Endo M., Iijima S., Dresselhaus M.S. (eds.) Carbon nanotubes

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

178

U.

ZIMMERMAN

et

at.

ber of electrons bonded by

SO2

and

0.

What effect

does C60 as an impurity have on the electronic shell

structure? Will it merely shift the shell closings by

6

(the number of electrons possibly transferred to the

c60

molecule)? We will investigate this in the follow-

ing paragraphs.

Up to this point, we have always studied the clus-

ters using brute force (i.e., heating them

so

strongly

that they evaporate atoms). But the electronic shell

structure of clusters can also be investigated more gen-

tly by keeping the photon flux low enough to prevent

the clusters from being heated and using photon en-

ergies in the vicinity of the ionization energy

of

the

clusters.

The ionization energy

of

alkali metal clusters

os-

cillates with increasing cluster size. These oscillations

are caused by the fact that the s-electrons move almost

freely inside the cluster and are organized into

so-

called shells. In this respect, the clusters behave like

giant atoms.

If

the cluster contains just the right num-

ber of electrons to fill a shell, the cluster behaves like

an inert gas atom (Le., it has a high ionization energy).

Howeve?, by adding just one more atom (and, there-

fore, an additional s-electron), a new electronic shell

must be opened, causing a sharp drop in the ioniza-

tion energy. It is a tedious task to measure the ioniza-

tion energy of each of hundreds of differently sized

clusters. Fortunately, shell oscillations in the ioniza-

tion energy can be observed in a much simpler exper-

iment. By choosing the wavelength

of

the ionizing light

so

that the photon energy is not sufficient

to

ionize

closed-shell clusters, but is high enough

to

ionize open-

shell clusters, shell oscillations can be observed in a

single mass spectrum. Just as in the periodic table

of

elements, the sharpest change in the ionization energy

occurs between a completely filled shell and

a

shell

containing just one electron. In a threshold-ionization

mass spectrum this will be reflected

as

a

mass peak

of

zero intensity (closed shell) followed by

a

mass peak

at high intensity (one electron in

a

new shell). This be-

havior is often seen. However, it is

not

unusual to find

that this step in the mass spectrum is ‘washed out’ for

large clusters due to the fact that the ionization thresh-

old of a single cluster is not perfectly sharp.

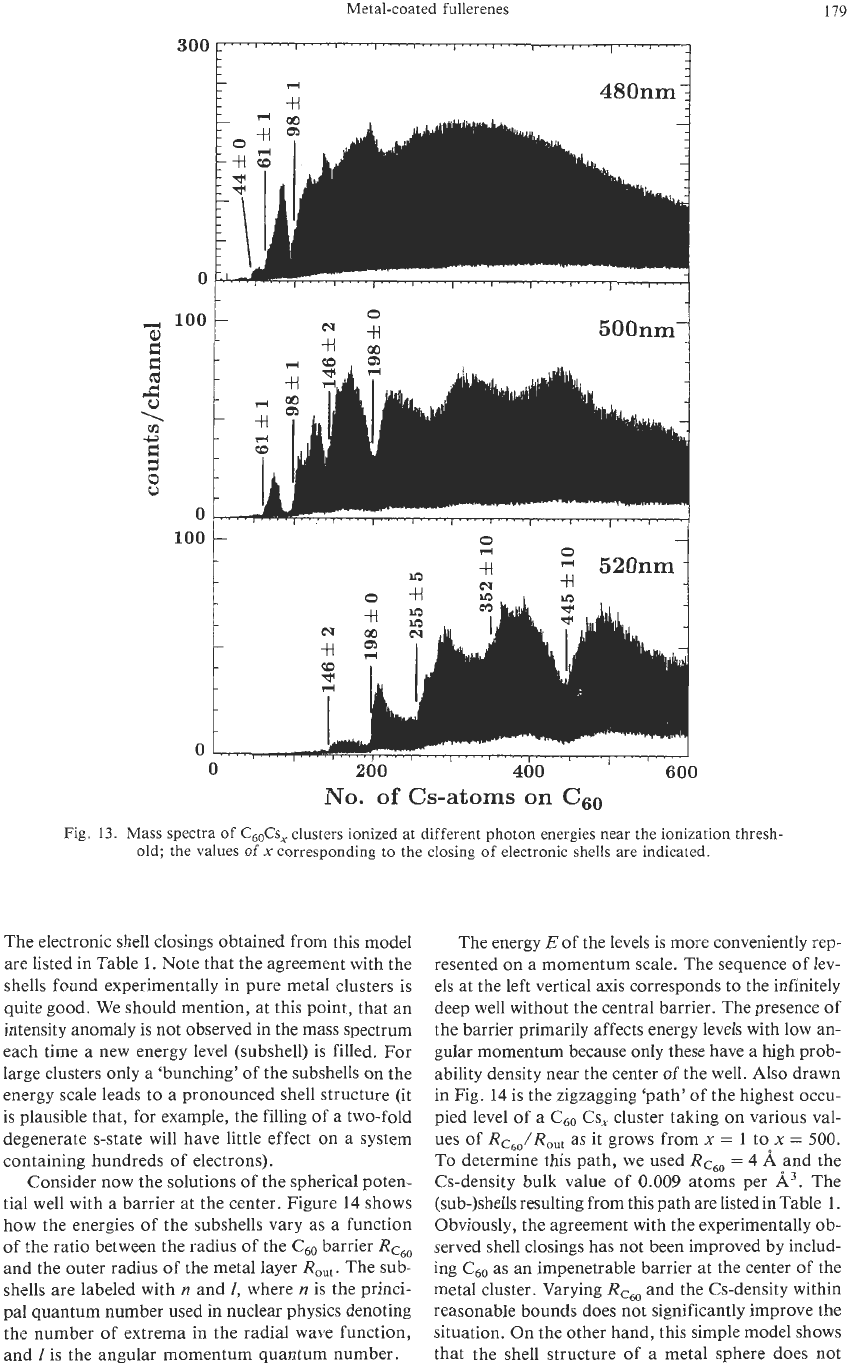

Figure

13

shows a set of spectra of C60Cs, clusters

for three different wavelengths of the ionizing laser.

Note the strong oscillations in the spectra. Plotted on

a

n1’3

scale, these oscillations occur with an equal

spacing. This is a first hint that we are dealing with

a shell structure. Because this spacing is almost iden-

tical to the one observed in pure alkali metal clusters,

these oscillations are most certainly due to electronic

rather than geometric shells. The number

of

atoms at

which the shell closings occur are labeled in Fig.

13

and listed in Table

1.

Note that these values do not

correspond to the minima in the spectra as long as

these have not reached zero signal.

Also listed in Table

1

are the shell closings observed

in pure alkali metal clusters[9,21,23]. These values and

the ones observed for the Cs-covered

Cm

have been

arranged in the table in such

a

way as to show that

there is some correlation between the two sets of num-

bers, but no exact agreement. If we make the simpli-

fying assumption that six Cs atoms transfer their

valence electrons to the

c60

molecule and that these

electrons will no longer contribute to tne sea of quasi-

free electrons within the metal portion of the cluster,

the number

6

should be subtracted from the shell clos-

ings observed for metal-coated

c60.

This improves

the agreement between the two sets of shells. How-

ever, it is really not surprising that the agreement is

still not perfect, because

a

c60

molecule present in

a

metal cluster will not only bond

a

fixed number

of

electrons but will also act as

a

barrier for the remain-

ing quasi-free metal electrons. Using the bulk density

of

Cs,

a spherical cluster Cs,,, has

a

radius

of

ap-

proximately

24

A.

A

Cm

molecule with

a

radius of

approximately

4

A

should, therefore, constitute

a

bar-

rier of noticeable size.

To

get some idea

of

the effect

such a barrier has

on

the shell closings, let us consider

the following simple model.

The metal cluster will be modeled as an infinitely

deep spherical potential well with the C60 represented

by an infinitely high spherical barrier. Let us place this

barrier in the center of the spherical cluster to simplify

the calculations. The simple Schrodinger equation,

containing only the interaction of the electrons with

the static potential and the kinetic energy term and ne-

glecting any electron-electron interaction, can then be

solved analytically, the solutions for the radial wave

functions being linear combinations

of

spherical Bessel

and Neumann functions.

Such

a

simple model, without the barrier due to the

c60

at

the center, has been used

to

calculate the elec-

tronic shell structure

of

pure alkali metal clusters[9].

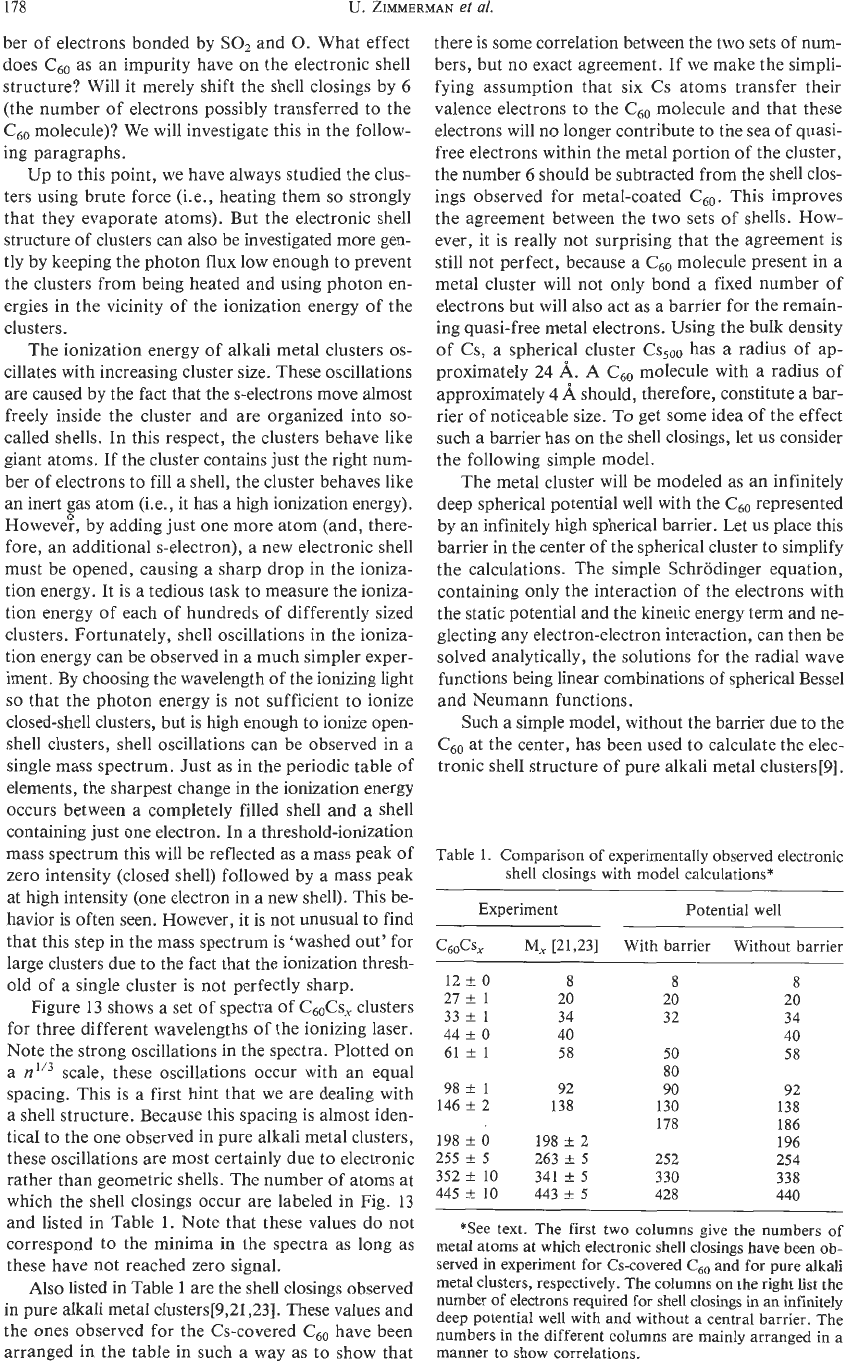

Table

1.

Comparison

of

experimentally observed electronic

shell closings with model calculations*

-

Experiment Potential well

c6@,

M,

[21,23]

With barrier Without barrier

12

f

0

8

8

8

27

f

1

20

20 20

33

f

1

34 32 34

44

f

0

40 40

61

f

1

58

50

58

98

*

1

92 90 92

146

f

2

138 130 138

178 186

198

i

0

198

i2

196

255

f

5

263

f

5

252

254

352

f

10 341

f

5

330 338

445

f

10

443

a

5

428

440

80

*See text. The first two columns give the numbers

of

metal atoms

at

which electronic shell closings have been ob-

served in experiment

for

Cscovered C,, and for pure alkali

metal clusters, respectively. The columns on the right list the

number

of

electrons

required

for

shell closings in

an

infinitely

deep potential well with and without a central barrier. The

numbers in the different columns are mainly arranged in a

manner to show correlations.

Metal-coated fullerenes

179

i

500nm

1

0

rl

0

rl

520nm

ii

-ti

N

v)

200

400

600

No.

of

Cs-atoms

on

C60

0

0

Fig.

13.

Mass spectra of

C&s,

clusters ionized at different photon energies near the ionization thresh-

old; the values

of

x

corresponding to the closing

of

electronic shells are indicated.

The electronic shell closings obtained from this model

are listed in Table

I.

Note that the agreement with the

shells found experimentally in pure metal clusters is

quite good. We should mention, at this point, that an

intensity anomaly is not observed in the mass spectrum

each time a new energy level (subshell) is filled. For

large clusters only a ‘bunching’

of

the subshells on the

energy scale leads to a pronounced shell structure (it

is plausible that, for example, the filling of a two-fold

degenerate s-state will have little effect on a system

containing hundreds of electrons).

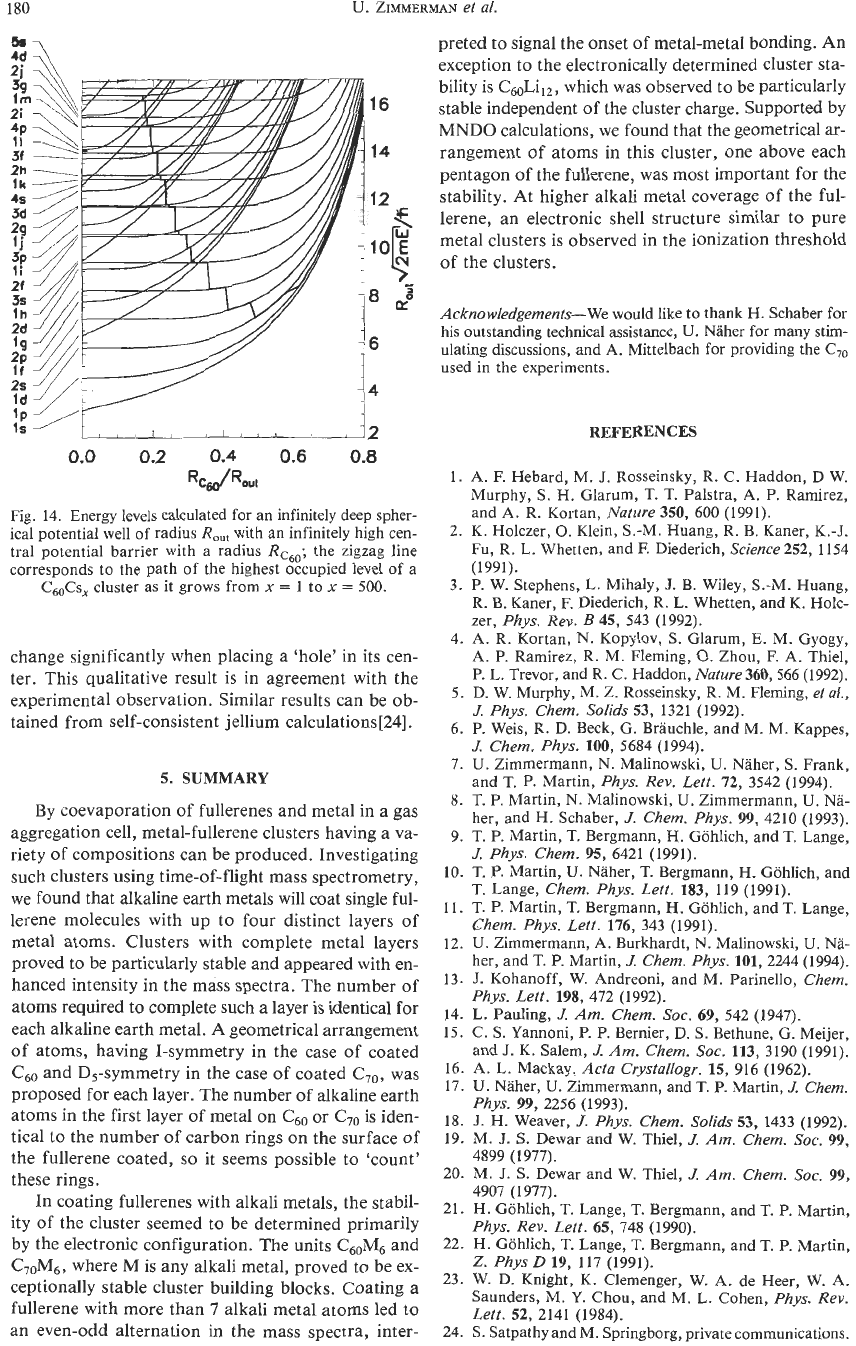

Consider now the solutions

of

the spherical poten-

tial well with a barrier at the center. Figure

14

shows

how the energies of the subshells vary as a function

of the ratio between the radius of the

C60

barrier

RC60

and the outer radius

of

the metal layer

R,,,.

The sub-

shells are labeled with

n

and

1,

where

n

is the princi-

pal quantum number used in nuclear physics denoting

the number

of

extrema

in

the radial wave function,

and

I

is

the angular momentum quantum number.

The energy

E

of

the levels is more conveniently rep-

resented on a momentum scale. The sequence

of

Iev-

els at the left vertical axis corresponds to the infinitely

deep well without the central barrier. The presence

of

the barrier primarily affects energy levels with low an-

gular momentum because only these have a high prob-

ability density near the center of the well. Also drawn

in Fig.

14

is the zigzagging ‘path’ of the highest occu-

pied level of

a

C60

Cs,

cluster taking on various val-

ues of

Rc,/R,,,

as it grows from

x

=

1

to

x

=

500.

To determine this path, we used

RC6,,

=

4

A

and the

Cs-density bulk value

of

0.009

atoms per

A3.

The

(sub-)shells resulting from this path are listed in Table

1.

Obviously, the agreement with the experimentally

ob-

served shell closings has not been improved by includ-

ing

C60

as an impenetrable barrier at the center of the

metal cluster. Varying

RCW

and the Cs-density within

reasonable bounds does not significantly improve the

situation. On the other hand, this simple model shows

that the shell structure

of

a metal sphere does not

180

U.

ZIMMERMAN

et ai.

IS’

I,,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, ,

,

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

RCJR0.t

Fig.

14.

Energy levels calculated for an infinitely deep spher-

ical potential well of radius

R,,,

with an infinitely high cen-

tral potential barrier with a radius

Rc6,;

the zigzag line

corresponds to the path

of

the highest occupied level

of

a

C,Cs,

cluster as it grows from

x

=

1

to

x

=

500.

change significantly when placing a ‘hole’ in its cen-

ter. This qualitative result is in agreement with the

experimental observation. Similar results can be ob-

tained from self-consistent jellium calculations[%].

5.

SUMMARY

By

coevaporation of fullerenes and metal in a gas

aggregation cell, metal-fullerene clusters having a va-

riety of compositions can

be

produced. Investigating

such clusters using time-of-flight mass spectrometry,

we found that alkaline earth metals will coat single ful-

lerene molecules with up to four distinct layers of

metal atoms. Clusters with complete metal layers

proved to be particularly stable and appeared with en-

hanced intensity in the mass spectra. The number

of

atoms required to complete such

a

layer

is

identical for

each alkaline earth metal.

A

geometrical arrangement

of

atoms, having I-symmetry in the case

of

coated

c60

and D,-symmetry

in

the case of coated

C,,,

was

proposed for each layer. The number

of

alkaline earth

atoms

in

the first layer

of

metal on

c60

or

C70

is iden-

tical

to

the number

of

carbon rings

on

the surface

of

the fullerene coated,

so

it

seems possible

to

‘count’

these rings.

In coating fullerenes with alkali metals, the stabil-

ity of the cluster seemed to be determined primarily

by the electronic configuration. The units C&i6 and

C7oM6, where M is any alkali metal, proved

to

be ex-

ceptionally stable cluster building blocks. Coating

a

fullerene with more than

7

alkali metal atoms led to

an even-odd alternation in the mass spectra, inter-

preted to signal the onset

of

metal-metal bonding.

An

exception to the electronically determined cluster sta-

bility is C60Li12, which was observed to be particularly

stable independent of the cluster charge. Supported by

MNDO calculations, we found that the geometrical

ar-

rangement of atoms in this cluster, one above each

pentagon of the fullerene, was most important for the

stability. At higher alkali metal coverage of the ful-

lerene, an electronic shell structure similar

to

pure

metal clusters

is

observed in the ionization threshold

of

the clusters.

Acknowledgements-We

would like to thank H. Schaber for

his

outstanding

technical

assistance, U. Naher for many

stim-

ulating discussions, and A. Mittelbach

for

providing the

C,,

used in the experiments.

REFERENCES

1.

A.

E

Hebard, M.

J.

Rosseinsky, R. C. Haddon, D W.

Murphy,

S.

H.

Glarum,

T.

T.

Palstra,

A.

P.

Ramirez,

and

A.

R. Kortan,

Nature

350,

600

(1991).

2.

K. Holczer,

0.

Klein, S.-M. Huang, R. E. Kaner,

K.4.

Fu, R.

L.

Whetten, and

E

Diederich,

Science

252,

1154

(1991).

3.

P.

W. Stephens,

L.

Mihaly,

J.

B. Wiley,

S.-M.

Huang,

R. B. Kaner,

E

Diederich, R.

L.

Whetten, and K. Holc-

zer,

Phys. Rev. B

45,

543 (1992).

4.

A.

R. Kortan, N. Kopylov,

S.

Glarum,

E.

M. Gyogy,

A.

P. Ramirez, R. M. Fleming,

0.

Zhou,

E

A. Thiel,

P.

L.

Trevor, and R.

C.

Haddon,

Nature

360,566 (1992).

5.

D.

W. Murphy, M.

Z.

Rosseinsky, R. M. Fleming,

eta/.,

J.

Phys. Chem. Solids

53,

1321 (1992).

6.

P.

Weis, R. D. Beck, G. Brauchle, and

M.

M.

Kappes,

J.

Chem. Phys.

100,

5684 (1994).

7.

U.

Zimmermann,

N.

Malinowski,

U.

Naher, S. Frank,

and

T.

P.

Martin,

Phys. Rev. Lett.

72, 3542 (1994).

T.

P. Martin,

N.

Malinowski,

U.

Zimmermann,

U.

Na-

her, and H. Schaber,

J.

Chem. Phw.

99.

4210 (1993).

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

T.

P.

Martin,

T.

Bergmann, H. Gohlich, and T. Lange,

J.

Phys. Chem.

95,

6421 (1991).

T.

P.

Martin, U. Naher, T. Bergmann, H. Gohlich, and

T.

Lange,

Chem. Phys. Lett.

183,

119 (1991).

T. P.

Martin,

T.

Bergmann, H. Gohlich, and

T.

Lange,

Chem. Phys. Lett.

176, 343 (1991).

U.

Zimmermann,

A.

Burkhardt,

N.

Malinowski,

U.

Na-

her, and

T.

P. Martin,

J.

Chem. Phys.

101, 2244 (1994).

J.

Kohanoff,

W.

Andreoni, and M. Parinello,

Chem.

Phys. Lett.

198,

472 (1992).

L. Pauling,

J.

Am. Chem.

SOC.

69,

542 (1947).

C.

S.

Yannoni,

P. P.

Bernier, D.

S.

Bethune, G. Meijer,

and

J.

K. Salem,

J.

Am.

Chem. Soc.

113, 3190 (1991).

A.

L. Mackay,

Acta Crystallogr.

15, 916 (1962).

U. Naher,

U.

Zimmermann, and T.

P.

Martin,

J.

Chem.

Phys.

99,

2256

(1993).

J.

H.

Weaver,

J.

Phys. Chem.

Solids

53,

1433 (1992).

M.

J.

S. Dewar and W. Thiel,

J.

Am. Chem.

SOC.

99,

4899 (1977).

M.

J.

S.

Dewar and W. Thiel,

J.

Am. Ckem.

SOC.

99,

4907 (1977).

H.

Gohlich,

T.

Lange, T. Bergmann, and

T.

P. Martin,

Phys. Rev. Lett.

65, 748 (1990).

H. Gohlich,

T.

Lange,

T.

Bergmann, and

T.

P.

Martin,

Z.

Phys

D

19, 117 (1991).

W.

D.

Knight,

K.

Clemenger,

W.

A. de Heer, W.

A.

Saunders, M.

Y.

Chou,

and

M.

L.

Cohen,

Phys. Rev.

Lett.

52,

2141 (1984).

S.

Satpathy and M. Springborg, private communications.

SUBJECT

INDEX

acetylene source

15

AFRVI:

see

atomic force microscopy

alkalUalkali earth metals

169

arc plasma, nanotube growth

11

atomic force microscopy

(AFM)

65

band gap

37

band structure

37

buckybundles

see

buclqtubes

buckytubes

149

properties

111

cage forms 77

cahon fibers

87

carbon nanotubes

see

nanotubes; pyrolitic carbon

carbon-carbon intralayer distance

59

catalysis

vapo-grown

1

nanotubes

growth

mechanism

87

nanotubule production

15

single-layer nanotubes

47

chiral nanotubes

27

clusters, metal-fullerenes

169

cobalt nanocrystals

153

cobalt particles

47

coiled carbon nanotubes

87

diameters, Mlerene-scale

15

dekcts

7

1

disordered carbons

129

electric field, nanotube growth

11

electrical properties

47

electrical resistivity

12

1

electron irradiation

163

electronic bands

27

electronic properties

11 1

carbon nanotubes

121

structure

37

electronic shells

169

fiber-reinforced composites

143

fibers

47

structures

65

fullerenes

87

growth pathway

65

metal-coated

169

multi-shell, synthesis

153

nanotubes comparison

15

fundamental parameters

27

geometry

carbon nanotubes

59

metal-coated fullerenes

169

glow discharge, buckybundles

11

1

graphene layers, flexibility

149

graphene model

37

graphite structure

1

graphitic carbon 77

graphitic particles, onion-like

153

helical forms

77

helix angle

59

hemi-toroidal nanostructures

105

high-resolution transmission electron microsopy

(HREM)

1,37, 111, 163

icosahedral layers

169

incomplete bonding defects

7

1

infrared studies

129

interlayer distance

59

iron

nanocrystals

153

knee structures

87

magnetic properties, buckytubes

11

1

magnetoresistance

121

magnetic susceptibility

12 1

mass spectroscopy, metal-coated fullerenes

169

mechanical properties

47,

143

metal particles

47

metal-coated fullerenes

169

molecular dynamics 77

multi-shell fullerenes

163

multi-shell

tubes

65

multi-wall nanotubes 27

nanocapsules

153

nanocones, STM

65

182

Subject Index

nanofibers

87

nanoparticles 153

nanostructures 65, 163

nanotubes

bundles

47

catalytic production 15

coiled

carbon

87

defect structures

7

1

electric effects

11

electronic properties

37,

121

fullerene-scale diameters 15

fullerenes, comparison 15

geometry 59

growth mechanisms

1,

11,65,87

hemi-toroidal networks 105

mechanical properties 143

nanoparticles 153

single-layer

47, 187

STM

65

structural properties

37

thermal properties 143

vibrations, theory of 129

natural resonance

143

nickel filled nanoparticles 153

normal modes 129

onion-like graphitic particles 163

open tips 11

PCNTs

see

pyrolyk carbon nanotubes

pitch angle

59

pyrolitic carbon nanotubes

(PCNTs)

hemi-toroidal networks 105

vapor grown

1

Raman scattering studies 129

rare-earth elements 153

rehybridization defects

7

1

scanning

tunneling

microscopy

(STM)

65,

121

single-layer walls 47

single-wall nanotubes 27

spectroscopy

121

stiffness constant 143

STM

see

scanning tunneling microscopy

strain energy

37

structural properties

37

thermal properties 143

topological defects

7

1

toroidal cage forms

77

toroidal network

1

torus form 77

transport properties, buckytubes

1

11

tubes,

growth

pathways 65

tubule arrays

27

topology

77

vapor growth 65

vapor-grown carbon

fibers

1

vibrational modes 27, 129

AUTHOR

INDEX

Bernaerts,

D.

15

Bethune,

D.

S.

47

Beyers,

R.

47

Burkhardt,

A.

169

Chang,

R.

P.

H.

111

Colbert,

D.

T.

11

Daguerre,

E.

149

Despres,

J.

F.

149

Dravid,

V.

P.

111

Dresselhaus, 6.27

Dresselhaus,

M.

S.

vii,

ix

27

Ebbeson,

T.

W.

71

Eklund,

P.

C.

129

Endo,

M.

vii

1:

105

Fonseca,

A.

IS,

87

Goddard

III,

W.

A.

47

Heremans,

J.

121

Hernadi,

K.

87

Holden,

J.

M.

129

Ihara,

S.

77

Iijimla,

S.

vii

Issi,

J.-P.

121

Itoh,

S.

77

Ivanov,

V.

15

Jishi,

R.

A.

129

Ketterson,

J.

B.

111

Kiang,

C.-H.

47

Kobori,

K.

1

Kroto,

H.

W.

1,

105

Lafdi,

K.

149

Lambin,

P.

15,87

Langer,L.

121

Lin,

X.

W.

111

Lorents,

D.

C.

143

Lucas,

A.

A.

15,87

Malinowski,

N.

169

Martin,

T.

P.

169

Mintmire,

J.

W.

37

Nagy,

J.

B. 15,87

Olk,

C.

H.

121

Ruoff,

R

S.

143

Saito,

R.

27

Saito,

Y.

153

Sarkar,

A.

1, 105

SattIer,

K.

65

Setton,

R.

59

Smalley,

R.

E.

11

Song,

S.

N.

11

1

Takada,

T.

71

Takahashi,

K.

I

Takeuchi,

K.

1

Ugarte,

D.

163

Wang,

X.

K.

11

1

White,

C.

T.

37

Xhang,

X.

B.

15

Zimmerman,

U.

169

183