Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

reputable body of people rendered incapable of being serviceable either to themselves or

the community.

2nd. The monies raised by impost and excise being appropriated to di scharge the

interest of governmental securiti es, and not the foreign debt, when these securities are

not subject to taxation.

3rd. A suspension of the writ of Habeas Corpus, by which those persons who have

stepped forth to assert and maintain the rights of the people, are liable to be taken and

conveyed even to the most distant part of the Commonwealth, and thereby subjected

to an unjust punishment.

4th. The unlimited power granted to Justices of the Peace and Sheriffs, Deputy

Sheriffs, and Constables, by the Riot Act, indemnifying them to the prosecution thereof;

when perhaps, wholly actuated from a principle of revenge, hatred, and envy.

Furthermore, be assured, that this body, now at arms, despise the idea of being insti-

gated by British emissaries, which is so strenuously propagated by the enemies of our lib-

erties: And also wish the most proper and speedy measures may be taken, to discharge

both our foreign and domestic debt.

Per Order,

Daniel Gray, Chairman of the Committee

Source: G. R. Minot, History of the Insurrection in Massachusetts (Boston: James W. Burditt,

1810), 82.

A Letter to the Hampshire Herald Listing the Grievances

of the Rebels (1786)

In the following letter sent to the Hampshire Herald in December 1786, Thomas Grover, after

referring to the list of grievances in the previous document, further elaborates on the reforms

that the Shays’ rebels wis hed to see implemen ted. Among thos e changes are r emoval of the

Massachusetts state capital from Boston, the sale of state lands to pay the foreign debt, and

the revision of the state constitution. Many of these measures were passed by the Massachusetts

General Court in the years after Shays’ Rebellion.

Sir,

It has some how or other fallen to my lot to be employed in a more conspicuous man-

ner than some others of my fellow citizens, in stepping forth on defense of the rights and

privileges of the people, more especially of the county of Hampshire.

Therefore, upon the desire of the people now at arms, I take this method to publish

to the world of mankind in general, particularly the people of this Commonwealth, some

of the principal grievances we complain of. ...

224 Shays’ Rebellion (1787)

In this first place, I must refer you to a draught of grievances drawn up by a committee

of the people, now at arms, under the s ignature of Daniel Gray, chairman, which is

heartily approved of; some others also are here added, viz.

1st. The General court, for certain obvious reasons, must be removed out of the

town of Boston.

2nd. A revision of the constitution is absolutely necessary.

3rd. All kinds of governmental securities, now on interest, that have been bought of

the original own ers for two shillings, and the highest for six shillings and eight pence on

the pound, and have received more interest than the principal cost the speculator who

purchased them—that if justice be done, we verily believe, nay positively know, it would

save this Commonwealth thousands of pounds.

4th. Let the lands belonging to this Common wealth, at the eastward, be sold at the

best advantage to pay the remainder of our domestic debt.

5th. Lest the monies arising from impost and excise be appropriated to discharge the

foreign debt.

6th. Let the act, passed by the General Court last June by a small majority of only

seven, called the Supplementary Act, for twenty-five years to come, be repealed.

7th. The total abolition of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas and General Sessions

of the Peace.

8th. Deputy Sheriffs totally set aside, as a useless set of officers in the community; and

Constables who are really necessary, be empowered to do the duty, by which means a

large swarm of lawyers will be banished from their wonted haunts, who have been more

damage to the people at large, especially the common farmers, than the savage beasts

of prey.

To this I boldly sign my proper name, as a hearty well-wisher to the real rights of the

people.

Thomas Grover

Worcester, December 7, 1786

Source: G. R. Minot, History of the Insurrection in Massachusetts (Boston: James W. Burditt,

1810), 82.

Shays’ Rebellion (1787) 225

Whiskey Rebellion (1794)

The Whiskey Rebellion of 1791–1794 in western Pennsylvania was an organized

resistance to a tax on whiskey impose d by the new f ederal government. In many

ways, it was a replay of the Stamp Act crisis of 1765, Shays’ Rebellion of 1786,

and the American Revolution itself. Ideologically, internal taxes created by a dis-

tant central government were seen as fundamental violations of the rights of indi-

viduals to tax the mselves. The Sta mp Act had united the colonists against the

common en emy, King-i n-Parliament. The Whiskey Tax, enacted in March 1791,

united westerners against the new federal government they ha d d istrusted from

the beginning.

Opposition to the excise tax, which had deep roots in the ideology of English

“Country” radicals and their predecessors, had less to do with the tax than in the

means that might be employed to collect it. “Country” radicals like Algernon Sid-

ney, John Trenchard, and Thomas Gordon had warned that this was one of the

most egregious uses of a “standing army”—the intrusion on one’s personal prop-

erty of a permanent military force created to enforce unpopular measures, like

the excise tax. Local control of affairs was seen by many in this school of thought

to be essential to liberty. Power overly concentr ated in a distant and c entralized

national government could be expected to use a standing army for tyrannical pur-

poses. West of the Appalachian Mounta ins, settlers who had come to the region

hoping for some measure of autonomy suddenly found themselves subjected to

the kind of thing they had sought to defeat in the war.

The country around “the Forks,” shorthand for the headwaters of the Ohio at

Pittsburgh, had long suffered from the res istance of Indian peoples to Euro-

American expansion as well as what they perceived as indifference from the state

legislature in Philadelphia. At the front lines of empire, Indian war was their chief

concern, and neither the state government nor the new federal government in New

York had given them much help. Indeed, help with the conquest of the Indians and

acquiring navigation rights on the Mississippi River—at that point prohibited by

the Spanis h—were the only reasons for having a federal government at all that

they could see. Since they did not have access to the port of New Orleans and

the Atlantic market economy, western farmers found that distilling their corn into

whiskey and transporting it over the mountains to Philadelphia or other port towns

was the most cost-effective way to market their crop. Now, that was in jeopardy

227

from a federal government that threatened to take what little profit they made from

their year’s labor.

As bad as that seemed to these weste rn subsistence farmers, it was their more

wealthy neighbors and economic competitors who not only gained an advantage

from the whiskey tax, but who also volunteered to collect it. Moreover, the tax

was c reated, in part, to pay debts-plus-interest incurred to wealthy Americans

during the war—individuals like the wealthy Philadelphia banker and land specu-

lator Robert Morris. It was no secret that Morris was a friend of Alexander

Hamilton, the author of the hated excise that would pay dividends on the war debt

held by Morris and other wealthy Americans. These financiers had welcomed the

young Hamilton into their circle as the d rive for a federal government gell ed in

the late 1 780s. With the Federalist victory in t he battle over t he ratification of a

new constitution, President George Washington had appointed Hamilton to be

the first s ecretary of the treasury. It appeared that Morris and company would be

paid a handsome profit on their investment in the Ameri can Revolution and its

aftermath.

When the war was going badly for the Continentals in 1776, Congress had

offered bonds to investors at 4 percent interest pay able in paper money. Morris

and company were not interested; continental paper would depreciate rapidly,

228 Whiskey Rebellion (1794)

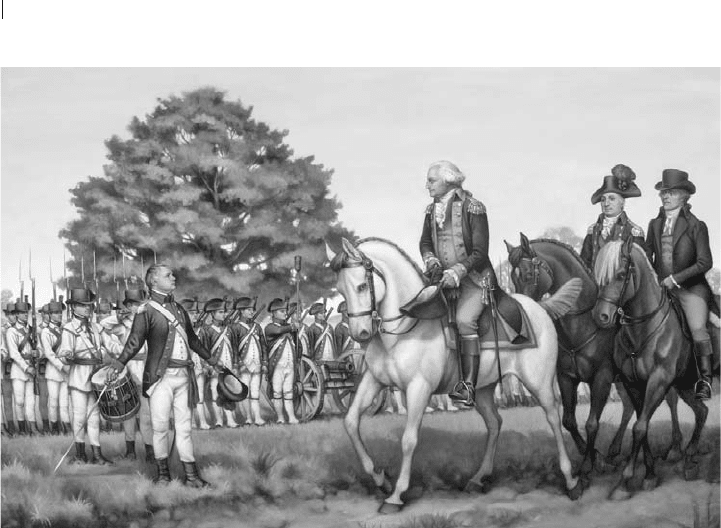

President George Washington and his advisers send Confederation Army troops to pacify

western counties of Pennsylvania during the Whiskey Rebellion, October 1794. (National

Guard)

and indeed, when Congress stopped printing it in 1780, t he value ratio between

paper and coin was 125 to 1. But Morris was a m ember of the Continental

Congress, and as a successful merchant with a far-flung commercial empire of

his own, he w as able to coax the French into loaning Congress the cash to cover

interest on the bonds in so-called bills of exchange. These bills were exchangeable

on the European market for hard currency—silver and gold. This arrangement

made the bonds an attractive investment, and Morris and his associates soon

bought them up—and they bought them up with Continental paper money. Much

of this paper money had been bought up at pennies on the dollar, yet the bondhold-

ers would be paid back with interest in hard money.

Robert Morris wielded great power in the Continental Congress. He and his cro-

nies headed the committees of Finance, Foreign Affairs, and War. He routinely

used c ongressional money for his own investments, and the fact that they were

often profitable kept him in power instead of getting him imprisoned. But now that

the Morris faction held these bonds, issued at 6 percent interest and backed by the

bills of exchange, meant that real wealth was needed to pay for them. This real

wealth would be p rovi d ed through taxation. State governmen ts in the 1780s had

been hesitant to impose an unpopular excise tax and whether a state militia would

even enforce its collection was open to question. With the advent of the new

Constitution, which concentrated power in the federal government, an army osten-

sibly led by President Washington could enforce the payment of an excise tax. The

new secretary of the treasury Hamilton, following a long British tradition of taxing

“vices” to minimize popular opposition, proposed a tax on whiskey. It was passed

by the new Congress on March 3, 1791. One-third of the whiskey distillers in the

United States lived at the Forks. Many of these individuals had fought the British

and their Indian allies on the battlefield without receiving the pay that was still

owed them. Some were paid in the lands west of the mo untains, where Indian s

clung tenaciously to their land base and had no intention of be ing driven away.

Now these people were being ordered to pay a crippling tax so that, as they saw

it, Bob Morris and friends could reap a windfall. The majority had no intention

of paying it or of countenancing the presence of its collectors.

As with the rationalization of excise taxes in England, there was a long history

of resistance to such taxes in folk culture. The majority of westerners were

Scots-Irish, a group that had long struggled against the encroachment of imperial

Britain. Peasant and artisan communities in the pre-modern, English-speaking

world had enforced their standards traditionally through the folk methods of

“skimmington” or “rough music .” When someone repeatedly violated the norms

of the community, a “committee” of self-appointed enforcers, often with faces

blackened and dressed in bizarre clothing, perhaps in drag, would arrive at the

offender’s home, shave his head, strip him naked, ride him around town on a rail

Whiskey Rebellion (1794) 229

while beating on pots and pans and chanting the party’s offenses, finally depositing

him on the outskirts of the community where he was likely beaten and/or tarred

and feathered. This “home remedy” was applied to ta x collectors at the Forks

as well.

In September 1791, such a committee accosted a recently appointed federal tax

collector named Robert Johnson on a lonely road near Pigeon Creek, southwest of

Pittsburgh. Johnson had either ignored or failed to see the notice in the Pittsburgh

Gazette announcing a resolution adopted at a meeting in the nearby town of Wash-

ington to treat tax collectors as public enemies. This group of men, about 15 to 20

in number, faces blacked, many wearing dresses, stripped Johnson naked and

tarred and feathered him. This occurred the same week that many of the perpetra-

tors were attending a conference in Pittsburgh at the Sign of the Green Tree, a tav-

ern on the Monongahela River side of town. The conference was the culmination

of efforts begun that summer to resist the whi skey excise. The first meeting was

at Redstone–Old Fort (present-day Brownsville) on July 27, 1791. Two factions

were emerging in the resistance that overlapped at the Green Tree conference,

those bent on tarring and feathering, and those who insisted on following the rule

of law and democratic-republican principles.

The moderates were led by three notable individuals who were involved in state

and national politics. William Findlay was one, a future gov ernor of the state. Hugh

Henry Brackenridge, who had teamed with Philip Freneau to provide some of the

more radical war propagand a during the revolution, had come to Pittsburgh after

the war to find elbow room and seek his fortune. Also living in the area was Albert

Gallatin, a Swiss immigrant pursuing a land speculation scheme aimed at French

e

´

migre

´

s from that revolution. In 1795, he was elected to the House of Represen-

tativ es, where he expanded his reputation as a formidable opponent of the Hamilton

wing of the Federalist Party. Gallatin would go on to serve as secretary of the

treasury in the Jefferson administr ation. Although Findlay, B rackenridge, and

Gallatin had a moderating effect on the Whiskey Rebellion, at its height, opposing

the outbreak of violence while protesting the excise was not for the feint of heart.

In Kentucky, North Carolina, and northwestern Virginia, the federal

government could find no one to collect the tax. News of this phenomenon was

somewhat suppressed by the Federalist-dominated newspapers to prevent further

rebellion. After all, this was the same kind of protest that Britain had felt in 1765

and 1776. Untaxed spirits from south western Pennsylvania flowed southward to

markets in that region, frustrating those desiring to collect revenue on it. Hamilton

was anxious to deploy troops to enforce the excise, but President Washington and

Attorney General Edmund Randolph opposed the move.

As the boycott of the excise stretched into its second year, the question became

less whether or not to deploy troops , but where to deploy t hem. Washington and

230 Whiskey Rebellion (1794)

Hamilton knew that they did not have the manpower to e nforce the excise a t all

points in the West. While the treasury secretary pondered troop deployments,

Washingto n wrote to the g overnor of North Car olina, and Randolp h stated that

he could find no hard evidence to warrant the prosecution of the frontiersmen.

Supreme Court chief justice John Jay aptly summarized the predicament: the

worst thing that could happen would be for a fed eral military force to be humili-

ated on the frontier. Frontiersmen were veteran warriors, having served in the

Revolution and often having fought the formidable Native Americans to take and

keep the homesteads they now possessed.

By late 1792, Hamilton began to strategize that putting down this “rebellion”

might be accomplished by focusing on one area rather than the entire western fron-

tier. Western Pennsylvania was the closest and most e asily reached by a military

force. Hamilton had allies in the region, most notably John Neville, who had

accepted an appointment as the regional inspector of the excise tax. Neville was

among the wealthiest men in the Forks region. While most of his neighbors were

losing their l and, he was buying it. Neville owned a compound known as Bower

Hill that included 1,000 acres of land, 18 slaves, 16 head of cattle, 23 sheep, and

10 hor ses—an extensive holding in southwestern Pennsylvania. His son -in-law

supplied the local militia with needed goods through government contracts.

Hamilton’s inf ormation about the area largely came from Neville, who d id not

bother to dist inguish the peaceful resistance movement from the violent one.

Neville, with a still that produced up to 600 gallons of whiskey a year, was the

kind of man who benefited from the whiskey tax. Being more acclimated to

the realm of business, people like Neville were favored by Hamilton and taken

more seriously than their lower-class counterparts. Small distillers were at a dis-

tinct disadvantage, operating more on a tr aditional folk culture level than on that

of international business and empire that to Hamiltonians was the coin of the

realm. Unlike pre-modern society, where the affairs of the common folk were

largely left alone, market economics dictated that they be competitive or fall by

the wayside. Small-time operators who were not interested in obtaining large sums

of material wealth represented unwanted competition that needed to be squelched

and, in the Forks region, Neville was happy to oblige.

By 1793, violent opposition to the excise in Pennsylvania had coalesced with

the formation of the Mingo Creek Association. Originating southwest of

Pittsburgh near the village of Washington, their plan was to use the democratic pro-

cess to infiltrate the local militia and depriv e the Federalists of the use of that entity

to enforce the tax. The more radical among them even considered independence,

designing their own flag and entertaining the notion of aid from Britain or Spain.

Other indivi duals were accosted and tarred and feathered. William Faulkner, a

newcomer to the Forks, rented office space to Neville and had his building

Whiskey Rebellion (1794) 231

vandalized for his trouble. The Whiskey Rebels forced Faulkner to eject Ne ville and

publish a notice saying the tax would not be collected on his property. During a

meeting of the Washington County militia in June, an effi gy of “General Neville

the excise man” was displayed and burned. Benjamin Wells, a tax collector residing

in Fayette County, had his life threatened on a couple of occasions and was forced to

turn over his account books and commission to a blackfaced, handkerchiefed “com-

mittee” of anti-excise men. He was also compelled to publish his resignation as col-

lector in the Pittsburgh Gazette. This resistance brought the attention of Hamilton

and Washington to the Forks, but the difference between Pennsylvania and other

regions of the West was not the resistance, but the presence of Neville and his

allies—willing collectors of the excise.

As the seeming head quarters of the tax collector, the compound at Bower Hill

was a symbol of oppression. This view intensified as the events of 1794 unfolded

in southwestern Pennsylvania. In June, U.S. marshal David Lenox was sent to

the area to begin distributing summonses to over 60 distillers who had refused to

comply with the excise law. Lenox distributed a large number of these in three

of the western counties, remaining unmolested apparently because of his position

as a lawman. Hugh Henry Brackenridge, a moderate tax protester who had and

would continue to reign in the violent faction to the best of his ability, entertained

Lenox at his ho me in Pittsburgh. He told Lenox that it was likely because of his

non-association wit h Neville and other pro-excise residents that he had escaped

attack. Nevertheless, when John Neville offered to guide Lenox to serve one last

summons in July, Lenox accepted. This proved to be one of the decisive moments

in the Whiskey Rebellion.

Lenox and Neville made their way to the home of William Miller to serve a sum-

mons. Miller was outraged that he should have to interrupt his seasonal schedule to

go to Philadelphia and likely pay a ruinous $250 fine. The presence of Neville “made

my blood boil” he reported, and Miller refused to accept the summons. As this was

transpiring, men working in the summer hayfields nearby heard that individuals were

being arrested, with the help of the hated Neville, and taken to Philadelphia. While

this was hyperbole, the 30 to 40 men who subsequently confronte d Lenox and

Neville were frustrated and outraged. The presence of a U.S. marshal and the

obvious misinformation confused the group, facilitating the exit of the two excise

enforcers. Lenox returned to Pittsburgh and Neville to his lair at Bo wer Hill.

Meanwhile, the Mi ngo Creek militi a had gathered that same day to answer

President Washington’s call for volunteers to supplement General “Mad Anthony”

Wayne’s army engaging the Indians in the Ohio country. When the rumors of

enforcement action reached these men, it was decided to confront the enforcers,

both thought to have gone to Bower Hill. The militia’s plan was to capture Marshal

Lenox. When they arrived, with “37 gun s,” they surrounded the house. Neville

232 Whiskey Rebellion (1794)

heard them around daybreak and stepped outside to confront them. He warned

them off and fired a shot into the crowd, killing militiaman Oliver Miller. In the

ensuing exchange of gunfire, Neville blew a horn, and his slaves opened fire from

their quarters behind the militia, wounding several of them. The militia retreated

to a place known as Couche’s Fort, where they met with reinforcements and con-

sidered their alternatives.

With the ante upped by Neville’s fatal shot at Miller, the militia felt they had

new rationale for their resistance. For his part, Neville applied for protection from

the local judges but received none, although Major James Kirkpatrick and 10 vol-

unteers from Fort Fayette came to help Neville defend Bower Hill. On July 17, two

days after the original confrontation near William Miller’s farm, about 600 men

accompanied by drums and riding in formation arrived at Neville’s residence.

The leader of the militia, James McFarlane, a Revolutionary War veteran, sent a

notice demanding that Neville surrender, resign his commission, and decline all

further offices related to the excise. Unbeknownst to the militia, Kirkpatrick had

smuggled Neville into a thicketed ravine where he lay in hiding. The major refused

to leave, arguing that if he did, the militia would burn the property. The militia

responded by surrounding the compound, lighting fire to a slave cabin and a barn.

The military managed to get the Neville family out of the house, and a pitched bat-

tle ensued. At one point, M cFarlane thought someo ne had cal led out from the

house a nd ordered a cease-fire, think ing the soldiers wanted to negotiate. When

he stepped into the open, a shot fired from th e house struck him down, killing

him instantly. The militia continued to set fire to the buildings at Bower Hill, with

the exception of a few that the slaves talked them into sparing. Soon the heat

became too intense for the soldiers inside, and they surrendered. The prisoners,

along with Lenox, who had been retrieved from Pittsburgh, were brought to

Couche’s Fort and threatened extensively, although no serious harm was done.

The soldiers were released and Lenox escaped, taking his leave from the area by

floating on a barge down the Ohio River. In the end, the number of casualties

was not clear; several were s erious ly wounded, and there were re por tedly a few

deaths on each side. This was the bloodiest day of the Whiskey Rebellion, and

the blame for it falls at the feet of John Neville, whose patrician attitude and kill-

ing of Oliver Miller caused the escalation of events in July 1794.

The Whiskey Rebellion threatened to expand southward and even eastward

after these events. Liberty poles were raised, and rumors of militias forming as

far east as Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and Hagerstown, Maryland, were rampant. If

the West was to rise up against federalism, now was the time to do it while even

rural people east of the mountains were supportive of their cause. The response

of people in central and eastern Pennsylvania was the catalyst that spurred the

federal government into action.

Whiskey Rebellion (1794) 233