Charles M. Kozierok The TCP-IP Guide

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 621 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

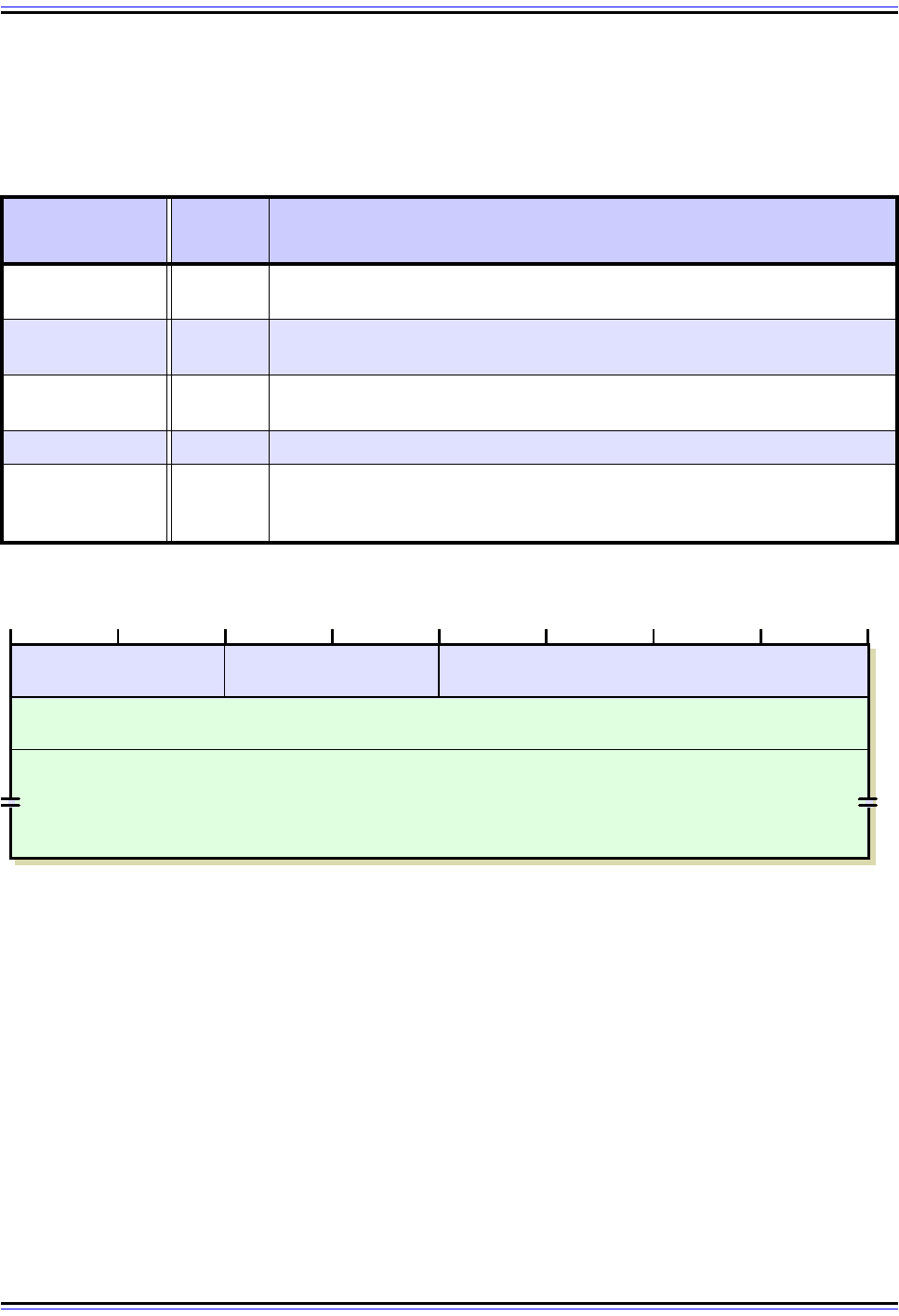

ICMPv4 Destination Unreachable Message Format

Table 89 and Figure 139 show the specific format for ICMPv4 Destination Unreachable

messages.

ICMPv4 Destination Unreachable Message Subtypes

There are many different reasons why it may not be possible for a datagram to reach its

destination. Some of these may be due to erroneous parameters (like the invalid IP address

example mentioned above.) A router might have a problem reaching a particular network

for whatever reason. There can also be other more “esoteric” reasons as well why a

datagram cannot be delivered.

Table 89: ICMPv4 Destination Unreachable Message Format

Field Name

Size

(bytes)

Description

Type 1

Type: Identifies the ICMP message type; for Destination Unreachable

messages this is set to 3.

Code 1

Code: Identifies the “subtype” of unreachable error being communicated.

See Table 90 for a full list of codes and what they mean.

Checksum 2

Checksum: 16-bit checksum field for the ICMP header, as described in the

topic on the ICMP common message format.

Unused 4 Unused: 4 bytes that are left blank and not used.

Original

Datagram

Portion

Variable

Original Datagram Portion: The full IP header and the first 8 bytes of the

payload of the datagram that prompted this error message to be sent.

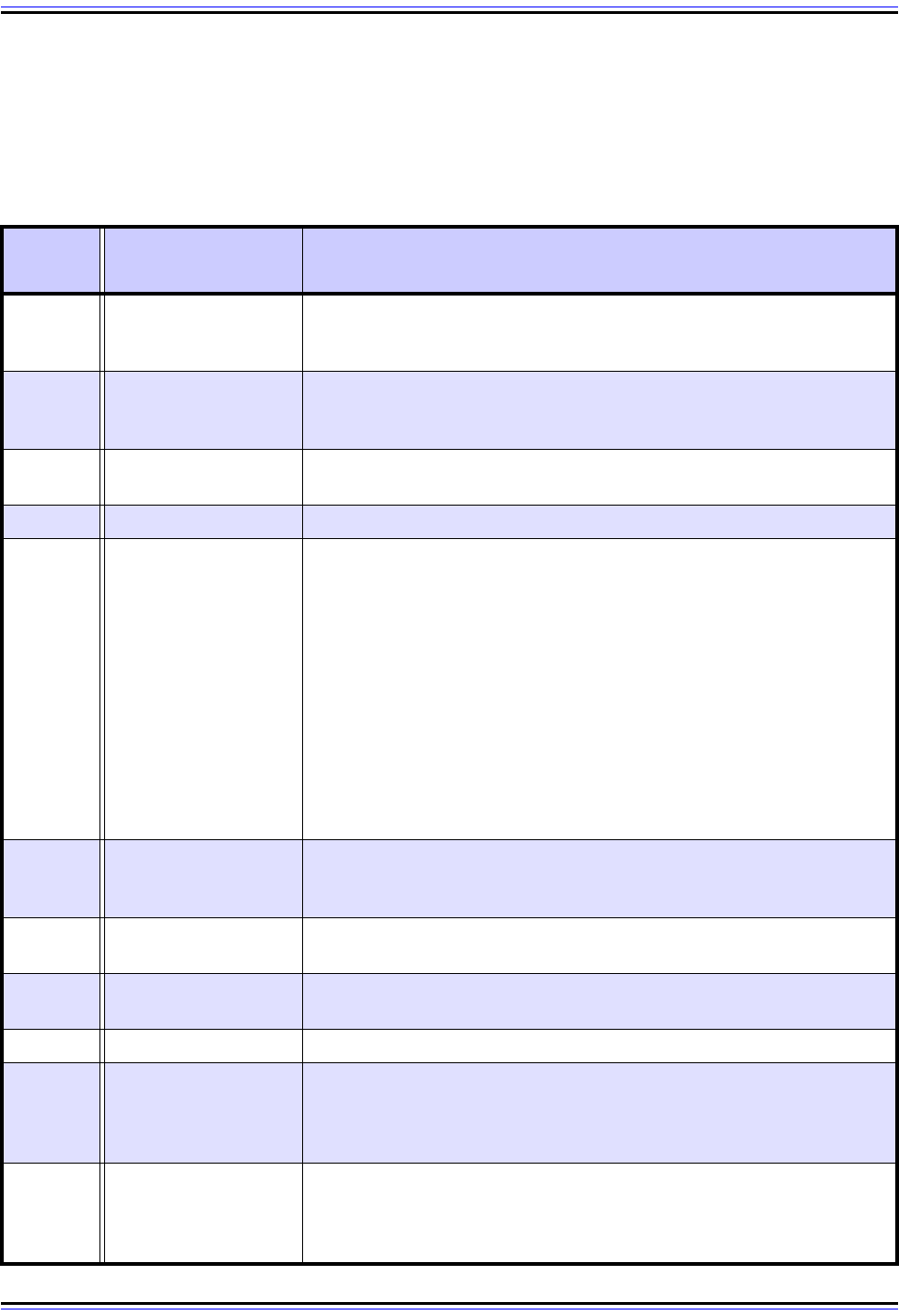

Figure 139: ICMPv4 Destination Unreachable Message Format

Type = 3

Code

(Error Subtype)

Checksum

Unused

Original IP Datagram Portion

(Original IP Header + First Eight Bytes Of Data Field)

4 8 12 16 20 24 28 320

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 622 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

For this reason, the ICMPv4 Destination Unreachable message type can really be

considered a class of related error messages. The receipt of a Destination Unreachable

message tells a device that the datagram it sent couldn't be delivered, and the reason for

the non-delivery is indicated by the Code field in the ICMP header. Table 90 shows the

different Code values, corresponding message subtypes and a brief explanation of each.

Table 90: ICMPv4 Destination Unreachable Message Subtypes (Page 1 of 2)

Code

Value

Message Subtype Description

0

Network

Unreachable

The datagram could not be delivered to the network specified in the

network ID portion of the IP address. Usually means a problem with

routing but could also be caused by a bad address.

1 Host Unreachable

The datagram was delivered to the network specified in the network ID

portion of the IP address but could not be sent to the specific host

indicated in the address. Again, this usually implies a routing issue.

2

Protocol

Unreachable

The protocol specified in the Protocol field was invalid for the host to

which the datagram was delivered.

3 Port Unreachable The destination port specified in the UDP or TCP header was invalid.

4

Fragmentation

Needed and DF Set

This is one of those “esoteric” codes. ☺ Normally, an IPv4 router will

automatically fragment a datagram that it receives if it is too large for

the maximum transmission unit (MTU) of the next physical network link

the datagram needs to traverse. However, if the DF (Don't Fragment)

flag is set in the IP header, this means the sender of the datagram

does not want the datagram ever to be fragmented. This puts the

router between the proverbial rock and hard place, and it will be forced

to drop the datagram and send an error message with this code.

This message type is most often used in a “clever” way, by intentionally

sending messages of increasing size to discover the maximum trans-

mission size that a link can handle. This process is called MTU path

discovery.

5 Source Route Failed

Generated if a source route was specified for the datagram in an option

but a router could not forward the datagram to the next step in the

route.

6

Destination Network

Unknown

Not used; Code 0 is used instead.

7

Destination Host

Unknown

The host specified is not known. This is usually generated by a router

local to the destination host and usually means a bad address.

8 Source Host Isolated Obsolete, no longer used.

9

Communication with

Destination Network

is Administratively

Prohibited

The source device is not allowed to send to the network where the

destination device is located.

10

Communication with

Destination Host is

Administratively

Prohibited

The source device is allowed to send to the network where the desti-

nation device is located, but not that particular device.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 623 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

As you can see in that table, not all of these codes are actively used at this time. For

example, code 8 is obsolete and code 0 is used instead of 6. Also, some of the higher

numbers related to the Type Of Service field aren't actively used because Type Of Service

isn't actively used.

Key Concept: ICMPv4 Destination Unreachable messages are used to inform a

sending device of a failure to deliver an IP datagram. The message’s Code field

provides information about the nature of the delivery problem.

Interpretation of Destination Unreachable Messages

Finally, it's important to remember that just as IP is “best effort”, the reporting of

unreachable destinations using ICMP is also “best effort”. For one things, these ICMP

messages are themselves carried in IP datagrams. More than that, however, one must

remember that there may be problems that prevent a router from detecting failure of

delivery of an ICMP message, such as a low-level hardware problem. A router could,

theoretically, also be precluded from sending an ICMP message even when failure of

delivery is detected, for whatever reason.

For this reason, the sending of Destination Unreachable messages should be considered

supplemental. There is no guarantee that every problem sending a datagram will result in

a corresponding ICMP message. No device should count on receiving an ICMP Destination

Unreachable for a failed delivery any more than it counts on the delivery in the first place.

This is why the higher-layer mechanisms mentioned at the start of this topic are still

important.

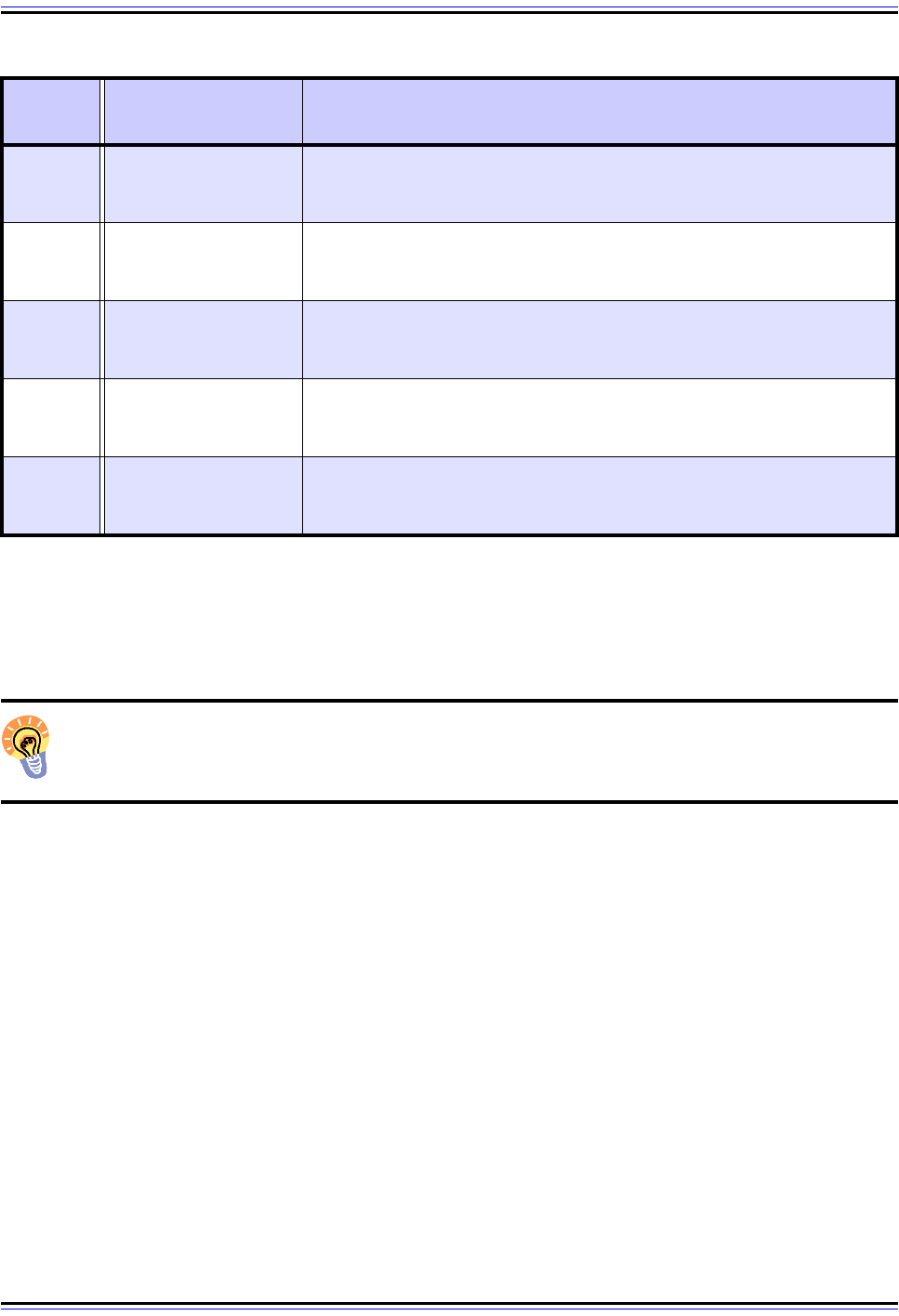

11

Destination Network

Unreachable for

Type of Service

The network specified in the IP address cannot be reached due to

inability to provide service specified in the Type Of Service field of the

datagram header.

12

Destination Host

Unreachable for

Type of Service

The destination host specified in the IP address cannot be reached

due to inability to provide service specified in the datagram's Type Of

Service field.

13

Communication

Administratively

Prohibited

The datagram could not be forwarded due to filtering that blocks the

message based on its contents.

14

Host Precedence

Violation

Sent by a first-hop router (the first router to handle a sent datagram)

when the Precedence value in the Type Of Service field is not

permitted.

15

Precedence Cutoff In

Effect

Sent by a router when receiving a datagram whose Precedence value

(priority) is lower than the minimum allowed for the network at that

time.

Table 90: ICMPv4 Destination Unreachable Message Subtypes (Page 2 of 2)

Code

Value

Message Subtype Description

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 624 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

ICMPv4 Source Quench Messages

When a source device sends out a datagram, it will travel across the internetwork and

eventually arrive at its intended destination—hopefully. At that point, it is up to the desti-

nation device to process the datagram, by examining it and determining which higher-layer

software process to hand the datagram.

If a destination device is receiving datagrams at a relatively slow rate, it may be able to

process each datagram “on the fly” as it is received. However, datagram receipt in a typical

internetwork can tend to be uneven or “bursty”, with alternating higher and lower rates of

traffic. To allow for times when datagrams are arriving faster than they can be processed,

each device has a buffer where it can temporarily hold datagrams it has received until it has

a chance to deal with them.

However, this buffer is itself limited in size. Assuming the device has been properly

designed, the buffer may be sufficient to smooth out high-traffic and low-traffic periods most

of the time. Certain situations can still arise in which traffic is received so rapidly that the

buffer itself fills up entirely. Some examples of scenarios in which this might happen include:

☯ A single destination is overwhelmed by datagrams from many sources, such as a

popular Web site being swamped by HTTP requests.

☯ Device A and device B are exchanging information but device A is a much faster

computer than device B and can generate outgoing and process incoming datagrams

much faster than B can.

☯ A router receives a large number of datagrams over a high-speed link that it needs to

forward over a low-speed link; they start to pile up while waiting to be sent over the

slow link.

☯ A hardware failure or other situation causes datagrams to sit at a device unprocessed.

A device that continues to receive datagrams when it has no more buffer space is forced to

discard them, and is said to be congested. A source that has its datagram discarded due to

congestion won't have any way of knowing this, since IP itself is unreliable and unacknowl-

edged. Therefore, while it is possible to simply allow higher-layer protocols to detect the

dropped datagrams and generate replacements, it makes a lot more sense to have the

congested device provide feedback to the sources, telling them that it is overloaded.

In IPv4, a device that is forced to drop datagrams due to congestion provides feedback to

the sources that overwhelmed it by sending them ICMPv4 Source Quench messages. Just

as we use water to quench a fire, a Source Quench method is a signal that attempts to

quench a source device that is sending too fast. In other words, it's a polite way for one IP

device to tell another: “SLOW DOWN!” When a device receives one of these messages it

knows it needs to cut down on how fast it is sending datagrams to the device that sent it.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 625 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

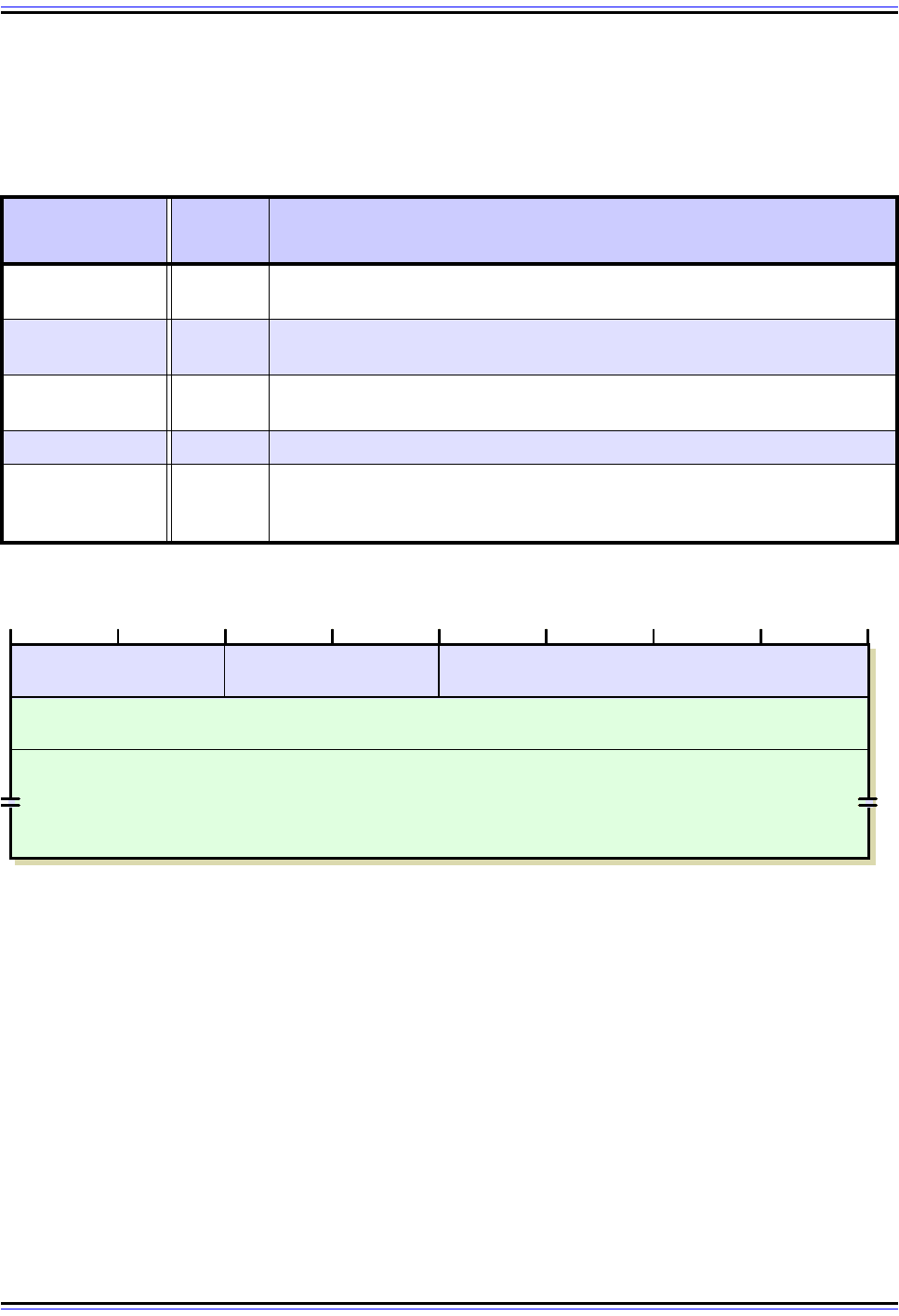

ICMPv4 Source Quench Message Format

The specific format for ICMPv4 Source Quench messages can be found in Table 91 and

Figure 140.

Problems With Source Quench Messages

What's interesting about the Source Quench format is that it is basically a “null message”. It

tells the source that the destination is congested but provides no specific information about

that situation, nor does it specify what exactly the destination wants the source to do, other

than to cut back on its transmission rate in some way. There is also no method for the desti-

nation to signal a source it has “quenched” that it is no longer congested and to resume its

prior sending rate. This means the response to a Source Quench is left up to the device that

receives it. Usually, a device will cut back its transmission rate until it no longer receives the

messages any more, and then may try to slowly increase the rate again.

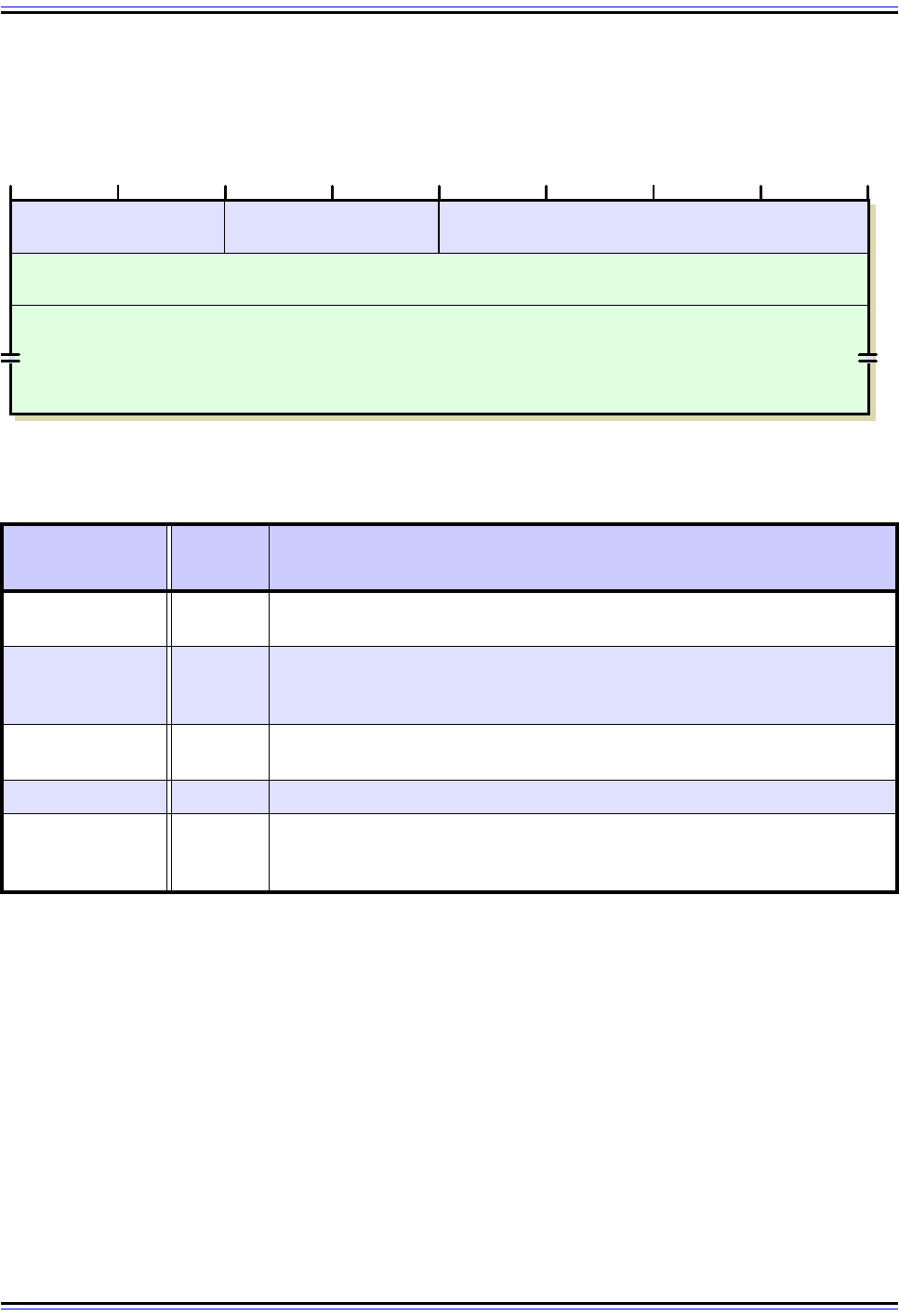

Table 91: ICMPv4 Source Quench Message Format

Field Name

Size

(bytes)

Description

Type 1

Type: Identifies the ICMP message type; for Source Quench messages

this is set to 4.

Code 1

Code: Identifies the “subtype” of error being communicated. For Source

Quench messages this is not used, and the field is set to 0.

Checksum 2

Checksum: 16-bit checksum field for the ICMP header, as described in the

topic on the ICMP common message format.

Unused 4 Unused: 4 bytes that are left blank and not used.

Original

Datagram

Portion

Variable

Original Datagram Portion: The full IP header and the first 8 bytes of the

payload of the datagram that was dropped due to congestion.

Figure 140: ICMPv4 Source Quench Message Format

Type = 4 Code = 0 Checksum

Unused

Original IP Datagram Portion

(Original IP Header + First Eight Bytes Of Data Field)

4 8 12 16 20 24 28 320

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 626 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

In a similar manner, there are no rules about when and how a device generates Source

Quench messages in the first place. A common convention is that one message is

generated for each dropped datagram. However, more intelligent algorithms may be

employed, specially on higher-end routers, to predict when the device's buffer will be filled

and preemptively quench certain sources that are sending too quickly. Devices may also

decide whether to quench all sources when they become busy, or only certain ones. As with

other ICMP error messages, a device cannot count on a Source Quench being sent when

one of its datagrams is discarded by a busy device.

The lack of information communicated in Source Quench messages makes them a rather

crude tool for managing congestion. In general terms, the process of regulating the sending

of messages between two devices is called flow control, and is usually a function of the

transport layer. The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) actually has a flow control

mechanism that is far superior to the use of ICMP Source Quench messages.

Another issue with Source Quench messages is that they can be abused. Transmission of

these messages by a malicious user can cause a host to be slowed down when there is no

valid reason. This security issue, combined with the superiority of the TCP method for flow

control, has caused Source Quench messages to largely fall out of favor.

Key Concept: ICMPv4 Source Quench messages are sent by a device to request

that another reduce the rate at which it is sending datagrams. They are a rather

crude method of flow control compared to more capable mechanisms such as that

provided by TCP.

ICMPv4 Time Exceeded Messages

Large IP internetworks can have thousands of interconnected routers that pass datagrams

between devices on various networks. In large internetworks, the topology of connections

between routes can become complex, which makes routing more difficult. Routing protocols

will normally allow routers to find the best routes between networks, but in some situations

an inefficient route might be selected for a datagram.

In the worst case of inefficient routing, a router loop may occur. An example of this situation

is where Router A thinks datagrams intended for network X should next go to Router B;

Router B thinks they should go to Router C; and Router C thinks they need to go to Router

A. (See the ICMPv6 TIme Exceeded Message description for an illustration of a router

loop.)

If a loop like this occurred, datagrams for network X entering this part of the internet would

circle forever, chewing up bandwidth and eventually leading to the network being unusable.

As insurance against this occurrence, each IP datagram includes in its header a Time To

Live (TTL) field. This field was originally intended to limit the maximum time (in seconds)

that a datagram could be on the internetwork, but now limits the life of a datagram by

limiting the number of times the datagram can be passed from one device to the next. The

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 627 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

TTL is set to a value by the source that represents the maximum number of hops it wants

for the datagram. Each router decrements the value; if it ever reaches zero the datagram is

said to have expired and is discarded.

When a datagram is dropped due to expiration of the TTL field, the device that dropped the

datagram will inform the source of this occurrence by sending it an ICMPv4 Time Exceeded

message, as shown in Figure 141. Receipt of this message indicates to the original sending

device that there is either a routing problem when sending to that particular destination, or

that it set the TTL field value too low in the first place. As with all ICMP messages, the

device receiving it must decide whether and how to respond to receipt of the message. For

example, it may first try to re-send the datagram with a higher TTL value.

There is another “time expiration” situation where ICMP Time Exceeded messages are

used. When an IP message is broken into fragments, the destination device is charged with

reassembling them into the original message. One or more fragments may not make it to

the destination, so to prevent the device from waiting forever, it sets a timer when the first

fragment arrives. If this timer expires before the others are received, the device gives up on

this message. The fragments are discarded, and a Time Exceeded message generated.

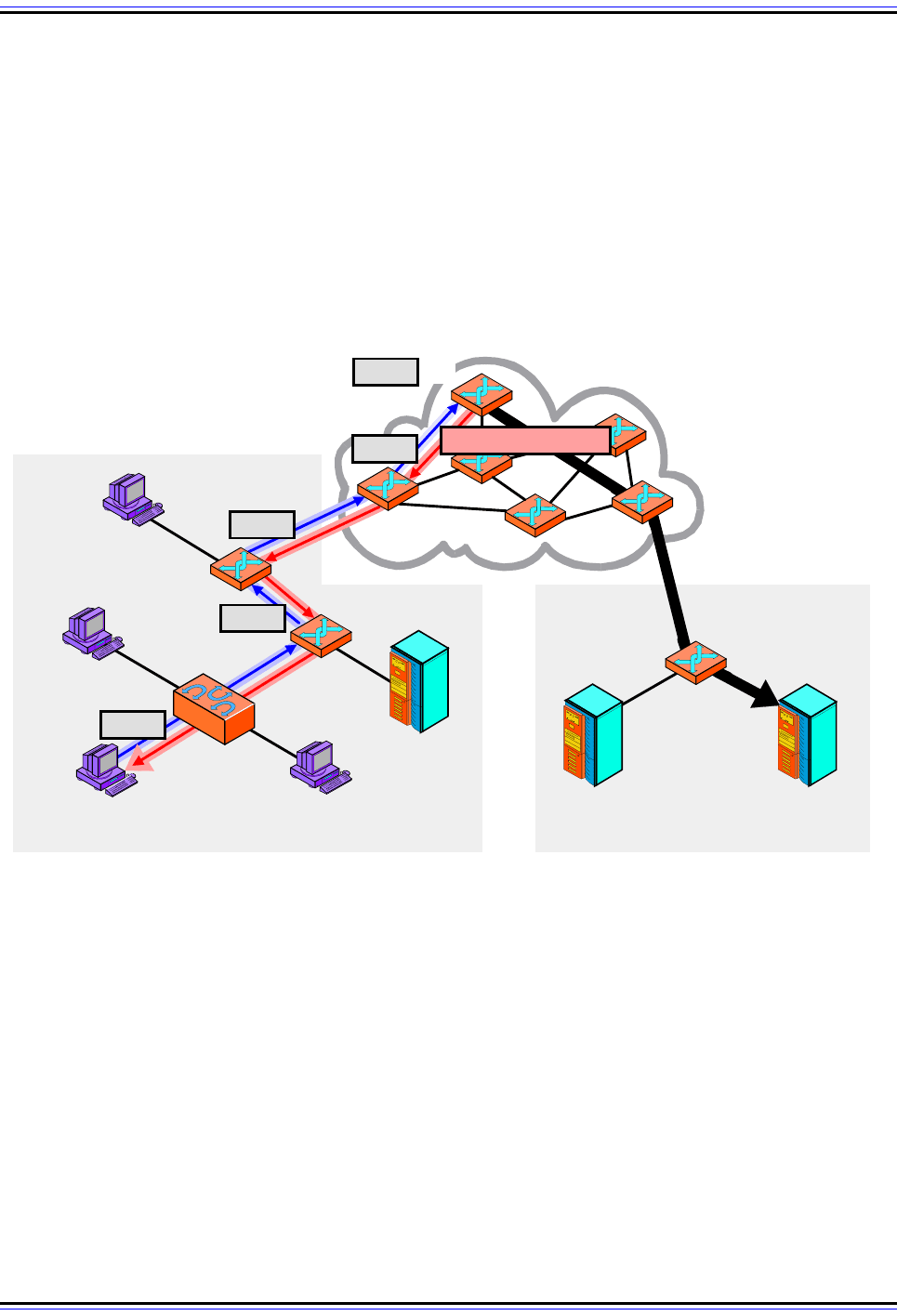

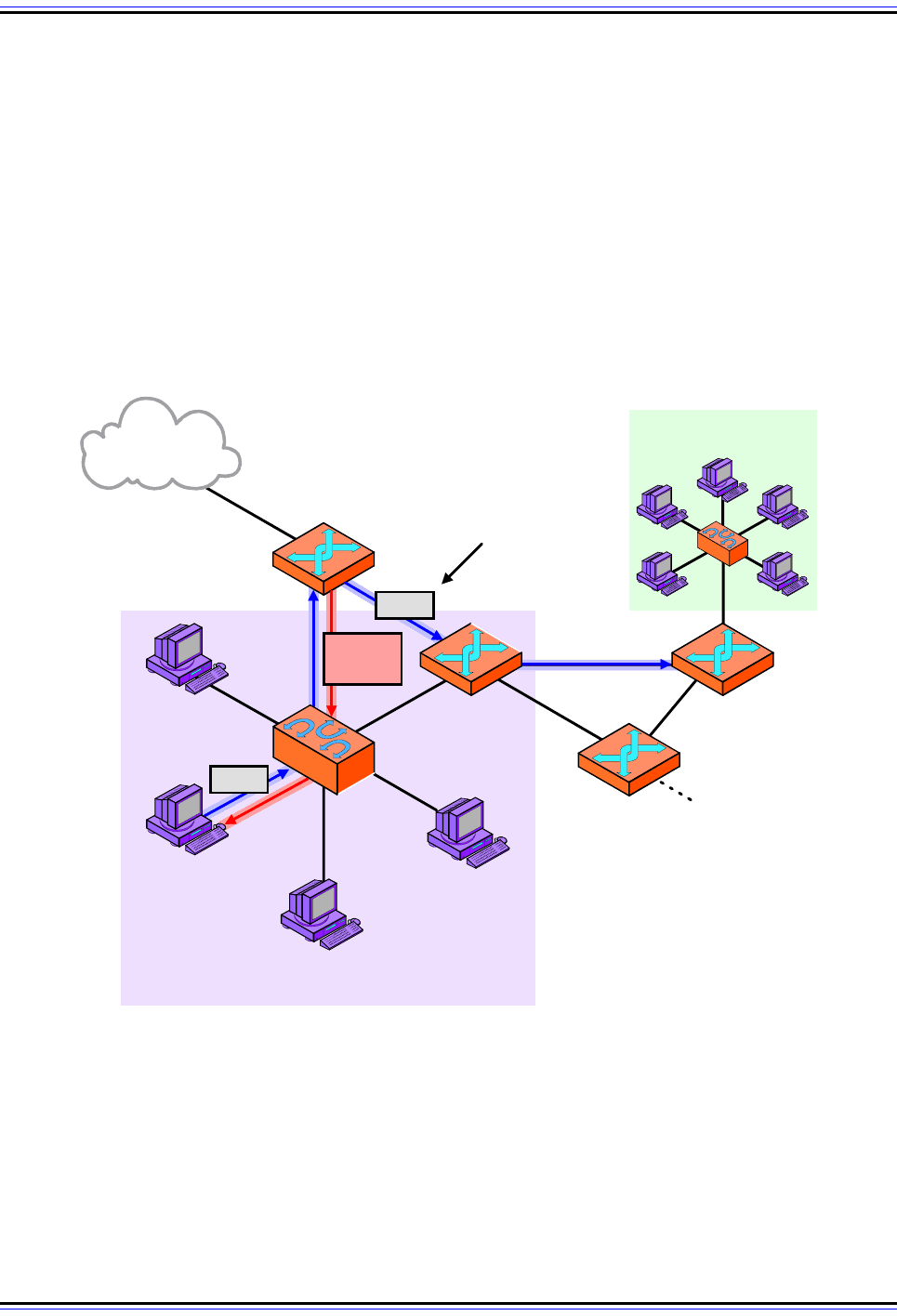

Figure 141: Expiration of an IP Datagram and Time Exceeded Message Generation

In this example, device A sends an IP datagram to device B that has a Time To Live (TTL) field value of only 4

(perhaps not realizing that B is 7 hops away). On the fourth hop the datagram reaches R4, which decrements

its TTL field to zero and then drops it as expired. R4 then sends an ICMP Time Exceeded message back to A.

B

R1

R2

A

Remote NetworkLocal Network

R3

R4

R5

R6

TTL = 1

ICMP Time Exceeded

TTL = 2

TTL = 3

TTL = 4

TTL = 0

Internet

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 628 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

ICMPv4 Time Exceeded Message Format

Table 92 and Figure 142 show the specific format for ICMPv4 Time Exceeded messages.

Applications of Time Exceeded Messages

As an ICMP error message type, ICMP Time Exceeded messages are usually sent in

response to the two conditions described above (TTL or reassembly timer expiration).

Generally, Time To Live expiration messages are generated by routers as they try to route a

datagram, while reassembly violations are indicated by end hosts. However, there is

actually a very clever application of these messages that has nothing to do with reporting

errors at all.

Figure 142: ICMPv4 Time Exceeded Message Format

Table 92: ICMPv4 Time Exceeded Message Format

Field Name

Size

(bytes)

Description

Type 1

Type: Identifies the ICMP message type; for Time Exceeded messages

this is set to 11.

Code 1

Code: Identifies the “subtype” of error being communicated. A value of 0

indicates expiration of the IP Time To Live field; a value of 1 indicates that

the fragment reassembly time has been exceeded.

Checksum 2

Checksum: 16-bit checksum field for the ICMP header, as described in the

topic on the ICMP common message format.

Unused 4 Unused: 4 bytes that are left blank and not used.

Original

Datagram

Portion

Variable

Original Datagram Portion: The full IP header and the first 8 bytes of the

payload of the datagram that was dropped due to expiration of the TTL field

or reassembly timer.

Type = 11

Code

(Timer Type)

Checksum

Unused

Original IP Datagram Portion

(Original IP Header + First Eight Bytes Of Data Field)

4 8 12 16 20 24 28 320

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 629 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Key Concept: ICMPv4 Time Exceeded messages are sent in two different “time-

related” circumstances. The first is if a datagram’s Time To Live (TTL) field is

reduced to zero, causing it to expire and the datagram to be dropped. The second is

when all the pieces of a fragmented message are not received before the expiration of the

recipient’s reassembly timer.

The TCP/IP traceroute (or tracert) utility is used to show the sequence of devices over

which a datagram is passed on a particular route between a source and destination, as well

as the amount of time it takes for a datagram to reach each hop in that route. This utility was

originally implemented using Time Exceeded messages by sending datagrams with

successively higher TTL values. First, a “dummy” datagram is sent with a TTL value of 1,

causing the first hop in the route to discard the datagram and send back an ICMP Time

Exceeded; the time elapsed for this could be measured. Then, a second datagram is sent

with a TTL value of 2, causing the second device in the route to report back a Time

Exceeded, and so on. By continuing to increase the TTL value we can get reports back

from each hop in the route. See the topic describing traceroute for more details on its

operation.

ICMPv4 Redirect Messages

Every device on an internetwork needs to be able to send to every other device. If hosts

were responsible for determining the routes to each possible destination, each host would

need to maintain an extensive set of routing information. Since there are so many hosts on

an internetwork, this would be a very time-consuming and maintenance-intensive situation.

Instead, IP internetworks are designed around a fundamental design decision: routers are

responsible for determining routes and maintaining routing information. Hosts only

determine when they need a datagram routed, and then hand the datagram off to a local

router to be sent where it needs to go. I discuss this in more detail in my overview of IP

routing concepts.

Since most hosts do not maintain routing information, they must rely on routers to know

about routes and where to send datagrams intended for different destinations. Typically, a

host on an IP network will start out with a routing table that basically tells it to send every-

thing not on the local network to a single default router, which will then figure out what to do

with it. Obviously if there is only one router on the network, the host will use that as the

default router for all non-local traffic. However, if there are two or more routers, sending all

datagrams to just one router may not make sense. It is possible that a host could be

manually configured to know which router to use for which destinations, but another

mechanism in IP can allow a host to learn this automatically.

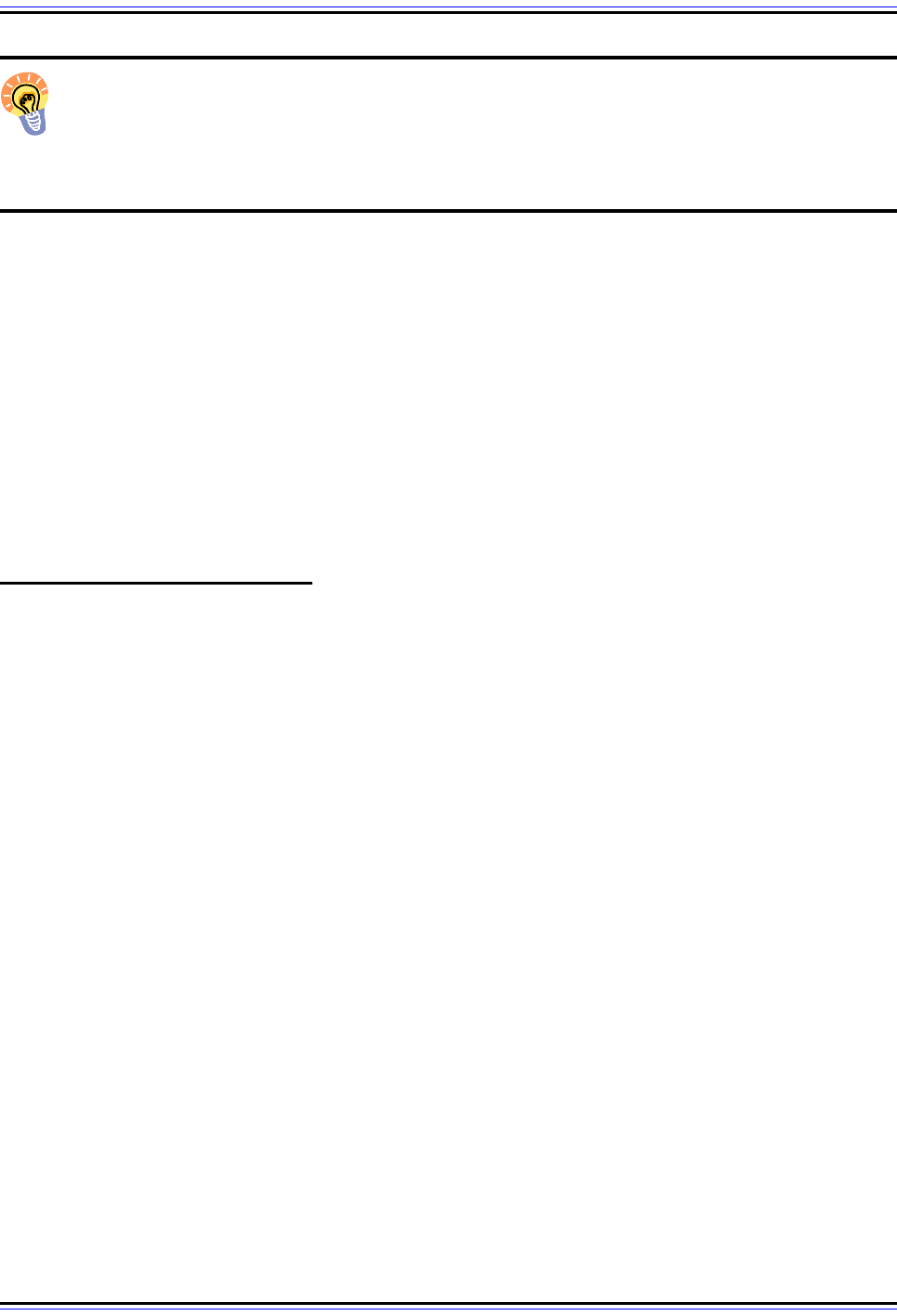

Consider a network N1 that contains a number of hosts (H1, H2, etc…) and two routers, R1

and R2. Host H1 has been configured to send all datagrams to R1, as its default router.

Suppose it wants to send a datagram to a device on a different network (N2). However, N2

is most directly connected to N1 using R2 and not R1. The datagram will first be sent to R1.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 630 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

R1 will look in its routing table and see that datagrams for N2 need to be sent through R2.

“But wait,” R1 says. “R2 is on the local network, and H1 is on the local network—so why am

I needed as a middleman? H1 should just send datagrams for N2 directly to R2 and leave

me out of it.

In this situation, R1 will send an ICMPv4 Redirect message back to H1, telling it that in the

future it should send this type of datagram directly to R2. This is shown in Figure 143. R1

will of course also forward the datagram to R2 for delivery, since there is no reason to drop

the datagram. Thus, despite usually being grouped along with true ICMP error messages,

Redirect messages are really arguably not error messages at all; they represent a situation

only where an inefficiency exists, not an outright error. (In fact, in ICMPv6 they have been

reclassified.)

Figure 143: Host Redirection Using an ICMP Redirect Message

In this example H1 sends to R1 a datagram destined for network N2. However, R1 notices that R2 is on the

same network and is a more direct route to N2. It forwards the datagram on to R2 but also sends an ICMP

Redirect message back to H1 to tell it to use R2 next time.

R2

Network N1

R1

Internet

R3

Network N2

H1

ICMP

Re dir e ct

IP

IP

Datagram Delivery

Continues

R4