Ерус Е.С. All About Arts. Visual Art

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

21

an artist is not appreciated in his lifetime and yet highly prized by the

succeeding generations? 7. The heyday of the Renaissance is to be placed be-

tween the 15th and 16th centuries. Artists began to study anatomy and the

effects of light and shadow, which made their work more life-like. Which great

representatives of the period do you know? 8. What national schools of painting

are usually distinguished in European art? 9. Classicism attached the main

importance to composition and figure painting while romanticism laid stress on

personal and emotional expression, especially in colour and dramatic effect.

What is typical of realism/impressionism/cubism/expressionism/surrealism? 10.

What kinds of pictures are there according to the artist's theme? 11. Artists can

give psychological truth to portraiture not simply by stressing certain main

physical features, but by the subtlety of light and shade. In this respect Rokotov,

Levitsky and Borovikovsky stand out as unique. Isn't it surprising that they

managed to impart an air of dignity and good breeding to so many of their

portraits? 12. Is the figure painter justified in resorting to exaggeration and

distortion if the effect he has in mind requires it? 13. Landscape is one of the

principal means by which artists express their delight in the visible world. Do

we expect topographical accuracy from the landscape painter? 14. What kind of

painting do you prefer? Why?

COLOURS

A

There are an enormous number of words and expressions describing

colours in English. Try to remember and begin to use those of particular

use to you.

VOCABULARY GAME

Student A: You and your partner have been invited to attend a dinner in aid of

charity. It is not an occasion for a suit and an evening dress, but you can't go in

jeans and a T-shirt. Below, for each garment you are going to wear, you are

given a choice of four colours. Choose an outfit for both of you which you think

will look attractive.

For him

jacket:

navy blue

white

dark brown

crimson

trousers:

royal blue

khaki

fawn

sea green

tie:

multi

-

coloured

yellow

bright orange

emerald green

shoes:

reddish

buff

peach

black

22

For her

skirt:

deep blue

russet

lavender

pale blue

blouse:

salmon pink

tangerine

lilac

pearl

jacket:

olive green

mauve

rose

yellowish

tights:

flesh

-

coloured

tan

bright pink

turquoise

shoes:

rust

-

coloured

violet

greeny

-

blue

jet black

Student B: You and your partner are going to decorate two of the rooms in a

flat. From the alternatives below, choose a colour scheme for each room.

The kitchen

ceiling:

pure white

greyish

light green

amber

walls:

brick red

sandy

-

coloured

steel

-

blue

lemon

tiles:

whitish

pit

ch

-

black

shocking

pink

brownish

woodwork:

reddish

-

brown

coffee

-

coloured

smokey

-

grey

scarlet

The bedroom

ceiling:

brilliant

white

off

-

white

lime green

sky blue

walls:

copper

dazzling

white

beige

chocolate

woodwork:

purple

cream

-

coloured

bronze

stra

w

-

coloured

carpet:

mottled blue

and green

golden

maroon

charcoal grey

curtains:

bottle green

silvery grey

indigo

gingery red

VOCABULARY PRACTICE

1. Colours love to be used idiomatically. Complete each sentence with the

appropriate colour.

1. He was ... with envy as he watched his friend riding his new bike.

2. When his father told him later he couldn't have a new bike, he went... with

rage.

3. I'm all... and ... after being in that crowded underground train for half an

hour.

23

4. The student went as ... as a beetroot when the lecturer gave her one of his

famous ... looks.

5. You can be sure to find quite a few ... movies in that... light district.

6. I can't really believe that Nero was as ... as he is painted.

7. I felt sorry for those ... recruits, getting Sergeant 'Squash 'em' Sanders on

their first day.

8. You're ...! You're just afraid of what your wife will do to you if you do.

9. I feel so ... when I see you, hand-in-hand with another man.

10. My fingers were ... with cold and I imagine my face was as ... as a sheet.

11. I'll need your resignation in ... and ... of course.

12. She came out of that... comedy about making pies from murder victims

with her face a ghastly shade of….. .

13. You've got to stop looking at the world through ... tinted spectacles, stop

considering these matters in terms of... and .... and start realising there's a huge

... area in between.

14. My father-in-law was hundreds of pounds in the ... after paying for our

splendid ... wedding.

2. Each of the following concepts can be expressed with a word or phrase

that includes the colour given. Match the concept with the appropriate

idiom.

a black sheep a black leg a blacklist the black market

1) a person who refuses his union's instructions to strike;

2) a member of the family who fails to live up to the others' standards;

3) illegitimate trading, perhaps of goods in short supply;

4) a number of people under suspicion, or in danger of unfavourable treatment

the red carpet a red-letter day caught red-handed red-tape

1) caught in the act, in the middle of a crime;

2) a special, very important occasion

3) an excessive amount of bureaucracy

4) a very special welcome for a very special guest

out of the blue blue-collar workers someone with blue blood once in

a blue moon

1) very, very rarely;

2) suddenly and unexpectedly;

24

3) those doing manual, not clerical or administrative work;

4) someone of noble birth, an aristocrat

B

LISTENING

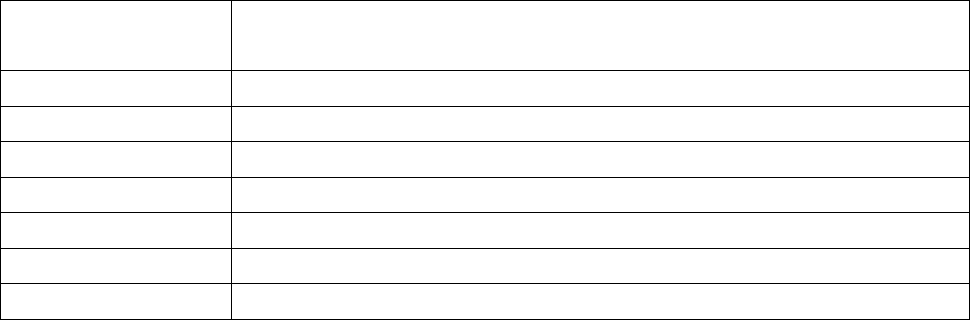

1. Listen to a TV interviewer talking to a home design expert. Make notes

about the colours in this table. What positive or negative emotions are

associated with the colours? Which rooms are they good/not good for?

Colour

It’ s good for … because ...

Red

Purple

Pink

Blue

Yellow

Brown

Black

2. Listen again to the TV interview. For questions 1-7, choose the best

answer (А, В or C).

1. What is the first thing many of us think about when we decorate?

A the layout of the room

В the contents of the room

С the colour scheme of the room

2. What does Laurence say colour tells a visitor?

A the mood we are in

В the sort of person we are

С whether they will like you

3. What does Laurence think about the choice of colours these days?

A there aren't enough of them

В that people still tend to prefer white or pale colours

С people find it hard to choose

4. What don't people often think of when they choose a paint colour?

A whether everything in the room will match

В whether they will be able to relax with it

С that some colours are no longer fashionable

25

5. How do interior designers appear to know what to do?

A through following strict rules of design

В through doing courses

С through natural talent and experience

6. What kind of colours do you need for rooms facing?

A dark

В pale

С bright

7. In order to learn more, Laurence recommends that

A experiment with colour and do what feels right.

В hire a decorator.

С always follow the rules of colour.

C

You are going to read an article about the medical condition synesthesia.

For questions 1-8, choose the answer (А, В, С or D) which you think fits

best according to the text.

1. What happens to people with synesthesia?

A They cannot see certain colours.

В They do not see things in the same way as other people.

С They have problems with counting and numbers.

D They are unable to taste and smell most things.

2. What do experts think about synesthesia?

A It is an illness.

В It is imaginary.

С It does not really exist.

D It is possible to prove.

3. How quickly do synesthetes see the triangle in Ramachandran and Hubbard's

picture?

A Very quickly.

В Very slowly.

С The same speed as 'normal' people.

D They cannot find the triangle.

4. What colour do synesthetes see the number 4?

A Different synesthetes will see a different colour.

В Most synesthetes think it is orange.

26

С Most synesthetes think it is green.

D For most synesthetes the colour is constantly changing.

5. What kind of colours do synesthetes see when they look at numbers?

A Vague colours.

В Unpleasant colours.

С Very precise colours.

D Very basic colours.

6. How do many artists feel about their synesthesia?

A They feel depressed.

В They feel frightened.

С It has been a major problem in their life.

D They think it has been beneficial.

7. It is likely that a synesthete knows someone else with the condition because

A a large percentage of people have it.

В people in the same family often have it.

С most people know they have the condition and they tell other people about it.

D it is very common nowadays.

8. How many synesthetes associate the same number with the same colour after

a year?

A all of them

В about half of them

С the same number as ordinary people

D the minority of them

Wednesdays are red, but Mondays are green

Look at the numbers at the top of the page. What colours do you see?

Probably none as the numbers are all in black and white, but there is a small

group of people who would see these numbers in many different colours.

These people have the condition synesthesia, which means that their five

senses react to things in unusual ways. When they hear a sound, they may see

a colour. When they touch something, they may smell something too – and

smell something that no one else can. These people, synesthetes, see, hear,

smell and touch things that other people do not. When they see a number, like

those at the top of this page, they may see a colour. They may also associate

colours with days of the week so that Wednesdays are red and Mondays are

green. And this condition is not that rare: experts believe that 1 in 2,000

people are synesthetes.

27

There is an argument that synesthesia is just imagination, that it is not real.

But two scientific researchers, Ramachandran and Hubbard have proved that it

does exist.

They use a picture with five examples of the number 2 mixed up with lots

of examples of the number 5, because the two figures look very similar. The

examples of number 2 were all placed in the shape of a triangle.

When the picture was shown to synesthetes, they instantly saw the triangle

made out of the number 2. Most people can only find the triangle by checking

every number in the picture.

The strange thing is that synesthesia is different for everyone. So one

synesthete may say that 4 is blue, and another might say that it is orange. Even

more strange is that synesthetes do not just say that the number is red or green:

they actually give a detailed description of the colour, such as 'tomato red' or

'lime green'. So is synesthesia a form of madness? The answer is simple: no.

Most synesthetes lead normal lives and often do not know that they see the

world differently to other people. Interestingly, many writers, composers

and artists have been synesthetes and they credit it with being an inspiration in

their work. For many of these people, their artistic life would have been very

different if they had not had the condition. Indeed, now that more is known

about it, scientists and historians are hypothesising about historical figures who

may have been synesthetes.

So finally, how do the experts discover if someone is a synesthete? Firstly,

many people with the condition are female, left-handed, and of normal, or

higher than normal, intelligence. They possibly have relatives with the

condition, as it is genetic. In addition to this, although there are hundreds of

different forms of synesthesia, those who associate colours to numbers 65

always associate the same colour with the same number. In tests held in 1993,

non-synesthetes did not connect the same colour with a number after one week.

Every one of the synesthetes could still identify the same colour with the same

number twelve months later.

DISCUSSION

Which of the following do you prefer? Why?

sunrise or sunset?

April or October?

black and white photos or colour ones?

pastel colours in rooms or strong, bright colours?

paintings by six-, eleven- or sixteen-year-olds?

28

UNIT 3

TRENDS OF PAINTING

A trend of painting - an artistic movement which is characterized by a

certain subject-matter, a particular technique and a special coulour-scheme

which developed within certain time-frames and had its own representatives.

Read the following text and give titles to its parts:

IMPRESSIONISM

1

If we look at the bottles in "A Bar at the Folies-Bergère" by Manet, we

shall notice that the treatment of detail here is totally different from the

treatment of detail by the painters of the Academy who looked at each leaf,

flower and branch separately and set them down separately on canvas like a

sum in addition. But all the bottles in Manet's picture arc seen simultaneously in

relation to each other: it is a synthesis, not an addition. Impressionism then, in

the first place, is the result of simultaneous vision that sees a scene as a

whole, as opposed to consecutive vision that sees nature piece by piece.

Monet's picture "The Church at Vernon" shows us what we should sec at the

first glance; the glance, that is to say, when we see the scene as a whole,

before any detail in it has riveted our attention and caused us unconsciously

to alter the focus of our eye in order to see that detail more sharply.

Another way of putting the matter is to say that in an Impressionist picture there

is only one focus throughout, while in an academic picture there is a different

focus for every detail. These two methods of painting represent different ways

of looking at the world, and neither way is wrong, only whereas the

academician looks particularly at a series of objects, the Impressionist looks

generally at the whole.

2

This way of viewing a scene broadly, however, is only a part of

Impressionism. It was not a new invention, for Velasquez saw and painted

figures and groups in a similar way, therefore Impressionists like Whistler and

Manet (in his earlier works) were in this respect developing an existing tradition

rather than inventing a new one. But a later development of Impressionism,

which was a complete innovation, was the new palette they adopted. From

the time of Daubigny, who said, "We never paint light enough", the more

29

progressive painters had striven to make the colours in their pictures closer to

the actual hues of nature. Delacroix was one of the pioneers in the analysis

of colour. When he was in Morocco he wrote in his journal about the shadows

he had seen on the faces of two peasant boys, remarking that while the sallow,

yellow-faced boy had violet shadows, the red-faced boy had green shadows.

Again, in the streets of Paris Delacroix noticed a black and yellow cab, and

observed that, beside the greenish-yellow, the black took on a tinge of the

complementary colour, violet. Every colour has its complementary, that is to

say, an opposing colour is evoked by the action of the human eye after we have

been gazing at the said colour; consequently all colours act and react on one

another. Delacroix discovered that to obtain the full brilliance of any given hue

it should be flanked and supported by its complementary colour.

The nineteenth was a scientific century during which great additions were

made to our knowledge of optics. The French scientist Chevreuil wrote a

learned book on colour, which was studied with avidity by the younger painters.

It became clear to them that colour was not a simple but a very-complex matter.

For example, we say that grass is green, and green is the local colour of grass,

that is to say, the colour of grass at close range, when we look down on it at our

feet. But grass-covered hills seen at a great distance do not appear green, but

blue. The green of their local colour is affected by the veil of atmosphere

through which we view it in the distance, and the blue we see is an example

of atmosphere colour. Again, the local colour of snow is white, but everybody

who has been to Switzerland is familiar with the "Alpine glow" when the snow-

clad peaks of the mountains appear a bright copper colour owing to the rays

of the setting sun. This "Alpine glow" is an example of illumination colour, and

since the colour of sunlight is changing throughout the day, everything in nature

is affected by the colour of the light which falls upon it.

The landscape painter, then, who wishes to reproduce the actual hues of

nature, has to consider not only "local colour", but also "atmospheric colour"

and "illumination colour", and further take into consideration "complementary

colours". One of the most important discoveries made by the later Impressionist

painters was that in the shadows there always appears the complementary

colour of the light. We should ponder on all these things if wish to realise the

full significance of Monet's saying, "The principal person in a picture is light".

3

This new intensive study of colour brought about a new palette and a

new technique. For centuries all painting had been based on three primary

colours: red, blue and yellow, but science now taught the painters that though

these might be primary colours in pigment, they were not primary colours in

light. The spectroscope and the new science of spectrum-analysis made them

30

familiar with the fact that white light is composed of all the colours of the

rainbow, which is the spectrum of sunlight. They learnt that the primary

colours of light were green, orange-red, blue-violet, and that yellow -though

a primary in paint was a secondary in light, because a yellow light can be

produced by blending a green light with an orange-red light. On the other

hand green, a secondary in paint because it can be produced by mixing

yellow with blue pigment, is a primary in light. These discoveries

revolutionised their ideas about colour, and the Impressionist painters

concluded they could only hope to paint the true colour of sunlight by

employing pigments which matched the colours of which sunlight was

composed, that is to say, the tints if the rainbow. They discarded black

altogether, for, modified by atmosphere and light, they held that a true

black did not exist in nature, the darkest colour was indigo, dark green, or a

deep violet. They would not use a brown, but set their palette with indigo,

blue, green, yellow, orange, red, and violet, the nearest colours they could

obtain to the seven of the solar spectrum.

4

Further, they used these colours with as little mixing as possible. Every

amateur in water-colour knows that the more he mixes his paints, the more

they lose in brilliancy. The same is true of oil paints. By being juxtaposed

rather than blended, the colours achieved a scintillating fresh range of

tones - the high-keyed radiance of daylight rather than the calculated

chiaroscuro of the studio. And the transmission of light from the canvas is

greatly increased. The Impressionists refrained, therefore, as much as

possible from mixing colours on heir palettes, and applied them pure in

minute touches to the canvas. If they wanted to render secondary or tertiary

colours, instead of mixing two or three pigments on the palette, they would

secure the desired effect by juxtaposed touches of pure colours which, at

a certain distance, fused in the eye of the beholder and produced the effect

of the tint desired. This device is known as optical mixture, because the

mixing is done in the spectator's eye. Thus, whereas red and green pigment

mixed on a palette will give a dull grey, the Impressionists produced a

brilliant luminous grey by speckling a sky; say, with little points of yellow

and mauve which at a distance gave the effect of a pearly grey. It was an

endeavour to use paints as if they were coloured light.

To the Impressionists shadow was not an absence of light, but light of a

different quality and of different value. In their exhaustive research into the true

colours of shadows in nature, they conquered the last unknown territory in the

domain of Realist Painting.

To sum up, then, it may be said that Impressionist Painting is based on two

great principles: