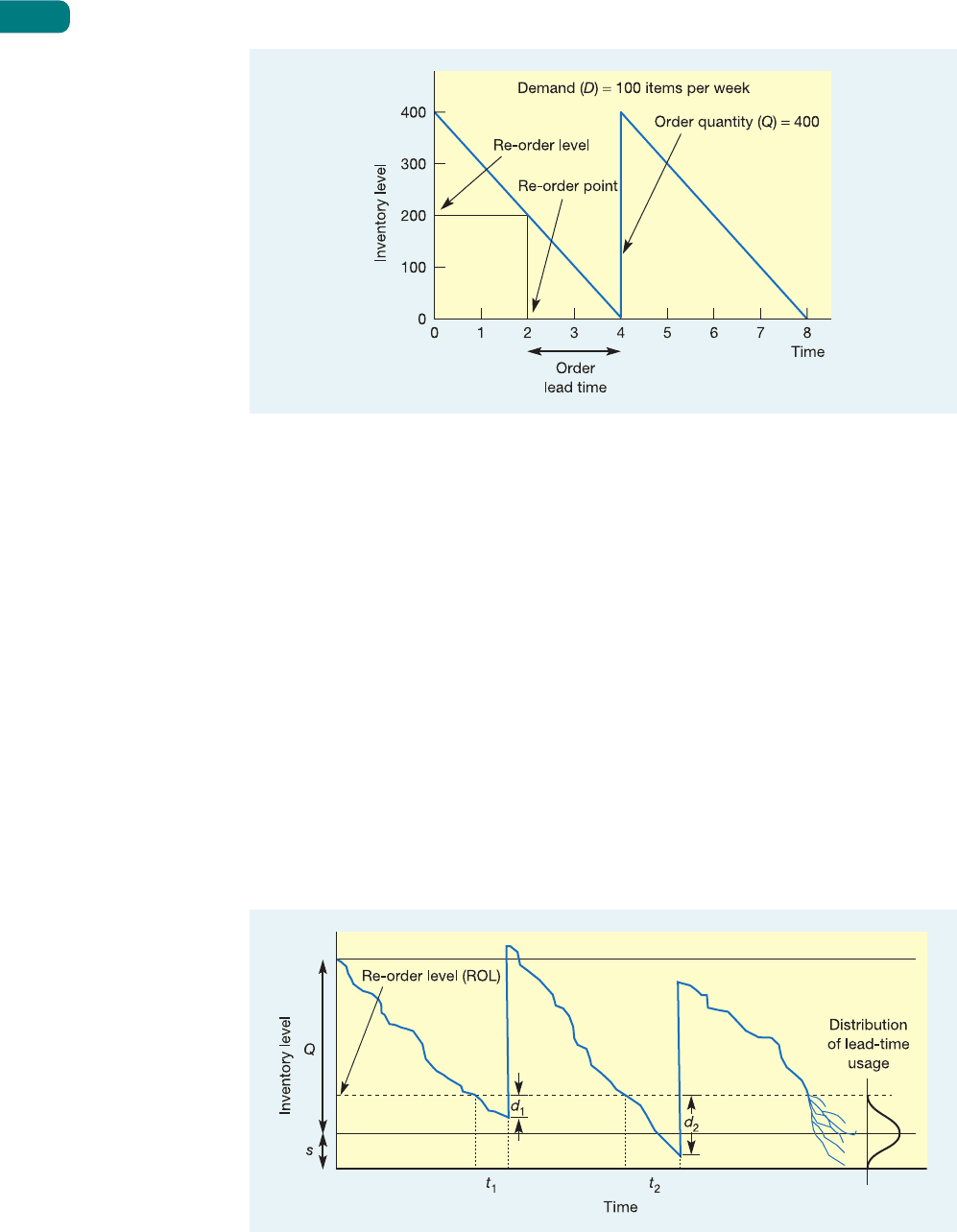

However, this assumes that both the demand and the order lead time are perfectly pre-

dictable. In most cases, of course, this is not so. Both demand and the order lead time are

likely to vary to produce a profile which looks something like that in Figure 12.12. In these

circumstances it is necessary to make the replenishment order somewhat earlier than would

be the case in a purely deterministic situation. This will result in, on average, some stock still

being in the inventory when the replenishment order arrives. This is buffer (safety) stock.

The earlier the replenishment order is placed, the higher will be the expected level of safety

stock (s) when the replenishment order arrives. But because of the variability of both lead

time (t) and demand rate (d), there will sometimes be a higher-than-average level of safety

stock and sometimes lower. The main consideration in setting safety stock is not so much the

average level of stock when a replenishment order arrives but rather the probability that the

stock will not have run out before the replenishment order arrives.

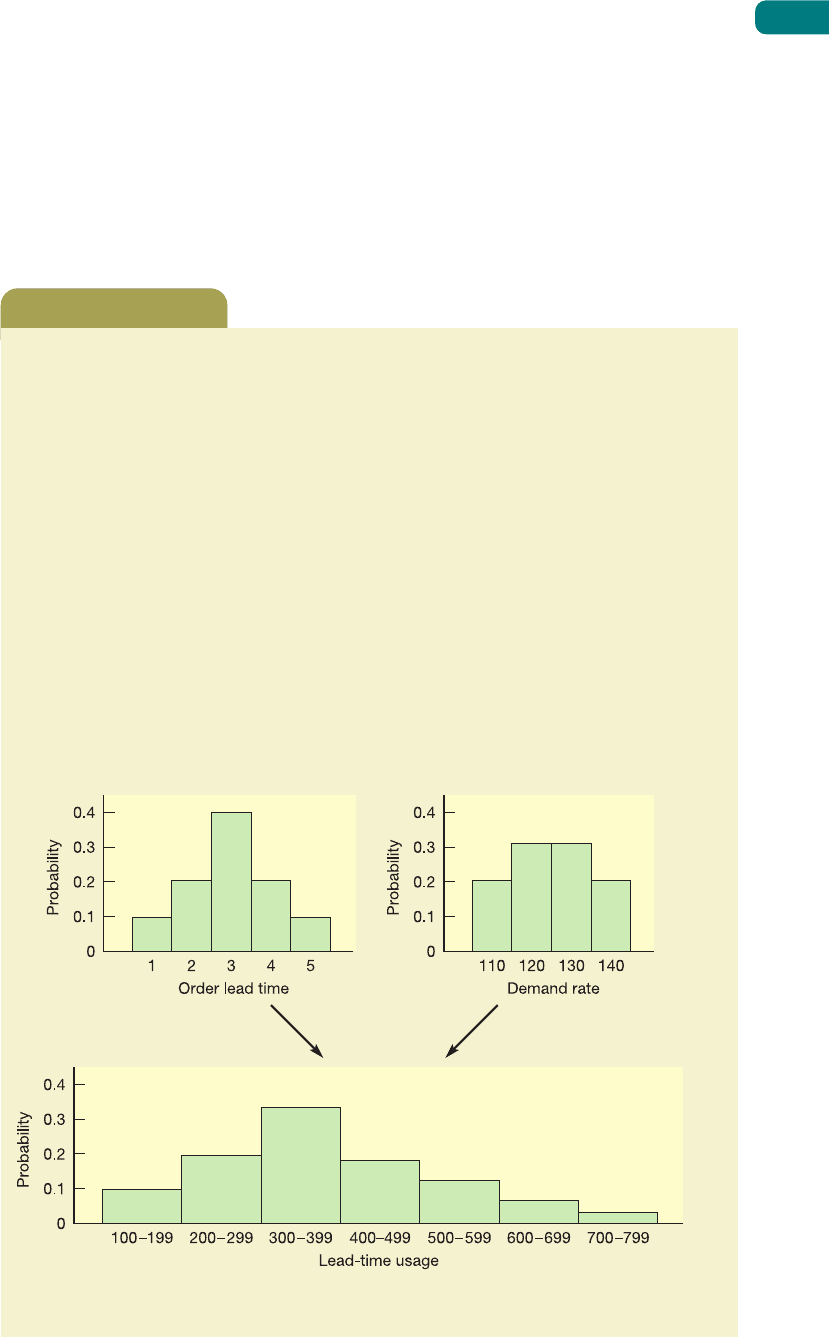

The key statistic in calculating how much safety stock to allow is the probability distribu-

tion which shows the lead-time usage. The lead-time usage distribution is a combination of

Re-order level

Lead-time usage

Part Three Planning and control

358

Figure 12.11 Re-order level (ROL) and re-order point (ROP) are derived from the order lead

time and demand rate

Figure 12.12 Safety stock (s) helps to avoid stock-outs when demand and/or order lead time

are uncertain

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 358

the distributions which describe lead-time variation and the demand rate during the lead time.

If safety stock is set below the lower limit of this distribution then there will be shortages

every single replenishment cycle. If safety stock is set above the upper limit of the distribution,

there is no chance of stock-outs occurring. Usually, safety stock is set to give a predetermined

likelihood that stock-outs will not occur. Figure 12.12 shows that, in this case, the first replenish-

ment order arrived after t

1

, resulting in a lead-time usage of d

1

. The second replenishment

order took longer, t

2

, and demand rate was also higher, resulting in a lead-time usage of d

2

.

The third order cycle shows several possible inventory profiles for different conditions of

lead-time usage and demand rate.

Chapter 12 Inventory planning and control

359

A company which imports running shoes for sale in its sports shops can never be certain

of how long, after placing an order, the delivery will take. Examination of previous orders

reveals that out of ten orders: one took one week, two took two weeks, four took three

weeks, two took four weeks and one took five weeks. The rate of demand for the shoes

also varies between 110 pairs per week and 140 pairs per week. There is a 0.2 probability

of the demand rate being either 110 or 140 pairs per week, and a 0.3 chance of demand

being either 120 or 130 pairs per week. The company needs to decide when it should place

replenishment orders if the probability of a stock-out is to be less than 10 per cent.

Both lead time and the demand rate during the lead time will contribute to the lead-

time usage. So the distributions which describe each will need to be combined. Figure 12.13

and Table 12.2 show how this can be done. Taking lead time to be one, two, three, four

or five weeks, and demand rate to be 110, 120, 130 or 140 pairs per week, and also assum-

ing the two variables to be independent, the distributions can be combined as shown in

Table 12.2. Each element in the matrix shows a possible lead-time usage with the prob-

ability of its occurrence. So if the lead time is one week and the demand rate is 110 pairs

per week, the actual lead-time usage will be 1 × 110 = 110 pairs. Since there is a 0.1 chance

of the lead time being one week, and a 0.2 chance of demand rate being 110 pairs per

week, the probability of both these events occurring is 0.1 × 0.2 = 0.02.

Worked example

Figure 12.13 The probability distributions for order lead time and demand rate combine

to give the lead-time usage distribution

➔

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 359

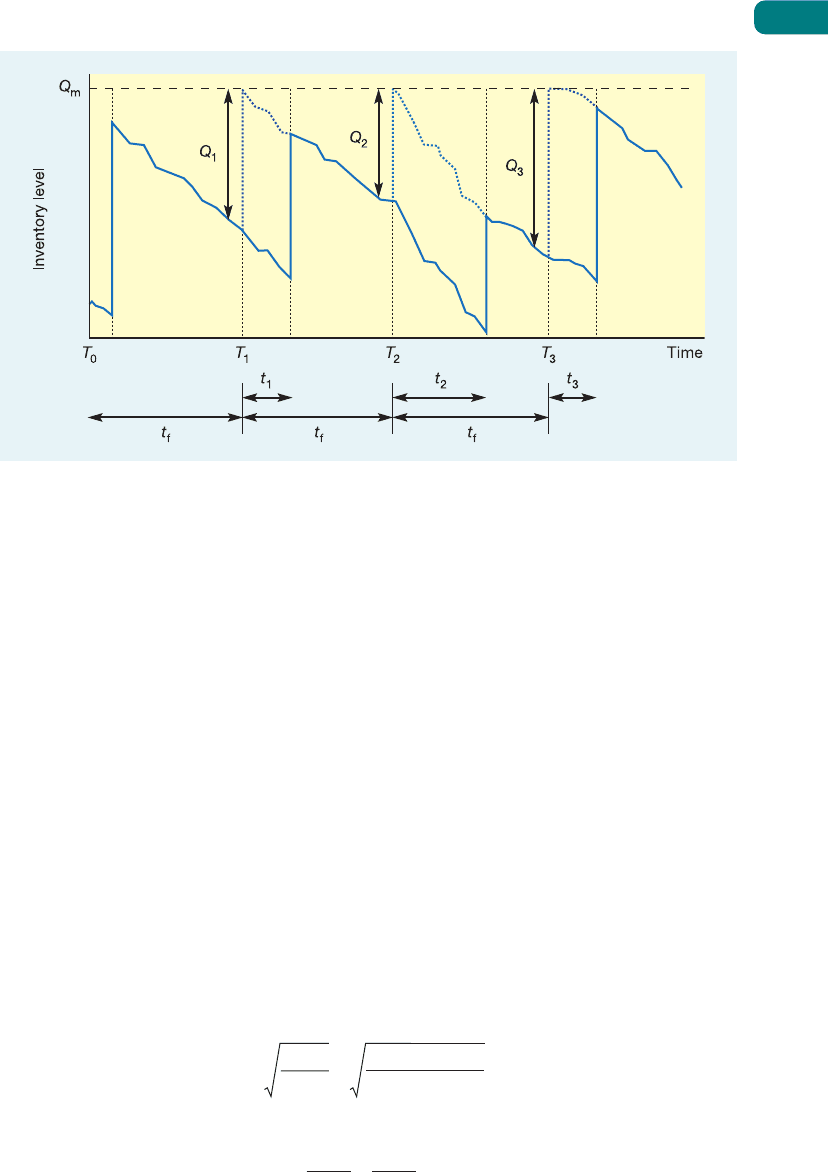

Continuous and periodic review

The approach we have described to making the replenishment timing decision is often called

the continuous review approach. This is because, to make the decision in this way, there

must be a process to review the stock level of each item continuously and then place an order

when the stock level reaches its re-order level. The virtue of this approach is that, although

the timing of orders may be irregular (depending on the variation in demand rate), the order

size (Q) is constant and can be set at the optimum economic order quantity. Such continual

checking on inventory levels can be time-consuming, especially when there are many stock

withdrawals compared with the average level of stock, but in an environment where all

inventory records are computerized, this should not be a problem unless the records are

inaccurate.

An alternative and far simpler approach, but one which sacrifices the use of a fixed (and

therefore possibly optimum) order quantity, is called the periodic review approach. Here,

rather than ordering at a predetermined re-order level, the periodic approach orders at a

Continuous review

Periodic review

Part Three Planning and control

360

We can now classify the possible lead-time usages into histogram form. For example,

summing the probabilities of all the lead-time usages which fall within the range 100–199

(all the first column) gives a combined probability of 0.1. Repeating this for subsequent

intervals results in Table 12.3.

This shows the probability of each possible range of lead-time usage occurring, but

it is the cumulative probabilities that are needed to predict the likelihood of stock-out

(see Table 12.4).

Setting the re-order level at 600 would mean that there is only a 0.08 chance of usage

being greater than available inventory during the lead time, i.e. there is a less than 10 per

cent chance of a stock-out occurring.

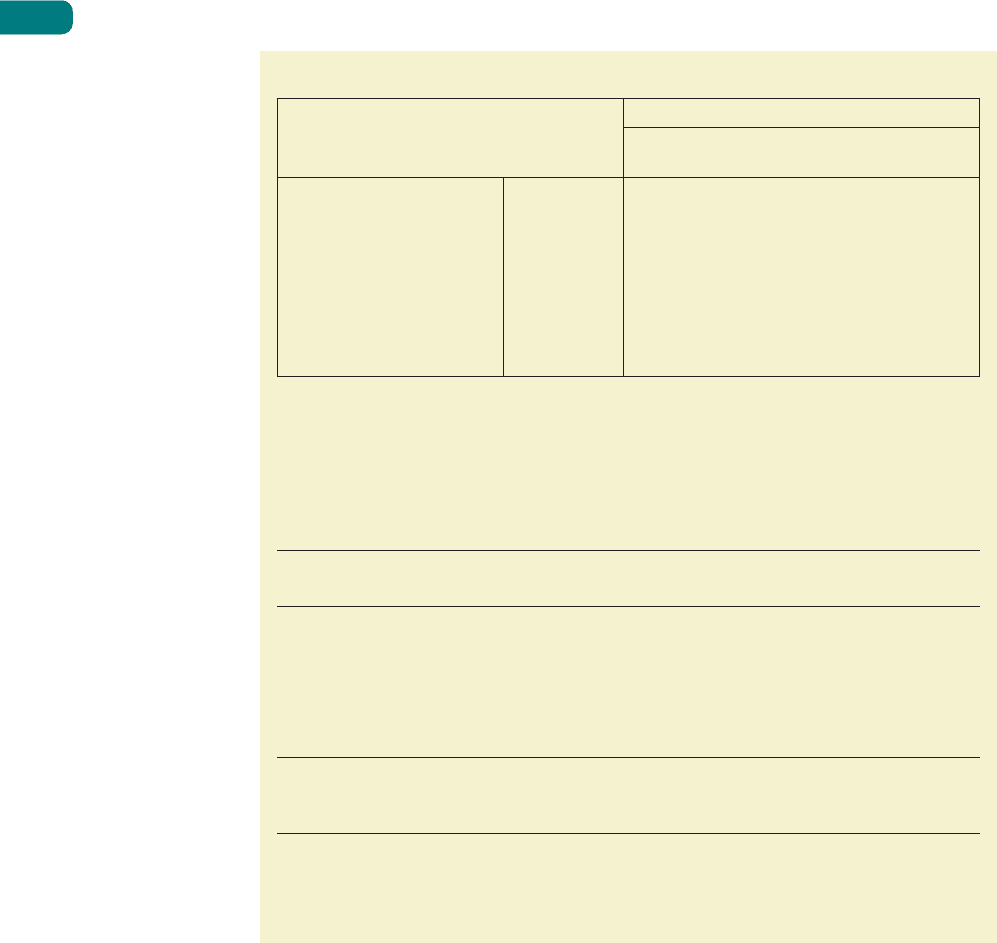

Table 12.2 Matrix of lead-time and demand-rate probabilities

Lead-time probabilities

12345

0.1 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.1

110 0.2 110 220 330 440 550

(0.02) (0.04) (0.08) (0.04) (0.02)

120 0.3 120 240 360 480 600

(0.03) (0.06) (0.12) (0.06) (0.03)

Demand-rate probabilities

130 0.3 130 260 390 520 650

(0.03) (0.06) (0.12) (0.06) (0.03)

140 0.2 140 280 420 560 700

(0.02) (0.04) (0.08) (0.04) (0.02)

Table 12.3 Combined probabilities

Lead-time usage 100–199 200–299 300–399 400–499 500–599 600–699 700–799

Probability 0.1 0.2 0.32 0.18 0.12 0.06 0.02

Table 12.4 Combined probabilities

Lead-time usage X 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800

Probability of usage

being greater than X 1.0 0.9 0.7 0.38 0.2 0.08 0.02 0

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 360

fixed and regular time interval. So the stock level of an item could be found, for example,

at the end of every month and a replenishment order placed to bring the stock up to a pre-

determined level. This level is calculated to cover demand between the replenishment order

being placed and the following replenishment order arriving. Figure 12.14 illustrates the

parameters for the periodic review approach.

At time T

1

in Figure 12.14 the inventory manager would examine the stock level and

order sufficient to bring it up to some maximum, Q

m

. However, that order of Q

1

items will

not arrive until a further time of t

1

has passed, during which demand continues to deplete

the stocks. Again, both demand and lead time are uncertain. The Q

1

items will arrive and

bring the stock up to some level lower than Q

m

(unless there has been no demand during t

1

).

Demand then continues until T

2

, when again an order Q

2

is placed which is the difference

between the current stock at T

2

and Q

m

. This order arrives after t

2

, by which time demand

has depleted the stocks further. Thus the replenishment order placed at T

1

must be able to

cover for the demand which occurs until T

2

and t

2

. Safety stocks will need to be calculated,

in a similar manner to before, based on the distribution of usage over this period.

The time interval

The interval between placing orders, t

1

, is usually calculated on a deterministic basis, and

derived from the EOQ. So, for example, if the demand for an item is 2,000 per year, the cost

of placing an order £25, and the cost of holding stock £0.5 per item per year:

EOQ == =447

The optimum time interval between orders, t

f

, is therefore:

t

f

==years

= 2.68 months

It may seem paradoxical to calculate the time interval assuming constant demand when

demand is, in fact, uncertain. However, uncertainties in both demand and lead time can be

allowed for by setting Q

m

to allow for the desired probability of stock-out based on usage

during the period t

f

+ lead time.

447

2,000

EOQ

D

2 × 2,000 × 25

0.5

2C

o

D

C

h

Chapter 12 Inventory planning and control

361

Figure 12.14 A periodic review approach to order timing with probabilistic demand and

lead time

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 361

Part Three Planning and control

362

Figure 12.15 The two-bin and three-bin systems of re-ordering

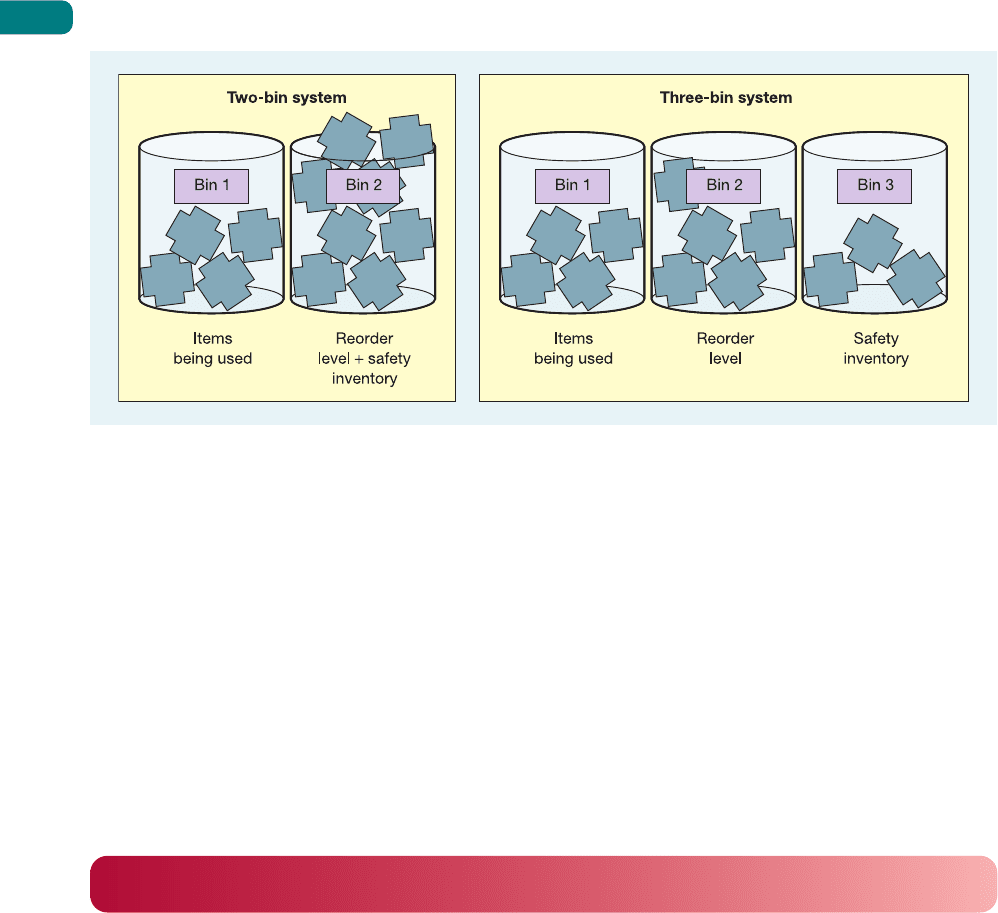

Two-bin and three-bin systems

Keeping track of inventory levels is especially important in continuous review approaches

to re-ordering. A simple and obvious method of indicating when the re-order point has

been reached is necessary, especially if there are a large number of items to be monitored. The

two- and three-bin systems illustrated in Figure 12.15 are such methods. The simple two-bin

system involves storing the re-order point quantity plus the safety inventory quantity in the

second bin and using parts from the first bin. When the first bin empties, that is the signal to

order the next re-order quantity. Sometimes the safety inventory is stored in a third bin (the

three-bin system), so it is clear when demand is exceeding that which was expected. Different

‘bins’ are not always necessary to operate this type of system. For example, a common practice

in retail operations is to store the second ‘bin’ quantity upside-down behind or under the

first ‘bin’ quantity. Orders are then placed when the upside-down items are reached.

Inventory analysis and control systems

The models we have described, even the ones which take a probabilistic view of demand

and lead time, are still simplified compared with the complexity of real stock management.

Coping with many thousands of stocked items, supplied by many hundreds of different

suppliers, with possibly tens of thousands of individual customers, makes for a complex and

dynamic operations task. In order to control such complexity, operations managers have to

do two things. First, they have to discriminate between different stocked items, so that they

can apply a degree of control to each item which is appropriate to its importance. Second,

they need to invest in an information-processing system which can cope with their particu-

lar set of inventory control circumstances.

Inventory priorities – the ABC system

In any inventory which contains more than one stocked item, some items will be more

important to the organization than others. Some, for example, might have a very high usage

rate, so if they ran out many customers would be disappointed. Other items might be of

particularly high value, so excessively high inventory levels would be particularly expensive.

One common way of discriminating between different stock items is to rank them by the

Two-bin system

Three-bin system

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 362

usage value (their usage rate multiplied by their individual value). Items with a particularly

high usage value are deemed to warrant the most careful control, whereas those with low

usage values need not be controlled quite so rigorously. Generally, a relatively small propor-

tion of the total range of items contained in an inventory will account for a large proportion

of the total usage value. This phenomenon is known as the Pareto law (after the person who

described it), sometimes referred to as the 80/20 rule. It is called this because, typically,

80 per cent of an operation’s sales are accounted for by only 20 per cent of all stocked item

types. The relationship can be used to classify the different types of items kept in an inventory

by their usage value. ABC inventory control allows inventory managers to concentrate their

efforts on controlling the more significant items of stock.

● Class A items are those 20 per cent or so of high-usage-value items which account for

around 80 per cent of the total usage value.

● Class B items are those of medium usage value, usually the next 30 per cent of items which

often account for around 10 per cent of the total usage value.

● Class C items are those low-usage-value items which, although comprising around 50 per

cent of the total types of items stocked, probably only account for around 10 per cent of

the total usage value of the operation.

Usage value

Pareto law

ABC inventory control

Chapter 12 Inventory planning and control

363

Table 12.5 shows all the parts stored by an electrical wholesaler. The 20 different items

stored vary in terms of both their usage per year and cost per item as shown. However,

the wholesaler has ranked the stock items by their usage value per year. The total usage

value per year is £5,569,000. From this it is possible to calculate the usage value per year

of each item as a percentage of the total usage value, and from that a running cumulative

total of the usage value as shown. The wholesaler can then plot the cumulative percentage

of all stocked items against the cumulative percentage of their value. So, for example, the

part with stock number A/703 is the highest-value part and accounts for 25.14 per cent

Worked example

Table 12.5 Warehouse items ranked by usage value

Stock no. Usage Cost Usage value % of total Cumulative

(items/year) (£/item) (£000/year) value % of total value

A/703 700 20.00 1,400 25.14 25.14

D/012 450 2.75 1,238 22.23 47.37

A/135 1,000 0.90 900 16.16 63.53

C/732 95 8.50 808 14.51 78.04

C/375 520 0.54 281 5.05 83.09

A/500 73 2.30 168 3.02 86.11

D/111 520 0.22 114 2.05 88.16

D/231 170 0.65 111 1.99 90.15

E/781 250 0.34 85 1.53 91.68

A/138 250 0.30 75 1.34 93.02

D/175 400 0.14 56 1.01 94.03

E/001 80 0.63 50 0.89 94.92

C/150 230 0.21 48 0.86 95.78

F/030 400 0.12 48 0.86 96.64

D/703 500 0.09 45 0.81 97.45

D/535 50 0.88 44 0.79 98.24

C/541 70 0.57 40 0.71 98.95

A/260 50 0.64 32 0.57 99.52

B/141 50 0.32 16 0.28 99.80

D/021 20 0.50 10 0.20 100.00

Total 5,569 100.00

➔

M12_SLAC0460_06_SE_C12.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 363