Housden M. Hitler. Study of a Revolutionary? (2000)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

188 Hitler: Study of a revolutionary?

orator who knew how to motivate a dynamic following. Initially he grasped the

political initiative to pursue violent, illegal action which in 1923 culminated in a direct

revolt against the state. Failure at this point led to imprisonment and (despite his

enduring revolutionary instincts) compelled him to seek power not through direct

action, but through the parliamentary process. As a result Hitler changed to a

position of pseudo-legality from which he still managed to threaten and glorify

violence against both the republican state and his enemies.

‘Dictator’ discussed whether Hitler led National Socialism as a revolutionary

movement and the Third Reich as a revolutionary state. Through the abolition of

civil rights in Germany and the supersession of rule by multi-party democracy, he

brought about a fundamental change to the constitution of the nation’s political

power. He presided over institutions which meted out violence against perceived

opponents and attempted to root them out as social ills. This was done to left-wing

activists and Jews in particular. By necessity the actions implied changes to

Germany’s social structure. The sort of violence Hitler unleashed across the

country was illegal by any reasonable standards. From this chapter Hitler emerged

as a ruthless manipulator of everything around him – people and political

organisations alike. It was a style of leadership which enabled him to motivate

followers to implement his desires. As Reich Chancellor he embarked on a

significant effort to mobilise behind him as much of the nation as possible. Even

when possible limitations to Hitler’s revolutionary credentials were identified (e.g.

the facts that he came to power in a coalition cabinet with traditional conservatives

and that he refused to try to Nazify the army at an early point), these were

explained as short-term measures to improve the prospects for bringing about

subsequent lasting change.

The chapter ‘Deceiver’ asked if there can be a revolutionary foreign policy and

whether Hitler implemented one. Certainly it reiterated the image of the man as a

motivator. Foreign policy triumphs rallied the German people behind him. He

displayed substantial initiative, toughness of mind, self-confidence and ruthlessness

as he lied to and bullied Europe’s statesmen to achieve his objectives. Transcending

the reasonable approaches of his predecessors such as Stresemann and Rathenau,

Hitler showed a readiness for violence in dealing with Austria and Czechoslovakia.

Illegally he supported fifth columns abroad. As first came to light in the chapter

‘ldeologue’, Hitler championed completely new legitimating principles and myths

for the implementation of foreign policy. Through a programme of the most radical

imperialist expansion he hoped to rectify perceived social ills facing Germany, such

as the danger of over-population. By early 1939 he had taken the initiative to pursue

aggressively expansionist ends. He overturned the Versailles system (which he had

always despised as unjust) and transformed the constitution of political power in the

international arena. If anything ever constituted a revolutionary foreign policy, this

was it.

‘Warlord’ raised the possibility that the Second World War was led as a

revolutionary conflict. From 1939 on, Hitler applied political violence across Europe

to alter the constitution of international and national power structures in the most

Conclusion: study of a revolutionary? 189

direct and radical of ways. The single-party nation gave way to the single-party

continent as country after country toppled before Hitler’s armies. In the process,

Europe was edged along the road to becoming a function of Germany’s needs as

Hitler defined them. From the outset Hitler embarked on a project to transform the

social structures of the nations his forces occupied. This was evident in plans to

eradicate Polish intellectuals and to resettle Polish lands with ethnic Germans. He

took the initiative in 1941 and escalated the conflict with an assault on the Soviet

Union. The nature of warfare was redefined by a series of orders sponsored by

Hitler which must be defined as illegal by any reasonable standards. Massive plans

for extermination (of Communists, Jews and Slavs) became part and parcel of the

war in the East such that Hitler championed the most radical political and social

transformation of the whole continent. There is no doubt that he used war as a

means to export his revolutionary principles (both in the way it was fought and in

the occupation policies which followed his victories) and used the period 1939–45

as an opportunity to realise his ideas in their most murderous form. The extremity

of the exterminatory actions expressed thought that was ‘black and white’, violent

and idealistic in equal measure. In Hitler’s mind the bases of evil were being

destroyed as a means to eradicating social ills (e.g. Jewry and Communism) which

were perceived as threatening Germany. The seizure of land was a means to solving

the perceived social ill of over-population.

The chapter ‘Artist and architect’ explored how Hitler’s artistic conceptions

related to his revolutionary credentials. Here the most significant potential flaw in

his revolutionary character came to light. Hitler’s tastes, which revolved around

grandeur, classicism and insipid pastoralism, were hardly a break with tradition.

They were a reaction against the way the contemporary arts had been developing

since about 1910. Hitler was no supporter of the cultural modernisation which

Germany experienced after the First World War. But this does not mean that his

approach to the arts lacked everything revolutionary. On the one hand, he

introduced racism as a new source of legitimation defining the type of artistic

expression he expected in Germany. On the other hand, he wanted to use ‘racially

sound’ construction projects to establish a national myth supporting principles of

community, national greatness and the permanence of his political values. If we

interpret Hitler’s approach to the arts as a propagandistic device to reinforce the

wider changes to political systems and social structures which he brought about

across Europe, even this aspect of his life becomes revolutionary.

Finally ‘Mind’ addressed whether Hitler had a revolutionary personality. Worries

about his mortality and drug abuse encouraged him to accelerate and radicalise his

policies from the late 1930s. The latter must have boosted his self-confidence and

ruthlessness. In terms of Hitler’s experiencing a personality disorder, it has been

proposed that he suffered from an Oedipal complex. This possibility was left to one

side for lack of evidence. Instead it was proposed that at the end of the First World

War, while stressed and depressed in Pasewalk hospital, Hitler suffered a paranoid

psychotic episode which mobilised his mind against Jews and encouraged him to

understand the world in terms of a Darwinian struggle of each against the other.

190 Hitler: Study of a revolutionary?

This experience, which was never treated properly, added a significant dynamism to

his subsequent political career.

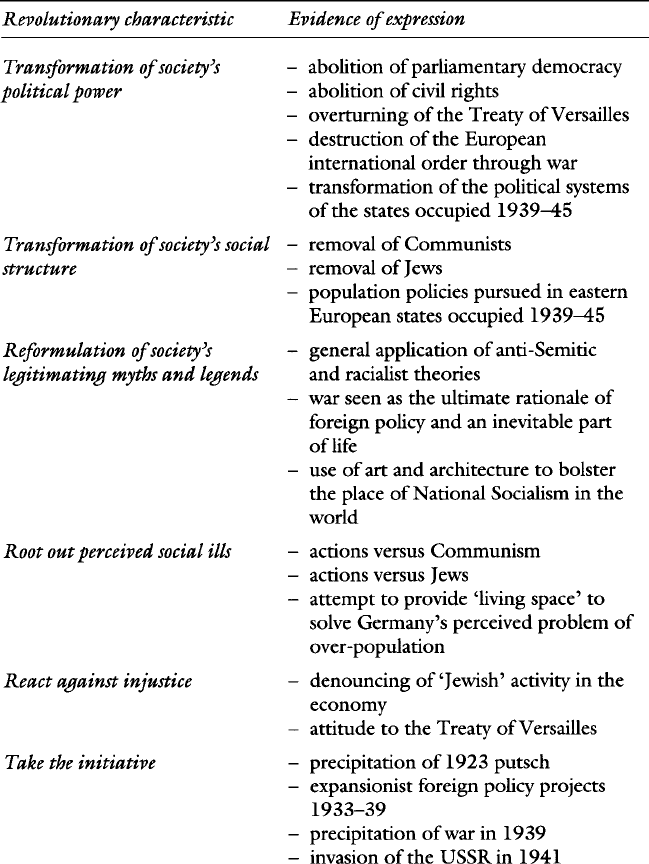

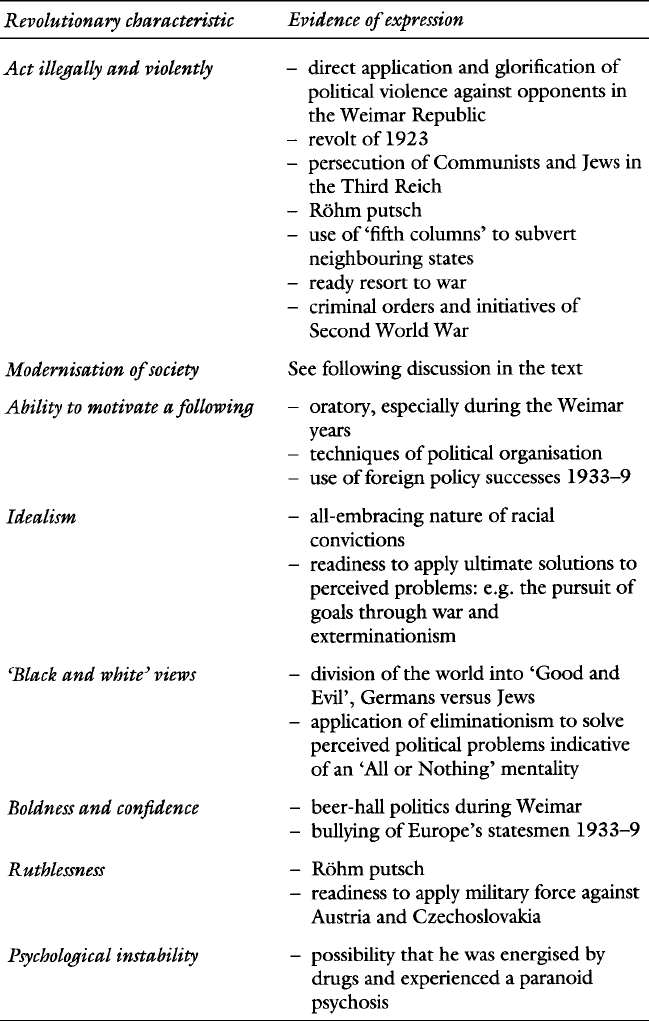

A careful tracing of these comments shows that Hitler’s life covered all of the

definitional characteristics of what it is to undertake a ‘revolution’ and to be a

‘revolutionary’. The main points are summarised in the table here.

Summary of Adolf Hitler’s revolutionary credentials

Conclusion: study of a revolutionary? 191

192 Hitler: Study of a revolutionary?

Just one important issue has been left largely to one side (as indicated in the table):

the aim of modernising or improving the world. Strong cases have been made by a

number of historians that fascists, Hitler along with them, were fundamentally

reactionary. The nature of Hitler’s artistic tastes supports the proposition. Famously,

in the 1960s Ernst Nolte argued that Hitler’s National Socialism was a rejection of

historical progress (Nolte, 1969, p. 529). Recent interpretations have maintained the

image of a strongly conservative strain in the movement. Jeffrey Herf has coined the

phrase ‘reactionary modernism’ to describe Hitler’s politics. It applied modern

techniques to promote ends which were still fundamentally reactionary (Herf, 1984,

pp. 1–2).

It is easy to see Hitler’s central fixation on racism as a kind of throwback. Anti-

Semitism has existed for millennia and there was certainly nothing new about anti-

Slavic prejudice in either Germany or Austria (Herbert, 1997, chapter 2; Mason,

1988, p. 11). It is impossible to deny there was something atavistic about the passion

and intensity Hitler brought to his prejudice. This should be no surprise if we are

right that it was energised significantly by a bout of mental ill-health experienced at

the end of the First World War (see Chapter 8). But there was more to his hatred

than just this. Its expression was actually quite complex, as were the initiatives it

spawned. As early as his first anti-Semitic tract (see document 2.2), Hitler said his

aim was to transcend the traditional ‘pogrom’ mentality (which characterised

established anti-Semitism) in favour of something else, by implication something

new. Hitler was not interested in just expressing hatred of Jews. He expected their

removal from society to herald the creation of a different society, by implication a

better one (Baumann, 1989, p. 91). It is also quite correct that, once Reich

Chancellor, Hitler’s practical objective of trying to create a community without

‘lesser races’ was not ‘a form of regression to past times’. No comparable project

had ever been attempted before in German history (Burleigh and Wippermann,

1991, p. 301).

This was an initiative whose time had come. Debates about biological and social

engineering were well-established in circles of German life beyond National

Socialism. Since at least 1895 they had involved some established intellectuals. As a

result one historian has concluded that the morality of biological engineering is not

so much a problem of fascism, but one of modernity (Schwartz, 1998, p. 619). Not

even Hitler’s wartime efforts to restructure Europe’s populations can be divorced

from modern trends of thought. During the 1920s and 1930s German scientists

embarked on significant projects to assess objectively the extent to which eastern

European states were over-populated (Aly and Heim, 1993, pp. 72–82 and 104–

19). The implication was that something had to be done to improve the economic

efficiency of eastern European societies. In this light, Hitler’s plans to depopulate

the East through genocide can be linked to ideas that were current at the time among

progressive economists and demographers (Aly and Heim, 1993; Housden, 1995, p.

479). Even his eliminationism cannot be divorced entirely from notions of

purposeful, progressive change (Baumann, 1989, pp. 91–2).

Wider perspectives add more to the understanding of Hitler’s career. While

Conclusion: study of a revolutionary? 193

National Socialism was the most obvious political movement to promote racial

hygiene this century, it was far from the only one. Increasingly today the measures

pursued in Germany are being understood as encapsulating ‘merely one offshoot

of an international movement with many national variations’ (Quine, 1996, p. 134).

Even admitting that the fixation on excluding Jews from the community was singular

to Hitler’s politics, legislating about what constituted acceptable sexuality (as he

outlined it in the Nuremberg Laws, document 4.18) was not. At about the same

time Hitler was pursuing his ends in the Third Reich, democracies such as the USA

‘implemented aggressive and activist policies aimed at biological engineering and

social regimentation’ (Quine, 1996, p. 136). In the end, it is inescapable that during

the early half of the twentieth century, biological and social engineering were

widely believed to be valid components of strategies to improve and modernise

society.

So even if it is accepted that, objectively speaking, something about Hitler’s

prejudice spoke of a primeval force at work, there are still compelling grounds for

maintaining that when he peddled his racism, in the ‘rational’ part of his mind Hitler

believed he was pursuing a radical new policy, fit for the times, which was tailored to

bringing about the improvement and modernisation of Germany. In terms of what

was accepted as valid during his lifetime, Hitler’s application of prejudice (not to

mention the fact that he found people ready to go along with it) cannot be divorced

from the context of the modern world and modern ideas (Baumann, 1989, p. xiii).

The way his racism was expressed and applied was only conceivable in the early

twentieth century (Payne, 1995, pp. 483–4). It may have offered an alternative view

to that which is generally held about progress today, but it was not a rejection of

that which at the time in the minds of many people constituted bona fide elements of

modernity and the process of modernisation (Griffin, 1993, p. 47). In the last

analysis (and whatever the exact nature of the forces which generated it) Hitler’s

racism cannot simply be used to define him as a reactionary. It spoke of a

revolutionary whom history subsequently showed to have got things wrong.

This is indeed the study of a revolutionary. The proposition is true regardless of

the limiting points touched on here, for example, Hitler’s participation in Germany’s

electoral process, his coming to power in a coalition government, his reluctance to

Nazify the armed forces quickly and his reactionary artistic tastes. With this said,

even if, like Karl Dietrich Bracher, we want to maintain that Hitler was an inferior

individual (for instance intellectually) in comparison to other revolutionary figures

such as Rousseau, Robespierre, Napoleon, Marx, Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin, still it

has to be recognised that he actually fulfilled the roles of all of them put together.

He compiled a most extensive set of revolutionary goals (calling for radical social

and political change); he mobilised a revolutionary following so extensive and

powerful that many of his aims were achieved; he established and ran a dictatorial

revolutionary state; and he disseminated his ideals abroad through a revolutionary

foreign policy and war. In short, he defined and controlled the National Socialist

revolution in all its phases (Bracher, 1976, p. 206). Even taking his shortcomings into

account, a good case remains for saying that Hitler approximated to ‘the prototype

194 Hitler: Study of a revolutionary?

of a revolutionary’ (Bracher, 1976, p. 206). With this established, we can provide

five final theses about the nature of Adolf Hitler. These grow out of a series of

central observations highlighted during the course of the study.

Thesis I : In Adolf Hitler’s revolutionary life, ideas provided a continuity which

determined actions.

Of course not everything Hitler said and wrote before 1933 was realised thereafter,

but enough did come to pass to underline the validity of the proposition. He

denounced Marxist Socialism in the pages of Mein Kampf and as soon as he was

dictator took decisive steps against its appearance in Germany. He spoke and wrote

about anti-Semitism at length in the 1920s and from 1933 pursued an ever more

radically anti-Semitic path. He first wrote about the need to establish a sizeable core

of Germandom in central Europe and subsequently set out to achieve this. He wrote

about a Lebensraum empire and then pursued it through war. As both a teenager

and during the 1920s he created architectural plans which he set about realising once

he was in charge of Germany. Adolf Hitler shaped the world as he did because he

believed consistently that to do so was correct.

This position looks at variance with that championed by Hans Mommsen. He has

argued that Nazi ideology and Hitler’s personality are not enough to explain policy

formulation in the Third Reich (Mommsen, 1976, p. 156). He believes Hitler only

became involved in formulating Germany’s domestic policy rarely and, like Karl

Schleunes, does not accept for a minute that Hitler ever had a systematic plan of

how to approach the Jewish Question (Schleunes, 1970, p. 257; Mommsen, 1976, p.

227 1991, p. 233). Only hindsight gives a sense of consistency and ideological pre-

determination to events as they unfolded. Policy in the Third Reich came into effect

largely through a process called ‘cumulative radicalisation’ (Mommsen, 1976, p.

156). This involved government functionaries losing their sense of reality and

radicalising their actions as they struggled to function in a state system that was

corrupt, which could be self-contradictory and which engendered dramatic

competition between operatives. Amidst the organisational chaos, policy

developments took on a dynamism all of their own. Only such a train of events

could ever have brought into sight, as actual goals of policy, the sort of metaphorical

statements (including extreme racialist pronouncements) Hitler made in keynote

speeches (Mommsen, 1991, pp. 236–7).

Mommsen’s analysis is intellectually challenging and does reflect the

administrative complexity which characterised the Hitler state. But just because a

state system was terribly ill-defined and ‘irrational’ does not actually mean it failed

to do exactly what the person leading it always wanted. Mommsen himself accepts

that Hitler’s personal ideas certainly did involve the destruction of the Jews and

other entire populations (Mommsen, 1976, p. 234). There is no sign that the Third

Reich brought about initiatives Hitler did not want to see happen, and there is no

question that he ever considered preventing the steady radicalisation of the

treatment of Jews (Schleunes, 1970, p. 259). All the signs are that for the key areas

of his government, Hitler’s beliefs were absolutely central (Dülffer, 1996, p. 293). In

Conclusion: study of a revolutionary? 195

other words, even if some process of ‘cumulative radicalisation’ did operate within

the Hitler state, pushing its functionaries down particular avenues of policy, the

impression remains that the system was only achieving exactly the sort of

‘ideological drive’ Hitler wanted anyway (Kershaw, 1995, p. 336). In the last

analysis, Hitler established the state and was responsible for the way it worked. The

system he presided over was orientated decisively towards important goals he

believed in personally. No matter how exactly it functioned, it is inescapable that

when it really mattered the Third Reich provided a pretty effective platform for its

dictator and his ideas. Notwithstanding Mommsen’s analyses, the truth of this

thesis stands.

Thesis 2 : Adolf Hitler was a racial revolutionary.

In establishing his project for the internal constitution of Germany, and especially in

his planning for her external expansion, Hitler was prepared to give pride of place to

what he deemed racial necessities. In this light Hermann Rauschning’s idea, expressed

long ago, that Hitler led a ‘revolution of nihilism’, which lacked any fixed aims, is

wrong (Rauschning, 1939a, pp. xii and 23). National Socialism did stand for something:

the radical denial of universal values to mankind (Sternhell, 1994, p. 251).

Under Hitler, Germany saw a completely new kind of racial revolution (Hauner,

1984, p. 670). He spoke to audiences in Munich’s beer halls as a convinced anti-

Semite; he led the nation as an anti-Semitic dictator; he fought the Second World

War as a convinced racist; he theorised about art in the same way he theorised

about politics, economics and history, namely in the manner of a prejudiced zealot.

Hitler breathed a bigotry which found the most profound form of expression in

everything he did. Daniel Goldhagen has taken the analysis of this reality to its logical

conclusion. He says that radical racial convictions and an appropriate agenda made

Hitler and his followers the ‘most profound revolutionaries of modern times’. They

brought about a revolution that was the ‘most extreme and thoroughgoing in the

annals of western civlization’ (Goldhagen, 1996, p. 456). It is hard to quibble with

the point.

With this said, Rainer Zitelmann’s equating of Hitler’s movement with

Communism (see Chapter 1) runs the risk of becoming misleading. This is so

despite the very well-documented cross-over of party memberships which occurred

during the later 1920s and early 1930s between followers of the German

Communist Party and the NSDAP, and also despite the fact that the two movements

certainly did compete for the same votes (Fischer, 1991, p. 117 and chapter 8;

Housden, 1993, pp. 478–9). Document 3.12, which advertises a Nazi meeting,

actually specified that Communists and Socialists could attend the event free of

charge. But Hitler was not just anti-Communist because the two movements

sometimes competed for the same supporters and tended to use comparable

political techniques. These points are superficial and do not get to the heart of

Hitler’s attitude towards Communism. Before he was even a V-Mann (see Chapter

3), Hitler hated Marxism enough to denounce soldiers who had sympathised with

the Munich uprising. As his thinking grew, he equated Communism with Judaism

196 Hitler: Study of a revolutionary?

and allocated it to the ranks of all that was truly evil in the world. As with his stance

on the Jewish Question (and appropriately since he understood the two as

overlapping categories), there was never really any way back from this position. It

was logical that the invasion of the Soviet Union was conceived in a particularly

bloody way and became enmeshed with the implementation of the Holocaust. The

ultimate ‘land grab’ was at the same time the ultimate racial action. Hitler and

Communists may both be classified as revolutionaries, but Hitler was certainly not

a closet Bolshevik. He was something else: a racial revolutionary who understood

Communism as a racial phenomenon that required eradication.

Thesis 3 : Adolf Hitler was a turn-of-the-century revolutionary.

We have accepted that Hitler wanted to solve society’s ills by the application of his

own ideas and that he wanted to see social improvement and modernisation according

to his understanding of the terms. The irony is that much of his thinking for the

future was rooted in the past. The primitive side of his prejudice has been mentioned

in this chapter already. More specifically, he took intellectual inspiration from the

world as it was particularly before 1914. In the field of politics he looked to the turn-

of-the-century anti-Semites, Schönerer and Lueger. As regards ideology, he was

inspired by the racial fantasies which were abroad in pre-war Austria. Hitler’s ideas

about foreign policy built on paradigms that had been well-established in right-wing

circles before 1914 and which could be found among the members of the General

Staff during the First World War. As an artist he rejected all developments since

about 1910; in music he was enthralled by Richard Wagner (who lived from 1813 to

1883); in architecture he revelled in the classicism of the late nineteenth century.

That Hitler owed much to the past does not at all invalidate his revolutionary

status. It should be expected. All revolutions draw on references from history

(Weber, 1976, p. 514). The bible of revolutionary Marxism, The Communist

Manifesto, was written in 1847–8. That twentieth-century figures from Lenin to Che

Guevara drew on it hardly lessens their revolutionary status. The point only serves

to support the truth of Billington’s argument that the revolutionary fervour of the

twentieth century grew out of that previous one (Billington, 1999, p. vii). The

nineteenth-century cultural movements experienced in Germany, as exemplified

especially by Wagner’s artistic projects, were revolutionary in the widest sense

(Rose, 1990, p. 16). The nationalist anti-Semitism of that period was similar. It

promised the ‘moral regeneration of the German people’ through the removal of

Jews (Rose, 1990, p. 18). It is just an empirical fact that the revolutionism begun

during this earlier time provided the inspiration for, and found its ultimate

expression in, the minds of men like Adolf Hitler in the wake of the First World War.

Even if there were few completely new principles in his thinking, he did build upon

the pre-existing foundations with the important characteristics of rigour, scale,

passion and total want of moral restraint. Colossal classical building projects and

colossal exterminationism: the traits were intimately related and spoke of an

intensity of belief, commitment and idealism which was nothing if not revolutionary

(Billington, 1999, p. 3).

Conclusion: study of a revolutionary? 197

Thesis 4 : The normal and pathological mental worlds of Adolf Hitler corresponded

closely. This proximity helped render him particularly energetic and at times

precipitative. It predisposed him to revolutionary action.

The key ideological tenets of Hitler’s life, namely anti-Semitism (linked to the fear of

global Jewish conspiracy) and a belief that life is a struggle for existence, fitted together

well, and expressed the paranoia associated with a psychotic delusional experience.

The result of this overlap could only be a flowing together of motivation stemming

from the ‘rational’ thoughts of the individual (i.e. that a course of action should be

pursued because it seems intellectually supportable) and from the pathological (i.e.

that a course of action should be pursued because paranoia dictates as much). The

result helps account for the profound energy Hitler showed throughout much of his

life, as well as his capacity to dash towards showdowns. If he wanted, he could always

find reasons to act today, rather than wait until tomorrow. For example, in 1939

economic problems became grounds to invade Poland, not reasons to defer action.

In 1940/41 the need to defeat Britain militarily became (after an initial hesitation) a

justification to race eastwards against the USSR; it was not a reason to bide one’s

time. Likewise in 1941 Hitler’s belief that the Soviet armed forces had to be weak

held sway over his understanding that, once war was declared, anything could happen.

This perspective on the causal mechanism which lay behind Hitler’s actions is

supplementary to what we know of other issues, such as drug abuse, fears for his

health and the concrete circumstances in which given political decisions were taken.

It goes without saying that the coalescence of drives predisposed Hitler to take

revolutionary measures. The intensity of belief and fixity of purpose this coalescence

must have engendered also helps explain why he never wavered in his determination

to realise a set of ‘visions of forceful change and domination’ (Bracher, 1976, pp.

205–6). Without such singlemindedness, the history of Germany and Europe would

have been very different.

Thesis 5 : Adolf Hitler was a criminal revolutionary.

According to our definition, all revolutionaries act outside the law. But Adolf Hitler

was not just interested in petty crime. He did not infringe the law only here and

there as a short-cut to the creation of a better world for the vast majority of its

inhabitants. He was a criminal in the first degree. His politics became the premeditated

mass murder of vast swathes of Communists, Slavs and Jews. Even his hope that the

aim of civilisation should be the production of great works of art was fatally

compromised by the conviction that race determines artistic sensitivity. Had he

survived 1945, his only hope at a war crimes trial would have been to plead insanity.

At the time no one would have listened. He had been the initiator of far too much.

The extent of his criminality underlines the fact that Hitler’s revolution was only ever

perceived to be modernising. There was a terrific gulf between conception and reality.

Principles of division, hatred and murder are hardly the lasting values of mankind.

The actuality of the revolution which shook Europe between 1933 and 1945 was

hopelessness: it led nowhere worth going. So although his figure undeniably exerts a

voyeuristic fascination even today, and notwithstanding so much being written about