Lima J.J.Pedroso, de (ed.). Nuclear Medicine Physics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

8 Nuclear Medicine Physics

Fundamental dosimetric quantities are defined: particle and energyfluence,

kerma, and absorbed dose. Due to the biological risks, more specific quan-

tities, known as radiological quantities, are required, namely the radiation

weighted dose (previously the equivalent dose) and the effective dose. Other

radiological quantities with biophysical relevance are presented, such as LET,

relative biological effectiveness (RBE), and the quality factor as a function of

LET; and reference is made to radiation and tissue weighting factors.

From a theoretical point of view, radioactive decay, radiation attenuation,

and radionuclide biokinetics have a formal and mathematical identity result-

ing from the presence of first-order equations. Radionuclide dosimetry is

basically developed by considering topics such as activity and strength of

source and the linear differential equation model of attenuation and scat-

tering. The concept of point source is generalized to the point-kernel concept

with application to a linear source as a superposition of point sources. Surface

and volume sources are also considered. For internal dose assessment, basic

concepts such as the air–kerma rate constant, source and target organs, and

the committed effective dose are presented; and one-compartment radionu-

clide biokinetic models are used. Procedures for internal dose assessment,

using Medical Internal Radiation Dose (MIRD) and International Commis-

sion on Radiological Protection (ICRP) models, are presented. The overall

dosimetry for carbon-11-labeled tracers is estimated, which can be general-

ized to cover individual probes. Mathematical methods of cellular dosimetry,

which are mainly concerned with electron dosimetry and the application of

electron point kernels, are presented. In addition, the concepts of cross-dose

and self-dose at cellular level will be introduced, together with other relevant

mathematical aspects such as the geometric factor. As a modern approach to

radiation dosimetry, the Monte Carlo approach is briefly reviewed.

The mechanisms of the biological action of ionizing radiation, specifically

on DNA actions that will induce double-strand breaks and on the conse-

quences of these events on the development of chromosome alterations, are

then analyzed.

The following target-hypotheses (target-theory models) are considered:

1. One sensitive region, n hits

2. Multiple sensitive sublethal regions/one hit

3. Mixed model

4. Linear–quadratic model (L–Q)

Target theory and L–Q models are compared.

Finally, low-dose nontargeted effects complementary to the direct action of

ionizing radiation are introduced.

2

Cyclotron and Radionuclide Production

Francisco J. C. Alves

CONTENTS

2.1 The Quantitative Aspects of Radionuclide Production .......... 10

2.1.1 Nuclear Reactions ................................ 11

2.1.2 Cross Section ................................... 15

2.1.3 Excitation Function ............................... 16

2.1.4 Excitation Function and Radionuclide Production ........ 16

2.1.5 Ion Kinetic Energy Degradation in Matter Interaction ..... 19

2.1.6 Stopping Power: Bethe’s Formula .................... 20

2.1.7 Range ......................................... 22

2.1.8 Straggling: Statistical Fluctuation in Energy Degradation . . . 23

2.1.9 Energy Degradation versus Ionization ................. 25

2.1.10 Thick Target Yield ................................ 26

2.1.11 Experimental Measurement of the Excitation Function: The

Stacked Foils Methodology ......................... 28

2.2 The Cyclotron: Physics and Acceleration Principles ............ 32

2.2.1 Introduction and Historical Background ............... 33

2.2.2 The Resonance Condition .......................... 35

2.2.3 Magnetic Focusing ............................... 38

2.2.3.1 Axial Focusing ............................ 38

2.2.3.2 Radial Focusing ........................... 40

2.2.3.3 Stability Criteria ........................... 42

2.2.3.4 Free Oscillation Amplitude ................... 44

2.2.4 Electric Focusing ................................. 46

2.2.4.1 Introduction .............................. 46

2.2.4.2 Static Focusing ............................ 47

2.2.4.3 Dynamic Focusing ......................... 48

2.2.4.4 Combining the Focusing Effects ............... 48

2.2.5 Phase Relations and Maximum Energy ................ 50

2.2.5.1 Path and Phase in the First Revolutions ......... 50

2.2.6 Maximum Kinetic Energy: The Relativistic Limit ......... 54

2.2.7 The Synchrocyclotron ............................. 57

2.2.7.1 Working Principle ......................... 57

2.2.7.2 Phase Stability ............................ 57

9

10 Nuclear Medicine Physics

2.2.8 The Isochronous Cyclotron ......................... 58

2.2.8.1 Thomas Focusing and Working Principle ........ 58

2.2.9 Focusing Reinforcement Using the Alternating

Gradient Principle ................................ 60

2.2.10 Aspects of Quantitative Characterization ............... 62

References .............................................. 65

2.1 The Quantitative Aspects of Radionuclide Production

The radionuclei that lead to different nuclear medicine techniques are not

readilyavailable in nature and need to be producedthrough nuclear reactions.

The main fundamental physics mechanisms used in radionuclide production

are fission, neutron activation, and particle irradiation. Fission and neutron

activation are performed in nuclear reactors. Exposing Uranium-235 to ther-

mal neutrons produced in a nuclear reactor can induce the fission of the

uranium isotope, resulting in low (usually between 30 and 65) atomic number

nuclei. Some of the nuclei produced in this way can be chemically separated

from other fission fragments and are widely used in biomedical sciences, par-

ticularly in nuclear medicine. Fission is used, for instance, in Molybdenum-99

production, through the nuclear reaction

235

U +n →

236

U →

99

Mo +

132

Sn +4n.

Neutron capture activation is another production process that can be per-

formed in a nuclear reactor. The following nuclear reactions are important

examples of this mechanism, as used in the production of Molybdenum-99

and Phosphor-34, respectively:

n +

98

Mo →

99

Mo +γ,

n +

32

S →

32

P + p.

Particle irradiation, leading to nuclide transmutation, is performed in a

cyclotron. A target material is irradiated with accelerated particles (protons,

deuterons, and in some cases, α particles), leading to a nuclear reaction. This

type of nuclear reaction, induced by cyclotron beam particle irradiation, can

be generically described using Bothe’s notation:

A(a, b)B

The target nucleus appears before the first bracket and the resulting nucleus

after the final bracket. Inside the brackets, the irradiating and emitted particles

are separated by commas.

Cyclotron and Radionuclide Production 11

This chapter focuses mainly on the physical mechanisms involved in

cyclotron radionuclide production, given the widespread use of this accelera-

tor in nuclear medicine centers—particularly those using PET—as opposed to

nuclear reactors, which continue to be located in specialist central laboratories

outside the clinical or hospital environment. Nevertheless, the main con-

cepts and principles, for example, cross section or excitation function, apply

broadly to nuclear reactions, regardless of the type of reactor or accelerator

used.

2.1.1 Nuclear Reactions

A process involving interaction with a particular nucleus leading to the

alteration of its original state is known, in general terms, as a nuclear reaction.

A set consisting of a projectile and a target nucleus and their energy char-

acteristics is called the entrance channel of a given nuclear reaction. The exit

channel is the name given to the set of products of a nuclear reaction that are

characterized by their respective energy or internal excitation status. If a cer-

tain channel is not physically possible (e.g., if not enough energy is available),

it is said to be closed. Otherwise, it is open.

The total relativistic energy, momentum, angular momentum, total charge,

and number of nucleons are conserved in a nuclear reaction.Parity is also con-

served, as interactions in a nuclear reaction are defined by the strong nuclear

interaction, which conserves this nuclear state wave-function property.

One important characteristic of a nuclear reaction is the difference between

the kinetic energy of the initial participants and final products of the reaction

in the laboratory referential system (in which the target nucleus is considered

at rest). This difference is the Q value of the nuclear reaction. Representing the

kinetic energy in the laboratory reference system as K

lab

and the rest mass as

m, in a generic nuclear reaction it can be stated that

Q = K

lab

B

+K

lab

b

−K

lab

a

=[(m

a

+m

A

) −(m

B

+m

b

)]c

2

. (2.1)

Second equality results from relativist energy conservation and demon-

strates that Q is a characteristic of the reaction, regardless of the coordinate

system used.

A nuclear reaction can be exothermic or endothermic depending on the pos-

itive or negative value of Q. In an endothermic reaction, |Q| represents the

minimum energy given to the initial reagents in the center-of-mass system to

enable the nuclear reaction to take place.

In a real experiment setup, direct measurement of K

lab

B

is not always simple,

and momentum conservation is often used in a nonrelativistic approach to

deduce an expression that enables Q to be calculated from K

lab

a

and K

lab

b

only:

Q = K

lab

b

1 +

m

b

m

B

−K

lab

a

1 −

m

a

m

B

−

2

m

B

K

lab

a

K

lab

b

m

a

m

b

cos θ

lab

(2.2)

12 Nuclear Medicine Physics

From this expression, an important intrinsic characteristic of endothermic

nuclear reactions can be inferred: For each b product emission angle θ

lab

, mea-

sured in the laboratory reference system in relation to the projectile incidence

direction, a minimum projectile kinetic energy K

lab

a

is required to allow the

nuclear reaction to take place. This kinetic energy reaches its minimum value,

called threshold energy (E

T

), when θ

lab

= 0

o

.

In the laboratory reference system with A at rest, a projectile speed (v

lab

a

)

corresponding to a kinetic energy of |Q| is not enough to induce a nuclear

reaction. In fact, not all the projectile’s kinetic energy will be available for the

nuclear reaction, due to conservation of the center-of-mass momentum:

E

r

=|Q|

m

A

+m

a

m

A

⇒ (v

lab

a

)

min

=

2|Q|(m

A

+m

a

)

m

A

m

a

(2.3)

Two main mechanisms can be observed in typical nuclear reactions induced

by protons or deuterons in a cyclotron: direct reactions and compound nucleus

mechanisms.

A nuclear reaction is called direct (or sometimes, peripheral) when it

involves interaction leading to energy and/or particle transfer between the

projectile and the outer (peripheral) nucleons of the target nuclei, without

interference to other nucleons. Figures 2.1 and 2.2 illustrate some reaction

types that can be considered direct.

Adirectreactioninvolves only a small number of system degreesof freedom

and is characterized by a significant overlap of the initial and final wave

functions. Therefore, the transition from the initial to the final state takes

FIGURE 2.1

Diagram of examples of direct reactions, involving only energy transfer (elastic dispersion):

excitation of a single nucleon (left) and collective excitation of a rotational or vibrational state

(right).

Cyclotron and Radionuclide Production 13

Stripping

Knock-out

Pick-up

Direct exchange

Before After

FIGURE 2.2

Diagram of some types of direct reactions involving the exchange of nucleons.

place in a very short time (about 10

−22

s, the order of magnitude of the transit

time of a nucleon through a nucleus) and with minimum rearrange processes.

Consequently, a strong interdependence between the pre- and postreaction

energy states of the projectile, emitted particles and target nucleus can be

observed.This interdependencecauses(and is seenin) theanisotropicangular

distribution of the emitted particles, resulting from a strong correlation with

the projectile incident direction.

In a compound nucleus reaction mechanism, the projectile is captured in

the target-nucleus potential; and a highly excited system, the compound

nucleus, is formed. Projectile energy is distributed throughout all the com-

pound nucleus nucleons, reaching a state comparable to thermal equilibrium.

Even though the average energy per nucleon is insufficient to overcome the

binding potential, since the system particle number is relatively small, impor-

tant fluctuations in energy distribution will occur, until one or more nucleons

14 Nuclear Medicine Physics

gathers enough energy to exit the nucleus. The typical time interval between

projectile target penetration and particle emission is in the order of 10

−16

s.

It may be possible that, in a compound nucleus reaction, no particle is

emitted and all the excess energy is released through γ radiation emission.

This is the case in capture reactions, a mechanism predominant in thermal

neutron irradiation (and used in nuclear reactor radionuclide production),

but it is relatively infrequent in charged particle irradiation.

The process of forming the compound nucleus and the energy states that

are assumed characterize and define the specific properties of this type of

nuclear reaction.

Since the compound nucleus is essentially a nuclear excited state in which

energy is distributed through many particles, it can assume many different

states, called many-particle states. These excited states result from possible

energy distributions among the different nucleons (which should not be

confused with individual nucleon energy states) and are quantified states

defined by quantic numbers and properties, such as spin or parity. However,

their energy state value is associated with an intrinsic uncertainty resulting

fromHeisenberg’sprinciple, corresponding to approximatelyan electron-volt

(calculated on the basis of an energy state lifetime in the order of 10

−16

s).

If the energy available from the nuclear reaction equals one of the many

particles’ energy states in the compound nucleus to be formed, a resonance

phenomenon will occur and there will be maximum probability of compound

nucleus formation. Compound nucleus resonances are characteristic of this type

of nuclear reaction. However, these resonances are easy to observe only when

the projectile is a relatively low-energy nucleon, because in many particles,

the separation of energy states rapidly decreases as energy increases, and

energy width increases at the same rate.

An important specific property of compound nucleus reactions is the veri-

fication of the independence hypothesis, according to which the formation and

decay of the compound nucleus are independent processes [1]. As a con-

sequence, the relative probabilities of possible decay mechanisms will be

independent of each other and independent of the process leading to com-

pound nucleus formation. Therefore, the emission angular distribution is

expected to be isotropic.

Although the clear and total separation of direct and compound nucleus

reactions may be pedagogically convenient, these mechanisms are not

mutually exclusive over the whole projectile energy range for a given reaction.

Usually, even for the same projectile energy value, mechanisms of both

types and intermediate processes can be observed, even when, as in most

cases, one of the mechanisms is predominant. The relative importance of the

different mechanisms to a given nuclear reaction depends on projectile energy

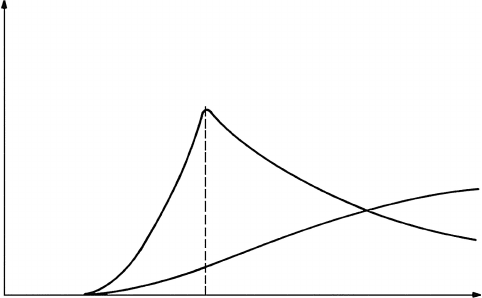

and on the Q value, as can be observed in Figure 2.3. In this example, the

upwardtrend (corresponding to a compound nucleus mechanism) is inverted

when the (p,n) channel is opened, as this channel statistically competes with

the (p,p

) channel for compound nucleus decay. The corresponding effect

Cyclotron and Radionuclide Production 15

Opening of the (p, n) channel

E

threshold

Proton beam energy

Relative contribution the different

mechanisms to the (p, p′) reaction

Compound nucleus

Direct

–Q (p, n)

FIGURE 2.3

Relative contribution of direct and compund nucleus mechanisms to a (p, p

) reaction, as a

function of projectile energy.

is particularly important, as, for emitted neutrons, the Coulomb barrier is

transparent.

Experimental evidence of combined mechanisms can be seen in the degree

of spatial anisotropy (even if sometimes very slight) that can always be found

in the nuclear reaction emission. This anisotropy is present even in reactions

characterized by compound nucleus formation, as a result of the interdepen-

dence between the entrance and exit channels due to the laws of conservation,

as the initial constants are determined by the entrance channel.

2.1.2 Cross Section

The cross section quantifies the probability, per projectile current-density

unit, of the occurrence of a given nuclear reaction. It is defined from the

number N

NR

of nuclear reactions induced when a beam of N

p

particles of a

given energy hits a surface with an N

target

target nucleus per unit area. The

incident beam is assumed to be parallel, monoenergetic, and composed of

small-sized particles (compared with the target nucleus). It is also assumed

that the nuclear reaction is induced only in a small proportion of the total

number of targets, which can, therefore, be considered constant. In these

conditions, the cross section σ for the production of a nuclear reaction is

given by

N

NR

= N

p

N

target

σ. (2.4)

Cross-section dimensions are area dimensions and measure occurrence

probability. This apparent ambiguity is explained by its physical significance,

16 Nuclear Medicine Physics

which can be understood by considering a simple classic collision problem

between a point particle and a target particle with a given radius. Classically,

every time the impact parameter is such that the incident particle hits the

target particle, a collision will occur. However, the collision of a certain pro-

jectile, with a given energy against a specific target, does not always lead to

the (expected) nuclear reaction. First, this is because it is a nondeterministic

quantic phenomenon, for which a strict definition of radius is not logical and

in which the nuclear force can be felt at a finite distance beyond it. Moreover,

even if the collision is 100% probable for a certain impact parameter, as in

classical mechanics, it should be noted that a nuclear reaction entrance chan-

nel can produce different exit channels. The physical phenomenon inherent

to these concepts can be interpreted as a proportional diminution of the tar-

get particle area in a classic collision. The cross section then represents the

effective area for the nuclear reaction to which it refers. However, it is not a

property of the target alone; but it is a compound property of both target and

projectile, reflected in the interaction between them.

In nuclear physics, it is convenient to use barn, b, as the cross-section unit.

It is related to the standard area unit (square meter) as follows:

1 barn = 10

−28

m

2

. (2.5)

2.1.3 Excitation Function

In any given nuclear reaction, each energy value for a projectile particle

beam hitting a target has a corresponding cross-section value. The set of

cross-section values in relation to particle beam energy is called the excitation

function of the given nuclear reaction.

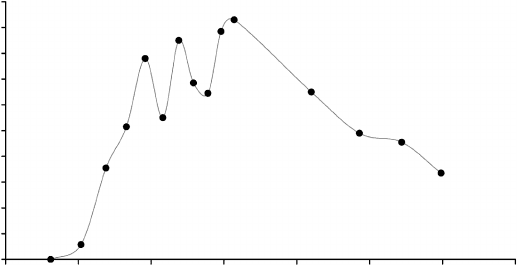

As an example, Figure 2.4 shows the excitation function of the

10

B(p,n)

10

C

reaction, obtained from cross-section values experimentally measured for

several energies [2].

2.1.4 Excitation Function and Radionuclide Production

In a study aimed at establishing a production processfor a given radionuclide,

two key steps can be identified in which knowledge of excitation functions

is vital: the choice of nuclear reaction to be used and the target incoming and

outgoing projectile beam energy values for a given reaction.

Since several different nuclear reactions can lead to production of the same

nuclide, knowledge of their excitation functions will determine which reac-

tionhasthe betteryield. Inpractice,experimental conditionslimit the choiceto

the reactions induced by the projectiles available and the acceleration energy

range. The respective excitation function is, therefore, an important selection

criterion for the available reactions, initially, to prevent the choice of any reac-

tion with a zero excitation function over the range of energies for which the

Cyclotron and Radionuclide Production 17

0

0

2

4

6

8

Cross section (mbarn)

10

12

14

16

18

20

5 10 15

Energy (Mev)

20 25 30 35

FIGURE 2.4

Excitation function for the

10

B(p, n)

10

C reaction. The line shown is an interpolation from the

experiment values, shown as black dots.

projectile beam can be accelerated and, second, to rank reactions in terms of

their efficiency in producing the desired nuclide.

However, the process of establishing a protocol for a given radionuclide

production is not confined to the choice of the nuclear reaction that leads to

a greater physical production yield. A key aspect to consider is the physical

and chemical characteristics of the constituent material of the target, which

determine the physical feasibility of implementation and its physical and

chemical stability during and between irradiation. These include mechanical

properties; heat capacity and thermal conductivity; the melting, evaporation,

and sublimation points; and chemical reactivity under the conditions con-

templated. These features also influence the produced isotope extraction or

separation process, in which the practicality, efficiency, and timing of the

process are decisive factors. Moreover, in terms of the raw material of the tar-

get, it is inevitable that the relationship between commercial availability and

price must be considered, which are, to a large extent, dependent on natural

occurrence.

The process of choosing the nuclear reaction for the production of a given

radionuclide involves, in most cases, a compromise between the excitation

functions of the possible reactions and their implementability. In practical

terms, the physical and chemical characteristics and the price or commercial

availability of the target material often become the predominant factors. One

example of this [3] is the preference for the proton irradiation of a pure water

(H

2

O) target, using the

16

O(p,α)

13

N reaction, in the production of nitrogen-13

(

13

N) in PET-dedicated cyclotrons. The cross-section values of this reaction

for the typical range of energies (up to a maximum value in the order of two

dozen MeV for protons) in this type of cyclotron are about half of those for