Gopalakrishnan K., Birgisson B., Taylor P., Attoh-Okine N.O. (Eds.) Nanotechnology in Civil Infrastructure: A Paradigm Shift

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

K. Gopalakrishnan et al. (Eds.): Nanotechnology in Civil Infrastructure, pp. 175–205.

springerlink.com

© Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2011

Nano-optimized Construction Materials by

Nano-seeding and Crystallization Control

Michael Kutschera, Luc Nicoleau, and Michael Bräu

*

176 M. Kutschera, L. Nicoleau, and M. Bräu

the very beginning. Since the dawn of time, the need to create a shelter, a home,

alongside acquiring food and partnership remains in the top 3 creature priorities.

This inevitably implicates that historically, to create the said shelter or housing,

the best developed technologies that were suitable and affordable during those

times have been used. Starting from wooden shacks, clay cottages, natural stone

dwellings up to brick mansions and concrete buildings there has been a constant

and tremendous development. But it is often not recognized as high-tech due to

the fact that more or less everybody has access and can use the technology on a

very normal basis.

However we will show that modern hydraulic binder systems including cement

and gypsum are on the eve of a technological revolution. Modern possibilities of

engineering and modification on the nanoscale can influence the existing nano-

structure of cementitious systems in a targeted, specific and systematic way.

A start can be made with existing building materials. They can roughly be

sorted into three classes:

• Solid mass natural materials (e.g. stone, wood, straw)

• Pre-processed, manufactured materials (e.g. iron, steel, glass, brick)

• On site reactive materials (e.g. clay, lime mortar, gypsum, cement, concrete)

Each class has its own quality and application area and nearly all buildings are

made of a combination of those materials. From the engineering side, solid mass

natural materials are typically quite cheap but require certain workmanship and

are not easily compatible with modern industrial construction methods or proce-

dures. Here lies the advantage of pre-processed, manufactured materials. They

come in standardized dimensions and can be delivered on a regular basis with

guaranteed quality. Additionally they have some extraordinary material properties

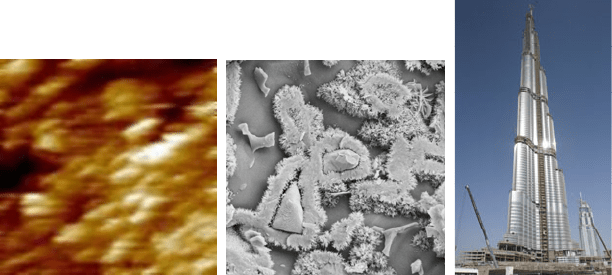

Fig. 1 Bridging the gap of several orders of magnitudes in length scale: Nano-engineering

and nano-modification of hydraulic binder systems. Left: nanoscale calcium silicate hy-

drates on sintered tricalcium silicate surface in a calcium hydroxide solution after 2 hours

observed by atomic force microscopy (particles of 30x60 nm²) [Nicoleau 2004], middle:

microstructure within reacted cement paste (µm…mm), right: Burdsch Chalifa during

construction (m…km). (picture sizes left: 0.4 µm

•0.4 µm, middle: 20 µm•20 µm, right:

~500 m•830 m)

Nano-optimized Construction Materials by Nano-seeding and Crystallization Control 177

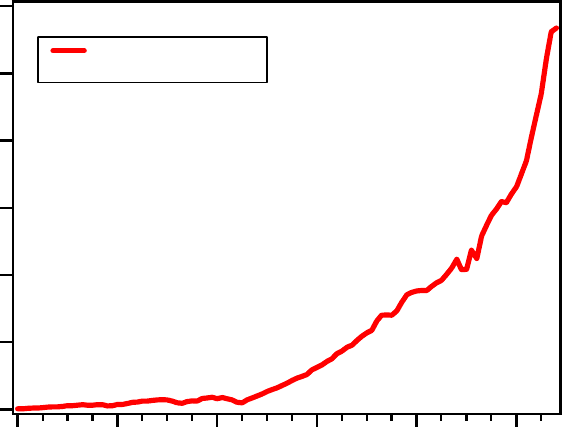

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0

x10

9

200019801960194019201900

Year

global cement usage

(metric tons)

Fig. 2 Dramatic increase of global cement usage during the last century ([U.S. Geological

Survey 2010]).

(like steel or glass). Finally on-site reactive materials fulfill double function. They

are used to bond together other construction materials (like brick) and on the other

hand can be filled into a boarding to form a construction element of any desired

form when hardened.

This classification is not fully distinctive. There are lots of materials which be-

long to multiple categories like e.g. prefabricated concrete parts or clay-straw

composites. Nonetheless the classification is still helpful.

1.1 A Short History of Cementitious Systems

When looking back on the history of construction, gypsum is by far the most an-

cient material. Traces of the use of gypsum go back to 7000 b.c. and there are

clear descriptions dating back to 3000 b.c. when Egyptians burned gypsum in

open-air fires. To produce gypsum, natural calcium sulfate hydrates are thermally

treated (burned) to generate a mixture of calcium sulfate hemi-hydrate and anhy-

drate. The processing itself as well as reaction times and temperatures determine

the resulting composition and subsequent product properties and quality. Modern

production methods focus on low prices (flash calciner, high temperatures, short

residing times) or high quality and robust reactivity (autoclave-type calciner, low-

er controlled temperature profiles, longer burning times).

178 M. Kutschera, L. Nicoleau, and M. Bräu

Proven traces of cement production and usage go back to the Roman age where

the so called Opus Caementicium was used as a recipe for the inside of brick-

faced or solid concrete buildings. The Romans also used aggregates and different

hydraulic binder systems (lime, pozzolans, cement) to form lime mortars, struc-

tural mortars, underwater mortars and concrete [Vitruvius, 25].

Modern cement development started some 200 years ago. In 1817 Louis Vicat a

French engineer invented an artificial cement called white gold. This finding was

superseded in 1824 when Joseph Aspdin who was a master craftsman for masonry

in Leeds (England) filed a patent called “an improvement in the mode of produc-

ing an artificial stone”. This so called ordinary Portland cement (OPC) mainly

consists of calcium silicates with the most prominent modifications tricalcium sili-

cate (Alite) and dicalcium silicate (Belite) among aluminates, ferrites and many

more components and impurities. For Portland cement the production consists of a

calcination (de-carbonization) process in a rotary kiln. Raw materials are among

others limestone and clays. Due to the high temperatures needed for calcination

(approx. 1400°C) optimizing the production with respect to a decreased energy

demand, management of the energy source used as well as use of secondary en-

ergy carriers (e.g. plastic waste or tires) were important tasks in modern cement

production. CO

2

emission is still a major future challenge for cement producers.

From a scientific view it is valid to treat cement and gypsum within one com-

mon scope. In a physico-chemical sense both raw materials dissolve in contact

with water leading to a very high local supersaturation with respect to calcium-

silicate-hydrates or calcium-sulfate-hydrates respectively. This is due to the fact

that hydrated species have a lower solubility when compared to the not hydrated

ones. The following precipitation process is therefore running highly thermody-

namically unbalanced. But also complex kinetics like supply of fresh ions, forma-

tion of critical nuclei and self-passivation play an active role during the hardening

process. In addition both materials undergo some transitions from amorphous pre-

cursors to intermediate and final crystalline structures. A detailed description of

these reactions will be given in chapter 2 for cement and gypsum.

In the view of nano-technology (hardened) cement itself without any modifica-

tions is clearly a nano-material. It has a hierarchical structure ranging from sub-

millimeter dimensions down to nanometer scale. And it is known that a lot of its

material properties strongly depend on the structures and the structure develop-

ment below 100nm [Taylor 1997]. Examples are rheological behavior in liquid

state, shrinkage during hardening as well as the development of the final compres-

sive and flexural strength. Things are not so clear for gypsum. Here the

CaSO

4

·2H

2

O crystals are well in the µm range. On the other hand the mechanical

properties of gypsum depend on the cohesion between these crystallites. This can

be easily seen by the decrease of mechanical strength upon humidity or wetting of

gypsum specimens [Tesarek et al 2004; McGowan 2007]. Theses cohesion forces

again very much depend on Van der Waals forces, inner surface structure match-

ing and roughness on nanometer scale. Therefore cement and gypsum are by na-

ture a nanostructured material with complex hierarchical super and sub-structures.

Nano-optimized Construction Materials by Nano-seeding and Crystallization Control 179

Coarse

Aggregate

Sand

Fine

Aggregate

Fly Ash

Portland Cement

Metacaolin

(Processed)

Processed (Ground)

Mineral Additives

Silica Fume

Nano Silica

Precipitated,

Stabilized Silica

Molecules

C-S-H

Colloids

C-S-H

Gel-Network

10

-9

10

-8

10

-7

10

-6

10

-5

10

-4

10

-3

10

-2

10

-1

Structure Size (m)

10

-2

10

-1

10

0

10

1

10

2

10

3

10

4

10

5

10

6

Specific Surface Area (m

2

/kg)

Conventional Concrete

High Performance Concrete

Nano-engineered / Nano-modified Construction Material

Fig. 3 General view on length scales and surface areas related to construction materials and

additives for construction materials [Sobolev 2006].

1.2 Current Trends in Nano-modification of Cementitious

Systems

In the last decades there has been a continuously increasing trend to modify and

optimize cementitious binders by means of nanotechnology and nanoscale addi-

tives. In a roughly chronological order the following modifications evolved:

• Supramolecular additives

• Nanoscale fillers (inert)

• Functional nano additives which influence hydration and/or structure

development

Supramolecular additives for cement and concrete are known and used since the

mid-1960s. They can act as for example high performance dispersants, rheology

modifier or anti shrinkage agents. All of them act in the liquid pore solution before

the final hardening of the concrete. They modify and partially cover the surfaces

both of the starting materials as well as of the forming hydrate particles. On these

surfaces they control rheological properties of the cement paste by electrostatic,

hydrophobic or steric interactions. They also modify (lower) the surface energies

leading to changes in wetting properties and decreased capillary forces. Typical

chemistries used have sulfonate, carboxylate or amine functionalities (among

many others…).

The development of improved supramolecular additives allowed incorporation to a

certain extent, nanoscale filler particles and materials into cement paste and concrete

mixtures. These fillers are mostly inert meaning that they neither interfere with the hy-

dration process nor do they change the hydration products. Typical examples for those

180 M. Kutschera, L. Nicoleau, and M. Bräu

fillers are micro-silica, nanoscale pyrogenic SiO

2

, Ca(OH)

2

or even TiO

2

particles.

Their main task is to optimize the grain size distribution leading to a highly filled and

compact cement matrix with reduced pores and voids. There has been a noticeable de-

velopment in the mix design using nanoscale fillers. The resulting ultra high perform-

ance concretes (UHPCs) outperform standard concretes with very high compressive

strengths and better flexural strength and increased durability. The use of these UHPCs

is still limited to high performance civil infrastructure applications like bridges, iso-

lated parts or in ocean underwater structures. The UHPC parts are prefabricated and

require novel joining and application techniques (e.g. gluing instead of grouting) [Feh-

ling, Schmidt and Stürwald 2008].

The latest means of nano-modification of cementitious systems are functional

nano additives which influence hydration and/or structure development. Known

systems comprise of nano-tubes or nano-rods (mainly carbon nanotubes [Akkaya

2003; Trettin and Kowald 2005 & Shah 2009]), nanoscale C-S-H particles and na-

noscale gypsum particles. They shall act as internal reinforcement as well as nu-

cleation and crystallization seeds. In the following chapters we will focus on the

latter two means of nano-modifications. In chapter 2 we will discuss the chemical

reactions occurring during hardening of cement and gypsum followed by a short

overview of relevant analytical tools and modeling approaches in chapter 3. Chap-

ter 4 is about nano-modification of the nucleation steps during hydration. Finally

chapter 5 demonstrates a means of influencing and modifying the subsequent crys-

tallization processes on the nanometer scale. Some final concluding remarks will

summarize the contents. We explicitly note that there are numerous hydration

models, modeling techniques as well as characterization methods that are pub-

lished and proven but cannot be repeated due to size and scope limitations. Our

main focus will be the manipulation of the hydration process of cement and gyp-

sum by nano-modification of the nucleation period of those materials.

2 The Hardening of Construction Materials

2.1 Hydration in Ordinary Portland Cement

Concrete is the complex mix of cement powder, sand, gravel, water and admixtures.

It is daily used almost everywhere on earth and allows raising sky-creepers of hun-

dredth meters high. The secret for building such tall and at the same time fragile

structures originates in a structure transformation at the nanometer scale occurring in

cement paste. The changes of this fluid concrete paste to a load-bearing material are

due to cohesion properties of the cement part and to the microstructure evolution

over time. A false belief is to trust that cement is simply drying when it hardens; in

fact it reacts with water (it hydrates) to form new amorphous and crystalline phases.

The pore microstructure changes during the whole cement hydration. This evolution

is a multi-scale development from the nanometer range up to tens of microns and is

the key for the resulting material properties like workability, compressive and flex-

ural strengths, durability, permeability, etc…

The microstructure and its modification with time result from the precipitation

of different hydrates, coming from the reaction of the main anhydrous phases