Kenny Anthony. Medieval Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

faithful, using as his agents the nations of Gog and Magog. The saints will

endure their suVerings until the onslaughts of Gog and Magog have burnt

themselves out (DCD XX. 11–12. 19). Thirdly, Jesus will return to earth to

judge the living and the dead. Fourthly, in order to be judged, the souls of

the dead will return from their resting place and be reunited with their

bodies. Fifthly, the judgement will separate the virtuous from the vicious,

with the saints assigned to eternal bliss and the wicked to eternal damna-

tion (DCD XX. 22. 27). Sixthly, the present world will be destroyed in a

cosmic conXagration, and a new heaven and a new earth will be created

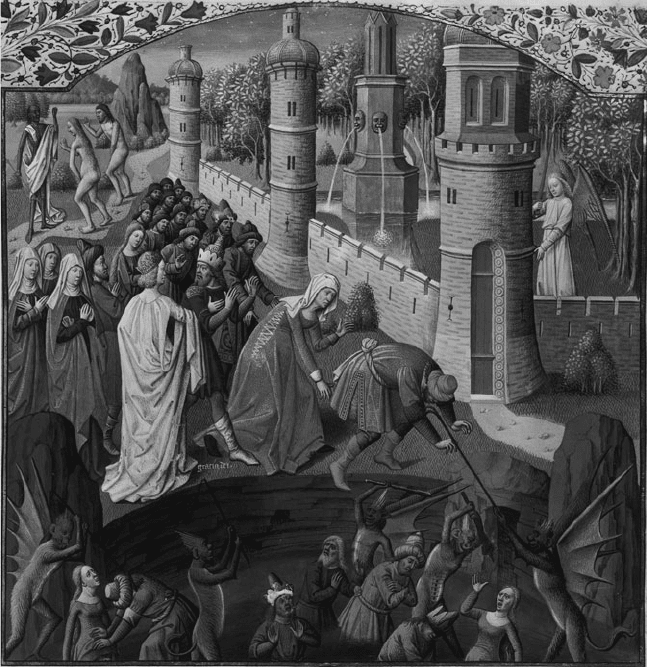

The Massa Damnata . This MS of the City of God shows Adam and Eve meeting death after

expulsion from Eden, and the human race going on its way to Hell while the elect are

saved by divine grace.

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

12

(DCD XX. 16–18). Seventhly, the blessed and the damned will take up the

everlasting abode that has been assigned to them in heaven and in hell

(DCD XX. 30). The heavenly Jerusalem above and the unquenchable Wres

below are the consummation of the two cities of Augustine’s narrative.

Augustine realizes that his predictions are not easy to accept, and he

singles out as the most diYcult of all the idea that the wicked will suVer

eternal bodily punishment. Bodies are surely consumed by Wre, it is

objected, and whatever can suVer pain must sooner or later suVer death.

Augustine replies that salamanders thrive in Wre, and Etna burns for ever.

Souls no less than bodies can suVer pain, and yet philosophers agree that

souls are immortal. There are many wonders in the natural world—

Augustine gives a long list, including the properties of lime, of diamonds,

of magnets, and of Dead Sea fruit—that make it entirely credible that an

omnipotent creator can keep alive for ever a human body in appalling pain

(DCD XXI. 3–7).

Most people are concerned less about the physical mechanism than

about the moral justiWcation for eternal damnation. How can any crime

in a brief life deserve a punishment that lasts for ever? Even in human

jurisprudence, Augustine responds, there is no necessary temporal propor-

tion between crime and punishment. A man may be Xogged for hours to

punish a brief adulterous kiss; a slave may spend years in prison for a

momentary insult to his master (DCD XXI. 11). It is false sentimentality

to believe, out of compassion, that the pains of hell will ever have an end. If

you are tempted by that thought, you may end up believing, like the heretic

Origen, that one day even the Devil will be converted (DCD XXI. 17)!

Step by step Augustine seeks to show not only that eternal punishment

is possible and justiWed, but that it is extremely diYcult to avoid it. A

virtuous life is not enough, for the virtues of pagans without the true faith

are only splendid vices. Being baptized is not enough, for the baptized may

fall into heresy. Orthodox belief is not enough, for even the most staunch

Catholics may fall into sin. Devotion to the sacraments is not enough: no

one knows whether he is receiving them in such a spirit as to qualify for

Jesus’ promises of eternal life (DCD XXI. 19–25). Philanthropy is not

enough: Augustine devotes pages to explaining away the passage in St

Matthew’s Gospel in which the Son of Man separates the sheep from the

goats on the basis of their performance or neglect of works of mercy to

their fellow men (Matt. 25: 31–46; DCD XXI. 27).

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

13

And so at last, in the twenty-second book of The City of God, we come to

the everlasting bliss of the saints in the New Jerusalem. To those who doubt

whether earthly bodies could ever dwell in heaven, Augustine oVers the

following highly Platonic reply:

Suppose we were purely souls, spirits without any bodies, and lived in heaven

without any contact with terrestrial animals. If someone said to us that we were

destined to be joined to bodies by some mysterious link in order to give life to

them, would we not refuse to believe it, arguing that nature does not allow an

incorporeal entity to be bound by a corporeal tie? Why then cannot a terrestrial

body be raised to a heavenly body by the will of God who made the human

animal? (DCD XXII. 4)

No Christian can refuse to believe in the possibility of a celestial human

body, since all accept that Jesus rose from the dead and ascended into

heaven. The life everlasting promised to the blessed is no more incredible

than the story of Christ’s resurrection.

It is incredible that Christ rose in the Xesh and went up into heaven with his

Xesh. It is incredible that the world believed so incredible a story, and it is

incredible that a few men without birth or position or experience should have

been able to persuade so eVectively the world and the learned world. Our

adversaries refuse to believe the W rst of these three incredible things, but they

cannot ignore the second, and they cannot account for it unless they accept the

third. (DCD XXII. 5)

To show that all these incredible things are in fact credible, Augustine

appeals to divine omnipotence, as exhibited in a series of miracles that have

been observed by himself or eyewitnesses among his friends. But he accepts

that he has to answer diYculties raised by philosophical adversaries against

the whole concept of a bodily resurrection.

How can human bodies, made of heavy elements, exist in the ethereal

sublimity of heaven? No more problem, says Augustine, than birds Xying in

air or Wre breaking out on earth. Will resurrected bodies all be male? No:

women will keep their sex, though their organs will no longer serve for

intercourse and childbirth, since in heaven there will no longer be marriage.

Will resurrected bodies all have the same size and shape? No: everyone will

be given the stature they had at maturity (if they died in old age) or the

stature they would have had at maturity (if they died young). What of those

who died as infants? They will reach maturity instantaneously on rising.

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

14

All resurrected bodies will be perfect and beautiful: the resurrection will

involve cosmetic surgery on a cosmic scale. Deformities and blemishes will

be removed; amputated limbs will be restored to amputees. Shorn hair and

nail clippings will return to form part of the body of their original owners,

though not in the form of hair and nails. ‘Fat people and thin people need

not fear that in that world they will be the kind of people that they would

have preferred not to be while in this world’ (DCD XXII. 19).

Augustine raises a problem that continued to trouble believers in every

century in which belief in a Wnal resurrection was taken seriously. Suppose

that a starving man relieves his hunger by cannibalism: to whose body, at the

resurrection, will the digested human Xesh belong? Augustine gives a care-

fully thought-out answer. Before A gets so hungry that he eats the body of B,

A must have lost a lot of weight—bits of his body must have been exhaled

into the air. At the resurrection this material will be transformed back into

Xesh, to give A the appropriate avoirdupois, and the digested Xesh will be

restored to B. The whole transaction should be looked on as parallel to the

borrowing of a sum of money, to be returned in due time (DCD XXII. 30).

But what will the blessed do with these splendid risen bodies? Augustine

confesses, ‘to tell the truth, I do not know what will be the nature of their

activity—or rather of their rest and leisure’. The Bible tells us that they will

see God: and this sets Augustine another problem. If the blessed cannot

open and shut their eyes at will, they are worse oV than we are. But how

could anyone shut their eyes upon God? His reply is subtle. In that blessed

state God will indeed be visible, to the eyes of the body and not just to the

eyes of the mind; but he will not be an extra object of vision. Rather we will

see God by observing his governance of the bodies that make up the

material scheme of things around us, just as we see the life of our fellow

men by observing their behaviour. Life is not an extra body that we see, and

yet when we see the motions of living beings we do not just believe they are

alive, we see they are alive. So in the City of God we will observe the work of

God bringing harmony and beauty everywhere (DCD XXII. 30).

Though it is dependent on the Bible on almost every page, The City of God

deserves a signiWcant place in the history of philosophy, for two reasons. In

the Wrst place, Augustine constantly strives to place his religious world-

view into the philosophical tradition of Greece and Rome: where possible

he tries to harmonize the Bible with Plato and Cicero; where this is not

possible he feels obliged to recite and refute philosophical anti-Christian

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

15

arguments. Secondly, the narrative Augustine constructed out of biblical

and classical elements provided the framework for philosophical discussion

in the Latin world up to and beyond the Renaissance and the Reformation.

Augustine was one of the most interesting human beings ever to have

written philosophy. He had a keen and lively analytic mind and at his best

he wrote vividly, wittily, and movingly. Unlike the philosophers of the

high Middle Ages, he takes pains to illustrate his philosophical points with

concrete imagery, and the examples he gives are never stale and ossi W ed as

they too often are in the texts of the great scholastics. In the service of

philosophy he can employ anecdote, epigram, and paradox, and he can

detect deep philosophical problems beneath the smooth surface of lan-

guage. He falls short of the very greatest rank in philosophy because he

remains too much a rhetorician: to the end of his life he could never really

tell the diVerence between genuine logical analysis and mere linguistic

pirouette. But then once he was a bishop his aims were never purely

philosophical: both rhetoric and logic were merely instruments for the

spreading of Christ’s gospel.

The Consolations of Boethius

In the Wfth century the Roman Empire experienced an age of foreign

invasion (principally in the West) and of theological disputation (princi-

pally in the East). Augustine’s City of God had been occasioned by the sack of

Rome by the Visigoths in 410; in 430, when he died in Hippo, the Vandals

were at the gates of the city. Augustine’s death prevented him from

accepting an invitation to attend a Church council in Ephesus. The

Council had been called by the emperor Theodosius II because the patri-

archates of Constantinople and Alexandria disagreed violently about how

to formulate the doctrine of the divine sonship of the man Jesus Christ.

In the course of the c entury the Goths and the Vandals were succeeded

by an even more fearsome group of invaders, the Huns, under their king

Attila. Attila conquered vast areas from China to the Rhine before being

fought to a standstill in Gaul in 451 by a Roman general in alliance with a

Gothic king. In the following year he invaded Italy, and Rome was saved

from occupation only by the eVorts of Pope Leo the Great, using a mixture

of eloquence and bribery.

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

16

The Council of Ephesus in 431 condemned Nestorius, the bishop of

Constantinople, because he taught that Mary, the mother of Jesus, was not

the mother of God. How could he hold this, the Alexandrian bishop Cyril

argued, if he really believed that Jesus was God? The right way to formulate

the doctrine of the Incarnation, the Council decided, was to say that

Christ, a single person, had two distinct natures, one divine and one

human. But the Council did not go far enough for some Alexandrians,

who believed that the incarnate Son of God possessed only a single nature.

These extremists arranged a second council at Ephesus, which proclaimed

the doctrine of the single nature (‘monophysitism’). Pope Leo, who had

submitted written evidence in favour of the dual nature, denounced the

Council as a den of robbers.

Heartened by the support of Rome, Constantinople struck back at

Alexandria, and at a council at Chalcedon in 451 the doctrine of the dual

nature was aYrmed. Christ was perfect God and perfect man, with a human

body and a human soul, sharing divinity with his Father and sharing

humanity with us. The decisions of Chalcedon and Wrst Ephesus henceforth

provided the test of orthodoxy for the great majority of Christians, though

in eastern parts of the empire substantial communities of Nestorian and

monophysite Christians remained, some of which have survived to this day.

In the history of thought the importance of these Wfth-century councils is

that they hammered out technical meanings for terms such as ‘nature’ and

‘person’ in a manner that inXuenced philosophy for centuries to come.

After the repulse of Attila the western Roman Empire survived a further

quarter of a century, though power in Italy had largely passed to barbarian

army commanders. One of these, Odoacer, in 476, decided to become ruler

in name and not just in fact. He sent oV the last faine

´

ant emperor,

Romulus Augustulus, to exile near Naples. For the next half-century

Italy became a Gothic province. Its kings, though Christians, took little

interest in the recent Christological debates: they subscribed to a form of

Christianity, namely Arianism, that had been condemned as long ago as

the time of Constantine I. Arianism took various forms, all of which denied

that Jesus, the Son of God, shared the same essence or substance with God

the Father. The most vigorous of the Gothic kings, Theodoric (reigned

493–526), established a tolerant regime in which Arians, Jews, and Ortho-

dox Catholics lived together in tranquillity and in which art and culture

thrived.

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

17

Boethius with his father-in-law Symmachus, from a ninth century manuscript of his

treatise on arithmetic.

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

18

One of Theodoric’s ministers was Manlius Severinus Boethius, a member

of a powerful Roman senatorian family. Born shortly after the end of the

Western Empire, he lost his father in childhood and was adopted into the

family of the consul Symmachus, whose daughter he later married. He

himself became consul in 510 and saw his two sons become consuls in 522.

In that year Boethius moved from Rome to Theodoric’s capital at Ravenna,

to become ‘master of oYces’, a very senior administrative post which he

held with integrity and distinction.

As a young man Boethius had written handbooks on music and math-

ematics, drawn from Greek sources, and he had proj ected, but never

completed, a translation into Latin of the entire works of Plato and

Aristotle. He wrote commentaries on some of Aristotle’s logical works,

showing some acquaintance with Stoic logic. He wrote four theological

tractates dealing with the doctrines of the Trinity and the Incarnation,

showing the inXuence both of Augustine and of the Wfth-century Christo-

logical debates. His career appeared to be a model for those who wished to

combine the contemplative and active lives. Gibbon, who could rarely

bring himself to praise a philosopher, wrote of him, ‘Prosperous in his fame

and fortunes, in his public honours and private alliances, in the cultivation

of science and the consciousness of virtue, Boethius might have been styled

happy, if that precarious epithet could be safely applied before the last term

of the life of man’ (Decline and Fall, ch. 19).

Boethius, however, did not hold his honourable oYce for long, because

he fell under suspicion of being implicated, as a Catholic, in treasonable

correspondence urging the emperor Justin at Constantinople to invade

Italy and end Arian rule. He was imprisoned in a tower in Pavia and

condemned to death by the senate in Rome. It was while he was in prison,

under sentence of death, that he wrote the work for which he is most

remembered, On the Consolation of Philosophy. The work has been admired

for its literary beauty as well as for its philosophical acumen; it has been

translated many times into many languages, notably by King Alfred and

by Chaucer. It contains a subtle discussio n of the problems of relating

human freedom to divine foreknowledge; but it is not quite the kind

of work that might be expected from a devout Catholic facing possible

martyrdom. It dwells on the comfort oVered by pagan philosophy,

but there is no reference to the consolations held out by the Christian

religion.

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

19

At the beginning of the work Boethius describes how he was visited in

prison by a tall woman, elderly in years but fair in complexion, clothed in

an exquisitely woven but sadly tattered garment: this was the Lady Phil-

osophy. On her dress was woven a ladder, with the Greek letter P at its foot

and the Greek letter TH at its head: these meant the Practical and

Theoretical divisions of Philosophy and the ladder represented the steps

between the two. The lady’s Wrst act was to eject the muses of poetry,

represented by Boethius’ bedside books; but she was herself willing to

provide verses to console the aZicted prisoner. The Wve books of the

Consolation consist of alternating passages of prose and poetry. The poems

vary between sublimity and doggerel; it often takes a considerable eVort to

detect their relevance to the developing prose narrative.

In the Wrst book Boethius defends himself against the charges that have

been brought against him. His troubles have all come upon him because

he entered public oYce in obedience to Plato’s injunction to philosophers

to involve themselves in political aVairs. Lady Philosophy reminds him that

he is not the Wrst philosopher to suVer: Socrates suVered in Athens and

Seneca in Rome. She herself has been subject to outrage: her dress is

tattered because Epicureans and Stoics tried to kidnap her and tore her

clothes, carrying oV the torn-oV shreds. She urges Boeth ius to remember

that even if the wicked prosper, the world is subject not to random

chance but to the governance of divine reason. The book ends with a

poem that looks rather like a shred torn oV by a Stoic, urging rejection of

the passions.

Joy you must banish

Banish too fear

All grief must vanish

And hope bring no cheer.

The second book, too, develops a Stoic theme: matters within the

province of fortune are insigniWcant by comparison with values within

oneself. The gifts of fortune that we enjoy do not really belong to us: riches

may be lost, and are most valuable when we are giving them away. A

splendid household is a blessing to me only if my servants are honest, and

their virtue belongs to them not me. Political power may end in murder or

slavery; and even while it is possessed it is trivial. The inhabited world is

only a quarter of our globe; our globe is minute in comparison with the

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

20

celestial sphere; for a man to boast of his power is like a mouse crowing

over other mice. The greatest of fame lasts only a few years that add up to

zero in comparison with never-ending eternity. I cannot Wnd happiness in

wealth, power, or fame, but only in my most precious possession, myself.

Boethius has no real ground of complaint against fortune: she has given

him many good things and he must accept also the evil which she sends.

Indeed, ill fortune is better for men than good fortune. Good fortune is

deceitful, constant only in her inconstancy; bad fortune brings men self-

knowledge and teaches them who are their true friends, the most precious

of all kinds of riches.

The message that true happiness is not to be found in external goods is

reinforced in the third book, developing material from Plato and Aristotle:

happiness (beatitudo) is the good which, once achieved, leaves nothing further to be

desired. It is the highest of all goods, containing all goods with itself; if any good

was lacking to it, it could not be the highest good since there would be something

left over to be desired. So happiness is a state which is made perfect by the

accumulation of all the goods there are. (DCP 3. 2)

Wealth, honour, power, glory do not fulWl these conditions, nor do the

pleasures of the body. Some bodies are very beautiful, but if we had X-ray

eyes we would Wnd them disgusting. Marriage and its pleasures may be a

Wne thing, but children are little tormentors. We must cease to look to the

things of this world for happiness. God, Lady Philosophy argues, is the best

and most perfect of all good things; but the perfect good is true happiness;

therefore, true happiness is to be found only in God. All the values that are

sought separately by humans in their pursuit of mistaken forms of happi-

ness—self-suYciency, power, respect, pleasure—are found united in the

single goodness of God. God’s perfection is extolled in the ninth poem of

the third book, O qui perpetua: a hymn often admired by Christians, though

almost all its thoughts are take n from Plato’s Timaeus and a Neoplatonic

commentary thereon.4 Because all goodness resides in God, humans can

only become happy if, in some way, they become gods. ‘Every happy man is

a god. Though by nature God is one only; but nothi ng prevents his divinity

from being shared by many’ (DCP 3. 10).

4 In Chaucer’s (prose) translation it commences: ‘O thou father, creator of heaven and of

earth, that governest this world by perdurable reason, that commandest the times to go from

since that age had its beginning: thou that dwellest thyself aye steadfast and stable, and givest all

other things to be moved . . . ’.

PHILOSOPHY AND FAITH

21