Klir G.J. Uncertainity and Information. Foundations of Generalized Information Theory

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

under the following specifications:

(a) x = 65% and T = True;

(b) x = 65% and T = False;

(c) x = 50% and T = True;

(d) x = 50% and T = False;

(e) x = 76% and T = Fairly true;

(f) x = 76% and T = Very false.

312 7. FUZZY SET THEORY

Table 7.2. Matrix Representations of Fuzzy Relations Employed in Exercises 7.25–7.27

y

1

y

2

y

3

x

1

1.0 0.0 0.7

P

1

= x

2

0.3 0.2 0.0

x

3

0.0 0.5 1.0

y

1

y

2

y

3

y

4

x

1

1.0 0.9 0.8 0.7

x

2

0.6 1.0 0.5 0.4

P

2

=

x

3

0.3 0.2 1.0 0.1

x

4

0.2 0.3 0.4 1.0

y

1

y

2

y

3

y

4

y

5

x

1

0.9 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.9

x

2

0.7 0.8 0.9 0.7 0.6

P

3

=

x

3

0.6 0.5 0.8 0.6 0.5

x

4

0.3 0.4 0.7 0.3 0.4

x

5

0.2 0.5 0.6 0.5 0.2

x

6

0.1 0.3 0.5 0.3 0.1

z

1

z

2

z

3

z

4

y

1

1.0 0.0 0.7 0.5

Q

1

= y

2

0.0 1.0 0.0 1.0

y

3

0.7 0.0 1.0 0.8

z

1

z

2

z

3

z

4

z

5

z

6

y

1

0.0 0.8 0.6 0.0 0.4 0.2

Q

2

=

y

2

0.0 0.0 0.9 0.9 0.7 0.7

y

3

1.0 1.0 0.0 0.5 0.0 0.0

y

4

1.0 1.0 0.5 0.0 1.0 1.0

z

1

z

2

z

3

z

4

z

5

z

6

z

7

y

1

1.0 0.9 0.9 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2

y

2

1.0 0.9 1.0 0.8 0.7 0.7 0.5

Q

3

=

y

3

1.0 1.0 0.8 0.9 0.0 0.0 0.0

y

4

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.7 0.8 0.0 0.0

y

5

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.6 0.7 0.0

y

6

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.6

È

Î

Í

Í

È

Î

Í

Í

˘

˚

˙

˙

˘

˚

˙

˙

È

Î

Í

Í

Í

È

Î

Í

Í

Í

˘

˚

˙

˙

˙

˘

˚

˙

˙

˙

È

Î

Í

Í

Í

Í

Í

È

Î

Í

Í

Í

Í

Í

˘

˚

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

˘

˚

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

7.29. Repeat Exercise 7.28 for the property of medium humidity, which

is expressed by the trapezoidal-shaped fuzzy interval M =·20, 40, 60,

80Ò.

7.30. The probabilities, p(r), of daily receipts, r, of a shop (rounded to

the nearest hundred dollars) that have been obtained from statistical

data collected over many years are shown in Table 7.1b. Consider three

fuzzy events: low, medium, and high receipts and assume that they are

represented by trapezoidal-shaped fuzzy intervals L =·18, 18, 21, 23Ò,

M =·21, 23, 27, 29Ò, and H =·27, 29, 32, 32Ò, respectively. Determine the

degrees of truth of the following propositions:

(a) The daily receipts are low;

(b) The daily receipts are medium;

(c) The daily receipts are high.

7.31. Modify the granulation defined in Figure 7.10b by replacing the trian-

gular-shaped granules with:

(a) Trapezoidal-shaped granules, with small plateaus around the ideal

values;

(b) Granules of the shape illustrated by membership function C in

Figure 7.4 and defined in Exercise 7.4;

(c) Granules of the shape illustrated by membership function F in

Figure 7.4 and defined in Example 7.3.

7.32. Show that the defuzzified value d(A) obtained by the centroid defuzzi-

fication method may be interpreted as the expected value of x based on

A.

7.33. Show that the defuzzified value d(A) defined by Eq. (7.41) is the value

of x for which the area under the graph of membership function A is

divided into two equal areas.

7.34. Using the centroid defuzzification method defuzzify the following fuzzy

sets:

(a) Fuzzy number A(x) = max{0, 4x - 4 - (x - 2)

2

};

(b) Fuzzy interval L in Figure 7.7a;

(c) The two fuzzy numbers obtained in Example 7.5 and shown in

Figure 7.5;

(d) Fuzzy set A that is equal to the possibility profile r in Figure 6.1 (i.e.,

A(x) = r(x) for all x Œ ⺞

15

);

(e) Fuzzy interval A defined by the following a-cut representation:

a

aaa

aa a

A =

()

+-

[]

Œ

(

]

+-

[]

Œ

(

]

Ï

Ì

Ó

15 1754 05 0 05

254 05 051

..,. ,.

., . ., .

when

when

EXERCISES 313

7.35. Repeat Exercise 7.34 for some other defuzzification methods defined by

Eqs. (7.43) and (7.44). Choose at least one value of l < 1 and one value

of l > 1.

7.36. Every rectangle may be considered to some degree a member of a fuzzy

set of squares. Using common sense, define a possible membership func-

tion of such a fuzzy set.

314 7. FUZZY SET THEORY

8

FUZZIFICATION OF

UNCERTAINTY THEORIES

315

The limit of language is the limit of the world.

—Stephen A. Tyler

8.1. ASPECTS OF FUZZIFICATION

Perhaps the best description of the nature of fuzzification is contained in the

well-known classical paper by Goguen [1967]: “Fuzzification is a process of

imparting a fuzzy structure to a definition (concept), a theorem, or even a

whole theory.” The strength of this deceivingly simple description is its sweep-

ing generality. The single sentence captures the essence of a wide variety of

issues that must be addressed when mathematical concepts, properties, or the-

ories based on classical sets are generalized to their counterparts based on

fuzzy sets of some type.

One method of fuzzifying various properties (concepts, operations,

theorems) of classical set theory is to use the a-cut (or strong a-cut) repre-

sentations of fuzzy sets. Since a-cuts (as well as strong a-cuts) are classical sets,

every property of classical set theory applies to them. A property of classical

sets is fuzzified (that is, it becomes a property of fuzzy sets) via the a-cut rep-

resentation by requiring that it holds (in the classical sense) in all a-cuts of

the fuzzy sets involved. Any property of fuzzy sets of some specific type that

is derived from a property of classical sets in this way is called a cutworthy

property.

For standard fuzzy sets, there are many properties that are cutworthy. One

such property is convexity of fuzzy sets. A fuzzy set is said to be convex if and

Uncertainty and Information: Foundations of Generalized Information Theory, by George J. Klir

© 2006 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

only if all its a-cuts are convex sets in the classical sense. An important class

of special convex fuzzy sets consists of fuzzy intervals. A fuzzy set on ⺢ is said

to be a fuzzy interval if and only if all its a-cuts are closed intervals of real

numbers (i.e., classical convex subsets of ⺢). Arithmetic operations on fuzzy

intervals are also cutworthy.At each a-cut, they follow the rules of either stan-

dard or constrained arithmetic on closed intervals of real numbers.

It is significant that the standard operations of intersection and union of

fuzzy sets (min and max operations) are cutworthy. As a consequence, other

operations that are based solely on them are cutworthy as well. They include,

for example, the max–min composition of binary fuzzy relations as well as the

relational join defined by the min operation. The concept of cylindric closure

of fuzzy relations is also cutworthy when the intersection of the cylindric

extensions of the given fuzzy relations is defined by the min operation.

Important examples of cutworthy properties are some properties of binary

fuzzy relations on X

2

, such as equivalence, compatibility, or partial ordering.

Classical equivalence relations, for example, are defined by three properties:

(i) reflexivity; (ii) symmetry; and (iii) transitivity. Let these properties be

defined for fuzzy relations, R, as follows:

(i) R is reflexive iff R(x, x) = 1 for all x ŒX.

(ii) R is symmetric iff R(x, y) = R(y, x) for all x,y ŒX.

(iii) R is transitive (or, more specifically, max–min transitive) iff

(8.1)

for all pairs ·x,zÒŒX

2

.

Then, any binary fuzzy relation on X

2

that possesses these properties is a fuzzy

equivalence relation in the cutworthy sense. That is, all a-cuts of any binary

fuzzy relation that possesses these properties are classical equivalence rela-

tions. This follows from the fact that each of the three properties is cutworthy.

In the case of reflexivity and symmetry, it is obvious. In the case of transitiv-

ity, it is cutworthy since it is defined in terms of the standard operations of

intersection and union, which are cutworthy.

EXAMPLE 8.1. Consider the binary fuzzy relation R on X

2

, where X =

{x

i

|i Œ ⺞

7

}, which is defined by the matrix

xxxxxxx

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

1234567

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

10

08

00

04

00

00

00

08

10

00

04

00

00

00

00

00

10

00

10

09

05

04

04

00

10

00

00

00

00

R =

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

000

10

00

10

09

05

00

00

09

00

09

10

05

00

00

05

00

05

05

10

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

È

Î

Í

Í

Í

Í

Í

Í

Í

Í

Í

˘

˚

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

Rxz Rx y Ryz

yY

,maxmin,,,

()

≥

()(){}

Œ

316 8. FUZZIFICATION OF UNCERTAINTY THEORIES

It is easy to see that this relation is reflexive and symmetric. It is also max–min

transitive, but that is more difficult to verify. One convenient way to verify it

is to calculate (R

°

R) » R where

°

denotes the max–min composition and »

denotes the standard union operation. Then, R is transitive if and only if

The given relation satisfies this equation. Hence, it is max–min transitive and,

due to its reflexivity and symmetry, it is a fuzzy equivalence relation. This can

be verified by examining all its a-cuts.

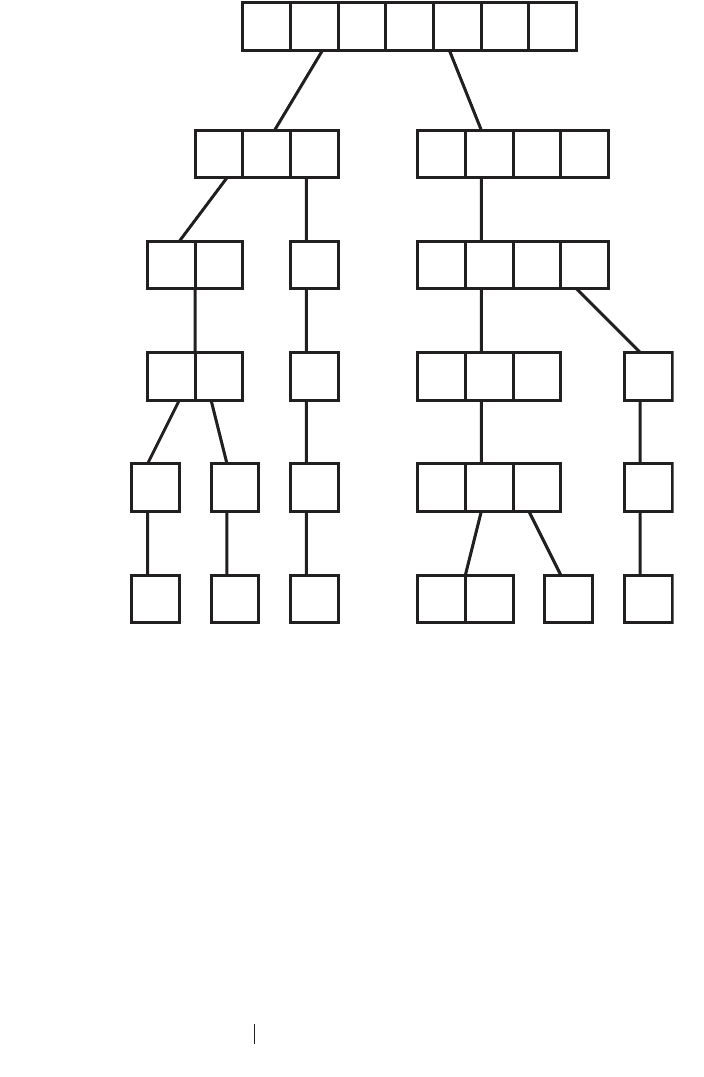

The level set of the given relation R is L

R

= {0, 0.4, 0.5, 0.8, 0.9, 1}. There-

fore, R represents six classical equivalence relations, one for each a ŒL

R

. Each

of these equivalence relations,

a

R, partitions the set X in some particular way,

a

p(X). Since

a ¢

R 債

a

R when a¢≥a, clearly

The six partitions of the given relation are shown in the form of a partition

tree in Figure 8.1. The partitions become increasingly more refined when

values of a in L

R

increase.

Other cutworthy types of binary fuzzy relations can be defined in a similar

way. Examples are fuzzy compatibility relations (reflexive and symmetric) and

fuzzy partial orderings (reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive). For fuzzy

partial orderings, the property of fuzzy antisymmetry is defined as follows: for

all x, y ΠX, if R(x, y) > 0 and R(y, x) > 0, then x = y. This, clearly, is a cut-

worthy property.

It is important to realize that there are many fuzzy-set generalizations of

properties of classical sets that are not cutworthy. A fuzzy-set generalization

of some classical property is required to reduce to its classical counterpart

when membership grades are restricted to 0 and 1, but it is not required to be

cutworthy.There often are multiple generalizations of a classical property, but

only one or, in some cases, none of them is cutworthy. Examples of fuzzy-set

generalizations that are not cutworthy are all operations of intersection and

union of fuzzy sets (t-norms and t-conorms) except the standard ones (min

and max). Even more interesting examples are operations of complementa-

tion of fuzzy sets, none of which is cutworthy, even though all of them are, by

definition, generalizations of the classical complementation.

Another way of connecting classical set theory and fuzzy set theory is to

fuzzify functions. Given a function

where X and Y are crisp sets, we say that the function is fuzzified when it is

extended to act on fuzzy sets defined on X and Y. That is, the fuzzified func-

tion maps, in general, fuzzy sets defined on X to fuzzy sets defined on Y.

Formally, the fuzzified function, F, has a form

fX Y:,Æ

¢

()

£

()

¢≥

aa

pp aaXXwhen .

RRR R=

()

»o .

8.1. ASPECTS OF FUZZIFICATION 317

where F(X ) and F(Y) denote the fuzzy power sets (sets of all fuzzy subsets)

of X and Y, respectively. To qualify as a fuzzified version of f, function F must

conform to f within the extended domain F(X) and F(Y). This is guaranteed

when a principle is employed that is called an extension principle. According

to this principle

is determined for any given fuzzy set A ŒF(X) and all y ŒY via the formula

(8.2)

By

Ax x X f x y

fy

()

=

()

Œ

()

=

{}

()

π∆

Ï

Ì

Ó

-

sup ,

.

0

1

when

otherwise

BFA=

()

FX Y:,FF

()

Æ

()

318 8. FUZZIFICATION OF UNCERTAINTY THEORIES

x

1

x

2

x

3

x

4

x

5

x

6

x

7

x

1

x

2

x

4

x

3

x

5

x

6

x

7

x

1

x

2

x

4

x

3

x

5

x

6

x

7

x

1

x

2

x

4

x

3

x

5

x

6

x

7

x

1

x

2

x

4

x

3

x

5

x

6

x

7

x

1

x

2

x

4

x

3

x

5

x

6

x

7

a

= 0.0

a

= 0.4

a

= 0.5

a

= 0.8

a

= 0.9

a

= 1.0

Figure 8.1. Partition tree of the fuzzy equivalence relation in Example 8.1.

The inverse function

of F is defined, according to the extension principle, for any given B ŒF(Y)

and all x ŒX, by the formula

(8.3)

where y = f(x). Clearly,

for all A ŒF(X ), where the equality is obtained when f is a one-to-one

function.

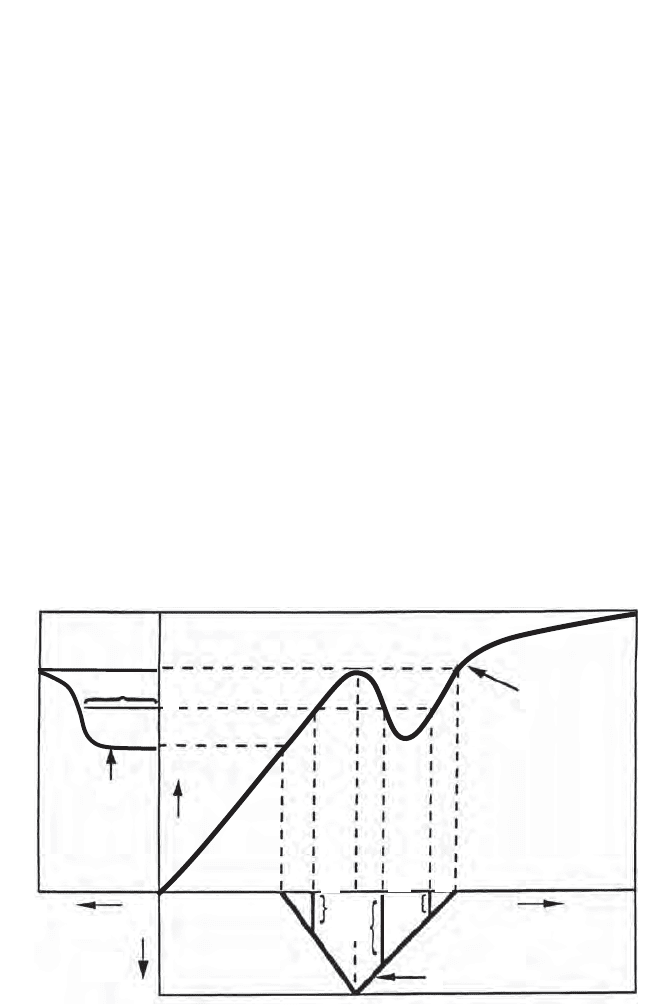

The use of the extension principle is illustrated in Figure 8.2, which shows

how fuzzy set A is mapped to fuzzy set B via function F that is consistent with

the given function f. That is, B = F(A). For example, since

we have

Bb Aa Aa Aa

()

=

() () (){}

max , ,

123

bfa fa fa=

()

=

()

=

()

123

,

FFA A

-

()

[]

1

FBx By

-

()

[]

()

=

()

1

,

FY X

-

()

Æ

()

1

: FF

8.1. ASPECTS OF FUZZIFICATION 319

x

B

(y)

a

2

a

1

a

3

A(a )

2

A(a )

3

B(b)

A(x)

B

A(a )

1

0

A

1

y

f

1

A(x)

b

Figure 8.2. Illustration of the extension principle for fuzzy sets.

by Eq. (8.2). Conversely,

by Eq. (8.3).

The introduced extension principle, by which functions are fuzzified, is basi-

cally described by Eqs. (8.2) and (8.3). These equations are direct generaliza-

tions of similar equations describing the extension principle of classical set

theory. In the latter, symbols A and B denote characteristic functions of crisp

sets.

To fuzzify a function of n variables of the form

the formula in Eq. (8.2) has to be replaced with the more general formula

(8.4)

Similarly, Eq. (8.3) has to be replaced with

(8.5)

Equation (8.4) can be further generalized by replacing the min operator with

a t-norm.

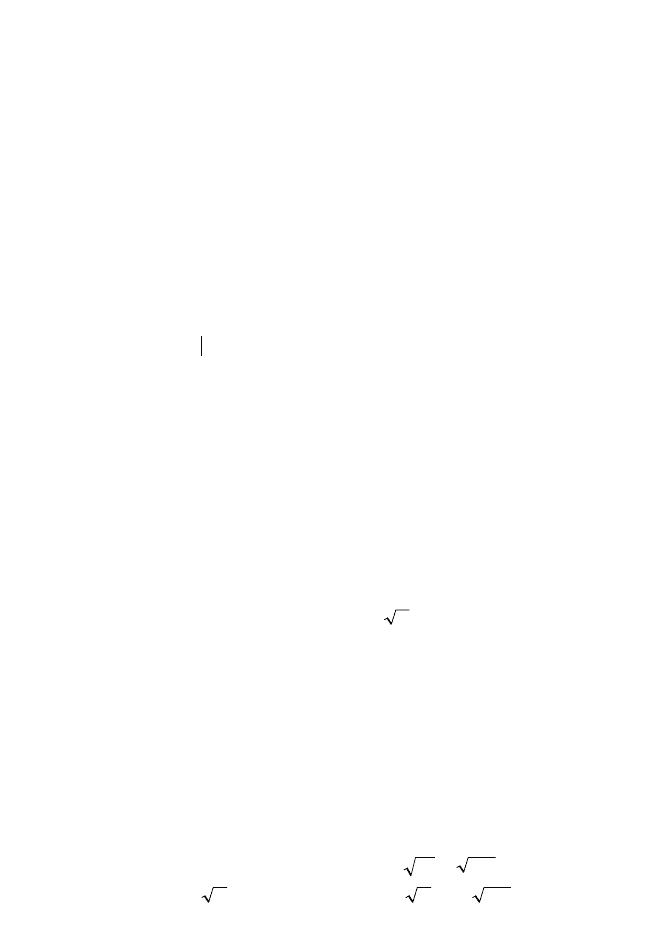

EXAMPLE 8.2. Consider the function y = , where x Π[0, 5], and the tri-

angular fuzzy number

which represents an approximate assessment of value x. Using the extension

principle, the value of y is approximately assessed by the fuzzy number

Fuzzification also can be attained via the mathematical theory of categories.

In this way, a fuzzy structure is imparted into various categories of mathe-

matical objects by fuzzifying morphisms through which the categories are

By x

xx

xx=

()

=

-Œ

[

)

-Œ

[]

Ï

Ì

Ô

Ó

Ô

21 051

32 115

0

when

when

otherwise.

.,

,.

Ax

xx

xx

()

=

-Œ

[

)

-Œ

[]

Ï

Ì

Ô

Ó

Ô

21 051

32 115

0

when

when

otherwise,

.,

,.

x

FBxx x By

n

-

()

[]

◊◊◊

()

=

()

1

12

,, , .

By

Ax x X i fx x x y f y

i

ii i i n n

n

()

=

()

ŒŒ

◊◊◊

()

=

{}()

π∆

Ï

Ì

Ó

Œ

-

sup min , , , , ,

⺞

⺞

12

1

0

when

otherwise.

fX X X Y

n

:

...

,

12

¥¥¥Æ

FBa FBa FBa Bb

-- -

()

[]

()

=

()

[]

()

=

()

[]

()

=

()

1

1

1

2

1

3

320 8. FUZZIFICATION OF UNCERTAINTY THEORIES

defined. This is a powerful approach to fuzzification, which has played an

important role in fuzzifying many areas of mathematics, such as topology,

analysis, various algebraic theories, graphs, hypergraphs, geometry, and finite-

state automata. Because the reader of this book is not expected to have suffi-

cient background in category theory, this approach to fuzzification is not

employed in this chapter.

There are usually multiple ways in which a given classical mathematical

structure can be fuzzified. These ways of fuzzification are distinguished from

one another by choosing which components of the structure are going to be

fuzzified and how. These choices have to be made in each given application

context on pragmatic grounds.

8.2. MEASURES OF FUZZINESS

The pragmatic value of fuzzy logic in the broad sense consists of its capabil-

ity to represent and deal with vague linguistic expressions. Such expressions

are typical of natural language. A linguistic expression is vague when its

meaning is not fixed by sharp boundaries. Such a linguistic expression is always

associated with uncertainty regarding its applicability. However, this type of

uncertainty does not result from any information deficiency, but from the lack

of linguistic precision. It is a linguistic uncertainty rather than information-

based uncertainty. Consider, for example, a fuzzy set that was constructed in a

given application context to represent the linguistic term “high temperature.”

Assume now that a particular measurement of the temperature was taken (say

92°F). This measurement belongs to the fuzzy set with a particular member-

ship degree (say, 0.7). Clearly, this degree does not express any lack of infor-

mation (the actual value of the temperature is known—it is 92°F), but rather

the degree of compatibility of the known value with the imprecise (vague)

linguistic term.

Since this linguistic uncertainty is represented by fuzzy sets, it is usually

called fuzziness.Each fuzzy set is clearly associated with some amount of fuzzi-

ness, and it is desirable to be able to measure this amount in some meaning-

ful way. Although the amount of fuzziness is not connected in any way to the

quantification of information, it is an important trait of information represen-

tation. Clearly, our ability to measure it allows us to characterize information

representation more completely, and thus enriches our methodological capa-

bilities for dealing with information.

In general, a measure of fuzziness for some type of fuzzy sets is a functional

where F(X ) denotes the set of all fuzzy subsets of X of a given type. Thus far,

however, the issue of measuring fuzziness has been addressed only for stan-

dard fuzzy sets. This restriction is thus followed in this section as well.

fX:,F

()

Æ

+

⺢

8.2. MEASURES OF FUZZINESS 321