Hillstrom K., Hillstrom L.C., Baker L.W. (ed.) - American Civil War. Almanac

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

captured the abolitionist and his crew

after a brief but bloody battle. Brown

and the remnants of his band were led

away, leaving behind several dead

civilians, including the mayor of

Harpers Ferry, and ten dead abolition-

ists. Brown and seven of his men were

subsequently convicted of murder,

treason, and inciting a slave insurrec-

tion, and they were all executed. But

Brown remained defiant during and

after his trial. “This Court acknowl-

edges, as I suppose, the validity of the

law of God,” he proclaimed after

being sentenced to hang. “I believe

that to have interfered as I have done,

as I have always freely admitted I have

done in behalf of His despised poor, is

no wrong, but right. Now, if it is

deemed necessary that I should forfeit

my life for the furtherance of the ends

of justice, and mingle my blood fur-

ther . . . with the blood of millions in

this slave country whose rights are dis-

regarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust

enactments, I say let it be done.”

Brown’s death further

divides America

Brown’s actions at Harpers

Ferry—and his execution a few weeks

later—had a major impact on commu-

nities all across America. In the North,

reaction was mixed. Many people crit-

icized Brown’s violent methods, and

most Northern lawmakers agreed with

Senator William Seward (1801–1872)

of New York, who called the abolition-

ist’s execution “necessary and just.”

But many other Northerners saw

Brown as a heroic figure who was will-

ing to die for his beliefs. A number of

Northern communities tolled church

bells on the day of his hanging as a

way of saluting his efforts. Many abo-

litionists throughout the North

praised him for his bravery and his ha-

tred of slavery. Writer Henry David

Thoreau (1817–1862), for instance,

spoke for many Northerners when he

called Brown “a crucified hero” and an

“angel of light.”

In the South, on the other

hand, Brown’s raid cause a wild ripple

of fear and hysteria throughout white

communities. Even though Brown

had been unable to rally a single slave

to his side, whites still remembered

the bloody slave rebellion of 1831 led

by Nat Turner (1800–1831). Many of

them became convinced that antislav-

ery forces in the North were willing to

sacrifice the lives of thousands of

Southern whites in their zeal to end

slavery. The reaction to Brown’s exe-

cution in some parts of the North fur-

ther increased Southern anger and

fear. To many whites in Alabama, Mis-

sissippi, South Carolina, and other

slave states, the Northern threat to

their way of life had never seemed

more real or immediate.

The 1860 presidential

campaign

The 1860 campaign for the

presidency of the United States was

waged under a dark cloud of anxiety

and fear. Some Southern politicians

and newspaper editors warned that

the region was prepared to secede

from the Union if an antislavery

politician was elected president.

1857–1861: The South Prepares to Secede 61

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 61

selected their candidates for the 1860

election.

The Republican Party knew

that it would not get any votes in the

South because of its reputation as a

party devoted to a strong central gov-

ernment and antislavery positions.

But the Republican leaders believed

that their candidate might still win

the election if he could make a good

Northern reaction to this threat was

mixed. Some people thought that

threats of secession were just words

designed to scare Northern leaders

into abandoning abolitionist posi-

tions. Others recognized that the

South’s threats needed to be taken se-

riously, but continued to maintain

their belief that slavery had to be

stopped. It was in this environment

that America’s major political parties

American Civil War: Almanac62

The United States elects its presi-

dent and vice president through an institu-

tion known as the electoral college. The

electoral college consists of a small group of

representatives from each state legislature,

called “electors,” who gather in their re-

spective states to cast ballots in elections for

the presidency and vice presidency of the

United States. These elections take place

every four years. Historically, the electoral

college meets one month after the public

vote for the president and the vice presi-

dent. When the electoral college meets,

each state elector casts his or her ballot for

the candidate who received the most pop-

ular votes in that state. Electors are not

legally required to vote for the candidate

who received the most popular votes in the

state, but they are honor bound to do so.

After the electoral college results are tallied,

the person who receives a majority of avail-

able electoral votes around the country is

declared president, and his or her running

mate assumes the position of vice presi-

dent. The offices of the president and the

vice president are the only elective federal

positions that are not filled by a direct vote

of the American people.

The rules of the electoral college

call for each state to be represented by a

number of electors that is equal to the total

of its U.S. senators and representatives in

Congress. All states are represented by two

senators, but states with large populations

are given greater representation in the U.S.

House of Representatives than are states

with smaller populations. As a result, they

also receive a greater number of electoral

votes in presidential elections.

As of 1999, there are a total of 538

members in the electoral college. This

means that presidential and vice presiden-

tial candidates can only be elected if they

win a majority (270 or more) of those 538

votes. In modern elections, heavily popu-

The Electoral College

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 62

showing in the more populous North.

(Since more people lived in the North

than in the South, the Northern states

also had more votes in the electoral

college, the institution that deter-

mines who the nation’s next president

will be). With these factors in mind,

the Republicans chose Abraham Lin-

coln as their candidate. They believed

that Lincoln’s moderate reputation

and the party’s pro-business and anti-

slavery positions would attract a wide

range of voters in the North.

The Democratic Party, mean-

while, had a terrible time deciding who

its nominee would be. In April 1860,

when the party’s leaders gathered to

reach agreement on its presidential

candidate and its major campaign is-

sues, the Democrats stood as the only

political party in America with a na-

1857–1861: The South Prepares to Secede 63

lated states like California, New York, Flori-

da, and Texas have had a far greater num-

ber of votes in the electoral college than

sparsely populated states like Wyoming,

North Dakota, and Delaware. The only

other territory held by the United States

that has any electoral votes is the District of

Columbia, which was given three electoral

votes by a 1964 law.

The electoral college system has

been in place in America ever since it be-

came a country, but many people have

criticized it over the years. The primary

complaint that has been raised about the

system is that it makes it possible for a can-

didate to become president without win-

ning a majority of popular votes. In fact, on

three different occasions in American histo-

ry—1824, 1876, and 1888—the electoral

college has selected a candidate who re-

ceived fewer popular votes than another

candidate. In other words, the candidate

that was supported by the most voters did

not win the election.

In 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes

(1822–1893) received fewer popular votes

than Samuel J. Tilden (1814–1886), but

won the election by an electoral vote of

185 to 184. In 1888, Benjamin Harrison

(1833–1901) defeated incumbent president

Grover Cleveland (1837–1908) in electoral

votes, 233-168, even though Cleveland had

received more popular votes. And in 1824,

although Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) re-

ceived more popular and electoral votes

than John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), he

had not earned a majority of electoral

votes, as two other candidates won a total

of 78 votes. In a special vote in the U.S.

House of Representatives, Adams eventually

gained enough support to defeat Jackson.

Despite such results, however, periodic at-

tempts to change or abolish the electoral

college have always failed.

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 63

When Northern Democrats refused to

go along with this demand because of

its certain unpopularity in their home

states, a large group of radical proslav-

ery Southerners—sometimes known as

“Fire-Eaters”—walked out of the con-

vention in protest. Two months later,

a second Democratic convention was

held, but it, too, ended in failure, as

the two sides bickered over the slave

code idea.

In the end, the Northern and

Southern wings of the Democratic

Party could not agree on the slavery

issue, and they ended up nominating

two different candidates for president.

The Northern wing nominated

Stephen Douglas, the Illinois senator

who had defeated Lincoln in the 1858

Senate elections. Douglas was a strong

candidate in the North, but he was no

longer popular in the South because of

his opposition to the Lecompton Con-

stitution and his support of popular

sovereignty, which Southern leaders

now opposed. Dissatisfied with Dou-

glas, the Southern wing of the Democ-

ratic Party decided to nominate Vice

President John C. Breckinridge

(1821–1875), a proslavery Kentuckian.

This decision to nominate a second

candidate shattered the party in two

and dramatically increased Lincoln’s

chances of victory.

Finally, a fourth candidate for

the office of the presidency emerged

in May 1860, when a group of politi-

cians from the former Whig Party

formed the Constitutional Union

Party. This group said that it was dedi-

cated to upholding the U.S. Constitu-

tional base of support. It remained

powerful in the North—although the

Republicans were gaining in populari-

ty—and it dominated politics in the

South because of the proslavery posi-

tions of Southern Democrats.

But as the Democratic conven-

tion got underway, it became clear

that the divide between the party’s

Northern and Southern wings had be-

come a serious one. As soon as the

convention opened, a radical faction

of proslavery Southerners insisted that

the party support the passage of a

“slave code” that would legally protect

slavery in all the western territories.

American Civil War: Almanac64

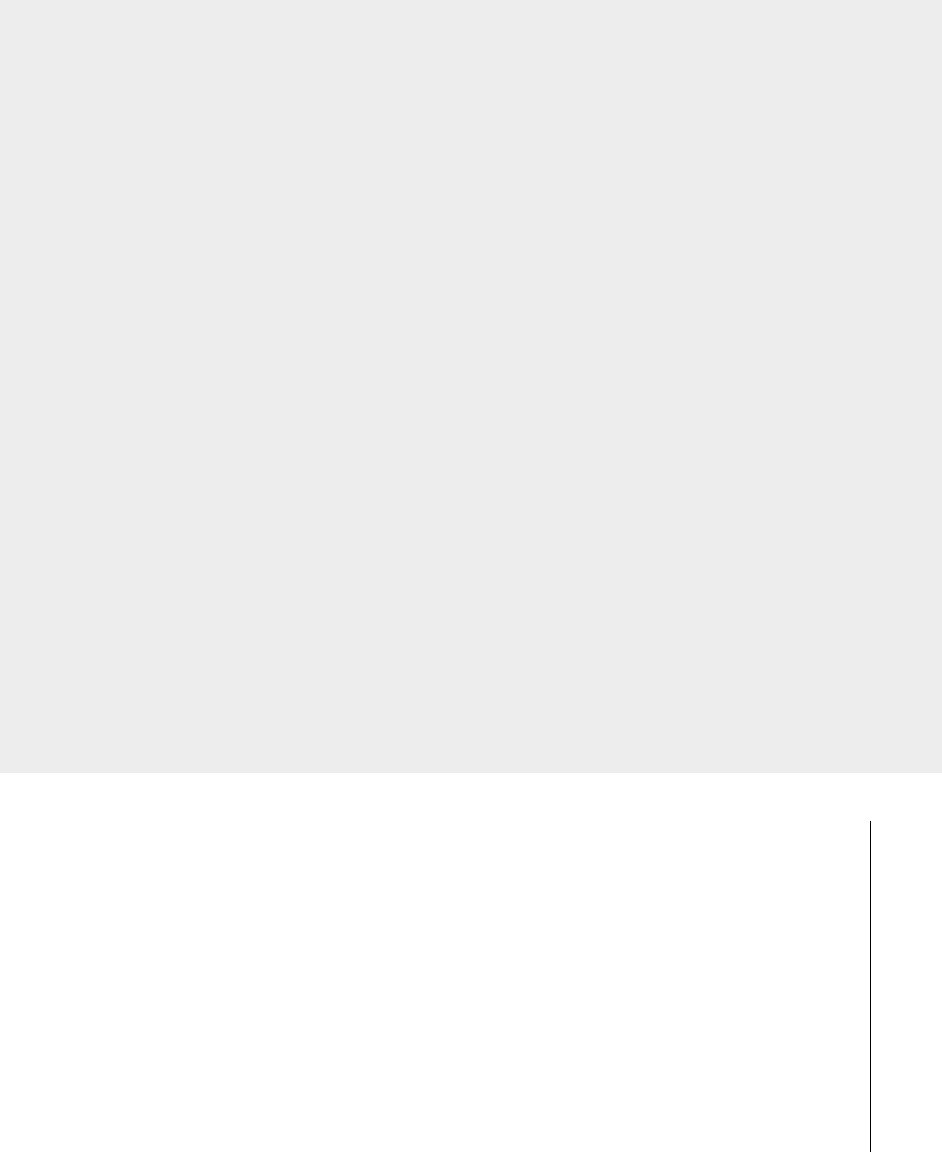

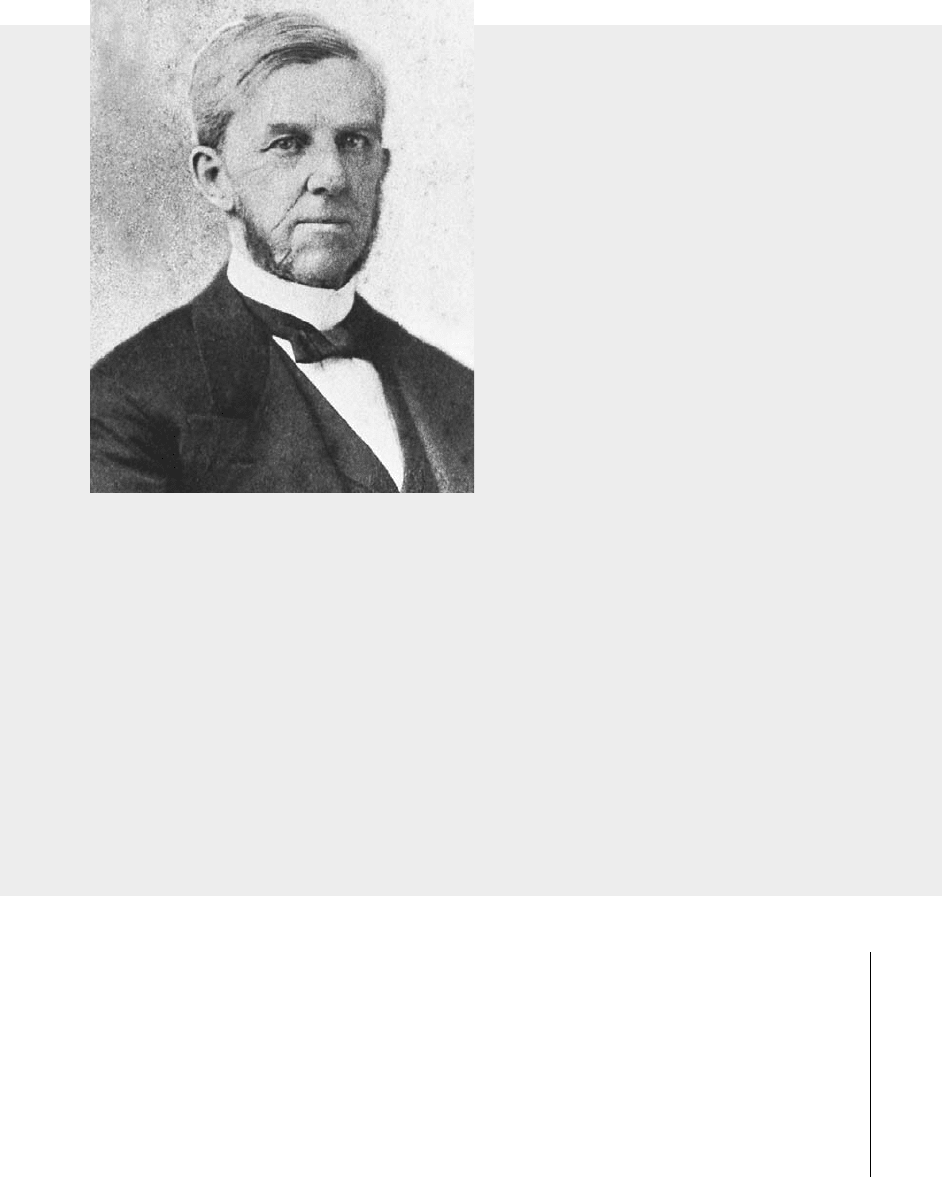

John Breckinridge. (Courtesy of the National

Archives and Records Administration.)

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 64

tion. But the party refused to take a

clear stand on slavery and other is-

sues, and its presidential candidate,

John Bell (1797–1869) of Tennessee,

looked unlikely to gather much sup-

port in the North or the Deep South.

Lincoln wins the election

In the weeks leading up to the

November election, anxiety about the

outcome was evident all over the

country. All of the competing parties

waged nasty campaigns, heaping

abuse on other candidates and warn-

ing of terrible consequences if their

candidate did not win the election.

The most serious of these warnings

was voiced in America’s Southern

states. All across the South, people

grumbled that if Lincoln was elected,

then they would have no choice but

to secede.

Lincoln knew how unpopular

he was in the South, so he did not

even bother campaigning there. In-

stead, he concentrated on beating

Douglas in the North, where most of

the nation’s voting population—and

most of America’s electoral votes—

were located. He knew that if he was

victorious in the North, he would

have enough electoral votes to secure

the presidency, no matter what hap-

pened in the South.

Despite widespread warnings

of secession from the South, Lincoln

was indeed victorious. He received

only 40 percent of the popular vote

(the actual number of citizens who

cast ballots) in the United States, and

his name was not even included on

the ballot in ten Southern states. But

he carried the entire North, capturing

54 percent of the region’s popular vote

and all of its electoral votes. Most of

the South went with Breckinridge, but

he was shut out in the North. Three

other Southern states sided with Bell,

but he too was unable to collect any

support in the Northern states. Dou-

glas, who only two years earlier had

defeated Lincoln in their famous Illi-

nois Senate race, ended up with 1.3

million popular votes, second only to

Lincoln’s total of 1.8 million votes. He

was the only candidate who received

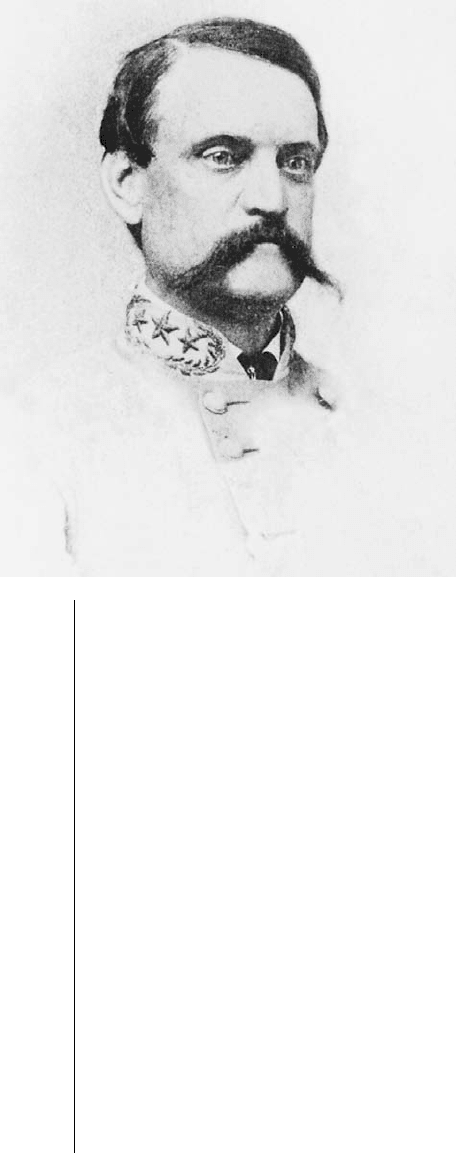

Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln was

elected president in 1860. (Reproduced by

permission of Corbis-Bettmann.)

1857–1861: The South Prepares to Secede 65

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 65

jority of Northern voters had decided

that his views were too friendly to

slaveholders. At the same time, most

Southern voters had reached the con-

clusion that Douglas would not fight

to extend slavery into America’s west-

ern territories.

significant support in all parts of the

country. But the “Little Giant” only

won two states outright (Missouri and

New Jersey), as his continued support

of popular sovereignty made him an

unsatisfactory choice to radicals on

both sides of the slavery issue. A ma-

American Civil War: Almanac66

When South Carolina announced

its intention to secede from the United

States, American lawyer and poet Oliver

Wendell Holmes (1809–1894) reacted with

sadness rather than anger. Holmes strongly

supported the Union, and he thought that

South Carolina’s decision was a rash one

that would bring pain and suffering to

North and South alike. But rather than

heap abuse or scorn on the state, he in-

stead composed a poem that reflected his

deep regret about South Carolina’s deci-

sion, as well as the hope of many American

citizens that the state—“Caroline,” the

Union’s “stormy-browed sister”—might

some day return to the Union in peace:

She has gone,—she has left us in

passion and pride,—

Our stormy-browed sister, so

long at our side!

She has torn her own star from

our firmament’s glow,

And turned on her brother the

face of a foe!

O Caroline, Caroline, child of the

sun,

We can never forget that our

hearts have been one,—

Our foreheads both sprinkled in

Liberty’s name,

From the fountain of blood with

the finger of flame!

You were always too ready to fire

at a touch;

But we said, “She is hasty,—she

does not mean much.”

We have scowled, when you ut-

tered some turbulent threat;

But Friendship still whispered,

“Forgive and forget!”

Has our love all died out? Have

its altars grown cold?

Has the curse come at last which

the fathers foretold?

Then Nature must reach us the

strength of the chain

That her petulant children would

sever in vain.

They may fight till the buzzards

are gorged with their spoil,

Till the harvest grows black as it

rots in the soil,

Till the wolves and the cata-

mounts troop from their caves,

“Brother Jonathan’s Lament for Sister Caroline”

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 66

South Carolina secedes,

other Southern states follow

On November 6, 1860, Lin-

coln was formally recognized as the

winner of the election, and the Ameri-

can South erupted in anger and de-

spair. Many white Southerners be-

lieved that Lincoln’s election meant

that a final Northern push to abolish

slavery throughout the United States

was just around the corner. Countless

furious speeches and editorials reflect-

ed the Southern certainty that the

1857–1861: The South Prepares to Secede 67

And the shark tracks the pirate,

the lord of the waves.

In vain is the strife! When its fury

is past,

Their fortunes must flow in one

channel at last,

As the torrents that rush from

the mountains of snow

Roll mingled in peace through

the valleys below.

Our Union is river, lake, ocean

and sky:

Man breaks not the medal,

when God cuts the die!

Though darkened with sulphur,

though cloven with steel,

The blue arch will brighten, the

waters will heal!

O Caroline, Caroline, child of the

sun,

There are battles with Fate that

can never be won!

The star-flowering banner must

never be furled,

For its blossoms of light are the

hope of the world!

Go, then, our rash sister! afar

and aloof,

Run wild in the sunshine away

from our roof;

But when your heart aches and

your feet have grown sore,

Remember the pathway that

leads to our door!

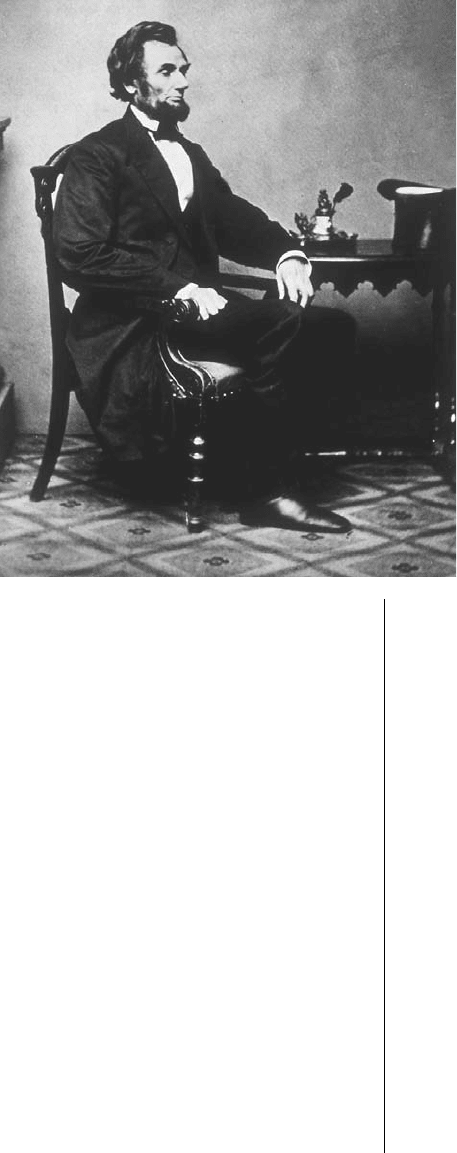

Oliver Wendell Holmes. (Courtesy of the Library of

Congress.)

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 67

weeks, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama,

Georgia, and Louisiana followed

South Carolina’s lead and announced

their secession from the Union.

Not all whites living in these

states were certain that secession was

the best course of action. Some South-

ern whites wanted to remain in the

Union despite the years of strain be-

tween America’s Northern and South-

ern regions. Others pointed out that al-

though a Republican had been elected

president, Democrats continued to

hold majorities in both the U.S. Senate

and House of Representatives. But as

Louisiana senator Judah P. Benjamin

(1811–1884) admitted, Lincoln’s elec-

tion had triggered a tidal wave of seces-

sionist sentiment that seemed to sweep

all other arguments out of its path. “It

is a revolution . . . of the most intense

character,” said Benjamin, “and it can

no more be checked by human effort,

for the time, than a prairie fire by a gar-

dener’s watering hose.”

“Yankees,” as the Northerners were

sometimes called, would soon begin

the process of reshaping Southern so-

ciety without regard for the feelings of

its white citizenry. The New Orleans

Daily Crescent, for example, charged

that the Republican Party’s primary

goal was to establish “absolute tyran-

ny over the slaveholding States,” and

bring about “subjugation [the con-

quering] of the South and the com-

plete ruin of her social, political, and

industrial institutions.”

As soon as Lincoln’s victory

was announced, calls for secession

from the Union could be heard all

across the South. South Carolina was

the first slaveholding state to act. Its

state legislature called a special meet-

ing to consider secession, and on De-

cember 20, 1860, state lawmakers

unanimously approved (by a vote of

169 to 0) a declaration that South Car-

olina was no longer a member of the

United States. Within the next six

American Civil War: Almanac68

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 68

I

n the first weeks of 1861, six Southern states began the

process of establishing their own government, even as

Northerners debated whether to let them leave the Union in

peace or use force to stop them. On February 23, two weeks

before Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) was inaugurated as the

sixteenth president of the United States, Texas became the sev-

enth state to leave the Union. After taking office, President

Lincoln reacted cautiously to these events. He felt very strong-

ly that the states that had seceded (left the Union) had no

right to do so, and he was determined to keep the Union to-

gether. But he also did not want to upset the large number of

states in the mid-South—sometimes called the border states—

that had yet to decide whether to join the Confederacy.

On April 12, 1861, however, South Carolina troops at-

tacked Fort Sumter, a U.S. outpost located in the harbor of

Charleston, South Carolina. A day later, the Federal troops sta-

tioned at Fort Sumter were forced to surrender, and Lincoln

prepared for war. He promptly proclaimed that the seceding

states were in “a state of insurrection” and vowed to drag the

states of the newly born Confederacy back into the Union. Lin-

69

5

1861: Creation

of the Confederacy

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 69

spite all the pre-election warnings that

the South had delivered, many North-

erners never really believed that their

Southern neighbors might actually de-

cide to leave the Union.

When it became apparent that

the slave states of the Deep South were

willing to make good on their threat,

however, several lawmakers scrambled

to bring them back into the fold. Polit-

ical leaders in Virginia organized a

peace convention in which representa-

tives from twenty-one states tried—but

failed—to come up with a compromise

that would satisfy both sides. President

James Buchanan (1791–1868) also

made some half-hearted attempts to

repair the damage that had been done.

But Buchanan, a Democrat, blamed

Lincoln and the Republicans for the

crisis. After all, the Republicans had

been the ones taking a hard line

against slavery. The Southern states

only planned to secede because they

felt that Lincoln could not possibly

represent their interests as president.

In the end, the outgoing president

seemed willing to leave the messy situ-

ation to Lincoln, who was scheduled

to take over the presidency after his in-

auguration on March 4, 1861.

The most serious proposal to

restore the Union was crafted by a Ken-

tucky lawmaker named John Critten-

den (1787–1863). A senator from one

of several mid-South states that had

not yet decided whether to stay with

the Union or secede, Crittenden called

for a series of compromises on a wide

range of issues. The major elements of

his proposal, however, were two pro-

coln’s call to arms was warmly received

in the North, but it also convinced four

important states—Virginia, North Car-

olina, Tennessee, and Arkansas—to

leave the United States and join the

Confederate States of America.

The Crittenden Compromise

In the days and weeks imme-

diately following the secession of

South Carolina and six other Southern

states, the people living in America’s

Northern states reacted with a mixture

of anger, confusion, and surprise. De-

American Civil War: Almanac70

Words to Know

Confederacy eleven Southern states that

seceded from the United States in

1860 and 1861

Federal national or central government;

also refers to the North or Union, as

opposed to the South or Confederacy

Rebel Confederate; often used as a name

for Confederate soldiers

Secession the formal withdrawal of

eleven Southern states from the Union

in 1860–61

States’ rights the belief that each state

has the right to decide how to handle

various issues for itself without interfer-

ence from the national government

Union Northern states that remained loyal

to the United States during the Civil

War

Civil War Almanac MB 10/7/03 4:01 PM Page 70