Fouracre P. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500-c. 700

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Christianity amongst the Britons, Dalriadan Irish and Picts 433

0

0

50

50

150 miles

100 200 km150

100

Key

Eccles

Eccles-

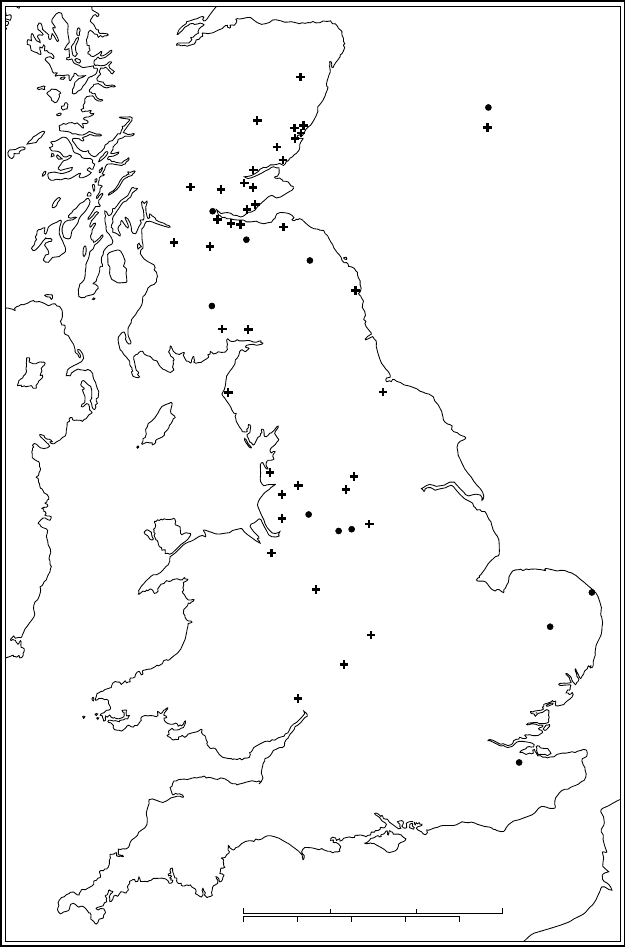

Map 13 Distribution of Eccles place-names

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

434 clare stancliffe

its author records the transmission of information as well as his own visit to

Britain.

24

Whether or not we can give any credence to the Life’s postulated link

between monasticism in South Wales and the visits to Britain of Germanus

of Auxerre (429 and perhaps c.440), the education of Samson in a monastery

under Illtud from a very early age probably points to the founding of Illtud’s

monastery at some point in the fifth century, presumably at Llantwit (i.e. Llan

Ilduti).

25

Continuity of Roman Christianity and its spread further west and north is

also indicated by Patrick’s writings. We have already seen that these imply the

existence of a Christian community near the Irish Sea, while Patrick himself is

prime evidence for the spread of Christianity west to Ireland. His letter directed

against the British chieftain Coroticus associates Christianity and Roman

society – something we find again in the following century with Gildas;

26

further, it implies Christianity’s spread to parts of Britain north of the former

Roman frontier marked by Hadrian’s Wall. Although one cannot be certain,

the likelihood is that this Coroticus was the ruler of Strathclyde, a British king-

dom centred at Dumbarton (on the Clyde);

27

and Patrick’s letter indicates that

Coroticus and his men were nominal Christians.

28

This literary indication of

the spread of Christianity into what is now Scotland can be confirmed: the

Latinus stone at Whithorn with its newly recognised Constantinian form of

the chi-rho testifies to Christianity there in the fifth century, while the scat-

ter of other stones together with Eccles place-names indicates the spread of

Christianity up to the Clyde–Forth line by c.600.

29

Although the evidence for

Christianity is not extensive, that for paganism in those centuries is almost

non-existent, with the exception of Yeavering in north Northumberland; and

here, the paganism may well be that of the Anglo-Saxon invaders, not the

Britons.

30

Thus what appears to have happened is that the former Roman

frontier became irrelevant, and Christianity spread to all the British kingdoms,

perhaps even making some progress among the Picts further north.

Some of the complexity that may lurk behind these generalised inferences

can be illustrated by the case of Whithorn, which has been partially excavated

in recent years. Bede says that Whithorn was the episcopal seat for the British

bishop Ninian, who, unusually for the Britons, built a stone church there; in

24

Vita Samsonis,Preface 2; and cf. i.52; i.7, 41, 48. There is no evidence that its author knew Bede’s

works and that it should therefore be dated to the eighth century, as proposed by Flobert, pp. 108–11;

cf. Duine (1912–13 and 1914–15); Hughes (1981), p. 4;Wood (1988), pp. 380–4.

25

Vita Samsonis i.7 and 42;cf. Knight (1984), pp. 328–9.

26

Patrick, Epistola ii;cf. below, notes 40 and 43.

27

Binchy (1962), pp. 106–9;Dumville et al.(1993), pp. 107–15, esp. 114.

28

Patrick, Epistola 5,cf.Epistola 2.

29

Craig (1997); Thomas (1991–92); Barrow (1983); cf. Thomas (1968); Alcock (1992).

30

Cf. Hope-Taylor (1977), esp. pp. 158–61, 244–67, 277–8, 287–9, and Scull (1991).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Christianity amongst the Britons, Dalriadan Irish and Picts 435

Bede’s day, at least, it was dedicated to St Martin of Tours.

31

The site of the

church probably lay on the hilltop where the Latinus inscription was found and

the later medieval church built. The recent excavation, however, focussed lower

down on the southern slope of the hill, an area that initially lay outside the

inner religious precinct. The dig uncovered a complex development beginning

with an agricultural phase, then witnessing the import of lime, presumably

to make plaster or cement for significant building(s) nearby (on the hilltop?).

Next in the area excavated came a number of wattle or stake-walled buildings

and evidence of metalworking, together with sherds of amphorae imported

from the east Mediterranean between the late fifth and mid-sixth centuries,

and also fragments of glass vessels. The amphorae probably contained wine and

olive oil, while fine tablewares were also imported from North Africa. Mean-

while at Whithorn the boundary between the inner and the outer enclosures

shifted, so that most of the area excavated came to form part of the inner enclo-

sure, and burials began to take place there. The Mediterranean trade ended

around the mid-sixth century; but international trade with the continent soon

resumed, and flourished throughout the seventh century: imports included

some fifty-five glass cone beakers.

32

In some respects the written and archaeo-

logical evidence coheres. Clearly, Whithorn was an unusual, high-status site.

It had far-flung contacts with the Mediterranean, and then Francia; and the

ecclesiastical nature of at least part of the site is borne out by the discovery

of some cross-inscribed stones from the excavated area, and also fits with the

cemetery established there. But questions remain. For instance, were all the

glass vessels imported so that the bishop could feast in style,

33

or could some

have been intended for a secular lord based in the immediate vicinity, whose

rubbish might have spread over our site?

34

In all events, the implication is that

Whithorn belonged to a reasonably civilised world which was ‘post-Roman’

rather than ‘barbarian’: a remarkable fact when we recall that in 400 it was

outside the frontiers of the Roman Empire.

gildas’ witness and the outlines of the british church

Our knowledge of Britain in the sixth century depends to a considerable extent

upon the writings of a single author, Gildas. His major work, De Excidio

Britonum (often referred to as De Excidio Britanniae,‘The Ruin of Britain’),

is a superbly rhetorical denunciation of the failings of those in power, both

secular potentates and bishops. Through copious citations from the Bible,

Gildas seeks to open their eyes to the yawning gulf between their lip-service to

31

Bede, HE iii.4.

32

Hill (1997), esp. chs. 3 and 10.

33

Cf. Gildas’ evidence: below, note 44.

34

Cf. Thomas (1992), pp. 10–13;Hill (1997), pp. 299, 320.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

436 clare stancliffe

the Christian God, and what that same God requires in practice. There is an

urgency to Gildas’ appeal: he has imbibed the Old Testament view of a God

who would purge a sinful people through visitation of plague or conquest at the

hands of foreigners – witness the original Anglo-Saxon conquests.

35

At the time

that he was writing, probably the early 530s,

36

Britain was divided into a mosaic

of kingdoms or social groupings, British and Germanic, with the latter pre-

dominating to the south and east of a line drawn diagonally from Flamborough

Head to the Solent. Although peace between the Britons and Anglo-Saxons

had prevailed since Gildas’ birth some forty-four years previously,

37

his fel-

low countrymen’s behaviour was such as to provoke new disasters, unless they

repented.

When due allowance is made for Gildas’ slant and rhetoric, much can

be learned. First, Gildas had a concept of Britain as a single entity, though

subdivided into several kingdoms, and the sweep of the area he addressed

ran from Dumnonia in the south-west through Dyfed to Gwynedd in North

Wales.

38

Secondly, continuity from Roman Britain is frequently implied by

the flow of his historical chapters, which present a seamless account of British

Christianity from the days of the martyrs to the present;

39

by his use of the term

cives,‘citizens’, for the British, and designation of Latin as ‘our language’;

40

and by the very nature of his Latin prose style, which betrays his training in

the art of rhetoric, the hallmark of a late Roman education.

41

Throughout his

work, the assumption is that the British are all at least nominally Christian:

the bishops are castigated for their failure to denounce sin and preach God’s

word, but not for condoning paganism.

42

Contrariwise, the Saxons are ‘hateful

to God and man’.

43

Gildas’ work allows one to see a wealthy, established church, with its church

buildings and ecclesiastical hierarchy. Power and responsibility fell to the

bishops; and so greatly was ecclesiastical status coveted, that men bought the

office of both bishop and priest from local kings, or, failing that, travelled over-

seas to gain it.

44

Clerical marriage was recognised, though continuing sexual

relations after ordination as priest were not necessarily allowed.

45

Monasti-

cism was in existence, and its practitioners were then few in number, but

highly regarded by the author.

46

In this latter respect, the De Excidio differs

35

For example, Gildas, De Excidio i.13; xxii–xxiv.

36

Cf. Dumville (1984b); Stancliffe (1997), pp. 177–81.

37

Gildas, De Excidio xxvi.1.

38

Gildas, De Excidio xxviii; xxxi; xxxiii.1;cf. Dumville (1984a).

39

Gildas, De Excidio iv–xxvi.

40

For example Gildas, De Excidio xxvi.1; xxiii.3.

41

Lapidge (1984); Orlandi (1984); Wright (1984); Kerlou

´

egan (1987), pp. 559–64.

42

Gildas, De Excidio lxxvi; lxxxiii.1–2; lxxxv.2.But cf. note 11 above.

43

Gildas, De Excidio xxiii.1;cf.xcii.3.

44

Gildas, De Excidio lxvi–lxvii.W.H.Davies (1968), pp. 140–1.

45

Hughes (1966), pp. 41–3.

46

Herren (1990), pp. 71–6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Christianity amongst the Britons, Dalriadan Irish and Picts 437

from a later work of Gildas, only fragmentarily preserved: a letter replying

to a request for advice on various problems, particularly those arising from

a clash between relatively comfortable monasteries and individuals seeking a

more austere lifestyle.

47

What is interesting is that monasticism seems to have

expanded and diversified between the De Excidio and the Fragments.

48

We will

return to this question below; but here, we should note the implication that

Gildas’ life spanned a crucial period: the De Excidio belongs to late antiq-

uity as much as the early Middle Ages, whereas the Fragments belong to the

phase of monastic expansion and link us with the world of the great Irish

ascetic, Columbanus.

49

It has been plausibly argued that what we see here is

cause and effect: Gildas’ impassioned preaching in the De Excidio had per-

ceptible results, inspiring many to embrace the monastic life.

50

De Excidio’s

impact would have been considerably strengthened if the climatic disturbance

around 536 and plague of the 540s followed hard upon its publication, as seems

likely.

51

Other sources corroborate or add to Gildas’ evidence. We have what appear

to be penalties agreed for various offences at two British synods of approxi-

mately sixth-century date. One is headed ‘The Synod of North Britain’, and

provides us with welcome information on an area not covered by Gildas.

It has references to the status of bishop, priest, deacon, doctor (ecclesiastical

scholar), abbot and monk.

52

Nevertheless, our knowledge of the organisational

framework of the British church is incomplete because the surviving evidence

is patchy. A good case has been made for each cantref of Dyfed having its

own bishop, thus suggesting small-scale, territorial dioceses.

53

Dyfed, with its

extensive colonisation from Ireland, was not necessarily typical of all areas;

but nor was it necessarily untypical. Further to the east the evidence of the

Llandaff charters, which survive only in edited form in the twelfth-century

Book of Llandaff, has been taken to imply a bishopric in Ergyng (south-west

Herefordshire) in the sixth century, which would have been comparable in

size to the Dyfed dioceses. Later, however, it may have expanded west to cover

Gwent also.

54

Evidence pointing in a different direction occurs in the Life of

St Samson,ifwemay trust it. Here, Bishop Dubricius of (we may assume)

Ergyng is found ordaining Samson at Llantwit monastery, in modern South

47

Gildas, Fragmenta;Sharpe (1984a).

48

Herren (1990).

49

Cf. Davies (1968), p. 141; Columbanus, Epistulae i.6.

50

Sharpe (1984a), p. 199.

51

Cf. (with caution) Keys (1999), pp. 109–18.

52

Sinodus Aquilonalis Britaniae 1–3.Fordoctor, see Scheibelreiter, chapter 25 below.

53

Charles-Edwards (1970–72).

54

Hughes (1981), esp. pp. 7–8.Cf. Wendy Davies (1978), ch. 8, esp. pp. 144–5, 149–50, 152–9, who

thinks the trend was the other way round: that a larger sixth-century diocese later became restricted

to Ergyng. Knight (1984), p. 341.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

438 clare stancliffe

Glamorgan, and even appointing him to monastic office in Piro’s monastery

on Caldey Island, Dyfed. This cannot have lain within a territorial diocese

based on Ergyng; but since Dubricius spent every Lent there, we may be seeing

a special relationship between Caldey and Ergyng.

55

A further point is that

when Samson was consecrated bishop, there is no indication that this was to

any specific see.

56

Perhaps, then, there were some monasteries supervised by a

bishop of a more distant diocese than that in which they lay geographically;

and some monastic bishops, as well as bishops of territorial dioceses. The latter

appear to have retained control over monasteries, unlike their Irish equivalents;

but we should not overemphasise the contrast.

57

As regards the question of where real power and influence lay, we should

ponder the implications of Bede’s story of the British church’s dealings with

Augustine. According to Bede, Augustine summoned the bishops and ecclesias-

tical scholars (doctores)ofthe British to meet him, and after fruitless discussions

demonstrated that Roman ways were right through working a miracle. The

British delegation was apparently convinced by this, but asked for a second

synod with wider representation. Seven British bishops and many most learned

men (doctissimi), principally from the monastery of Bangor, came to this; and

before coming, they sought advice from a holy anchorite. When they had to

make a decision, it was the anchorite’s advice that they followed.

58

There are

two significant points here: first, doctores, particularly monastic doctores,were

involved at both synods alongside bishops. Doctores figure in the rulings of

the ‘Synod of North Britain’ as those responsible for assigning penances, even

to bishops.

59

Their presence alongside bishops in the synods meeting with

Augustine can be paralleled by the presence of similar ecclesiastical scholars,

who could equal bishops in status, at seventh-century Irish synods.

60

Thus

matters of the greatest significance in the British church would appear to have

been the concern not simply of the bishops, but of ecclesiastical scholars also.

Secondly, the fact that the anchorite’s advice was sought and followed implies

that his spiritual wisdom and moral authority were accorded recognition at

the highest level. Whether this was a recent result of the ascetic movement we

cannot know, though it seems likely. Thus while British bishops continued to

be the leaders of the British church, they were not the sole source of author-

ity in the early seventh century, nor is there any mention at this date of an

‘overbishop’ or metropolitan. Instead, synods were clearly important, and these

allowed for the participation of doctores alongside bishops in decision-making.

55

Vita Samsonis i.13, 15, 33–6;cf. Hughes (1981), p. 15.

56

Vita Samsonis i.43–5.

57

See Charles-Edwards (1970–72), esp. p. 260;Sharpe (1984b);

´

OCr

´

oin

´

ın (1995), p. 162;Mac

Shamhr

´

ain (1996), ch. 6, esp. pp. 168–72, 206;cf. Hughes (1981).

58

Bede, HE ii.2;cf. Stancliffe (1999), pp. 124–33.

59

Sinodus Aquilonalis Britaniae 1.

60

Charles-Edwards (2000), pp. 276–7;Kelly (1988), p. 41.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Christianity amongst the Britons, Dalriadan Irish and Picts 439

monasticism

It is highly likely that monasticism reached Britain from Gaul at the end of

the fourth or during the fifth century. Gaul was home to two major monastic

movements. One derived from the monk-bishop, Martin of Tours (d. 397)

via his disciples, and via the hagiographical writings about him of Sulpicius

Severus. The other movement derived from twin foci in Provence: the island

monastery of L

´

erins, and the writings of John Cassian, a monk from the east

who had visited the Desert Fathers in Egypt, and wrote about them in the

early fifth century after settling in Marseilles. Both currents probably affected

Britain during the fifth century.

Monasticism in early Britain is a complex subject, partly because there

has been much speculation about its origins and achievements, and about its

relationship to bishops and territorial dioceses; but equally because there is

confusion as to what is meant by ‘monasticism’ and ‘monasteries’. On the one

hand, there is a problem as to whether we can always differentiate between

monasteries and communities of clerics. In the sixth century at least there

probably were some monasteries, as we think of them, consisting of men living

in a community in accordance with monastic vows and under the direction

of an abbot, with only a minority of them in the orders of deacon or priest.

61

At the same time, given that clergy might legitimately be married and so

presumably had their own independent households, and given the distinction

implicit in Gildas’ De Excidio between the responsibilities of clerics as opposed

to the withdrawn monks (which implies that the latter bore no responsibility

for pastoral care), we may infer that pastoral care was not the concern of

monasteries, but rather of separate, secular clergy.

62

However, there may also

have been households of clerics living together, as on the continent; and in the

course of time the distinction between such clerical communities and monastic

communities appears to have become increasingly blurred.

63

A further confusion arises from the overlap between ‘monasticism’ and

‘asceticism’, as illustrated in the Life of Samson.Samson was placed in Illtud’s

monastery (Llantwit) as a young child. When he grew up he desired a stricter,

more religious life than Illtud’s rather lax establishment afforded, and was able

to transfer to the monastery of one Piro, on Caldey Island, which afforded

him more scope for extended prayer. When chosen to succeed Piro as abbot –

the latter having fallen down a well while inebriated – Samson governed the

61

Praefatio Gildae 1–2; Vita Samsonis i.13–15, and passim.

62

Hughes (1966), pp. 41–3;Gildas, De Excidio lxv;Herren (1990), pp. 74–5;Victory (1977), p. 51. The

different inferences drawn by Pryce (1992), pp. 51–2, seem less securely founded on the sixth-century

evidence.

63

Davies (1982), pp. 149–50.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

440 clare stancliffe

monks in accordance with a Rule, and was personally so abstemious that he was

regarded as more of a ‘hermit’ than a ‘cenobite’.

64

After visiting Ireland Samson

did not resume his duties as abbot on Caldey, but took three companions and

established an eremitic settlement in a fort in a ‘desert’ near the River Severn.

He did not stay with the others, however, but spent most of his time in solitary

prayer in a cave, returning to the fort only for mass on Sundays. Summoned

from his retreat by a synod and unwillingly put in charge of another monastery,

he was soon after consecrated bishop; but then announced that he had been

called to live as a peregrinus,astranger or ‘pilgrim’.

65

In Celtic countries this

developed a specialised sense: renunciation of one’s homeland for the sake

of Christ, never to return. Samson therefore set out, visiting some of his own

family’s monasteries in South Wales en route for Cornwall. There he preached to

pagans and founded a monastery, finally crossing to Brittany where he founded

further monasteries, and ended his days.

66

Clearly what we see here is a single

monastic vocation which found expression in a variety of forms, as a monk,

a hermit and a peregrinus, while the family monasteries he visited might have

been closer to household asceticism rather than full-blown monasticism; there

are plenty of indications that the headship of such monasteries was normally

handed down within a kindred. In these circumstances, to attempt a rigid

distinction between asceticism and monasticism would be inappropriate.

67

Samson’s desire to exchange a lax community for a more religious one and

to devote himself to solitary prayer tallies with the sixth-century evidence

of Gildas’ Fragments. These reveal great diversity of monastic practice. Some

established monasteries enjoyed a good diet, including meat and beer, as well

as eggs, cheese, milk, vegetables and bread; at others, the food was much

less plentiful, while the extreme ascetics used bread and water as their staple.

Illtud’s monks appear to have supported themselves by farming, and certainly at

Bangor-is-Coedall monks undertook manual labour; but in some communities

this apparently fell to designated worker monks, rather than being undertaken

by all, while at the ascetic extreme, the use of animals even to draw ploughs

was rejected, the monks doing all work by hand.

68

This was the period that later generations regarded as that of the founder-

saints of the Welsh church. Reliable evidence is unfortunately lacking on

these, though a reading of an inscription at Llandewi-brefi preserved by an

antiquarian – the crucial word is now missing – may at least provide

64

Vita Samsonis i.6–10, 20–1, 36.

65

Vita Samsonis i.40–5.

66

See below, pp. 443–4 and also Davies, chapter 9 above; Olson (1989), pp. 9–20.

67

Vita Samsonis i.14, 16, 29–31, 40, 45, 52.Hughes (1966), pp. 76–7.Cf.Markus (1990), pp. 66–8;

Stancliffe (1983), pp. 30–8; Knight (1984), pp. 328–9.

68

Praefatio Gildae 1, 2, 22, 26, and cf. 7–10; Vita Samsonis i.12, and cf. i.35;Gildas, Fragmenta 2–4;

Bede, HE ii.2.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Christianity amongst the Britons, Dalriadan Irish and Picts 441

seventh-century testimony to St David, patron saint of Wales. His death is

recorded in the Welsh annals at 601, and in various Irish annals some twelve

years earlier, which suggests a mid to late sixth-century floruit. This is plausible,

but unverifiable.

69

The account of his community’s extremely ascetic lifestyle

given in Rhigyfarch’s eleventh-century Life does not look like a fabrication of

the 1090s, and has interesting parallels in Gildas’ Fragments; but we do not

know what sources lie behind it.

70

Even disregarding such late evidence, how-

ever, the sixth century still appears as a time of ascetic fervour on the part

of some, which led to new monastic foundations (like those of Samson), and

which probably resulted in growing numbers of monks. This is implied by

Gildas’ Fragments, and attested by Bede’s account of the monastery of Bangor-

is-Coed in the early seventh century, which he records as containing over 2000

monks.

71

This must have been a remarkable community – at least until the

Northumbrian slaughter of 1200 of its inmates in 616.

britons abroad

In thefifth and sixth centuries the Britonsremainedwithin aRoman penumbra,

with trading contacts to parts of the former Roman Empire.

72

These were

matched by cultural and ecclesiastical links. Gildas still regarded Latin as ‘our’

language, and some of his fellow countrymen journeyed abroad to receive

episcopal consecration, while churchmen with British names turn up as bishop

of Senlis in the mid-sixth century (Gonotiernus), or as an abbot in Burgundy in

591 (Carantocus). Thus Britons appear to have preceded as well as accompanied

the Irish peregrinus, Columbanus, on his continental travels.

73

Most remarkable

of all is a record of British churches with a bishop of their own in far-off Galicia

in the 560s and 570s.

74

The most densely colonised area was the western and northern part of

the Armorican peninsula, which by the late sixth century had been renamed

Brittania,Brittany. Officially, this remained part of an ecclesiastical province

mirroring the Roman Lugdunensis III, with its metropolis at Tours; and a series

of episcopal provincial meetings at Angers (453), Tours (461) and Vannes (462–

8)reveal the pre-Breton ecclesiastical structure, with bishops in the civitates

69

Gruffydd and Owen (1956–58); cf. Nash-Williams (1950), p. 98,no.116.See also Davies (1978),

p. 132. Annales Cambriae s.a. 601;cf. Miller (1977–78), pp. 44–8;Hughes (1980), pp. 67–100, esp.

90–1.

70

Rhigyfarch, Vita Davidis cc.21–30.

71

Bede, HE ii.2;Stancliffe (1999), pp. 124–9;cf.Herren (1990), p. 77.

72

Campbell (1996).

73

Gildas, De Excidio xxiii.3; lxvii.5–6. Councils of Orl

´

eans v and Paris iii, Concilia Galliae, ed. Munier

and de Clercq in CCSL 148,pp.160, 210.Jonas, Vita Columbani i.7; 13, 15 and 17;Dumville (1984c),

pp. 20–1.

74

Thompson (1968).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

442 clare stancliffe

of Rennes, Nantes and Vannes; and probably also amongst the Coriosolites

(perhaps based in the coastal stronghold of Alet), and amongst the Osismii in

the west, though here the location of the see is unknown.

75

The first probable

evidence of British churchmen in Armorica is the signature of one Mansuetus,

‘bishop of the Britons’, at the synod of Tours in 461 – though it is just possible

that he was a visiting bishop.

76

Certain proof of British churchmen actively

ministering to the (British) population comes from a letter written by the

bishops of Tours, Rennes and Angers between 509 and 521 to two priests with

the Brittonic names of Lovocat and Catihern. The priests had been travelling

around with portable altars, celebrating mass in private houses. What angered

the bishops was that they were accompanied by women known as conhospi-

tae, who administered the chalice.

77

These details are extremely interesting:

first, as regards the prominent role played by women, which parallels that of

deaconesses in the eastern church, but is scarcely attested in the west. Perhaps

the prohibition against ordaining deaconesses at the synods of Epaone (517)

and Orl

´

eans ii (533) should be seen as a reaction against an eastern practice

which was spreading in the west, and of which the Breton conhospitae provide

evidence.

78

A second point is the use of portable altars, illustrating ministry

to the population before churches were built in the countryside. Finally, one

gets the impression that the priests were operating on their own, with no effec-

tive episcopal supervision. For the bishops who write do not address Lovocat

and Catihern as though they were ministering within one of their dioceses,

and indeed, the priests’ probable sphere of operation was in the territory of

the Coriosolites; and yet the bishops address them directly, rather than going

through their own diocesan bishop. This may hint at the dislocation of diocesan

structures as a result of the British influx.

79

Dislocation of ecclesiastical structures (if they ever fully existed) certainly

occurred west of the dioceses of Rennes and Vannes, and is matched by a

lacuna in our sources. A synod held at Tours in 567 attempted to outlaw the

consecration of anyone as bishop, whether ‘Briton or Roman’, unless he had

the metropolitan’s consent.

80

This would surely have been unenforceable in the

areas under Breton control. By the mid-ninth century, when evidence becomes

available, we find five episcopal centres in Breton hands. The dioceses of Vannes

75

Pietri and Biarne (1987), pp. 11–16;Duchesne (1910), pp. 245–9;Ch

´

edeville and Guillotel (1984),

pp. 114–15, 142–3;Tanguy (1984). Some scholars regard the Litard, who signed as bishop ‘de Vxuma’

at the Synod of Orl

´

eans in 511,asfrom the Osismii: cf. de Clercq in CCSL, p. 13;Gaudemet and

Basdevant (1989), pp. 90–1;Duchesne (1910), p. 244,n.1.

76

Munier in CCSL, p. 148.

77

J

¨

ulicher (1896), p. 665.

78

Cf. Dani

´

elou (1961), esp. pp. 22–4;Pontal (1989), p. 67 n. 67, and pp. 264–5.

79

Cf. J

¨

ulicher (1896), p. 671.Tanguy (1984), p. 99, suggests that Langu

´

edias (C

ˆ

otes-du-Nord) takes its

name from *Lann-Catihern.

80

Council of Tours 567,c.9: Concilia Galliae, ed. de Clercq (1963), p. 179.