Langbein Hermann. People in Auschwitz

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

a type of synthetic rubber known as buna. They took an interest in Ausch-

witz because the camp could provide cheap inmate labor. Eventually, inmate

labor constructed the Buna Works at Monowitz, a short distance from the

main camp. Other German industries followed, employing Auschwitz inmate

labor in various subcamps. In March 1941, Reich Leader ss Heinrich Himmler

ordered the construction of a large camp for 100,000 Soviet POWs at Birke-

nau, in close proximity to the main camp. Most of the Soviet prisoners were

dead by the time Birkenau was reclassified as a concentration camp in March

1942.

With the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, the Nazi regime

moved to implement the so-called final solution, the murder of the European

Jews and Gypsies. At first, ss killing squads shot their victims in mass execu-

tions, but soon the killings were moved to newly built extermination camps,

where the victims were gassed with carbon monoxide.

Assembly-line mass murder in gas chambers started with the systematic

execution of persons with disabilities under a program euphemistically called

euthanasia. Starting in the winter of 1939–40, six killing centers on German

soil, each with a gas chamber and a crematorium, put to death about 80,000

disabled patients in less than two years. Thereafter the killing of the disabled

ran parallel to the murderof Jews and Gypsies. Since the overcrowded concen-

tration camps did not yet have the means for rapidly killing large numbers of

people, the facilities of theeuthanasia programwere utilized.Commissionsof

euthanasia and ss physicians selected inmates for shipment to the euthanasia

centers. In July 1941, victims began to be selected in Auschwitz.

Sometime in the summer of 1941, Himmler informed Höß, the Auschwitz

commandant, that he had chosen his camp as one of the sites where the final

solution would be implemented. Although the ss in Auschwitz would even-

tually copy the euthanasia method of mass killing—with gas chambers, cre-

matoria, and the stripping of gold teeth from corpses—it used hydrogen cya-

nide, known by the trade name Zyklon B, rather than carbon monoxide. As an

experiment, the ss tried out Zyklon B, otherwise used as a pesticide in con-

centration camps, to kill Soviet POWs in August 1941.

In February 1942, the first transports of Jews arrived in Auschwitz; the vic-

tims were gassed in the Old Crematorium at the main camp. In March 1942,

the killing operation was moved to Birkenau, utilizing two farm buildings for

this purpose. During the period March–June 1943, the construction there of

four large structures, each housing a gas chamber and a crematorium, was

completed. Soon, massive gassings commenced, claiming altogether about

1.1 million victims.

In November 1943, the expansion of the killing operation, of industrial ac-

tivities, and of the inmate population at Auschwitz led to a reorganization of

x n Foreword

the camp structure, resulting in three camps, each with its own commandant:

the main camp (Auschwitz I), Birkenau (Auschwitz II), and Monowitz (Ausch-

witz III). Auschwitz I did, however, retain some overall control.The comman-

dant of the main camp served as post senior, and various central offices, espe-

cially the Political Department and the post physician’s administration, were

still located in the main camp.

The most intense period of killings at Auschwitz began in 1944 with the

murder of Hungarian Jews, whose transports started to arrive in May. Jews

continued to be brought from other European countries and were also de-

stroyed en masse, as were the Jews from the so-called Theresienstadt family

camp, established in Birkenau in September 1943, and the Gypsies held in the

Birkenau Gypsy camp since February 1943.

In the fall of 1944, as the Red Army moved closer to Upper Silesia, the ss

prepared for a possible withdrawal. Rumors soon spread that they would kill

all inmates who knew too much, and first on the list were the Jewish inmates

who had been forced to work in the Sonderkommando of the crematoria. On

October 7, 1944,theSonderkommandostagedan unsuccessfuluprising, dam-

aging one of the crematoria. The gassings continued but at a reduced rate.

Finally, as the front drew closer to Auschwitz, Himmler ordered a halt to the

gassings, and in November 1944 the ss destroyed the crematoria. On Janu-

ary 17, 1945, the ss conducted the last roll call in Auschwitz. A day later, the

camp was evacuated, and its inmates started on the death marches and death

transports toward the interior of Germany. Only very sick inmates were left

behind. On January 27, 1945, Soviet troops liberated theAuschwitzcamp com-

plex.

The final defeat of Germany revealed for the first time the extent of the

Naziregime’smassivecrimes.Pictures of theliberated campsand their surviv-

ing inmates appeared in the newspapers and cinema newsreels of the nations

that had defeated Germany. But because the extermination camps had been

located in the East and liberated by the Soviets, the pictures seen in the West

were primarily of the camps whose inmates were liberated by the Western

Allies.The best-known images came from Bergen-Belsen, liberated by British

troops. The landscape of death there was shocking, but Bergen-Belsen had

not been a killing center.

In the early postwar years, the public in the West did not distinguish be-

tween the extermination camps in the East and the concentration camps in

the West. Usually, the term ‘‘death camp’’ was applied to both, a usage that

has persisted.This began to change only in the 1970s, as greater public inter-

est focused on the Holocaust and the extermination camps. But camps like

Treblinka had disappeared, totally destroyed by the Germans. This was not

true of Auschwitz, which had been far too large to eradicate. True, Monowitz

Foreword n xi

and the subcamps had disappeared; only the factories constructed by the Ger-

mans survived. The main camp, however, remained almost intact and drew

growing numbers of visitors. At Birkenau, which was difficult to maintain and

preserve, the barracks were mostly gone; rapidly growing weeds covered virtu-

ally everything. Even so, today, the barbed wire is still there, as are the railroad

tracks that led to the siding where the ss selected from the arriving transports

those destined for the gas chambers. Despite the disappearance of the bar-

racks, their chimneys stand here and there, creating an eerie landscape for the

visitor viewing the camp from the lookout at the front gate.

Although we now have considerable information about Auschwitz and Bir-

kenau, it comes mainly from archival sources and trial records. In the English-

speaking world, the principal sources for Auschwitz are the memoirs of sur-

vivors. Most were written by lower-level inmates, whose perspective stemmed

from their own experiences and the events in their immediate surroundings.

The best of the Jewish memoirs undoubtedly is Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man,

and the best Polish memoir probably is Wieslaw Kielar’s Anus Mundi.

Hermann Langbein’s People in Auschwitz is a very different kind of memoir.

Langbein occupiedacrucial positionasclerk tothesspostphysicianat Ausch-

witz; as an inmate functionary, he could see and know things not visible to

the common inmate. And, as a member of the Auschwitz resistance, he had

access to information not available to others. Langbein’s account, which deals

with the ss as well as the inmates, intertwines his own experiences with quo-

tations from other inmates, derived from official sources as well as personal

interviews, and from ss personnel, drawn from statements made in detention

and at trial. Written in an objective, sober style, Langbein’s book presents us

with a narrative few others could have provided.

Hermann Langbein was born in Vienna in 1912 into an Austrian middle-

class family; his father was a white-collaremployee. His mother was Catholic;

his father was Jewish but converted to Protestantism when he married. Lang-

bein’s mother died in 1924 and his father ten years later. Hermann attended

a Vienna Gymnasium, an essential stepping stone for university attendance,

receiving his diploma in 1931. He wanted to become an actor and therefore

did not follow his older brother, Otto, into the university. Instead, he started

his training at the Deutsche Volkstheater.

At this time, Langbein’s general political outlook was leftist, but he did not

yet have any party ties. He was definitely opposed to the German Nazis and

the Austro-Fascists. He did a great deal of reading during this period, mostly

works by progressive authors; in a later interview, he mentioned Upton Sin-

clair. His brother Otto, who influenced him greatly, joined the Communist

Party in 1932, and Hermann followed him in January 1933. Langbein’s term

at the Volkstheater ended in 1933, and he subsequently appeared in a number

xii n Foreword

of plays in various theaters. Arrested in 1935, he was jailed until 1937 by the

Austrian fascist regime. After theAnschluss in 1938, Langbeinfled to Switzer-

land with his girlfriend Gretl, also a member of the party. They made their

way to Paris, where they met Otto and various communist friends. Langbein

soon crossed into Spain to join the fight against Franco as a member of the

International Brigade, while Otto, who was ill, and Gretl stayed in Paris.

By the time Langbein entered Spain, the war had already been lost by the

republican side. Still, he was involved in bitter battles. Of course, everyone

was looking toward the future, as Langbein’s letters to Paris show. Gretl de-

cided to emigrate to Australia; Langbein was less enthusiastic about going so

far from Europe. Nevertheless, he studied English, thought about a future as

an actor in Sydney, and even talked about marriage. Late in 1938, Gretl left for

Australia while Langbein was still in Spain; world history separated them.

In April 1939, Langbein finally was permitted to cross the French border,

only to find himself interned, as were most of the other members of the Inter-

national Brigade. He was first in Saint-Cyprien, then in Gurs, and finally in

Le Vernet. After the defeat of France, the Vichy regime handed the members

of the International Brigade over to the Germans, and thus Langbein entered

the world of the German concentration camps.The first one was Dachau. Fol-

lowing several weeks at hard labor, Langbein was assigned to the inmate in-

firmary, since he knew both shorthand and Latin. There he served as clerk for

several ss physicians, including Dr. Eduard Wirths. In August 1942, Langbein

was transferred to Auschwitz.

Being from Austria, which had been absorbed into theReich, Langbein was

classified in the concentration camp as a German, the most privileged type

of prisoner. That privileged status was enhanced in Auschwitz because there

the percentage of German inmates was even smaller than in camps such as

Dachau and Buchenwald. Under the German racial laws, however, he should

have been classified as a Jew. When he was registered in Dachau and asked

about his lineage, he prevaricated, telling the clerk that his father was partly

Jewish, a so-called Mischling, but that he did not know exactly to what degree,

except that it would not usually classify him as a Jew. Surprisingly, no one ever

followed up, and therefore he was also registered in Auschwitz as not being

Jewish.

Langbein was transferred to Auschwitz because of the need there for extra

personnel to assist in the battle against epidemics; he was assigned to the in-

mate infirmary in the main camp as a nurse. Within a short time, Dr. Wirths

was transferred to Auschwitz as the post physician. He recognized Langbein

and picked him as his clerk. As this book illustrates, in that position Langbein

not only was privy to much confidential information, including the statistics

of inmates killed and transports gassed, but also was able to influence Wirths

Foreword n xiii

to improve conditions for his fellow inmates. That privileged vantage point,

plus his activities as a member of the resistance cell in the camp, gave him a

feel for how Auschwitz functioned, a sense that few others could match.

In August 1944, Langbein was transferred to the Neuengamme concen-

tration camp near Hamburg and then to various subcamps of Neuengamme.

Duringthe period of death marches and death transports,he fled froma trans-

port. Shortly thereafter, provided with a pass by the U.S. Army, he returned to

Vienna by bicycle.

Langbein proceeded to work for the Austrian Communist Party, organiz-

ing and directing party schools in various Austrian provinces. At this time, he

met his future wife, Loisi, a journalist and party member; they were married

in 1950 and had two children, Lisa and Kurt.

Slowly, Langbein became dissatisfied with lifewithin the Communist Party

and began to stray from the strict party line—reading, for example, Heming-

way’s novel about the Spanish civil war, For Whom the Bell Tolls, even though it

lacked the party’s stamp of approval. He always had been someone who spoke

his mind; he did not easily compromise his convictions. Caught up in intra-

party conflicts, he eventually became their victim. He was removed from his

position in party education and was forced in 1953 to move to Budapest to

take charge of the Austrian program on Hungarian radio. His disaffection in-

creased as he saw the shocking reality of life in a Stalinist people’s democracy.

After about a year, he returned to Vienna to join the staff of one of the party

papers.There he began to suffer under censorship that he found to be absurd.

When the newspaper closed in 1955, Langbein earned his living as secretary

of the International Auschwitz Committee and of the Austrian Concentration

Camp Association, both dominated by communists.

Two events in 1956 led to Langbein’s break with the Communist Party: the

suppression of the Hungarian uprising and Nikita Khrushchev’s speech to

the Twentieth Party Congress in the Soviet Union. More and more, Langbein

acted on his convictions even if they clashed with the party line. In 1957, his

brother Otto left the party, but Hermann refused to drop out quietly.The most

public of his activities was the organization of a telegram protesting the trial

and conviction of Imre Nagy. As he likely knew it would, this led to his pub-

lic expulsion from the party in 1958. Although the International Auschwitz

Committee and the Austrian Concentration Camp Association were not com-

munist bodies, he was soon pushed out of them and lost his entire income.

After 1958, Langbein turned to writing to make a living. Through connec-

tions, he received a contract from the publisher EuropaVerlag and wrote a few

books on politics. But his greatest interest lay in the Nazi past. After all, his

opposition to Nazism and fascism had originally led him into the Communist

xiv n Foreword

Party. In the Auschwitz resistance, he had worked with both communists and

noncommunists. Following the war, he wanted to talk about the experiences

of the camps and was angered when he found that none of the party leaders

cared to find out what had happened in Auschwitz. In 1947–48, he wrote an

account of his experiences but had difficulty publishing it.The book appeared

under the title Die Stärkeren: Ein Bericht (The stronger: A report) in 1949.

While still secretary of the International Auschwitz Committee, Langbein

had become involved in the effort to bring the Auschwitz criminals to jus-

tice. The first case in which he participated concerned the obstetrician and

gynecologist Carl Clauberg, who had conducted sterilization experiments on

Jewish female inmates at Auschwitz. Sentenced by the Soviets to hard labor,

he was released to West Germany through a deal made by Konrad Adenauer.

In the name of the International Auschwitz Committee, Langbein filed an

accusation against Clauberg, who was arrested and died in jail awaiting trial.

He later filed an accusation against Josef Mengele, providing the names of

witnesses for the West German prosecutors, but Mengele disappeared from

Argentina before he could be extradited. Even after he had lost his position

with the camp committees, Langbein continued to provide help in the prose-

cution of war criminals, lateras secretary of the noncommunist Comité Inter-

national des Camps.

In 1958, Langbein filed an accusation against Wilhelm Boger, a former

member of the Political Department at Auschwitz. This eventually led to the

first big Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt, which opened on December 20, 1963,

and ended on August 20, 1965. Langbein attended most of the court’s ses-

sions and, shortly after the verdict was announced, published a two-volume

documentary account of the trial.

Langbein used the next four to five years to write a clear-eyed study of

Auschwitz, drawing on his own experiences, as well as testimony at trials,

and the accounts of fellow inmates.The book was published by Europa Verlag

in 1972 as Menschen in Auschwitz (People in Auschwitz). As he told the Aus-

trian political scientist Anton Pelinka, the use of the word Menschen, that is,

‘‘human beings,’’ was meant to show that he tried his best to be objective, not

to demonize even the ss. He did this in contrast to Benedict Kautsky, who in

1946 used thetitle Teufel und Verdammte (Devils and thedamned) forhis memoir

of life in the concentration camps.

Until his death in Vienna in 1995, Langbein continued to write, participate

in conferences, serve as secretary of the Comité, and speak to school classes

as a witness. Wherever he appeared, he never indulged in self-dramatization.

He would point out that his own condition as a political prisoner, who arrived

in Auschwitz without kin, differed substantially from that of Jewish prisoners

Foreword n xv

who arrived there with their families and soon realized that those dearest to

them had been killed. Hewas always sure to discuss in his presentations about

racial mass murder the fate not only of Jews but also of Gypsies.

I first met Hermann Langbein in 1987 at a conference in Hamburg. Later

I also met him at a conference in Cologne and a few more times in Vienna.

He always treated me like a comrade, insisting that we use first names and

informal address. His attitude was probably due to the fact that he consid-

ered me a fellow Auschwitz survivor, although my three months in Birkenau

could hardly match his experience. Still, I do remember enough to attest to

the accuracy with which Langbein’s book delineates the texture of life and of

death there. As a fellow historian, I also can attest to the accuracy of his in-

terpretation, which I share. I do not believe that one can explain Auschwitz as

a horrible chapter in Jewish history alone; an explanation also must take into

full account Gypsies and other victims. In the larger context, Auschwitz epito-

mized a total negation of the values of Western civilization. Langbein’s skilled

mixture of personal observations and historical knowledge makes his book

unique among Holocaust memoirs. I am thereforevery happy that an English-

language translation of Menschen in Auschwitz finally is being published. All

those, especially students, interested in the dark planet that was Auschwitz

will profit from reading People in Auschwitz.

xvi n Foreword

Introduction

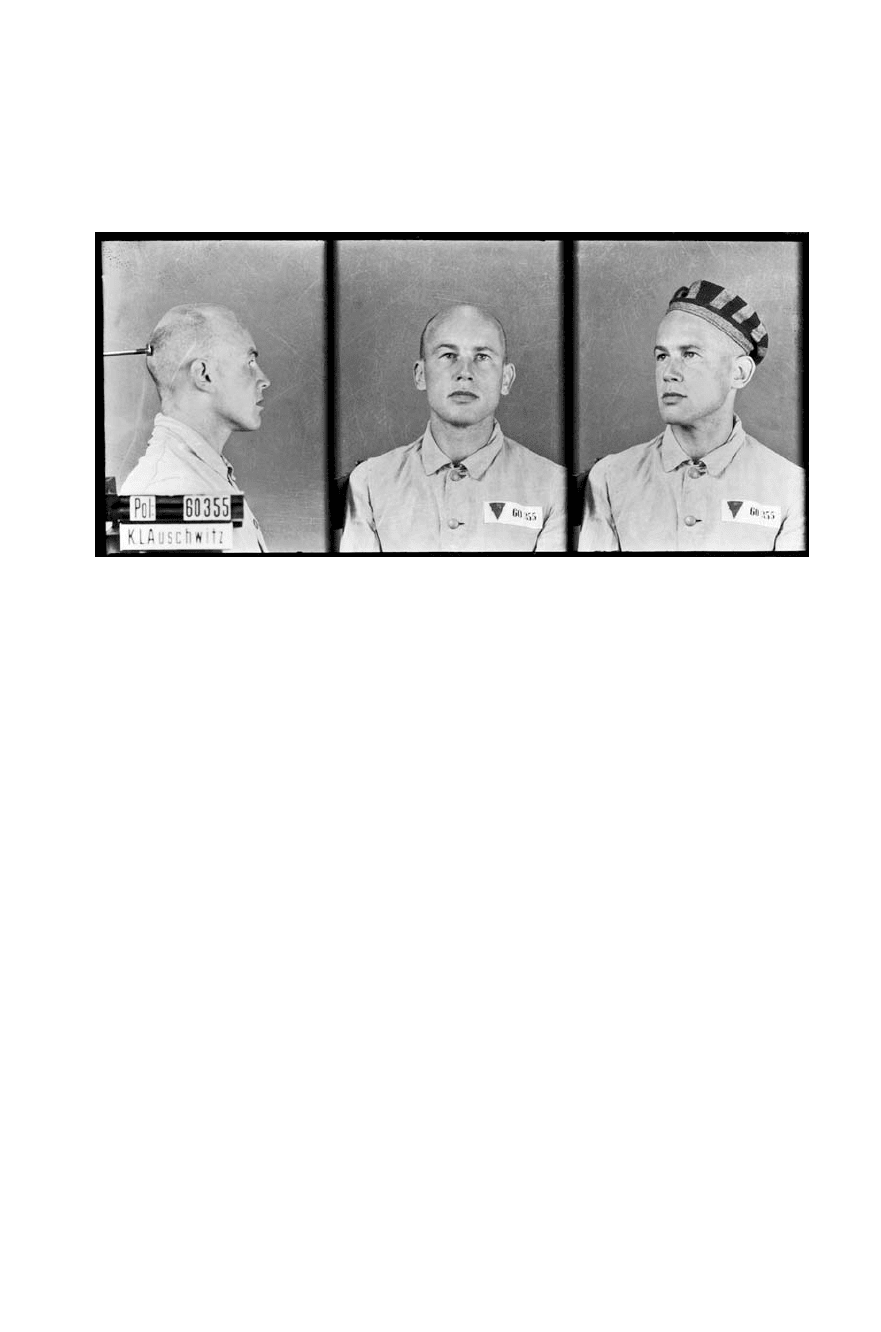

Auschwitz prisoner Hermann Langbein, ca. 1940. Photograph from United States Holocaust

Memorial Museum, courtesy of Panstwowe Muzeum w Oswiecim-Brzezinka.

author’s rationale

nnn

‘‘What Auschwitz was is known only to its inmates and to no one else.’’ This

is what Martin Walser wrote under the impression of the Auschwitz trial in

Frankfurt. ‘‘Because we cannot empathize with the situation of the prisoners,

because their suffering exceeded any previous measure and we therefore can-

not form a human impression of the immediate perpetrators, we call Ausch-

witz a hell and the evildoers devils. This might be an explanation for the fact

that when we talk about Auschwitz, we use words that point the way beyond

our world.’’ Walser concludes his observation tersely: ‘‘However, Auschwitz

was not hell but a German concentration camp.’’

Auschwitz was created in the middle of the twentieth century by the ma-

chinery of a state with old cultural traditions. It was real.

In that camp people were exposed to extreme conditions. This study will

describe how both prisoners and guards reacted to them, for the people who

lived in Auschwitz on the other side of the barbed wire had also been placed in

an extreme situation, though it was quite different from the one forced upon

the prisoners.

‘‘No one can imagine exactly what happened....Allthiscanbeconveyed

onlybyoneofus,...someonefromoursmallgroup, our inner circle, pro-

vided that someone accidentally survives.’’ These words were written by Zel-

man Lewental, a Polish Jew who was forced to work in the gas chambers of

Auschwitz. He was tormented by the idea that posterity would never know

what he had to experience. Since he had no hope of surviving Auschwitz, he

buried his notes near one of the crematoriums. They were dug up in 1961, but

only scraps could still be deciphered.

n Many prisoners were plagued by the sameworry as Lewental: that theworld

would never learn about the crimes committed in Auschwitz, or that if any

of these became known, they would not be believed. This is how improbable

a description of those events was bound to seem to outsiders. I still remem-

ber some conversations about this subject. The friends who voiced such fears

perished in Auschwitz, but I survived and have borne the burden of a respon-

sibility.We regard it as our task to keep insisting that lessons must be learned

from Auschwitz.

For this reason many people have written down their experiences. Shortly

after his liberation Viktor Frankl wrote: ‘‘We must not simplify things by de-