Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Starting in July, however, groups of Mexican-American ranchers in South Texas

launched a series of raids targeting prominent landholders, irrigation works, and

railroad infras tructure. By October, they had succeeded in mounting scores of

raids (sometimes striking multiple targets on the same day), killing several promi-

nent A nglo farmers known locally for mistreatin g their hired hands, and pressur-

ing hundreds of Anglo ranchers to move out of the countryside to the relative

safety of towns and cities, all while avoiding pitched battles with the federal sol-

diers who so badly outnumbered them. As many as 80 men participated in the larg-

est attacks, sometimes clearly adhering to a military-style command structure that

differentiated between officers and soldiers. The leaders of the uprising claimed at

various points to be implementing the plan, and issued an altered version of it

stressing the grievances of local Mexicans and Mexican Americans, but their

precise connection to the manifesto remains unclear.

Local conditions created the impetus behind the uprising. A decade before, a

railroad connection prompted the influx of thousands of Anglo farmers into what

had remained a majority-Hispanic area since its conquest by the United States in

the 1846–1848 war with Mexico. Economic pressure, violence, and fraud

deprived many Hispanic ranchers of their land, and racially exclusionary per-

sonal a nd political conduct by newcomer Anglos further inflamed tensions.

These dispossessed and threatened ranchers constituted the uprising’s base of

support, as many U.S. authorities at the time recognized. “[I]t is undoubtedly

true that majority of bandits operating in Cameron, Hidalgo, Starr, and Willacy

counties are residents of the United States,” concluded General Frederick Fun-

ston in August. The raiders also relied on their neigh bors for shelter, food, and

water as they misled their pursuers. “The population of the county is more than

95 percent Mexican birth and a very large proportion of this element is in sym-

pathy with the raiders or bandits, now apparently trying to get together,” wrote a

frustrated army commander in Rio Grande City at the height of the raids. “This

makes it most difficult to get information. I am endeavoring to work in harmony

with civil authorities but these are active only in protection of towns” (Johnson

2003, 96).

The Mexican Revolution, which had toppled the hemisphere’s oldest regime

and begun redistributing land to the dispossessed, had inspired many of those

who joined the rebellion, especially ranc her Aniceto Pizan

˜

a, who had long read

and distributed the publications of the Partido Liberal Mexicano, a key instigator

of the Revolution. In at le ast a few cases, revolutionary par tisans dir ectly partici-

pated in raids in August and Sept embe r. Emil ian o Nafaratte, the command er of

the revolutionary faction in control of northeastern Mexico at the time, gave logis-

tical support and arms to the uprising. Although not traditionally a supporter of the

rights of those of Mexican descent in Texas, Nafarrate may have viewed the

728 Plan de San Diego (1915–1916)

rebellion as a useful vehicle to express widespread Mexican anger at the United

States for its military occupation of Vera Cruz the year before.

A response to the uprising was not long in coming. The state government dis-

patched several companies of Texas Rangers (see the entry “Texas Rangers”) with

permission to enlist “Sp ecial Rangers” to suppress the revolt. The federal

government bolstered the presence of the army, soon calling up reserve units from

as far away as New York. The first vigilante executions took place less than three

weeks after the initial flurry of raids, as sheriff ’s deputies shot the brothers

Lorenzo and Gorgonio Manrı

´

quez in Mercedes, Texas. The justification—resisting

arrest by attempting to flee—became a common refrain as local law enforcement

authorities, private citizens, and Texas Rangers initiated a campaign of terror

aga inst anybody suspected of involvement with the raids, no matter how sle nder

the evidence. Local papers openly supported this campaign, as in the Lyford Cou-

rant’s declaration that “Lynch law is never a pleasant thing to contemplate, but it is

not to be denied that it is sometimes the only me ans of administ ering justice”

(Johnson 2003, 87).

The uprising itself continued to grow, its ranks bolstered by outrage at vigilan-

tism. (Aniceto Pizan

˜

a, who became one of the two princi pals of the revolt, along

with Luis de la Rosa, did not participate until his ranch was attacked and his

brother grievously i njured at the instigation of an Anglo neighbor who had long

coveted his land.) On August 8, Luis de la Rosa led about 60 men in an assault

on the headquarters of one of the divisions of the King Ranch, one of the largest

and most politically connected landholdings in the state. The rebels continued

their atta cks on rai lroads and other infra st ructure, burning four b ridges within a

20-mile radius of Browsnville and cutting telegrap h line connections to ma ny

of the region’s small towns. Still undaunted by the increasing number of U.S. soldiers

that they faced or by the transfer of Nafaratte away from the border, on October 19,

the rebels scored their most dramatic coup with the derailing of the morning train

some 12 miles north of Brownsville. With engine and front-most cars on their sides,

the assailants succeeded in killing sev eral soldiers and a prominent Brownsville offi-

cer , missing the district attorney and a former officer of the Te xas Rangers. Two days

later, a group of 60 to 80 accompanied with by a trumpeter playing battle songs fired

on a cavalry bunkhouse stationed near the border.

While most of the raids were aimed at Anglo targets, raiders also killed and har-

assed numerous Tejanos, especially deputy sheriffs and prominent landholders. In

other words, the uprising reflected not only racial divisions, but also economic ten-

sions. For example, Florencio Saenz, one of the few Tejanos to profit from the agri-

cultural boom of the early 20th century, was singled out for four attacks in August

and September by his Tejano neighbors, who succeeded in forcing him to close his

badly damaged store and abandon his productive fields for the better part of three

Plan de San Diego (1915–1916) 729

years. Some local Anglos w ere attuned to the pr edicament of more elite Tejanos.

As one observer put it, in the racial language of the time, “[t]here are a number of

well-known Mexicans who are law abiding and good citizens, whose condition is

worse at present than that of the Americans” (Johnson 2003, 85).

But what Tejanos might have to fear from one another soon paled in comparison

to what they had to fear from Anglos. Those suspected of joining or supporting the

raiders constituted the most obvious of targets, and so ethnic Mexicans w ere

lynched after nearly every major raid in 19 15. Unlike the U.S. Army, which

offered protection to Tejanos even as it pursued the raiders, the Texas Rangers

played a prominent role in many such occasions. The most notorious came after

the attack on the King Ranch, when several rangers posed with their lassos around

the corpse s of three men in a photo that soon circulated, like many depictions of

lynching across the country, as a postcard. Observers reported multiple incidents

of mass lynchings. In late September, for example, an army scout came across a

dozen or more bodies of men killed by Rangers near Ebenoza. The bodies

remained in the open for months. “I saw the bones about five or six months after-

wards, the skeletons,” recalled a local farmer. A prominent regional politician,

James Wells, remembered coming across the decomposing bodies aft er he saw

buzzards circling overhead and smelled something foul. Another description of

bodies “with empty beer bottles stuck in their mouths ...near Ebenezer” likely

referred to the same victims (Johnson 2003, 115).

Such killings became common by early fall, common enough to claim hun-

dreds, perhaps thousands o f lives. In mid-September, for example, a New York

reporter noted that “The bodies of three of the twenty or more Mexicans that were

locked up overnight in the small frame jail at San Benito were found lying beside

the road two miles east of the town thi s afternoon. All three of the men had been

shot in the back. Near Edinburg, where Octabiana Alema, a mai lcarrier, was shot

and beaten by bandits whom he came upon accidentally in the brush, the bodies

of two more Mexicans were found. They had been slain during the night. During

the morning the decapitated body of another Mexican roped to a large log floated

down the Rio Grande.” One Texas paper spoke of “a serious surplus population

that needs eliminating.” Prominent politicians proposed putting all those of Mexi-

can descent into “concentration camps”—and killing any who refused. “ There

have been lots who have evaporated in that country in the last 3 or 4 years,”

remembered one Anglo lawyer in early 1919 (Zamora 1919, 273–274).

The uprising itself was suppressed by the summer of 1916, after a long hiatus

from November to June. The flight of hundreds of Tej ano residents into M exico

in the fall of 1915, a stunning reversal of the large pattern of migration from

Mexico to the United States over the decade of the 1910s, may have deprived the

rebels of much of their base of support. The heavy deployment of federal soldiers

730 Plan de San Diego (1915–1916)

disrupted many of the raids, and revolutionary authorities in Mexico stopped sup-

porting them. In early June 1916, the rebels regrouped further north and mounted

several large raids to the south of Laredo. Smaller raids took place about 10 miles

west of Brownsville, and several U.S. Army units crossed into Mexico in pursuit.

The two nations were on t he brink of w ar: with U.S. forces already in north-

central Mexico chasing Pancho Villa after his March raid on Columbus, New

Mexico, b oth Mexican and American diplomats feared that an all-out U.S. inva-

sion was in the offing. Reports of the arrest of Luis de la Rosa began circulating,

and the bands of rebels did not reform or mount further attacks. In early July,

U.S. Army commanders stationed in south Texas reported that all was quiet. The

uprising never resumed.

The uprising and the orgy of racial violence tha t it unlea shed had l ong-term

reverbe ra tions . On the one hand, the years afte r the revolt saw the creation of a

racial caste system in south Texas, with Tejanos confronted by segregated schools,

public accommodations, and denial of political rights such as voting and jury ser-

vice in much of the region that had been one of the bastions of Mexican-American

power since its conquest in the U.S.-Mexico War some six decades before. On the

other hand, the crisis of 1915–1916 helped to convince key Tejano leaders in south

Texas of the futility of arme d resistance against Anglo dominance. In the 1920s,

key figures who had found themselves caught between the partisans of de la Rosa

and Pizan

˜

a on the one hand, and the Texas Rangers and vigilantes on the other,

played key roles in the founding of the League of United Latin American Citizens

(LULAC), the oldest surviving Mexican-American civil rights organization,

which devoted itself to agitating on behalf of the citizenship rights of Mexican

Americans by challenging segregation and disfranchisement.

The Plan of San Diego and the uprising tied to it never became a fixture of

widespread historical memory in the United States. Folk songs and family memo-

ries did circulate amongst the Tejano population. Local Anglo newspapers and his-

torical societies produced accounts and recollections of the uprising, but these

accounts’ emphasis on “banditry” divorced the uprising from its roots in Anglo-

Mexican relations and the economic development of south Texas. For decades,

professional historians paid the events little attention, in large part because of the

marginal role of the U.S.-Mexico border and Mexican American history within

the academy. But by the 1970s the increasing militancy of the Mexican American

population and the entry of numerous Mexican Americans into the ranks of profes-

sional historians helped to make the Plan of San Diego the subject of professional

historical inquiry. The first issue of Aztla

´

n, a pioneering journal founded in 1970s

to cover Mexican American history, containedananalysisofthemanifestoand

revolt, and since then two books dealing centrally with the uprising have been

published.

Plan de San Diego (1915–1916) 731

Translat ions of the original Plan of S an Diego may be found in the U. S. v.

Basilio Ramos Jr., et al., Criminal #2152, Southern District of Texas, RG 21, Fort

Worth Federal Records Center; in the “Gray-Lane Files,” Records of International

Conferences, Commissions, and Expositions. Records of the United States Com-

missioners of the American and Mexican Joint Commission, 1916, RG 43, United

States Nation Archives, Memo #11; in the Walter Prescott Webb Papers, Center

for Amer ican History, University of Texas at Austin, Box 2R290; and in General

Records of the Department of State, RG 59, M 274 (“Records of the Department

of State Relating to Internal Affairs of Mexico, 1910–1929, 812.00/23116”)

—Benjamin H. Johnson

See also all entries under Pueblo Revolt (1680); Pima Revolt (1751); Zoot Suit Riots (1942);

Day without an Immigrant (2006).

Further Reading

Go

´

mez-Quin

˜

ones, Juan. “Plan de San Diego Revisited.” Aztla

´

n 1 (Spring 1970): 124–130.

Johnson, Benjamin Heber. Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody

Suppression Turned Mexicans into Americans. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press,

2003.

Sandos, James. Rebellion in the Borderlands: Anarchism and the Plan of San Diego,

1904–1923. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

Texas State Legislature. Proceedings of the Joint Committee of the Senate and House i n

the Investig ation of the State Ranger Force. Austin: State of Texas, 1919.

Zamora, Emilio. The World of the Mexican Worker in Texas. College Station: Texas A&M

University Press, 1993.

732 Plan de San Diego (1915–1916)

Mexico

The United States and Mexico have experienced a fraught, sometimes explosive,

but inescapable relationship for nearly two centuries. Both nations were born in

anti-imperial revolts. Their early leadershadmuchincommon,viewingtheir

republics as harbingers of a more enlightened and progressive future. They both

faced parallel challenges in resolving the question of who would count as citizens,

in securing the loyalty of culturally and ethnically diverse populations, dealing

with independent Indian peoples, and in resolving the tensions between regional

and national governance.

The influx of American citizens and capital i nto the Mexican north in the

1820s and 1830s ended up in a war that re-drew the map of North America. In

1836, the Texas Revolution, launched by Anglo-American colonists and Tejanos

concerned with the centralizing tende ncies in Mexico, resulted in the formation

of the Republic of Texas, whose independence the Mexican government never

recognized. When the United States annexed Texas in 1845, some kind of conflict

between the two nations seemed inevitable. The following year, President James

Polk sent troops across the Nueces River, which Mexico claimed was the border,

and toward the Rio Grande, which the United States insisted was the proper

international line. Polk used the inevitable clash with Mexican forces as the justi-

fication for the massive invasion that eventually cost the weaker nation more than

half of its territory.

This defeat was followed by civil war in the United States. Protra cted conflict

over the standing of the Catholic Church and the powers of the central government

was intensified by a French intervention in the 1860s. Greater political stability

was secured in the long rule of Porfirio Dı

´

az (1877–1911), but at the cost, many

charged, of authoritarian rule and subordination to foreign (mostly American)

capital. In 1911, revolution broke out, forcing Dı

´

az out of office. But the rebel s

were divided amongst themselves, particularly over the question of the distribution

of the nation’s lands, which had been consolidated into fewer and fewer hands

during Dı

´

az’s regime. Moreover, elements of the old regime, particularly the

federal army, yearned for a return to power. So civil war wracked Mexico for the

rest of the decade, killing a tenth or more of its population, driving perhaps another

tenth of its population to flee to the United States, and prompting two military

occupations by the United States.

The Mexican Revolution had an enormous impact on the United States. The

arrival of hundreds of thousands of refugee s dramatically expanded ethnic

Mexican settlements, restoring their ties to Mexico and ult imately redrawing the

ethnic geography of the Southwest. The number of Mexican-descent people in

733

the United States tripled, at least, between 1910 and 1920. Some turmoil and con-

troversy accomp anied this process, as the episode of the Plan of San Diego indi-

cates. Mexican migration to the United States has been a constant since the

revolution, with the exception of the depression decade of the 1930s. Revolution-

aries defeated the representatives of Dı

´

az’s old regime and consolidated their rule

in the 1920s, in the process creating a much more unified nation with a strong

sense of national identity.

—Benjamin H. Johnson

Further Reading

DeLeo

´

n, Arnoldo. The Tejano Community, 1836–1900. Albuquerque: University of New

Mexico Press, 1982.

Montejano, David. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986. Austin:

University of Texas Press, 1987.

734 Plan de San Diego (1915–1916)

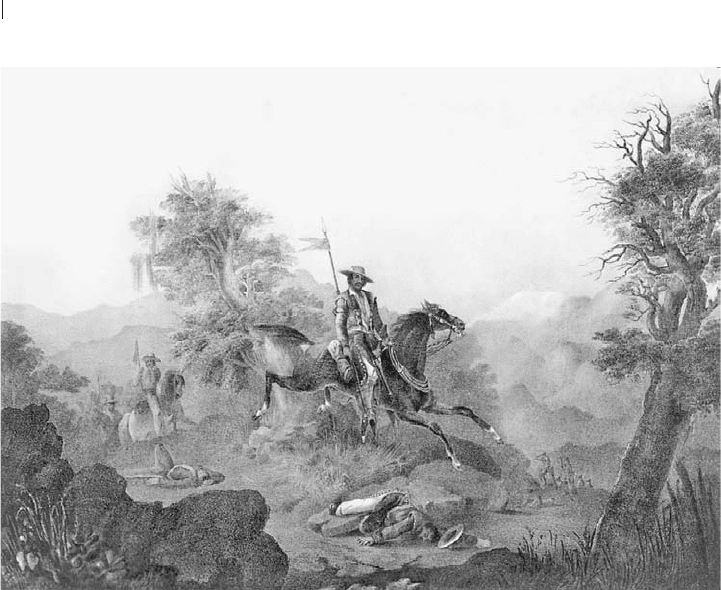

Guerrilla warfare, or hit-and-run attacks on small parties of soldiers and supply trains, was a

frequent Mexican tactic during the Mexican-American War. Here, Mexican guerrillas carry

lances into battle in 1848. (Library of Congress)

Tejanos

“Tejano” is a term t hat has come to be widely employed for people of Mexican

descent living in Texas. The word was first employed as early as the 1820s, when

Mexican officials used it to describe the population of the state of Tejas, and its

usage by Tejanos and non-Tejanos alike became a commonplace in the second half

of the 20th century.

The origins of the Tejano population are the Spanish settlements established in

present-day Texas during the 18th century, but the Tejano community has been

continuously influenced by Mexican migration and the evolution of Mexican soci-

ety. Since the annexation of the Republic of Texas in 1845, Tejanos have been part

of the larger Mexican American and Hispanic or Latino populations of the United

States. The historical experiences of Tejanos have thus been shaped by regional,

national, and transnational forces.

Tejanos were a small minority of the Republic of Texas upon its founding in

1836 . Most lived in the triangle between San Antonio, Laredo, and Brownsville,

generally referred to as “South Texas,” which in turn became one of the areas of

greatest Mexican-descent population in 1848, when Mexico ceded its northern ter-

ritories to the United States with the latter’s victory in the U.S.-Mexico War. Natu-

ral increase and migration from the Mexican northeast during the second half of

the 19th century ensured a steady growth in the size of the Tejano population.

By 1900, Tejanos were the center of gravity of the entire Mexican American pop-

ulation. In 1920, for example, there were more people of Hispanic descent living

in Texas than in California, New Mexico, and Arizona combined. (It was not until

the 1950s that California surpasse d Texas as the state with t he largest Mexican-

descent population). Tejanos continued to comprise a greater and greater percent-

age of the Lone Star State’s population, more than 30 percent by 2000. Demogra-

phers estimate that Hispanics will be a majority of the Texas population by 2050.

Although their ancestors were the founders o f Texas, Tejanos have been sub-

jected to marginalization, oppression, and discrimination by the state’s domin ant

Anglo-American population. Tejanos living in east Texas were expelled and sub -

jected to mob violence in the 1830s and 1840s, despite being guaranteed the rights

of U.S. citizens by the treaty ending the U.S.-Mexico War. In South Texas and

many other parts of the border region, however, they remained a majority well into

the 20th century, and continued to exercise substantial political power despite their

increasing economic marginalization. The early 20th century saw a decline in their

status. B y then, vast majority of Tejanos experienced U.S. society as a racially

oppressed working class, subjected to effective political disfranchisement, occupa-

tional discrimination, and systematic residential segregation. The extreme racial

Plan de San Diego (1915–1916) 735

violence of the Plan of San Diego of 1915–1916 may be the nadir of the Tejano

experience.

Tejanos sought to defend their rights and enhance their status in a wide range of

ways, ranging from migrating out of the state (which hundreds of thousands did

over the course of the 20th century), to labor strikes, to the formation of political

organizations, most notably the League of United Latin American Citizens

(LULAC), founded in 1929.

—Benjamin H. Johnson

Further Reading

DeLeo

´

n, Arnoldo. The Tejano Community, 1836–1900. Albuquerque: University of New

Mexico Press, 1982.

Montejano, David. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986. Austin: Uni-

versity of Texas Press, 1987.

Texas Rangers

Formally established in 1835 as a state law enforcement agency, the Texas Rang-

ers for the next century mixed the characteristics of a volunteer militia and a pro-

fessional paramilitary organization. In the 19th century, the constabulary was a

critical way for Lone Star authorities to assert control over restive populations,

ranging from Mexicans and Tejanos, to independent Indians, to disgruntled white

ranchers and farmers. The force, which at its largest size included more than 500

enlisted men led by a small officer corps, was under the command of an adjutant

general appointed by the state governor.

The Rangers played important roles in most of the significant episodes of civil

unrest in 19th- and early-20th-century Texas. Ranger battalions, for example,

clashed with native peoples in North Texas and Indian Territory in the 1850s.

Together with the U.S. Army, they fought the forces of Tejano rebel Juan Cortina

in South Texas in 1859 and 1860, returning to the region after the civil war to

police a still-restive border. Rangers were critical to the breaking of the massive

1886 Southwe st Strike ag ainst the Missouri-Pacific netwo rk, a nd a strike of coal

miners in Thurber two years later, when Adjutant General W. H. King vowed t o

crush labor organizers “with the mailed hand” (Graybill 2007, 177). The Rangers

helped to secure the dominance of large, corporate cattle ranches in much of the

western portions of the state by suppressing labor unrest by cowboys and small-

time ranchers (many of whom turned to cutting the fences of large ranches that

they felt had seized their own land or illegally restricted access to water supplies).

736 Plan de San Diego (1915–1916)

Texas’ Mexican-descent, or “Tejano,” population often bore the brunt of Ranger

violence. For much of the period from 1848 to 1910, the bulk of the force was

deployed to the border region, especially the Nueces Strip (the area between t he

Nueces River and the Rio Grande), where a substantial and entrenched population

resented and resisted Anglo racial chauvinism and economic dominance. Here,

Ranger-administered justice was generally arbitrary and brutal, as in 1875 when

legendary Ran ger captain Leander McNelly killed a dozen Hispanics sus pecte d

by Anglos of cattle the ft and stacked their bodies in Brownsville’s plaza. Ranger

N. A. Jennings later boasted that along the border the force had a “set policy of ter-

rorizing the residents at every opportunity ...to let no opportunity go unimproved

to assert ourselves and override the ‘Greasers’ ” (Jennings 1899, 71).

This wanton violence reached a new level of intensity in 1915–1919, during and

in the aftermath of the Plan of San Diego uprising. Here, Texas Rangers, their

ranks augmented by emergency measures that allowed for the enlistment of unpaid

“Special Rangers,” played a key role in the violent response to the Plan of San

Diego uprising, engaging in numerous murders and reprisals. One Ranger captain

even threatened state representative J. T. Canales, whose charges that Rangers had

killed scores and perhaps hundreds, led to several weeks of hearings at the state

legislature in early 1919.

Since the Plan of San Diego, the Rangers have shed some of their distinctive

characteristics and reputation for anti-Mexican violence. The constabulary was

dramatically reduced in size in the 1920s and incorporated in t he newly formed

Department of Public Safety in 1935 as a smaller, more professional investigative

force. In the 1960s, however, the Rangers again found themselves at the center of

Anglo-Mexican conflict, playing controversial roles in strikes by Mexican agricul-

tural laborers and in political mobilizations associated with the Chicano

movement.

—Benjamin H. Johnson

Further Reading

Graybill, Andrew. Policing the Great Plains: Rangers, Mounties, and the North American

Frontier, 1875–1910. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Jennings, Napoleon August. ATexasRanger. New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1899. Repr.,

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Utley, Robert. Lone Star Justice: The First Century of the Texas Rangers. New Yo rk:

Oxford University Press, 2002.

Utley, Robert. Lone Star Lawmen: The Second Century of the Texas Rangers. New York:

Oxford University Press, 2007.

Plan de San Diego (1915–1916) 737