Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

were injured. Seven sailors a nd a policem an were also injured (Tuttle 1970, 23).

On June 16, a white mob rampaged through through the black neighborhoods in

Longview, Texas, after reports circulated that a black male ha d been discovered

in a white woman’s bedroom. Tensions between the white and black communities

had been ratcheted up by black efforts to organize cooperative sto res to compete

with local white merchants and by attempts by black farmers to circumvent local

white brokers by selling their produce to directly to buyers in Galveston.

The thir d major race riot of 1919 broke out in Washington, D.C., amid l urid

rumors fanned by the local press that b lack rapists had been assaulting white

women. These inflammatory reports (which were unsubstantiated) generated

widespread anger among whites, particularly white servicemen stationed near

the Capitol. On July 20, Washington erupted. Bands of soldiers, sailors, and

marines roamed through th e city att acking any black they encountered. When

the Washington police proved unable or unwilling to control the rioters, Secretary

of War Newton D. Baker ordered 2,000 regular troops into the city. Their presence,

combined with the arrival of a weather front that generated showers and thunder-

storms on July 22, brought the violence to a halt. The riot left six dead and more

than 100 injured (Tuttle 1970, 30).

The May and June disorders paled, however, in comparison to the Chicago riot

of late July. Racial tensi ons in Chicago had been high for decades bef ore the war.

White gangs, who referred to themselves as “athletic clubs,” consisted of young

men in their teens and early 20s and spent years terrorizing blacks. Many of them,

nearly as poor as their targets, were of Irish descent. The Chicago police, many of

whose members came from the same neighborhoods and the same social and ethnic

background, sympathized w ith the “athletic clubs” and did little to restrain them.

They were intensely territorial going so far as to claim stretches of Lake Michigan

beachfront as their own. These discontented whites were augmented in 1919 by

returning white servicemen and unemployed workers who blamed blacks for the

shortage of jobs. Throughout the spring and early summer, they had been anticipat-

ing a riot. Indeed, many soug ht to instigate one themsel ves. Blacks, on their part,

felt mounting anger over white violence toward their community. Many, including

a number of discharged soldiers, armed themselves to defend their neighborhoods.

The precipitating incident took place on Sunday afternoon, July 27, on a South

Side beach when four young black men on a raft on the lake inadvertently floated

into white territory. At around the same time, five young blacks on the beach

strolled close to the white boundary, t riggering a barrage of curses, stones, and

bricks. Blacks, in t urn retaliated. T he arrival of the police only added fuel to the

fire. They arrested several blacks but no whites, furthe r angering other African

Americans. Shots were fired, killing one white policeman and a black man. The

race war that so many had feared or anticipated had begun.

768 Red Summer (1919)

By the next morning, white gangs were roaming through black neighborhoods

near the Chicago Stockyards. In this area where blacks and whites worked together

and lived in close proximity to one another, there was a constant potential for vio-

lence. Streetcar transit points were particularly dangerous. Gangs of whites

dragged blacks off the streetcars and beat them savagely.

The patterns established on July 27 and 28 repeated themselves at a steadily

declining rate over the next week. Whites invaded blac k areas, indiscrimi nately

shooting at and beating any blacks they saw. Blacks often used violence in self-

defense, but these instances only inflamed whites. Rain and the arrival of Illinois

National Guardsmen combined to slow down the rioters and by August 1, the riot-

ing had ceased. Over five days, 38 men had died (23 black and 15 white) and

537 men, women, and children (342 of whom were black) had been injured

(Hagedorn 2007, 316). Hundreds of homes and businesses, m ost of them owned

by blacks, had been burned or vandalized.

What made the Chicago riot unique, apart from the scale of the destruction and

the number of deaths, was that it was the first to have occurred in a large northern

industrial city. In addition, Chicago was different because of the organized nature

of the violence . Organized whi te gangs of hoodlu ms had targeted specific black

neighborhoods, and black resistance was far more extensive and o rganized than

in any other riot. The Chicago riot came closest of all the urban riots of that

summer to a pitched racial battle.

Most of the outbreaks following the Chicago riot were not as organized or

destructive but had fundamentally the same cause—postwar economic disloca-

tions that fed tensions between blacks and whites. The most serious of these

northern outbreaks occurred in Omaha, Nebraska, in September, when a mob

lynched a black man accused of rap ing a white woman. When the mayor and the

police tried to intervene to stop it, the mob turned on them and burned the city jail

to the ground. Federal troops from Iowa, Kansas, and North Dakota finally quelled

the violence.

The worst of the Red Summer racial incidents did not occur in the North, but in

the vicinity of Elaine, Arkansas, when armed bands of whites engaged in a whole-

sale massacre of blacks. It made clear how far southern whites and their leadership

were willing to go to maintain white supremacy and how dangerous it was for

blacks to organize to assert their rights. White anger and anxiety in the Mississippi

Delta region had been growing all spring and summer because of the black exodus

to the North over the previous two years. Reports of racial and labor viole nce in

the North contributed to their concern. They were all too willing to believe reports

of the involvement of pro-Bolshevik and radical agitators in these disorders.

The return of large numbers of black soldiers from overseas was a focal point of

white anxiety. There were rumors that French women were writing love letters to

Red Summer (1919) 769

blacks urging them to demand equality. These lurid reports also fed white fears

that blacks were planning an insurrection aimed a t massacring whites. African

American soldiers wearing their uniforms were fr equently targets of harassment,

threats, and beatings.

Particularly alarming for the leaders of the white economic and political estab-

lishment were reports that black sharecroppers, frustrated over not getting a fair

price for their cotton, were organizing a union t o bargain for a larger p ercentage

of the cotton revenue. These organizing efforts became the flash point from which

the violence in the Arkansas Delta grew. On September 30, black sharecroppers

met in a church near Hoop Spur, Arkansas, near Elaine, to discuss the possibilities

of seeking legal assistance to sue white landowners, merchants, and mill owners to

gain a larger share of the profits from the cotton crop. A group of whites arrived at

the church and tried to break up the meeting. In the resulting altercation, shots

were fired and one white was killed.

The white reaction was one of unprecedented savagery as whites at virtually

every social level in eastern Arkansas panicked at the prospect of a black con-

spiracy to commit mass murd er. Over the e nsuing week, whites , including many

trucked in from Mississippi, Louisiana, and Tennessee and federal troops sent from

Fort Pike, killed anywhere f rom 100 to 800 blacks; five whites died (Hagedorn

2007, 379; Whitaker 2008, 327–329). Even after the killing subsided, hundreds of

blacks remained in hiding.

Incredibly, not a single white was ever prosecuted or even investigated in con-

nection for the Elaine Massacre. Walter White of the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) investigated the massacre at great

personal risk and identified a number of whites who were involved, but his report

was received with derision and anger by whites in Arkansas. White authorities in

Elaine engaged in mass arrests of blacks and brought 73 of them to trial in Novem-

ber 1919. Of these, 12 were sentenced to death for conspiring to instigate an upris-

ing and for murder. The others were sentenced to life imprisonment (Whitaker

2008, 180–184).

The result of the Elaine inciden t reflected a pattern in the response to the vio-

lence of the summer of 1919. In seeking to explain the causes for the Red Summer

riots, the authorities initially examined those black persons involved. If blacks had

resisted, white investigators associated them with radical agitators sympathetic to

the Russian Bolsheviks. This was the case in the established authorities’ reaction

in Elaine and in other disorders in the South. If blacks had not fought back or

had been overw helmed, authorities blamed labor agitators or foreign Communist

agents. Most of the investigations were not thorough and were colored by the prej-

udices and social outlook of the local authorities. Most law enforcement offici als

viewed increased repression of blacks as the answer for preventing more violence,

770 Red Summer (1919)

and the violence of 1919 led to calls for more money to hire more police. An

exception to this pattern was the investigation of the Chicago riot by the Chicago

Commission on Race Relations, which used tools developed b y the sociology

department at the University of Chicago to provide analyses of the conditions that

had caused the outbreak.

The violence of the summer of 1919 gradually abated. Although sporadic riot-

ing occurred durin g the interwar period (particularly the Tulsa Riot of 1921),

there were no further widespread disorders until the 1960s. The conspiracy theo-

ries surrounding the disorde rs at the time were never proven, and the prevailing

analysis is that a climat e of economic disloca tion and social unrest caused the

violence.

The most important consequence of the Red Summer of 1919 was the galvanizing

of the civil rights movement. One of the earliest legal victories for the NAACP

grew out of the Elaine, Arkansas, tragedy , when the Supreme Court in Moore v. Dempsey

overtu rned the con victions of all 73 black defendants in the Elaine case because of how

their trials had been conducted. The result was an extension of the authority

of the federal courts to oversee the states’ treatment of defendants’ rights and the

application of the due process clause as a regulator of state criminal procedures.

Although the civil rights revolution did not come to full fruition until the 1950s

and 1960s, the viole nce of the World War I era strengthened the arguments of

groups such as the NAACP and their white liberal allies and of individuals such

as Ida B. Wells and W. E. B. Du Bois for legislation to protect blacks and other

minorities and furthering the education of Americans of the need to ensure black

social, economic, and political equality. It would take 40 years, but the seeds of

the 1960s civil rights revolution were planted in the mob violence of 1919.

—Walter F. Bell

See also all entries under Stono Rebellion (1739); New York Slave Insurrection (1741);

Antebellum Supp ressed Slave Revolts (1800s–1850s); Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831 );

New Orleans Riot (1866); New Orleans Race Riot (1900); Atlanta Race Riot (1906);

Springfield Race Riot (1908); Houston Riot (1917); Tulsa Race Riot (1921); Civil Rights

Movement (1953–1968); Watts Riot (1965); Detroit Riots (1967); Los Angeles

Uprising (19 92).

Further Reading

Barnes, H arper. Never Been a Time: The 1917 Race Riot that Sparked the Civil Rights

Movement. New York: Walker & Company, 2008.

Hagedorn, Ann. Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919. New York: Simo n and

Schuster, 2007.

Marks, Carole. “Black Workers and the Great Migration North.” Phylon 46 , no . 2 (2nd

Quarter, 1985): 148–161.

Red Summer (1919) 771

Tuttle, William M., Jr. Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919. Urbana: University

of Illinois Press, 1970.

Voogd, Jan . “Red Summer of 1919.” In Conspiracy Theories in American History:

An Encyclopedia , ed. Peter Knight. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2004. History

Reference Online at http://www.historyreferenceonline.abc-clio.com.

Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of the Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for

Justice That Remade a Nation. New York: Crown Publishers, 2008.

772 Red Summer (1919)

Great Migration

The phrase Great Migration refers to the movement of African Ame ricans from

the rural areas of the southern United States to t he industrial cities of the N orth,

Midwest, and West from 1910 to 1960. Some scholars divide the Great Migration

into two phases—the Fir st Great Migration (1910–1930) and the Second Gre at

Migration (1940–1970)—but both followed similar patterns. The sources of the

movement were the desire among blacks for more freedom from the oppressive

conditions they faced in the Jim Crow South as well as economic opportunities

in norther n cities. In addition, they found themselves be ing pushed out of their

homes in the South by economic and environmental changes.

African Americans had been moving to cities—both southern industrial centers

such as Atlanta, Georgia; Birmingham, Alabama; Wilmington, North Carolina; and

Norfolk, Virginia; and northern industrial centers—since the Civil War. The migra-

tion north accelerated in the 1880s and 1890s as southern states enacted laws that vir-

tually stripped blacks of the rights they had gained during Reconstruction and

unleash ed a wave of violence and intimidation against blacks aimed at enforcing

white supremacy. Nevertheless, in 1910, over 60 percent of the black population in

the United States was employed in southern agriculture, mostly as sharecroppers on

large cotton farms, and 18 percent worked as domestic servants (Marks 1985, 150).

The steady movement of Afr ican America ns to the North accelerated with the

outbreak of war in Europe. The onset of World War I shut off the flow of immigra-

tion, thus denying northern industries a pool of cheap immigrant labor they could

draw on to maintain a labor market surplus. At the same time, war orders from the

European belligerents and Preside nt Woodrow Wilson’s 1916 preparedness cam-

paign stimulated higher demand for labor. In this context, northern industry turned

to black labor. To an extent unknown before the war, industrial employers began to

experiment with hiring blacks into positions that had previously been closed to them.

At the same time, conditions in the South served to push many blacks into leav-

ing the South. A series of severe floods in 1916 forced thousands of sharecroppers

from their farms. Disenfranchis ement, segregation, and the cont inui ng threat of

violence—particularly an increase in the frequency of lynchings—also worked

as inducements for blacks to leave. The biggest consideration, however, was

wages. Migrants moving north could easily make more money, even as unskilled

laborers, than they could in any occupation in the South. On average, hourly pay

in the South was only three-quarters of those in the North (Marks 1985, 152).

Whatever their reasons for leaving, between 1915 and 1920, an estimated

400,000 African Americans left the South for northern cities (Barnes 2008, 65).

They concentrated in Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Columbus, Ohio,

773

in the Midwest and New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh in the East. The influx

of black migrants into northern cities put a strain on housing and city services.

The greatest strain, however, was on race relations between the burgeoning

black communities and working-class ethnic whites w ith whom they competed

for jobs. White fears of black competition exploded into violence t hat became

more common in 1919 as large numbers of returning black and white servicemen

put even more pressure on the depressed. These tensions culminated in the

Chicago riot of July 1919.

The Great Migration continued in the 1920s driven by increased mechanization

of southern agriculture and continuing violence and oppression in the Jim Crow

South. Although it slowed during the Depression decade of the 1930s, the Migra-

tion surged again during and after World War II, permanently altering the political,

social, and demographic landscape in the United States.

—Walter F. Bell

774 Red Summer (1919)

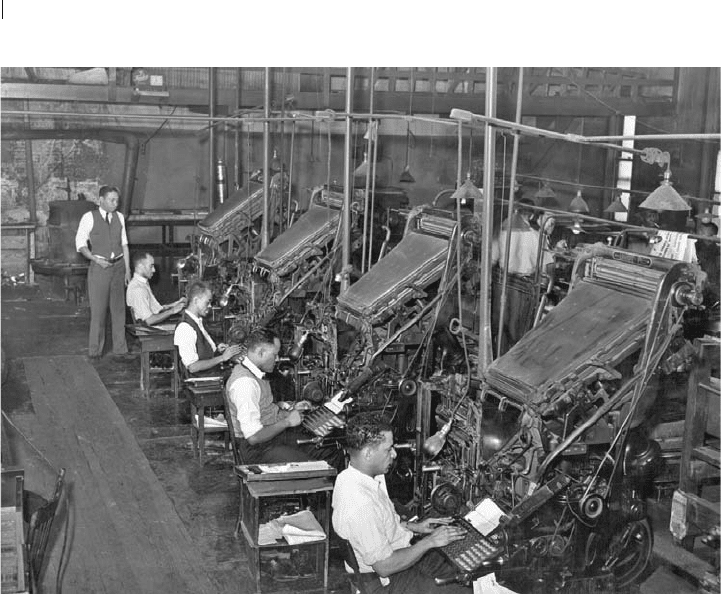

Typesetters work at their keyboards at the Chicago Defender, an African American

newspaper founded in Chicago in 1905. The Defender was the most influential African

American newspaper in the United States during the early and mid-20th century and

played a major role in the migration of African Americans from the South to the North.

(Library of Congress)

Further Reading

Barnes, H arper. Never Been a Time: The 1917 Race Riot that Sparked the Civil Rights

Movement. New York: Walker & Company, 2008.

Marks, Carole. “Black Workers and the Great Migration North.” Phylon 46 , no . 2 (2nd

Quarter 1985): 148–161.

Trotter, Joe William, Jr., ed. The Great Migration in Historical Perspective: New Dimen-

sions of Race, Class, and Gender. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Lynching

Lynching is the killing of individuals by mobs acting outside the law. It was

common in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Lynching

often occurred on the western frontier or in newly settled areas, where social conflict

prevailed and where legal resources were remote or distrusted by members of the

community. It became widely associated with the enforcement of white supremacy

in the southern United States after the American Civil War when the Ku Klux Klan

and other white terrorist organizations, used lynching and other forms of violence to

keep African Americans from voting or organizing against the white power struc-

ture. Lynching, however, was not confined to the South, nor was it always racially

motivated. It usually occurred during times of change and social unrest.

The Progressive Era and World War I was an unsettled period of social conflict. As

such, the conditions were conducive for frequent lynching incidents. During the years

of American belligerency against Germany (1917–1918), the number of lynching

incidents shot up as the stresses of wartime change aggravated social and racial divi-

sions. These tensions were further inflamed by anti-radical hysteria growing out of

the Russian Revolution and wartime anti-German and anti-ethnic feeling. Mobs fre-

quently harassed and often killed German American citizens and their sympathizers.

Vigilantes in the western states regularly attacked striking workers and labor organiz-

ers, especially those affiliated with the International Workers of the World (IWW).

Mob violence and lynchings in the wartime and early postwar periods occurred

most frequen tly, however, in the South and were connected with the maintenance

of white supremacy and the social and economic status quo. Tensions revolved

around African Americans attempting either to organize themselves to demand

economic justice and political equality or to leave the oppressive conditions in

the rural South and migrate north to take jobs in wartime industries. White southern

planters and mill owners, seeking to maintain a cheap and docile workforce , were

infuria ted by northern newsp apers t hat advertised the availability more jobs and

economic freedom outside the South. In 1917, 44 blacks had been lynched, mostly

in southern locations. In 1918, 64 more had died (Hagedorn 2007, 13).

Red Summer (1919) 775

The incidence of lynching shot up after the Armistice of November 1918.

Between November 1918 and June 1919, there were 28 reported lynchings. Nearly

half of these incidents involved allegations of sexual assault by black men against

white women. Discharged African American soldiers were a frequent target because

of fears that they would use their record of service in the war to demand equality.

The reaction of the federal government to this mob violence was mixed. The

Wilson administration was indifferent to lynching as was most of the American

public. Despite appeals from prominent blacks and longtime agitation from promi-

nent northern Progressives f or federal antilynching l egislation, Wilson took no

action. In the face of growing racial violence in the South, many blacks fled to

northern cities, particularly Chicago, where the influx of so many poor migrants

fed racial tensions that contributed to racial violence in the North.

The rash of lynchings and other attacks on African Americans that were part of

the violence of 1919 pointed up the lack of legal protections for racial minorities

and polit ical dissenters in the United States. In the years after World War I, these

incidents gave ammunition to supporters of federal antilynching laws—individuals

such as Ida Bell Wells-Barnett, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Robert Wagner and organiza-

tions such as the National Association f or the Advancement of Colored People.

Calls for legal equality and passage of antilynching laws intensified. Lynching vir-

tually ended in the West, Midwest, and Northeast, but the practice continued in the

South, although at a steadily declining rate, until after World War II.

—Walter F. Bell

776 Red Summer (1919)

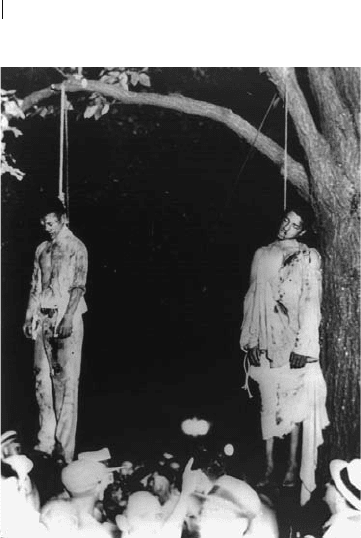

Two African American men, the victims of

a lynching, hang from the limbs of a tree

in Marion, Indiana, in 1930. (Library of

Congress)

Further Reading

Hagedorn, Ann. Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919. New York: Simon &

Schuster, 2007.

Pfeifer, Michael J. Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874–1947. Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Race Riots

Race riots are communal disorders in which mobs, incited by resentment or fear of

another racial or ethnic group they view as alien or threatening, carry out violent

acts against property, institutions, or individuals associated with that g roup. In

the United States, race riots were a frequent occurrence in the late 19th and early

20th centuries. Most often the targets were African A merican neighborhoods in

industrial cities wher e racial tensions were high because of the influx of large

numbers of blacks and the competition between them and working-class white s

for housing and jobs. They happened with growing frequency in the years during

and immediately following World War I, a time of intense racial and class conflict.

In almost every instance, whites were the aggressors.

Riots generated by racial and ethnic conflicts were hardly new. Bloody and

des tructive race riots targeting blacks occurred before th e Civil War in Philadel-

phia (1834) and Cincinnati (1841).The Draft Riot that took place in New York

City in July 1863 at the height of the Civil War resulted from resentment of poor

whites, particularly Irish immigrants, against conscription into the Union Army

and w hat they perceived as preferential treatment of blacks. The rioters killed

more than 100 black men, women, and children.

The seeds of the racial violence of the Progressive Era were sown as many

blacks, frustrated over the growing racialoppressionbywhitesintheSouthin

the 1890s, left the rural South for what they hoped was more freedom and a better

life. They concentrated in Chicago, St. Louis, and smaller industrial centers in the

Midwest and upper South. They encountered conflicts between large corporations

and white ethnic immigrant workers seeking to organize into unions and bargain

collectively for better wages and working conditions. In the depressed economic

conditions of the 1890s and early 1900s, corrupt local politicians and business

leaders played blacks and whites off ag ainst each other. Poverty a nd economic

insecurity among lower-class whites who were unemployed and desperate bred

intense anger and resentment. White racist politicians—abetted by propaganda

that often focused on allegations of black sexual assaults on white women—made

sure that anger was directed downward against blacks rather than against the

political and economic establishment.

Red Summer (1919) 777