Gary Nichols. Sedimentology and Stratigraphy(Second Edition)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

was the time between 299 and 251 million years

before present. This is analogous to historians refer-

ring to the time between 1837 and 1901 as ‘the

Victorian period’. Geological time is normally

expressed in millions of years or thousands of years

before present (‘present’ is commonly defined as

1950, although this distinction is not necessary on a

scale of millions of years!). Geological time units are

abstract concepts, they do not exist in any physical

sense.

The abbreviations used for dates are ‘Ma’ for mil-

lions of years before present and ‘ka’ for thousands of

years before present. The time thousands of millions of

years before present is abbreviated to ‘Ga’ (Giga-

years). The North American Stratigraphic Code

(North American Commission on Stratigraphic

Nomenclature 1983) suggests that to express an

interval of time of millions of years in the past abbre-

viations such as ‘my’, ‘m.y.’ or ‘m.yr’ could be used.

This convention has the advantage of distinguishing

‘dates’ from ‘intervals of time’ but it is not universally

applied.

19.1.1 Geological time units

It has commonly been the practice to distinguish

between geochronology, which is concerned with

geological time units and chronostratigraphy,

which refers to material stratigraphic units. The dif-

ference between these is that the former is an interval

of time that is expressed in years, whereas the latter is

a unit of rock: for example, the Chalk strata in north-

west Europe form a part of the Cretaceous System, a

unit of rock, and they were deposited in shallow seas

which existed in the area during a period of time that

we call the Cretaceous Period, an interval of time.

There is a hierarchical set of terms for geochronologi-

cal units that has an exact parallel in chronostrati-

graphic units (Fig. 19.1), but the distinction between

the two sets of terminologies is not made by all geol-

ogists and some (e.g. Zalasiewicz et al. 2004) question

whether it is either useful or necessary to employ this

dual stratigraphic terminology. The argument for

maintaining both is that it provides a distinction

between the physical reality of the strata themselves,

the rocks of, say, the Silurian System, and the more

abstract concept of the time interval during which

they were deposited, which would be the Silurian

Period. However, as Zalasiewicz et al. (2004) point

out, the use of ‘golden spikes’ (see below) for strati-

graphic correlation means that the beginning and end

of the period of time are now defined by a physical

point in a succession of strata, and thus there is no

real need to distinguish between the ‘time unit’ (geo-

chronology) and the ‘rock unit’ (chronostratigraphy)

as they amount to the same thing. The terms for the

geochronological units are described below, with the

equivalent chronostratigraphic units also noted

where they are also in common use.

Eons

These are the longest periods of time within the his-

tory of the Earth, which are now commonly divided

into three eons: the Archaean Eon up to 2.5 Ga, the

Proterozoic Eon from 2.5 Ga to 542 Ma (together

these constitute the Precambrian), and the Phanero-

zoic Eon from 542 Ma up to the present.

Eras

Eras are the three time divisions of the Phanerozoic:

the Palaeozoic Era up to 251 Ma, the Mesozoic Era

from then until 65.5 Ma and finally the Cenozoic Era

up to the present. Precambrian eras have also been

defined, for example dividing the Proterozoic into the

Palaeoproterozoic, the Mesoproterozoic and the Neo-

proterozoic.

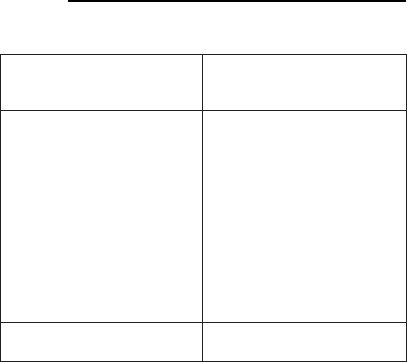

Geochronological units

(intervals of time

measured in years)

Eons

(e.g. Phanerozoic Eon)

Eras

(e.g. Cenozoic Era)

Periods

(e.g. Neogene Period)

Epochs

(e.g. Miocene Epoch)

Ages

Divisions into Early,

Middle and Late

Chronostratigraphic units

(material units defined by the

ages of the rocks within them)

Systems

(e.g. Neogene System)

Series

(e.g. Miocene Series)

Stages

(e.g. Messinian Stage)

Divisions into Lower,

Middle and Upper

Fig. 19.1 Nomenclature used for geochronological and

chronostratigraphic units.

298 Stratigraphy: Concepts and Lithostratigraphy

Periods/Systems

The basic unit of geological time is the period and

these are the most commonly used terms when refer-

ring to Earth history. The Mesozoic Era, for example,

is divided into three periods, the Triassic Period, the

Jurassic Period and the Cretaceous Period. The term

system is used for the rocks deposited in this time, e.g.

the Jurassic System.

Epochs/Series

Epochs are the major divisions of periods: some have

names, for example the Llandovery, Wenlock, Ludlow

and Pridoli in the Silurian, while others are simply

Early, (Mid-) and Late divisions of the period (e.g.

Early Cretaceous and Late Cretaceous). The chrono-

stratigraphic equivalent is the series, but it is impor-

tant to note that the terms Lower, Middle and Upper

are used instead of Early, Middle and Late. As an

example, rocks that belong to the Lower Triassic Ser-

ies were deposited in the Early Triassic Epoch. Logi-

cally a body of rock cannot be ‘Early’, nor can a period

of time be considered ‘Lower’ so it is important to

employ the correct adjective and use, for example,

‘Early Jurassic’ when referring to events which took

place during that time interval.

Ages/Stages

The smallest commonly used divisions of geological

time are ages, and the chronostratigraphic equivalent

is the stage. They are typically a few million years in

duration. For example, the Oligocene Epoch is divided

into the Rupelian and Chattian Ages (the Rupelian

and Chattian Stages of the Oligocene Series of rocks).

Chrons are short periods of time that are some-

times determined from palaeomagnetic information,

but these units do not have widespread usage outside

of magnetostratigraphy (21.4). The Quaternary can

be divided into short time units of only thousands to

tens of thousands of years using a range of techniques

available for dating the recent past, such as marine

isotope stages (21.5).

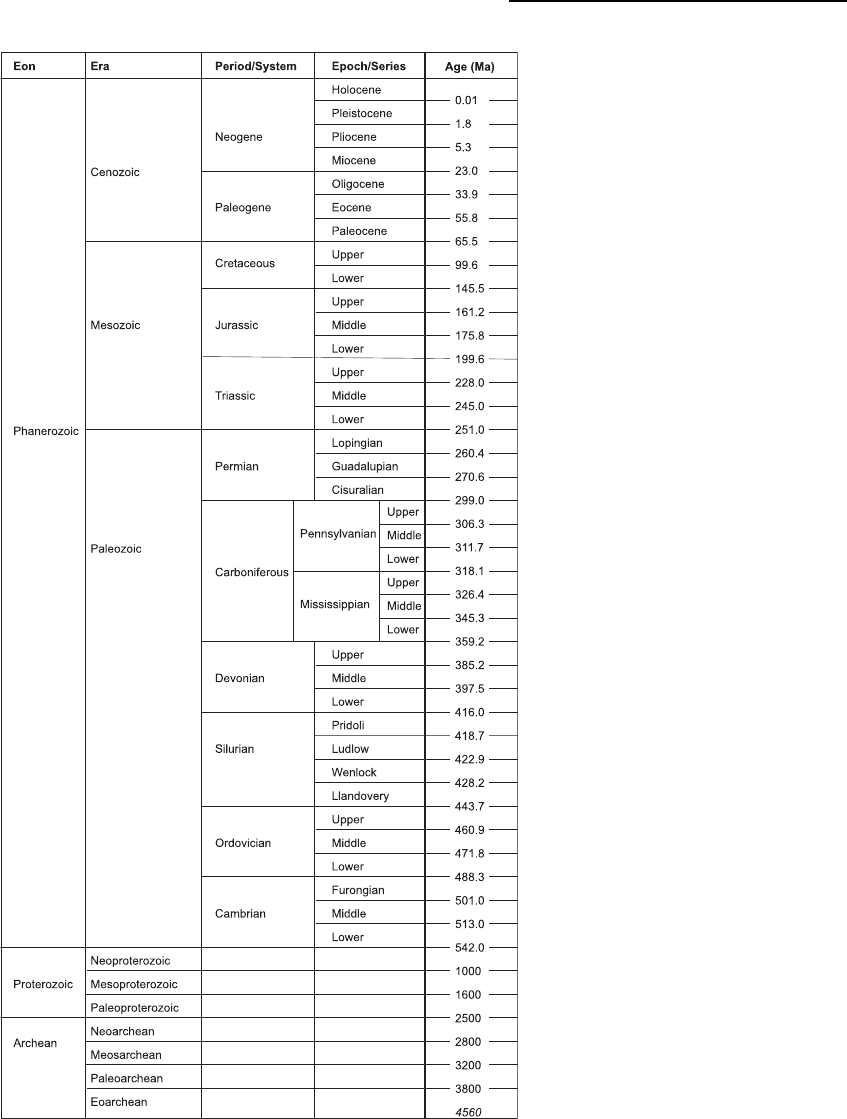

19.1.2 Stratigraphic charts

The division of rocks into stratigraphic units had been

carried out long before any method of determining the

geological time periods had been developed. The

main systems had been established and partly divided

into series and stages by the beginning of the 20th

century by using stratigraphic relations and biostrati-

graphic methods. Radiometric dating has provided a

time scale for the chronostratigraphic division of

rocks. The published geological time scales

(Fig. 19.2) have been constructed by integrating

information from biostratigraphy, magnetostratigra-

phy and data from radiometric dating to determine

the chronostratigraphy of rock units throughout the

Phanerozoic.

A simplified version of the most recent version of

the international stratigraphic chart published by

Gradstein et al. (2004) is shown in Fig. 19.2 (Grad-

stein & Ogg 2004). This shows the names of the

stratigraphic units that have been agreed by the Inter-

national Commission on Stratigraphy and the ages, in

millions of years, of the boundaries between each

unit. The ages shown are based on the best available

evidence and are not definitive. For reasons that will

be discussed in Chapter 21, it is often difficult to

directly measure the ages of a body of sedimentary

rocks in terms of millions of years. Strata are normally

defined stratigraphically as being, for example, ‘Oxfor-

dian’ on the basis of the fossils that they contain

(Chapter 20) or the physical relationships that they

have with other rock units (see Lithostratigraphy).

The time interval of the Oxfordian, 161.2 Ma to

155.0 Ma, that is shown on the chart is subject to

change as new information from radiometric dating

becomes available, or a recalibration is carried out.

Older versions of these stratigraphic charts show dif-

ferent ages for boundaries, and no doubt future charts

will also contain modifications to these dates. A unit

of sedimentary rocks is therefore never referred to as

being, say, 160 Ma old unless there has been a direct

radiometric measurement made of that unit: instead it

might be referred to as Oxfordian on the basis of its

fossils, and this will not change, whatever happens in

future versions of these charts.

19.1.3 Golden spikes

From the foregoing it should be clear that the Cambrian,

for example, is not defined as the interval of time

between 542 Ma and 488.3 Ma, but those numbers

are the ages that are currently thought to be the times

when the Cambrian Period started and ended. It is

Geological Time 299

Fig. 19.2 A stratigraphic chart with

the ages of the different divisions of

geological time. (Data from Gradstein

et al. 2004.)

300 Stratigraphy: Concepts and Lithostratigraphy

therefore necessary to have some other means of defin-

ing all of the divisions of the geological record, and the

internationally accepted approach is to use the ‘Global

Standard Section and Point’ (GSSP) scheme, other-

wise known as the process of establishing ‘golden

spikes’.

Some of the periods of the Phanerozoic were origin-

ally named after the areas where the rocks were first

described in the 18th and 19th centuries: the Cambrian

from Wales (the Roman name of which was Cambria),

the Devonian from Devon, England, the Permian after

an area in Russia and the Jurassic from the Jura moun-

tains of France. (Others were given names associated

with a region, such as the Ordovician and Silurian

Periods that have their origins in the names of ancient

Welsh tribes, and some have names related to the char-

acter of the rocks, such as the Carboniferous, coal-

bearing, and Cretaceous, from the Latin for chalk).

This effectively established the principle of a ‘type

area’, a region where the rocks of that age occur that

could act as a reference for other occurrences of similar

rocks. It was, in fact, mainly the fossil content that

provided the means of correlating: if strata from two

different places contain the same fossils, they are con-

sidered to be from the same period – this is the basis of

biostratigraphic correlation (20.6).

The GSSP scheme takes the ‘type area’ concept

further by defining the base of a period or epoch as

a particular point, in a particular succession of strata,

in a particular place. A ‘golden spike’ is metaphori-

cally hammered into the rocks at that point, and

all beds above it are defined as belonging to one

epoch/period and all below it to another (Walsh

et al. 2004). All other beds of similar age around the

world are then correlated with the strata that con-

tain the ‘golden spike’, using any of the correlation

techniques that are described in this and the following

chapters (lithostratigraphy, biostratigraphy, magne-

tostratigraphy, and so on). The locations chosen are

typically ones with fossiliferous strata, because the

fossils can be used for biostratigraphic correlation.

Successions where there appears to be continuous

sedimentation are also preferred so that all of the

time interval is represented by beds of material: if

there is a gap in the record at the GSSP location

due to a break in sedimentation there is the possi-

bility that there are rocks elsewhere which represent

a time interval that has no equivalent at the GSSP

site, and these beds could therefore not be defined

as being of one unit or the other. The exact choice

of horizon is usually made on the basis of fossil

content: the base of the Devonian, for example, is

defined by a golden spike in a succession of marine

strata in the Czech Republic at a point where a certain

graptolite is found in higher beds, but not in the

lower beds.

Golden Spikes have been established for about half

the Age/Stage boundaries in the Phanerozoic, with

the remainder awaiting the location of a suitable site

and international agreement. The procedure of defin-

ing GSSPs cannot easily be applied in older rocks

because it is essentially a biostratigraphic approach.

The scarcity of stratigraphically useful fossils in Pre-

cambrian strata means that only one pre-Phanerozoic

system has been defined so far: this is the Ediacaran

Period/System, the youngest part of the Neoprotero-

zoic Era. Other Precambrian boundaries have been

ascribed with ages, a Global Standard Stratigraphic

Age, or ‘GSSA’. Therefore, in contrast to the Phaner-

ozoic, the Precambrian is largely defined in terms of

the age of the rocks in millions of years: for example,

the Palaeoproterozoic is an era that is defined as being

between 2500 Ma and 1600 Ma.

19.2 STRATIGRAPHIC UNITS

The International Stratigraphic Chart and the Geologic

Time Scale that it shows provides an overall frame-

work within which we can place all the rocks on

Earth and the events that have taken place since the

planet formed. It is, however, of only limited relevance

when faced with the practical problems of determining

the stratigraphic relationships between rocks in the

field. Strata do not have labels on them which imme-

diately tell us that they were deposited in a particular

epoch or period, but they do contain information that

allows us to establish an order of formation of units

and for us to work out where they fit in the overall

scheme. There are a number of different approaches

that can be used, each based on different aspects of

the rocks, and each of which is of some value indivi-

dually, but are most profitably used in combinations.

First, a body of rock can be distinguished and

defined by its lithological characteristics and its strati-

graphic position relative to other bodies of rock: these

are lithostratigraphic units and they can readily

be defined in layered sedimentary rocks. Second, a

body of rock can be defined and characterised by its

fossil content, and this would be considered to be a

Stratigraphic Units 301

biostratigraphic unit (20.6). Third, where the age

of the rock can be directly or indirectly determined, a

chronostratigraphic unit can be defined (21.3.3):

chronostratigraphic units have upper and lower

boundaries that are each isochronous surfaces,

that is, a surface that formed at one time. The fourth

type of stratigraphic unit is a magnetostratigraphic

unit, a body of rock which exhibits magnetic proper-

ties that are different to adjacent bodies of rock in the

stratigraphic succession (21.4.3). Finally, bodies of

rock can be defined by their position relative to

unconformities or other correlatable surfaces: these

are sometimes called allostratigraphic units, but

this approach is now generally referred to as

‘Sequence Stratigraphy’, which is the subject of

Chapter 23. Each of these approaches to stratigraphy

are covered in this and the following chapters.

19.3 LITHOSTRATIGRAPHY

In lithostratigraphy rock units are considered in

terms of the lithological characteristics of the strata

and their relative stratigraphic positions. The relative

stratigraphic positions of rock units can be deter-

mined by considering geometric and physical rela-

tionships that indicate which beds are older and

which ones are younger. The units can be classified

into a hierarchical system of members, formations

and groups that provide a basis for categorising and

describing rocks in lithostratigraphic terms.

19.3.1 Stratigraphic relationships

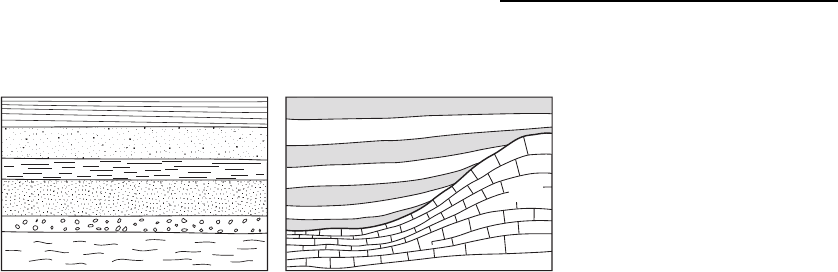

Superposition

Provided the rocks are the right way up (see below)

the beds higher in the stratigraphic sequence of depos-

its will be younger than the lower beds. This rule can

be simply applied to a layer-cake stratigraphy but

must be applied with care in circumstances where

there is a significant depositional topography (e.g.

fore-reef deposits may be lower than reef-crest rocks:

Fig. 19.3).

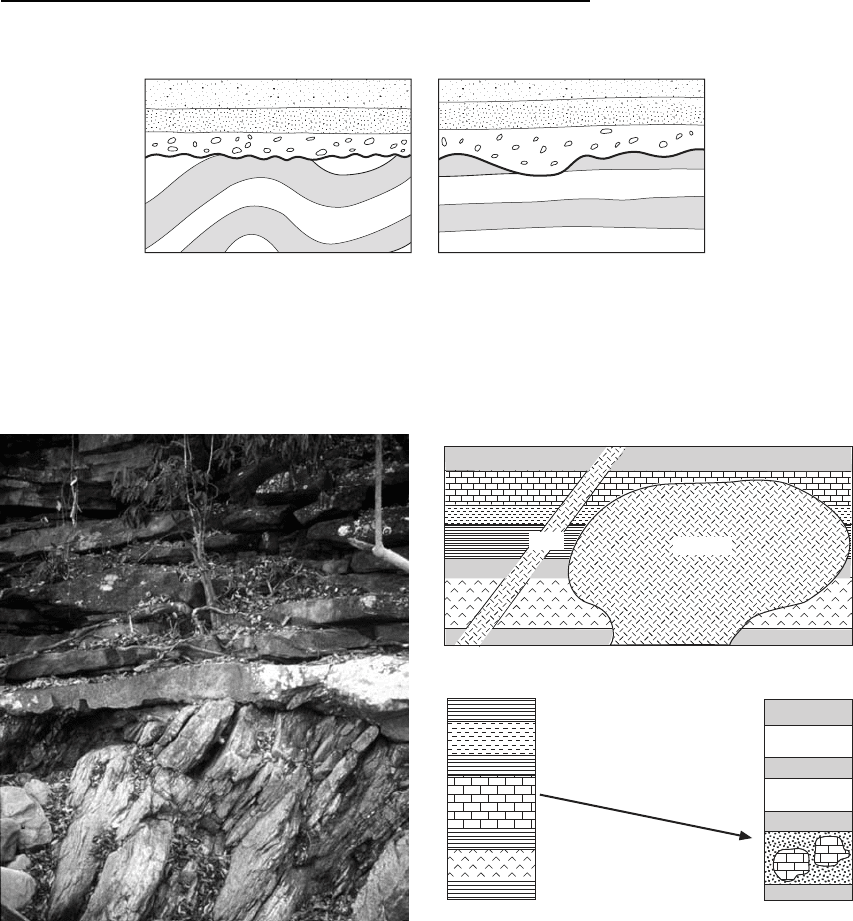

Unconformities

An unconformity is a break in sedimentation and

where there is erosion of the underlying strata this

provides a clear relationship in which the beds below

the unconformity are clearly older than those above it

(Figs 19.4 & 19.5). All rocks which lie above the

unconformity, or a surface that can be correlated

with it, must be younger than those below. In cases

where strata have been deformed and partly eroded

prior to deposition of the younger beds, an angular

unconformity is formed. A disconformity marks a

break in sedimentation and some erosion, but without

any deformation of the underlying strata.

Cross-cutting relationships

Any unit that has boundaries that cut across other

strata must be younger than the rocks it cuts. This is

most commonly seen with intrusive bodies such as

batholiths on a larger scale and dykes on a smaller

scale (Fig. 19.6). This relationship is also seen in

fissure fills, sedimentary dykes (18.1.3) that form by

younger sediments filling a crack or chasm in older

rocks.

Included fragments

The fragments in a clastic rock must be made up of a

rock that is older than the strata in which they are

Layer-cake stratigraphy

Stratigraphic relations around a

reef or similar structure

reef

Fig. 19.3 Principles of superposi-

tion: (a) a ‘layer-cake’ stratigra-

phy; (b) stratigraphic relations

around a reef or similar feature

with a depositional topography.

302 Stratigraphy: Concepts and Lithostratigraphy

found (Fig. 19.6). The same relationship holds true for

igneous rocks that contain pieces of the surrounding

country rock as xenoliths (literally ‘foreign rocks’).

This relationship can be useful in determining the age

relationship between rock units that are some dis-

tance apart. Pebbles of a characteristic lithology can

provide conclusive evidence that the source rock type

was being eroded by the time a later unit was being

deposited tens or hundreds of kilometres away.

Unconformities

Angular unconformity: deformation and

erosion prior to deposition of younger beds

Disconformity: break in deposition and

erosion within a stratigraphic succession

Fig. 19.4 Gaps in the record are represented by unconformities: (a) angular unconformities occur when older rocks have been

deformed and eroded prior to later deposition above the unconformity surface; (b) disconformities represent breaks in

sedimentation that may be associated with erosion but without deformation.

Fig. 19.5 An angular unconformity between horizontal

sandstone beds above and steeply dipping shaly beds below.

batholith

strata containing clasts eroded

from an older bed

dyke

Cross-cutting relationships

Included fragments

older beds

younger beds

Fig. 19.6 Stratigraphic relationships can be simple

indicators of the relative ages of rocks: (a) cross-cutting

relations show that the igneous features are younger than

the sedimentary strata around them; (b) a fragment of an

older rock in younger strata provides evidence of relative

ages, even if they are some distance apart.

Lithostratigraphy 303

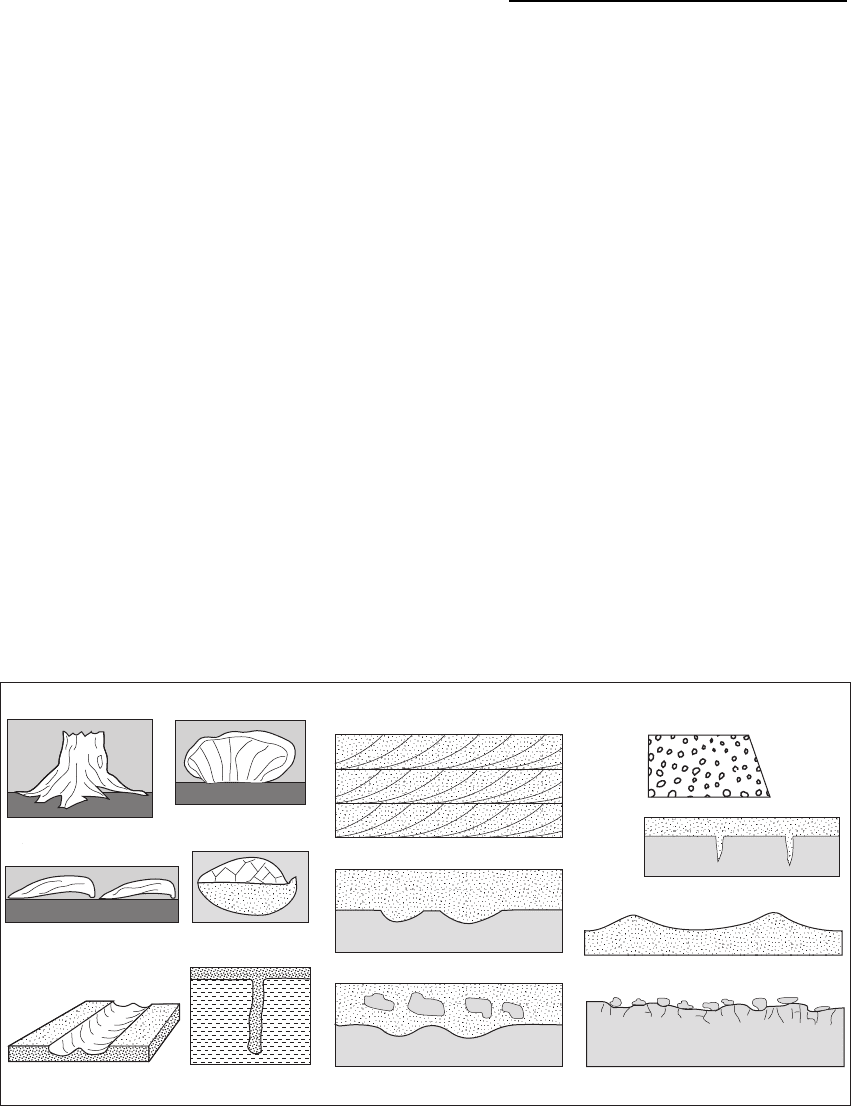

Way-up indicators in sedimentary rocks

The folding and faulting of strata during mountain

building can rotate whole successions of beds (formed

as horizontal or nearly horizontal layers) through any

angle, resulting in beds that may be vertical or com-

pletely overturned. In any analysis of deformed strata,

it is essential to know the direction of younging, that

is, the direction through the layers towards younger

rocks. The direction of younging can be determined

by small-scale features that indicate the way-up of the

beds (Fig. 19.7) or by using other stratigraphic tech-

niques to determine the order of formation.

19.3.2 Lithostratigraphic units

There is a hierarchical framework of terms used for

lithostratigraphic units, and from largest to smallest

these are: ‘Supergroup’, ‘Group’, ‘Formation’, ‘Mem-

ber’ and ‘Bed’. The basic unit of lithostratigraphic

division of rocks is the formation, which is a body

of material that can be identified by its lithological

characteristics and by its stratigraphic position. It

must be traceable laterally, that is, it must be mappable

at the surface or in the subsurface. A formation should

have some degree of lithological homogeneity and its

defining characteristics may include mineralogical

composition, texture, primary sedimentary structures

and fossil content in addition to the lithological compo-

sition. Note that the material does not necessarily have

to be lithified and that all the discussion of terminology

and stratigraphic relationships applies equally to

unconsolidated sediment.

A formation is not defined in terms of its age either

by isotopic dating or in terms of biostratigraphy.

Information about the fossil content of a mapping

unit is useful in the description of a formation but

the detailed taxonomy of the fossils that may define

the relative age in biostratigraphic terms does not

form part of the definition of a lithostratigraphic

unit. A formation may be, and often is, a diachro-

nous unit , that is, a deposit with the same lithological

properties that was formed at different times in differ-

ent places (19.4.2).

A formation may be divided into smaller units in

order to provide more detail of the distribution of

lithologies. The term member is used for rock units

that have limited lateral extent and are consistently

related to a particular formation (or, rarely, more

than one formation). An example would be a forma-

tion composed mainly of sandstone but which

included beds of conglomerate in some parts of the

area of outcrop. A number of members may be defined

Body fossils

Tree stump

Bioherm

(coral, stromatolite)

Stable orientation of

convex shells

Geopetal structures

Tracks and trails

Burrows

Trace fossils

Sedimentary structures

Cross-stratification

Scours

Included fragments

(rip-up clasts)

Weathered surface

Wave ripple crests

Mudcracks

Normally

graded

beds

Fig. 19.7 Way-up indicators in sedimentary rocks.

304 Stratigraphy: Concepts and Lithostratigraphy

within a formation (or none at all) and the formation

does not have to be completely subdivided in this way:

some parts of a formation may not have a member

status. Individual beds or sets of beds may be named if

they are very distinctive by virtue of their lithology or

fossil content. These beds may have economic signifi-

cance or be useful in correlation because of their

easily recognisable characteristics across an area.

Where two or more formations are found asso-

ciated with each other and share certain characteris-

tics they are considered to form a group. Groups are

commonly bound by unconformities which can be

traced basin-wide. Unconformities that can be identi-

fied as major divisions in the stratigraphy over the

area of a continent are sometimes considered to be the

bounding surfaces of associations of two or more

groups known as a supergroup.

19.3.3 Description of lithostratigraphic units

The formation is the fundamental lithostratigraphic

unit and it is usual to follow a certain procedure in

geological literature when describing a formation to

ensure that most of the following issues are consid-

ered. Members and groups are usually described in a

similar way.

Lithology and characteristics

The field characteristics of the rock, for example, an

oolitic grainstone, interbedded coarse siltstone and

claystone, a basaltic lithic tuff, and so on form the

first part of the description. Although a formation will

normally consist mainly of one lithology, combina-

tions of two or more lithologies will often constitute a

formation as interbedded or interfingering units. Sedi-

mentary structures (ripple cross-laminations, normal

grading, etc.), petrography (often determined from

thin-section analysis) and fossil content (both body

and trace fossils) should also be noted.

Definition of top and base

These are the criteria that are used to distinguish beds

of this unit from those of underlying and overlying

units; this is most commonly a change in lithology

from, say, calcareous mudstone to coral boundstone.

Where the boundary is not a sharp change from one

formation to another, but is gradational, an arbitrary

boundary must be placed within the transition. As an

example, if the lower formation consists of mainly

mudstone with thin sandstone beds, and the upper is

mainly sandstone with subordinate mudstone, the

boundary may be placed at the point where sandstone

first makes up more than 50% of beds. A common

convention is for only the base of a unit to be defined

at the type section: the top is taken as the defined

position of the base of the overlying unit. This con-

vention is used because at another location there may

be beds at the top of the lower unit that are not

present at the type locality: these can be simply

added to the top without a need for redefining the

formation boundaries.

Type section

A type section is the location where the lithological

characteristics are clear and, if possible, where the

lower and upper boundaries of the formation can be

seen. Sometimes it is necessary for a type section to be

composite within a type area, with different sections

described from different parts of the area. The type

section will normally be presented as a graphic sedi-

mentary log and this will form the stratotype. It must

be precisely located (grid reference and/or GPS loca-

tion) to make it possible for any other geologist to visit

the type section and see the boundaries and the litho-

logical characteristics described.

Thickness and extent

The thickness is measured in the type section, but

variations in the thickness seen at other localities

are also noted. The limits of the geographical area

over which the unit is recognised should also be

determined. There are no formal upper or lower limits

to thickness and extent of rock units defined as a

formation (or a member or group). The variability of

rock types within an area will be the main constraint

on the number and thickness of lithostratigraphic

units that can be described and defined. Quality and

quantity of exposure also play a role, as finer subdivi-

sion is possible in areas of good exposure.

Other information

Where the age for the formation can be determined

by fossil content, radiometric dating or relationships

with other rock units this may be included, but note

Lithostratigraphy 305

that this does not form part of the definition of the

formation. A formation would not be defined as, for

example, ‘rocks of Burdigalian age’, because an inter-

pretation of the fossil content or isotopic dating infor-

mation is required to determine the age. Information

about the facies and interpretation of the environ-

ment of deposition might be included but a formation

should not be defined in terms of depositional envi-

ronment, for example, ‘lagoonal deposits’, as this is an

interpretation of the lithological characteristics. It is

also useful to comment on the terminology and defi-

nitions used by previous workers and how they differ

from the usage proposed.

19.3.4 Lithostratigraphic nomenclature

It helps to avoid confusion if the definition and nam-

ing of stratigraphic units follows a set of rules. Formal

codes have been set out in publications such as the

‘North American Stratigraphic Code’ (North American

Commission on Stratigraphic Nomenclature 1983)

and the ‘International Stratigraphic Guide’ (Salvador

1994). A useful summary of stratigraphic methods,

which is rather more user-friendly than the formal

documents, is a handbook called ‘Stratigraphical Pro-

cedure’ (Rawson et al. 2002).

The name of the formation, group or member must

be taken from a distinct and permanent geographical

feature as close as possible to the type section. The

lithology is often added to give a complete name such

as the Kingston Limestone Formation, but it is not

essential, or necessarily desirable if the lithological

characteristics are varied. The choice of geographical

name should be a feature or place marked on topo-

graphic maps such as a river, hill, town or village. The

rules for naming members, groups and supergroups

are essentially the same as for formations, but note

that it is not permissible to use a name that is already

in use or to use the same name for two different ranks

of lithostratigraphic unit. There are some exceptions

to these rules of nomenclature that result from histor-

ical precedents, and it is less confusing to leave a well-

established name as it is rather than to dogmatically

revise it. Revisions to stratigraphic nomenclature may

become necessary when more detailed work is carried

out or more information becomes available. New

work in an area may allow a formation to be subdi-

vided and the formation may then be elevated to the

rank of group and members may become formations

in their own right. For the sake of consistency the

geographical name is retained when the rank of the

unit is changed.

19.3.5 Lithodemic units: non-stratiform

rock units

The concepts of division into stratigraphic units were

developed for rock bodies that are stratiform, layered

units, but many metamorphic, igneous plutonic and

structurally deformed rocks are not stratiform and

they do not follow the rules of superposition. Non-

stratiform bodies of rock are called lithodemic units.

The basic unit is the lithodeme and this is equivalent

in rank to a formation and is also defined on litholo-

gical criteria. The word ‘lithodeme’ is itself rarely used

in the name: the body of rock is normally referred to

by its geographical name and lithology, such as the

White River Granite or Black Hill Schist. An associa-

tion of lithodemes that share lithological properties,

such as a similar metamorphic grade, is referred to

as a suite: the term complex is also used as the

equivalent to a group for volcanic or tectonically

deformed rocks.

19.4 APPLICATIONS OF

LITHOSTRATIGRAPHY

19.4.1 Lithostratigraphy and geological maps

Part of the definition of a formation is that it should be

a ‘mappable unit’, and in practice this usually means

that the unit can be represented on a map of a scale of

1:50,000, or 1:100,000. Maps at this scale therefore

show the distribution of formations and may also

show where members and named beds occur. The

stratigraphic order and, where appropriate, lateral

relationships between the different lithostratigraphic

units are normally shown in a stratigraphic key at the

side of the map. In regions of metamorphic, intrusive

igneous and highly deformed rocks the mapped units

are lithodemes. There are no established rules for the

colours used for different lithostratigraphic and litho-

demic units on these maps, but each national geolo-

gical survey usually has its own scheme. Geological

maps that cover larger areas, such as a whole country

or a continent, are different: they usually show the

306 Stratigraphy: Concepts and Lithostratigraphy

distribution of rocks in terms of chronostratigraphic

units, that is, on the basis of their age, not lithology.

19.4.2 Lithostratigraphy and environments

It is clear from the earlier chapters on the processes

and products of sedimentation that the environment

of deposition has a fundamental control on the litho-

logical characteristics of a rock unit. A formation,

defined by its lithological characteristics, is therefore

likely to be composed of strata deposited in a particu-

lar sedimentary environment. This has two important

consequences for any correlation of formations in any

chronostratigraphic (time) framework.

First, in any modern environment it is obvious that

fluvial sedimentation can be occurring on land at the

same time as deposition is happening on a beach, on a

shelf and in deeper water. In each environment the

characteristics of the sediments will be different and

hence they would be considered to be different forma-

tions if they are preserved as sedimentary rocks. It

inevitably follows that formations have a limited lat-

eral extent, determined by the area of the depositional

environment in which they formed and that two or

more different formations can be deposited at the

same time.

Second, depositional environments do not remain

fixed in position through time. Consider a coastline

(Fig. 19.8), where a sandy beach (foreshore) lies

between a vegetated coastal plain and a shoreface

succession of mudstones coarsening up to sandstones.

The foreshore is a spatially restricted depositional

environment: it may extend for long distances along

a coast, but seawards it passes into the shallow mar-

ine, shoreface environment and landwards into con-

tinental conditions. The width of deposit produced in

a beach and foreshore environment may therefore be

only a few tens or hundreds of metres. However, a

foreshore deposit will end up covering a much larger

area if there is a gradual rise or fall of sea level relative

to the land. If sea level slowly rises the shoreline will

move landwards and through time the place where

sands are being deposited on a beach would have

moved several hundreds of metres (Fig. 19.8). These

depositional environments (the coastal plain, the

sandy foreshore and the shoreface) will each have

distinct lithological characteristics that would allow

them to be distinguished as mappable formations. The

foreshore deposits could therefore constitute a forma-

tion, but it is also clear that the beach deposits were

formed earlier in one place (at the seaward extent)

than another (at the landward extent). The same

would be true of formations representing the deposits

of the coastal plain and shoreface environments:

through time the positions of the depositional envi-

ronments migrate in space. From this example, it is

evident that the body of rock that constitutes a for-

mation would be diachronous and both the upper and

lower boundaries of the formation are diachronous

surfaces.

There is also a relationship between environments

of deposition and the hierarchy of lithostratigraphic

units. In the case of a desert environment there may

be three main types of deposits (Fig. 8.12): aeolian

sands, alluvial fan gravels and muddy evaporites

deposited in an ephemeral lake. Each type of deposit

would have distinctive lithological characteristics

that would allow them to be distinguished as three

separate formations, but the association of the three

could usefully be placed into a group. A distinct

change in environment, caused, perhaps, by sea-

level rise and marine flooding of the desert area,

would lead to a different association of deposits,

which in lithostratigraphic terms would form a sepa-

rate group. Subdivision of the formations formed in

this desert environment may be possible if scree

deposits around the edge of the basin occur as

small patches amongst the other facies. When lithi-

fied the scree would form a sedimentary breccia,

recognisable as a separate member within the other

formations, but not sufficiently widespread to be con-

sidered a separate formation.

19.4.3 Lithostratigraphy and correlation

Correlation in stratigraphy is usually concerned with

considering rocks in a temporal framework, that is,

we want to know the time relationships between differ-

ent rock units – which ones are older, which are

younger and which are the same age. Correlation on

the basis of lithostratigraphy alone is difficult because,

as discussed in the previous section, lithostratigraphic

units are likely to be diachronous. In the example of

the lithofacies deposited in a beach environment

during a period of rising sea level (Fig. 19.8) the

lithofacies has different ages in different places. There-

fore the upper and lower boundaries of this lithofacies

will cross time-lines (imaginary lines drawn across

Applications of Lithostratigraphy 307