Hess Earl J. Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War: The Eastern Campaigns, 1861-1864

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Conclusion

B

y the time Plymouth fell, the armies in the East were on

the eve of the Overland campaign and its intensive use

of field fortifications. The preceding campaigns from

Big Bethel to Plymouth were in one sense a preparation

for the habitual use of fieldworks in 1864–65. Com-

manders on many levels relied on breastworks, earthworks, or preexisting

features on the battlefield during almost every significant engagement from

1861 through 1864. There was a definite trend toward greater reliance on

fortifications, but it was not steady or inevitable.

The evolution of trench warfare was centered, in part, on the problem of

balancing the desire for offensive action with the need for assuming the de-

fensive. If commanders wanted to take the tactical offensive, they often re-

fused to dig in. Entrenching was, by definition, a sign that the commander

wanted to hold his position and fight a defensive battle. Unless they were spe-

cifically designed to maintain one position while the commander attacked

from another, trenches locked soldiers into a static defensive mode. Often, if

the commander were undecided, he would refrain from entrenching in order

to keep open all his tactical options until the last minute.

There was an ebb and flow in the growing reliance on field fortifications

in the eastern campaigns. They were used from the beginning but did not

necessarily play a decisive role in the outcome of either campaigns or battles.

They were often used right after an engagement rather than before or during

it. One can see many examples of this, especially after First Manassas and

Fredericksburg, where the shock of combat led to a greater desire for cover

in case battle was offered again quickly.

The Peninsula campaign saw a great deal of digging by both sides. Mc-

Clellan recognized that the use of earthworks could help him achieve strate-

gic results while lessening casualties. The Confederates relied on strong

earthworks to delay him during his advance up the Peninsula. Lee also relied

on extensive fortifications as a preparation for his offensive against Mc-

Clellan in late June.

Ironically, the success of the Seven Days made the average Confederate

soldier, and Lee himself, less appreciative of earthworks. Their offensive

Conclusion 309

victory at Second Manassas increased their disdain for field fortifications,

even though Jackson’s men barely hung on while defending the unfinished

railroad grade, which was an inadequate substitute for a fieldwork. The

result of Antietam tended to prove that earthworks did have value for an

outnumbered army defending an open position, and several of Lee’s units

took it upon themselves, especially the artillery, to dig in and repel Burn-

side’s frontal attacks at Fredericksburg.

The tendency to rely on earthworks deepened at Chancellorsville, which

became a pivot point in the development of field fortifications in the East.

The Federals and Confederates used fieldworks at almost every turn in the

flow of events. Hooker dug in as soon as he reached the crossroads, and Lee

ordered his men to dig in on the eve of battle for the first time in the war.

Hooker’s men constructed heavy defenses to protect their bridgehead and

line of retreat. Gettysburg represented a temporary reversion to the heady

days of the summer and fall of 1862, when Lee’s men were convinced that

nothing the Yankees would dig could stop them. Rather like the aftermath of

Antietam, the post-Gettysburg period saw a reversion to the tendency to take

fieldworks seriously. Lee’s men fully accepted them at Mine Run, which

became the first instance in the eastern campaigns where fieldworks altered

the tactical course of a campaign. The stage was effectively set for the Over-

land drive to Richmond in May 1864.

The Overland drive was a watershed in the use of fieldworks during the

Civil War, with every phase of the campaign from the Wilderness to Pe-

tersburg seeing employment of large-scale defensive systems. In contrast,

the use of fieldworks from Big Bethel to Plymouth was more modest. Fifty-

seven battles and campaigns are discussed in this book; field fortifications

were employed in 47 percent, and 43 percent were open field engagements.

In addition, semipermanent works were involved in 22 percent of these

encounters, permanent works were involved in only .03 percent, and soldiers

used preexisting terrain features for defensive purposes in 12 percent. Siege

operations were scarcely represented in the eastern campaigns of 1861–64,

with siege works employed in three operations and mining in none.

Even if the first half of the war in the East pales in comparison with the

campaigns of 1864–65 in the employment of fortifications, these early en-

gagements in Virginia nevertheless saw more use of field fortifications than

is evident in American warfare prior to 1861. A total of 108 major battles and

campaigns of the French and Indian War, the War of Independence, the War

of 1812, and the Mexican War were surveyed. Fieldworks were employed in

31 percent, and 30 percent were open field engagements. Semipermanent

works were involved in 26 percent, permanent works were involved in 12 per-

310 Conclusion

cent, and soldiers used existing features for defensive purposes in 9 per-

cent of the engagements. Siege operations were more prominent, with siege

works employed in 12 percent of the operations and mining taking place in

3 percent.

These percentages for pre–Civil War American conflicts are probably sim-

ilar to those for the use of field fortifications in Europe. From the early

sixteenth century, when fieldworks first appear in modern European war-

fare, until the Crimean War of 1854–55, field fortifications were used occa-

sionally and usually in limited ways. The Sebastopol campaign in the latter

conflict presaged Civil War operations such as Petersburg in its heavy re-

liance on fieldworks. The eastern campaigns of the Civil War from 1861 to

1864 saw a significant rise in the use of fortifications, and this period was,

therefore, a transition phase to their increasing use after 1865. In fact, the

half-century from the Civil War to World War I witnessed more attention by

military engineers to the subject, and the Western Front of 1914–18 was the

culmination of this trend, producing the most extensive and sophisticated

field fortification systems ever constructed in history.

∞

Exactly where the tendency to entrench originated in the American Civil

War has been a source of controversy. Early twentieth-century military au-

thors argued that the common soldier was the wellspring of it. While men

who used fieldworks were denigrated as ‘‘dirt-diggers’’ during the early part

of the war, the latter part of the conflict saw the widespread use of fortifica-

tions because ordinary soldiers had a change of heart. ‘‘Great necessity and

the stern experience of war drove erroneous notions from the heads of the

combatants,’’ wrote O. E. Hunt. ‘‘It was the good common sense of the troops

that led them to understand the value of even slight protection. The high

intelligence of the individual American soldier made it a simple matter for

him to grasp this fundamental truth of his own accord.’’ Other commentators

noted the ‘‘education and intuition of the American soldier’’ as keys to his

ability to understand the need for fortifications, and they cited soldiers’

‘‘inventive genius’’ as the tool that allowed them to improvise design fea-

tures. Arthur L. Wagner even made the unfounded assertion that troops

defended works they made for themselves more stubbornly than they de-

fended works that had been built for them.

≤

Edward Hagerman has more recently argued against the view that ordi-

nary soldiers commonly initiated entrenchment on the battlefield. He be-

lieves that since fortifying a line was a big project, the decision to do so must

have been made on a relatively high level of command, at least as high as the

division. Hagerman also asserts that most of the digging was done by engi-

neer and pioneer troops.

≥

Conclusion 311

The truth lies somewhere between these two views. It is wrong to assume

that privates routinely took it upon themselves to dig in; instructions to do so

must have come from an officer, but it most likely was a regimental, brigade,

or division officer. There is no evidence that corps or army leaders were

routinely responsible for the field fortifications dug in the battles of the

eastern theater during the first half of the war, but it is true that common

soldiers did initiate some of them without orders from their officers. The

problem in proving any point on this issue is that orders to dig in would likely

be verbal rather than written, and one must judge by circumstantial evi-

dence. By and large, the early twentieth-century writers were closer to the

truth than Hagerman. Even if fortifying was not always initiated by the rank

and file, their increasing willingness to dig in signifies a recognition that it

was not just necessary but desirable to do so. One can be more definite about

who did the digging: the vast majority of it was done by the infantry troops.

There were not enough engineer troops available, and Confederate authori-

ties used slave and free black laborers only on a few large semipermanent

defense systems.

∂

The role of the rifle musket has also been a prominent theme in previous

literature on field fortifications in the Civil War. Postwar writers were fasci-

nated with the new weaponry, and they wanted to divine its impact on late

nineteenth-century tactics. In the process, they had a strong tendency to

emphasize its impact on Civil War tactics as well, ignoring the fact that the

rifle musket of the 1860s was still a single-shot muzzle loader. They over-

looked the idea that rapidity of fire might be more important in fostering

changes in tactics than the presence of rifling in the barrel. The rifle musket

of the Civil War could not be loaded any faster than a smoothbore. Its only

advantage over the older weapon was a range that was about three times

longer, but Civil War combat was usually fought at short ranges, similar to

those of previous conflicts. In other words, although armed with rifle mus-

kets, Civil War armies continued to fire at ranges generally consistent with

the use of smoothbore muskets.

∑

Yet most modern historians have continued to assume that the rifle mus-

ket was the key factor that led to the widespread use of field fortifications.

Hagerman has written that it was essential in driving the shift ‘‘from the

primacy of the frontal assault to fortified field positions.’’ Assumptions about

the impact of the rifle musket on Civil War military operations have been

questioned by Paddy Griffith. The role of the weapon has been exaggerated;

the rifle musket did not foster the tendency to dig in by the latter part of the

Civil War. The argument has always been made that the armies were fully

armed with rifles by early 1864; since the widespread use of field forti-

312 Conclusion

fications began then, most commentators have connected the two as cause

and effect.

∏

The widespread use of fieldworks was the result of continuous contact

between opposing armies. Even during the first half of the war, when most

infantrymen had smoothbores, lots of digging was done. The fact that en-

trenching often took place right after a battle indicates that the shock of com-

bat affected the minds of commanders and men alike. They naturally wanted

to find protection. Long periods of peace between battles and the offensive

victories of Lee’s men in the Seven Days and Second Manassas tended to

suppress these feelings temporarily, but they resurfaced with Fredericksburg

and subsequent battles. When the armies remained within musket range of

each other for several days, officers and men indulged their desire for protec-

tion by digging elaborate fieldworks. Proximity to the enemy and exposure to

danger were key factors driving the use of field fortifications.

There was also a slow development toward a more sophisticated form of

trench defense during the eastern campaigns of 1861–64. Whenever possible,

engineer officers laid out lines and specified design details. In most cases, the

works that resulted tended to be straight, simple, and uniform. But in cases

where the design details were left up to commanders of infantry units or the

rank and file, one sees innovative and quirky features. Hooker’s fortified

bridgehead at Chancellorsville is the best early example of this phenomenon.

The more often fieldworks were constructed, the less control military engi-

neers had over the details, and the more one can see the impromptu genius of

ordinary officers and men in devising details that suited their tastes.

π

One example of this is the use of headlogs as an added protection. The

first completely documented use of headlogs appears in May 1863. At least a

few Twelfth Corps regiments used them on Hooker’s fortified bridgehead at

Chancellorsville. The same type of headlog was utilized by the Twelfth Corps

on Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg and much more extensively by both armies in

1864. The men simply placed a log lengthwise atop the parapet and raised it

a few inches by using blocks. Federal troops in the siege of Vicksburg devised

a different kind of headlog about the same time. It was made of two logs with

loopholes cut halfway into each log and flattened sides laid together. When

completed, a full loophole was formed. These took time and energy to make,

and they resembled the loopholes in the wooden stockades of frontier forts

and in Civil War blockhouses. The headlogs at Vicksburg were designed to be

used by sharpshooters during a lengthy siege, while the headlogs at Chancel-

lorsville and Gettysburg were designed to be erected quickly and used tem-

porarily by an entire line of battle. Col. John T. Wilder claimed in a postwar

article that his men used headlogs at Munfordville, Kentucky, during Bragg’s

Conclusion 313

invasion of that state in September 1862, but the evidence is inconclusive.

Whenever the first headlogs were used, however, the fact remains that there

was a clear trend toward making earthwork defenses stronger through inno-

vation by individuals and small units by the middle of 1863 in both theaters

of war.

∫

The tendency to dig in within striking distance of the enemy, called hasty

entrenching by postwar military writers, was a true innovation of the Civil

War. Field fortifications were used in many previous conflicts in both North

America and Europe, but they were usually prepared before battle was immi-

nent. True hasty fortifications were constructed under pressure, often liter-

ally under fire. I am not aware of any examples in American or European

warfare before 1861.

The battle of Gaines’s Mill was the first engagement during which either

army in the East dug hasty works, ‘‘constructed on the spur of the moment by

troops just deployed and waiting the hostile advance,’’ in the words of John-

son and Hartshorn in the early twentieth century. Other examples included

many of the works dug during the Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and

Gettysburg campaigns and, of course, Mine Run. They would come to be the

most common form of entrenchment in the brutal Overland campaign and

throughout many phases of the Petersburg campaign as well. Arthur L. Wag-

ner, a prominent military writer of the early twentieth century, noted that

the use of hasty entrenchments ‘‘constituted the most marked characteristic

of the rebellion.’’

Ω

Finally, the terms and conditions defining a field campaign were being

transformed in the Civil War, and much of that redefinition was taking place

in the East during the campaigns of 1861–64. Field campaigns sometimes

took on some of the attributes of a siege, as at Yorktown and Suffolk. There

were classic sieges in the Civil War at Vicksburg and Port Hudson and in

the reduction of Battery Wagner on Morris Island, their character hardly

changed from past experiences in American and European history. But the

size of field armies and a willingness to experiment with certain elements of

siegecraft in static confrontations were marked features of warfare from the

Crimea to World War I.

Likewise, the terminology of field operations became blurred in the Civil

War. It was a peculiarly American, even a peculiarly Civil War, phenomenon

to call any static confrontation in field campaigning a siege. This did not

happen in American wars before 1861 or after 1865 and was rare in European

warfare, too. The Civil War was fought mostly by civilian soldiers who were

not overly careful in their use of terminology.

Whether to fight, retreat, or dig in: these were questions a Civil War field

314 Conclusion

commander had to answer, often under great duress and with woefully

inadequate information. Dennis Hart Mahan sought to guide future Ameri-

can commanders with his doctrine on the use of field fortifications as of-

fensive tools. With volunteer soldiers, poorly trained but highly motivated,

earthworks could be used to hold a position more effectively. Even a green

soldier can steady his nerves while crouched behind a parapet. But Mahan

was influenced by the French example to urge the offensive also, and he

taught that fieldworks could aid the attack as well as strengthen the defense.

It is always difficult to assess the impact of a book or an idea on the

practice of everyday life. Hagerman has argued that McClellan was a firm

disciple of Mahan, that the professor had the biggest impact on the opera-

tions of the Army of the Potomac. The best graduates of West Point and those

who adhered most stringently to the institutional model of the academy

tended to find their way to the ranks of that army. One can argue that

McClellan’s Peninsula campaign was an example of putting Mahan’s theory

of the defensive-offensive to the test, and it worked until Lee took command

and decided to attack in the Seven Days.

∞≠

It is doubtful, however, that other field commanders in the eastern cam-

paigns of the first half of the war thought a great deal about Mahan’s theory

or pored over his writings or mused on his lectures delivered on the banks of

the Hudson River. Field commanders usually thought they had to be on

either the defensive or the offensive and then decide whether or not to dig in.

A useful lesson learned by early 1864, through hard experience rather than

reading, was that the two were not mutually exclusive. Commanders did not

have to give up the offensive when their men dug fieldworks. The reliance on

earthworks certainly did increase the power of the defense, but it did not

necessarily create tactical stalemate. If commanders used fieldworks the

right way, they could add offensive power to their armies. The key was not to

butt one’s head against strong defensive works but to outflank them while

holding the enemy’s attention with equally strong earthworks in their front.

Grant would use this strategy as the only feasible way to pry Lee’s tough

army out of its long trench line at Petersburg.

Civil War officers on all levels of command had to learn how to incorpo-

rate the use of fieldworks into their repertory of skills as a soldier. To ignore

the value of trenches was to deny their men a significant element in the array

of advantages every commander seeks to accumulate in the deadly contest of

war. The eastern armies, North and South, came through hard experience to

fit themselves technically and mentally for their use of fieldworks in the

Overland campaign and at Petersburg by the time Grant took command of all

Union armies in March 1864.

Appendix 1

The Design and Construction of

Field Fortifications at Yorktown

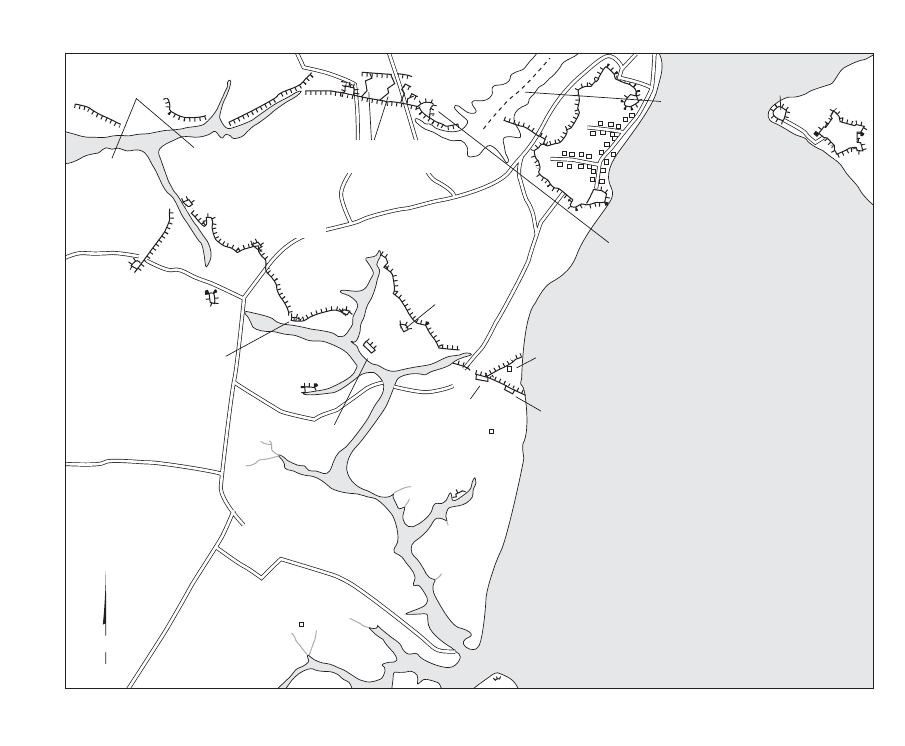

The works at Yorktown were the most significant field fortifications of the eastern

campaigns before the battle of Chancellorsville. Complex and strong, they call into

question the previously held idea that reliance on fieldworks started in 1864. Large

portions of them are well preserved, although the Confederate remnants are more

easily accessible than the Union remnants.

Federal Works

McClellan’s engineer officers conducted their preliminary survey of the Confed-

erate line on April 6–12, while Barnard chose the site for the engineer and artillery

depots. He also scouted the ravines and the road system to the rear of the proposed

Union line. The heavy artillery emplacements received first attention. Batteries No.

1 and 2 were started on April 17 and essentially were completed in three days. No. 3

was begun, and sites were selected for Nos. 4, 5, 6, and 7. By April 22 at least four

heavy artillery works were ready for guns, and No. 3 and No. 6 already had been

armed with 20-pounder Parrotts and 10-inch seacoast mortars, hauled to the works

by 100 horses.

∞

Eventually fourteen heavy batteries, five redoubts, and an unknown number of

emplacements for field guns were constructed by McClellan’s men. Battery No. 1,

near the York River opposite the heaviest Confederate gun emplacements at York-

town, consisted of a layer of logs with a layer of gabions on top, then a thick layer of

sandbags topped the parapet and formed embrasures for the guns. Long, thick

traverses were made of the same material as the parapet. The emplacement was

located in the orchard of the Farinholt homestead, and the large frame house, just

to the rear of the guns, made a superb observation post.

≤

Many engineers and infantrymen were impressed with the construction of Bat-

tery No. 4 because it was placed on the bank of Wormley’s Creek. Capt. Wesley

Brainerd and a party of the 50th New York Engineers cut the emplacement into the

sloping bank, throwing dirt into the creek until they had room for as many as ten 13-

inch mortars. The 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery was responsible for placing and

manning them. The entire floor of the emplacement was leveled, and a wooden

platform was built for each mortar. The undulating creek bank was five to twenty

Yorktown

Moore’s

N

Y

o

r

k

t

o

w

n

R

o

a

d

McClellan’s

Headquarters

Battery No. 5

Battery

No. 2

Battery No. 9

Battery No. 14

Red

Redoubt

Redoubt A

Redoubt D

Communication trenches

between rear and forward lines

Battery No. 6

Battery

No. 12

Battery No. 10

Battery

No. 4

White Redoubt

(Fort Magruder)

Redoubt B

Battery No. 1 (at Farinholt House)

Battery No. 3

Battery No. 13

Battery

No. 11

Water

battery

Redoubt C

YORK

RIVER

W

o

r

m

l

e

y

’

s

C

r

e

e

k

Marshy ravine (headwaters

of Warwick River)

Ravine

(Beaverdam

Creek)

Gloucester

Point

Union and Confederate Works, East End of Warwick Line, Yorktown, April 1862

Appendix 1 317

Federal Battery No. 4, Yorktown. This mortar battery was uniquely dug into the bank

of Wormley’s Creek, and access to it was gained by a footbridge over the stream, seen

on the far left of this stereoscopic view. Ordnance was shipped to the site in the barge on

the right. (Library of Congress)

feet above water. A small ravine that drained into the creek exposed the gunners to

Rebel view, so the engineers built a stockade across it. The battery was accessible

only from the rear, across the creek, so the engineers spanned the stream with a

footbridge. The gunners hauled in their weapons and supplies by barges, which

were pushed up the stream and anchored just behind the battery.

≥

Emplacements for field batteries on the center of the Union line received much

less attention. Remnants of a position for eight guns, divided into two four-gun

emplacements, are located opposite the Rebel position at Dam No. 1. It is the right

wing of a work that curved around the Garrow house, which was burned at the

start of the confrontation at Yorktown. The two emplacements have traverses and a

continuous platform for all four guns on the natural level of the earth. They are also

flanked by a much thinner infantry parapet.

∂

McClellan’s artillery chief, Brig. Gen. William F. Barry, recommended that infan-

try and field artillery be deployed near the heavy guns. He believed No. 3 and No. 6

were ‘‘particularly exposed to sorties of the enemy.’’ Apparently no one had planned

to connect the heavy gun emplacements with curtains or even to construct flank

protection for them, but Barry’s recommendation spurred efforts to connect the

batteries with infantry lines on April 25. First, a line was started between Batteries

No. 2 and 3, and another was started from the Yorktown Road toward No. 5. That

night the line between 2 and 3 was quickly finished across open, exposed ground.

This section was dug four feet deep and six feet wide. Also on the night of April 25, a

line was dug from Redoubt C, which lay forward of the heavy batteries, toward the

southeast to cover the approaches to No. 9 and No. 12. This line was later completed

all the way to the York River. From this latter section, a branch was run diagonally

to a point 200 yards farther upstream than the original end of the line. Completed