Nigel S., Chambers S., Johnson R. Operations Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Part Two Design

154

and

H =

where

x

i

= the x coordinate of source or destination i

y

i

= the y coordinate of source or destination i

V

i

= the amount to be shipped to or from source or destination i.

Each of the garden centres is of a different size and has different sales volumes. In

terms of the number of truck loads of products sold each week, Table 6.3 shows the sales

of the four centres.

∑y

i

V

i

∑V

i

In this case

G ==5.34

and

H ==2.4

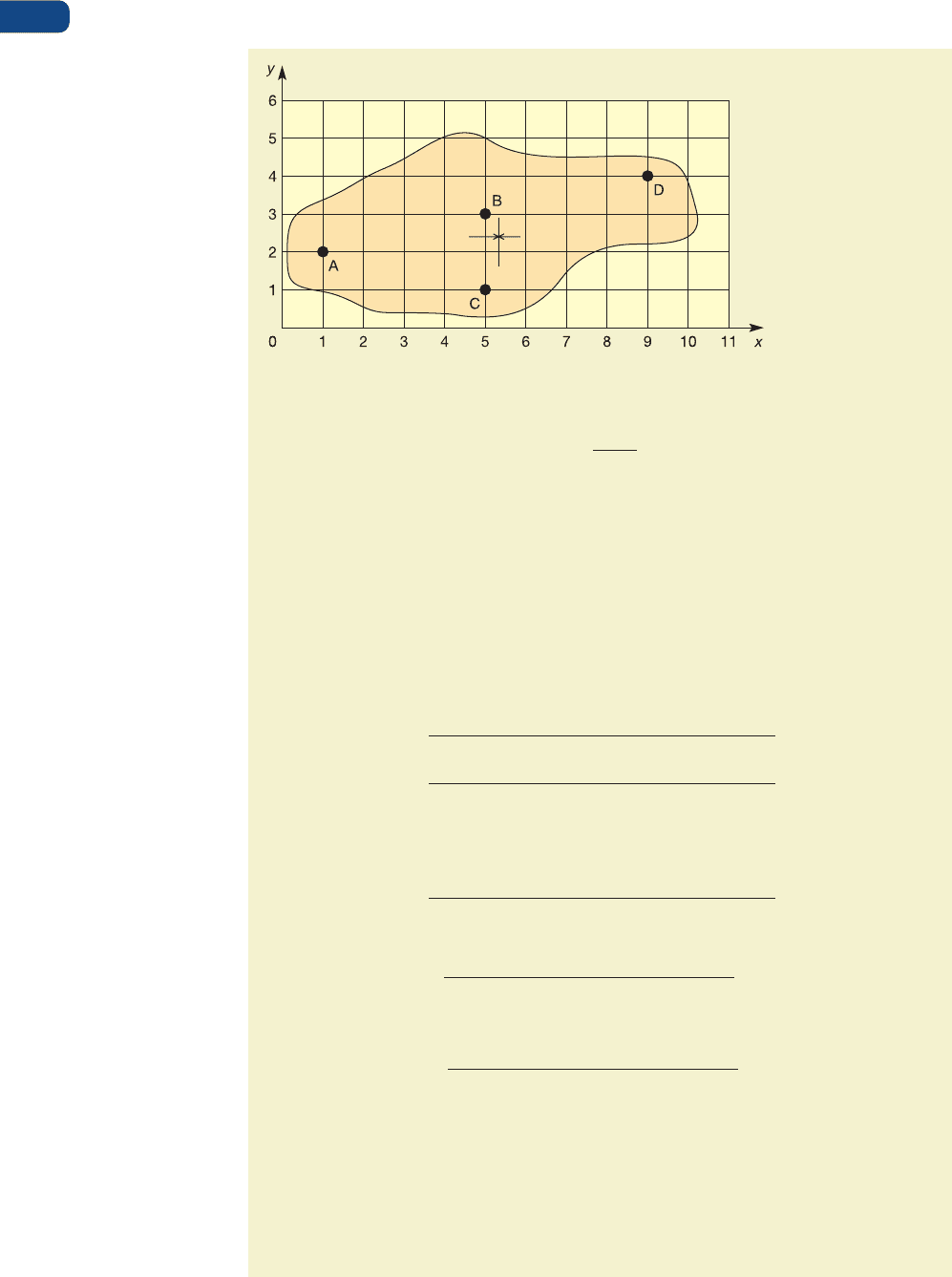

So the minimum cost location for the warehouse is at point (5.34, 2.4) as shown in

Figure 6.7. That is, at least, theoretically. In practice, the optimum location might also be

influenced by other factors such as the transportation network. So if the optimum loca-

tion was at a point with poor access to a suitable road or at some other unsuitable location

(in a residential area or the middle of a lake, for example) then the chosen location will need

to be adjusted. The technique does go some way, however, towards providing an indication

of the area in which the company should be looking for sites for its warehouse.

(2 × 5) + (3 × 10) + (1 × 12) + (4 × 8)

35

(1 × 5) + (5 × 10) + (5 × 12) + (9 × 8)

35

Table 6.3 The weekly demand levels (in truck

loads) at each of the four garden centres

Sales per week

(truck loads)

Garden centre A 5

Garden centre B 10

Garden centre C 12

Garden centre D 8

Total 35

Figure 6.7 Centre-of-gravity location for the garden centre warehouse

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 154

Chapter 6 Supply network design

155

Long-term capacity management

The next set of supply network decisions concern the size or capacity of each part of the

network. Here we shall treat capacity in a general long-term sense. The specific issues

involved in measuring and adjusting capacity in the medium and short terms are examined

in Chapter 11.

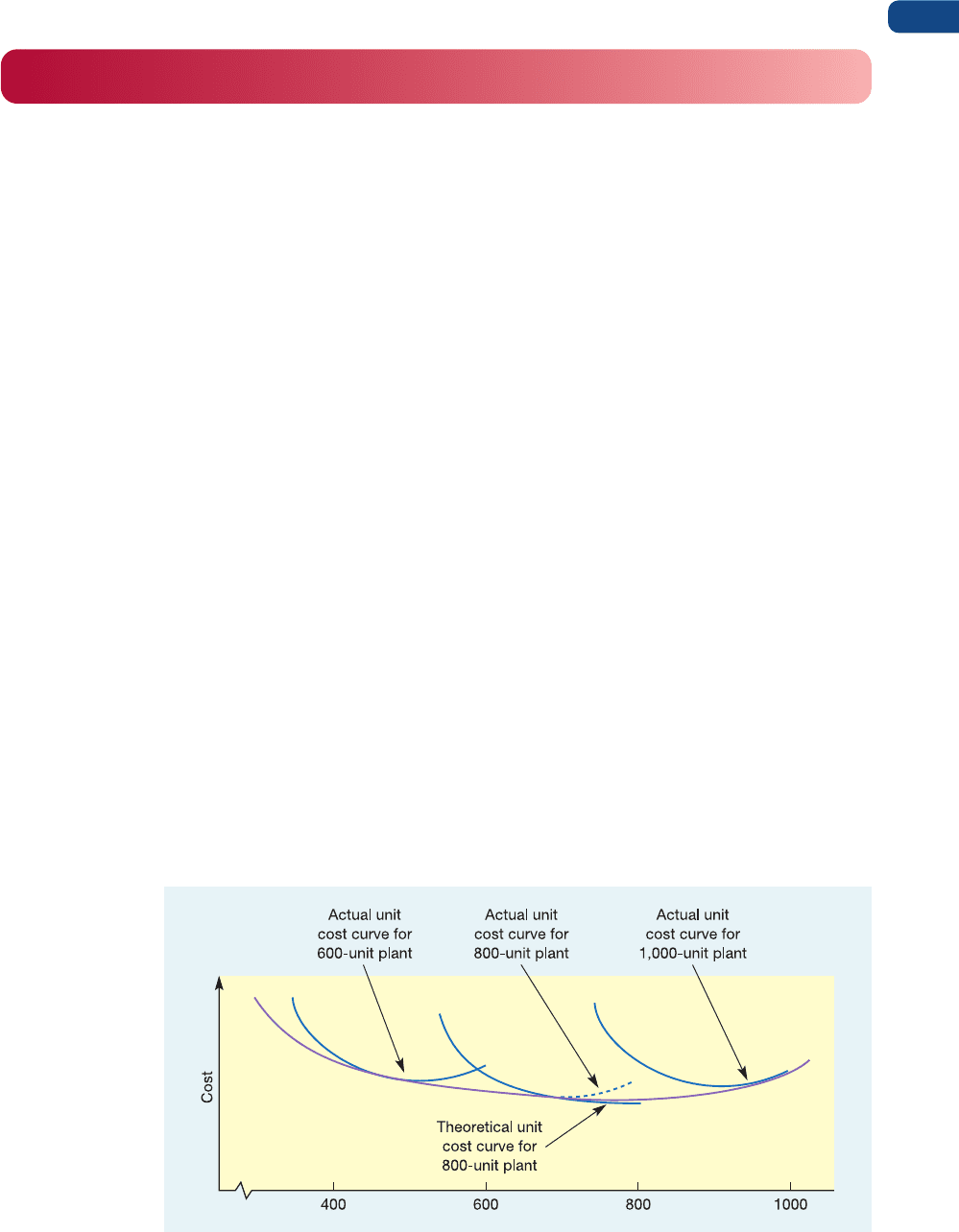

The optimum capacity level

Most organizations need to decide on the size (in terms of capacity) of each of their facilities.

An air-conditioning unit company, for example, might operate plants each of which has

a capacity (at normal product mix) of 800 units per week. At activity levels below this, the

average cost of producing each unit will increase because the fixed costs of the factory are

being covered by fewer units produced. The total production costs of the factory have some

elements which are fixed – they will be incurred irrespective of how much, or little, the

factory produces. Other costs are variable – they are the costs incurred by the factory for each

unit it produces. Between them, the fixed and variable costs make up the total cost at any

output level. Dividing this cost by the output level itself will give the theoretical average cost

of producing units at that output rate. This is the green line shown as the theoretical unit

cost curve for the 800-unit plant in Figure 6.8. However, the actual average cost curve may

be different from this line for a number of reasons:

● All fixed costs are not incurred at one time as the factory starts to operate. Rather they occur

at many points (called fixed-cost breaks) as volume increases. This makes the theoretically

smooth average cost curve more discontinuous.

● Production levels may be increased above the theoretical capacity of the plant, by using

prolonged overtime, for example, or temporarily subcontracting some parts of the work.

● There may be less obvious cost penalties of operating the plant at levels close to or above

its nominal capacity. For example, long periods of overtime may reduce productivity

levels as well as costing more in extra payments to staff; operating plant for long periods

with reduced maintenance time may increase the chances of breakdown, and so on. This

usually means that average costs start to increase after a point which will often be lower

than the theoretical capacity of the plant.

Fixed-cost breaks

Figure 6.8 Unit cost curves for individual plants of varying capacities and the unit cost curve

for this type of plant as its capacity varies

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 155

The blue dotted line in Figure 6.8 shows this effect. The two other blue lines show similar

curves for a 600-unit plant and a 1,000-unit plant. Figure 6.8 also shows that a similar rela-

tionship occurs between the average-cost curves for plants of increasing size. As the nominal

capacity of the plants increases, the lowest-cost points at first reduce. There are two main rea-

sons for this:

● The fixed costs of an operation do not increase proportionately as its capacity increases.

An 800-unit plant has less than twice the fixed costs of a 400-unit plant.

● The capital costs of building the plant do not increase proportionately to its capacity. An

800-unit plant costs less to build than twice the cost of a 400-unit plant.

These two factors, taken together, are often referred to as economies of scale. However,

above a certain size, the lowest-cost point may increase. In Figure 6.8 this happens with plants

above 800 units capacity. This occurs because of what are called the diseconomies of scale,

two of which are particularly important. First, transportation costs can be high for large

operations. For example, if a manufacturer supplies its global market from one major plant

in Denmark, materials may have to be brought in to, and shipped from, several countries.

Second, complexity costs increase as size increases. The communications and coordination

effort necessary to manage an operation tends to increase faster than capacity. Although not

seen as a direct cost, it can nevertheless be very significant.

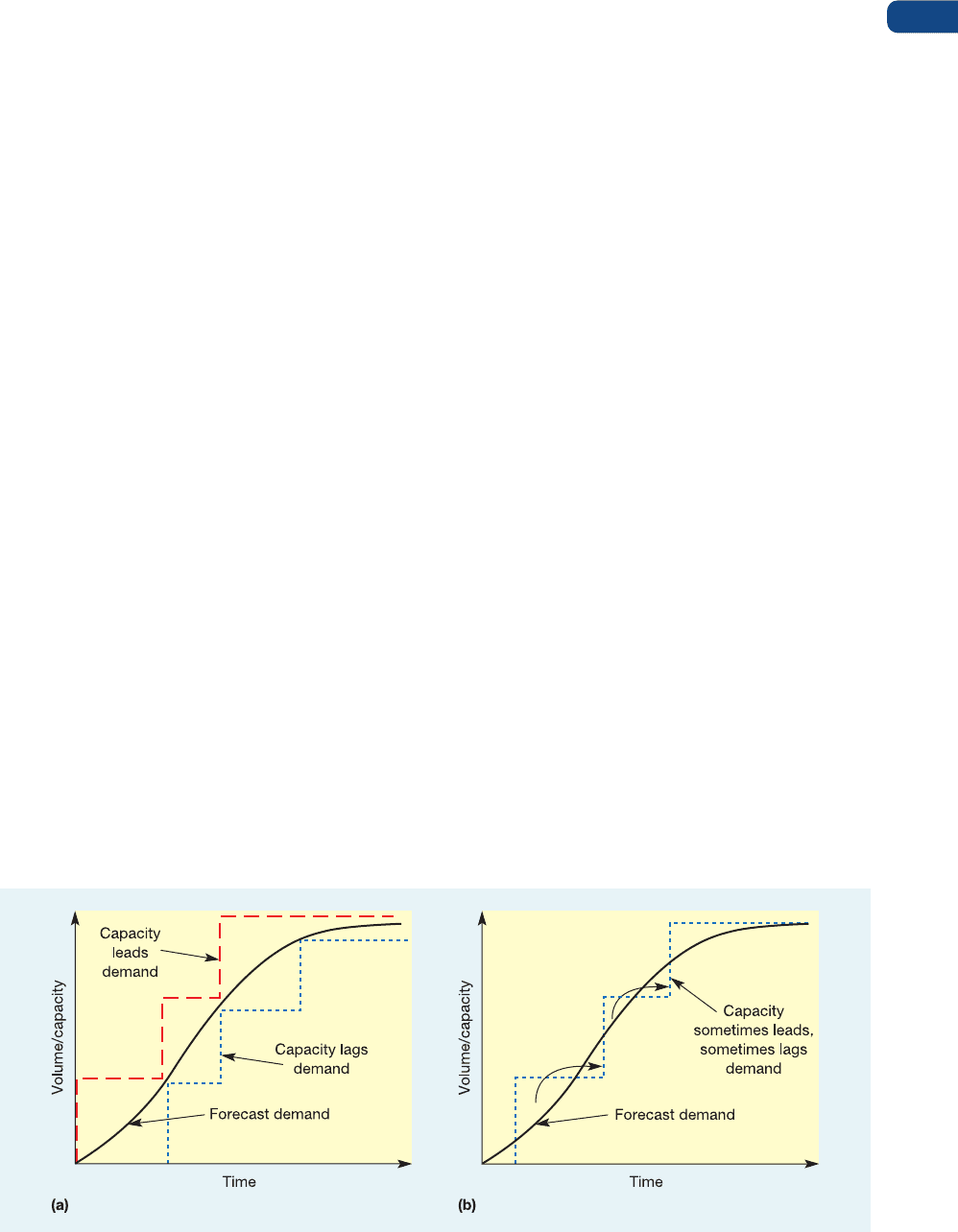

Scale of capacity and the demand–capacity balance

Large units of capacity also have some disadvantages when the capacity of the operation is

being changed to match changing demand. For example, suppose that the air-conditioning unit

manufacturer forecasts demand increase over the next three years, as shown in Figure 6.9,

to level off at around 2,400 units a week. If the company seeks to satisfy all demand by build-

ing three plants, each of 800 units capacity, the company will have substantial amounts of

over-capacity for much of the period when demand is increasing. Over-capacity means low

capacity utilization, which in turn means higher unit costs. If the company builds smaller

plants, say 400-unit plants, there will still be over-capacity but to a lesser extent, which means

higher capacity utilization and possibly lower costs.

Part Two Design

156

Figure 6.9 The scale of capacity increments affects the utilization of capacity

Economies of scale

Diseconomies of scale

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 156

Balancing capacity

As we discussed in Chapter 1, all operations are made up of separate processes, each of

which will itself have its own capacity. So, for example, the 800-unit air-conditioning plant

may not only assemble the products but may also manufacture the parts from which they are

made, pack, store and load them in a warehouse and distribute them to customers. If demand

is 800 units per week, not only must the assembly process have a capacity sufficient for this

output, but the parts manufacturing processes, warehouse and distribution fleet of trucks

must also have sufficient capacity. For the network to operate efficiently, all its stages must

have the same capacity. If not, the capacity of the network as a whole will be limited to the

capacity of its slowest link.

The timing of capacity change

Changing the capacity of an operation is not just a matter of deciding on the best size of

a capacity increment. The operation also needs to decide when to bring ‘on-stream’ new

capacity. For example, Figure 6.10 shows the forecast demand for the new air-conditioning

unit. The company has decided to build 400-unit-per-week plants in order to meet the

growth in demand for its new product. In deciding when the new plants are to be introduced

the company must choose a position somewhere between two extreme strategies:

● capacity leads demand – timing the introduction of capacity in such a way that there is

always sufficient capacity to meet forecast demand;

● capacity lags demand – timing the introduction of capacity so that demand is always equal

to or greater than capacity.

Figure 6.10(a) shows these two extreme strategies, although in practice the company is

likely to choose a position somewhere between the two. Each strategy has its own advantages

and disadvantages. These are shown in Table 6.4. The actual approach taken by any com-

pany will depend on how it views these advantages and disadvantages. For example, if the

company’s access to funds for capital expenditure is limited, it is likely to find the delayed

capital expenditure requirement of the capacity-lagging strategy relatively attractive.

Chapter 6 Supply network design

157

Figure 6.10 (a) Capacity-leading and capacity-lagging strategies, (b) Smoothing with inventories means using the

excess capacity in one period to produce inventory that supplies the under-capacity period

Capacity leading

Capacity lagging

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 157

‘Smoothing’ with inventory

The strategy on the continuum between pure leading and pure lagging strategies can be

implemented so that no inventories are accumulated. All demand in one period is satisfied

(or not) by the activity of the operation in the same period. Indeed, for customer-processing

operations there is no alternative to this. A hotel cannot satisfy demand in one year by

using rooms which were vacant the previous year. For some materials- and information-

processing operations, however, the output from the operation which is not required in

one period can be stored for use in the next period. The economies of using inventories are

fully explored in Chapter 12. Here we confine ourselves to noting that inventories can be

used to obtain the advantages of both capacity leading and capacity lagging. Figure 6.10(b)

shows how this can be done. Capacity is introduced such that demand can always be

met by a combination of production and inventories, and capacity is, with the occasional

exception, fully utilized. This may seem like an ideal state. Demand is always met and so

revenue is maximized. Capacity is usually fully utilized and so costs are minimized. There is

a price to pay, however, and that is the cost of carrying the inventories. Not only will these

have to be funded but the risks of obsolescence and deterioration of stock are introduced.

Table 6.5 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of the ‘smoothing-with-inventory’

strategy.

Part Two Design

158

Table 6.4 The arguments for and against pure leading and pure lagging strategies of

capacity timing

Advantages

Capacity-leading strategies

Always sufficient capacity to meet demand,

therefore revenue is maximized and

customers satisfied

Most of the time there is a ‘capacity cushion’

which can absorb extra demand if forecasts

are pessimistic

Any critical start-up problems with new plants

are less likely to affect supply to customers

Capacity-lagging strategies

Always sufficient demand to keep the plants

working at full capacity, therefore unit costs

are minimized

Over-capacity problems are minimized if

forecasts are optimistic

Capital spending on the plants is delayed

Disadvantages

Utilization of the plants is always relatively low,

therefore costs will be high

Risks of even greater (or even permanent)

over-capacity if demand does not reach

forecast levels

Capital spending on plant early

Insufficient capacity to meet demand fully,

therefore reduced revenue and dissatisfied

customers

No ability to exploit short-term increases in

demand

Under-supply position even worse if there are

start-up problems with the new plants

Table 6.5 The advantages and disadvantages of a smoothing-with-inventory strategy

Advantages

All demand is satisfied, therefore customers are

satisfied and revenue is maximized

Utilization of capacity is high and therefore

costs are low

Very short-term surges in demand can be met

from inventories

Disadvantages

The cost of inventories in terms of working

capital requirements can be high. This is

especially serious at a time when the company

requires funds for its capital expansion

Risks of product deterioration and

obsolescence

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 158

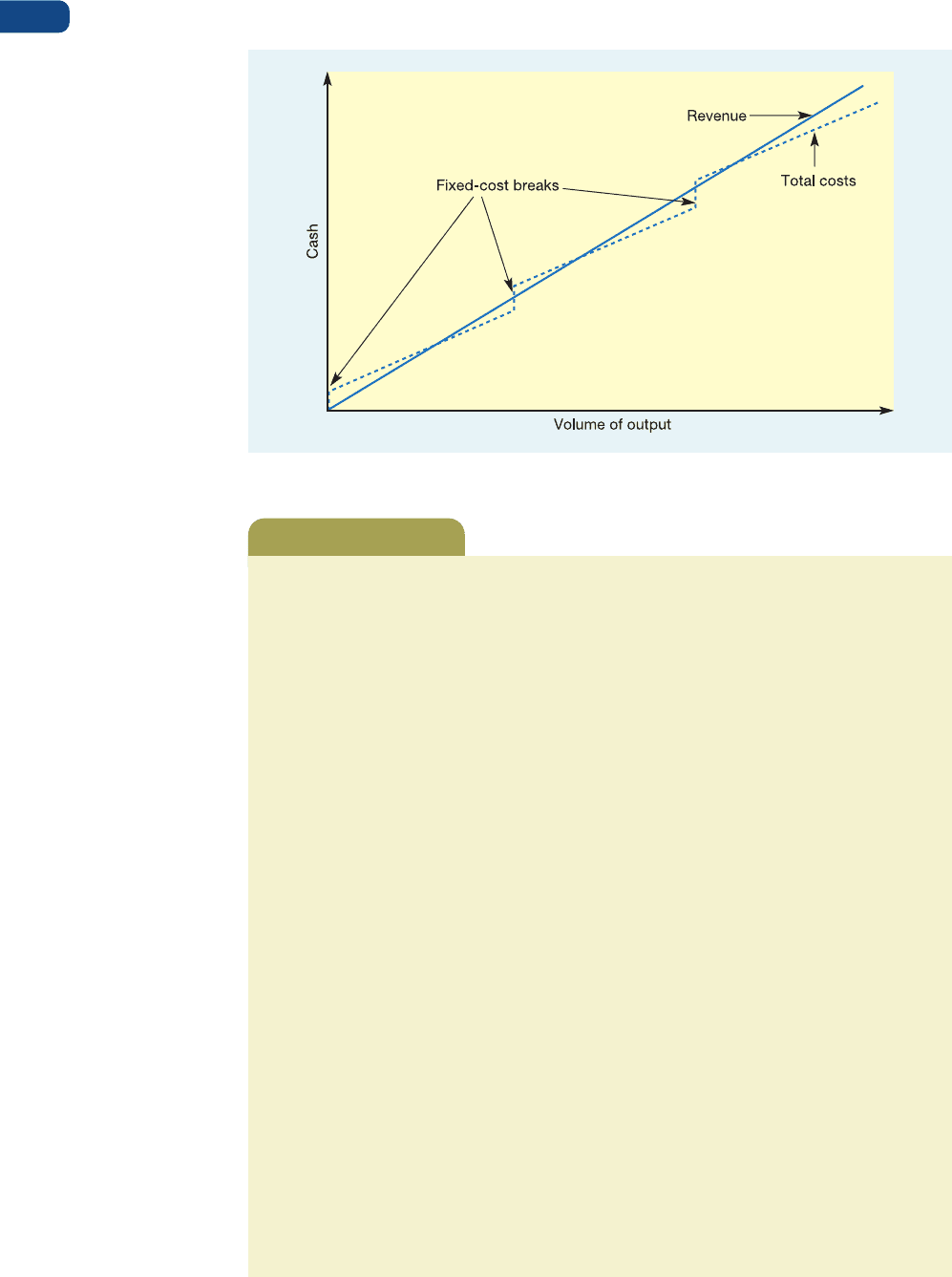

Break-even analysis of capacity expansion

An alternative view of capacity expansion can be gained by examining the cost implications

of adding increments of capacity on a break-even basis. Figure 6.11 shows how increasing

capacity can move an operation from profitability to loss. Each additional unit of capacity results

in a fixed-cost break that is a further lump of expenditure which will have to be incurred

before any further activity can be undertaken in the operation. The operation is unlikely

to be profitable at very low levels of output. Eventually, assuming that prices are greater

than marginal costs, revenue will exceed total costs. However, the level of profitability at the

point where the output level is equal to the capacity of the operation may not be sufficient

to absorb all the extra fixed costs of a further increment in capacity. This could make the

operation unprofitable in some stages of its expansion.

Chapter 6 Supply network design

159

A business process outsourcing (BPO) company is considering building some process-

ing centres in India. The company has a standard call centre design that it has found

to be the most efficient around the world. Demand forecasts indicate that there is

already demand from potential clients to fully utilize one process centre that would

generate $10 million of business per quarter (3-month period). The forecasts also

indicate that by quarter 6 there will be sufficient demand to fully utilize one further pro-

cessing centre. The costs of running a single centre are estimated to be $5 million per

quarter and the lead time between ordering a centre and it being fully operational is

two quarters. The capital costs of building a centre is $10 million, $5 million of which

is payable before the end of the first quarter after ordering, and $5 million payable

before the end of the second quarter after ordering. How much funding will the com-

pany have to secure on a quarter-by-quarter basis if it decides to build one processing

centre as soon as possible and a second processing centre to be operational by the

beginning of quarter 6?

Analysis

The funding required for a capacity expansion such as this can be derived by calculat-

ing the amount of cash coming in to the operation each time period, then subtracting

the operating and capital costs for the project each time period. The cumulative cash

flow indicates the funding required for the project. In Table 6.6 these calculations are

performed for eight quarters. For the first two quarters there is a net cash outflow

because capital costs are incurred by no revenue is being earned. After that, revenue is

being earned but in quarters four and five this is partly offset by further capital costs for

the second processing centre. However, from quarter six onwards the additional revenue

from the second processing centre brings the cash flow positive again. The maximum

funding required occurs in quarter two and is $10 million.

Table 6.6 The cumulative cash flow indicating the funding required for the project

Quarters

1 2 345 6 7 7

Sales revenue ($ millions) 0 0 10 10 10 20 20 20

Operating costs ($ millions) 0 0 −5 −5 −5 −10 −10 −10

Capital costs ($ millions) −5 −5 −0 −5 −5000

Required cumulative funding ($ millions) −5 −10 −5 −5 −5 +5 +15 +25

Worked example

Fixed-cost breaks are

important in determining

break-even points

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 159

Part Two Design

160

Figure 6.11 Repeated incurring of fixed costs can raise total costs above revenue

A specialist graphics company is investing in a new machine which enables it to make

high-quality prints for its clients. Demand for these prints is forecast to be around

100,000 units in year 1 and 220,000 units in year 2. The maximum capacity of each

machine the company will buy to process these prints is 100,000 units per year. They

have a fixed cost of a200,000 per year and a variable cost of processing of a1 per unit.

The company believe they will be able to charge a4 per unit for producing the prints.

Question

What profit are they likely to make in the first and second years?

Year 1 demand = 100,000 units; therefore company will need one machine

Cost of manufacturing = fixed cost for one machine + variable cost × 100,000

= a200,000 + (a1 × 100,000)

= a300,000

Revenue = demand × price

= 100,000 × a4

= a400,000

Therefore profit = a400,000 − a300,000

= a100,000

Year 2 demand = 220,000; therefore company will need three machines

Cost of manufacturing = fixed cost for three machines + variable cost × 220,000

= (3 × a200,000) + (a1 × 220,000)

= a820,000

Revenue = demand × price

= 220,000 × a4

= a880,000

Therefore profit = a880,000 – a820,000

= a60,000

Note: the profit in the second year will be lower because of the extra fixed costs associ-

ated with the investment in the two extra machines.

Worked example

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 160

Chapter 6 Supply network design

161

Summary answers to key questions

Check and improve your understanding of this chapter using self assessment questions

and a personalised study plan, audio and video downloads, and an eBook – all at

www.myomlab.com.

➤ Why should an organization take a total supply network perspective?

■ The main advantage is that it helps any operation to understand how it can compete effectively

within the network. This is because a supply network approach requires operations managers

to think about their suppliers and their customers as operations. It can also help to identify

particularly significant links within the network and hence identify long-term strategic changes

which will affect the operation.

➤ What is involved in configuring a supply network?

■ There are two main issues involved in configuring the supply network. The first concerns the

overall shape of the supply network. The second concerns the nature and extent of outsourcing

or vertical integration.

■ Changing the shape of the supply network may involve reducing the number of suppliers to the

operation so as to develop closer relationships, any bypassing or disintermediating operations

in the network.

■ Outsourcing or vertical integration concerns the nature of the ownership of the operations within

a supply network. The direction of vertical integration refers to whether an organization wants

to own operations on its supply side or demand side (backwards or forwards integration). The

extent of vertical integration relates to whether an organization wants to own a wide span of

the stage in the supply network. The balance of vertical integration refers to whether operations

can trade with only their vertically integrated partners or with any other organizations.

➤ Where should an operation be located?

■ The stimuli which act on an organization during the location decision can be divided into

supply-side and demand-side influences. Supply-side influences are the factors such as labour,

land and utility costs which change as location changes. Demand-side influences include such

things as the image of the location, its convenience for customers and the suitability of the site

itself.

➤ How much capacity should an operation plan to have?

■ The amount of capacity an organization will have depends on its view of current and future

demand. It is when its view of future demand is different from current demand that this issue

becomes important.

■ When an organization has to cope with changing demand, a number of capacity decisions need

to be taken. These include choosing the optimum capacity for each site, balancing the various

capacity levels of the operation in the network, and timing the changes in the capacity of each

part of the network.

■ Important influences on these decisions include the concepts of economy and diseconomy

of scale, supply flexibility if demand is different from that forecast, and the profitability and

cash-flow implications of capacity timing changes.

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 161

Part Two Design

162

In August 2006, the company behind Disneyland Resort

Paris reported a 13 per cent rise in revenues, saying that

it was making encouraging progress with new rides aimed

at getting more visitors. ‘I am pleased with year-to-date

revenues and especially with third quarter’s, as well as with

the success of the opening of Buzz Lightyear Laser Blast,

the first step of our multi-year investment program. These

results reflect the group’s strategy of increasing growth

through innovative marketing and sales efforts as well as a

multi-year investment program. This performance is encour-

aging as we enter into the important summer months’, said

Chairman and Chief Executive Karl L. Holz. Yet it hadn’t

always been like that. The 14-year history of Disneyland Paris

had more ups and downs than any of its rollercoasters. From

12 April 1992 when EuroDisney opened, through to this more

optimistic report, the resort had been subject simultane-

ously to both wildly optimistic forecasts and widespread

criticism and ridicule. An essay on one critical Internet site

(called ‘An Ugly American in Paris’) summarized the whole

venture in this way. ‘When Disney decided to expand its

hugely successful theme park operations to Europe, it

brought American management styles, American cultural

tastes, American labor practices, and American marketing

pizzazz to Europe. Then, when the French stayed away in

droves, it accused them of cultural snobbery.’

The ‘magic’ of Disney

Since its founding in 1923, The Walt Disney Company had

striven to remain faithful in its commitment to ‘Producing

unparalleled entertainment experiences based on its rich

legacy of quality creative content and exceptional story-

telling’. In the Parks and Resorts division, according to the

company’s description, customers could experience the

‘Magic of Disney’s beloved characters’. It was founded

in 1952, when Walt Disney formed what is now known as

‘Walt Disney Imagineering’ to build Disneyland in Anaheim,

California. By 2006, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts oper-

ated or licensed 11 theme parks at five Disney destinations

around the world. They were: Disneyland Resort, California,

Walt Disney World Resort, Florida, Tokyo Disney Resort,

Disneyland Resort Paris, and their latest park, Hong Kong

Disneyland. In addition, the division operated 35 resort

hotels, two luxury cruise ships and a wide variety of other

entertainment offerings. But perhaps none of its ventures

had proved to be as challenging as its Paris Resort.

Service delivery at Disney resorts and parks

The core values of the Disney company and, arguably,

the reason for its success, originated in the views and

personality of Walt Disney, the company’s founder. He had

Case study

Disneyland Resort Paris (abridged)

10

what some called an obsessive focus on creating images,

products and experiences for customers that epitomized

fun, imagination and service. Through the ‘magic’ of

legendary fairytale and story characters, customers could

escape the cares of the real world. Different areas of

each Disney Park are themed, often around various ‘lands’

such as Frontierland, and Fantasyland. Each land con-

tains attractions and rides, most of which are designed

to be acceptable to a wide range of ages. Very few rides

are ‘scary’ when compared to many other entertainment

parks. The architectural styles, décor, food, souvenirs and

cast costumes were all designed to reflect the theme

of the ‘land’, as were the films and shows. And although

there were some regional differences, all the theme parks

followed the same basic set-up. The terminology used by

the company reinforced its philosophy of consistent enter-

tainment. Employees, even those working ‘backstage’, were

called ‘cast members’. They did not wear uniforms but

‘costumes’, and rather than being given a job they were

‘cast in a role’. All park visitors were called ‘guests’.

Disney employees were generally relatively young, often

of school or college age. Most were paid hourly on tasks

that could be repetitive even though they usually involved

constant contact with customers. Yet, employees were

still expected to maintain a high level of courtesy and

work performance. All cast members were expected to

conform to strict dress and grooming standards. Applicants

to become cast members were screened for qualities such

as how well they responded to questions, how well they

listened to their peers, how they smiled and used body

language, and whether they had an ‘appropriate attitude’.

Disney parks had gained a reputation for their obsession

with delivering a high level of service and experience through

attention to operations detail. All parks employed queue

management techniques such as providing information

and entertainment for visitors, who were also seen as

Source: Corbis/Jacques Langevin

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 162

million Europeans visited the US Disney parks. The com-

pany’s brand was strong and it had over half a century

of translating the Disney brand into reality. The name

‘Disney’ had become synonymous with wholesome family

entertainment that combined childhood innocence with

high-tech ‘Imagineering’.

Initially, as well as France, Germany, Britain, Italy and

Spain were all considered as possible locations, though

Germany, Britain and Italy were soon discarded from the

list of potential sites. The decision soon came to a straight

contest between the Alicante area of Spain, which had

a similar climate to Florida for a large part of the year

and the Marne-la-Vallée area just outside Paris. Certainly,

winning the contest to host the new park was important for

all the potential host countries. The new park promised to

generate more than 30,000 jobs. The major advantage of

locating in Spain was the weather. However, the eventual

decision to locate near Paris was thought to have been

driven by a number of factors that weighed more heavily

with Disney executives. These included the following:

● There was a suitable site available just outside Paris.

● The proposed location put the park within a 2-hour

drive for 17 million people, a 4-hour drive for 68 million

people, a 6-hour drive for 110 million people and a

2-hour flight for a further 310 million or so.

● The site also had potentially good transport links.

The Channel Tunnel that was to connect England with

France was due to open in 1994. In addition, the French

autoroutes network and the high-speed TGV network

could both be extended to connect the site with the

rest of Europe.

● Paris was already a highly attractive vacation destination.

● Europeans generally take significantly more holidays

each year than Americans (five weeks of vacation as

opposed to two or three weeks).

● Research indicated that 85% of French people would

welcome a Disney park.

● Both national and local government in France were

prepared to give significant financial incentives (as were

the Spanish authorities), including an offer to invest in

local infrastructure, reduce the rate of value added tax

on goods sold in the park, provide subsidized loans,

and value the land artificially low to help reduce taxes.

Moreover, the French government was prepared to

expropriate land from local farmers to smooth the

planning and construction process.

Early concerns that the park would not have the same

sunny, happy feel in a cooler climate than Florida were

allayed by the spectacular success of Disneyland Tokyo in

a location with a similar climate to Paris, and construction

started in August 1988. But from the announcement that

the park would be built in France, it was subject to a

wave of criticism. One critic called the project a ‘cultural

Chernobyl’ because of how it might affect French cultural

values. Another described it as ‘a horror made of cardboard,

having a role within the park. They were not merely spec-

tators or passengers on the rides, they were considered to

be participants in a play. Their needs and desires were

analysed and met through frequent interactions with staff

(cast members). In this way they could be drawn into the

illusion that they were actually part of the fantasy.

Disney’s stated goal was to exceed their customers’

expectations every day. Service delivery was mapped and

continuously refined in the light of customer feedback and

the staff induction programme emphasized the company’s

quality assurance procedures and service standards

based on the four principles of safety, courtesy, show and

efficiency. Parks were kept fanatically clean. The same

Disney character never appears twice within sight – how

could there be two Mickeys? Staff were taught that cus-

tomer perceptions are both the key to customer delight,

but also are extremely fragile. Negative perceptions can

be established after only one negative experience. Disney

university-trained their employees in their strict service

standards as well as providing the skills to operate new

rides as they were developed. Staff recognition programmes

attempted to identify outstanding service delivery perform-

ance as well as ‘energy, enthusiasm, commitment, and

pride’. All parks contained phones connected to a central

question hotline for employees to find the answer to any

question posed by customers.

Tokyo Disneyland

Tokyo Disneyland, opened in 1982, was owned and oper-

ated by the Oriental Land Company. Disney had designed

the park and advised on how it should be run and it was

considered a great success. Japanese customers revealed

a significant appetite for American themes and American

brands, and already had a good knowledge of Disney

characters. Feedback was extremely positive with visitors

commenting on the cleanliness of the park and the

courtesy and the efficiency of staff members. Visitors also

appreciated the Disney souvenirs because giving gifts is

deeply embedded in the Japanese culture. The success of

the Tokyo Park was explained by one American living in

Japan. ‘Young Japanese are very clean-cut. They respond

well to Disney’s clean-cut image, and I am sure they had no

trouble filling positions. Also, young Japanese are generally

comfortable wearing uniforms, obeying their bosses, and

being part of a team. These are part of the Disney formula.

Also, Tokyo is very crowded and Japanese here are used

to crowds and waiting in line. They are very patient. And

above all, Japanese are always very polite to strangers.’

Disneyland Paris

By 2006 Disneyland Paris consisted of three parks: the

Disney Village, Disneyland Paris itself and the Disney Studio

Park. The Village was composed of stores and restaurants;

the Disneyland Paris was the main theme park; and Disney

Studio Park has a more general movie-making theme. At

the time of the European park’s opening more than two

Chapter 6 Supply network design

163

➔

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 163