Charles M. Kozierok The TCP-IP Guide

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 571 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

The ISAKMP security association negotiated during Phase 1 includes the negotiation of the

following attributes used for subsequent negotiations:

☯ An encryption algorithm to be used, such as the Data Encryption Standard (DES).

☯ A hash algorithm (MD5 or SHA, as used by AH or ESP).

☯ An authentication method, such as authentication using previously shared keys.

☯ A Diffie-Hellman group. Diffie and Hellman were two pioneers in the industry who

invented public-key cryptography. In this method, instead of encrypting and decrypting

with the same key, data is encrypted using a public key knowable to anyone, and

decrypted using a private key that is kept secret. A Diffie-Hellman group defines the

attributes of how to perform this type of cryptography. Four predefined groups derived

from OAKLEY are specified in IKE and provision is allowed for defining new groups as

well.

Note that even though security associations in general are unidirectional, the ISAKMP SA is

established bidirectionally. Once Phase 1 is complete, then, either device can set up a

subsequent SA for AH or ESP using it.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 572 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Internet Protocol Mobility Support (Mobile IP)

The Internet Protocol (IP) is the most successful network layer protocol in computing due to

its many strengths, but it also has some weaknesses, most of which have become more

important as networks have evolved over time. Technologies like classless addressing and

Network Address Translation combat the exhaustion of the IPv4 address space, while

IPSec provides it with secure communications it lacks. Another weakness of IP is that it was

not designed with mobile computers in mind.

While mobile devices can certainly use IP, the way that devices are addressed and

datagrams routed causes a problem when they are moved from one network to another. At

the time IP was developed, computers were large and rarely moved. Today, we have

millions of notebook computers and smaller devices, some of which even use wireless

networking to connect to the wired network. The importance of providing full IP capabilities

for these mobile devices has grown dramatically. To support IP in a mobile environment, a

new protocol called IP Mobility Support, or more simply, Mobile IP, was developed.

In this section I describe the special protocol developed to overcome the problems with

mobile computers attaching to IP internetworks. I begin with an overview of Mobile IP and a

more detailed description of why it was created. I discuss important concepts that define

Mobile IP and its general mode of operation. I then move on to some of the specifics of how

Mobile IP works. This includes a description of the special mobile IP addressing scheme,

an explanation of how agents are discovered by mobile devices, the process of registration

with the device's home agent, and how data is encapsulated and routed. I discuss the

impact that Mobile IP has on the operation of the TCP/IP Address Resolution Protocol

(ARP). I end the section by examining some of the efficiency and security issues that come

into play when Mobile IP is used.

Note: This section describes specifically how IP mobility support is provided for

IPv4 networks. In the future I may add more specific details for how mobility is

implemented in IPv6.

Background Information: If you are not familiar with the basics of IP addressing

and routing, I strongly suggest at least skimming those sections before attempting

to read about Mobile IP.

Mobile IP Overview, History and Motivation

Mobile computing has greatly increased in popularity over the past several years, due

largely to advances in miniaturization. Today we can get in a notebook PC or even a hand-

held computer the power that once required a hulking behemoth of a machine. We also

have wireless LAN technologies that easily let a device move from place to place and retain

networking connectivity at the data link layer. Unfortunately, the Internet Protocol was

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 573 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

developed back in the era of the behemoths, and isn't designed to deal gracefully with

computers that move around. To understand why IP doesn't work well in a mobile

environment, we must take a look back at how IP addressing and routing function.

The Problem With Mobile Nodes in TCP/IP

If you've read any of the materials in this Guide on IP addressing—and I certainly hope that

you have—you know that IP addresses are fundamentally divided into two portions: a

network identifier (network ID) and a host identifier (host ID). The network ID specifies

which network a host is on, and the host ID uniquely specifies hosts within a network. This

structure is fundamental to datagram routing, because devices use the network ID portion

of the destination address of a datagram to determine if the recipient is on a local network

or a remote one, and routers use it to determine how to route the datagram.

This is a great system, but it has one critical flaw: the IP address is tied tightly to the

network where the device is located. Most devices never (or at least rarely) change their

attachment point to the network, so this is not a problem, but it is certainly an issue for a

mobile device. When the mobile device travels away from its home location, the system of

routing based on IP address “breaks”. This is illustrated in Figure 127.

Difficulties with Older Mobile Node Solutions

The tight binding of network identifier and host IP address means that there are only two

real options under conventional IP when a mobile device moves from one network to

another:

☯ Change IP Address: We can change the IP address of the host to a new address that

includes the network ID of the network to which it is moving.

☯ Decouple IP Routing From Address: We can change the way routing is done for the

device, so that instead of routers sending datagrams to it based on its network ID, they

route based on its entire address.

These both seem like viable options at first glance, and if only a few devices tried them they

might work. Unfortunately, they are both inefficient, often impractical, and neither is

scalable, meaning, practical when thousands or millions of devices try them:

☯ Changing the IP address each time a device moves is time-consuming and normally

requires manual intervention. In addition, the entire TCP/IP stack would need to be

restarted, breaking any existing connections.

☯ If we change the mobile device’s IP address, how do we communicate the change of

address to other devices on the Internet? These devices will only have the mobile

node’s original home address, which means they won’t be able to find it even if we give

it a new address matching its new location.

☯ Routing based on the entire address of a host would mean the entire Internet would be

flooded with routing information for each and every mobile computer. Considering how

much trouble has gone into developing technologies like classless addressing to

reduce routing table entries, it's obvious this is a Pandora's Box nobody wants to

touch.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 574 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Key Concept: The basic problem with supporting mobile devices in IP internetworks

is that routing is performed using the IP address, which means the IP address of a

device is tied to the network where that device is located. If a device changes

networks, data sent to its old address cannot be delivered by conventional means. Tradi-

tional workarounds such as routing by the full IP address or changing IP addresses

manually often create more problems.

A Better Solution: Mobile IP

The solution to these difficulties was to define a new protocol especially to support mobile

devices, which adds to the original Internet Protocol. This protocol, called IP Mobility

Support for IPv4, was first defined in RFC 2002, updated in RFC 3220, and is now

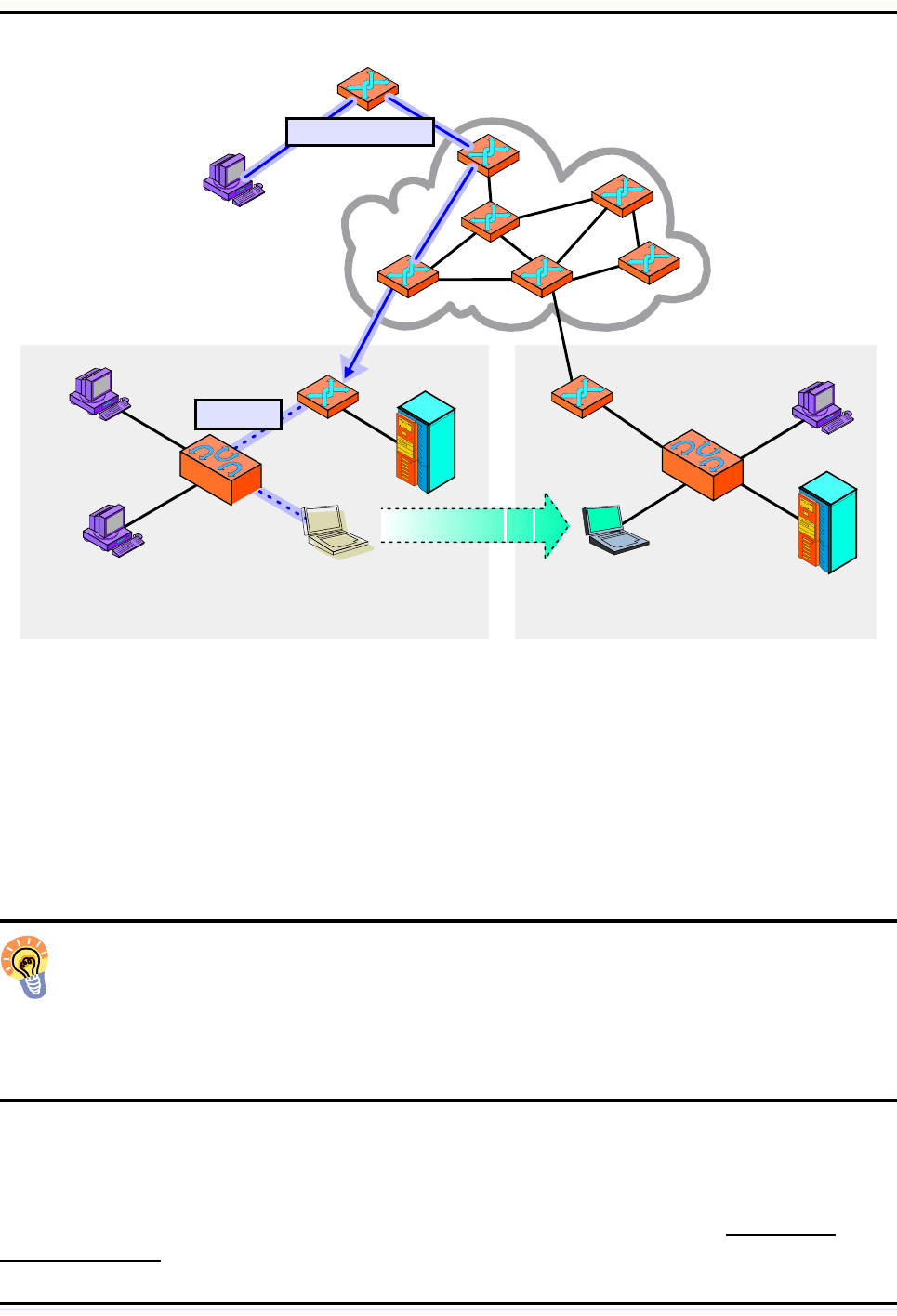

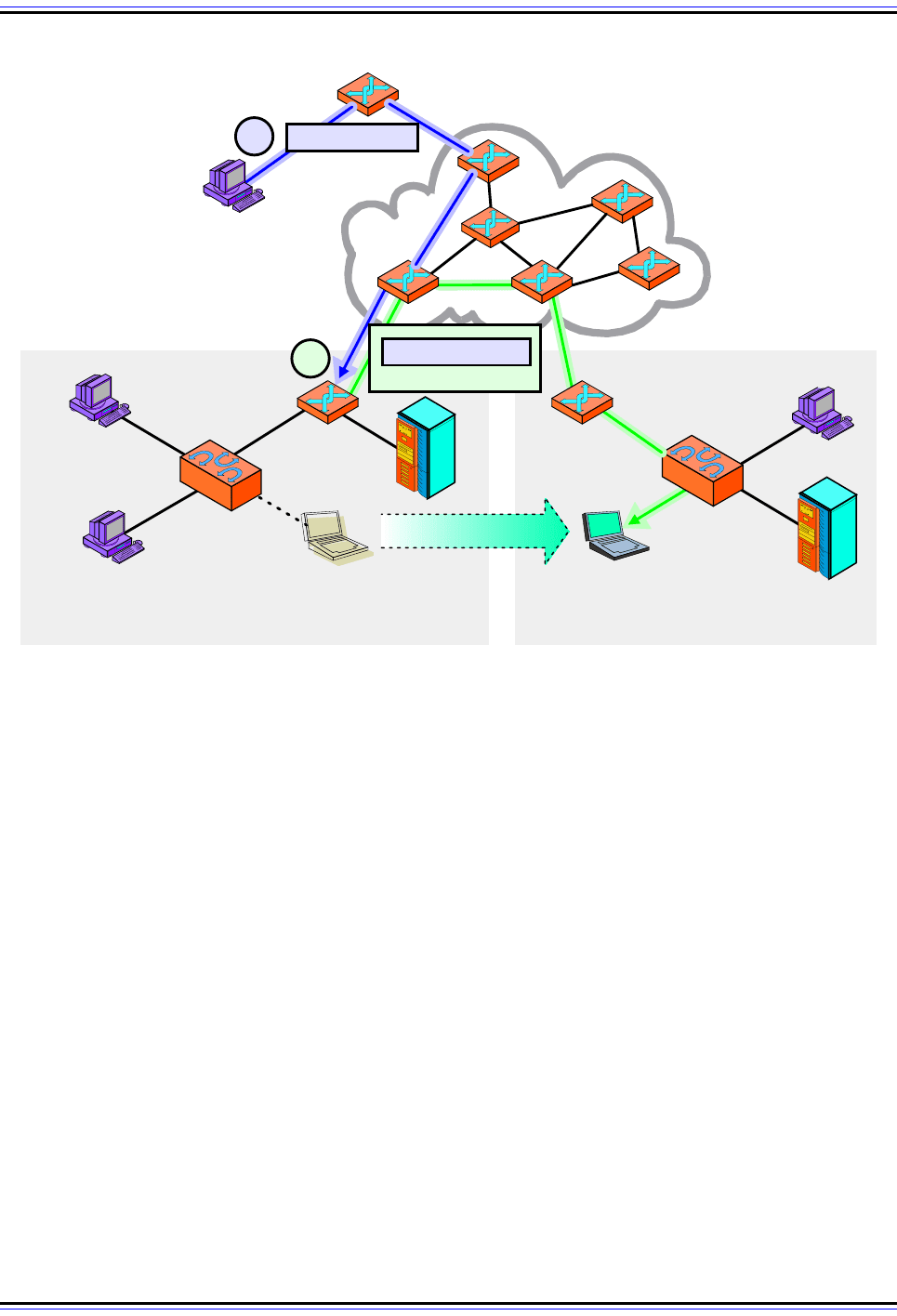

Figure 127: The Main Problem With Mobile Devices on IP Internetworks

In this example, a mobile device (the notebook PC) has been moved from its home network in London to

another network in Tokyo. A remote client (upper left) decides to send a datagram to the mobile device.

However, it has no idea the device has moved. Since it sends using the mobile node’s home address,

71.13.204.20, its request is routed to the router responsible for that network, which is in London. Of course the

mobile device isn’t there, so the router can’t deliver it. Mobile IP solves this problem by giving mobile devices

and routers the capability to forward datagrams from one location to another.

Foreign Network (Tokyo)

210.4.79.0/24

Home Network (London)

71.13.204.0/24

Mobile Node

Home Location

Home Address 71.13.204.20

Home

Router

Foreign

Router

To: 71.13.204.20

Mobile Node

Foreign Location

Foreign Address ??

To: ??

Remote

Client

Addess 56.1.78.22

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 575 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

described in RFC 3344. The formal name as given in that document title is rather long; the

technology is more commonly called Mobile IP both in the RFC itself and by networking

people.

To ensure its success, Mobile IP's designers had to meet a number of important goals. The

resulting protocol has these key attributes and features:

☯ Seamless Device Mobility Using Existing Device Address: Mobile devices can

change their physical network attachment method and location while continuing to use

their existing IP address.

☯ No New Addressing or Routing Requirements: The overall scheme for addressing

and routing as in regular IP is maintained. IP addresses are still assigned in the

conventional way, by the owner of each device. No new routing requirements are

placed on the internetwork, such as host-specific routes.

☯ Interoperability: Mobile IP devices can still send to and receive from existing IP

devices that do not know how Mobile IP works, and vice-versa.

☯ Layer Transparency: The changes made by Mobile IP are confined to the network

layer. Transport layer and higher layer protocols and applications are able to function

as in regular IPv4, and existing connections can even be maintained across a move.

☯ Limited Hardware Changes: Changes are required to the software in the mobile

device, as well as to routers used directly by the mobile device. Other devices,

however, do not need changes, including routers between the ones on the home and

visited networks.

☯ Scalability: Mobile IP allows a device to change from any network to any other, and

supports this for an arbitrary number of devices. The scope of the connection change

can be global; you could detach a notebook from an office in London and move it to

Australia or Brazil, for example, and it will work the same as if you took it to the office

next door.

☯ Security: Mobile IP works by redirecting messages, and includes authentication

procedures to prevent an unauthorized device from causing problems.

Mobile IP accomplishes these goals by implementing a forwarding system for mobile

devices. When a mobile unit is on its “home” network, it functions normally. When it moves

to a different network, datagrams are sent from its home network to its new location. This

allows normal hosts and routers that don't know about Mobile IP to continue to operate as if

the mobile device had not moved. Special support services are required to implement

Mobile IP, to allow activities such as letting a mobile device determine where it is, telling the

home network where to forward messages and more. I explore Mobile IP operation more in

the next topic, and the implementation specifics in the rest of this section.

Key Concept: Mobile IP solves the problems associated with devices that change

network locations, by setting up a system where datagrams sent to the mobile node’s

home location are forwarded to it wherever it may be located. It is particularly useful

for wireless devices but can be used for any device that moves between networks

periodically.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 576 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Mobile IP is often associated with wireless networks, since devices using WLAN technology

can move so easily from one network to another. However, it wasn't designed specifically

for wireless. It can be equally useful for moving from an Ethernet network in one building to

a network in another building, city or country. Mobile IP can be of great benefit in numerous

applications, including traveling salespeople, consultants who visit client sites, adminis-

trators that walk around a campus troubleshooting problems, and much more.

Limitations of Mobile IP

It’s important to realize that Mobile IP has certain limitations in its usefulness in a wireless

environment. It was designed to handle mobility of devices, but only relatively infrequent

mobility. This is due to the work involved with each change. This overhead isn't a big deal

when you move a computer once a week, a day or even an hour. It can be an issue for

“real-time” mobility such as roaming in a wireless network, where hand-off functions

operating at the data link layer may be more suitable. Mobile IP was designed under the

specific assumption that the attachment point would not change more than once per

second.

I should also point out that Mobile IP is intended to be used with devices that maintain a

static IP configuration. Since the device needs to be able to always know the identity of its

home network and normal IP address, it is much more difficult to use it with a device that

obtains an IP address dynamically, using something like DHCP.

Mobile IP Concepts and General Operation

I like analogies, as they provide a way of explaining often dry technical concepts in terms

we can all relate to. The problem of mobile devices in an IP internetwork can easily be

compared to a real-life mobility and information transmission problem: mail delivery for

those who travel. To help explain how Mobile IP works, I will set up this analogy and use it

as the basis for a look at Mobile IP's general operation. I will also refer back to it in

explaining certain concepts in the remaining topics in this section.

Mobile IP Overview: "Address Forwarding" for the Internet

Suppose you are a consultant working for a large corporation with many offices. Your home

office is in London, England, and you spend about half your time there. The rest of the time

is split between other offices in say, Rome, Tokyo, New York City and Toronto. You also

occasionally visit client sites that can be just about anywhere in the world. You may be at

these remote locations for weeks at a time.

The problem is: how do you arrange things so that you can receive your mail regardless of

your location? You have the same problem that regular IP has with a mobile device, and

without taking special steps, the same two unsatisfactory options for resolving it: address

changing or decoupling routing from your address. You can't change your address each

time you move because you would be modifying it constantly; by the time you told everyone

about your new address it would change again. And you certainly can't “decouple” the

routing of mail from your address, unless you want to set up your own postal system!

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 577 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

The solution to this dilemma of course is mail forwarding. Let's say that you leave London

for Tokyo for a couple of months. You tell the London post office (PO) that you will be in

Tokyo. They intercept mail headed for your normal London address, relabel it, and forward

it to Tokyo. Depending on where you are staying, this mail might be redirected either

straight to a new address in Tokyo, or to a Tokyo PO where you can pick it up. If you leave

Tokyo to go to another city, you just call the London PO and tell them your new location.

When you come home, you cancel the forwarding and get your mail as always. (Yes, I'm

assuming London and Tokyo each have only one post office. You mean they don't? Yeah,

whatever. ☺)

The advantages of this system are many. It is relatively simple to understand and

implement. It is also transparent to everyone who sends you mail; they still send to you in

London and it gets wherever it needs to go. And handling of the forwarding mechanism is

done only by the London PO and possibly the PO where you are presently located; the rest

of the postal system doesn't even know anything out of the ordinary is going on.

There are some disadvantages of course too. The London PO may allow occasional

forwarding for free, but would probably charge you if you did this on a regular basis. You

might also need a special arrangement in the city you travel to. You have to keep communi-

cating with your home PO each time you move. And perhaps most importantly, every piece

of mail has to be sent through the system twice—first to London and then to wherever you

are located—which is inefficient.

Mobile IP works in a manner very similar to the mail forwarding system I just described. The

“traveling consultant” is the device that goes from network to network. Each network can be

considered like a different “city”, and the internetwork of routers is like the postal system.

The router that connects any network to the Internet is like that network's “post office”, from

an IP perspective.

The mobile node is normally resident on its home network, which is the one that is indicated

by the network ID in its IP address. Devices on the internetwork always route using this

address, so the pieces of “mail” (datagrams) always arrive at a router at the device's

“home”. When the device “travels” to another network, the home router (“post office”) inter-

cepts these datagrams and forwards them to the device's current address. It may send

them straight to the device using a new, temporary address, or it may send them to a router

on the device's current network (the “other post office”, Tokyo in our analogy) for final

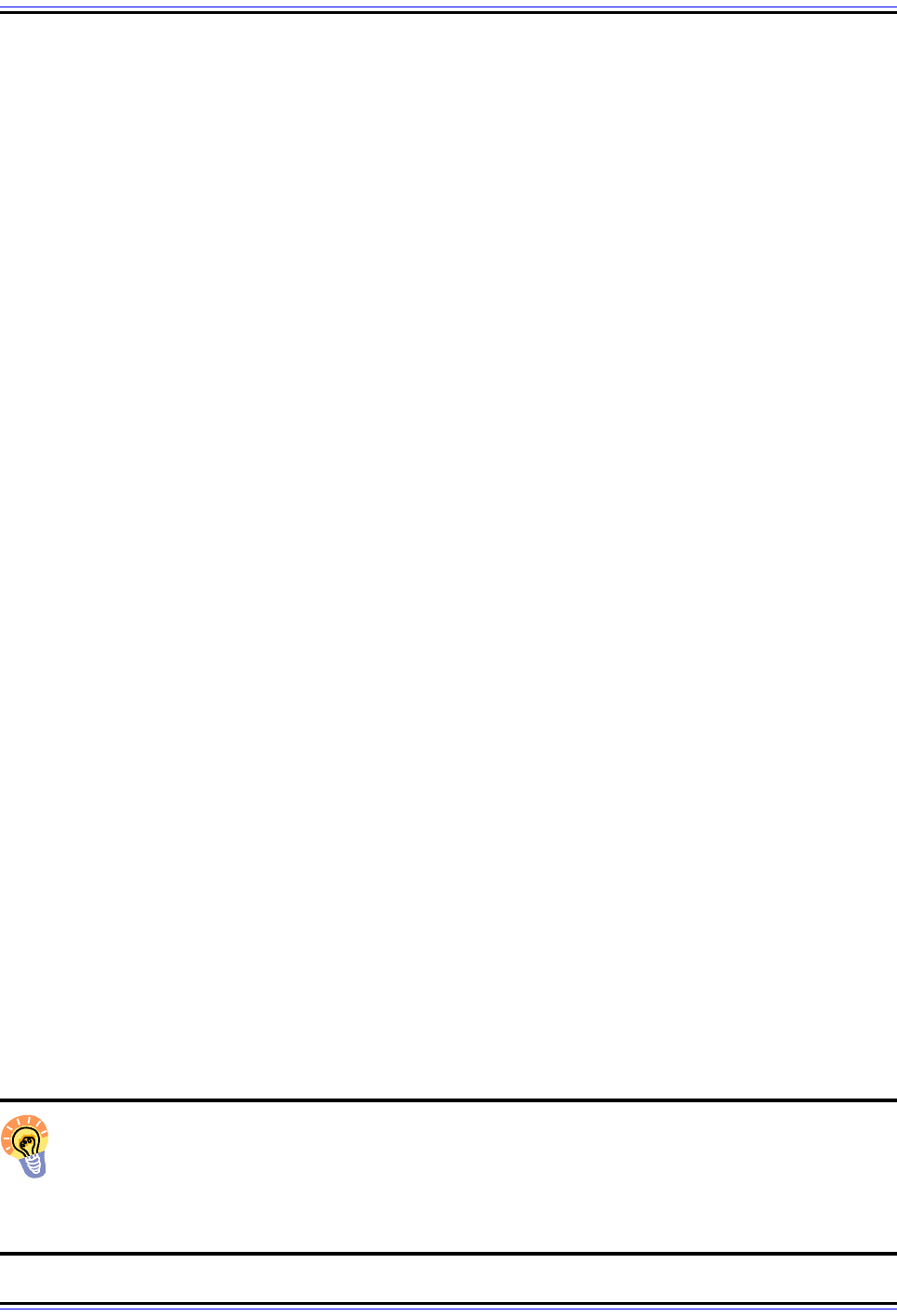

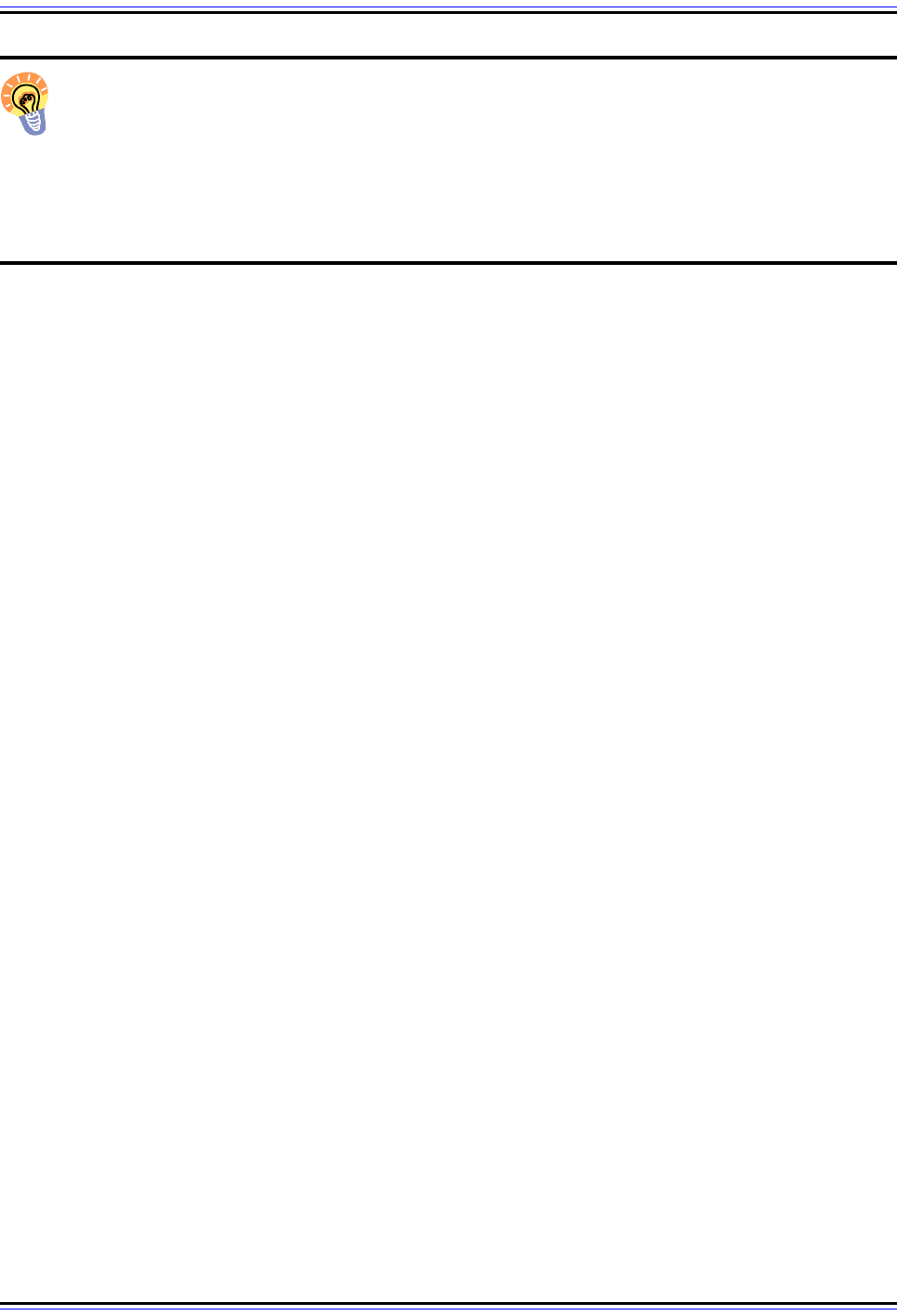

delivery. An overview of Mobile IP operation can be seen in Figure 128

.

Mobile IP Device Roles

As you can see, just as mail forwarding requires support from one or more post offices,

Mobile IP requires the help of two routers. In fact, special names are given to the three main

players that implement the protocol (also shown in Figure 128):

☯ Mobile Node: This is the mobile device, the one moving around the internetwork.

☯ Home Agent: This is a router on the home network that is responsible for catching

datagrams intended for the mobile node and forwarding them to it when it is traveling.

It also implements other support functions necessary to run the protocol.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 578 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

☯ Foreign Agent: This is a router on the network to which the mobile node is currently

attached. It serves as a “home away from home” for the mobile node, normally acting

as its default router as well as implementing Mobile IP functions. Depending on the

mode of operation, it may receive forwarded datagrams from the home agent and

forward them to the mobile node. It also supports the sharing of mobility information to

make Mobile IP operate. The foreign agent may not be required in some Mobile IP

implementations but is usually considered part of how the protocol operates.

Figure 128: General Operation of the Mobile IP Protocol

This diagram is like Figure 127, but with Mobile IP implemented. The mobile node’s home router serves as

home agent and the router in Tokyo as the foreign agent. The mobile has been assigned a temporary, “care-

of” address to use while in Tokyo (which in this case is a co-located care-of address, meaning that it is

assigned directly to the mobile node; Figure 129 shows the same example using the other type of care-of

address). In step #1, the remote client sends a datagram to the mobile using its home address, as before. It

arrives in London as usual. In step #2, the home agent encapsulates that datagram in a new one and sends it

to the mobile node in Tokyo.

Foreign Network (Tokyo)

210.4.79.0/24

Home Network (London)

71.13.204.0/24

Mobile Node

Home Location

Home Address 71.13.204.20

Remote

Client

Addess 56.1.78.22

Home

Age nt

To: 71.13.204.20

Mobile Node

Foreign Location

Care-Of Address 210.4.79.19

Tunnel To: 210.4.79.19

To: 71.13.204.20

#2

#1

Foreign

Age nt

210.4.79.2

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 579 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Key Concept: Mobile IP operates by setting up the TCP/IP equivalent of a mail

forwarding system. A router on a mobile node’s home network serves as the mobile

device’s home agent, and one on its current network acts as the foreign agent. The

home agent receives datagrams destined for the mobile’s normal IP address and forwards

them to the mobile node’s current location, either directly or by sending to the foreign agent.

The home agent and foreign agent are also responsible for various communication and

setup activities that are required for Mobile IP to work.

Mobile IP Functions

An important difference between Mobile IP and our mail forwarding example is one that

represents the classic distinction between people and computers: people are smart and

computers are not. When our consultant is traveling in Tokyo, he always knows he's in

Tokyo and that his mail is being forwarded. (Well, assuming he goes easy on the sake, but

that's a different story. ☺) He knows to go deal with the Tokyo post office to get his mail. The

post office in London knows what forwarding is all about and how to do it. The traveler and

the post offices all can communicate easily using the telephone.

In contrast, in the computer world, when a device travels using Mobile IP, things are more

complicated. Suppose our consultant flies to Tokyo, turns on his notebook and plugs it in to

the network. When the notebook is first turned on, it has no clue what is going on. It has to

figure out that it is in Tokyo. It needs to find a foreign agent in Tokyo. It needs to know what

address to use while in Tokyo. It needs to communicate back with its home agent back in

London to tell it that it is in Tokyo and to start forwarding datagrams. Furthermore, it must

accomplish its communication without any “telephone”.

To this end, Mobile IP includes a host of special functions that are used to set up and

manage datagram forwarding. To see how these support functions work, we can describe

the general operation of Mobile IP as a simplified series of steps:

1. Agent Communication: The mobile node finds an agent on its local network by

engaging in the Agent Discovery process. It listens for Agent Advertisement messages

sent out by agents and from this can determine where it is located. If it doesn't hear

these messages it can ask for one using an Agent Solicitation message.

2. Network Location Determination: The mobile node determines whether it is on its

home network or a foreign one by looking at the information in the Agent Adver-

tisement message.

If it is on its home network it functions using regular IP. To show how the rest of the process

works, let's say the device sees that it just moved to a foreign network. The remaining steps

are:

3. Care-Of Address Acquisition: The device obtains a temporary address called a

care-of address. This either comes from the Agent Advertisement message from the

foreign agent, or through some other means. This address is used only as the desti-

nation point for forwarding datagrams, and for no other purpose.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 580 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

4. Agent Registration: The mobile node informs the home agent on its home network of

its presence on the foreign network and enables datagram forwarding, by registering

with the home agent. This may be done either directly between the node and the home

agent, or indirectly using the foreign agent as a conduit.

5. Datagram Forwarding: The home agent captures datagrams intended for the mobile

node and forwards them. It may send them either directly to the node or indirectly to

the foreign agent for delivery, depending on the type of care-of address in use.

Datagram forwarding continues until the current agent registration expires. The device can

then renew it. If it moves again, it repeats the process to get a new care-of address and

then registers its new location with the home agent. When the mobile node returns back to

its home network, it deregisters to cancel datagram forwarding and resumes normal IP

operation.

The following topics look in more detail at the functions summarized in each of the steps

above.

Mobile IP Addressing: Home and "Care-Of" Addresses

Just as most of us have only a single address used for our mail, most IP devices have only

a single address. Our traveling consultant, however, needs to have two addresses; a

normal one and one that is used while he is away. Continuing our earlier analogy, the

Mobile-IP-equipped notebook our consultant carries needs to have two addresses as well:

☯ Home Address: The “normal”, permanent IP address assigned to the mobile node.

This is the address used by the device on its home network, and the one to which

datagrams intended for the mobile node are always sent.

☯ Care-Of Address: A secondary, temporary address used by a mobile node while it is

'traveling” away from its home network. It is a normal 32-bit IP address in most

respects, but is used only by Mobile IP for forwarding IP datagrams and for adminis-

trative functions. Higher layers never use it, nor do regular IP devices when creating

datagrams.

Mobile IP Care-Of Address Types

The care-of address is a slightly tricky concept. There are two different types, which corre-

spond to two distinctly different methods of forwarding datagrams from the home agent

router.

Foreign Agent Care-Of Address

This is a care-of address provided by a foreign agent in its Agent Advertisement message.

It is, in fact, the IP address of the foreign agent itself. When this type of care-of address is

used, all datagrams captured by the home agent are not relayed directly to the mobile node,

but indirectly to the foreign agent, which is responsible for final delivery. Since in this

arrangement the mobile node has no distinct IP address valid on the foreign network, this is

typically done using a layer two technology. This arrangement is illustrated in Figure 129.