Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

sometimes differed from men’s, an d they could not count on men to represent

them adequately when writing property and child custody laws.

Though the quest for suffrage gradually became the centerpiece of the women’s

movement, reformers of the 1840s and 1850s sought myriad other reforms in

women’s social, legal, and p olitical position. One of the movement’s most basic

themes was the need to expand employment opportunities for women. Reformers

sought to professionalize teaching a nd nursing, making them both more respect-

able and more remunerative, and to open careers in medicine, law, and the clergy

to women. Elizabeth Blackwell became the Un ited States’ first female physician

in 1849; her sister Emily followed her into the field a few years later, and together

they founded the New Yo rk Infirmary for In digent Women and Children. Their

sister-in-law Antoinette Brown Blackwell, who was ordained in the

Congregational Church in 1853, was the first female pastor in a mainstream Prot-

estant denomination. Many of the landmark writings of the early women’s move-

ment focused on the contributions women could make to society if they gained

access to better education and a broader range of careers. Margaret Fuller’s

Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845) encouraged women to develop their

intellects as fully as men did, while Caroline Dall’s The College, the Market, and

the Court; or Woman’s Relation to Education, Labor, and Law (1867; originally

delivered as lectures in 1859–1861) called for a massive expansion of economic

opportunity.

Another question that absorbed antebellum women’s leaders was how women

could preserve their individual identity within the context of marriage. Some early

feminists omitted the promise to obey from their marriage vows, as Amelia Jenks

did when she married Dexter Bloomer in 1840. The power couple Lucy Stone and

Henry Blackwell went further. At their 1855 wedding, they read a statement in

which they critiqued the laws that constrained married women’s authority over

their own bodies, property, and children. Blackwell formally renounced his supe-

rior privileges as husband, granting Stone control of her body and the freedom to

live where she wished. Stone retained her maiden name. The “Wedding Protest”

was printed in the papers, just as Stone and Blackwell hoped.

One of the most important ways in which married women could retain distinct

legal identities was by winning the right to control the property they brought to

marriage and the wages they earned while married. The first married women’s

property acts, passed in Arkansas Terr itor y in 1835, in Mis sissi ppi in 1839, and

in several other states in the 1840s, merely stated that wives’ property could not

be sold to pay their husbands’ debts. These laws appear to have been passed in

response to the Panic of 1837 and the widespread economic uncertain ty that

ensued. Wives’ right to maintain separate estates was first legislated in New York

in 1848; in 1855, Massachusetts be came the first state to grant married women

476 Women’s Movement (1870s)

the right to keep their own earnings. Ernestine Rose, who as a teenager in Poland

had gone to court to recover property left her by her mother, and subsequently

promis ed away by her father as her dowry in an arranged marriage, was an early

leader of the effort to reform property law.

Economic rights were intertwined with the question of divorce, as economic

pressures could keep women in unhappy or violent marriages even if the law did

not. Most states (with the exception of South Carolina) permitted divorce, but

the grounds for d ivorce were few, and state legislatures granted divorces on an

ad hoc basis. Jane Swisshelm, a newspaper editor who divorced her husband in

1857, was an early advocate of more liberal divorce laws, and Elizabeth Cady

Stanton wrote articles for the feminist periodicals Una and Lily in which she advo-

cated women’s right to divorce. Stanton’s writings drew fire from more

conservative reformers such as Horace Greeley, who supported women’s suffrage

but feared that easier access to divorce would pave the path to free love and social

chaos. Antoinette Brown Blackwell likewise condemned divorce even as she

called for women’s suffrage and improved ed ucat i onal and career opportuniti es.

The antebellum women’s movement did not achieve a consensus in favor of

divorce rights as it did on other prominent issues, such as education, married wom-

en’s property rights, and suffrage.

The Civil War was a major t urning point in the history of the women’s move-

ment. It spawned conflicts over strategy and race that fractured the movement

for at least a generation. In the 1850s and early 1860s, leaders of the women’s

movement campaigned aggressively to end slavery. During the war years, the

Women’s Loyal National League (founded by Susan B. Anthony, Stanton, and

Stone, among others) collected 400,000 signatures on a petition to outlaw slavery

by constitutional amendment. Once slavery had been abolished, women’s leaders

expected political rights for women to advance in tandem with political rights

for freedmen. Lucy Stone founded the American Equal Rights Association

(AERA), which aimed to advance political rights for al l Americans. Its members

were chagrined that the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, penalized states

that denied suffrage to male citizens but not those that denied suffrage to women,

and that the Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, forbade restricting suffrage on

the basis of “race, color, or pervious condition of servitude” but was silent on the

subject of gender.

Women’s leaders, nearly all of whom had been active in the antislavery move-

ment, split bitterly over the question of whether to support the Fifteenth Amend-

ment. In 1869, during the fight for ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment,

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony withdrew from the AERA a nd

organized the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which denounced

the Fif teenth Amendment and urged it s replacement with a co nstitutional

Women’s Movement (1870s) 477

amendment that would enfranchise both men and women of all races. Lucy Stone,

the Blackwell clan, and Julia Ward Howe retaliated by organizing the Americ an

Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which supported the Fifteenth Amend-

ment as a step in the process toward universal suffrage for all Americans. AWSA

was generally more moderate than NWSA and, unlike NWSA, welcomed both

men and women as members. It aimed to secure women’s suffrage by lobbying

state legislatures to extend voting rights to women.

NWSA had a more radical approach, one it dubbed the “New Departure.” Stan-

ton and Anthony, following the lead of Victoria Woodhull, reasoned that the Four-

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments clearly linked voting rights to citizenship. Since

women as well as men were citizens, the Civil Wa r amendments had tacitly

granted women the right to vote. Employing this theory, Anthony attempted to cast

a ballot in Rochester, New York, in 1872. Oth er women’s rights activists, includ-

ing Virginia Minor of Missouri, made similar attempts. Minor’s case eventually

made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in Minor v. Happersett

(1875) that the Fourteenth Amendment’s “privileges and immunities” claus e did

not grant women the right to vote.

Philosophical conflict between NWSA and AWSA, and interpersonal con-

flict between the organizations’ leaders, hampered the women’s movement

throughout the final third of the 19th centur y. This rivalry should not o bscu re

the fact that NWSA and AWSA agreed not only in their ba sic goal—universal

suffrage—but also in prioritizing women’s suffrage above the other aims of the

antebellum women’s movement. To some extent, this development reflected the

progress that had been made since 1848: coeducational public high schools,

wo men’s colleges, and coeducational state universities proliferated in the late

19th century, and women gained access to a wider range of occupations, includ-

ing new fields such as typing, stenography, and social work. One state after

another granted married wome n t he right t o c ont rol the prope rty they brought

to their marriages and the wages they earn ed while married. Many states codi-

fied divorce law and simplified the process of obtaining a divorce; divorce pro-

ceedings increasingly went through the courts rather than through state

legislatures. By the 1870s, a few law schools admitted women, and in 1879,

Belva Ann Lockwood became the first woman admitted to practice law before

the Supreme Court. Bu t women’s lea ders’ redoubled focus on suffrage also

reflected their growing conviction that, in a democratic nation, voting rights

were a necessary precondition to securing other legal reforms. The spread of

universal white male suffrage in the Jacksonian era, followed by the Fourteenth

and F ifteenth Ame ndments, made voting rights an essential component of citi-

zenship, and women could not enjoy full and equal citizenship until they

secured the right to vote.

478 Women’s Movement (1870s)

Unfortunately, postbellum women’s leaders faced a political landscape

unfriendly to their cause. Federal power, which had expanded during the Civil

War and Reconstruction, retreated swiftly after the Compromise of 1877. Neither

of the two major parties cherished a very coherent political ideology; much

power was concentrated in the hands of urban- and state-level political

machines; and federal authorities were reluctant to impose new regulations on

the states. The nation went nearly half a century, from 1870 to 1913, without rat-

ifying a single new amendment to the Constitution. Thus AWSA’s state-by-state

strategy initially proved more practical than the national strategy espoused

by NWSA.

Suffragists won their earliest victories in the West. Wyoming Territory granted

women the right to vote in 1869, Utah Territory in 1870. (Congress, disappointed

that Utah women had failed to vote against polygamy, revoked Utah women’s suf-

frage in the Edmunds-Tucker Act o f 1887. Utah restored women’s suffra ge after

statehood.) By 1 900, four western states had granted women full voting rights:

Wyoming, Colorado (1893), Utah (1896), and Idaho (1896). There are several rea-

sons why western states and territories led the way to women’s s uffrage. The

rough-and-ready nature of frontier life sometimes heightened women’s economic

independence, and some territories offered the vote as an incentive for women to

immigrate. The Populists’ endorsement of women’s suffrage helped win women

the right to vote in Colorado and Idaho. Most importantly, the process of writing

territorial and state constitutions forced westerners to confront new ideas about

citizenship and suffrage. While inertia stalled the women’s movement elsewhere,

the question of women’s suffrage could not be elided in the newly forming western

states.

Meanwhile, a dy namic new organiz ation, th e Woman’s Christian Temperance

Union (WCTU), launched a broader campa ign for social reform that would

include, but not be limited to, women’s suffrage. Nineteenth-century Americans

often perceived temperance as a women’s issue, because male alcoholism left a

trail of domestic violence and poverty in its wake. Founded in 1874 as a women’s

temperance organization, the WCTU built on the tradition of women’s benevolent

clubs to become the largest women’s organization in the late-19th-century United

States. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, it expanded its mission to em-

brace women’s suffrage, equal pay for equal work, and early childhood education,

among other causes (Willard cherisheda“doeverything”philosophy). The

WCTU’s support for women’s suffrage was crucial in making what had once been

a radical position mainstream. By the 1890s, women’s suffrage enjoyed wide sup-

port among middle-class and working-class American women.

In 1887, Lucy Stone called for a merger of AWSA and NWSA. The negotia-

tions were byzantine, but in 1890, the t wo groups finally merged into the

Women’s Movement (1870s) 479

National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). For most of the

1890s, Susan B. Anthony served as president and A nna Howard Shaw as vi ce-

president. In spite of a ble leadership, the movement stalled in the 1890s.

NAWSA was slow to adjust to new social realities. Burgeoning immigration cre-

ated a large pool of urban working women, many of whom had been politicized

by contact with the labor movement and were eager to gain the vote; black

women formed another pool of potential suppo rters. But in their zeal to attract

middle-class white southern women to the movement, NAWSA’s leaders tacitly

accepted their ra cism; black women were pe rmitted to join NAWSA but not to

attend its conventions. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in writing that the nation must

enfranchise educa ted wo men to counteract the ignorant votes of male immi-

grants and freedmen, reflected the elitist mindset of many late-19th-century

suffragists.

Such attitudes persisted even after a new generation of leaders took the helm.

Carrie Chapman Catt, a charismatic speaker and talented administrator, served as

president of NAWSA from 190 0 to 1904 and again f rom 1915 to 1920. Catt

enjoyed advantages, including a college education and a year’s study of law, that

had eluded the earlier generation of women’s leaders, and she cherished a wider

vision, recognizing commonalities in women’s legal and social oppression

around the world. I n 1902, Catt founded the International Woman Suffrage

Association. Yet Catt’s outlook was relentlessly middle class; she was relatively

unaware of the struggles of working women and was slow to take her message to

working-class and immigrant neighborhoods. Others, particularly settlement

house luminaries such as Jane Addams and Florence Kelley, took the lead in

recruiting working-class women to support suffrage. Another innovator was

Elizabeth Cad y Stan ton’s daughter Harriott Stanton Blat ch, who, after a long

residence in England, founded the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women

(later renamed the Women’s Political Union) in 1907 and organized the United

States’ first suffrage parades.

The Progressive Era saw a reinvigorated women’s suffrage movement win fresh

victories in Washington (1910), California (1911), and Oregon (1912). By 191 4,

most Western states had enfranchised women. But even at the height of the

Progressive era, women’s suffrage initiatives failed more often tha n they won. In

some cases—notably in the 1912 Michigan referendum—election fraud defeated

women’s suffrage. This led many of the younger suffragists to question the merits

of NAWSA’s state-by-state strategy. How long, they wondered, would it take for a

nation of 48 states to win women’s suffrage one state at a time?

In 1913, Alice Paul split with NAWSA to found the Congressional Party (later

called the National Woman’s Party), which would pursue the goal of national

women’s suffrage by constitutional amendment. Like Harriott Stanton Blatch,

480 Women’s Movement (1870s)

Paul had lived in England, where the suffrage movement was far more militant

than it was in the turn-of-the-century United States. While in England, Paul

had been imprisoned several times for her activities under t he auspices of the

Women’s Social and Political Union. Paul’s organization adopted the reaso ning

of British suffragists: the political party in power must be held responsible for

failing to enfranchise women. Members of the National Woman’s Party used

attention-getting tactics such as parades, hunger strikes, and picketing the White

House to publicize their views, to the consternation of the more conservative

leaders of NAWSA.

World War I paved the way for universal women’s suffrage in the United States,

as well as in Canada, Britain, and several ot her European count ries. President

Woodrow Wilson, a southern-born Democrat who had long opposed women’s suf-

frage, announced his support for enfranchising women in 1918, citing women’s

contributions to the war effort as the reason for his change of heart. After three-

quarters of a century of active campaigning, women throughout the United States

finally secured suffrage in the Nineteenth Amendment, which was proposed by

Congress on June 4, 1919, and ratified on August 26, 1920.

The ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment permitted American women to

vote in the presidential election of 1920. The first woman to be ele cted t o the

U.S. House of Representatives, Jeannette Rankin of Montana, had already served

her term (1917–1919). The first woman to be elected to the U.S. Senate, Hattie

Caraway of Arkansas, and the first woman member of the Cabinet, Frances Per-

kins, would follow in 1933. (Two women, including Caraway, served in the

Senate by appointment before 1933.) Yet for some, the passage of the Nine -

teenth Amendment was anticlimactic; reformers were disappointed to find that

women did not turn out to vote in large numbers, and that those who did vote

generally voted like their male relatives, rather than composing a discernible

women’s bloc. Carrie Chapman Catt and Maud Wood Park transformed NAWSA

into the League of Women Voters, launching an ambitious program of citizen-

ship education and promoting laws that would benefit women, including the pro-

vision of prenatal care and, in the 1930s, social security.

After the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, the women’s movement

receded for a genera tion. By 1920, m ost of the goal s set out in the Senec a Falls

Declaration of 1848 had been achieved: women could vote and hold public office

throughout the United States; married women could maintain control of their

property; divorce was readily available; and women had access to seco ndary and

higher education and to the professions. The movement needed time to regroup

and define new goals. One of the movement’s most ambitious visionaries was

Alice Paul, who drafted the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which was first pro-

posed in Congress in 1923. But many women’s leaders opposed the ERA, which

Women’s Movement (1870s) 481

would invalidate Progressive laws designed to protect working women, and the

amendment languished until a new incarnation of the women’s movement sprang

to life in the late 1950s.

—Darcy R. Fryer

See also all entries under Civil Rights Movement (1953–1968); Feminist Movement

(1970s–1980s).

Further Reading

Adams, Katherine H ., and Michael L. Keene. Alice Paul and the American Suffrage

Campaign. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Baker, Jean H. Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists. New York: Hill and Wang,

2006.

Flexner, Eleanor. Century of Str uggle: The Wo man’s Rights Mov ement in the Unite d

States. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1996.

Ginzberg, L or i D. Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York.

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Hoffert, Sylvia D. When Hens Crow: The Women’s Rights Movement in Antebellum

America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Isenberg, Nancy. Sex and Citizenship in Antebellum America. Chapel Hill: University of

North Carolina Press, 1998.

Kugler, Israel. From Ladies to Women: The Organized Struggle for Woman’s Rights in the

Reconstruction Era. New York: Greenwood Press, 1987.

Marilley, Suzanne. Woman Suffrage and the Origins of Liberal Feminism in the Un ited

States, 1820–1920. Cambrid ge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Mead, Rebecca J. How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the West ern United States,

1868–1914. New York: New York University Press, 2004.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susa n B . Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds. History of

Woman Suffrage. 6 vols. Rochester, NY: Susan B. Anthony, Charles Mann, 1881–1922.

Ward, Geoffrey C. Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and

Susan B. Anthony. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999.

482 Women’s Movement (1870s)

American Woman Suffrage

Association (AWSA)

The American Woman Suffrage Association was founded in 1869 by Lucy Stone,

Henry Blackwell, Julia Ward Howe, and Josephine Ruffin, prominent leaders in

the women’s rights movement and of the American Equal Rights Association

(AERA). The AWSA was established as a reaction to the development of the

National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and

Susan B. Anthony. Since the first woman’s rights convention, held at Seneca Falls,

New York, in 1848, women’s rights advocates had been working as a singular body

to achieve equal rights under the law for women, including woman suffrage. How-

ever, during the post–Civil War Reconstruction period a divide emerged over ideals.

Many—including Stanton and Anthony—were outraged by the passing of the Four-

teenth Amendment, which defined U.S. citizenship as “male” and extended citizen-

ship to newly freed male slaves and thereby excluded women from the privileges of

U.S. citizenship. In addition, the Fifteenth Amendment, which in 1869 was being

considered by Congress, threatened to further exclude women from the voting pro-

cess by asserting that states could not allow voting discrimination based upon race,

yet still did not mention sex. These two amendments and Elizabeth Stanton’s grow-

ing exhibition of racist views served to widen an already existing divide within the

AERA. Stanton and Anthony first struck out on their own, forming the NWSA. The

establishment of the AWSA, asserting opposing ideals, quickly followed.

While the end goal of both the AWSA and the NWSA was the same—women’s

suffrage—their tactics and principles were quite different. AWSA membership was

open to all—women and men, as well as black reformers. The core focus of the

AWSA was achieving women’s suffrage; they did n ot advocate other women’s

issues s uch as divorce, property rights, education, or employment. They be lieved

once women were granted the vote, they could then affect change on other impor-

tant women’s issues at the ballot box. With headquarters in Boston, the founders

and m embers of the AWSA supported both the Fourteenth and the Fifteenth

Amendments. They joined the growing consensus that enfranchising both freedmen

and women at the sa me time would be too much c hange for politicians and other

opponents to handle at onc e. However, they believed once black males achieved

suffrage rights, women’s suffrage would follow suit. The AWSA strategy for

achieving women’s suffrage was based on state-level campaigns, rather than

federal-level campaigns. They l obbied and campaigned across the country for

referendums granting women’s suffrage to be placed on election ballots and to be

passed by state legislatures. In an effort to get their message out, AWSA officers

483

and members, including their president, Henry Ward Beecher, lectured across the

country. Through their weekly publication the Woman’s Journal,editedbyLucy

Stone, they were able to extend their reach to all corners of the country and abroad.

By 1890 the AWSA had affected little change to the state of women’s suffrage;

the NWSA had no better success. The two groups realized that their efforts were

best served in unity, rather than opposition. The two reconciled and merged to

form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and together

continued their crusade for women’s suffrage.

—Dawn M. Sherman

Further Reading

Baker, Jean H. Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisite d. New York: Oxfor d

University Press, 2002.

Clift, Eleanor. Founding Sisters and the Nineteenth Amendment . Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley

& Sons, Inc., 2003.

McMillen, Sally G. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement.New

York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill. One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage

Movement. Troutdale, OR: NewSage Press, 1995.

Anthony, Susan B. (1820–1906)

Susan B. Anthony was the most famous advocate of women’s suffrage in the 19th-

century United States. She helped organize the women’s movement and, after the

Civil War, spearheaded the national campaign to gain suffrage by means of a con-

stitutional amendment.

Anthony’s support for women’s rights was forged in the crucible of financial

distress. Her father, who managed a cotton mill, lost his livelihood in the Panic

of 1837, and Anthony, who had been educated at a Quaker seminary near Philadel-

phia, taught school for more than 10 years to support her parents and siblings. She

quit in 1849 to manage her family’s farm near Rochester, New York. Through her

family, Anthony met reformers who were active in the antislavery, temperance,

and women’s rights movements, including Frederick Douglass and—in 1851—

Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Anthony’s reform career blossomed after she and Stanton founded the Wom-

en’s New York State Tempe rance Society in 1852. Anthony and Stanto n fused

temperance with women’s rights by emphasizing that women needed the right

484 Women’s Movement (1870s)

to vote on social issues and to divorce alcoholic husbands. Anthony also worked

to secure married women’s property rights, divorced women’s custody rights,

and the expansion of women’s employment opportunities. She remained active

in other reform movements as well, serving as the principal New York State

agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society from 1856 to 1861. During the Civil

War years, Anthony campaigned nationally to secure the passage of the Thir-

teenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery throughout the United States.

Soon after the Civil War, Anthony’s relationship with the freedmen’s civil

rights movement turned sour. She was disappointed that the Civil War amend-

ments did not e nfranchise women and, in some of her writings, cast the enfran-

chisement of black men as a potential threat to the safety of white women. In the

late 1860s and 1870s, Anthony diffused her energy among several endeavors, act-

ing as corres pondin g secretary of the American Equal Rig ht s Association, pub-

lishing a newspaper, The Revolution, and running the National Woman Suffrage

Women’s Movement (1870s) 485

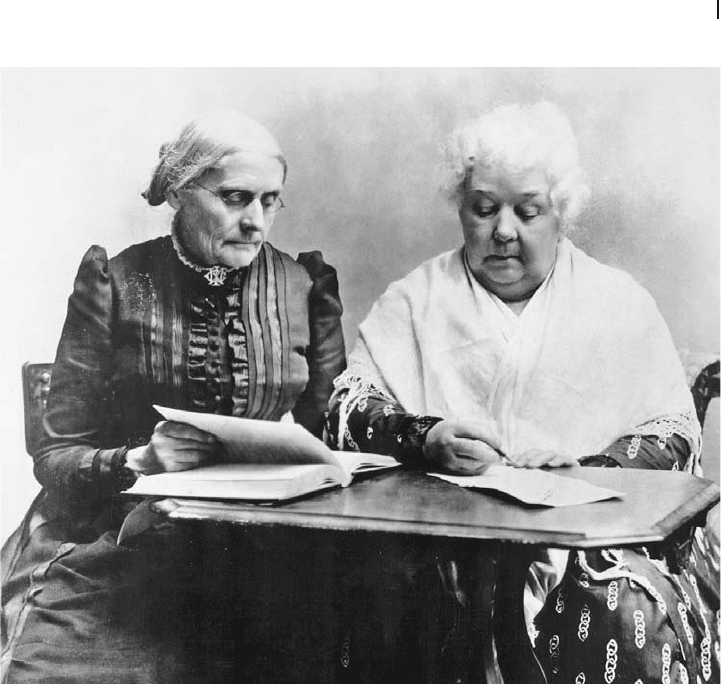

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (right) and Susan B. Anthony, American pioneers in the women's

rights movement. (Library of Congress)