Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

found logs from large white pine trees that had been marked with the broad arrow.

Altogether, there were many logs at the sawmills owned by Richards, Asa Pettee

andDow,and270logs,whichwerebetween17and36inchesindiameter,

were at Clement’s Mill and at the Old Mill Village in South Weare. In the New

Hampshire Gazette of February 7, 1772, some of the offenders were named, and

the government asked them to show cause why their logs should not be seized by

the Crown.

Criminal proceedings began against the owners of the mills, and they were

arraigned at the Court of Vice Admiralty at Portsmouth. The mill owners engaged

a lawyer called Samuel Blodgett from Goffstown, and he started interceding with

Governor John Wentworth in the hope that he would spare the loggers. However,

Wentworth appointed Blodgett as the Surveyor of the King’s Woods largely so that

he would appreciate the nature of the problem. Blodgett urged the sawmill owners

to pay for the logs they had cut down, and 3 men from Bedford and 14 from

Goffstown did so. However, money was owed from Weare.

To enforce the law, Benjamin Whiting, the county sheriff, and his deputy John

Quigly, a rrived in South Weare on April 13, 1772, with a warrant for the arrest

of Ebenezer Mudgett, the lea der of the sawmill owners in Weare. They arrested

Mudgett, but released him on his own undertaking, agreeing to him bringing suit-

able bail in the morning. The two officials then decided to spend the night at the

appropriately named Pine Tree Tavern of Aaron Quimby.

It was not long before news about Mudgett spread around Weare, and many

supporters flocked to his h ouse. There, some o f them offered to provide the bail

for him, but others decided that they could attack the British officials and chase

them out of town. At dawn the following day, they struck.

Very early in the morning of April 14, 1772, Mudgett went over to the Pine Tree

Tavern and woke up Whiting, telling him that he had brought the bail. Whiting

was angry that Mudgett had come so early and started to dress. At that point, some

20 men—all with their faces covered in soot—burst into Whiting’s room and

attacked the two government officials with canes they had made from nearby trees.

They seized the guns of the officia ls and hit Whiting once for every tree that the

sawmillownersweretobefinedover,andtheylefthimbatteredandbruised.

The attackers then dragged the two men down to their horses. They cut off the

manes and tails—and a lso the ears—of the horses that Whiting and Quigly had

used and fo rced both men to mount their horses. A jeering mob hissed as the

men left town.

Whiting then sought help from Colonel Moo re in Bedford, and als o Edward

Goldstone Lutwyche of Merrimack. They assembled a posse, and armed, they

rode back to Weare, where they found that the local population had fled. Eventu-

ally hunting around, th ey found one of the culprits involved in the attack on

184 Pine Tree Riot (1772)

Whiting, and the others were all named and ordered to post bail and appear in

court in due course.

In total, eight men were charged with ri oting and disturbing the peace, as well

as “making an assault upon the body of Benjamin Whiting,” and Timothy

Worthley, Jonathan Worthley, Caleb Atwood, William Dustin, Abraham Johnson,

Jotham Tuttle, William Quimby (brother of the tavern owner Abraham Quimby)

and Ebenezer Mudgett were arraigned before four judges, Chief Justice Honorable

Theodore Atkinson, Meshech Weare, Leverett Hubbard, and William Parker. The

hearing finally took place in September 1772 at the Superior Court in Amherst,

and there the defendants pleaded guilty and were fined 20 shillings each, plus the

cost of the hearing. It is believed that this incident might have been the inspiration

for the use of disguises at the Boston Tea Party in December 1773.

Of the men charged, Timothy Worthley, his brother Jonathan, and William

Dustin all fought the British in the American War of Independence, Timothy

Worthley and Dustin both holding commissions in the C ontinental Army. The

lawyer Samuel Blodgett also served in the Continental Army for the first year of

the w ar, returni ng to Goffstown where he worked on the construc tion of the

Amoskeag Canal. Benjamin Whiting supported the British in the war, had his land

confiscated, and probably died in Canada. Of the justices, Meshech Weare was one

of the people who framed the New Hampsh ire Constitution, which was adopted

in 1776.

—Justin Corfield

See also all entries under Stamp Act Protests (1765); Boston Massacre (1770); Boston Tea

Party (1773).

Further Reading

Brown, Janice (descendant of Jotham Tuttle). “Weare, NH 1772: Rebellion before the

Revolution.” http://cowhampshire.blogharbor.com/blog/_archives/2006/3/20/

1831687.html (accessed November 11, 2008).

Daniell, Jere R. Experiment in Republicanism: New Hampshire Politics and the American

Revolution, 1741–1794. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970.

Pine Tree Riot, April 14, 1772. South Weare, NH: Weare Junior Historical Society, 1972.

Wood, James Playsted. Colonial New Hampshire. New York: T. Nelson, 1973.

Pine Tree Riot (1772) 185

Royal Authority

The Pine Tree Riot of 1772 was a test of royal authority in New Hampshire

whereby local people in a relatively isolated settlement—in this case, the village

of Weare—rejected the authority of the Crown. Although the riot produced only

a short-lived victory, the evident support of the local judiciary in fining the culprits

such small amounts, showed that there were many who might challenge royal

authority, undoubtedly providing inspiration for the more famous Boston Tea

Party in the following year.

In Great Britain, King George III was the unquestioned ruler of the country—

although the elderly and portly Jacobite claimant Charles Edward Stuart (“Bonnie

Prince Charli e”) maintained a court in Rome—but the British constitution was

unwr itten, and it gradually changed and adapted to new circums tances. D isputes

and other matters that arose were decided by precedent and usage. The king ruled

through the houses of Parliament, and laws were passed by the House of

Commons and the House of Lords, with the king giving royal assent. As such,

the king operated to uphold the law of the country, and the dispute over whether

the Crown had any right to arbitrary powers had been resolved by the English Civil

War of the 1640s, which had resulted in the execution of King Charles I. The

accession of King George III’s great-grandfather as George I showed the accep-

tance of the country for a constitutional monarch who would rule—as he did—

through ministers, with Robert Walpole being acknowledged as the first prime

minister in the modern sense of the word (although Walpole himself never

assumed that title).

However, in the colonies, the British government exercised its authority through

governors appointed by the prime minister, in consultation with the king, but who

acted in the name of the king. These were often British officials and friends or court-

iers of the king, and exclusiv ely drawn from the British ruling class. Howe v er, many

had close connections with the Americas. Indeed, John Wentworth, the governor of

New Hampshire during the Pine Tree Riot, was born in New Hampshire, as had

his uncle and predecessor Benning Wentworth. Wentworth was a popular governor

and did much to reduce possible tension between the government and the people in

New Hampshire, but others were not so accommodating. Thomas Hutchinson, the

governor of Massachusetts Bay from 1769 until 1774, had been born in Boston,

and was thoroughly immersed in Massachusetts politics. However, he wanted the

British to enforce more control over his colony, helping lead to the confrontation

with the Boston Tea Party. His successor, Thomas Gage, was bor n in England,

although he had served extensiv ely in North America.

—Justin Corfield

187

Further Reading

Harris, R. W. Political Ideas 1760–1792. London: Victor Gollancz, 1963.

Namier, Sir Lewis. England in the Age of the American Revolution. Lo ndon: Macmillan,

1961.

Shipbuilding

When William of Normandy (later William the Conqueror) prepared his invasion

fleet for England in 1066, it is known that tens of thousands of trees were cut down

for him to build his invasion fleet, many of the boats being burned after his land-

ing. Subsequent to that, many trees throu ghout England were cut down for build-

ing ships during the H undred Years’ Wa r, and in the reigns of Henry VIII and

Elizabeth I. The continual building of ships in Britain—both for the Royal Navy

and the merchant navy—resulted in the loss of so many large trees in the British

Isles t hat there were not enough long st raight logs to make masts for ships. The

strength of the mast became increasingly important with the improvement in naval

artillery, with cannonballs, linked with chain s, being fired at an enemy’s riggi ng

and masts.

During the 17th century, the British had mainly used fir trees for the masts, with

each mast being cut from a single tree. However, by the early 18th century, there

were not enough large fir trees for main masts, and because of the weight of sails,

it soon became necessary to make a mast out of a number of pieces of timber, often

causing masts to break under strain. As Britain, France, and Spain quickly used up

all suitable trees, mast ships brought wood from the Baltic, satisfying the demand

for a while. However the British were keen on their own supply of trees for masts.

With the increasing trans-Atlantic trade, a nd the availability of strong pine trees

from New England , it w as not long before the establishment of a number of

shipbuilding facilit ies in North America, most no tably at Newburyport in New

Hampshire. This led to timber being sourced in New Hampshire and then floated

down the Amoskeag River to Newburyport, where a shipbuilding industry

flourished as it also did in Massachusetts and Maine.

The industry involved not only large numbers of carpenters, but also sail mak-

ers, rope makers, and people to provision the ships. As much of the food on board

ships was kept in barrels and casks, coopers were always needed. The shipbuilding

industry resulted in an insatiable demand for wood, and naval architects kept hun-

dreds of carpenters busy sizing and sorting wood, sawing it into planks, and then

nailing these into place. Although the workforce could move to a new site, it was

the availability of nearby forests and woodland wi th large numbers of sizeable

188 Pine Tree Riot (1772)

trees that was most essential for any shipbuilding industry. This indeed explains

the l ocation of so many shipbuilding settlements including in Austral ia, w hich

was able to source Norfolk Island pine trees from Norfolk Island, in the Pacific.

Certainly the overall design of ships and the nature of making them changed little

from the late 16th to the early 19th c enturies, with the major changes being the

ships becoming larger, and having to be fashioned out of smaller and smaller

planks of wood.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Morrison, John S. Aspects of the History of Wooden Shipbuilding. London: National

Maritime Museum, 1970.

Pollock, David. The Shipbuilding Industry: Its His tory, P ractice, Scien ce and Finance.

London: Methuen & Co., 1905.

Pine Tree Riot (1772) 189

Boston Tea Party (1773)

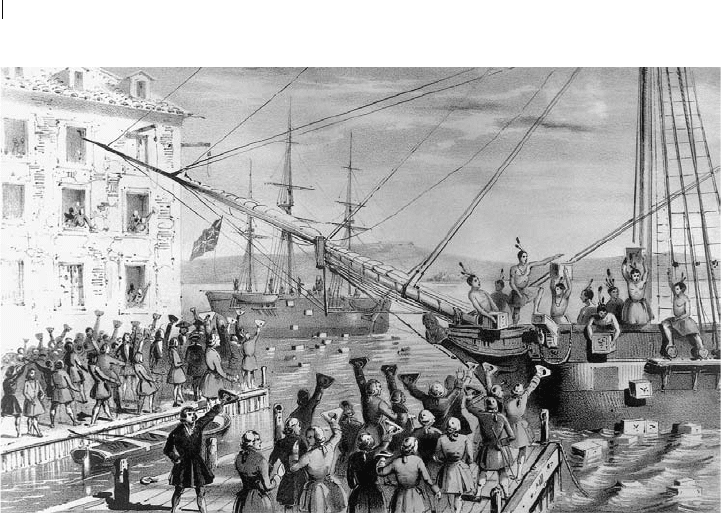

Few incidents in Ame rican history are as well known as the Boston Tea Party. It

brings to mind images of colonists dressed as Indians , carrying tomahawks a nd

calling war whoops while traipsing t hough the cold December air to Griffin’s

Wharf. However, there is a reason why the Bost on Tea Party is a staple in every

American history textbook. It marks the turning point between the American col-

onists and the British government. It helped to deepen the divide among the patri-

ots and the loyalists. And it brought the colonies one step closer to independence.

To understand how the Boston Tea Party came about, one must look back to the

Seven Years’ War between the British and the French over the territory of Quebec.

For as long as the British had been settled in the “New World” of what is now New

England, they had to worry about French forces to their north and west in what is

now Quebec, Canada. From 1754 until 1763, the British and French fought over

the territory, with Britain finally declaring victory and driving the French out once

and for all. Despite a victory and a great deal of new territory gained following the

Seven Years’ War, Great Britain found itself mired in debt. Plus, they needed to

maintain 10,000 soldiers in the col onies, in case the French tried to take Quebec

back by force.

In an effort toward fiscal improvement, Parliament looked for new ways to tax

its colonies. During the Seven Years’ War, British officials saw closely just how

prosperous many American colonists w ere. There were tidy farms, and neat vil-

lages with bustling shops and tradesmen. Compared to the intolerable living con-

ditions back in Great Britain, the American colonists were doing remarkably

well for themselves. British authorities also saw how many colonists ignored laws

concerning trade and taxes. Many merchants openly flaunted the laws, not paying

taxes or duties on goods. Because there was a high turnover rate of British officials

in the colonies, it was hard to maintain an effective policy, making it easy for col-

onists to do as they pleased.

To this end, the British Parliament reasoned that since so much bloodshed and

money had been spent securing the American continent from the French, the col-

onists should pay their fair share. In co mparison to the average British citizen,

who paid 26 shillings a year in taxes, colonists paid an average of one shilling

per year in taxes. Plus, living conditions in Great Britain were squalid with little

hope of improvement, while in the American colonies, there was always the hope

191

to own your own land and work your own farm. So it seemed completely reason-

able to Great Britain that the American colonists pay their share in taxes. After

all, they the colonists were doing remarkably well, carving prosperous farms out

of the vast wilderness. However, the colonists did not agree. With the French

removed from Quebec, the American colonists and British no longer had a

common enemy to unite them. The colonists did not feel the need for British

soldiers to be stationed in the colonies to protect them. They could take care of

themselves, they declared.

In an effort to raise much-ne eded revenue, Parliament passed the Townshend

Act in 1767. The act placed new taxes on goods imported from Great Britain, such

as tea, paper, lead, and glass. The Townshend Act also used taxes to pay the sala-

ries of certain royal officials in the colonies, removing a considerable amount of

leverage from the colonial assemblies, which could withhold official’s salaries if

they did not like their actions. The Townshend Act was almost immediately

repealed, as colonists boycotted English goods. However, the tax on tea remained.

Tea had been imported into the American colonies with regularity, starting in

the 17 20s. By the passage of the Townshend Act, c olonists consumed roughly

1.2 million pounds of tea a year. Tea was not just a beverage; it was an important

thread of colonial society. While it was most associated with the women of the

upper class, tea parties were social occasions for both men and women, when

192 Boston Tea Party (1773)

Bostonians, dressed as Mohawk Indians, throwing East India Company tea into the harbor in

December 1773. (National Archives and Records Administration)

people took a break from the handwork of everyday life to visit with neighbors and

friends. Families displayed their precious china or silver tea services, which was a

distinct sign of wealth and prestige. The remaining tax on tea, left over from the

Townshend Act, made English tea exp ensive, and soon colon ists began drinking

smuggled tea from the Netherlands instead. Because there w ere not enoug h cus-

toms officials to effectively patrol the American coastline, it was easy to smuggle

in tea (and other goods) in the many inlets that were hidden along the rocky shores.

Although the bo ycott s temming from the Townshend Act was strong in 1770, by

1773 it had begun to wane. Many people resumed drinking tea, some in private,

others in the open. But the bo ycott had its intended result. Sales of British tea,

especially from the East India Company, dropped drastically.

By May 1773, the market for colonial tea had collapsed, and the East India

Company was on the verge of collapse. There was a grea t deal of vested interest

in the East I ndia Company. Many members of the British Parliament held shares

in the shipping company. More importantly, the East India Company was the sole

British agent in India. Parliament could not afford for the company to go bankrupt.

So they passed the Tea Act, which placed special duties on tea. In Boston, East

India tea could be sold only by seven designated tea agents, called consignees. It

was no coincidence that all seven consignees were Loyalists. Many of them were

related to the royal governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson. The Tea Act

allowed the East India Company to skirt any middlemen and undersell their com-

petitors, even cheaper smuggled Dutch tea. Parliament reasoned that A merican

colonists would gladly pay a small three-pence tax, to buy such cheap tea. It would

be a win-win situation for everyone: the colonists would have their tea, the East

India Company would stay in business, and the Crown would have some money

in the treasury. However, many American colonists did carry this same view.

Many patriots who had helped repeal the Townshend Act, the Stamp Act, and

other unwanted taxes saw the new tax on tea as Parliament’s way of exercising

their right to tax the colonists without representation. Others saw the Tea Act as

the first step toward domination of the marketplace by the East India Company.

All in all, the Tea Act was a violation of colonists’ freedom and liberty. It was

okay to pay the taxes levied by local assemblies, but Parliament, an alien body

far removed from the col onists, had no right to tell them what to do. The Sons of

Lib erty, who had remained quiet for the past several years, sprang into action to

protest the Tea Act. This time, they were joined by the normally conservative mer-

chant class, whose profits were endangered by the act.

American-British relati ons were not helped when s ecret letters from the royal

governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson to British undersecretary Thomas

Whatley, were published in the colonies. In h is letters, Hutchinson called for

sterner measures of discipline for the colonists. He specifically called for “an

Boston Tea Party (1773) 193