Kenny Anthony. Medieval Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Human freedom operated unhindered before the Fall: that is one reason

for the gravity of Adam’s sin. But when Adam fell, his sin brought with it

not only liability to death, disease, and pain, but in addition massive moral

debilitation. We children of Adam inherit not only mortality but also

sinfulness. Corrupt humans tainted with original sin have no freedom to

live well without hel p: each temptation, as it comes, we may be free to resist,

but our resistance cannot be prolonged from day to day. We need God’s

grace not only to gain heaven but to avoid a life of continual sin (DCG 7).

The grace that enables human beings to avoid sin is allotted to some

people rather than others not on the basis of any merit of theirs, whether

actual or foreseen. It is awarded simply by the inscrutable good pleasure of

God. No one can be saved without being predestined. The choice of those

who are to be saved, and implicitly also of those who are to be damned, was

made by God long before they had come into existence or done any deeds

good or bad.

The relation between divine predestination and human virtue and vice

was a topic that occupied Augustine’s last years. A British ascetic named

Pelagius, who came Wrst to Rome, and then after its sack to Africa,

preached a view of human freedom quite in conXict with Augustine’s.

The sin of Adam, he taught, had not damaged his heirs except by setting

them a bad example; human beings, throughout their history, retained full

freedom of the will. Death was not a punishment for sin but a natural

necessity, and even pagans who had lived virtuously enjoyed a happy

afterlife. Christians had received the special grace of baptism, which en-

titled them to the superior happiness of heaven. Such special graces were

allotted by God to those he foresaw would deserve them.

Augustine secured the condemnation of Pelagius at a council at Car-

thage in 418 (DB 101–8) but that was not the end of the matter. Devout

ascetics in monasteries in Africa and France complained that if Augustine’s

account of freedom was correct, then exhortation and rebuke were vain

and the whole monastic discipline was pointless. Why should an abbot

rebuke an erring monk? If the monk was predestined to be better, then

God would make him so; if not, the monk would continue in sin no

matter what the abbot said. In response, Augustine insisted that not only

the initial call to Christianity, the Wrst stirring of faith, was a matter of sheer

grace; so too was the perseverance in virtue of the most devout Christian

approaching death (DCG 7; DDP).

GOD

282

If grace was necessary for salvation, was it also suYcient? If you are

oVered grace, can you resist it? If so, then there would be some scope for

freedom in human destiny. While some would end up in hell because they

had never been oVered grace, hell would also contain those who had been

oVered grace and turned it down. In the course of controversy Augustine’s

position continually hardened, and in the end he denied even this vestige

of human choice: grace cannot be declined , cannot be overcome. There are

only two classes of people: those who have been given grace and those who

have not, the predestined and the reprobate. We can give no reason why

any individual falls in one class rather than another.

If we take two babies, equally in the bonds of original sin, and ask why one is taken

and the other left; if we take two sinful adults, and ask why one is called and the

other not; in each case the judgements of God are inscrutable. If we take two holy

men, and ask why the gift of perseverance to the end is given to one and not to the

other, the judgements of God are even more inscrutable. (DDP 66)

The crabbed crusader of predestination in the monastery at Hippo is very

diVerent from the youthful defender of human freedom in the gardens of

Cassiciacum. It was the former, and not the latter, whose inXuence was

powerful after his death and cast a shadow over centuries to come.

Boethius on Divine Foreknowledge

The problem that faced Augustine in reconciling human freedom with the

power of God can be solved if one is willing to jettison the doctrine of

predestination. But for all those who believe that God is omniscient there

remains a problem about divine foreknowledge: this concerns not God’s

willing humans to act virtuously and be saved, but simply God’s knowing what

humans will or will not do. This problem was discussed in a clear and

energetic fashion in the Wfth book of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy.

The book addresses the question: in a world governed by divine provi-

dence, can there be any such thing as luck or chance? Lady Philosophy says

that if by chance we mean an event produced by random motion without

any chain of causes, then there is no such thing as chance. The only kind of

chance is that deW ned by Aristotle as the unexpected eVect of coinciding

causes (DCP 5. 1). In that case, Boethius asks, does the causal network leave

GOD

283

any room for free human choice or does the chain of fate bind even the

motions of our minds? The diYculty is this. If God foresees all, and cannot

be in error, then what he foresees must happen of necessity. For if it is

possible for our deeds and desires to turn out in any way other than God

has foreseen, then it is possible for God to be in error. Even if in fact all

turns out as he foresaw, his foresight can only have been conjecture, not

true knowledge.

Boethius admits that knowledge does not, in itself, cause what is known.

You may know that I am sitting, but it is my sitting that causes your

knowledge, not your knowledge that causes my sitting. But necessity is

diVerent from causality; and ‘If you know that I am sitting, then I am

sitting’ is a necessary truth. So, too, ‘If God knows that I will sin, I will sin’ is

a necessary truth. Surely that is enough to destroy our free will, and with it

all justiWcation for reward or punishment for human actions. On the ot her

hand, if it is still possible for me not to sin, and God thinks that I will

inevitably sin, then he is in error—a blasphemous suggestion!

Lady Philosophy accepts that a genuinely free action cannot be foreseen

with certainty. But we can observe, without any room for doubt, some-

thing happening in the present. When we watch a charioteer steering his

horses round a racetrack, neither our vision nor anything else necessitates

his skilful management of his team. God’s knowledge of our future actions

is like our knowledge of others’ present actions: he is outside time, and his

seeing is not really a foreseeing. ‘The same future event, when it is related to

divine knowledge, is necessary; but when it is considered in its own nature

can be seen to be utterly free and unconditioned . . . God beholds as present

those future events that happen because of freewill’ (DCP 5. 6).

There are two kinds of necessity: plain straightforward necessity, as in

‘Necessarily all men are mortal’, and conditional necessity as in ‘Necessarily

if you know that I am walking, I am walking’. Conditional necessity does

not bring with it plain necessity: we cannot infer ‘If you know I am

walking, necessarily I am walking’. Accordingly, the future events that

God sees as present are conditionally necessary, but they are not necessary

in the straightforward sense that matters when we are talking of the

freedom of the will (DCP 5. 6).

While explaining that God is outside time, Boethius produced a deWni-

tion of eternity that became canonical. ‘Eternity is the whole and perfect

possession, all at once, of endless life’ (DCP 5. 6). We who live in time

GOD

284

proceed from the past into the future; we have already lost yesterday and

we have not yet reached tomorrow. But God possesses the whole of his life

simultaneously; none of it has Xowed into the past and none of it is still

waiting in the wings.

Boethius’ treatment of freedom, foreknowledge, and eternity became

the classical account for much of the Middle Ages. But problems remain

with his solution of the dilemma he posed with such unparalleled clarity.

Surely, matters really are as God sees them; so if God sees tom orrow’s sea-

battle as present, then it really is present already. Again, the notion of

eternity raises more problems than it solves. If Boethius’ imprisonment is

simultaneous with God’s eternity, and God’s eternity is simultaneous

with the sack of Troy, does that not mean that Boethius was imprisoned

while Troy was burning? We cannot say that the imprisonment is simul-

taneous with one part of eternity, and the sack with another part, because

eternity has no parts but, on the Lady Philosophy’s account, happens all

at once.2

Negative Theology in Eriugena

Scotus Eriugena, two centuries later, returned to the Augustinian problem

of predestination,3 but his principal contribution to philosophical theology

lay in the extremely restrictive account which he gives of the use of

language about God. God is not in any of Aristotl e’s categories, so all the

things that are can be denied of him—that is, negative (‘apophatic’)

theology. On the other hand, God is the cause of all the things that are,

so they can all be aYrmed of him: we can say that God is goodness, light,

etc.—that is, positive (‘cataphatic’) theology. But all the terms that we

apply to God are applied to him only improper ly and metaphorically. This

applies just as much to words like ‘good’ and ‘just’ as to more obviously

metaphorical descriptions of God as a rock or a lion. We can see this when

we reXect that such predicates have an opposite, but God has no opposite.

Because aYrmative theology is merely metaphorical it is not in conXict

with negative theology, which is literally true.

2 See my The God of the Philosophers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), 38–48.

3 See above, p. 282.

GOD

285

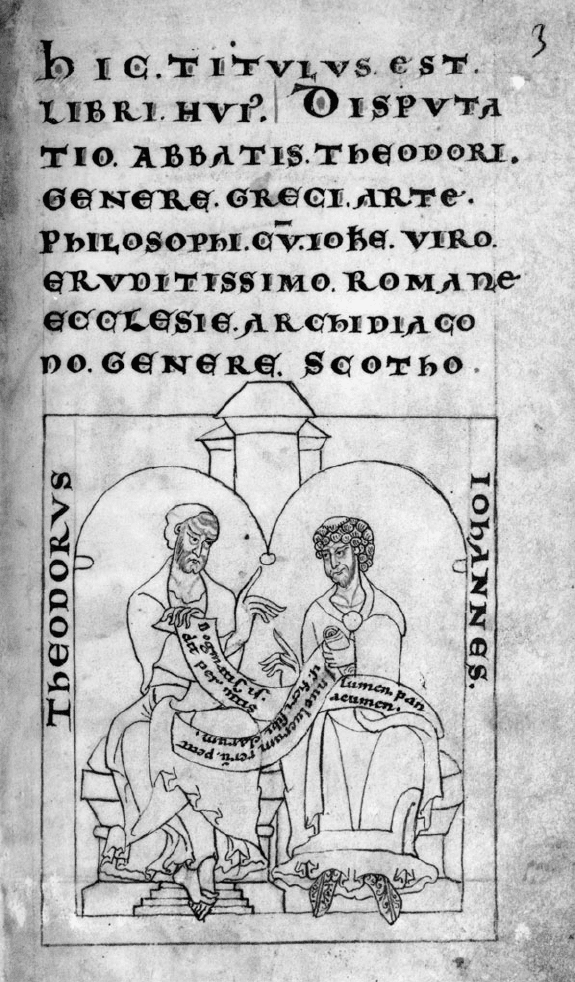

John Scotus Eriugena (on the right) disputing with a Greek abbot Theodore.

GOD

286

According to Eriugena, God is not good but more than good, not wise

but more than wise, not eternal but more than eternal. This language, of

course, does not really add anything, except a tone of awe, to the denial

that any of these predicates are literally true of God. Eriugena even goes

as far as to say that God is not God but more than God. So too with

the individual persons of the Trinity: the Father is not a Father except

metaphorically.

Among the Aristotelian categories that, according to Eriugena, are to be

denied of God are those of action and passion. God neither acts nor is acted

upon, except metaphorically: strictly he neither moves nor is moved,

neither loves nor is loved. The Bible tells us that God loves and is loved,

but that has to be interpreted in the light of reason. Reason is superior to

authority; authority is derived from reason and not vice versa; reason does

not require any conW rmation from authority. Reason tells us that the Bible

is not using nouns and verbs in their proper sense, but using allegories and

metaphors to go to meet our childish intelligence. ‘Nothing can be said

properly about God, since he surpasses every intellect, who is better known

by not knowing, of whom ignorance is the true knowledge, who is more

truly and faithfully denied in all things than aYrmed’ (Periphyseon, 1).

Our knowledge of God, such as it is, is derived both from the metaphor-

ical statements of theology and from ‘theophanies’, or manifestations of

God to particular persons, such as the visions of the prophets. God’s

essence is unknown to men and angels: indeed, it is unknown to God

himself. Just as I, a human being, know that I am, but not what I am, so God

does not know what he is. If he did, he would be able to deW ne himself; but

the inWnite cannot be deWned. It is no insult to God to say that he does not

know what he is; for he is not a what (Periphyseon, 2).

In describing the relation between God and his creatures Eriugena uses

language which is easily interpreted as a form of pantheism, and it was this

that led to his condemnation by a Pope three and a half centuries later.

God, he says, may be said to be created in creatures, to be made in the

things he makes, and to begin to be in the things that begin to be

(Periphyseon, 1. 12). Just as our intellect creates its own life by engaging in

actual thinking, so too God, in giving life to creatures, is making a life for

himself. To those who regarded such statements as Xatly incompatible with

Christian orthodoxy, Eriugena could no doubt have replied that, like all

other positive statement s about God, they were only metaphors.

GOD

287

Eriugena took his ideas of negative and positive theology from pseudo-

Dionysius, but he developed those ideas in a novel and adventurous

way. His work reaches a level of agnosticism not to be paralleled

among Christian philosophers for centuries to come. His manner of

approaching the realm of religious mystery will not be seen again in the

history of philosophy until we encounter Nicholas of Cusa in the Wfteenth

century.

Islamic Arguments for God’s Existence

Meanwhile, in the Islamic world philosophers were taking a more robust

attitude to natural theology. Eriugena’s contemporary al-Kindi was pre-

pared to oVer a series of elaborate and systematic proofs for the existence of

God, based on establishing the Wnite nature of the world we live in. In his

First Philosophy, drawing on some of the arguments of John Philoponus,

known to Arabs as Yahya al-Nahwi, al-Kindi proceeds as follows.

Suppose that the physical world were inW nite in quantity. If we take out

of it a Wnite quantity, is what is left Wnite or inWnite? If Wnite, then if we

restore what has been taken out, we have only a Wnite quantity, since the

addition of two Wnite quantities cannot make an inWnite one. If in Wnite,

then if we restore what has been taken out, we will have two inWnite bodies,

one (the original) smaller than the other (the restored whole). But this is

absurd. So the universe must be Wnite in space.

Similar considerations show that the universe is Wnite in time. Time is

quantitative, and an actually inWnite quantity cannot exist. If time were

inWnite, then an inWnite number of prior times must have preceded the

present moment. But an inWnite number cannot be traversed; so if time

were inWnite we would never have got to the present moment, which is

absurd.

If time is Wnite, then the universe must have had a beginning in time; for

the universe cannot exist without time. But if the universe had a beginning,

then it must have had a cause other than itself. This cause must be the

cause of the multiplicity to be found in the universe, and this al-Kindi calls

the True One. This, he tells us is the cause of the beginning of coming to be

in the universe, and is the cause of the unity that holds each creature

together. ‘The True One is therefore the First, the Creator who holds

GOD

288

everything he has created, and whatever is freed from his hold and power

reverts and perishes.’4

Christians as well as Muslims found it convenient that philosophical

arguments could be oVered for the creation of the world in time, so that

the believer did not need to take this simply on faith, on the authority of

Genesis or the Quran. The arguments which al-Kindi brought into Islam

from Philoponus returned into the Christian world in the high Middle

Ages, and their validity, as we shall see, became a matter of debate among

the major scholastics.

Not all Muslim philosophers agreed that the world was created in time.

Avicenna believed that God created by necessity: he is absolute goodness,

and goodness by its nature radiates outwards. But if God is necessarily a

creator, then creation must be eternal just as God is eternal. But though

the material world is coeternal with God, it is nonetheless caused by God—

not directly, but via the successive emanation of intelligences that culmin-

ates in the tenth intelligence that is the creator of matter and the giver of

forms.5

Though the world is eternal, it is still possible to prove the existence of

God by a consideration of contingency and necessity. For Avicenna there is

a sense in which all things are necessary, since everything is a necessary

creation of an eternal God. But there is an important distinction to be

made between things that exist necessarily of themselves and those that,

considered in themselves, are contingent. Starting with this distinction,

Avicenna oVers a proof that there must be at least one thing that is

necessarily existent of itself.

Start with any entity you choose—it can be anything in heaven or on

earth. If this is necessarily existent of itself, then our thesis is proved. If it is

contingently existent of itself, then it is necessarily existent through

something else. This second entity is necessarily existent either of itself,

or through something else. If through something else, then there is a third

entity, and so on. However long the series is, it cannot end with something

that is of itself contingent; for that, and thus the whole series, would need a

cause to explain its existence. Even if the complete causal series is inWnite, it

must contain at least one cause that is necessarily existent of itself, because

4 See William Lane Craig, The Kalam Cosmological Argument (London: Macmillan, 1979), 19–36.

5 See above, p. 224.

GOD

289

if it contained only contingent causes it would need an external cause and

thus not be complete.

To show that a being necessarily existent of itself is God, Avicenna has to

prove that such a being (which he henceforth calls, for short, ‘necessary

being’) must possess the deWning attributes of divinity. In the seventh

section of the Wrst tractate of his Metaphysics Avicenna argues that there

can be at most one necessary being; in the eighth tractate he develops the

other attributes of the unique necessary being. It is perfect, it is pure

goodness, it is truth, it is pure intelligence; it is the source of everything

else’s beauty and splendour (Metaph. 8. 368).

The most important feature of the necessary being is that it does not

have an essence which is other than its existence.6 If it did, there would

have to be a cause to unite the essence with the existence, and the necessary

being would be not necess ary but caused. Since it has no essence other than

its existence, we can say that it does not have an essence at all, but is pure

being. And if it does not have an essence, then it does not belong in any

genus: God and creatures have nothing in common and ‘being’ cannot be

applied to necessary and contingent being in the same sense. Since essence

and quiddity are the same, the supreme being does not have a quiddity:

that is to say, there is no answer to the question ‘What is God?’ (Metaph.8.

344–7).

Anselm’s Proof of God

Avicenna’s natural theology was enormously fertile: theories to be found

in philosophers of religion during the succeeding ten centuries can often to

be shown to be (often unwitting) developments of ideas that are Wrst found

in his writings. But one theologian whose ideas bear a remarkable resem-

blance to his had certainly never read him. This was Anselm, who was born

four years before Avicenna’s death, and who died forty years before

Avicenna’s works were translated into Latin.

6 The Arabic word for existence, ‘anniya’, is translated into Latin as ‘anitas’—it is what

answers to the question ‘An est ¼ ‘Is there a...?’just as quidditas is what answers to ‘Quid est’

¼ ‘What is a...?’ ‘Anity’ has never taken out English citizenship as ‘Quiddity’ has; if one

wanted to coin a word it would have to be ‘ifness’—what tells us if there is a God.

GOD

290

Anselm’s Proslogion, in a twelfth century manuscript copy.

GOD

291