Muller Eric L. American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

56 : the japanese american joint board

who had answered Question 28 on the registration questionnaire with an

unequivocal ‘‘no.’’) Of the remaining 4,000, Thurber explained, the wra had

granted indefinite leave to 3,200, or 80 percent. Captain Hughes responded

that he could not believe ‘‘that 4 out of 5 were let out,’’ and told Thurber that

he ‘‘could not understand why there would be such a di√erence of opinion

between the . . . [jajb] & wra.’’ Thurber explained that part of the di√erence

stemmed from the wra’s decision to hold individualized hearings in its

leave and segregation processes. Still, the military members of the Joint

Board found it ‘‘shocking’’ that the wra was reaching opposite conclusions

on loyalty in such a large number of cases.

∏π

Part of what may have made this realization so shocking to the military

members of the Joint Board was that the release of an internee on indefinite

leave was irrevocable. By midsummer 1943, the pmgo began to realize that

the wra was releasing some internees on indefinite leave before the jajb

had time to make a recommendation, and that as a result, there were Nisei at

liberty in places throughout the country about whom the Joint Board had

concerns about disloyalty. wra director Dillon Myer asked Attorney General

Francis Biddle what could be done about these internees: could the fbi pick

them up and return them to wra detention on the strength of an adverse

determination on indefinite leave by the jajb? The attorney general’s answer

was blunt. ‘‘I know of no legal authority to arrest and intern Japanese-

American citizens now residing outside of the evacuated military areas,’’ he

told Myer. ‘‘Therefore, I could not instruct the Federal Bureau of Investiga-

tion to apprehend and to return to relocation centers the individuals [already

released by the wra] after they have been released.’’ In other words, once the

wra released an internee on indefinite leave, he or she was free.

∏∫

The military members of the Joint Board learned of this at their meeting

on November 4, 1943, when ‘‘[i]t was pointed out . . . that the e√ect of this

letter [from the attorney general] was virtually to nullify unfavorable action

by the Board after an individual had been released.’’

∏Ω

In other words, if it

was not yet clear to the military members of the jajb, it became clear on

November 4, 1943, that the wra had the power to disregard the jajb’s

conclusions, and there was nothing the jajb or any other agency could do

about it.

But the revelation that the wra was allowing thousands of disapproved in-

ternees to leave the camps on indefinite leave was also undoubtedly ‘‘shock-

ing’’ to the military members of the jajb because they also knew that some of

those released internees were managing to land jobs in vital war plants. As

early as August 24, 1943, it was noted at a jajb meeting that although ‘‘[v]ery

the japanese american joint board : 57

few individuals ha[d] been released [from relocation centers] for war plant

employment, . . . they [were] get[ting] indefinite leave and migrat[ing] to the

big cities and get[ting] into war jobs’’ with the wra’s help and with ‘‘com-

plete disregard to the . . . [jajb’s] clearance [process].’’

π≠

Some military

members of the jajb worried that even though the Board had had no hand in

approving these former internees for work in war plants, the Board might

nonetheless ‘‘be held responsible for these cases’’ if things did not turn

out well.

π∞

Nisei workers in sensitive war plants without jajb approval were a matter

of especially grave concern for the pmgo, because war plant security was

one of the pmgo’s raisons d’être. By October of 1943, the pmgo had had

enough. A directive dated October 14, 1943, announced that all future ap-

plications from Nisei for approval to work in war plants would be investi-

gated by the relevant regional army service command and that the pmgo—

not the jajb—would have final authority to approve or disapprove all ap-

plications. The jajb would retain authority over only those internees whose

applications predated the October 14 directive.

π≤

As a technical matter, the

impact of this shift was not enormous: the pmgo’s Japanese-American

Branch had been shouldering most of the labor on the war plant cases while

the jajb had formal decision-making authority. Perhaps the most significant

impact was symbolic: the most notable thing about the shift was that the

War Relocation Authority lost even the modicum of influence on war plant

approvals that its single jajb vote had represented.

With the October 14 directive in place, the separation between the wra

and the pmgo became, in practice, complete. The e√ort to marry their

e√orts under the auspices of the jajb had come to naught. They were to have

cooperated on indefinite leave and war plant approvals. Yet in the matter of

indefinite leave from relocation centers, the wra retained, and exercised,

independent final authority; in the matter of war plant approval, the pmgo

had independent final authority. The wra and the pmgo remained under

the common roof of the jajb through May of 1944, when the jajb was

dissolved, but the agencies were more going through the motions of cooper-

ation than actually collaborating.

At times the collapse of collaboration on the jajb risked public exposure

in potentially mortifying ways. The most poignant illustration of this came

early in 1944, when the Board considered the idea of publicizing a story

about the good work that Nisei workers were doing in war plants. At the

Board’s meeting on March 2, 1944, Capt. John Hall read aloud an excerpt

from a confidential intelligence summary produced by the army’s Fifth Ser-

58 : the japanese american joint board

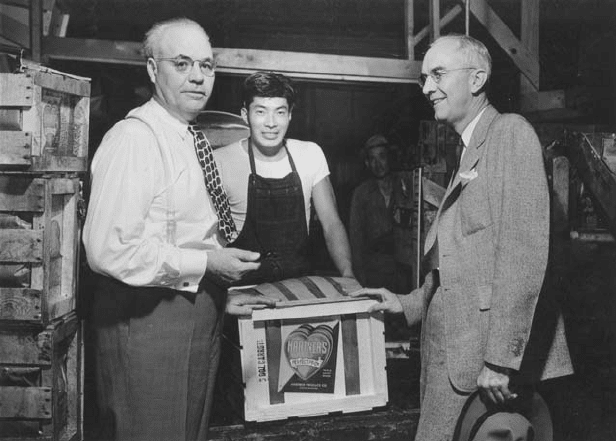

Ikuro Wada, granted indefinite leave by the War Relocation Authority from the Poston

Relocation Center in Arizona, at his produce-packing job in Denver, Colorado. On Wada’s left is

Dillon S. Myer, director of the wra. On Wada’s right is the owner of the produce-packing plant.

(Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1967.014 v. 35 EB-740.)

vice Command. Hall reported that during the month of January 1944, the

Cleveland Steel Products Company in Cleveland, Ohio, had employed eigh-

teen former internees between the ages of eighteen and twenty-two on its

production line. The company’s experience had been superb: the Nisei

‘‘were always constantly at their work and the absenteeism in the factory was

reduced to a minimum.’’ In addition, the company ‘‘ha[d] caught up to

production schedule,’’ and the Nisei’s outstanding work habits had ‘‘stimu-

late[d] the white people to real production.’’ Everyone on the jajb agreed

that ‘‘this would be a good article to print in the paper’’ and that no lesser a

figure than Interior Secretary Harold Ickes should issue the release.

π≥

Only one person at the meeting expressed any reservation about the plan,

and that was Capt. Clarence Harbert of the pmgo. Harbert suggested that

before publicizing this story about Nisei contributions at war plants, it

might be a good idea to make sure that all of the Nisei workers at the

Cleveland Steel Products Company had actually been cleared for war plant

work by the jajb.

π∂

The Fifth Service Command launched an investigation of

the situation at Cleveland Steel Products and learned that only four of the

the japanese american joint board : 59

eighteen Nisei employees had been cleared by the jajb for war plant employ-

ment. In addition, investigators learned that in the eyes of their white co-

workers, the Nisei had been too conscientious, and the whites had been

griping about it. The result of all of this was that Nisei productivity had

actually declined: the company’s owner reported that the Nisei were no

longer ‘‘producing as much as they [were] capable of because of labor

di≈culties and complaints from the Caucasians that their rate of production

[was] too high.’’

π∑

Captain Harbert therefore advised that ‘‘any attempt to publicize the

employment of persons of Japanese ancestry at the Cleveland Steel Products

Company, is not only very unwise but could very easily result in a dangerous

kick-back.’’

π∏

Not only would publicity reveal that Nisei workers were in

sensitive war plants without any sort of Joint Board clearance, but ‘‘any glory

given to the Japanese element could easily result in further and more compli-

cated labor di≈culties’’ among ‘‘the Caucasian employees of the firm.’’

ππ

The

Provost Marshall General’s O≈ce followed Harbert’s advice, recommending

to the O≈ce of the Assistant Secretary of War that the War Department

should give no publicity at all to the story of the hardworking Nisei at the

Cleveland Steel Products Company. And to add insult to injury, after further

investigation of the individual cases, the pmgo also ordered that two of the

conscientious Nisei steelworkers be fired for security reasons.

π∫

The rift between the wra and the military members of the jajb led not

only to potentially embarrassing public disharmony but also to angry re-

crimination. So dour were the military’s views of the War Relocation Author-

ity that evidence of vituperation surfaces even in the jajb’s o≈cial written

minutes. In the minutes of the meeting of July 29, 1943, in the midst of

agenda items concerning ordinary Joint Board business, the following item

appears: ‘‘4. Criticism of wra by the Joint Board. The Joint Board was in

complete agreement with Mr. Holland [of the wra] that it was not a proper

function of the Joint Board to criticize wra operations, except insofar as

they related to the activities of the Joint Board.’’

πΩ

The minutes do not reflect

what the military members of the Board had been caught saying, or to

whom, but it must have been extreme in order to earn a mention at a jajb

meeting, let alone inclusion in the o≈cial record of the Joint Board’s

proceedings.

Once the Joint Board’s work was done, neither the War Relocation Au-

thority nor the pmgo shied away from publicly criticizing the other. The

wra, for its part, was at least modestly circumspect in its public statements.

In a report on the wra’s relations with other government agencies that wra

60 : the japanese american joint board

director Dillon Myer wrote in 1946, he said that on ‘‘matters a√ecting re-

straints’’ on Japanese Americans, War Department o≈cials were ‘‘generally

arbitrary.’’

∫≠

Similarly, in its final report, the wra argued that while the

O≈ce of the Assistant Secretary of War played a constructive role on the

jajb, ‘‘some other sta√ members of the War Department and of the Western

Defense Command . . . succeeded in distorting the functions of the Board

rather badly.’’

∫∞

In a private interview in January of 1945, Myer was consider-

ably more caustic, fuming that the pmgo’s entire approach was ‘‘unneces-

sary and . . . gumming up the works,’’ a silly system of ‘‘running IBM cards

through machines and totaling arbitrarily such weighted factors as educa-

tion in Japan, ‘No No’ answers, repatriation requests, fbi reports,’’ and the

like. Myer told his interviewer that he thought this ‘‘canned’’ system, with its

‘‘big room full of cards,’’ was ‘‘nonsense.’’

∫≤

The Japanese-American Branch of the pmgo, by contrast, was anything

but circumspect in its final assessment of the wra. The wra, complained

the Japanese-American Branch in its final report, ‘‘was sta√ed largely with

trained social workers who could not become war minded even tempo-

rarily.’’ The wra was, in the Japanese-American Branch’s view, ‘‘a civilian

agency whose personnel and exponents of civil liberties have read only that

portion of our constitution dealing with the Bill of Rights,’’ and who had left

‘‘the wartime powers provided in other sections of that document . . . either

. . . ignored or unscanned.’’ ‘‘With plenty of moral and political support from

higher authority and pacifist and non-war-winning groups in our country,’’

the wra had ‘‘winked at War Department regulations and deliberately

placed Japanese in employment and positions contrary to the provisions of

specific regulations and when the War Department sought to take appropri-

ate action, pleaded the constitutional guarantees to citizens.’’ The wra never

‘‘volunteer[ed] to assume one iota of the security burden’’

∫≥

shouldered by

the War Department and ‘‘was non-cooperative in any program created by

security regulations.’’ ‘‘It had,’’ alleged the Japanese-American Branch,

‘‘breached its responsibilities of reasonable cooperation and fair dealing.’’

∫∂

In the wra’s work with the jajb, groused the pmgo’s Japanese-Ameri-

can Branch, the civilian agency ‘‘was permitted to pass responsibility to the

Board for the release of all persons favorably recommended, but was permit-

ted to completely ignore any adverse recommendations by the Board based

upon derogatory information as to [an internee’s] loyalty.’’ Most damagingly

of all, the Japanese-American Branch alleged, the wra had managed to

‘‘force’’ the military personnel on the jajb into ‘‘acced[ing] to the demands

the japanese american joint board : 61

of wra’’—‘‘concessions’’ that ‘‘resulted in compromises as to the loyalty of

individuals.’’

∫∑

This was harsh criticism indeed.

Loyalty and Disloyalty According to the JAJB

According to the pmgo, wra pressure led the jajb to compromise na-

tional security by approving the release and employment of Nisei who were

not loyal to the United States. This is a view that hindsight allows us to test.

If the pmgo was right, and the jajb was too lax, it would stand to reason

that at least a few dangerous Nisei would have slipped out of the camps and

into the nation’s war plants. Yet there was not a single reported incident of

industrial sabotage by a Japanese American anywhere in the United States

during World War II. Indeed, with the exception of one instance in which

three Nisei sisters helped two German war prisoners escape from their

Colorado POW camp,

∫∏

there was not a single reported incident of any sort of

sabotage or subversion by a released Japanese American internee anywhere

in the United States during or after World War II.

As a logical matter, this whistle-clean record could be taken as proof of

absolute precision in the jajb’s screening methods. Perhaps the camps held

scores of Nisei saboteurs, and the jajb got things exactly right, frustrating

the plans of every single one of them by forbidding them access to war

plants. Perhaps every single one, or the majority, or even just a healthy

minority of the more than 12,000 Nisei for whom the Joint Board entered

adverse loyalty findings really were spies and saboteurs, and the Board judi-

ciously recommended against their release. In practice, though, this seems

quite unlikely. The template that Calvert Dedrick designed for the Board was

so wooden, so skewed toward the sorts of outward signals of Japanese

cultural a≈liation that any true subversive would avoid, and so ridiculously

oversimplified that the system simply could not have worked that accurately.

The fairer inference is that the jajb very often got things wrong.

A look at a few of the human lives touched by the Joint Board’s errors

supports this inference.

∫π

Harry Iba

Harry Hayao Iba was born in Los Angeles to Issei parents on November

11, 1915.

∫∫

His family was Buddhist. He never traveled to Japan in his child-

hood and did not hold dual citizenship. He never attended a Japanese after-

school program, and described his spoken Japanese as ‘‘fair.’’ He could

write and read the language only poorly. He graduated from high school in

62 : the japanese american joint board

1934 and went to work in the family nursery business. He had a brother in

the U.S. Army and a brother in medical school in Boston whose tuition he

helped pay.

He subscribed to the Los Angeles Times, the Examiner, Reader’s Digest, Time,

Life, Sunset, and Popular Mechanics. He liked to play football, ping-pong, and

outdoor sports. He collected camellia plants. On his registration form, he

said that he would serve in the U.S. armed forces if drafted and answered

‘‘yes’’ to Question 28, which asked about his willingness to forswear alle-

giance to the emperor of Japan or other foreign powers. His attorney, land-

lord, and neighbors in Los Angeles—all of them white—wrote glowing ref-

erence letters for him. His lawyer said he was ‘‘as loyal to America as any

Japanese could be’’—an ‘‘honest, intelligent, respectable, law abiding cit-

izen.’’ ‘‘He is extremely honest and his word means much,’’ said his former

landlord, adding that he was ‘‘a credit to our neighborhood.’’ He was ‘‘100%

American,’’ said family friend Larry Keary, certain to ‘‘pass every test for

loyalty and sincerity.’’ To his landlord, he and his family were ‘‘excellent

tenants and good neighbors.’’

On his registration form, he indicated that he had no account in foreign

banks and no investments in foreign countries. He also wrote that in 1937,

when he was twenty-two, he traveled to Japan with ‘‘a group of boys for

personal reasons’’ on the ship Taiyo Maru. At a wra leave clearance hearing

at the Amache Relocation Center, he explained that the trip was a sightseeing

trip with his judo club. He was also told at the hearing that a record search

had turned up an account in his name at the Los Angeles Sumitomo Bank in

the amount of 591 yen (about $147), a joint account with his mother at the

same bank in the amount of 11,090 yen (about $2,977), and a trust account in

his name, with his mother as trustee, in the amount of 1,669 yen (about

$417). This surprised Iba; he said that he ‘‘didn’t know anything about it

unless my family deposited this money in to me when I was a small tot.’’

‘‘You know how mothers are,’’ Iba said, ‘‘you know how she saves it for you,

then if you get hard up it comes up some place. She won’t tell you until you

need it.’’

At its meeting on August 19, 1943, over the dissent of the wra represen-

tative, the jajb recommended indefinite confinement for Harry Iba.

∫Ω

Hiroshi Hishiki

Hiroshi Hishiki was born in Los Angeles to Issei parents on April 17,

1918.

Ω≠

He did not hold dual citizenship. His father, a manufacturer, had

arrived from Japan in 1902, his mother in 1914. Hishiki was a Protestant and

the japanese american joint board : 63

a member of St. Mary’s Church, the Brotherhood of St. Andrews, and the

ymca. He received all of his education in the United States, graduating from

ucla in 1940 with rotc training and a major in business administration.

He registered to vote in 1941 as a Democrat. He worked in his father’s

handkerchief manufacturing business and, by the time of his family’s exclu-

sion from the West Coast in 1942, was running the business because his

father was ill. He enjoyed photography, basketball, and tennis and sub-

scribed to the Los Angeles Times, Life, Reader’s Digest, and Newsweek.

Hishiki traveled with his parents to Japan in 1932 to visit his grandparents

and great-aunts and great-uncles. He attended Japanese language school in

the United States for nine years as a child and spoke the language well

enough to work as a teacher at the Los Angeles Nippon Institute, a Japanese

language school. His salary was $6 per month. He explained at his wra

leave clearance hearing that he taught once a week, on Saturdays, and that

teaching gave him the chance to maintain his own language skills. The

school’s principal, a Mr. Yoshizumi, was an Issei who had been in the

Japanese army in the past and who was interned as an enemy alien some

months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. On December 8, 1941, when the

U.S. government froze the bank accounts of all Issei and Japanese organiza-

tions in the United States, Hishiki became the treasurer of the Nippon

Institute’s Alumni Association and occasionally withdrew small subsistence

payments for Mr. Yoshizumi. Over the months following Pearl Harbor, these

payments amounted to between $200 and $300 out of the $2,000 in the

alumni account.

On his registration questionnaire, Hishiki avowed his loyalty to the

United States on Question 28. On Question 27, which asked whether he

would agree to serve in the armed forces of the United States, he wrote ‘‘no,

unless social conditions change to satisfaction or unless drafted.’’ At his

leave clearance hearing, he explained that as an only son, he ‘‘had parents

that were ill, and relatives that had been interned,’’ and he believed that ‘‘if

[he] were drafted there would be no one to take care of them in case some-

thing happened.’’ This was what he meant by ‘‘social conditions’’: he could

not envision himself in the service unless he knew his family would be cared

for. Asked whether he would have any objection to going into the service if

he were drafted, he replied, ‘‘If I were drafted, it would have to be.’’ He said

he preferred not to fight the Japanese army because ‘‘there is a certain

amount of mixed feeling when you are fighting your own blood,’’ but ‘‘if

there were no choice,’’ he would serve. When asked whom he would like to

see win the war, Hishiki replied, ‘‘Naturally this country,’’ because ‘‘I was

64 : the japanese american joint board

born in this country, have been to Japan and I know what it is like and I still

feel that my place is over here.’’

At its meeting on August 19, 1943, the jajb recommended indefinite

confinement for Hiroshi Hishiki.

Ω∞

The wra representative dissented.

Dorothy Ito

Dorothy Ito was born on January 20, 1909, to Issei parents in Betteravia,

California.

Ω≤

She was not a dual citizen. Her family, which included a sister

and seven brothers, was Buddhist. She neither traveled to Japan nor attended

a Japanese after-school program in the United States, so she could neither

read nor write Japanese. Her spoken Japanese was poor. She liked to read the

Los Angeles Times, Reader’s Digest, Life, Look, and Ladies’ Home Journal. She was

unmarried and never registered to vote. One of her brothers was in the U.S.

Army, having joined before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. She an-

swered ‘‘yes’’ to both Questions 27 and 28 on her registration form.

Ito’s father was interned after Pearl Harbor because of involvement in

several Japanese organizations in the late 1930s, but Ito knew nothing of his

activities because she had left home in 1936. Ito’s mother was stricken with

brain cancer in the late 1930s and was an invalid in critical condition by the

time of the evacuation of the Japanese from the West Coast in the spring of

1942. It was Ito’s job to provide her mother with round-the-clock care. In

April of 1942, Ito’s mother was moved to the Sisters’ Hospital in Santa

Maria, California, and Ito moved in to the hospital to care for her.

Because Ito feared that her mother would not survive evacuation, she

sought to keep her in the hospital in California as long as she could. By the

end of 1942, however, the government insisted that she and her invalid

mother had to leave the Western Defense Command. Because her brother

was in the army, Ito ‘‘made a lot of requests that [her family receive] a little

consideration about . . . being pushed around here and there.’’ She even

pressed her brother in the army to ask his commanding o≈cer to help them.

But all of her requests were in vain. In January of 1943, Ito was forced to

take her critically ill mother to the Gila River Relocation Center in Arizona.

She asked that the government defray the costs of the move, but the govern-

ment did not. She had to pay for the move out of her own pocket. As late

arrivals at Gila River, Ito and her mother found themselves without many

basic necessities. Ito spent her first six months at Gila River without even

receiving a basic clothing allowance.

The hospital at Gila River was not set up to accommodate patients for

long-term care, so Ito had to care for her mother by herself in their camp

the japanese american joint board : 65

barrack. The hospital would care for Ito’s mother only during acute epi-

sodes, and when her mother stabilized, the hospital would return her to her

barrack.

On January 21, 1944, the O≈ce of Naval Intelligence (oni) reported to the

War Relocation Authority that ‘‘[t]here [were] indications that the subject had

attempted to discourage [her brother] from doing his [military] duty as a

loyal citizen of this country.’’ The oni also reported an allegation that Ito

‘‘had . . . expressed strong animosity against the United States Government

and also a strong personal contempt and dislike of one Dr. Sleath, the

supervisor of the hospital at the Gila River Relocation Center.’’ The first

allegation appears to be someone’s uncharitable interpretation of the pres-

sure that Ito placed on her soldier brother to get the help that Ito felt the

government owed a military family. And after a leave clearance hearing, a

wra o≈cial concluded that the second allegation of an ‘‘outburst’’ at the Gila

River Hospital was ‘‘adequately explained’’ as ‘‘an emotional reaction result-

ing from [Ito’s] mother’s invalid condition, and the cares placed on her.’’

The jajb did not agree. At its meeting on February 2, 1944, it ruled that

Dorothy Ito should remain in confinement.

Ω≥

The stories of Harry Iba, Hiroshi Hishiki, and Dorothy Ito put a human

face on the jajb’s adjudications of the loyalty and disloyalty of Japanese

Americans. But it is important to remember that the jajb’s review process

was not about human stories. The Board had neither the time nor the inter-

est to consider the life stories of the individuals before it, more than half of

whom it evaluated on the basis of nothing more than their answers on a

registration questionnaire.

Ω∂

The cases were ‘‘white’’ cases or ‘‘brown’’ cases

or ‘‘black’’ cases, and if they were brown, then what mattered was which

pairs of ‘‘ham-and-eggs’’ factors they revealed, or which configuration of

items from the ‘‘Chinese menu’’ of Japanese American loyalty they pre-

sented. What mattered were Calvert Dedrick’s templates—mechanical de-

vices that made an internee’s perceived cultural identification with Japan—or

that of his male relatives—into a proxy for disloyalty and danger to national

security.