Lowenthal G., Airey P. Practical Applications of Radioactivity and Nuclear Radiations

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

6.2 Glaciology

Ice cores dated and

provide an archival

record of global

temperatures and the

levels of `green-house'

gases

Stable isotopes D/H

18

O/

16

O (temperature

and dating) and

14

C

techniques correlated

with the analyses of

gases from ice cores

Accelerator Mass

Spectrometry (AMS)

essential as small samples

normally only available

Information on past climate

also from sediment cores

7.1

Nuclear waste disposal

Natural analogues of

waste repositories

Validation of

performance

assessment models

over long time scales

Possible impact of the

leakage of

radionuclides on

future generations

Uranium ore bodies as

analogues of spent

reactor fuel in waste

repositories

Uranium series nuclides,

e.g.

234

U/

238

U,

230

Th/

234

U,

226

Ra/

230

Th isotope ratios

in host rock and

groundwater near a deposit

used to validate aspects of

radionuclide transport

models

initial values of the activities at the time when the samples were formed; (c)

calculation of the age of the sample from the mathematical relationship linking

the initial and the measured values.

Dating techniques are most reliable when, as in the case of carbon-14, the age

of a specimen is determined by the decay of a single isotope. If, on the other

hand, the isotope is a member of a decay chain, the build-up and de cay of the

parent (Section 1.6.2) may also nee d to be taken into account. The interpreta-

tion is usually more complex and so are the measurements. A large number of

techniques for the dating of geological samples have been developed (Geyh and

Sleicher, 1990). Although geochronology is outside the scope of this book,

Table 9.2 contains a list of the commonly used dating methods.

The second stage of the archival approach involves measurement of indica-

tors of environmental change in the dated samples. For instance, the systematic

monitoring of levels of heavy metal pollutants in dated sediment or coral cores

may provide important information on the history of ef¯uent release in the local

region. Again, systematic variations in the

18

O/

16

O and D/H ratios in ice cores

re¯ect changes in global temperature and therefore in global climate. Several

applications are discussed in more detail in Section 9.3.

9.2 The investigation of environmental systems

9.2.1 Numerical modelling

Environmental investigations have traditionally involved a combination of

data gathering and scienti®c interpretation. In more recent times, computing

has developed to the extent that a third element, numerical modelling, is of

comparable signi®cance. Its impact has been greatly enhanced by parallel

developments in the visualisation of data. Reference need only be made to

modern graphical representations of results obtained in the laboratory and in

the ®eld, as well as the visualisation of satellite images and the output of

numerical codes. Spectacular examples of the latter include the visualisation

of global climate change models and ocean circulation models.

The rapid growth in the use of numerical codes has led to a shift in the role

of tracer techniques. As with industrial applications, tracers are now used less

for the investigation of particular processes, and more for model validation.

To illustrate this point, reference will be made to studies of contaminant

dispersion in Section 9.3.3.

Many environmental systems cannot be modelled satisfactorily, either

because they are inherently too complex or because too little is known of the

underlying physical processes. In such cases statistical or correlation techni-

ques are often helpful in establishing the relative importance of different

Radionuclides to protect the environment272

Table 9.2.

Environmental radioisotopes

.

Isotope Source Half life Analysis Application

Comments

H-3

(tritium)

Atmospheric

testing

cosmogenic

12.3 y

b counting

(liquid

scintillation,

Section 5.4.2)

Groundwater

recharge.

Oceanographic

mixing

Environmental tritium dominated by

atmospheric testing source; hence tritium in

water implies that a component of the

water from post-nuclear i.e. post-1950

precipitation. Environmental tritium is

used to identify groundwater recharge

(Section 9.4.3) areas and to study

oceanographic surface mixing processes

(Section 9.4.4)

Be-7 Cosmogenic 53 d

g spectrometry

at 480 keV

(Section 6.4)

Sediment

accumulation

and

redistribution

over the

previous half

year

The technique for Be-7 counting is similar

to that for Cs-137 counting (Section 9.4.2).

The samples are dried, weighed, placed in a

Narinelli beaker over a high-resolution

detector and the 480 keV gamma peak

measured (see Section 9.4.1)

The presence of Be-7 in a sediment core

indicate that the material has been at the

surface over the past six months. Be-7 is

correlated with Cs-137 in sediment cores

which provides information on the rate of

accumulation of sediment in post nuclear

times i.e. over the past 40 years

Be-10 Cosmogenic 1.6

610

6

y AMS

Be-10 is used to study sediment

accumulation and redistribution over the

past few million years. Where possible, it is

used in association with Al-26

Table 9.2.

(cont.)

Isotope Source Half life Analysis Application

Comments

C-14 Atmospheric

testing

5730 y

AMS, b

counting

Post-nuclear

processes

(hydrology,

oceanography)

In post-nuclear times, atmospheric nuclear

testing is the major source of C-14. It

therefore exhibits a typical `bomb' pulse

which has been used, for example:

&

to study the uptake of CO

2

by the oceans;

&

to investigate mixing processes in the

upper layers of the oceans in post-

nuclear times;

&

to study the incorporation of

atmospheric CO

2

into antarctic ice ®rn in

order to re®ne the C-14 age dating of ice

cores; and

&

to provide independent evidence of the

source of carbon (modern vegetation or

mineral) in commercial products should

it be contested

Cosmogenic

Pre-history;

evolution of

coastal and

other ecological

systems in recent

geological time;

global climate

change studies

C-14 is used for dating carbon containing

materials up to 50 000 y. The technique has

been widely used for:

&

dating artefacts, bones and charcoal and

thereby making a major contribution to

an understanding of pre-history and the

evolution of ecological systems;

&

studying groundwater ¯ow patterns;

&

investigating coastal processes through,

for instance, the dating of marine corals,

of shell grit in dunes and of sediments in

estuaries and lakes;

&

better understanding of global

oceanographic circulation patterns; and

&

dating of tree rings, ice cores and corals

as a contribution to global climate

change studies

Al-26 Cosmogenic 740 000 y AMS

Erosion and

sedimentology

Al-26 together with Be-10 is used to study

the rate of accumulation of sediments and

of the erosion of exposed rocks over

millions of years

Cl-36 Atmospheric

testing

Cosmogenic

301 000 y AMS

Salinity,

groundwater

quality

Dating of old

groundwater

The Cl-36 bomb pulse is used to chloride

migration i.e. salinity processes in the

unsaturated zone and in modern

groundwater

Cl-36 is used to date groundw ater up to one

million years old. More generally it is used

to study aspects of the chloride cycle, i.e.

the evolution of groundwater quality

Cs-137 Atmospheric

testing

30.1 y

g spectrometry Sedimentation,

soil erosion

Cs-137 is used to measure the rate of

sedimentation and erosion in post-nuclear

times. Please refer to Section 9.4.2 and to

Table 9.1

Th-232

U-238

U-235

Primordial

Primordial

Primordial

1.4610

10

y

4.47610

9

y

7.0610

8

y

a spectrometry,

Mass

spectrometry

Dating

geological

samples

Th-232, U-238 and U-235 are the

progenitors of Pb-208, Pb-206 and Pb-207

respectively. They are used to date old

geological material of age up to 10

9

years or

more. Ion microprobe methods are

available to date individual inclusions

within natural materials and have been

widely applied to the dating of zircons

Table 9.2.

(cont.)

Isotope Source Half life Analysis Application

Comments

U-234

Th-230

U series

U series

245 500 y

75 380 y

g±X

spectrometry,

Thermal

Ionisation Mass

Spectrometry

Uranium

migration; age

sedimentary U

deposits

Dating

sediments and

corals

234

U/

238

U ratios are measured in

geochemical samples and groundwater.

Together with other data they are used to

study the dissolutio n, migration and

deposition of uranium. Applications

include the age and stability of uranium

deposits

230

Th/

234

U activity ratios have been widely

used for the dating of the accumulation of

sediments in estuaries and to the dating of

massive corals (e.g. porites)

Ra-226 U series 1601 y

g±X

spectrometry

Radium-226 is the parent of radon-222

Rn-222 U series 3.83 d

The level of radon in houses and in

drinking waters is extensively monitored

since it could be a signi®cant source of the

annual radiation dose received by the

general public (Table 2.5)

Radon is emitted from the soil and is a

natural tracer for air masses which have

passed over land within the preceding few

days. Air masses which have not `seen' land

for a few days are much lower in radon.

Their levels are measured in a number of

reference stations and contribute to the

validation of atmospheric circulation

models and hence to climate change studies

Pb-210 U series 22.2 y

Sediment dating

over the past

100 y

The

210

Pb method has been extensively

applied to the dating of sediments in lakes

and estuaries over the past 100 years. The

sediment is cored and individual sections

assayed for

210

Pb. There are two

components of

210

Pb, the unsupported and

the supported. The unsupported lead,

which is used in measuring the

accumulation rates, is adsorbed on the

surface from the decay of the

222

Rn

dissolved in the associated water. The

supported

210

Pb is derived from the decay

of the

238

U within the sediment minerals.

Experimentally, the supported lead is

calculated from the measured uranium

levels, and is subtracted from the total to

obtain the `unsupport ed' component

parameters. For instance the rate of erosion depends on a wide range of

factors including the intensity and distribution of rainfall patterns, the

properties of soils and the nature and coverage of vegetation. The most

widely used equation for estimating soil erosion is the Universal Soil Loss

Equation (USLE), which was developed for soils east of the Rocky Moun-

tains in the United States (Wischmeier and Smith, 1965). As discussed in

Section 9.4.2 this equation has often been used in settings where it does not

strictly apply. Some form of validation is essential. In this case, the distribu-

tion of environmental isotopes such as the fall-out product

137

Cs may be used

to provide additional independent measurements of erosion rates at different

points within a catchment. Such information can be used to re®ne the

correlation equations and enhance their predictive value.

9.2.2 Applications of radioisotopes

Both man-made and naturally occurring radioisotopes are used extensively in

environmental science. Many applications of the former have evolved out of

analogous studies of industrial processes discussed in Chapter 8. For

instance, the use of tracer dilution techniques for ¯ow rate measurements

which were developed for pipeline studies (Section 8.3.2) have been widely

applied to the gauging of rivers and streams (Section 9.3.2).

Naturally occurring radionuclides, also known as environmental radio-

nuclides, are classi®ed into three sub-groups according to their source ±

cosmogenic radioisotopes, `fall-out' products and primordial isotopes.

1. Cosmogenic radioisotopes notably tritium, beryllium-10, carbon-14 and

chlorine-36 are generated principally in the upper troposphere and lower strato-

sphere by the impact of cosmic rays on the components of the residual

atmosphere. They subsequently diffuse to the surfa ce of the land and the oceans

either with rainfall or associated with particulates.

2. Fall-out products result from past nuclear testing in the atmosphere. They

include a range of ®ssion products, such as caesium-137 as well as tritium,

carbon-14 and chlorine-36 which are also cosmogenic isotopes. Their yields

reached a maximum in the mid-1960s prior to the Atmospheric Test Ban Treaty

and then decreased. This pattern is often observable in environmental systems

and is referred to as the `bomb pulse'.

3. Primordial isotopes such as uranium-238, thorium-232 and their daughters (Figure

1.5) have been present since the formation of the earth. The stable isotopes

deuterium, carbon-13 and oxygen-18 could also be included wi thin this group.

Each class of radionuclides has particular features which may be exploited in

the design of an environmental investigation. For instance, studies involving

Radionuclides to protect the environment278

arti®cial radioisotopes can be precisely tailored to particular processes. A

number of examples are presented in Table 9.1. On the other hand environ-

mental isotopes are widely distributed tracers and can be used to study the

cumulative effects of processes over a wide geographic area (Table 9.2).

Accessible time scales vary widely depending on the half life of the isotope

and the sensitivity with which it can be measured. Of course, fall-out products

are the exception as they only entered the environment in post-nuclear times.

9.3 Environmental applications of radioisotopes

9.3.1 Introduction

Applications of reactor-produced radioisotopes to industry were discussed in

Chapter 8 and listed in Table 8.3. As noted in Section 8.1.3, some of the

earliest environmental applications of tracers were to the measurements of

river ¯ow, sewage dispersion and sand and sediment migration.

Radioisotope investigations are becoming increasingly sophisticated, re-

quiring precise quantitative data. Procedures for accurate activity measure-

ments in laboratories were discussed in Sections 6.3 and 6.4. As a rule, the

calibration of ®eld detectors also has to be done in the laboratory when it is

often dif®cult to reproduce the counting geometry used in the ®eld. The

calibration of detectors for river ¯ow and sand transport measurements is

discussed in Sections 9.3.2 and 9.3.5 respectively.

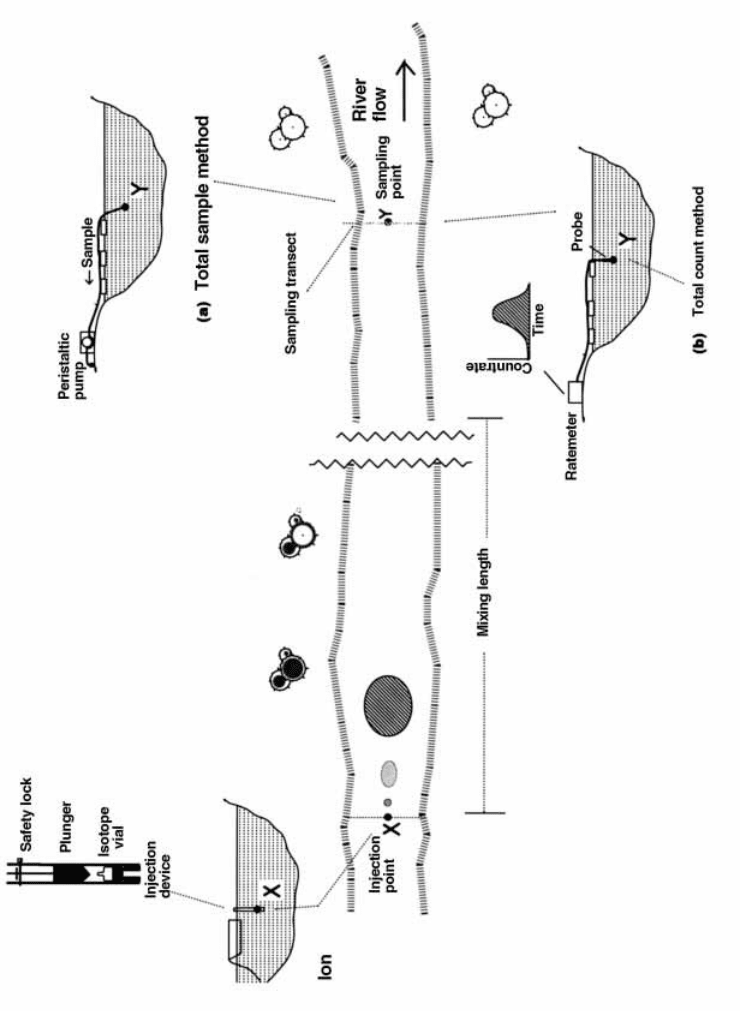

9.3.2 River ¯ow measurements

The total sample method using tritium

The application of tracer dilution techniques to the measurement of ¯ow

rates in industry was discussed in Section 8.3. Reference was made to the

total sample and the total count techniques. Both methods have been applied

extensively to the gauging of rivers and streams. The principle is illustrated in

Figure 9.1(a). The isotope is injected as an instantaneous pulse at X and, after

complete mixing has been achieved, the plume is monitored at a convenient

sampling point Y.

Chemically, tritium as HTO is the `perfect' tracer for water. Furthermore,

it can be easily transported in a sealed glass vial, and requires a minimum of

shielding. Care must be taken to ensure that investigators do not inhale any

tritiated water vapour when releasing the tracer into the river, but such a

precaution is readily achieved. Experimental procedures are designed to be as

9.3 Environmental applications of radioisotopes 279

Figure 9.1. The gauging of rivers using dilution methods following

the instantaneous release of the radiotracer with the injection

device (bottle breaker). The cross sections at the injection and sampling

transects

X and Y are shown. (a) Total sample method: a

sample is collected at an accurately known rate and the activity measured.

(b) Total count method: the detector is immersed in the

river and the total counts recorded during the passage of the plume.