Heine Bernd, Nurse Derek. A Linguistic Geography of Africa

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

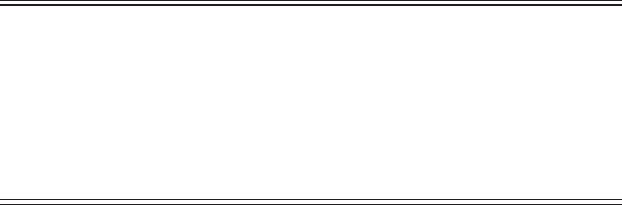

Table 6.6 Features of the Tanzanian Rift Valley area and membership index of individual languages

PIRQ AL BU San-

dawe

Hadza F32 F31 F33/

34

Datoo-

ga

Swa-

hili

Maasai Oromo

P1 lateral fricative /l/ þþþþþ

P2 ejective obstruents þþþþþ þ

P3 contrast of /k/

vs. /q/

þþþþþþ þþ

P4 no voiced

fricatives

þþþþþ þþ

G1 preverbal clitic

complex

þþþþþþþ þ

G2 verbal plurality þþþþ??? ?þ

G3 applicative þþþþ??? ?þþ

G4 ventive þþþþþþþ þþþþ

G5 2 past tenses þþþþþ þþþ

G6 1 future þþþþ þþþ

G7 subjunctive -ee þþþþþþ þþ

G8 laa for irrealis þþ

G9 infinitive þ

auxiliary order

þþþ?? þþ

G10 head initial

position in NPs

þþþþþþþ þþþþþ

G11 prepositions þþþþþþ þþþþ

G12 SVO þþþþþ þþþ

G13 body-part nouns

> prepositions

þþþ???? ?þþ

G14 polysemy of ‘in’

and ‘under’

þ???? ?þ?

G15 ‘belly’ for

emotional concepts

þþ??? ?þ?

Membership index on

the basis of all

features

16/20

¼ 80%

16/20

¼ 80%

17/20

¼ 85%

11/18

¼ 61%

10/15

¼ 67%

9/13

¼ 69%

8/13

¼ 62%

8/13

¼ 62%

15/20

¼ 75%

7/20

¼ 35%

6/18

¼ 33%

4/20

¼ 20%

Membership index on

the basis of the

bundle of 7 core

features

6/7 ¼

86%

6/7 ¼

86%

7/7 ¼

100%

5/7 ¼

71%

5/6 ¼

83%

6/7 ¼

86%

5/6 ¼

83%

4/6 ¼

66%

7/7 ¼

100%

4/7 ¼

57%

2/7 ¼

29%

2/7 ¼

29%

(G6, source: East African Bantu); and finally head-initial NPs (G10, source

East African Bantu or Pre-Datooga). This constitutes a strong bundle of fea-

tures because all of them involve changes and are specific enough to be reliably

attributed to contact and not to universal tendencies or chance. In spite of the

locality and partial typological countercurrency of most of these develop-

ments, some broad general trends are observed: transition to head initial order

(G10, G11, G12; but countercurrent: G9), and the transition to head marking of

syntactic relations (G1, G2, G4).

We calculated the degree of similarity by establishing for every member of

the contact zone, and on the basis of the number of shared areal features, an

index that indicates the relative centrality or peripherality of the languages in

quest ion (see table 6B in the append ix ). We added Swah ili (Bant u), Maas ai

(Nilotic), and Oromo (Cushitic) as control languages from outside our contact

zone. This index ranges from a minimum of 61 percent (Sandawe) and 62

percent (Nilyamba, Rangi, Mbugwe) up to a maximum of 85 percent (Bur-

unge). The three control languages confirm the validity of the language area

with indices of 20 percent (Oromo), 33 percent (Maasai), and 35 percent

(Swahili). The West Rift languages display most of the area l features. The

lacunae in the documentation of Hadza, Isansu, and Nilyamba still pose a

serious problem, causing some distortion of the results.

With the exception of features (G7) and (G8), which constitute direct

transfer of morphemes, all index features are isomorphisms, i.e. convergences

in syntactic structures and semantic categories where at least one member of

the contact zone innovated structures or categories on the basis of an external

model, using internal mor phological material. This points to contact scenarios

which are characterized by multilingualism and massive language shift

(Thomason & Kaufman 1988: 95f.) within settings of shifting political, eco-

nomical, and cultural dominance.

We were able to identify the ultimate source of most features discussed

here.

16

The list in (35) bri ngs together in one display the trends of contact-

induced change according to sources.

(35) Source-wise overview of contact-induced innovations in the Tanzanian

Rift Valley:

Pre-Sandawe

> PWR, Pre-Datooga

verbal plurality (G2)

Proto-West Rift

> Pre-F31/32, Pre-Datooga

preverbal clitic complex (G1)

contrast of two voiceless dorsal obstruents (P3)

Roland Kießling et al.224

> Pre-F33/34

infinitive þ auxiliary (G9) [< Proto-Iraqw/Gorwaa]

East African Bantu

> Proto-West Rift

two pasts (G 5)

subjunctive -ee (G7)?

> Proto-Southern West Rift / Pre-Burunge

future (G6)

SVO (G12)

> Pre-Datooga

future (G6)

Pre-Datooga

> Proto-West Rift, Sandawe

head-marking the direction of a process in relation to a deictic center (G3)

> Proto-Iraqw/Gorwaa

grammaticalization: body-part nouns > prepositions (G13)

link of the spatial concepts ‘in’ and ‘under’ (bovimorphic model) (G14)

metonymic use of ‘belly’ in the expression of emotional concepts (G15)

In historical terms, this results in a complex picture of mutual linguistic con-

tacts of varying intensity at several points in time, the rough lines of which are

summarized as follows:

(i) Spread of structural features from a West Rift source to some Bantu F

languages and to Datooga. This includes the emergence and rise of a

preverbal clitic complex (G1) in Nyaturu and Datooga, the development

of a phonemic opposition of two voiceless dorsal obstruents (P3) in

Nyaturu and Datooga. These facts point to a scenario of language shift

from Proto-West Rift or one of its predecessors to Pre-Datooga and Pre-

Nyaturu, where the shifting bilinguals imported these West Rift features

into the Bantu and Niloti c target languages. The emergence of head-final

order of infinitive plus auxiliary (G9) in some periphrastic tenses in

Mbugwe and Rangi happened at a later stage under influence of the

individual West Rift languages.

(ii) Steady Bantuization of Proto-West Rift, Proto-Southern West Rift, then

Burunge (Alagwa) and a marginal Bantuization of Pre-Datooga. The

Bantuization of Pre-Datooga is reflected in the innovation of a synthetic

future tense (G6) and possibly in the reduction of a former ten-vowel

system to seven vowels (P5). The Bantu imprint on Proto-West Rift is

represented by the innovation of two synthetic tenses with past reference

(G5) and the retention of a subjunctive in -ee (G7). Possibly the general

trend in West Rift towards head-initial order within the NP (G10) must

The Tanzanian Rift Valley area 225

also be attribut ed to Bantu influence. In a subgroup of West Rift, in

Proto-Southern West Rift, and later on in Burunge, the Bantu influence

intensified considerably, as manifest in the change of basic word order to

SVO (G12), and the innovation of three tenses with future reference in

Burunge (G6). Evidence of Bantuization has also been detected in the

progressive reanalysis of the nominal gender system of Proto-Southern

West Rift on a semantic basis through the increasing affinity of neuter

gender to the semantic category of plural, accomplished by reanalysis of

neuters with singular reference as masculine and by reanalysis of

masculine and feminine plural markers as neuter and through a clearer

convergence of grammatical gender and sex, accomplished by the

elaboration of paired singulatives, masculine and feminine, for animal

referents.

(iii) Diffusion of structural and semantic features from Pre-Datooga into

Proto-West Rift and, later on a broader scale, into the Iraqw/Gorwaa

subgroup of West Rift. These include the introduction of a morpho-

logical expression of the direction of event or action in relation to a

deictic center (G3) in Proto-West Rift, the grammaticalization of body-

part nouns to prepositions (G13) with concomitant linking of the spatial

concepts ‘in’ and ‘under’ following the bov imorphic model (G14) and

the metonym ic use of the body-part noun ‘belly’ for the experiencer in

expressing emotional concepts (G15) in Proto-Iraqw/Gorwaa. This

bundle of features must b e a semanto-syntactic imprint of Datooga on

Proto-West Rift, later Proto-Iraqw/Gorwaa, left by shifting Pre-Datooga

bilinguals. The sociohistorical background of the latter line is discussed

in detail in Kießling (1998b).

(iv) Only one feature has been attributed to a Pre-Sandawe source, namely

verbal plurality (G2), which must have spread to Proto-West Rift and to

Datooga by mediation of shifting Pre-Sandawe speakers , generalizing

semantic concepts of derivational markers pre-existent in those lan-

guages for inflectional purposes.

(v) In addition, there are several features, exclusively phonological ones

(P1, P2, P4), that tie up West Rift with Sandawe and Hadza and which

seem to reflect an ancient contact predating all the other contacts

identified so far, since it is not obvious in which direction the shared

features have been transferred, if transfer has actually happened at all.

Some of these features point beyond the Tanzanian Rift Valley area , e.g. the

lateral fricative (P1). On the Southern Nilotic side, the only member in the area,

Datooga, deviates, since it does not have a lateral fricative. Closely related

Omotik, however, has a later al fricative and on this basis it has been recon-

structed for Proto-Southern Nilotic (Rottland 1982: 233). If this was a Southern

Roland Kießling et al.226

Nilotic innovation within Nilotic inspired by Southern Cushitic influence, it

must have taken place far north o f the Tanzanian Rift Valley area, at the time of

the Proto-Southern Nilotic period. This suggests that the Tanzanian Rift Valley

might be a secondary contact zone and area of retreat where linguistic groups

from genetically different backgrounds came together at various points in time,

converging in various aspects of their structures, while part of these con-

vergences might also be traced back to primary contacts at places outside the

contemporary scene of cont act. This could also mean that the Tanzanian Rift

Valley area is a residual zone resulting from a contraction of a formerly much

larger area of contact. The Tanzanian Rift Valley area has been coined “das

abflusslose Gebiet” in the early German literature (e.g Luschan 1898 ),

denoting the fact that no rivers stream out of the area. Also linguistically our

sprachbund acts like an abflussloses Gebiet.

The Tanzanian Rift Valley area 227

7

Ethiopia

Joachim Crass and Ronny Meyer

7.1 Introduction

The Ethiopian Linguistic Area (ELA) is the most famous linguistic area in

Africa. It is the only linguistic area of this continent mentioned and (some-

times) discussed to a certain extent in general works dealing with language

contact and areal linguistics (e.g. Masica 1976; Thomason 2001b; Thomason

& Kaufman 1988). Most scholars dealing with Ethiopian languages refer to

this area as the ‘‘Ethiopian Language Area’’ (Ferguson 1970, 1976; Sasse

1986; Hayward 1991; Zaborski 1991, 2003; Tosco 1994b; Crass 2002). This

term, however, is problematic in several respects:

(a) The English translation of what is called in German Sprachbund is lin-

guistic area, convergence area,ordiffusion area (Campbell 1994: 1471).

The term linguistic area is used by most of the authors dealing with such

areas (e.g. Masica 1976 ; several papers written by Emeneau, collected in

Dil 1980; Thomason 2001b).

(b) At least partly, the area includes Eritrea, which was a province of Ethiopia

until it became an independent state in 1993.

(c) A certain numb er of features are found beyond Ethiopia and Eritrea in

languages spoken in the neighbori ng countries Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan,

and even beyond.

Some scholars have taken these facts into account, at least to some exte nt.

Hayward (2000b: 623) uses the term ‘‘Ethio-Eritrean Sprac hbund’’ and

Zaborski (2003) proposes ‘‘North East African Language Macro-Area.’’

Despite the fact ‘‘that the overlap [of features] into neighboring regions is

minimal’’, Bender (n.d.: 4) stresses that ‘‘[n]ow we must modi fy it to ‘Ethiopi a-

Eritrean Area,’ in view of recent political history.’’ In the present chapter, the

term Ethiopian linguistic area (ELA) is used in order to account for the fact that

language area is not the commonly used term in areal linguistics and that the

core of the area is Ethiopia.

According to Grimes (2000: 109), eighty-two languages are spoken in Ethi-

opia. Most of them belong to three language families of the Afroasiatic phylum,

228

namely Semitic, Cushitic, and Omotic. A number of languages in the west and

southwest belong to different families of the Nilo-Saharan phylum and are

therefore not genetically related to the languages of the Afroasiatic phylum.

According to a widely accepted view, Semitic-speaking peoples arrived in

the Horn of Africa at the end of the first millenni um BC by crossing the Red

Sea after having left their homeland on the Arabian peninsula. They migrated

into the area of today’s Ethiopia and Eritrea and underwent extensive linguistic

and extralinguistic influence by Cushitic-speaking peoples (Ullendorff 1955 ).

A contradicting view considers Ethiopia to be the original homeland of

Semitic-speaking people (Hudson 1977; Murtonen 1967). This view is based

on the assumption that the linguistic dive rsity among Semitic languages in

Ethiopia is much greater than elsewhere.

7.2 Research history

Leslau (1945, 1952, 1959) and Moreno (1948) describe the influence of

Cushitic languages on Ethio-Se mitic languages. The first to claim the existence

of a linguistic area in ‘‘Ethiopia and the various Somalilands’’ was Greenberg

(1959: 24). He is of the opinion that this area is characterized by ‘‘relatively

complex consonantal systems, including glottalized sounds, absence of tone,

word order of determined followed by determiner, closed syllables, and some

characteristic idioms.’’ According to Heine (1975: 41f.), who deals with word-

order typology, Ethiopia is part of ‘‘probably the largest convergence area in

Africa, stretching in a broad belt from the Lake Chad region in the west to the

Red Sea and the Indian Ocean in the east.’’

Ferguson (1970, 1976) was the first to describe the ELA in more detail.

Ferguson (1976), with an extended database and improv ements and correc-

tions, is still the reference work; it will therefore, be the starting point in our

analysis of features. Ferguson discusses 8 phonologi cal and 18 grammatical

features on the basis of 18 languages, including Arabic and English. He argues

that the ‘‘languages of Ethiopi a constitute a linguistic area in the sense that they

tend to share a number of features which, taken together, distinguish them from

any other geographically defined group of languages in the world’’ (Ferguson

1976: 63f.). He stresses that ‘‘some of these shared features are due to genetic

relationship ... , while others result from the process of reciprocal diffusion

among languages which have been in contact for many centuries.’’

Zaborski (1991: 124) criticizes Ferguson’s selection of languages and fea-

tures. He argues that the languages are ‘‘rather random[ly] selected’’ and that

‘‘most of the alleged areal features are not really areal but of common genetic

origin.’’ Hayward (2000b: 623) is of the opinion that a number of Ferguson’s

features are ‘‘characteristic of most languages of this region’’ of which he

considers five to be ‘‘very widesp read.’’ Some contributions deal with only one

Ethiopia 229

areal feature: Appleyard (1989) discusses relative verbs in focus constructions;

Tosco (1994b) deals with case marking; and Tosco (1996) with extended verb

paradigms in the Gurage-Sidamo subarea, one of the subareas of the ELA

proposed by Zaborski ( 1991).

Tosco (2000b) denies the existence of the ELA because of the genetic

relatedness of Ethio-Semitic and Cushitic languages, the unilateral diffusion

from Cushitic to Ethio-Semitic and the occurrence of features in related lan-

guages, which do not belong to the ELA. Four recent papers, namely Bender

(2003), Crass (2002), Crass and Bisang (2004), and Zaborski (2003) favor the

existence of a linguistic area. Bender (2003) argues against Tosco (2000b)and

tries to extend the ELA by testing a number of Nilo-Saharan languages using a

selection of Ferguson’s features. Crass (2002) discusses two phonological fea-

tures in detail; in Crass and Bisang (2004) the discussion is extended to features

such as word order, converbs, and ideophones verbalized by the verb ‘to say.’

Zaborski (2003) presents the most extended list, including twenty-eight features

which he considers to be valid for a macro-area including Ethiopia, Eritrea,

Djibouti, Somalia, and parts of Sudan, Kenya, and even Tanzania and Uganda.

Finally, Hayward (1991) deals with patterns of lexicalization shared by the three

Ethiopian languages Amharic (Semitic), Oromo (Cushitic), and Gamo (Omotic).

According to Hayward (1991: 140), these lexicalizations reinforce ‘‘the very real

cultural unity of Ethiopia’’ (see also Hayward 2000b).

The ELA is consider ed to be composed of several subareas. Leslau (1952,

1959) describes change in Ethio-Semitic languages induced by contact with

neighboring Highland East Cushitic languages. Sasse ( 1986) deals with the

Sagan area in the southwest of Ethiopia, and Zaborski (1991: 125ff.) gives a list

of seven subareas being composed of ‘‘smaller contact and interference units’’

which he extends to nine by adding a Kenyan and a Ta nzanian subarea

(Zaborski 2003: 64).

7.2.1 Phonological features

Ferguson’s phonological features are listed in table 7.1 .

Ferguson’s li st has been criticized in most of the later publications. Zaborski

(1991: 124, footnote 3) considers only P3 and ‘‘with reservations’’ P2 to be

‘‘really areal.’’ Zaborski (2003: 62) lists four phonological features. Besides P3

and P6, Zaborski argues that ‘‘labialized conson ants are frequent [and that]

some palatalized consonants are innovations.’’ Tosco (2000b: 341ff.) is of the

opinion that P1, P2, P3, and P5 are genetically inherited within Afroasiatic, that

P4, P7, and P8 are restricted to one or two language families, and that P6 is

widespread in both Afroasiatic and Nilo-Saharan. According to Bender (n.d.),

P2 and P6 are typological features, P5 is too limited and P8 ‘‘is vacuous

because consonant clusters are rare.’’ P1, P3, P4, and P7, however, are ‘‘fairly

Joachim Crass and Ronny Meyer230

idiosyncratic and easy to check.’’ Hayward (2000b: 623) explicitly mentions

only one phonological feature, namely P6.

Crass (2002) discusses P3 and P5 in detail. Both features being genetic ally

inherited in Afroasiatic, Crass argues that occurrence (of ejectives) and non-

occurrence (of pharyngeal fricatives) can be considered areal features.

Reconstructions of different stages of proto-languages of Afroasiatic show that

ejectives were lost over the course of time (cf. Crass 2002: 1683ff.). In recent

times, however, ejectives were reimported into most of the languages via

contact. For Proto-Highland East Cushitic, for example, only one ejective is

reconstructed, namely the velar ejective. In most of the modern Highland East

Cushitic languages, however, four ejectives occur as phonemes, namely the

dental, the postalveolar affricate, the velar, and to a smaller extent the labial

ejective (Hudson 1989: 11). In the Agaw languages (Central Cushitic), ejec-

tives occur predominantly in loanwords from Amharic and Tigrinya and their

phonemic status is problematic (cf. Appleyard 1984: 34f.). The reasons for the

non-occurrence of pharyngeal fricatives in most Central Ethiopian languages

are unclear. The non-occurrence may be due to language contact or due to

language-internal change. Tosco (2000b : 343) supports Crass’s idea in briefly

mentioning that the non-occurrence of pharyngeal fricatives ‘‘could identify a

smaller ‘central Ethiopian area’ ... in which pharyngeal consonants are either

dropped or reduced.’’

This short summary shows that the views concerning the phonological

features vary considerably. Only in three cases is there clear agreement among

scholars, namely between Crass and Tosco concerning the non-occurrence (or

loss) of pharyngeal fricatives in Central Ethiopia, between Crass and Zaborski

concerning ejectives, and between Hayward and Zaborski concerning con-

sonant gemination. In several other cases, agreement can be postulated:

Hayward (2000b: 623) mentions that ‘‘Ferguson listed a number of very

obvious linguistic typological features, that were characteristic of most lan-

guages of this region.’’ Bender (2003: 31) considers all features except P5 and

Table 7.1 Phonological features (Ferguson 1976: 65ff.)

P1 /f/ replacing /p/ as the counterpart of /b/

P2 Palatalization of dental consonants as a common grammatical process in at least

one major word class

P3 The occurrence of ejectives (in Ferguson’s terminology: glottalic consonants)

P4 The occurrence of an implosive /d’/

P5 The occurrence of pharyngeal fricatives

P6 The occurrence of consonant gemination

P7 The occurrence of central vowels being shorter in duration than the other vowels

P8 The occurrence of an epenthetic vowel (in Ferguson’s terminology: helping vowel)

Ethiopia 231