Fouracre P. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500-c. 700

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Religion and society in Ireland 423

one overbishop for each main political overkingdom within Ireland? Further,

does not the evidence for individual churches building up federations, which

might include churches in a different overkingdom, contradict the provincial

model?

Someof these problems can be speedily resolved. First,although both Kildare

and Armagh claimed to be the supreme church in Ireland, the assertions of

Cogitosus and the Liber Angeli are evidence of claims made: not of their claims

being accepted. On the contrary, Liber Angeli is explicit evidence that Armagh

refused to accept Kildare’s claim; and T

´

ırech

´

an, although writing on behalf

of Armagh, openly admits that other churches in Ireland refused to accept its

claims.

124

Confirmation that no single church in Ireland was widely recognised

as being of superior status can be found in the absence of any citations to that

effect in the Irish canonical collection.

125

This, however, does not preclude the

likelihood that Armagh was recognised as the first among equals by the late

seventh century, even in Munster.

126

Until recently, the confusing and sometimes contradictory rulings about

ecclesiastical provinces in the Irish canonical collection were also dismissed as

belonging to the realm of aspiration, not actuality. They are mostly ascribed to

synods of the Roman party, and have been seen as reflecting a failed attempt

by the Romani to impose a continental, hierarchical structure on the Irish

church.

127

Recently, however, attention has been drawn to various pieces of evi-

dence which suggest that these canons should be taken seriously. For instance,

some Irish texts refer to a ‘bishop of bishops’, or ‘supreme noble bishop’, imply-

ing that different rankings of bishops did indeed exist.

128

Even more interesting

are later annalistic obits recording some individuals who were bishops of an

area covering more than one t

´

uath, sometimes a province. However, the role of

‘overbishop’ of a province was not tied to a specific church, as on the continent;

so, for instance, both M

´

ael-M

´

oedh

´

oc of Killeshin (d. 917)and Anmchad of

Kildare (d. 981)are recorded as archbishop or bishop of Leinster.

129

Unfor-

tunately we do not know whether such ‘overbishops’ had a fixed role in a

hierarchical structure, or whether the titles were bestowed on individuals as

a personal honour.

130

Such uncertainties make it difficult to know whether a

124

Liber Angeli, esp. 32;T

´

ırech

´

an, Collectanea c.18.

125

I here follow Charles-Edwards (2000), pp. 424–6; for a contrary view, Etchingham (1999), pp. 155,

160–1.

126

Sharpe (1984c), p. 66;Breatnach (1986), pp. 49–51; Charles-Edwards (2000), p. 426.

127

Sharpe (1984c), pp. 67–8.

128

Etchingham (1999), pp. 72, 156, 162; Charles-Edwards (2000), p. 259.

129

Etchingham (1999), pp. 177–88; Charles-Edwards (2000), pp. 260–1. These show that such titles

belonged to individuals, rather than to a fixed church, much as the provincial overkingship could

also rotate.

130

Cf. Davies (1992), p. 14.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

424 clare stancliffe

coherent system of provincial church organisation, with a hierarchy of levels,

did in fact win general acceptance.

As regards the third type of organisational structure, the federations or

paruchiae, the evidence for these, at least, is convincing. Two further points

should be made about the workings of such federations. First, although depen-

dent churches could be affiliated to a church in a different overkingdom, we

should not regard this as common. The greatest churches, like Armagh, Kildare

and Iona, did indeed have widely scattered churches under them. However, it

was commoner for the majority of dependent churches to be in the neighbour-

hood of the dominant church, as, for instance, with the cluster of churches

affiliated to Cork.

131

Often, then, the ties of province and the ties binding

together a federation of churches will have reinforced each other. Secondly, we

must not assume that whenever a lesser church became in some way linked

to a federation headed by a more powerful church it necessarily lost its own

identity. It so happens that some of our best evidence for the operation of a fed-

eration of churches concerns Iona; and the abbot of Iona did indeed direct the

whole as one community (familia), appointing priors and transferring monks

from one monastery to another.

132

Iona, however, may well have been unusual

in this degree of centralisation; and, most of the time, when one church came

to ‘hold’ a lesser church, we should think of the relationship as essentially an

economic one. The lesser church would owe some form of tribute, whether

this was a symbolic trifle, or an economic burden; but it would generally retain

its own status. Thus an episcopal church could become subject to a monastery,

but remain the episcopal church for the t

´

uath it served – though not in every

case.

133

In conclusion, we may say that the Irish church did have a form of episcopal

organisation, and of groupings into provinces. Cutting across this structure,

however, was the position of the most powerful monasteries, which seem never

to have been effectively controlled by bishops; and this, combined with the

fact that their heads were of the same status as bishops, had many churches

within their paruchiae and controlled the resources of those churches,

134

meant

that these heads were on a par with the most powerful people in the early Irish

church. Thus in 700 Armagh’s power in practice rested upon its prestige, lands,

the number of churches federated to it and the support it could attract from

kings, rather than on the grandiose claims put forward in Liber Angeli; and

131

Hurley (1982), pp. 304–5, 321–3.

132

MacDonald (1985), esp. pp. 184–5;Herbert (1988), pp. 31–5.

133

Hurley (1982), pp. 321–4;Sharpe (1984b), pp. 243–7;(1992a), pp. 97–100, 105–6; Charles-Edwards

(2000), pp. 251–7;cf. Charles-Edwards (1989), p. 36.

134

Sharpe (1984b), pp. 263–4.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Religion and society in Ireland 425

in 700 Adomn

´

an, scholar, head of the Columban federation and – crucially –

fourth cousin of the U

´

ıN

´

eill overking, was probably more influential than the

bishop who headed the Armagh federation. His achievement at the synod of

Birr in 698 testifies to this. Here, he succeeded in promoting a law protecting

clerics, women and children from warfare; and this was guaranteed by mus-

tering dozens of kings and high-ranking churchmen to support it, led by the

bishop of Armagh.

135

This illustrates the potential scope for a great abbot to

provide leadership within the early Irish church.

135

N

´

ıDhonnchadha (1995).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

chapter 16

CHRISTIANITY AMONGST THE

BRITONS, DALRIADAN IRISH

AND PICTS

Clare Stancliffe

BRITAIN SOUTH OF THE CLYDE/FORTH

AND BRITONS ABROAD

The centuries following the end of Roman rule in Britain were critical for

the development of the British church, just as they obviously were for the

determination of the political, ethnic and social structure of Britain as a whole.

However tricky it may be to piece together the picture from the inadequate

and very disparate sources that are available, we must keep in view the major

achievements of these centuries. They saw not merely the consolidation of

Christianity in those areas that remained free from the control of the incoming

pagan Anglo-Saxons, but its spread to areas further north and west. Moreover,

this was achieved despite the demise of the Romano-British cities and villas,

and the Anglo-Saxon settlement of a great swathe of eastern and southern

Britain: precisely those places and areas where the Romano-British church had

been most in evidence. Since interpretations of the post-Roman period often

depend on those of Christianity’s fortunes in Roman Britain, we shall begin

with a brief look at the latter.

the roman prelude

By the time of Constantine I’s conversion to Christianity in the early fourth cen-

tury there were bishops at London, York and (probably) Lincoln.

1

The extent

of Christianity’s progress by 410 is controversial: we lack written evidence, and

the archaeological evidence is open to different interpretations. We cannot

reliably distinguish Christian burials from pagan ones unless there is support-

ive evidence of explicit Christian symbols or inscriptions, as at Poundbury in

Dorset. Christians were generally buried in graves oriented west/east, with no

grave goods, but so might pagans be; and occasionally there is evidence of

1

Mann (1961); cf. Toynbee (1953), pp. 1–4.

426

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Christianity amongst the Britons, Dalriadan Irish and Picts 427

a Christian burial with grave-goods, or oriented differently.

2

Similar problems

can arise with the identification of buildings as Christian churches, as with the

so-called ‘church’ at Silchester.

3

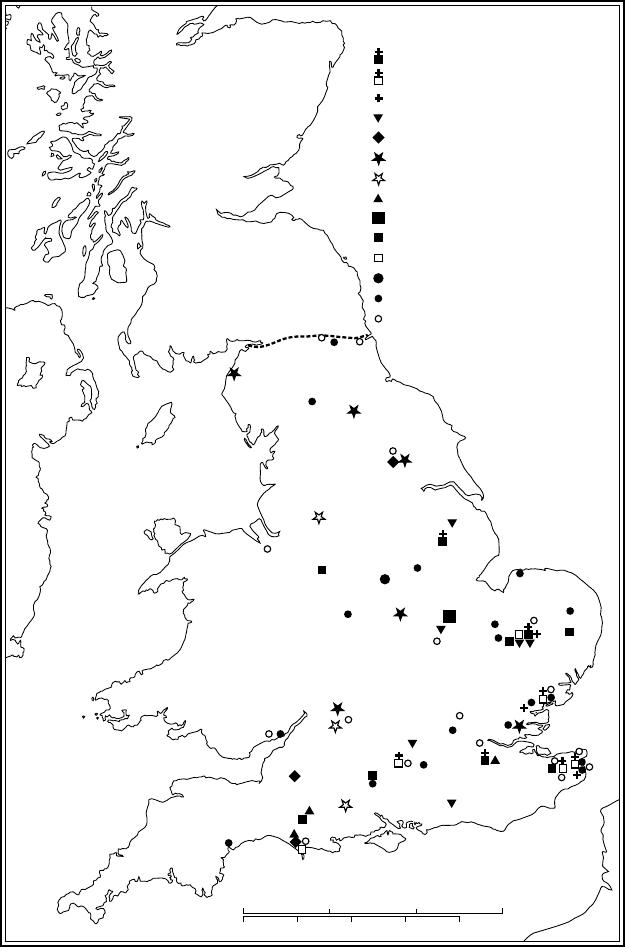

When the more reliable evidence for Christian-

ity is mapped (Map 11), it reveals a significant scatter of evidence down the east

side of Britain from York, southwards; and in the south of Britain this evidence

extends as far west as Dorset. Contrariwise the western counties, and even parts

of the midlands, remain largely blank apart from scattered Christian symbols

on building materials and a few portable finds.

4

We must ask, however, whether

such maps reflect the actual distribution of Christianity in Roman Britain, or

simply the recognisable archaeological evidence for it. One warning signal is

the correlation between the archaeological evidence for Christianity, and that

for ‘acculturation’ or successful Romanisation.

5

Thus archaeology on its own

cannot shed light on whether the population of western Britain was pagan or

Christian.

Awelcome sidelight is provided here by the writings of Patrick, the British

missionary to Ireland. Patrick was probably born at the end of the fourth or

in the first half of the fifth century, and Christianity reached back at least two

generations in his well-to-do family: his father was a deacon, his grandfather a

priest; and since their estate was in an area exposed to Irish raids, it presumably

lay somewhere in western Britain within easy reach of the Irish Sea. Although

Patrick and the others captured with him ‘did not obey our priests’, they were

all at least nominally Christian.

6

This provides welcome confirmation of the

normality of a Christian community in an area where archaeological evidence

is sparse.

Archaeology is, however, valuable in showing the type of place and the class

of people that had embraced Christianity. A generation ago, Romano-British

Christianity was regarded simply as an urban and aristocratic phenomenon.

Archaeology confirms this, most strikingly with the discovery of a church

actually built in the middle of the forum at Lincoln, and with that of

a house-church at Lullingstone villa, Kent.

7

Howeveritalso reveals that

Christianity had reached the Roman fort at Richborough (Kent), and the

small towns, such as Icklingham (Suffolk), Ashton (Northamptonshire) and

Wiggonholt (Sussex).

8

This helps us to understand how Christianity could

have survived in Britain at a time when the collapse of the money economy

2

Rahtz (1977), p. 54;Farwell and Molleson (1993), pp. 137, 236;cf. Watts (1991), pp. 38–98.

3

To ynbee (1953), pp. 6–9;Frere (1976); King (1983).

4

Thomas (1981), pp. 106–7, 138;Morris (1983), p. 16;Watts (1991), pp. 90, 144;Mawer (1995).

5

Jones and Mattingly (1990), pp. 151, 299.

6

Patrick, Confessio 1; Epistola 10.Dumville et al.(1993), pp. 13–18.

7

To ynbee (1953), pp. 9–12;Meates (1979), esp. pp. 18–19, 40–8, 53–7;Jones (1994).

8

Brown (1971); West (1976), p. 121;Morris (1983), p. 18.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

428 clare stancliffe

0

0

50

50

150 miles

100 200 km150

100

Key

probable church

possible church

?baptistery

lead tank with chi-rho

Christian burial

Christian symbol on building material

?Christian symbol on building material

villa, decoration including chi-rho

hoard of church silver

hoard including item(s) with chi-rho

hoard including ?Christian item(s)

single item of church silver

portable find, Christian

portable find, ?Christian

Map 11 Archaeological evidence of Christianity in Roman Britain

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Christianity amongst the Britons, Dalriadan Irish and Picts 429

and sophisticated distribution systems led to the demise of city life and villa

society.

Of course, even where evidence of Christianity is found, it tells us nothing

about the proportion of Christians to pagans, and widely different assumptions

have been made. The most plausible approach is to look at continental parallels,

particularly for the survival of paganism. In Britain, the number of pagan

temples in use appears to have peaked in the mid-fourth century, considerably

later than on the continent. By the late fourth and early fifth centuries, however,

the number of such temples was dropping sharply, albeit not as rapidly as

abroad.

9

By the time that Gildas wrote in the first half of the sixth century, the

implication is that British society was nominally Christian. Gildas castigates

the bishops for failing to denounce sin; but not, we should note, for condoning

paganism.

10

This does not preclude the likelihood that pockets of paganism

remained in the countryside, out of sight of Gildas and the bishops (as indeed

the Life of St Samson implies for Cornwall); but it makes ‘high-profile’ paganism

unlikely.

11

With this background sketched in, we can now turn to a question that has

long intrigued the archaeologists. Archaeological evidence for Christianity in

the Roman period has a predominantly eastern distribution, as we have seen.

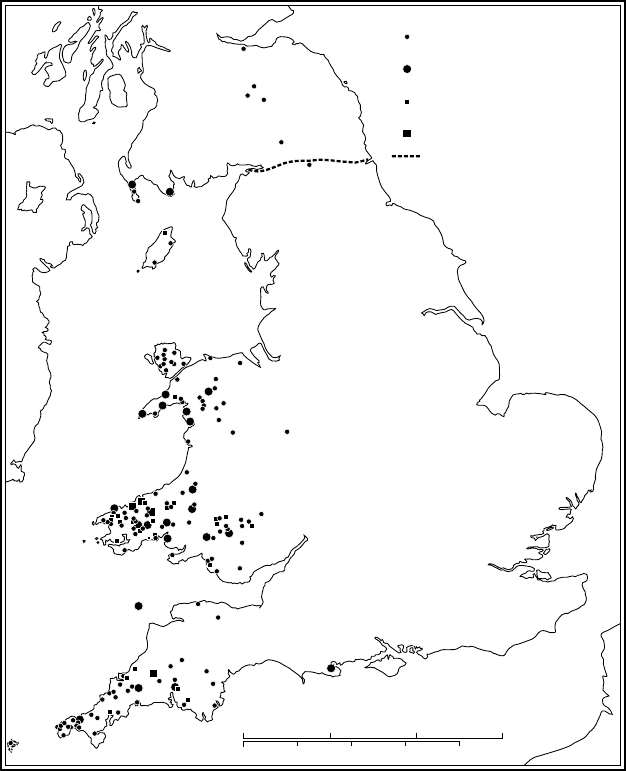

However, a totally different distribution appears on a map of the most tangible

evidence for Christianity in post-Roman Britain: that is, upright stones bear-

ing what are usually interpreted as memorial inscriptions,

12

many of which are

explicitly Christian (Map 12). Most of these date from the fifth to the early

seventh centuries, although a considerably longer time span has recently been

argued for some of those from Dumnonia (Devon and Cornwall). Approx-

imately 150 occur in Wales and another fifty in Dumnonia, while smaller

numbers are found in the Isle of Man and scattered across northern Britain;

some also occur in Brittany.

13

What is striking about this distribution is that

it lies well away from the evidence of Christianity found on our earlier map,

and indeed touches the more Romanised areas only occasionally. Even more

interesting is the fact that the Christian formulas used have no ancestry in

Britain, but can be paralleled on the continent, where the hic iacet (‘Here

lies’) type occurs at Trier in the late fourth century and at Lyons c.420–450,

thereafter giving way to slightly longer formulas such as hic reqviescit

in pace (‘Here rests in peace’).

14

9

SeeP.Horne’s graphs, apud Dark (1994), p. 33.Cf. Salway (1981) and (1984), pp. 734–9.

10

Gildas, De Excidio.

11

Cf. Vita Samsonis cc.3, 48–50;cf. Olson (1989), p. 16.For Yeavering, see Thacker, chapter 17 below.

12

But see Handley (1998).

13

Morris (1983), pp. 28–33, and cf. 20–3;Nash-Williams (1950); Okasha (1993); Thomas (1991–2); and

cf. Thomas (1968); Macalister, Corpus Inscriptionum i and ii Davies et al.(2000).

14

Knight (1981), pp. 57–60, and see now Handley (2001), esp. pp. 186–8;cf. Okasha (1993), pp. 116–21.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

430 clare stancliffe

0

0

50

50

150 miles

100 200 km150

100

Key

stone with inscription in Roman

alphabet, and/or with chi-rho

site with more than one stone with

inscription in Roman alphabet

stone with inscription in both

Roman and ogham alphabets

site with more than one stone

with Roman/ogham inscription

line of Hadrian's Wall

Note: stones bearing inscriptions

only in the ogham alphabet

are not shown

Map 12 Stones with post-Roman inscriptions

How should this disjunction between our two maps be interpreted? A gen-

eration ago a distinguished archaeologist surmised that Christianity in Roman

Britain had been espoused only by the official and commercial elite; and, hav-

ing failed to win over the rural population, had died out along with that elite.

Britain therefore had to be reconverted by missionaries trained on the conti-

nent, who were active up the western seaways – witness the Latin inscriptions –

and were credited with introducing monasticism. The suggested prototype of

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Christianity amongst the Britons, Dalriadan Irish and Picts 431

these was Ninian, whose church at Whithorn, dedicated to the Gallic monk-

bishop St Martin, was the site of inscribed stones; and whose alleged training at

Rome and missionary work among the southern Picts are mentioned – with a

precautionary ‘it is said’ – in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, written perhaps three

centuries later (731).

15

The theory that Christianity wholly died out in Britain has since been con-

vincingly rebutted.

16

None the less, the older model still exerts an influence.

Thus the fact that Anglo-Saxon Kent was converted to Christianity by mission-

aries sent from Rome, and not by an indigenous British church, is sometimes

attributed to the failure of Christianity to establish itself as strongly in Roman

Britain as it did on the continent.

17

Again, the advent of monasticism is still

sometimes portrayed as linked to the western seaways and to the distribution

of at least some of the inscribed stones, and regarded as the true turning-

point between sub-Roman and early medieval Christianity.

18

We will return to

the question of the British church’s alleged failure to convert the Anglo-Saxons

later; in the meantime we shall examine the evidence that prompted the original

theory, and reconsider that for Christianity in sub-Roman and early medieval

Britain, giving special attention to northern and western Britain.

christianity in sub-roman britain: continuity or

cultural break?

The contrast between the map of Romano-British Christianity and that of the

Latin inscriptions on standing stones is at first striking, but we have already seen

that the earlier map represents only evidence for Christianity that is archaeolog-

ically visible. The map of Latin inscriptions similarly needs to be interpreted

aright. The inscriptions are not necessarily all Christian, nor all linked to

Gaul. Some of them have closer parallels with Irish ogham stones (which can

be pagan or Christian);

19

and a link between the two is supplied by the bilingual

(or ‘bi-alphabetical’) inscriptions in South Wales which are recorded in both

the Roman and the ogham alphabets. Where the inscription is recognisably

Christian in form, it clearly attests to Christianity; but we must beware of

the false assumption that the absence of such inscriptions implies the absence

of Christianity. Quite apart from the obvious fact that only the wealthy are

likely to have been so commemorated, we must recognise that the erection

of such memorials is a cultural phenomenon: people in that society chose to

commemorate certain individuals, at least some of them Christian, in that way.

15

Radford (1967) and (1971).

16

Wilson (1966); Thomas (1981), esp. pp. 240–74, 351–2.

17

Frend (1979) and (1992); but see now Stancliffe (1999).

18

Thomas (1981), pp. 347–51.

19

Bullock (1956); Thomas (1994), esp. pp. 67–87;Handley (1998).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

432 clare stancliffe

A hundred and sixty kilometres further east or south, however, the population

might have been equally Christian, but might not have adopted the fashion of

commemorative stone inscriptions.

This can be shown to have been the case if we look at a third map, this

time illustrating the distribution of Eccles place-names (Map 13). These come

from the Vulgar Latin eclesia or its Celtic derivatives, all meaning ‘church’.

Their distribution therefore attests some – though by no means all – of the

places which had churches before the Anglo-Saxon occupation of that area.

20

(Wales and Cornwall have deliberately been left blank not because they have no

such names, but because such place-names continued to be coined long after

the period that concerns us.

21

) This is no place to explore the complexities

of why the survival rate of Eccles place-names is so patchy, though we can

at least note that apart from three instances in the south-east, which may

represent very early borrowings,

22

they occur largely in areas that the Anglo-

Saxons conquered only in the seventh century when they themselves were in

the process of becoming Christianised. In all events, where such place-names

survive, they provide incontrovertible evidence of British Christianity for a

period which is approximately that of the inscribed stones. What is interesting

is that the Eccles place-names largely bridge the geographical gap between

the archaeological evidence for Romano-British Christianity on the one hand,

and the Christian inscriptions of the following centuries on the other. Thus

where western and northern Britain are concerned, although the idea – and

the formulas – of the inscribed stones may have come from overseas, there is

no need to think that Christianity itself did. It could more easily have spread

from adjacent areas within Britain.

This hypothesis of the transmission of Christianity further north and

west within Britain receives confirmation from various sources. Continuity

is perhaps clearest in south-east Wales and the adjoining parts of England,

with Eccleswell near Ross, and with Gildas’ record of the names and burial

places (martyrial shrines?) of two citizens of Caerleon (outside Newport),

who had been martyred in Roman times and were evidently still honoured

at the time of writing (c.530).

23

Christianity in the same general area is

attested in the Life of St Samson,asixth-century saint from South Wales

who ended his days in Brittany, where his Life was written. Its date is

much discussed, but a seventh-century origin is the most plausible, and

20

Jackson (1953), p. 412; Cameron (1968); Gelling (1978), pp. 82–3, 96–9;Barrow (1983). For the

addition to the standard corpus of Eccleshalghforth, attested in 1471 as a field name at Warkworth,

Northumberland, see Beckensall (n.d.), p. 24.

21

Cf. Roberts (1992); Padel (1985), p. 91.

22

Gelling (1978), pp. 82–3.

23

Cameron (1968), p. 89;Gildas, De Excidio x.2;cf. Wendy Davies (1978), pp. 121–59 and (1982),

pp. 141–6;Watts (1991), pp. 76, 126–7.Similarly for central Wales, cf. Knight (1999), p. 137.