Hugo W.B., Russel A.D.(ed). Pharmaceutical Microbiology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

peak incidence between 5 and 15 years of age, while pneumococcal meningitis is

predominantly a disease of adults.

Penicillin is the drug of choice for the treatment of group B streptococcal, meningo-

coccal and pneumococcal infections but, as discussed earlier, CSF concentrations of

penicillin are significantly influenced by the intensity of the inflammatory response.

To achieve therapeutic concentrations within the CSF, high dosages are required, and

in the case of pneumococcal meningitis should be continued for 10-14 days.

Resistance of H. influenzae to ampicillin has increased in the past decade and varies

geographically. Thus, it can no longer be prescribed with confidence as initial therapy,

and cetotaxime or ceftriaxone are the preferred alternatives. However, once laboratory

evidence for /3-lactamase activity is excluded, ampicillin can be safely substituted.

Escherichia coli meningitis carries a mortality of greater than 40% and reflects

both the virulence of this organism and the pharmacokinetic problems of achieving

adequate CSF antibiotic levels.The broad-spectrum cephalosporins such as cefotaxime,

ceftriaxone or ceftazidime have been shown to achieve satisfactory therapeutic levels

and are the agents of choice to treat Gram-negative bacillary meningitis. Treatment

again must be prolonged for periods ranging from 2 to 4 weeks.

Brain abscess presents a different therapeutic challenge. An abscess is locally

destructive to the brain and causes further damage by increasing intracranial pressure.

The infecting organisms are varied but those arising from middle ear or nasal sinus

infection are often polymicrobial and include anaerobic bacteria, microaerophilic species

and Gram-negative enteric bacilli. Less commonly, a pure Staph, aureus abscess may

complicate blood-borne spread. Brain abscess is a neurosurgical emergency and requires

drainage. However, antibiotics are an important adjunct to treatment. The polymicrobial

nature of many infections demands prompt and careful laboratory examination to

determine optimum therapy. Drugs are selected not only on their ability to penetrate

the blood-brain barrier and enter the CSF but also on their ability to penetrate the brain

substance. Metronidazole has proved a valuable alternative agent in such infections,

although it is not active against microaerophilic streptococci which must be treated with

high-dose benzylpenicillin. The two are often used in combination. Chloramphenicol

is an alternative agent.

Antibiotic policies

Rationale

The plethora of available antimicrobial agents presents both an increasing problem of

selection to the prescriber and difficulties to the diagnostic laboratory as to which agents

should be tested for susceptibility. Differences in antimicrobial activity among related

compounds are often of minor importance but can occasionally be of greater significance

and may be a source of confusion to the non-specialist. This applies particularly to

large classes of drugs, such as the penicillins and cephalosporins, where there has been

an explosion in the availability of new agents in recent years. Guidance, in the form of

an antibiotic policy, has a major role to play in providing the prescriber with a range of

agents appropriate to his/her needs and should be supported by laboratory evidence of

susceptibility to these agents.

Clinical uses of antimicrobial drugs 145

In recent years, increased awareness of the cost of medical care has led to a major

review of various aspects of health costs. The pharmacy budget has often attracted

attention since, unlike many other hospital expenses, it is readily identifiable in terms

of cost and prescriber. Thus, an antibiotic policy is also seen as a means whereby the

economic burden of drug prescribing can be reduced or contained. There can be little

argument with the recommendation that the cheaper of two compounds should be

selected where agents are similar in terms of efficacy and adverse reactions. Likewise,

generic substitution is also desirable provided there is bioequivalence. It has become

increasingly impractical for pharmacists to stock all the formulations of every antibiotic

currently available, and here again an antibiotic policy can produce significant savings

by limiting the amount of stock held. A policy based on a restricted number of agents

also enables price reduction on purchasing costs through competitive tendering. The

above activities have had a major influence on containing or reducing drug costs,

although these savings have often been lost as new and often expensive preparations

become available, particularly in the field of biological and anticancer therapy.

Another argument in favour of an antibiotic policy is the occurrence of drug-resistant

bacteria within an institution. The presence of sick patients and the opportunities for

the spread of microorganisms can produce outbreaks of hospital infection. The excessive

use of selected agents has been associated with the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria

which have often caused serious problems within high-dependency areas, such as

intensive care units or burns units where antibiotic use is often high. One oft-quoted

example is the occurrence of a multiple-antibiotic resistant K. aerogenes within a

neurosurgical intensive care unit in which the organism became resistant to all currently

available antibiotics and was associated with the widespread use of ampicillin. By

prohibiting the use of all antibiotics, and in particular ampicillin, the resistant organism

rapidly disappeared and the problem was resolved.

In formulating an antibiotic policy, it is important that the susceptibility of

microorganisms be monitored and reviewed at regular intervals. This applies not

only to the hospital as a whole, but to specific high-dependency units in particular.

Likewise general practitioner samples should also be monitored. This will provide

accurate information on drag susceptibility to guide the prescriber as to the most effective

agent.

4.2 Types of antibiotic policies

There are a number of different approaches to the organization of an antibiotic policy.

These range from a deliberate absence of any restriction on prescribing to a strict policy

whereby all anti-infective agents must have expert approval before they are administered.

Restrictive policies vary according to whether they are mainly laboratory controlled,

by employing restrictive reporting, or whether they are mainly pharmacy controlled,

by restrictive dispensing. In many institutions it is common practice to combine the

two approaches.

Free prescribing policy

The advocates of a free prescribing policy argue that strict antibiotic policies are both

4.2.1

146 Chapter 6

impractical and limit clinical freedom to prescribe. It is also argued that the greater the

number of agents in use the less likely it is that drug resistance will emerge to any one

agent or class of agents. However, few would support such an approach, which is

generally an argument for mayhem.

4.2.2 Restricted reporting

Another approach that is widely practised in the UK is that of restricted reporting. The

laboratory, largely for practical reasons, tests only a limited range of agents against

bacterial isolates. The agents may be selected primarily by microbiological staff or

following consultation with their clinical colleagues. The antibiotics tested will vary

according to the site of infection, since drugs used to treat urinary tract infections often

differ from those used to treat systemic disease.

There are specific problems regarding the testing of certain agents such as the

cephalosporins where the many different preparations have varying activity against

bacteria. The practice of testing a single agent to represent first generation, second

generation or third generation compounds is questionable, and with the new compounds

susceptibility should be tested specifically to that agent. By selecting a limited range of

compounds for use, sensitivity testing becomes a practical consideration and allows

the clinician to use such agents with greater confidence.

4.2.3 Restricted dispensing

As mentioned above, the most Draconian of all antibiotic policies is the absolute

restriction of drug dispensing pending expert approval. The expert opinion may be

provided by either a microbiologist or infectious disease specialist. Such a system can

only be effective in large institutions where staff are available 24 hours a day. This

approach is often cumbersome, generates hostility and does not necessarily create the

best educational forum for learning effective antibiotic prescribing.

A more widely used approach is to divide agents into those approved for unrestricted

use and those for restricted use. Agents on the unrestricted list are appropriate for

the majority of common clinical situations. The restricted list may include agents

where microbiological sensitivity information is essential, such as for vancomycin

and certain aminoglycosides. In addition, agents which are used infrequently but for

specific indications, such as parenteral amphotericin B, are also restricted in use. Other

compounds which may be expensive and used for specific indications, such as broad-

spectrum /Mactams in the treatment of Ps. aeruginosa infections, may also be justifiably

included on the restricted list. Items omitted from the restricted or unrestricted list are

generally not stocked, although they can be obtained at short notice as necessary.

Such a policy should have a mechanism whereby desirable new agents are added

as they become available and is most appropriately decided at a therapeutics com-

mittee. Policing such a policy is best effected as a joint arrangement between senior

pharmacists and microbiologists. This combined approach of both restricted reporting

and restricted prescribing is extremely effective and provides a powerful educational

tool for medical staff and students faced with learning the complexities of modern

antibiotic prescribing.

Clinical uses of antimicrobial drugs 147

5 Further reading

Finch R.G. (1996) Antibacterial chemotherapy: principles of use. Medicine, 24, 24-26.

Greenwood D. (1995) Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lambert H.P., O'Grady F., Greenwood D. & Finch R.G. (1996) Antibiotic and Chemotherapy, 7th edn.

Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Mandell G.L., Douglas R.G. & Bennett J.E. (eds) (1995) Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases,

4th edn. New York: John Wiley.

148 Chapter 6

Manufacture of antibiotics

Introduction

Industrial scale manufacture of the majority of antibiotics is fermentation-based.

Strictly speaking, fermentations are biological processes occurring in the absence of

air (oxygen). However, the term is now commonly applied to any large-scale cultivation

of microorganisms, whether aerobic (with oxygen) or anaerobic (without oxygen).

Despite the ever-increasing use of complex instrumentation, the application of

feedback control techniques and the use of computers, the science of antibiotic

fermentation is still imperfectly developed. This technology is involved with a living

cell population which is changing both quantitatively and qualitively throughout the

production cycle: optimization is difficult, because no two ostensibly 'identical' batches

are ever wholly alike. Dealing with the challenge of this variation is one of the attractions

for those who practise in this field.

Choice of examples

The manufacture of benzylpenicillin (penicillin G, originally just 'penicillin') is chosen

as a model for the antibiotic production process. It is the most renowned of antibiotics

and is the first to have been manufactured in bulk. It is still universally prescribed and

is also in demand as input material for semisynthetic antibiotics (Chapter 5).

Developments associated with the penicillin fermentation process have been a significant

factor in the development of modern biotechnology. It was a further 30 years, i.e. not

until the 1970s, before there were significant new advances in industrial fermentations.

No single product can exemplify all the important features of antibiotic manufacture.

Benzylpenicillin is a /^-lactam. Brief accounts are given of the manufacture of two

other /3-lactams, penicillin V (phenoxymethylpenicillin) and cephalosporin C, to

illustrate further key points.

Manufacture of antibiotics 149

1 Introduction 3.4.1 Batched medium

3.4.2 Fed nutrients

2 Choice of examples 3.4.3 Stimulation by PAA

3.4.4 Termination

3 The production of benzylpenicillin 3.5 Extraction

3.1 The organism 3.5.1 Removal of cells

3.2 Inoculum preparation 3.5.2 Isolation of benzylpenicillin

3.3 Thefermenter 3.5.3 Treatment of crude extract

3.3.1 Oxygen supply

3.3.2 Temperature control 4 The production of penicillin V

3.3.3 Defoaming agents and instrumentation

3.3.4 Media additions 5 The production of cephalosporin C

3.3.5 Transfer and sampling systems

3.4 Control of the fermentation 6 Further reading

7

However, important as the /3-lactams are, they are but one of many families of

antibiotics (Chapter 5). Furthermore, most industrial microorganisms used to make j8-

lactams are fungi; this is atypical of antibiotics as a whole where bacteria, particularly

Streptomyces spp., predominate. Chapter 5 and some of the further reading at the end

of this chapter provide the broad perspective, including information on those antibiotics

made by total or partial chemical synthesis, against which this present account with its

necessarily selective subject matter should be read.

All the examples are of 'batched' fermentations, i.e. of processes where sterile

medium in a vessel is inoculated, the broth fermented for a defined period (usually

hours or days), the tank emptied and the proceeds extracted ('downstream processing')

to yield the antibiotic. During the fermentation, nutrients, antifoam agents and air

are supplied, the pH is controlled and exhaust gases removed. After emptying the

tank is turned around, that is cleaned and prepared for a new batch. In 'continuous'

fermentations, sterile medium is added to the fermentation with a balancing withdrawal

of broth for product extraction. This has a number of advantages providing the system

can be run clean, i.e. without contamination. One is long fermentation runs of many

weeks, hence greater productivity per vessel due to fewer turnrounds. In continuous

culture the growth rate can be held at an optimum value for product fermentation. It is

therefore suitable for products whose synthesis is proportional to cell density, but is

not generally an economical process for antibiotic production where synthesis is not

associated with growth and there are additional concerns about strain degeneration.

In this chapter there is little discussion of downstream processing operations after

the fermentation stage, i.e. the recovery, purification, quality testing and sterile packaging

of the products, even though these usually account for most of the total manufacturing

costs. The limited discussion is because, beyond the basic principles, there is no simple

model that can be used to illustrate downstream processing, no two processes are

alike and different manufacturers are likely to employ different methods for the same

product. The quality of the fermented material can markedly affect the efficiency of

all the succeeding operations, for at the end of a typical fermentation, the antibiotic

concentration will rarely exceed 20gH and may be as low as 0.5 gH.

Details of the manufacture of streptomycin and griseofulvin are to be found in

previous editions of this book.

3 The production of benzylpenicillin

3.1 The organism

The original organism for the production of penicillin, Penicillium notatum, was isolated

by Fleming in 1926 as a chance contaminant. In 1940, Florey and Chain produced

purified penicillin and its tremendous curative potential became apparent. However,

the liquid surface culture techniques necessary for the cultivation of this obligate aerobe

were lengthy, labour-intensive and prone to contamination. The isolation of a higher-

yielding organism, P. chrysogenum, from an infected Cantaloupe melon obtained in a

market in Peoria, Illinois, USA, was the key advance. This organism could be grown in

deep fermentations in sealed tanks under stirred and aerated conditions, in vessels as

large as 250 m

3

.

150 Chapter 7

From this one ancestral fungus each penicillin manufacturer has evolved a particular

production strain by a series of mutagenic treatments, each followed by the selection

of improved variants. These selected variants have proved capable of producing amounts

of penicillin far greater than those produced by the 'wild' strain, especially when

fermented on media under particular control conditions developed in parallel with the

strains. These strain selection procedures have become a fundamental feature of

industrial biotechnology.

Production strains are stored in a dormant form by any of the standard culture

preservation techniques. Thus, a spore suspension may be mixed with a sterile, finely

divided, inert support and desiccated. Alternatively, spore suspensions in appropriate

media can be lyophilized or stored in a liquid culture biostat.

All laboratory operations are carried out in laminar flow cabinets in rooms in

which filtered air is maintained at a slight positive pressure relative to their outer

environment. Operators wear sterilized clothing and work aseptically. Antibiotic

fermentations are, of strict necessity, pure culture aseptic processes, without con-

taminating organisms.

3.2 Inoculum preparation

The aim is to develop for the production stage fermenter a pure inoculum in sufficient

volume and in the fast-growing (logarithmic) phase so that a high population density is

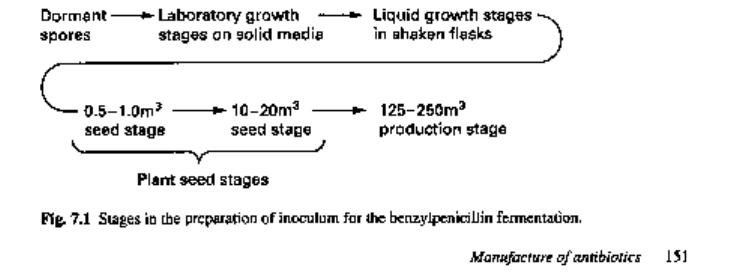

soon obtained. Figure 7.1 shows a typical route by which the inoculum is produced.

The time taken for each seed stage is measured in days and decreases as the sequence

progresses. The final inoculum to the production stage is generally 1-10% of the total

volume of the fementer. If the fermenter is under-inoculated there may be an extended

lag before growth starts and the fermentation period will be prolonged. This is both

uneconomic and may result in degenerative growth which affects performance, quality

and hence also cost.

The inoculum stage media are designed to provide the organism with all the

nutrients that it requires. Adequate oxygen is provided in the form of sterile air and the

temperature is controlled at the desired level. Principal criteria for transfer to the next

stage in the progression are freedom from contamination and growth to a pre-determined

cell density.

Typical of fungi, the organism grows as branching filaments (hyphae) and by the

time that the culture has progressed to the production stage it has a soup-like consistency.

3.3

The fermenter

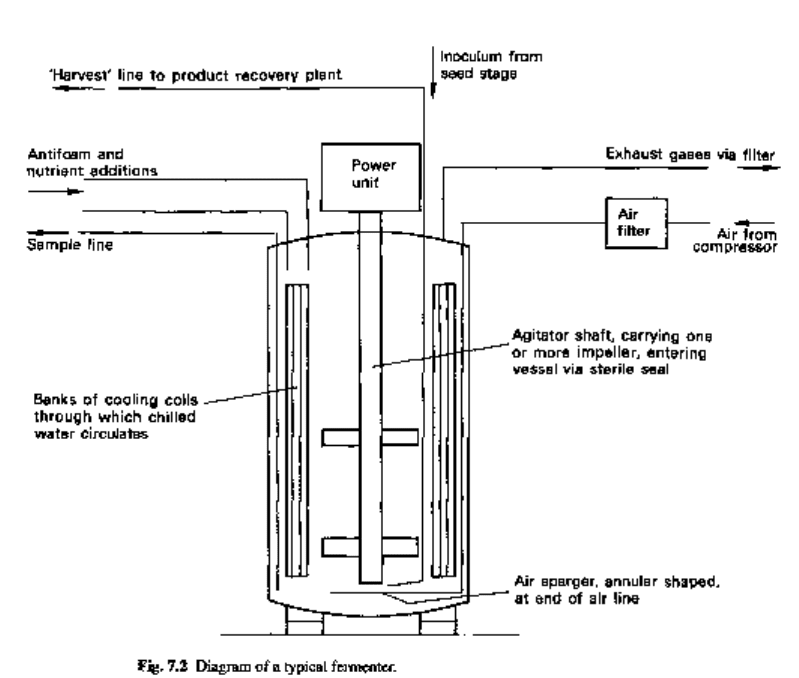

A typical fermenter is a closed, vertical, cylindrical, stainless steel vessel with convexly

dished ends and of 25-250 m

3

capacity. Its height is usually two to three times its

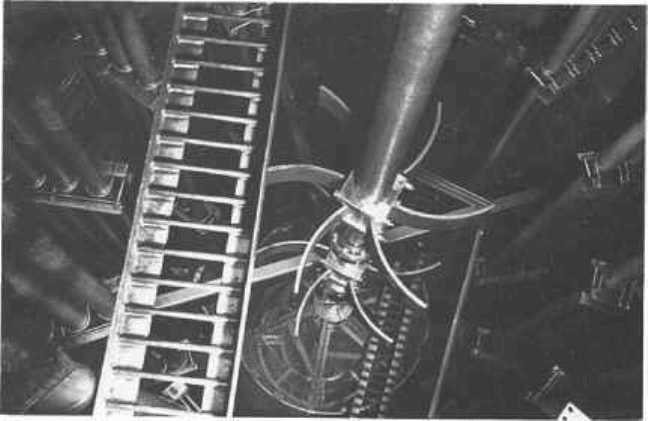

diameter. Figure 7.2 shows such a vessel diagramatically, and Fig. 7.3 gives a view

inside an actual vessel.

3.3.1

Oxygen supply

The penicillin fermentation needs oxygen, which is supplied as filter-sterilized air from

a compressor. Oxygen is critical to aerobic processes and its supply is a crucial aspect

of fementer design and batch control. As oxygen is poorly soluble in water, steps are

taken to assist its passage into the liquid phase and from aqueous solution into the

microorganism. In a conventional fermentation, air is introduced into the bottom of the

vessel via a ring 'sparger' with multiple small holes rather than through a single large

orifice. This breaks the air flow into smaller bubbles which have a greater surface area

to volume ratio and hence greater oxygen transfer. These bubbles lose oxygen as they

rise up the tank and, at the same time, carbon dioxide diffuses into them. The vessel is

kept under a positive head pressure which promotes the dissolution of oxygen and in

152 Chapter 7

Fig. 7.3 View looking down into a 125 m

3

stainless steel fermenter. (Courtesy of Glaxo Wellcome

Operations.)

addition reduces the chances of contamination. The transfer of oxygen is further assisted

by impellers mounted on a rotating vertical shaft driven by a powerful electric motor.

Baffles are also included to achieve the correct blend of shear and of bulk circulation

from the power supplied, and generally to promote intimate contact of cells and nutrients.

Aeration is a major expense as very large amounts of energy are consumed. The design,

size and number of impellers relative to the fermenter design and type of microorganism

form a science in their own right. There has been considerable research into novel,

energetically more efficient methods of aeration, and the next generation of fermenters

may include some that are radically different in design.

3.3.2 Temperature control

The production of benzylpenicillin is very sensitive to temperature. A lot of metabolic

heat is generated and the fermentation temperature has to be reduced by controlled

cooling. This heat transfer is achieved by circulating chilled water through banks of

pipes inside the vessel (which also serve as baffles) or through external 'limpet' coils

on the jacket of the vessel. These coils consist of continuous lengths of pipe welded in

a shallow spiral round the vessel. This cooling water system is also used to cool batched

medium sterilized in the vessel prior to its inoculation.

3.3.3 Defoaming agents and instrumentation

Microbial cultures may foam when they are subjected to vigorous mechanical stirring

and aeration. If this foaming is not controlled, culture is lost by entrainment in the

exhaust gases and so there are systems, often automatic, for detecting incipient foaming,

Manufacture of antibiotics 153

for temporarily applying backpressure to contain the culture within the vessel and for

the aseptic addition of defoaming agents.

Instrumentation is also fitted to provide a continuous display of important variables

such as temperature and pH, the power used by the electric motor, airflow, dissolved

oxygen and exhaust gas analysis. Manual or computer feedback control can be based

either directly on the signals provided by the probes and sensors or on derived data

calculated from those signals, such as the respiratory coefficient or the rate of change

of pH. Mass spectronomical analysis of exhaust gases can provide valuable physiological

information.

3.3.4 Media additions

Not all the nutrients required during fermentation are initially provided in the culture

medium. Some are sterilized separately by batch or continuous sterilization and then

added whilst the fermentation is in progress, usually via automatic systems that allow

a preset programme of continuous or discrete aseptic additions.

3.3.5 Transfer and sampling systems

Aseptic systems are provided to transfer the inoculum to the vessel, to allow the taking

of routine samples during fermentation, for early harvesting of aliquots when the vessel

becomes full as a consequence of the media additions and to transfer the final contents

to the extraction plant when fermentation is complete. Asepsis is assured by engineering

design and by steam, which must reach all parts of the vessels and associated pipework.

Any pockets of air or rough surfaces that steam does not penetrate could act as reservoirs

for contaminating microorganisms.

Sampling is essential to monitor the amount of growth, the running levels of key

nutrients and the penicillin concentration. It is necessary also to check that there has

been no contamination by unwanted microorganisms.

3.4 Control of the fermentation

Should oxygen availability fall below a critical level, benzylpenicillin biosynthesis is

greatly reduced although culture growth continues. Thus, if growth in the fermenter

proceeds unchecked at the rate prevailing in the seed stages, the culture would become

very dense and the available aeration would no longer be sufficient to maintain penicillin

production. Accordingly, conditions are so adjusted that fast growth is achieved only

until the cell population has reached the maximum density that the vessel can support.

Further net growth is constrained by deliberately limiting the supply of a key nutrient

(in practice, a sugar). The cells can then be stimulated to an 'overproduction' of

benzylpenicillin while restricting the amount of growth and a stable, highly productive

cell population can be sustained.

Batched medium

The medium initially placed in the fermenter is a complete one but designed only to

3.4.1

154 Chapter 7