Dunn Colin E. Biogeochemistry in Mineral Exploration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Whereas some contend that washing should be carried out as a matter of course,

regardless of local conditions, washing with these organic solvents would be onerous,

expensive, potentially hazardous for some toxic solvents such as toluene, and im-

practical to apply to all samples from a large biogeochemical survey. Furthermore, it

can be argued that by removing the surface waxes (see Figs. 3-3 and 4-1 – SEM of

twig surface) an integral part of the plant struc ture is remov ed that may contain

elements secreted from within the plant as well as the less desirable aerosol partic-

ulates. The term ‘less desirable’ is used because in addition to distant sources of

contaminants (i.e., allochthonous) the aerosols may contain particulates from the

microenvironment around a plant (autochthonous) that could be useful for explo-

ration purposes. Gaseous emanations from an orebody (e.g., Hg, F, Br, I) that are

not entirely introduced into a plant via its roots, but de-gas through fractured rock

and from soil, could precipitate on plant surfaces and enhance the biogeochemical

signature of these elements. Therefore, an added signature from locally derived aer-

osol particulates (the ‘autochthonous’ microenvironment) is not necessarily un-

wanted, and can provide geochemical information of value to a survey seeking to

delineate concealed mineral deposits.

Usually, an unknown factor is the degree of contamination from distant sources.

Certainly for samples from around a smelter or other industrial activity the airborne

source needs to be minimized, and a thorough cleaning of the type recommended by

Wyttenbach et al. (1987) and Wyttenbach and Tobler (1988) or one of the other

methods listed below would be warranted.

Chloroform is another organic solvent that can be used for removing surface

waxes. Table 6-I shows analyses of leaves from three samples of mountain alder

(Alnus crispa) that were prepared in the field at the collection site. Each sample was

divided into two portions. One-half was prepared for analysis with no pre-treatment;

the second was stripped of its waxes by swirling in a jar of chloroform, and then air-

dried to evaporate the solvent. The two splits of each sample wer e analysed by INAA

for 35 elements, of which those recording losses from the chloroform treatment,

although not consistent for the three sites, are shown in Table 6-I. The data imply

that losse s were those portions of each element associated with the surface waxes and

cuticles, confirming the results of Wyttenbach and Tobler (1988). Similar tests run on

twigs of balsam fir (Abies balsamea) and white spruce (Picea glauca) did not indicate

loss of these elements, because they comp rise woody tissue devoid of significant

amounts of surface wax.

A simpler alternative to the use of organic solvents is to wash samples in distilled

water to which a little detergent (e.g., Calgon, or an ultrapure dispersant such as

Photoflow

TM

by Kodak) is added to reduce surface tension of adhering particulates.

However, there exists the potential problem that such a procedure may remove

elements of exploration interest, because any rigorous swirling of samples can break

down the outer cells of the plant surfaces and release some elements into the washing

medium. Many surface outgrowths are also the location of various crystals (druses)

and removing these structures could dilute the natural biogeoch emical signature.

152

Sample Preparation and Decomposition

Prolonged washing can damage plant tissue, allowing cell cytoplasm to become hy-

drated and leak into solution and, because it is a differential leaching (cell walls

remain intact) the signature generates a fals e bias.

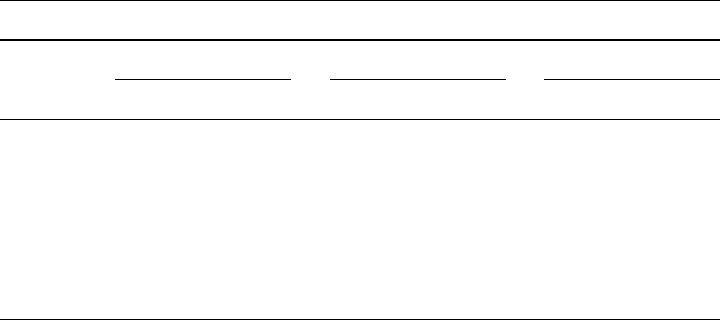

A study by Larry Cook at the University of Idaho (personal communication) has

examined several washing procedures of big sagebrush ( Artemisia tridentata) using

the usually ‘conservative’ (immo bile) element, titanium . W ashing consisted of im-

mersing each sagebrush sample (twigs with leaves) 20 times into the treatment so-

lution and then rinsing with deionized water. Controls were unwashed plants.

Averages for the controls were derived from six replicates and there were three

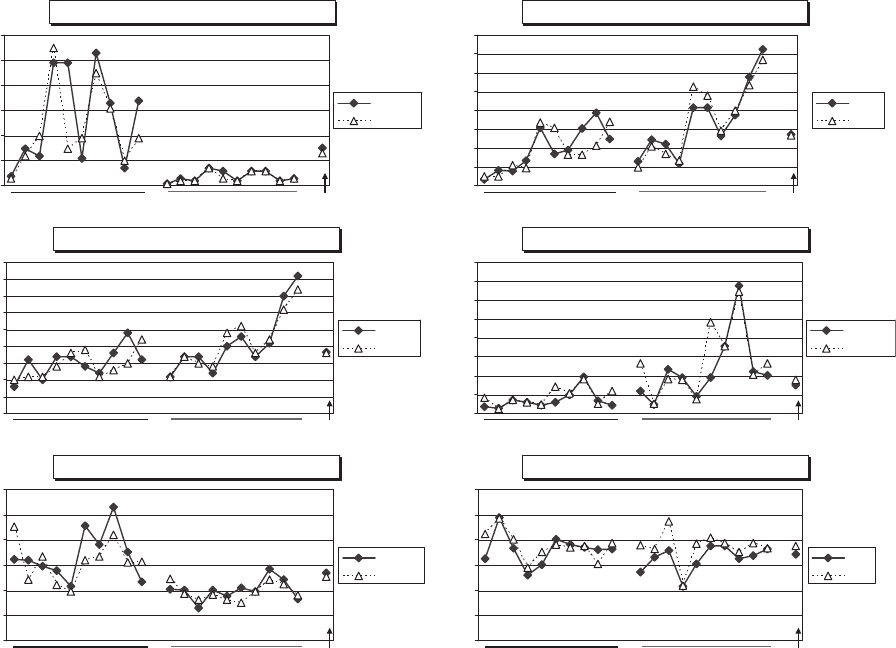

replicates for each of the washing treatment s (Fig. 6-1). The Tween20 and Tween80

products are non-ionic surface wetting/emulsifying agents with differing surfactant

properties. SDS is sodium lauryl sulphate – another wetting agent. The results were

similar for other species that were treated in the same manner, and no one method

emerged as superior in removing soil from plant tissue and none were effective in

removing all adhering particles.

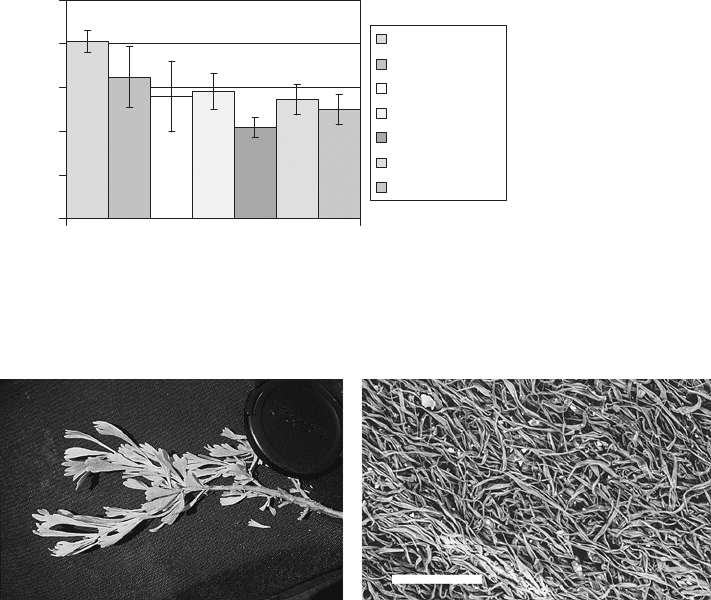

Microscopic examination of big sagebrush shows that it has felted leaves that are

capable of readily trapping airborne particles (Fig. 6-2) and, since the Idaho study

site was described as extremely dusty, the washing removed some, but not all of the

adhering inorganic particulate material. Results of the various washing treatments

show a reduction in Ti content by 20–40% , depending upon the solution. However,

most treatments fell within a close range of about 150 ppm + / 10%, with significant

over-lapping of error bars. In summary, although washing removed some dust, no

method was successful in removing all of the inorganic material.

TABLE 6-I

Analyses of leaves from mountain alder (Alnus crispa) from the La Ronge belt of Saskatch-

ewan – portions untreated, and rinsed with chloroform (‘treated’) to extract waxes and as-

sociated elements. Concentrations in dry tissue determined by INAA

Alder Leaves (Alnus crispa)

Site 1 Site 2 Site 3

Untreated Treated Untreated Treated Untreated Treated

Ca (%) 0.46 0.46 0.50 0.42 0.54 0.49

Ba (ppm) 15 13 20 8 9 13

Zn (ppm) 27 23 18 21 27 22

Fe (%) 0.04 0.02 0.04 0.03 0.02 0.02

Na (ppm) 214 160 245 155 109 97

Cr (ppm) 0.8 0.6 1.0 0.7 0.5 0.3

Th (ppm) 0.11 0.05 0.10 0.10 0.06 0.04

La (ppm) 0.30 0.20 0.37 0.22 0.24 0.22

153Biogeochemistry in Mineral Exploration

In another study on plant washing Azcue and Mudroch (1994) reviewed the

literature, and conducted some experimental work involving 10 trace elements that

compared washing with distilled water, a detergent (Alconox

TM

[1%]), and 1% HCl.

They concluded that the best results were obtained with distilled water.

Washing in water

It is as well to discriminate between rinsing and washing. Rinsing involves simply

passing the sample through a stream of water. Washing is defined here as placing the

sample into a path of liquid where it is submerged for a specified period and/or

agitated. One concern with regard to washing is that the process may lack consist-

ency. For routine washing under controlled conditions, a PreVac

TM

washer could be

used. This controls the quantity and duration of the water treatment and the washing

container is pressurized in a controlled manner. The addition of any other substance

0

50

100

150

200

250

Washing treatments

[Ti], ppm

Control

0.1% Calgon

0.1% EDTA

DI Water

0.1% SDS

0.1% Tween 20

0.1% Tween 80

Fig. 6-1. Results of washing leaf and twig tissues of big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) using

6 different cleaning agents (courtesy of Larry Cook, University of Idaho, 2005). Error bars

represent one standard deviation.

Fig. 6-2. Big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata). Left: typical foliage. Right: SEM showing

felted texture of leaf trapping dust particles in its fibres (scale bar is 200 mm).

154 Sample Preparation and Decomposition

(wetting agent, disper sant, solvent) to the wash might introduce unknown contam-

ination. Commercial soaps can have various c ontaminants that could enhance a

natural biogeochemical signature.

Tests conducted on combined stems and leaves of big sagebrush and on pine bark

involved analysis of washed and unwashed portion s of the same sampl e (Dunn et al.,

1993a). The sample site was near the Nickel Plate gold skarn open pit mining op-

eration in southern British Columbia. The high Au and As concentrations are a

reflection of this mineralization (Table 6-II). Washing was extremely rigorous in that

portions to be washed were placed in deionized water in an ultrasonic bath for 1 h.

After drying, the samples were reduced to ash by controlled ignition at 475 1 C and

concentrations were determined by INAA. Results of the 35-element analysis showed

loss of Fe from the woody tissues (twigs and bark), but the only element to exhibit an

appreciable and consistent difference was K. Values for all other elements fell within

the narrow range of analytical precision typically obtained by INAA.

In a test that involved some extremely dusty outer bark of Ponderosa pine (Pinus

ponderosa), unwashed and washed samples wer e analysed as well as the dust that

settled out from the distilled water used for the washing. Samples were put in a

beaker containing deinonized water that was placed on an ultrasonic shaker for

30 min. The results (Table 6-III) showed that concentrations of most of the trace

elements were higher after washing, suggesting that adhering dust (mos tly silicates)

diluted the trace element composition of the bark. This was confirmed from exam-

ination of the analysis of the dust removed by the washing. Elements yielding lower

concentrations after washing were the major nutrients P and K, and traces of Mo.

A study of very dusty samples from the Ballarat East goldfield of Victoria, Aus-

tralia, found that washing failed to remove the contaminants. It was con cluded that

TABLE 6-II

Effects of thorough washing in distilled water (1 h in ultrasonic bath) on the chemical com-

position of different plant tissues. Concentrations in ash determined by INAA

Sagebrush twig Sagebrush leaf Lodgepole pine bark

Unwashed Washed Unwashed Washed Unwashed Washed

Au (ppb) 270 294 279 267 293 298

As (ppm) 100 95 50 64 150 160

Ba (ppm) 330 300 140 150 590 590

Co (ppm) 4 4 2 2 11 10

Fe (ppm) 6300 5500 2500 2800 17,600 17,200

K (%) 26.3 24.3 17.4 13.2 3.2 1.5

Mo (ppm) 11 10 9 11 2 3

Sb (ppm) 1.7 1.5 0.7 1.1 4.2 4.3

Zn (ppm) 570 550 530 610 1300 1400

155Biogeochemistry in Mineral Exploration

the rough outer bark of some Eucalyptus species should be avoided in areas of

potential dust generation (Arne et al., 1999).

Thanks to developments in ICP-MS that now permit determinations of ultra-

trace levels of a broad range of elements in dry tissues, further insight and quan-

tification of the elements that are removed during washing can now be more readily

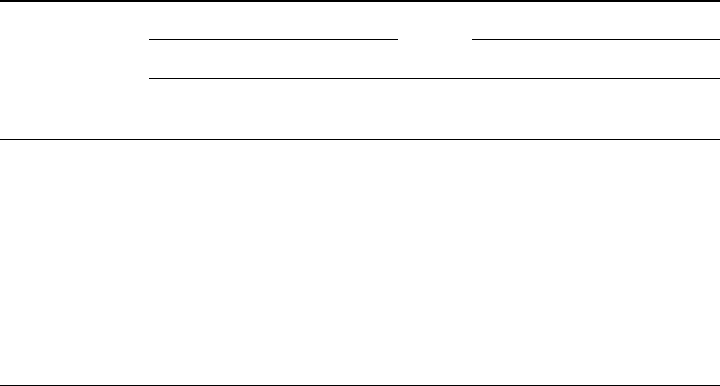

obtained than was previously practical. Figure 6-3 shows results of tests on dry leaves

(with a felted texture, not unlike that of sagebrush) and stems from a genus of the

persimmon family (Diospyros spp.) from Africa. Washed samples are shown as dia-

monds and unwashed samples as open triangles. Analyses of stems are shown on the

left half of each chart, followed by plots for the leaves from these stems. On the far

right of each chart the average values of washed versus unwashed are shown, and for

most elements these are almost identical.

Figure 6-3 shows that patterns of washed versus unwashed samples are similar for

Cd, Fe, Ti and Mo, and concentrations are mostly within the usual levels for an-

alytical precision for these elements at the concentrations present (see Chapter 8). In

the plot of Zn, the profile for the twigs indicates that washing may have remove d

particulates that were slightly diluting the Zn signature, because the unwashed twig

samples yielded marginally lower concentrations than their washed counterparts;

however, this difference is not apparent for the leaves. Conversely, the last plot sho ws

that washing removed some of the K from the leaves. This finding is in accord with

the results of vigorous washing illustrated in Tables 6-II and 6-III.

TABLE 6-III

Analysis of Ponderosa pine bark: dusty (unwashed), washed and the derived dust. Samples

collected several kilometres from an open pit exposing copper and gold-rich mineralization

(Iron Mask batholith, near Kamloops, British Columbia). Washing was for 30 min in distilled

water on an ultrasonic shaker. Concentrations are in ash, determined by INAA (As, Au, Sb)

and ICP-ES for the remaining elements

Unwashed Washed Dust washed from the bark

Ash yield (%) 1.07 1.05 –

Cu (ppm) 3265 3642 291

Au (ppb) 67 140 19

As (ppm) 39 39 3.4

Sb (ppm) 4.4 5 0.5

Pb (ppm) 239 259 22

Zn (ppm) 1172 1328 44

Cd (ppm) 37 39 o1

Mo (ppm) 18 15 o1

P (%) 1.05 0.85 0.6

K (%) 3.31 2.46 0.06

156 Sample Preparation and Decomposition

Washed (diamonds) v unwashed (open triangles)

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

Cd ppm

Cd ppm

Twigs

Leaves

Averages

Washed (diamonds) v unwashed (open triangles)

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

0.12

0.14

0.16

Fe %

Fe %

Twigs

Leaves

Averages

Washed (diamonds) v unwashed (open triangles)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Ti ppm

Ti ppm

Twigs

Leaves

Averages

Washed (diamonds) v unwashed (open triangles)

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

Mo ppm

Mo ppm

Twigs

Leaves

Averages

Washed (diamonds) v unwashed (open triangles)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Zn ppm

Zn ppm

Twigs

Leaves

Averages

Washed (diamonds) v unwashed (open triangles)

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

K %

K %

Twigs

Leaves

Averages

Fig. 6-3. Comparison of element concentrations in washed versus unwashed twigs and leaves of Diospyros spp.

157Biogeochemistry in Mineral Exploration

Of the elements determined in the study of Diospyros, in both leaves and twigs

almost identical pa tterns were derived from the washed and unwashed portions for

Ag, Al, Bi, Ca, Cd, Co, Cs, Fe, Ga, K, Mg, Mo, Na, Ni, P, Pb, S, Sc, Se, Th, Ti, Tl,

U and V. Leaves generally had more consistent relationships between washed and

unwashed portions than did the twigs; additional elements with similar profiles from

the leaf tissues (washed and unwas hed) were Au, Ba, Cr, Cu, Mn and Zn. No element

yielded a washed versus unwashed profile of concentrations that was substantially

different. It is noteworthy that elements actively used in physiological processes (B,

K, Ca, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Mo, Na, P, S, Zn) were more homogenously distributed

between the leaves and twigs than the non-essential elements that constitute the

remainder of the list, e.g., Ag, Al, As, Bi, etc., of which some were higher in twigs,

and some higher in leaves.

A study of vegetation samples from close to the Giant gold mine near Yellowknife

(NWT, Canada) and from a site some 1.5 km distant served to determine differences

in anthropogenic and natural sources (Dunn et al., 2002) and the effects of washing

samples. Among the concluding remarks the following was noted.

The environment of the sample sites is atypical of the boreal forest in general, in that the

vegetation samples were collected from close to a significant source of metals derived from

the Giant mine and mill. A measure of the amount of particulates adhering to the plant

surfaces can be obtained from determining the ash yield of unwashed and washed samples,

but washing does not remove all of the particulate material because some is contained

[entrapped] within the plant structure (particularly in the bark). Thus, in this environment,

washing does not give an accurate estimate of the element uptake purely from natural

sources, and an anthropogenic component is dominant in all of the samples tested. Some

of the anthropogenic component falls to the ground and is subsequently dissolved in

groundwater and taken up by the plant roots then sequestered in the tree and shrub tissues.

To summarize the many options described above, for exploration purposes the

addition to the sampling/preparation/analytical process of the extra step of washing

creates another possible source of error. During sampling and preparation there are

several potent potential sources of error that include sample identification, cross-

contamination and external contamination. Each can contribute to masking the

natural biogeochemical signature. If a sample drops to the ground during sampling,

another sample should be collected. If samples are obviously dusty, they should be

rinsed in running water. However, in most situations, sample washing is not a re-

quirement. The spatial patterns derived from unwashed samples are typically robust

and are likely to be similar to, if not exactly the same as, those derived from washed

samples. Potentially, because of the high solubility of some elements, a relev ant

subtle biogeochemical signature could be washed away by vigorous washing. A re-

curring theme in this book is to remember to ask ‘are the data fit for the purpose?’ In

general, a small amount of background dust contamination (but not from a highly

enriched source such as a smelter) can be tolerated without compromising the in-

tegrity of a survey.

158

Sample Preparation and Decomposition

PARTICLE AND SAMPLE SIZE

If the selected analytical protocol is to digest dry samples completely in acids, it

should not make any difference whether they are coarsely ground or milled to a fine

powder. Usually, each commercial laboratory applies standard acid concentrations

and digest durations in preparing samples for rapid instrumen tal multi-element

analysis. As a result, if samples are coarsely ground, there may be some particulate

residue that does not go completely into solution in the prescribed time. Certainly,

the finer the powder the more readily a sample will go into solut ion.

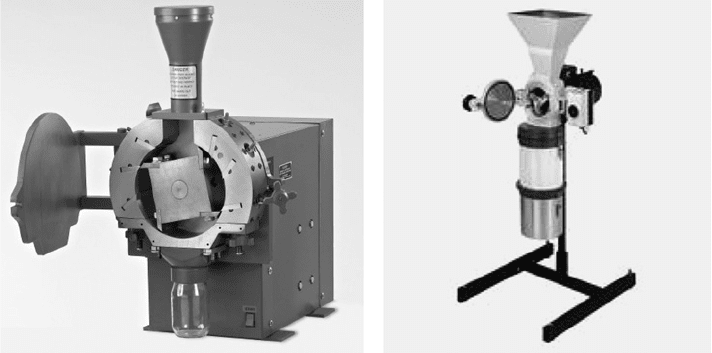

Simple coffee-mill types of equipment with rotary blades are adequate for re-

ducing soft to moderately hard tissues to a fine powder. However, cones, twigs

greater than 5 mm in diameter, and twigs of hard woods such as Acacia are difficult

to grind in anything other than a Wiley or Retsch-type of mill that has a shearing

action (Fig. 6-4).

In the latter mills, adjustable hard tool steel knives are bolted to a removable

rotor. These knives work against stationary knives, independentl y adjustable, that

are bolted into a steel frame. The sheared particles pass through a hardened steel

mesh to ensure consistent particle size. Typically, a mesh with 1 mm apertures is used,

although optional sizes range from 0.5 to 6 mm. It takes considerably longer for

material to pass through the fine-aperture mesh screens, thereby increasing sample

preparation costs. If very fine particles are required, samples can be passed through a

mill that grinds by high-speed rolling of the sample against an inner durable grinding

surface and then passes it through a fine mesh screen. These grinding mills are rapid

and effective, but for multi-element exploration purposes the user must be aware of

potential contamination from the grinding surface, because it is usually tungsten

Fig. 6-4. Left: Model 4 Wiley mill (available from Thomas Scientific); right: Model SM 100

mill (available from Retsch

TM

GmbH).

159Biogeochemistry in Mineral Exploration

carbide that has a cobalt-bearing binding agent. Table 6-IV compares elements for

which analyses of samples milled in a shear-type of mill were significantly different

from those passed through a tungsten carbide-bearing rotary-plate grinding mill.

Data for all other elements determined (53) were comparable.

The scientific literature offers several suggestions with regard to the optimum

particle size to which vegetation tissues should be milled. Vien and Fry (1988) rec-

ommend milling to a median size less than 20 mm, whereas Carrion et al. (1988)

determined that for pine needles the fraction between 106 and 160 mm is preferable

for obtaining optimum analytical precision.

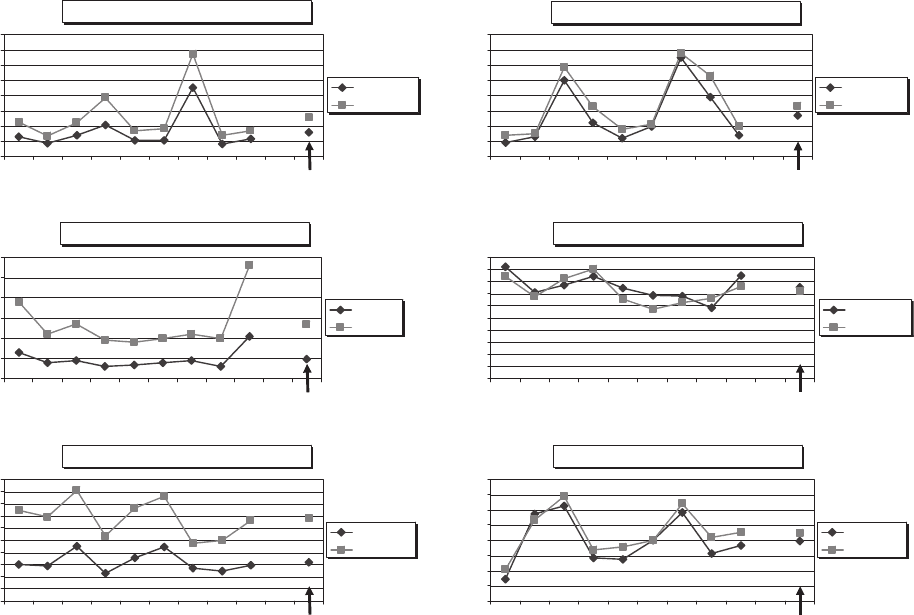

Figure 6-5 shows results of some Douglas-fir outer bark that was coarsely ground

(particle sizes of less than approximately 3 mm) compared to the same material that

was ground to a fine powder (o0.5 mm). There is a very good correlation between the

datasets obtained for each element; for some elements the concentrations were the

same (within the limits of analytical precision), but the finer grinding commonly

released slightly higher levels of elements. The amount of Fe and Hg released was

appreciably higher in the finely ground fraction. This indicates that particle size can be

important, and for exploration purposes the key to obtaining meaningful results rests

with being consistent in the particle sizes of milled samples. Of lesser importance is the

desirability of selecting a particle size that provides the highest concentrations, be-

cause the underlying tenet for exploration is that the primary objective is to establish

contrasting spatial relationships among carefully acquired biogeochemical data.

TABLE 6-IV

Elements exhibiting different concentrations from passing two separate wood samples through

a shear-type mill compared to a rotary disc-type of mill

Sample 1 Sample 2

Very fine Fine Ver y fine Fine

Disc

grinder

Shear

mill

Disc

grinder

Shear

mill

Bi (ppm)

0.25 0.05 0.11 0.02

Ce (ppm)

0.05 0.01 0.03 0.01

Co (ppm)

0.06 0.04 0.03 0.02

Cu (ppm)

1.33 0.73 1.68 1

Fe (%)

0.006 0.001 0.005 0.001

Ni (ppm)

20.3 0.1 10.5 0.7

Pb (ppm)

0.6 0.2 0.51 0.2

W (ppm)

12.9 0.1 6.7 0.5

Y (ppm)

0.006 0.001 0.004 0.001

Zr (ppm)

0.08 0.03 0.06 0.02

160

Sample Preparation and Decomposition

Douglas-fir: coarsely (C) v. finely(F) milled bark

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

Conc.

Ba_C ppm

Ba_F ppm

Douglas-fir: coarsely (C) v. finely(F) milled bark

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

Conc.

Cd_C ppm

Cd_F ppm

Douglas-fir: coarsely (C) v. finely(F) milled bark

0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

0.06

12 3 4

567891011

Sequence #

Conc.

Fe_C %

Fe_F %

Averages

1234

567891011

Sequence #

Averages

12 3 4

567891011

Sequence #

Averages

1234

567891011

Sequence #

Averages

12 3 4

567891011

Se

q

uence #

Averages

1234

567891011

Se

q

uence #

Averages

Douglas-fir: coarsely (C) v. finely(F) milled bark

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Conc.

Cu_C ppm

Cu_F ppm

Douglas-fir: coarsely (C) v. finely(F) milled bark

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

Conc.

Hg_C ppb

Hg_F ppb

Douglas-fir: coarsely (C) v. finely(F) milled bark

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Conc.

Sr_C ppm

Sr_F ppm

Fig. 6-5 . Douglas-fir bark: analysis of coarsely milled material compared to finely ground. One-gram samples digested in HNO

3

then aqua

regia with ICP-MS finish.

161Biogeochemistry in Mineral Exploration