Jan Lindhe. Clinical Periodontology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

NON-PLAQUE INDUCED INFLAMMATORY GINGIVAL LESIONS • 273

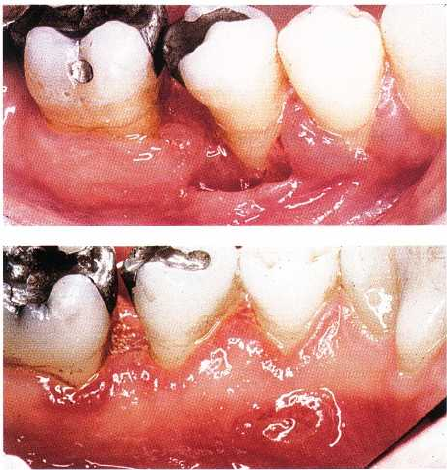

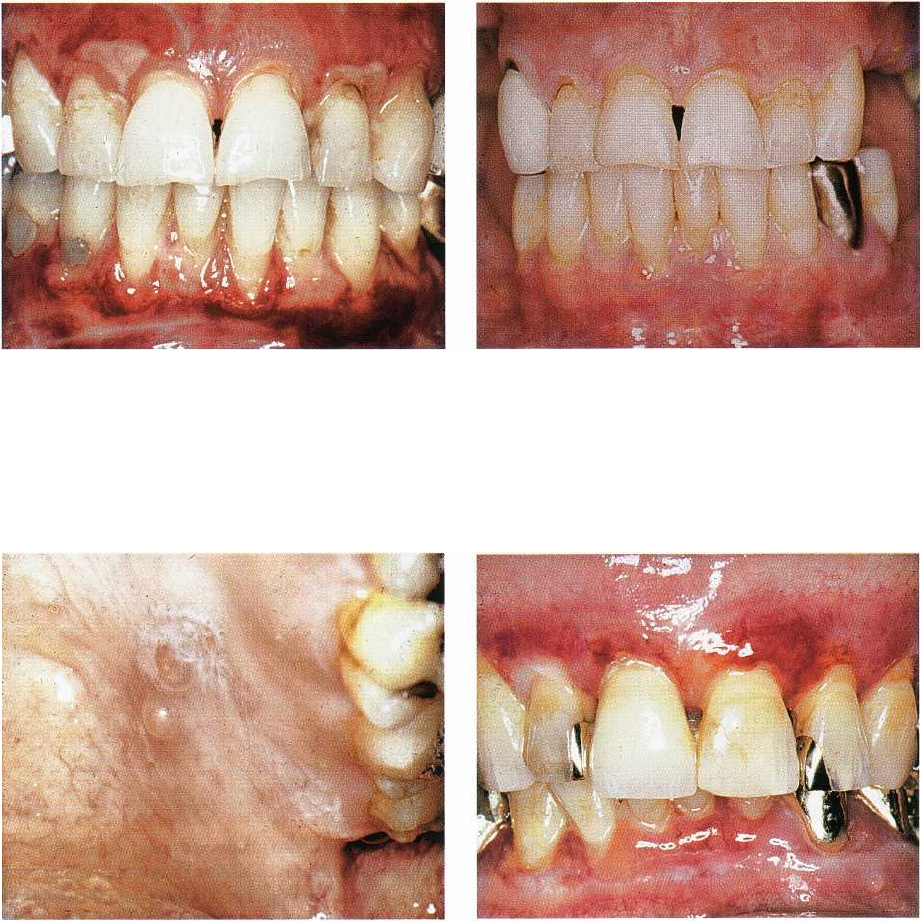

Fig. 12-8. Erythematous candidosis of attached

mandibular gingiva of HIV seropositive mucosa. The

mucogingival junction is invisible.

Fig. 12-7. Pseudomembranous candidosis of maxillary

gingiva and mucosa in HIV seropositive patient. The le

sions can be scraped off, leaving a slightly bleeding

surface.

host defense posture (Holmstrup & Johnson 1997),

including immunodeficiency (Holmstrup & Sama-

ranayake 1990) (Figs. 12-7 and 12-8), reduced saliva

secretion, smoking and treatment with corticoste-

roids, but may be due to a wide range of predisposing

factors. Disturbances in the oral microbial flora, such

as after therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics, may

also lead to oral candidosis. The predisposing factors

are, however, often difficult to identify. Based on their

site, infections may be defined as superficial or sys-

temic. Candidal infection of the oral mucosa is usually

a superficial infection, but systemic infections are not

uncommon in debilitated patients.

In otherwise healthy individuals, oral candidosis

rarely manifests in the gingiva. This is surprising

when considering the fact that C.

albicans

is frequently

isolated from the subgingival flora of patients with

severe periodontitis (Slots et al. 1988). The most com-

mon clinical characteristic of gingival candidal infec-

tions is redness of the attached gingiva often associ-

ated with a granular surface (Fig. 12-10).

Various types of oral mucosal manifestations are

pseudomembranous candidosis (also known as thrush

in neonates), erythematous candidosis, plaque-type

candidosis, and nodular candidosis (Holmstrup &

Axell 1990). Pseudomembranous candidosis shows

whitish patches (Fig. 12-7), which can be wiped off

the mucosa with an instrument or gauze leaving a

slightly bleeding surface. The pseudomembranous

type usually has no major symptoms. Erythematous

lesions can be found anywhere in the oral mucosa (

Fig. 12-10). The intensely red lesions are usually

associated with pain, sometimes even severe. The

plaque-type of oral candidosis is a whitish plaque,

which cannot be removed. There are usually no symp-

toms and the lesion is clinically indistinguishable

from oral leukoplakia. Nodular candidal lesions are

infrequent in the gingiva. Slightly elevated nodules of

Fig. 12-9. Same patient as shown in Fig. 12-8 after topi-

cal antimycotic therapy. The mucogingival junction is

visible.

Fig. 12-10. Chronic erythematous candidosis of maxil

lary attached gingiva of the incisor region.

white or reddish color characterize them (Holmstrup

& Axell 1990).

A diagnosis of candidal infection can be accom-

plished on the basis of culture, smear and biopsy. A

culture on Nickersons medium at room temperature is

easily handled in the dental premises. Microscopic

examination of smears from suspected lesions is an-

other easy diagnostic procedure, either performed as

274 • CHAPTER 12

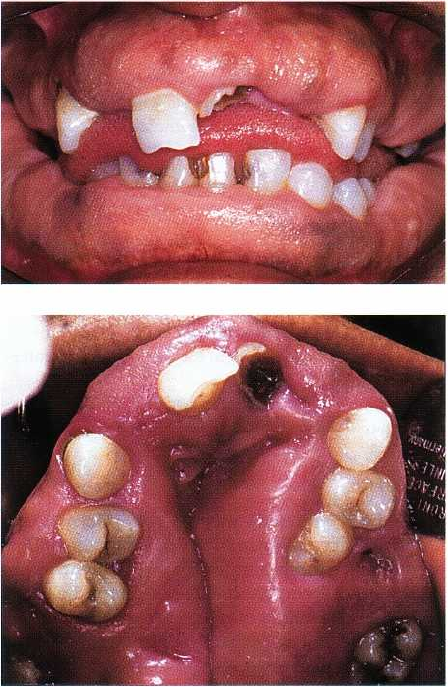

Fig. 12-11. Linear gingival erythema of maxillary

gingiva. Red banding along the gingival margin,

which does not respond to conventional therapy.

direct examination by phase contrast microscopy or as

light microscopic examination of periodic-acid-Schiff-

stained or Gram-stained smears. Mycelium forming

cells in the form of hyphae or pseudohyphae and

blastospores are seen in great numbers among masses

of desquamated cells. Since oral carriage of C.

albicans

is common among healthy individuals, positive cul-

ture and smear does not necessarily imply candidal

infection (Rindum et al. 1994). Quantitative assess-

ment of the mycological findings and the presence of

clinical changes compatible with the above types of

lesions is necessary to obtain a reliable diagnosis,

which can also be obtained on the basis of identifica-

tion of hyphae or pseudohyphae in biopsies from the

lesions.

Topical treatment involves application of antifun-

gals, such as nystatin, amphotericin B or miconazole.

Nystatin may be used as an oral suspension. Since it

is not resorbed it can be used in pregnant or lactating

women. Miconazole exists as an oral gel. It should not

be given during pregnancy and it can interact with

anticoagulants and phenytoin. The treatment in the

severe or generalized forms also involves systemic

antifungals such as fluconazole.

Linear gingival erythema

Linear gingival erythema (LGE) is regarded as a gin-

gival manifestation of immunosuppression charac-

terized by a distinct linear erythematous band limited

to the free gingiva (Consensus Report 1999) (Fig. 12-

11). It is characterized by a disproportion of inflamma

tory intensity for the amount of plaque present. There

is no evidence of pocketing or attachment loss. A

further characteristic of this type of lesion is that it

does not respond well to improved oral hygiene or to

scaling (EC Clearinghouse on Oral Problems 1993).

The extent of gingival banding measured by number

of affected sites has been shown to depend on tobacco

usage (Swango et al. 1991). While 15% of affected sites

were originally reported to bleed on probing and 11%

exhibited spontaneous bleeding (Winkler et al. 1988),

a key feature of linear gingival erythema is now con-

sidered to be lack of bleeding on probing (Robinson et

al. 1994).

Some studies of various groups of HIV-infected

patients have revealed prevalences of gingivitis with

band-shaped patterns in 0.5-49% (Klein et al. 1991,

Swango et al. 1991, Barr et al. 1992, Laskaris et al. 1992,

Masouredis et al. 1992, Riley et al. 1992, Ceballos-Sa-

lobrena et al. 1996, Robinson et al. 1996). These preva

lence values reflect some of the problems with non-

standardized diagnosis and selection of study groups.

A few studies of unbiased groups of patients have

indicated that gingivitis with band-shaped or punc-

tate marginal erythema may be relatively rare in HIV-

infected patients, and probably a clinical finding

which is no more frequent than in the general popu-

lation (Drinkard et al. 1991, Friedman et al. 1991).

It is interesting to note that, whereas there was no

HIV-related preponderance of red banding, diffuse

and punctate erythema was significantly more preva-

lent in HIV-infected than in non-HIV-infected indi-

viduals in a British study (Robinson et al. 1996). Red

gingival banding as a clinical feature alone was, there-

fore, not strongly associated with HIV infection.

There are indications that candidal infection is the

background of some cases of gingival inflammation

including LGE (Winkler et al. 1988, Robinson et al.

1994), but studies have revealed a microflora compris-

ing both C.

albicans,

and a number of periopathogenic

bacteria consistent with those seen in conventional

periodontitis, i.e.

Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella

intermedia, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Fuso-

bacterium nucleatum and

Campylobacter rectus

(Murray

et al. 1988, 1989, 1991). By DNA probe detection, the

percentage of positive sites in HIV associated gingivi-

tis as compared with matched gingivitis sites of HIV

seronegative patients for

A. actinomycetemcomitans

was

23% and 7% respectively, for P. gingivalis 52% and

17%, P. intermedia 63% and 29%, and for C. rectus 50%

and 14% (Murray et al. 1988, 1989, 1991). C.

albicans

has been isolated by culture in about 50% of HIV

associated gingivitis sites, in 26% of unaffected sites

of HIV seropositive patients and in 3% of healthy sites

of HIV seronegative patients. The frequent isolation

and the pathogenic role of C.

albicans

may be related

to the high levels of the yeasts in saliva and oral

mucosa of HIV-infected patients (Tylenda et al. 1989).

An interesting histopathologic study of biopsy

specimens from the banding zone has revealed no

inflammatory infiltrate but an increased number of

blood vessels, which explains the red color of the

lesions (Glick et al. 1990). The incomplete inflamma-

tory reaction of the host tissue may be the background

of the lacking response to conventional treatment.

A number of diseases present clinical features re-

sembling those of LGE and which, accordingly, do not

resolve after improved oral hygiene and debridement.

NON-PLAQUE INDUCED INFLAMMATORY GINGIVAL LESIONS •

2

75

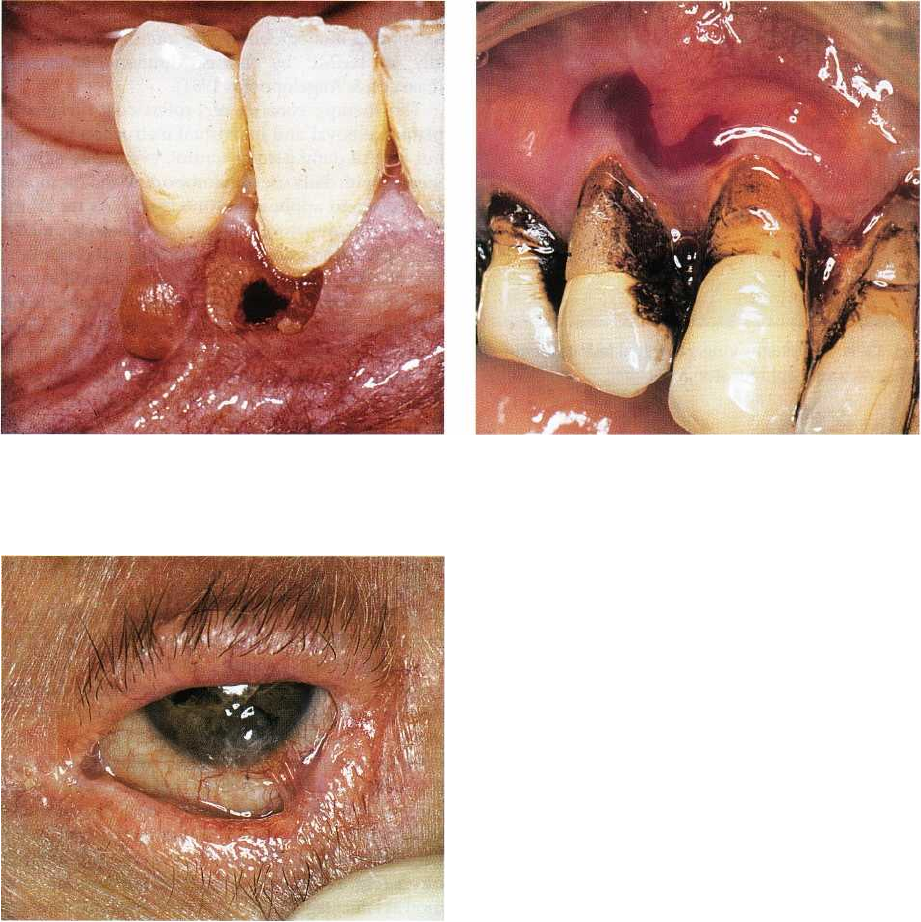

Fig. 12-12. Gingival histoplasmosis with loss of peri

odontal tissue around second premolar.

Fig. 12-13. Same patient as shown in Fig. 12-12. Lin-

gual aspect with ulceration in the deeper part of crater

-formed lesion.

Examples are oral lichen planus, which is frequently

associated with a similar inflammatory red band of

the attached gingiva (Holmstrup et al. 1990) and so is

sometimes mucous membrane pemphigoid (Pind-

borg 1992) or erythematous lesions associated with

renal insufficiency because of the salivary ammonia

production associated with the high levels of urea.

There is little information about treatment based on

controlled studies of this type of affection. Conven-

tional therapy plus rinsing with 0.12% chlorhexidine

gluconate twice daily has shown significant improve-

ment after 3 months (Grassi et al. 1989). It was men-

tioned above that LGE in some cases might be related

to the presence of

Candida

strains. In accordance with

this finding, clinical observations suggest that im-

provement is frequently dependent on successful

eradication of intraoral

Candida

strains, which results

in disappearance of the characteristic features (

Winkler et al. 1988). Consequently, attempts to iden-

tify the presence of fungal infection either by culture

or smear is recommendable followed by antimycotic

therapy in Candida-positive cases.

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is a granulomatous disease caused by

Histoplasma capsulatum,

a soil saprophyte found

mainly in feces from birds and cats. The infection

occurs in the north-eastern, south-eastern, mid Atlan-

tic and central states of the US. It is also found in

Central and South America, India, East Asia and Aus-

tralia. Histoplasmosis is the most frequent systemic

mycosis in the US. Airborne spores from the mycelial

form of the organism mediate it (Rajah & Essa 1993).

In the normal host, the course of the infection is sub-

clinical (Anaissie et al. 1986). The clinical manifesta-

tions include acute and chronic pulmonary histoplas-

mosis and a disseminated form, mainly occurring in

immunocompromised patients (Cobb et al. 1989). Oral

lesions have been seen in 30% of patients with pulmo-

nary histoplasmosis and in 66% of patients with the

disseminated form (Weed & Parkhill 1948, Loh et al.

1989). The oral lesions may affect any area of the oral

mucosa (Chinn et al. 1995) including the gingiva. They

initiate as nodular or papillary and later may become

ulcerative with loss of gingival tissue, and painful (

Figs. 12-12 and 12-13). They are sometimes granu-

lomatous and the clinical appearance may resemble a

malignant tumor (Boutros et al. 1995). The diagnosis

is based on clinical appearance and histopathology

and/or culture, and the treatment consists of systemic

antifungal therapy.

GINGIVAL LESIONS OF GENETIC

ORIGIN

Hereditary gingival fibromatosis

Gingival hyperplasia (synonymous with gingival

overgrowth, gingival fibromatosis) may occur as a

side effect to systemic medications including pheny-

toin, sodium valproate, cyclosporine and dihydro-

pyridines. These lesions are to some extent plaque-de-

pendent and they are reviewed in Chapter 7. Gingival

hyperplasia may also be of genetic origin. Such lesions

are known as hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF),

which is an uncommon condition characterized by

diffuse gingival enlargement, sometimes covering

major parts of, or the total, tooth surfaces. The lesions

develop irrespective of effective plaque removal.

HGF may be an isolated disease entity or part of a

syndrome (Gorlin et al. 1990), associated with other

clinical manifestations, such as hypertrichosis (Horn-

ing et al. 1985, Cuestas-Carneiro & Bornancini 1988),

276 • CHAPTER 12

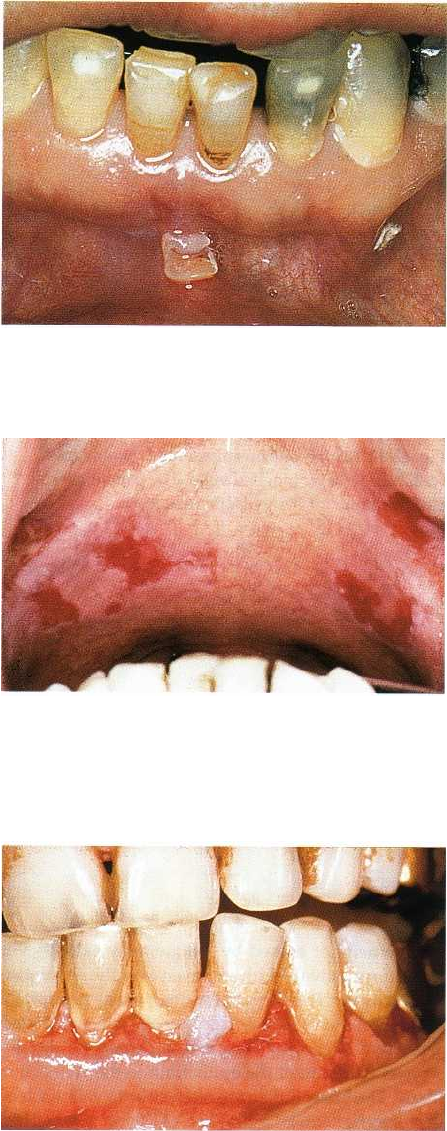

Fig. 12-14. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis. Facial as-

pect with partial coverage of teeth.

Fig. 12-15. Same patient as shown in Fig.12-15. The

maxillary gingival fibromatosis is severe and has re

sulted in total disfiguration of the dental arch.

mental retardation (Araiche & Brode 1959), epilepsy

(Ramon et al. 1967), hearing loss (Hartsfield et al.

1985), growth retardation (Bhowmick et al. 2001) and

abnormalities of extremities (Nevin et al. 1971, Skrin-

jaric & Basic 1989). Most cases are related to an autoso

mal dominant mode of inheritance, but cases have

been described with an autosomal recessive back-

ground (Emerson 1965, Jorgensen & Cocker 1974,

Singer et al. 1993). The most common syndrome of

HGF includes hypertrichosis, epilepsy and mental

retardation; the two latter features, however, are not

present in all cases (Gorlin et al. 1990).

Typically, HGF presents as large masses of firm,

dense, resilient, insensitive fibrous tissue that covers

the alveolar ridges and extends over the teeth result-

ing in extensive pseudopockets. The color may be

normal or erythematous if inflamed (Figs. 12-14 and

12-15). Depending on extension of the gingival en-

largement, patients complain of functional and es-

thetic problems. The enlargement may result in pro-

trusion of the lips, and they may chew on a consider-

able hyperplasia of tissue covering the teeth. HGF is

seldom present at birth but may be noted at an early

age. If the enlargement is present before tooth erup-

tion, the dense fibrous tissue may interfere with or

prevent the eruption (Shafer et al. 1983).

Studies have suggested that an important patho-

genic mechanism may be enhanced production of

transforming growth factor (TGF-beta 1) reducing the

proteolytic activities of HGF fibroblasts, which again

favor the accumulation of extracellular matrix (Colet-

ta et al. 1999). Recently a locus for autosomal domi-

nant HGF has been mapped to a region on chromo-

some 2 (Hart et al. 1998, Xiao et al. 2000), although at

least two genetically distinct loci seem to be responsi-

ble for this type of HGF (Hart et al. 2000).

The histological features of HGF include moderate

hyperplasia of a slightly hyperkeratotic epithelium

with extended rete pegs. The underlying stroma is

almost entirely made up of dense collagen bundles

with only few fibroblasts. Local accumulation of in-

flammatory cells may be present (Shafer et al. 1983).

Histological examination may facilitate the differen-

tial diagnosis from other genetically determined gin-

gival enlargements such as Fabry disease, charac-

terized by telangiectasia.

The treatment is surgical removal, often in a series

of gingivectomies, but relapses are not uncommon. If

the volume of the overgrowth is extensive, a reposi-

tioned flap to avoid exposure of connective tissue by

gingivectomy may better achieve elimination of

pseudopockets.

NON-PLAQUE INDUCED INFLAMMATORY GINGIVAL LESIONS • 277

GINGIVAL DISEASES OF

SYSTEMIC ORIGIN

Mucocutaneous disorders

A variety of mucocutaneous disorders present gingi-

val manifestations sometimes in the form of

desquamative lesions or ulceration of the gingiva. The

most important of these diseases are lichen planus,

pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, erythema multi-

forme and lupus erythematosus.

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is the most common mucocutaneous

disease manifesting on the gingiva. The disease may

affect skin and oral as well as other mucosal mem-

branes in some patients while others may present

either skin or oral mucosal involvement alone. Oral

involvement alone is common and concomitant skin

lesions in patients with oral lesions have been found

in 5-44% of the cases (Andreasen 1968, Axel &

Rundquist 1987). The disease may be associated with

severe discomfort and since it has been shown to

possess a premalignant potential, although this is still a

controversial issue (Holmstrup 1992), it is important to

diagnose and treat the patients and to follow them at

the regular oral examinations (Holmstrup et al. 1988).

The prevalence of oral lichen planus (OLP) in

various populations has been found to be 0.1-4% (

Scully et al. 1998a). The disease may afflict patients at

any age although it is seldom observed in childhood (

Scully et al. 1994).

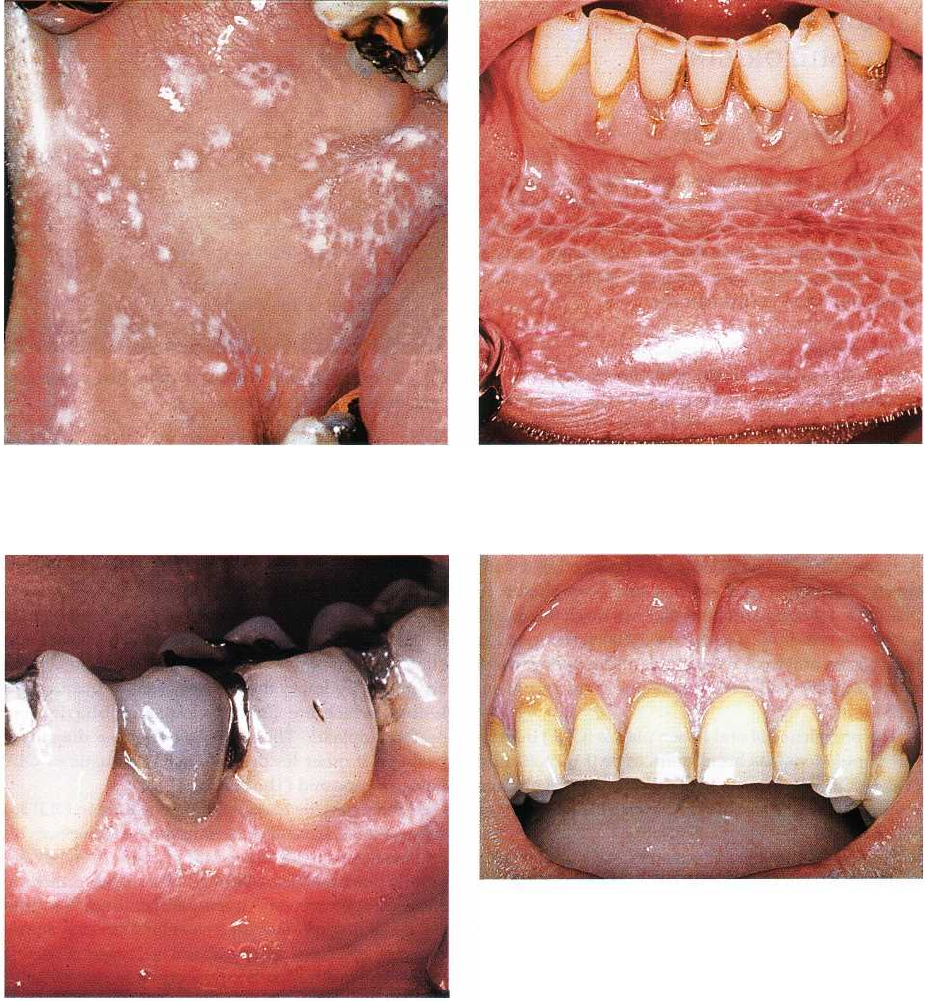

Skin lesions are characterized by red papules with

white striae (Wickham striae) (Fig. 12-16). Itching is a

common symptom, and the most frequent locations

are the flexor aspects of the arms, the thighs and the

neck. In the vast majority of cases the skin lesions

disappear spontaneously after a few months, which is

in sharp contrast with the oral lesions, which usually

remain for years (Thorn et al. 1988).

A variety of clinical appearances is characteristic of

OLP. These include:

• papular (Fig. 12-17)

• reticular (Figs. 12-18 and 12-19)

• plaque-like (Fig. 12-20)

• atrophic (Figs. 12-21 to 12-25)

• ulcerative (Figs. 12-22 and 12-27)

• bullous (Fig. 12-29)

Simultaneous presence of more than one type of lesion

is common (Thorn et al. 1988). The most characteristic

clinical manifestations of the disease and the basis of

the clinical diagnosis are white papules (Fig. 12-17)

and white striations (Figs. 12-18, 12-19, 12-26 and

12-27), which often form reticular patterns (Thorn et

al. 1988). Sometimes atrophic and ulcerative lesions

Fig. 12-16. Skin lesions of lichen planus. Red papules

with delicate white striations.

are referred to as erosive (Rees 1989). Papular, reticular

and plaque-type lesions usually do not give rise to

significant symptoms, whereas atrophic and ulcera-

tive lesions are associated with moderate to severe

pain, especially in relation to oral hygiene procedures

and eating. OLP frequently persists for many years (

Thorn et al. 1988). Any area of the oral mucosa may

be affected by OLP, but the lesions often change in

clinical type and extension over the years. Such

changes may imply the development of plaque-type

lesions, which are clinically indistinguishable from

oral leukoplakia. This may give rise to a diagnostic

problem if other lesions more characteristic of OLP

have disappeared (Thorn et al. 1988).

A characteristic histopathologic feature in OLP is a

subepithelial, band-like accumulation of lymphocytes

and macrophages characteristic of a type IV hypersen-

sitivity reaction (Eversole et al. 1994). The epithelium

shows hyperortho- or hyperparakeratinization and

basal cell disruption with transmigration of lympho-

cytes into the basal and parabasal cell layers (Eversole

1995). The infiltrating lymphocytes have been identi-

fied as CD4+ and CDS+ positive cells (Buechner 1984,

Walsh et al. 1990, Eversole et al. 1994). Other charac-

teristic features are Civatte bodies, which are dyskera-

totic basal cells. Common immunohistochemical find-

ings of OLP-lesions are fibrin in the basement mem-

brane zone, but deposits of IgM, C3, C4, and C5 may

also be found. None of these findings are specific of

OLP (Schie dt et al. 1981, Kilpi et al. 1988, Eversole et

al. 1994).

The subepithelial inflammatory reaction in OLP

lesions is presumably due to a so far unidentified

antigen in the junctional zone between epithelium and

connective tissue or to components of basal epithelial

cells (Holmstrup & Dabelsteen 1979, Walsh et al. 1990,

Sugerman et al. 1994). A lichen planus specific antigen

in the stratum spinosum of skin lesions has been

described (Camisa et al. 1986), but this antigen does

not appear to play a significant role in oral lesions

since it is rarely identified there. It is still an open

278 • CHAPTER 12

Fig. 12-17. Oral lichen planus. Papular lesion of right

buccal mucosa.

Fig. 12-18. Oral lichen planus. Reticular lesion of lower

lip mucosa. The white striations are denoted Wickham

striae.

Fig. 12-19. Oral lichen planus. Reticular lesions of

gingiva in lower left premolar and molar region.

question whether OLP is a multivariate group of eti-

ologically diverse diseases with common clinical and

histopathological features or a disease entity charac-

terized by a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to an

antigen in the basement membrane area. The clinical

diagnosis is based on the presence of papular or re-

ticular lesions. The diagnosis may be supported by

histopathological findings of hyperkeratosis, degen-

erative changes of basal cells and subepithelial inflam-

mation dominated by lymphocytes and macrophages (

Holmstrup 1999).

The uncertain background of OLP results in several

border zone cases of so-called oral lichenoid lesions (

OLL) for which a final diagnosis is difficult to establ-

ish. The most common OLLs are probably lesions in

Fig. 12-20. Oral lichen planus. Plaque-type lesion of

maxillary gingiva.

contact with dental restorations (Holmstrup 1991) (

see later in this chapter). Other types of OLL are

associated with various types of medications

including antimalarials, quinine, quinidine, non-

steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, thiazides,

diuretics, gold salts, penicillamine, beta-blockers and

others (Scully et al. 1998a). Graft-versus-host

reactions are also characterized by a lichenoid

appearance (Fujii et a1.1988) and a group of OLL is

associated with systemic diseases of which liver

disease has been revealed lately (Fortune & Buchanan

1993, Bagan et al. 1994, Carrozzo et al. 1996). This

appears to be particularly evident in South-ern Europe

and Japan where hepatitis C has been found in 20-

60% of OLL cases (Bagan et al. 1994, Gandolfo et

al. 1994, Nagao et al. 1995).

Several follow-up studies have demonstrated that

OLP is associated with increased development of oral

cancer, the frequency of cancer development being in

the range of 0.5-2% (Holmstrup et al. 1988).

NON-PLAQUE INDUCED INFLAMMATORY GINGIVAL LESIONS • 279

Fig. 12-21. Oral lichen planus. Atrophic lesions of facial

maxillary and mandibular gingiva. Such lesions were

previously often termed desquamative gingivitis.

Fig. 12-22. Oral lichen planus. Atrophic and ulcerative

lesion of maxillary gingiva. Note that the margin of the

gingiva has normal color in upper incisor region,

which distinguishes the lesions from plaque induced

gingivitis.

Fig. 12-23. Oral lichen planus. Atrophic and reticular le-

sion of maxillary gingiva. Several types of lesions are

often present simultaneously.

Fig. 12-24. Oral lichen planus. Atrophic and reticular le-

sion of lower left canine region. Plaque accumulation

results in exacerbation of oral lichen planus, and atro-

phic lesions compromises oral hygiene procedures. This

may lead to a vicious circle that the dentist can help in

breaking.

Fig. 12-25. Oral lichen planus. Atrophic and reticular le-

sion of right maxillary gingiva in a patient using an

electric toothbrush, which is traumatic to the marginal

gingiva. The physical trauma results in exacerbation of

the lesion with atrophic characteristics and pain.

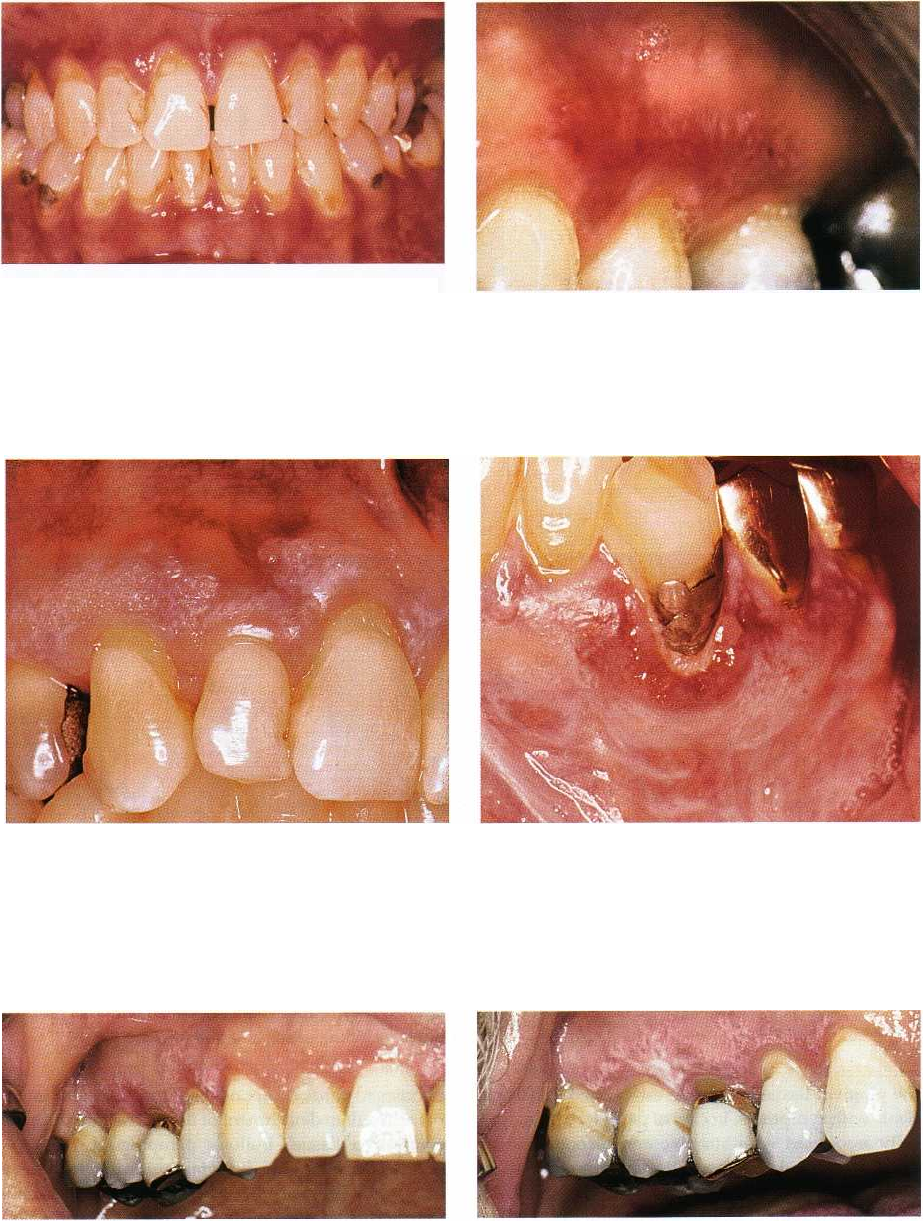

The most important part of the therapeutic regimen is

an atraumatic meticulous plaque control, which results

in significant improvement in many patients

Fig. 12-26. Same patient as shown in Fig. 12-25 after

modified toothbrushing procedure with no traumatic

action on marginal gingiva.

(Holmstrup et al. 1990) (Figs. 12-25 to 12-28). Individ-

ual oral hygiene procedures with the purpose of effec-

tive plaque removal without traumatic influence on

280 • CHAPTER 12

Fig. 12-27. Oral lichen planus. Atrophic and ulcera-

tive/reticular lesions of maxillary and mandibular inci-

sor region. The patient, who is a 48-year-old woman,

suffers from severe discomfort from food, beverages

and toothbrushing.

Fig. 12-28. Same patient as shown in Fig. 12-27 after

periodontal treatment and extraction of teeth with

deep pockets. An individual oral hygiene program,

which ensured gentle, meticulous plaque removal has

been used by the patient for three months. The atro-

phic/ulcerative lesions are now healed and no more

symptoms left.

Fig. 12-29. Oral lichen planus. Bullous/reticular lesion

of left palatal ucosa.

the gingival tissue should be established for all pa-

tients with symptoms. In case of persistent pain, typi-

cally associated with atrophic and ulcerative affec-

tions, antifungal treatment may be necessary if the

affections are hosting yeast, which occurs in 37% of

OLP-cases (Krogh et al. 1987). In painful cases, which

have not responded to the treatment above, topical

corticosteroids, preferably in a paste or an ointment,

should be used three times daily for a number of

weeks. However, in such cases relapses are very com-

mon, which is why intermittent periods of treatment

may be needed over an extended period of time.

Pemphigoid

Pemphigoid is a group of disorders in which autoan-

Fig. 12-30. Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid af-

fecting the attached gingiva of both jaws. The lesions

are erythematous and resemble atrophic lichen planus

lesions. They result in pain associated with oral proce

dures including eating and oral hygiene.

tibodies towards components of the basement mem-

brane result in detachment of the epithelium from the

connective tissue. Bullous pemphigoid predominantly

affects the skin, but oral mucosal involvement may

occur (Brooke 1973, Hodge et al. 1981). If only

mucous membranes are affected, the term benign mu-

cous membrane pemphigoid (BMMP) is often used.

The term cicatricial pemphigoid is also used to de-

scribe subepithelial bullous disease limited to the

mouth or eyes and infrequently other mucosal areas.

This term is problematic, because usually oral lesions

do not result in scarring, whereas this is an important

danger for ocular lesions (Scully et al. 1998b). It is now

evident that BMMP comprises a group of disease

entities characterized by an immune reaction involv-

NON-PLAQUE INDUCED INFLAMMATORY GINGIVAL LESIONS • 281

Fig. 12-31. Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid

with intact and ruptured gingival bulla.

Fig. 12-32. Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid

with hemorrhagic gingival bulla. The patient uses

chlorhexidine for daily plaque reduction.

Fig. 12-33. Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid.

Eye lesion with scar formation due to coalescence of

palpebral and conjunctival mucosa.

ing autoantibodies directed against various basement

membrane zone antigens (Scully & Laskaris 1998).

These antigens have been identified as hemides-

mosome or lamina lucida components (Leonard et al.

1982, 1984, Manton & Scully 1988, Domloge-Hultsch

et al. 1992, 1994). In addition, complement-mediated

cell destructive processes may be involved in the

pathogenesis of the disease (Eversole 1994). The trig-

ger mechanisms behind these reactions, however,

have not yet been revealed.

The majority of affected patients are females with a

mean age at onset of 50 years or over (Shklar &

McCarthy 1971). Oral involvement in BMMP is almost

inevitable and usually the oral cavity is the first site of

disease activity (Silverman et al. 1986, Gallagher &

Shklar 1987). Any area of the oral mucosa may be

involved in BMMP, but the main manifestation is

desquamative lesions of the gingiva presenting in-

tensely erythematous attached gingival (Laskaris et

al. 1982, Silverman et al. 1986, Gallagher & Shklar

1987) (Fig. 12-30). The inflammatory changes, as al-

ways when not caused by plaque, may extend over

the entire gingival width and even over the muco-gin-

gival junction. Rubbing of the gingiva may precipitate

bulla formation (Dahl & Cook 1979). This is denoted a

positive Nicholsky sign and is caused by the de-

stroyed adhesion of the epithelium to the connective

tissue. The intact bullae are often clear to yellowish or

they may be hemorrhagic (Figs. 12-31 and 12-32). This,

again, is due to the separation of epithelium from

connective tissue at the junction resulting in exposed

vessels inside the bullae. Usually, the bullae rupture

rapidly leaving fibrin coated ulcers. Sometimes, tags

of loose epithelium can be found due to rupture of

bullae. Other mucosal surfaces may be involved in

some patients. Ocular lesions are particularly impor-

tant because scar formation can result in blindness (

Williams et al. 1984) (Fig. 12-33).

The separation of epithelium from connective tis-

sue at the basement membrane area is the main diag-

nostic feature of BMMP. An unspecific inflammatory

reaction is a secondary histologic finding. In addition,

282 • CHAPTER 12

Fig. 12-34. Pemphigus vulgaris. Initial lesion resem-

bling recurrent aphtous stomatitis.

Fig. 12-35. Pemphigus vulgaris. Erosions of soft palatal

mucosa. The erosive lesions are due to loss of the super

ficial part of the epithelium, leaving the connective tis-

sue covered only by the basal cell layers.

Fig. 12-36. Pemphigus vulgaris. Erosive lesions of the

attached gingiva.

immunohistochemical examination can help distin-

guish BMMP from other vesiculobullous diseases, in

particular pemphigus which is life threatening. De-

posits of C3, IgG, and sometimes other immunoglobu-

lins as well as fibrin are found at the basement mem-

brane zone in the vast majority of cases (Laskaris &

Nicolis 1980, Daniels & Quadra-White 1981, Manton &

Scully 1988). It is important to involve peri-lesional

tissue in the biopsy because the characteristic features

may be lost within lesional tissue (Ullman 1988). Cir-

culating immunoglobulins are found only occasion-

ally in BMMP by indirect immunofluorescence (

Laskaris Sr Angelopoulos 1981).

The therapy consists of professional atraumatic

plaque removal and individual instruction in gentle

but careful daily plaque control, eventually supple-

mented with daily use of chlorhexidine and / or topical

corticosteroid application if necessary. As for all the

chronic inflammatory oral mucosal diseases, oral hy-

giene procedures are very important and controlling

the infection from plaque bacteria may result in con-

siderable reduction of disease activity and symptoms.

However, the disease is chronic in nature and forma-

tion of new bullae is inevitable in most patients. Topi-

cal corticosteroids, preferably applied as a paste at

night, temper the inflammatory reaction.

Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus is a group of autoimmune diseases char-

acterized by formation of intraepithelial bullae in skin

and mucous membranes. The group comprises sev-

eral variants, pemphigus vulgaris (PV) being the most

common and most serious form (Barth & Yenning

1987).

Individuals of Jewish or Mediterranean back-

ground are more often affected by PV than others. This

is an indication of a strong genetic background of the

disease (Pisanti et al. 1974). The disease may occur at

any age, but is typically seen in the middle-aged or

elderly. It presents with widespread bulla formation

often including large areas of skin, and if left untreated

the disease is life threatening. Intraoral onset of the

disease with bulla formation is very common and

lesions of the oral mucosa including the gingiva are

frequently seen. Early lesions may resemble aphtous

ulcers (Fig. 12-34), but widespread erosions are com-

mon at later stages (Fig. 12-35). Gingival involvement

may present as painful desquamative lesions or as

erosions or ulcerations, which are remains of ruptured

bullae (Fig. 12-36). Such lesions may be indistinguish-

able from BMMP (Zegarelli & Zegarelli 1977, Sciubba

1996). Since the bulla formation is located in the spi-

nous cell layer, the chance of seeing an intact bulla is

even more reduced than in BMMP. Involvement of

other mucous membranes is common (Laskaris et al.

1982). The ulcers heal slowly, usually without scar

formation, and the disease runs a chronic course with

recurring bulla formation (Zegarelli & Zegarelli 1977).

The diagnosis is based on the characteristic histo-

logical feature of PV that is intraepithelial bulla for-

mation due to destruction of desmosomes resulting in

acantholysis. The bullae contain non-adhering free

epithelial cells, denoted Tzank cells, which have lost

their intercellular bridges (Coscia-Porrazzi et al. 1985,

Nishikawa et al. 1996). Mononuclear cells and neutro-

phils dominate the associated inflammatory reaction.

Immunohistochemistry reveals pericellular epithelial

deposits of IgG and C3. Circulating autoantibodies

against interepithelial adhesion molecules are detect-