Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chinese Immigrants

The Chinese reached America in time to pa rticipate in the 1 849 California Gold

Rush, and from there th ey moved eastward to gold mining regions throughout

the West and in smaller numbers into the American East, totaling some 300,000

prior to their exclusion in 1882. Most Chinese immigrants left the provinces sur-

rounding Canton in southeastern China, fleeing famine and civil strife between

the 1840s and 1860s and seeking the relatively high ages that the industrializing

United States offered. Chinese immigr ants participated in several of the cardinal

events of U.S. history: the California Gold Rush; the construction of the transcon-

tinental railroad; and the development of the mineral and agricultural U.S. West.

Chinese immigrants faced a great deal of nativism and racism, however, which

eventually resulted in the codification of anti-Chinese racism in the 1883 Chinese

Exclusion Act (renewed in 1892 and made a permanent feature of immigration

policy in 1902). In California, foreign miners’ taxes and alien land laws eventually

cut the Chinese out of the gold rush. In other mining regions of the U.S. West, the

Chinese had been largely excluded from the higher-paying jobs in mines and

597

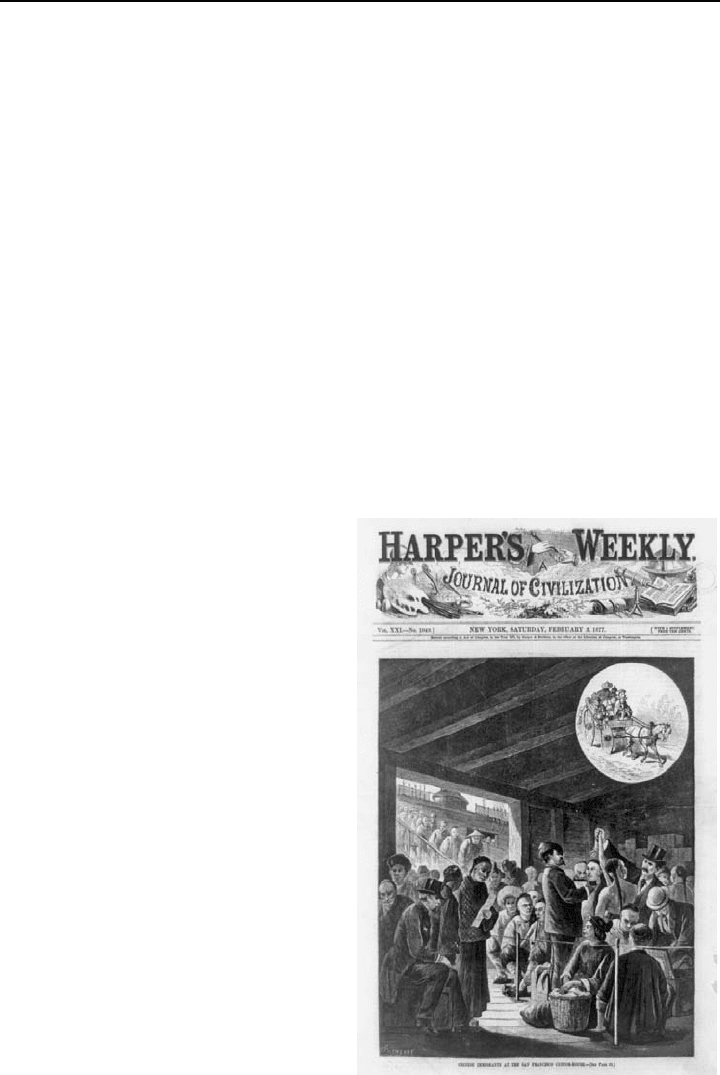

Harper's Weekly illustration of Chinese

immigrants at the San Francisco Custom

House in 1877. (Library of Congress)

relegated to picking over the exhausted claims of white miners or serving as

unskilled laborers. Across the United States, Chinese immigrants faced a racially

segmented labor structure that placed them at the bottom. Nativists, many of them

members of unions like the oth erwise-tolerant Knights of Labor, disparaged

Chinese physical features, clothing, food, language, and customs in ways that cat-

egorized the Chinese as inferior and as a threat to the white working class. News-

papers frequently carried derogatory references and lurid descriptions of

Chinatown opium dens, bordellos, and gambling houses.

Predictably, racism and xenophobia led to violence as anti-Chinese riots

became increasingly commo n across the U.S. West. In 1875, the Union Pacific

Railroad Company first hired Chinese as strikebreakers in its Rock Springs mines

in the Wyoming Territory. The bitterness this caused between the (largely

immigrant) white miners and the Chinese festered for a decade before exploding

in the fall of 1885, when on September 2, an armed white gang attached Chinese

miners, ki lling 28 and expelling several hundred from the town. Riots in Seattle,

Washington; Denver, Colo rado; and other regions of the West drove the Chinese

to the safety of large cities such as San Francisco.

—Gerald Ronning

Further Reading

Chang, Iris. The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. New York: Penguin, 2004.

Saxton, Alexander. The Indispensible Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in

California. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.

Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor was the first truly national labor organization in the United

States. Established as the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor in

Philadelphia on Thanksgiving Day, 1869, it was a fraternal brotherhood of all pro-

ducers, irrespective of most occupations,that promoted education and agitation to

create a new society based upon cooperati on, rather than conflict and confronta -

tion. Under the leadership of its first grandmaster workman, Uriah Stephe ns

(1821–1882), the organization not only followed a policy that to injure one is the

concern o f all, but also a mason-like ritualistic secrecy. This latter policy was

abandoned by its second gra nd master workman, Terence V. Powderly (1849–

1924), in 1881. The economic downturn in 1877 helped enlarge the organization;

by 1879, there were over 23 district branches, known as assemblies, as well as

598 Seattle Riot (1886)

1,300 l ocal branches. Eventually, the Knights of Labor became an internationa l

organization with branches in Australia, Canada, Britain, and Belgium.

During the troubled 1880s, the organization’s concept of an all-inclusive

union seemed to offer an effective vehicle for l abor solidarity, but Powderly’s

continued opposition to strike action gradually weakened its influence. However,

the loose asse mbly system al lowed some branches to take part in noteworthy

strike action; against Western Union in 188 3, the Unio n Pacific Railroad in

1884, and more spectacularly against Jay Gould’s Southwestern Railroad in

1885. This later successful strike acted as an initial recruiting sergeant for the

Knights of Labor, whose membership rapidly increased to 700,000 in 1886.

The Knights of Labor actively campaigned for an end to child l abor, equal pay

for men and women, the need to create worker cooperatives, and a national

graduated income tax as well as the nationalization of such industries as the

railroads and the telegraph system. They also campaigned to end c ontinued

Chinese emigration to the United States, which resulted in the Chinese

Exclusion Act of 1882. Their part in the p rotec ted strike against the McCormick

Harvest Company in 1886 resulted in their involvement in the Haymarket Square

Riot in Chicago on May 3, 1886.

The Knights of Labor were not directly respon sible for the Hay market affair,

esp ecially the bombing of the next day, and the many deaths this entailed, but it

caused Powderly problems. Public revulsion against the violence, which the press

extended to the Knights themselves, was gradually replaced by the revulsion felt

toward Judge Joseph E. Gray’s punitive prosecution of eight anarchists thought

to be involved, men Powderly labeled beasts. His later involvement in ending a

series of strikes dramatically led to a decline in membership a s more skilled,

union-minded members drifted into the American Federation of Labor, and even

later into the Industrial Workers of the World. By 1890, the Knights had fewer than

100,000 members, a dramatic decline that could not be stemmed by its own brief

alliance with the dynamic Populist Party, or Powderly’s replacement by James

Sovereign in 1893, Despite its rapid decline, the Knights of Labor’s universal wish

to unite all workers continued to influence the new unionism of the late 1890s and

early 20th century.

—Rory T. Cornish

See also all entries under Great Railroad Strikes (1877); Haymarket Riot (1886); Seattle

Riot (1886).

Further Reading

Fink, Leon. Workingmen’s Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics.

Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983.

Seattle Riot (1886) 599

Hild, Mathew. Greenbacks, Knights of Labor and Populist: Farmer-Labor In surgency in

the Late Nineteenth Century South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

Phelan, Craig. Grand Master Workman: Terence Powderly and the Knights o f Lab or.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Weir, Robert E. B eyond Labor’s Veil: The Cu lture of the Knights of Labor. University

Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996.

600 Seattle Riot (1886)

Wounded Knee I (1890)

The massacre of between 146 and 300 Minneconjou and Hunkpapa Lakota

(Sioux) at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, December 29, 1890, was the

sharpest and most deadly engagement in a campaign, adopted by the U.S.

government, to suppress an ecstatic religious reviva l among Native Americans,

newly confined to reservations and longing for a return to the life they had previ-

ously known. The clash of American culture against the culture of the Great Plains

nations, influenced by disputes within American politics and the American mili-

tary as well as within and between various branches of the Lakota, produced a pat-

tern of distrust, misunderstanding, misjudgment, a nd hostility, which had a

disastrous result. (The words Lakota an d Sioux refer to the same people: French

explorers picked up the word Sioux, meaning enemies, from tribes at war with

the people who called themselves Lakota, meaning allies. Their word for the peo-

ple who called themselves “white” was wasicun, which makes no reference

to color.)

What agitated Indian Bureau inspectors and army officers across the Rocky

Mountains and western Great Plains was the Ghost Dance, inspired and taught

near Walker Lake, Nevada, by a Paiute named Wovoka, often referred to as the

Messiah. His teaching was an ecstatic religious revival, bor rowing a great de al

from evangelical, millenarian, and pentecostal Christianity. Wovoka taught that

God had made the earth, and sent Christ to teach the people, but white men had

rejected him, leaving scars on his body, so he returned to heaven. Now he

had returned to earth as an Indian. The next springtime, the earth would be covered

with new soil, which would bury all the white men, or roll them b ack to the east

whence they came. All Indians who danced the Ghost Dance would be taken up

in the air while the wave of new earth was passing. Then, they would be set down

and joined by the ghosts of their ancestors. The land would be covered with sweet

grass, running water, and trees, with great herds of bison and wild horses. The

Messiah also taught that sacred garments, perhaps adapted from Mormon tradi-

tion, known as Ghost Shirts, would protect the wearer from any bullets.

Historians still debate whether there was a component of insurrection in the

activities of traditionalists in the Lakota tribes, or whether participants in

the Ghos t Dance were passively waiting for God and their Messiah to deliver the

new ea rth they desired. The mere fact that all f unctions of d aily life ceased, that

601

the rituals of the new faith were outside the control of the Indian Department,

frightened agents on the reservations, and alarme d military chains of command.

Dancers worked themselves into an exhausted state of self-hypnosis, collapsed,

hallucinated, and when revived, told of new visions of the Messiah and the world

to come. The vision that all the wasicun would soon be gone was itself considered

ominous. Efforts to s top the dancing were disdainfully ignored, met with angry

rejection, or resulted in large bands of devotees leaving established communities

for remote places where they hoped to be left alone. The military were aware that

since settling on the reservations, large numbers of Lakota had purchased the

latest-model Winchester rifles, and were probably better armed than at the time

of the Little Big Horn battle, which destroyed General George Custer’s 7th

Cavalry. Not all members of the Lakota bands joined or appreciated the new

revival, either. After it was over, Oglala chief Red Clo ud, who had not supported

the Ghost Dance, said “The white men were frightened and called for soldiers.

We had begged for life, and the white men thought we wanted theirs.”

Wovoka’s initial teaching was pacifist. He taught that followers of his vision

must be industrious, honest, virtuous, and peaceful. He had lived with a rancher

named David Wilson and his family in Nevada for many years, acquiring the

Anglicized name of Jack Wilson, a nd was present during readings aloud from

the family Bible. He had also worked for two years or so harvesting hops in Cali-

fornia, Oregon, and Washington. During this time, he came into contact with a

reli gious revival among Native America n nations called the Shakers—different

from the Anglo-American faith of the same name. From the Shakers’ mix of

Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, and pagan traditions, he may have drawn another

component of his own later teachings. During the 1880s, Wovoka was a respected

shaman among the Paiute. His apocalyptic vision of a new earth came to him at the

time of a solar eclipse, January 1, 1889.

In Octob er 1890, a Min neconj ou Lakota named Ki cking Bear returned to the

scattered Lakota reservations from Nevada with news of the Ghost Dance. He

had traveled west by railroad with Short Bull and nine other Lakota. He had met

hundreds of Indians, speaking dozens of different tongues, who all came to hear

the Messiah and learn the dance. Upon their return, they taught the dance at the

Cheyenne River, Rosebud a nd Pine Ridge reservations, located in South Dakota.

The venerable Hunkpapa spiritual leader, Tatanka Yotanka (Sitting Bull), invited

Kicking Bear to come to the Standing Rock reservation to explain the Ghost

Dance. Sitting Bull is reported in many histories as skeptical of the new faith. He

may have doubted that dead men and women could return to life. He had heard

that agents at some reservations were bringing soldiers in to stop the ceremony.

He would not have wanted soldiers coming to frighten his people, nor did he want

to risk the possibilit y of shooting. (Exactly what Sitting Bull thought has to be

602 Wounded Knee I (1890)

inferred from a very sparse record, since he did not set forth a detailed program to

anyone.) However, people at Standing Rock had heard a good deal about the new

dance, and were afraid that if they did not join in, the Messiah would pass them by,

so that they would disappear at the time of the promised resurrection. Some his-

torical accounts insist that Sitting Bull actively promoted the Ghost Dance, presid-

ing over d ances from a specially built lodge 100 feet in front of his cabin.

Whatever the motivations, Kicking Bear was invited to remain at Standing Rock,

teaching the band living there the Dance of the Ghosts.

The death of Sitting Bull was one of the first results of military intervention. By

the time Kicking Bear returned from Nevada, both civilian and military chains of

command, from Washington down to local agents and officers, had determined

that the Ghost Dance must be stopped. If the revival did not incite Indians to rebel-

lion, at the least it would encourage them to resist the ways of “white” civilization.

Indian policy at the time was well represented by the stated purpose of Captain R.

H. Pratt, director of the Carlisle Indian School in Penns ylvania: “Kill the Indian,

save the man.” The measures to be used were not at first specified, leaving a great

deal up to the discretion of the military chain of command, and of agents and offi-

cers on the scene. A former agent, Dr. Valentine McGillicuddy, dispatched to Pine

Ridge reservation to investigate, advised that the dancers should be left undis-

turbed. “If the Seventh Day Adventists prepare their ascension robes for the sec-

ond coming of the Savior,” he observed , “the United States Army is not put into

motion to prevent them. Why should not the Indians have the same privilege? If

troops remain, trouble is sure to come.” That advice came too late. Standing Rock

reservation agent James “White Hair” McLaughlin had railed that “A more perni-

cious system of religion could not have been offered to a people who stood on the

threshold of civilization.” The agent at Pine Ridge, Daniel Royer, loudly instructed

Oglala on that reservation to cease the Ghost Dance. Not everyone at Pine Ridge

joined in the Ghost Dance, but those who did ignored the political appointee,

who owed his job to friendship with South Dakota senator Richard Pettigrew, call-

ing him “Young-Man-Afraid-of-his-Indians.” Royer, who had no skills, experi-

ence, or qualifications for the position, frantically called for soldiers to prevent

what he reported would be a violent uprising, adding that he was “at the mercy

of these crazy dancers.”

General Nelson “Bear Coat” Miles, commanding the Department of the

Missouri from headquarters in Chicago, ordered a total of 5,000 soldiers from

various commands into position at the Pine Rid ge and Rosebud agencies on

November 17, 1889, and along rail and telegraph lines south and west of the reser-

vations. Frightened and offended by the presence of the soldiers, Kicking Bear and

Short Bull moved with their followers to a mesa on one corner of the Pine Ridge

reservation, known as the Stronghold. This was a triangular extension of a

Wounded Knee I (1890) 603

formation called Cuny Table, about three miles by two miles in dimension, con-

nected by a path wide enough only to permit one wagon to pass. Three t housand

ghost dancers j oined them there. Other dancers camped in the nearby Badland s,

where they hoped to be left alone u ntil the promised resurrection. On Novem-

ber 20, the Bureau of Indian Affairs directed that all agents at Indian reservations

should telegraph the names of “fomenters of disturbances,” meaning those who led

or taught the Ghost Dance. An assembled list was transmitted to Miles, where he

noticed Sitting Bull’s name among those reported. Miles jumped to the conclusion

that Sitting Bull was the primary individual to blame for the Ghost Dance among

the Lakota, and ordered his arrest. Agent McLaughlin, Brigadier Thomas H.

Ruger, comma nding the Departme nt of Dakota, and Lieutenant Colonel William

F. Dunn, commanding at Fort Yates, had all recommended Sitting Bull’s arrest in

early November. As early as October, McLaughlin had reported that the real power

behind the “pernicious system of religion” at Standing Rock was Sitting Bull.

Further, McLaughlin reported, inaccurately, that Sitting Bull was about to joint

the dancers assembled at the Stronghold.

Generally, Miles favored any necessary arrests being made after colder weather

and snow had arrived, when there would be less disturbance. Sitting Bull had great

popularity among both wasicun Americans and among his own people. All visitors

to the reservation wanted to meet him—even those who found his continued pres-

tige a potential threat. He had been invited t o the driving of the last spike in the

Great Northern Railroad in 1883, and taken on a trip to St. Paul, M innesota. In

1885, he had traveled with William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West Show.

Returning to his home, he had been a bulwark of opposition to breaking up the

substantial lands reserved for the Lakota by treaty in 1868—only 22 of the

Hunkpapa at Standing Rock signed the proposed cession of nine million acres at

50 cents an acre. By treaty, the seven Teton Lakota tribes retained approximately

the western half of South Dakota as their own. By 1889, three much smaller

chunks, separated by land opened for settlement, were all that remained. General

George “Three Stars” Crook’s eventual success at getting around Sitting Bull’s

refusal, and breaking up the reservation, was a significant background to the

despair that inspired devotion to the Ghost Dance.

Miles, knowing that a violent arrest of someone of Sitting Bull’s stature would

cause upheaval, tried to have Buffalo Bill Cody invite him to Chicago. Cody was

one of the few wasicun Sitting Bull trusted, but agent McLaughlin did not trust

Cody, and he had the orders rescinded. Colonel Drum at Fort Yates received orders

to “secure the person of Sitting Bull.” It took until December 15 to move 43 Indian

police, commanded by Lieutenant Bull Head, into position around his cabin.

Awakened, Sitting Bull agreed to go, but outside his home found Ghost Dancers

and other Hunkpapa living at Standing Rock, determined not to let him be ta ken,

604 Wounded Knee I (1890)

who outnumbered police four to one. In an exchange of fire that erupted when one

dancer pulled out a rifle and wounded Bull Head, his sergeant, Red Tomahawk,

shot Sitting Bull through the head. The Hunkpapa, deprived of their most

respected leader, fled to the Ghost Dance camps, or to other reservations. About

100 joined a Minneconjou band led by Big Foot, camped near Cherry Creek.

It was Big Foot’s band that was about to bear the brunt of the confused military

response to the Gh ost Dance revival among the Lakota. Genera l Miles had Big

Foot high on his list for arrest. Lieutenant Colonel Edwin V. Sumner, assigne d to

keep Big Foot and his combined band of Minneconjou and Hunkpapa under obser-

vation, reported that without exception, he “seemed not only willing but anxious to

obey my order to rema in quietly at home” and mad e an “extraordinary effort to

keep his followers quiet.” In the absence of explicit orders to make an arrest,

Sumner refrained from doing so. Why Big Foot left his assigned area is not clear.

Miles thought he was going to join the Ghost Dancers at the Stronghold. In fact, he

went the other way, toward Pine Ridge, where he said he had been asked to resolve

some intertribal disputes. Big Foot was known as a good negotiator and peace-

maker. Pine Ridge was an Oglala agency, where the oldest chief, Red Cloud, was

suspecte d of being a “fomenter,” since he opposed many “reforms” pressed upon

him by the U.S. government, but he never had anything to do with the Ghost

Dance. Big Foot said he had been offered 100 horses to resolve some disputes

within the Pine Ridge community. It took t he army 11 days to find him, because

they tried to intercept him moving west when he was moving east. So the soldiers

were looking for him in the wrong area.

Miles, however, was convinced that Big Foot was one of the key lea ders

“fomenting disturbances.” Most of the surviving members of the band were

women who had lost husbands, fathers, brothers, or sons in battles of the pre-

vious 15 years. They danced constantly and ecstatically in hope of bringing

the dead warriors back to life. In fact, by this time, most of the routine of daily

life had ceased for many Lakota, who were doing the Ghost Dance all day and

most of the night. Big Foot did have problems restraining a number of younger

men, who if not anxious to fight, were at least resistant to any kind of surrender.

Moving his band from Cherry Creek to Red Cloud’s Oglala band at Pine Ridge,

Big Foot was riding in a wagon suffering from pneumonia, hemorrhaging and

coughing up blood, when the Minneconjou and Hunkpapa were intercepted by

four troops of 7th Cavalry commanded by Major Samuel Wh itside. The officer

told Big Foot he had orders to take him to a cavalry camp near Wounded Knee

Creek. The younger men in the band argued strenuously against a ccepted this

direction from Whitside, but Big Foot concluded he could not keep his followers

safe if he resisted, and his decision prevailed. He told Whitside they would pro-

ceed as directed.

Wounded Knee I (1890) 605