Charles M. Kozierok The TCP-IP Guide

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1481 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Most people today don't know UNIX and don't want to know it. They are much happier using

a fancy graphical e-mail program based on POP3 or IMAP4. However, there are still a

number of us old UNIX dinosaurs around who feel the benefits of direct access outweigh

the drawbacks. Oh, one other benefit that I forgot to mention is that it's very hard to get a

virus in e-mail when you use UNIX.

Key Concept: Instead of using a dedicated protocol like POP3 or IMAP4 to retrieve

mail, on some systems it is possible for a user to have direct server access to e-mail.

This is most commonly done on UNIX systems, where protocols like Telnet or NFS

can give a user shared access to mailboxes on a server. This is the oldest method of e-mail

access; it provides the user with the most control over his or her mailbox, and is well-suited

to those who must access mail from many locations. The main drawback is that it means

the user must be on the Internet to read e-mail, and it also usually requires familiarity with

the UNIX operating system, which few people use today.

TCP/IP World Wide Web Electronic Mail Access

I don't know about you, but I was pretty darned glad when bell bottoms went out of style…

and then, rather mortified when they came back in style a few years ago! That's the way the

world of fashion is, I suppose. And sometimes, even in networking, “what's old is new

again”. In this case, I am referring to the use of the online TCP/IP e-mail access model.

Most e-mail users like the advantages of online access, especially the ability to read mail

from a variety of different machines. What they don't care for is direct server access using

protocols like Telne t (“Tel-what?”), UNIX (“my father used to use that I think…” ☺) and non-

intuitive, character-based e-mail programs. They want online access but they want it to be

simple and easy to use.

In the 1990s, the World Wide Web was developed and grew in popularity very rapidly, due

in large part to its ease of use. Millions of people became accustomed to firing up a Web

browser to perform a variety of different tasks, to the point where using the Web became

almost “second nature”. It didn't take very long before someone figured out that using the

Web would be a natural way of providing easy access to e-mail on a server. This is now

sometimes called Webmail.

How Web-Based E-Mail Works

This technique is straight-forward: it exploits the flexibility of the Hypertext Transfer Protocol

(HTTP) to informally “tunnel” e-mail from a mailbox server to the client. A Web browser

(client) is opened and given a URL for a special Web server document that accesses the

user's mailbox. The Web server reads information from the mailbox and sends it to the Web

browser, where it is displayed to the user.

This method uses the online access model like direct server access, because requests

must be sent to the Web server, and this requires the user to be online. The mail also

remains on the server as when NFS or Telnet are used.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1482 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Pros and Cons of Web-Based E-Mail Access

The big difference between Web-based mail and the UNIX methods is that the former is

much easier for non-experts to use. Since the idea was first developed, many companies

have jumped on the Web-mail bandwagon, and the number of people using this technique

has exploded into the millions in just a few years. Many free services even popped up in the

late 1990s as part of the “dot com bubble”, allowing any Internet user to send and receive e-

mail using the Web at no charge (except perhaps for tolerating advertising). Many Internet

Service Providers (ISPs) now offer Web access as an option in additional to conventional

POP/IMAP access, which is useful for those who travel. Google’s new Gmail service is the

latest entrant into the sweepstakes, offering users 1 GB of e-mail storage in exchange for

viewing Google’s text ads on their site.

There are drawbacks to the technique, however, which as you might imagine are directly

related to its advantages. Web-based mail is easy to use, but inflexible; the user does not

have direct access to his or her mailbox, and can only use whatever features the provider's

Web site implements. For example, suppose the user wants to search for a particular string

in his or her mailbox; this requires that the Web interface provide this function. If it doesn't,

the user is out of luck.

Web-based mail also has a disadvantage that is an issue for some people: performance.

Using conventional UNIX direct access, it is easy to quickly read through a mailbox; the

same is true of access using POP3, once the mail is downloaded. In contrast, Web-based

mail services mean each request requires another HTTP request/response cycle. The fact

that many Web-based services are free often means server overload that exacerbates the

speed issue.

Note that when Web-based mail is combined with other methods such as POP3, care must

be taken to avoid strange results. If the Web interface doesn't provide all the features of the

conventional e-mail client, certain changes made by the client may not show up when Web-

based access is used. Also, mail retrieval using POP3 by default removes the mail from the

server. If you use POP3 to read your mailbox and then later try to use the Web to access

those messages from elsewhere, you will find that the mail is “gone”—it's on the client

machine where you used the POP3 client. Many e-mail client programs now allow you to

specify that you want the mail left on the server after retrieving it using POP3.

Key Concept: In the last few years a new method has been developed to allow e-

mail access using the World Wide Web (WWW). This technique is growing in

popularity rapidly, because it provides many of the benefits of direct server access,

such as the ability to receive e-mail anywhere around the world, while being much simpler

and easier than the older methods of direct access such as making a Telnet connection to a

server. WWW-based e-mail can in some cases be used in combination with other methods

or protocols, such as POP3, giving users great flexibility in how they read their mail.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1483 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Usenet (Network News) and the TCP/IP Network News Transfer

Protocol (NNTP)

Electronic mail is one of the “stalwarts” of message transfer on the modern Internet, but is

really designed only for communication within a relatively small group of specific users.

There are many situations in which e-mail is not ideally suited, such as when information

needs to be shared amongst a large number of participants, not all of whom may neces-

sarily even know each other. One classic example of this is sharing news; the person

providing news often wants to make it generally available to anyone who is interested,

rather than specifying a particular set of recipients.

For distributing news and other types of general information over internetworks, a

messaging system called both Usenet (for user's network) and Network News was created.

This application is like e-mail in allowing messages to be written and read by large numbers

of users. However, it is designed using a very different model than e-mail, focused on public

sharing and feedback. In Usenet, anyone can write a message that can be read by any

number of recipients, and can likewise respond to messages written by others. Usenet was

one of the first widely-deployed internetwork-based group communication applications, and

has grown into one of the largest online communities in the world, used by millions of

people for sharing information, asking questions and discussing thousands of different

topics.

In this section I describe Usenet in detail, discussing in two subsections how it is used and

how it works. The first subsection covers Usenet in general terms, discussing its history and

the model it uses for communication and message storage and formatting. The second

describes the Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP), the protocol currently used widely

to implement Usenet communication in TCP/IP.

Many people often equate the Usenet system as a whole with the NNTP protocol that is

used to carry Usenet messages on the Internet. They are not the same however; Usenet

predates NNTP, which is simply a protocol for conveying Usenet messages. Usenet old-

timers will be quick to point this out, if you try to say Usenet and NNTP are the same on

Usenet itself. ☺ This is one of the reasons why I have separated my discussion into two

subsections. In the overview of Usenet I do briefly discuss the methods other than NNTP

that have been used in the past to move Usenet messages, but since they are not widely

used today I do not place a great deal of emphasis on them.

Background Information: There are several aspects of how Usenet works that

are closely related to the standards and techniques used for e-mail. I assume in

this section that you have basic familiarity with how e-mail works. If you have not

read the section on e-mail, please at least review the overview of the e-mail system, and

also read the section on the e-mail message format, since Usenet messages are based

directly on the RFC 822 e-mail message standard.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1484 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Usenet Overview, Concepts and General Operation

Where electronic mail is the modern equivalent of the hand-written letter or the inter-office

memo, Usenet is the updated version of the company newsletter, the cafeteria bulletin

board, the coffee break chat, and the water cooler gossip session, all rolled into one.

Spread worldwide over the Internet, Usenet newsgroup messages provide a means for

people with common interests to form online communities, to discuss happenings, solve

problems, and provide support to each other—as well as facilitating plain old socializing and

entertainment.

In this section I discuss Usenet as a whole and how it operates. I begin with an overview

and history of Usenet. I then provide a high-level look at the model of communication

employed by Usenet, discussing how messages are created, propagated, stored and read.

I discuss the Usenet addressing mechanism, which takes the form of a hierarchical set of

newsgroups. I also explain how Usenet messages are formatted and discuss the special

headers that provide information about a message and control how it is displayed and

communicated.

Usenet Overview, History and Standards

We are by nature both highly social and creative animals, and as a result, are always

finding new ways to communicate. It did not take long after computers were first connected

together for it to be recognized that those interconnections provided the means to link

together people as well. The desire to use computers to create an online community led to

the creation of Usenet over two decades ago.

History of Usenet

Like almost everything associated with networking, Usenet had very humble beginnings. In

1979, Tom Truscott was a student at Duke University in North Carolina, and spent the

summer as an intern at Bell Laboratories, the place where the UNIX operating system was

born. He enjoyed the experience so much that when he returned to school that autumn, he

missed the intensive UNIX environment at Bell Labs. He used the Unix-to-Unix Copy

Protocol (UUCP) to send information from his local machine to other machines and vice-

versa, including establishing electronic connectivity back to Bell Labs.

Building on this idea, Truscott and a fellow Duke student, Jim Ellis, teamed up with other

UNIX enthusiasts at Duke and the nearby University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, to

develop the idea of an online community. The goal was to create a system where students

could use UNIX to write and read messages, to allow them to obtain both technical help and

maintain social contacts. The system was designed based on an analogy to an online

newsletter that was open to all users of a connected system. To share information,

messages were posted to newsgroups, where any user could access the messages to read

them and respond to them as well.

The early work at Duke and UNC Chapel Hill resulted in the development of both the initial

message format and the software for the earliest versions of this system, which became

known both as Network News (Net News) and Usenet (a contraction of User's network). At

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1485 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

first, the system had just two computers, sharing messages posted in a pair of different

newsgroups. The value of the system was immediately recognized, however, and soon

many new sites were added to the system. These sites were arranged in a structure to

allow messages to be efficiently passed using direct UUCP connections. The software used

for passing news articles also continued to evolve and become more capable, as did the

software for reading and writing articles.

The newsgroups themselves also changed over time. Many new newsgroups were created,

and a hierarchical structure defined to help keep the newsgroups organized in a meaningful

way. As more sites and users joined Usenet, more areas of interest were identified. Today

there are a staggering number of Usenet newsgroups: over 100,000. While many of these

groups are not used, there are many thousands of active ones that discuss nearly every

topic imaginable, from space exploration, to cooking, to biochemistry, to PC trouble-

shooting, to raising horses. There are also regional newsgroups devoted to particular areas;

for example, there is a set of newsgroups for discussing events in Canada; another for

discussing happenings in the New York area, and so on.

Overview of Usenet Operation and Characteristics

Usenet begins with a user writing a message to be distributed. After the message is posted

to say, the group on TCP/IP networking, it is stored on that user's local news server, and

special software sends copies of it to other connected news servers. The message

eventually propagates around the world, where anyone who chooses to read the TCP/IP

networking newsgroup can see the message.

The real power of Usenet is that after reading a message, any user can respond to it on the

same newsgroup. Like the original message, the reply will propagate to each connected

system, including the one used by the author of the original message. This makes Usenet

very useful for sharing information about recent happenings, for social discussions, and

especially for receiving assistance about problems, such as resolving technical glitches or

getting help with a diet program.

What is particularly interesting about Usenet is that it is not a formalized system in any way,

and is not based on any formally defined standards. It is a classic example of the devel-

opment of a system in an entirely “ad hoc” manner; the software was created, people

started using it, the software was refined, and things just took off from there. Certain

standards have been written to codify how Usenet works—such as RFC 1036, which

describes the Usenet message format—but these serve more as historical documents than

as prescriptive standards.

There is likewise no “central authority” that is responsible for Usenet's operation, even

though new users often think there is one. Unlike a dial-up bulletin board system or Web-

based forum, Usenet works simply by virtue of cooperation between sites; there is no

“manager in charge”. Usenet is for this reason sometimes called an “anarchy”, but this is

not accurate. It isn't the case that there are no rules, only that it is the managers of partici-

pating systems that make policy decisions such as what newsgroups to support. There are

also certain “dictatorial” aspects of the system, in that only certain people (usually system

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1486 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

administrators) can decide whether to create some kinds of new newsgroups. The system

also has “socialistic” elements in that machine owners are expected to share messages

with each other. So the simplified political labels really don't apply to Usenet at all.

Every community has a culture, and the same is true of online communities, including

Usenet. There is an overall culture that prescribes acceptable behavior on Usenet, and also

thousands of newsgroup-specific “cultures” in Usenet, each of which has evolved through

the writings of thousands of participants over the years. There are even newsgroups

devoted to explaining how Usenet itself operates, where you can learn about newbies (new

users), netiquette (rules of etiquette for posting messages) and related subjects.

Usenet Transport Methods

As I said earlier, Usenet messages were originally transported using UUCP, which was

created to let UNIX systems communicate directly, usually using telephone lines. For many

years, all Usenet messages were simply sent from machine to machine using computerized

telephone calls (just as e-mail once was). Each computer joining the network would connect

to one already on Usenet and receive a feed of messages from it periodically; the owner of

that computer had in turn to agree to provide messages to other computers.

Once TCP/IP was developed in the 1980s and the Internet grew to a substantial size and

scope, it made sense to start using it to carry Usenet messages rather than UUCP. The

Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) was developed specifically to describe the

mechanism for communicating Usenet messages over TCP. It was formally defined in RFC

977, published in 1986, with NNTP extensions described in RFC 2980, October 2000.

For many years Usenet was carried using both NNTP and UUCP, but NNTP is now the

mechanism used for the vast majority of Usenet traffic, and for this reason is the primary

focus of my Usenet discussion in this Guide. NNTP is employed not only to distribute

Usenet articles to various servers, but also for other client actions such as posting and

reading messages. It is thus used for most of the steps in Usenet message communication.

It is because of the critical role of NNTP and the Internet in carrying messages in today’s

Usenet that the concepts are often confused. It's essential to remember, however, that

Usenet does not refer to any type of physical network or internetworking technology; rather,

it is a logical network of users. That logical network has evolved from UUCP data transfers

to NNTP and TCP/IP, but Usenet itself is the same.

Today, Usenet faces “competition” from many other group messaging applications and

protocols, including Web-based bulletin board systems and chat rooms. After a quarter of a

century, however, Usenet has established itself and is used by millions of people every day.

While to some, the primarily text-based medium seems archaic, it is a mainstay of global

group communication and likely to continue to be so for many years to come.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1487 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Key Concept: One of the very first online electronic communities was set up in 1979

by university students who wanted to keep in touch and share news and other infor-

mation. Today, this User’s Network (Usenet), also called Network News, has grown

into a logical network that spans the globe. By posting messages to a Usenet newsgroup,

people can share information on a variety of subjects of interest. Usenet was originally

implemented in the form of direct connections established between participating hosts;

today the Internet is the vehicle for message transport

Usenet Communication Model: Message Composition, Posting, Storage,

Propagation and Access

When the students at Duke University decided to create their online community, electronic

mail was already in wide use, and there were many mailing lists in operation as well. E-mail

was usually transported using UUCP during these pre-Internet days, the same method that

Usenet was designed to employ. The obvious question then was, why not simply use e-mail

to communicate between sites?

The main reason is that e-mail is not really designed to facilitate the creation of an online

community where information can be easily shared in a group. The main issue with e-mail

in this respect is that only the individuals who are specified as recipients of a message can

read it. There is no facility whereby someone can write a message and put it in an open

place where anybody who wants can read it, analogous to posting a newsletter in a public

place.

Another problem with e-mail in large groups is related to efficiency: if you put 1,000 people

on a mailing list, each message sent to that list must be duplicated and delivered 1,000

times. Early networks were limited in bandwidth and resources; using e-mail for wide-scale

group communication was possible, but far from ideal.

Key Concept: While electronic mail can be used for group communications, it has

two important limitations. First, a message must be specifically addressed to each

recipient, making public messaging impossible. Second, each recipient requires

delivery of a separate copy of the message, so sending a message to many recipients

means the use of a large amount of resources.

Usenet's Public Distribution Orientation

To avoid the problems of using e-mail for group messaging, Usenet was designed using a

rather different communication and message-handling model than e-mail. The defining

difference between the Usenet communication model and that used for e-mail is that

Usenet message handling is oriented around the concept of public distribution, rather than

private delivery to an individual user. This affects every aspect of how Usenet communi-

cation works:

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1488 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

☯ Addressing: Messages are not addressed from a sender to any particular recipient or

set of recipients, but rather to a group, which is identified with a newsgroup name.

☯ Storage: Messages are not stored in individual mailboxes but in a central location on a

server, where any user of the server can access them.

☯ Delivery: Messages are not conveyed from the sender's system to the recipient's

system, but are rather spread over the Internet to all connected systems so anyone

can read them.

The Usenet Communication Process

To help illustrate in more detail how Usenet communication works, let's take a look at the

steps involved in the writing, transmission and reading of a typical Usenet message (also

called an article—the terms are used interchangeably). Let's suppose the process begins

with a user, Ellen, posting a request for help with a sick horse to the newsgroup misc.rural.

Since she is posting the message, she would be known as the message poster. Simplified,

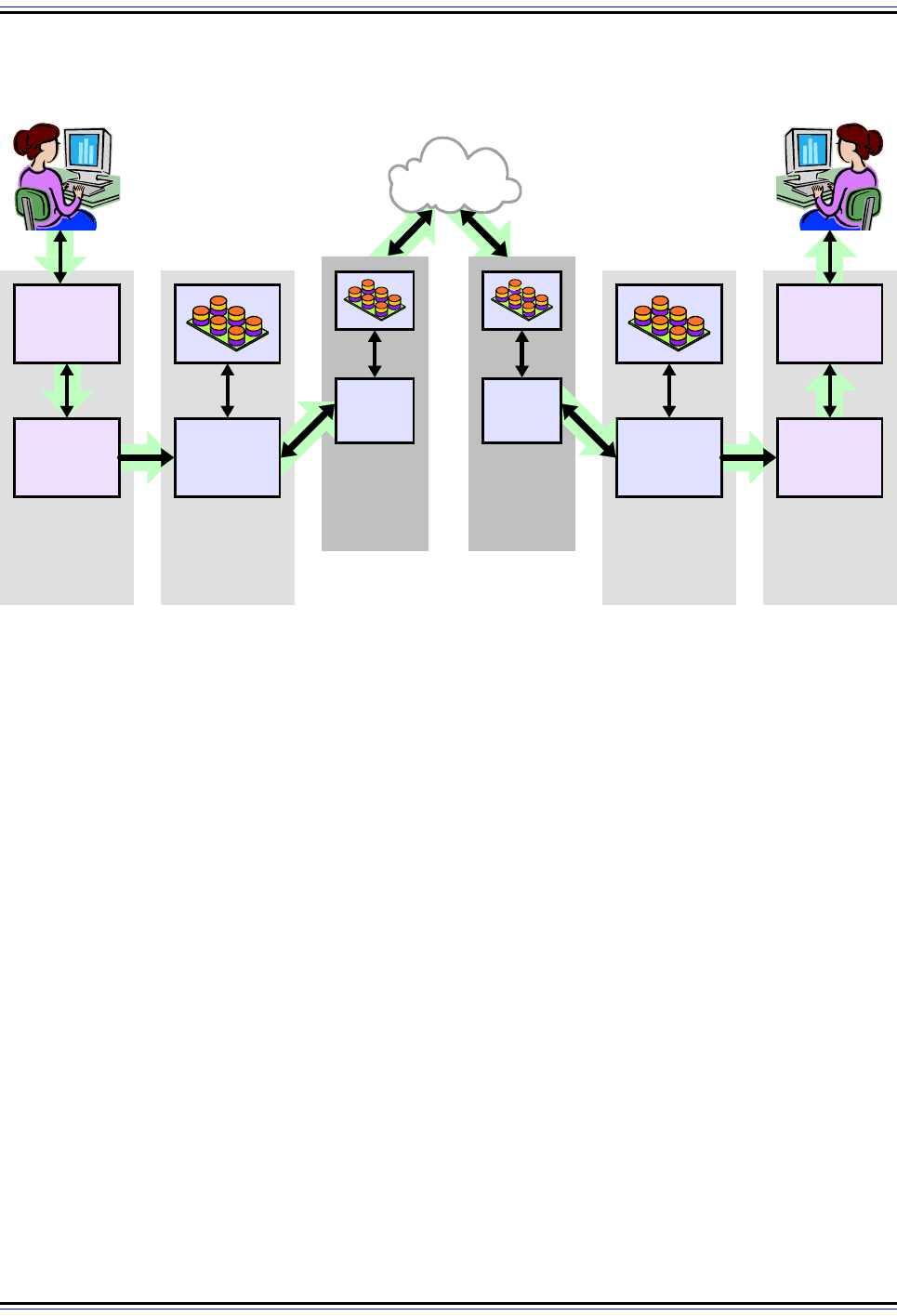

the steps in the process (illustrated in Figure 310) are as follows:

1. Article Composition: Ellen begins by creating a Usenet article, which is structured

according to the special message format required by Usenet. This message is similar

to an electronic mail message in that it has a header and a body. The body contains

the actual message to be sent, while the header contains header lines that describe

the message and control how it is delivered. For example, one important header line

specifies which newsgroup(s) for which the article is intended.

2. Article Posting and Local Storage: After completing her article, Ellen submits the

article to Usenet, a process called posting. A client software program on Ellen's

computer transmits Ellen's message to her local Usenet server. The message is stored

in an appropriate file storage area on that server. It is now immediately available to all

other users of that server who decide to read misc.rural.

3. Article Propagation: At this point, Ellen's local server is the only one that has a copy

of her message. The article must be sent to other sites, a process called distribution,

or more commonly, propagation. Ellen's message would travel from her local Usenet

server to other servers to which her server directly connects. It would then in turn

propagate from those servers to others they connect to, and so on, until all Usenet

servers that want it have a copy of the message.

4. Article Access and Retrieval: Since Usenet articles are stored on central servers, in

order to read them they must be accessed on the server. This is done using a Usenet

newsreader program. For example, some other reader of misc.rural named Jane might

access that group and find Ellen's message. If Jane was able to help Ellen she could

reply to Ellen by posting an article of her own. This would then propagate back to

Ellen's server, where she could read it and reply in turn. Of course, all other readers of

misc.rural could jump in to the conversation at any time as well, which is what makes

Usenet so useful for group communication.

Message Propagation and Server Organization

Propagation is definitely the most complex part of the Usenet communication process. In

the “olden dayse”, UUCP was used for propagation; each Usenet server would be

programmed to regularly dial up another server and give it all new articles it had received

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1489 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

since the last connection. Articles would flood across Usenet from one server to another.

This was time-consuming and inefficient, however, and only worked because the volume of

articles was relatively small.

In modern Usenet, the Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) is used for all stages of

transporting messages between devices. Articles are posted using an NNTP connection

between a client machine and a local server, which then uses the same protocol to

propagate the articles to other adjacent NNTP servers. NNTP is also used by client

newsreader software to retrieve messages from a server.

NNTP servers are usually arranged in a hierarchy of sorts, with the largest and fastest

servers providing service to smaller servers “downstream” from them. Depending on how

the connections are arranged, an NNTP server may either establish a connection to

Figure 310: Usenet (Network News) Communication Model

This figure illustrates the method by which messages are created, propagated and read using NNTP on

modern Usenet; it is similar in some respects to the e-mail model diagram of Figure 301. In this example a

message is created by the poster, Ellen, and read by a reader, Jane. The process begins with Ellen creating a

message in an editor and posting it. Her NNTP client sends it to her local NNTP server. It is then propagated

from that local server to adjacent servers, usually including its upstream server, which is used to send the

message around the Internet. Other NNTP servers receive the message, including the one upstream from

Jane’s local server. It passes the message to Jane’s local server, and Jane accesses and reads the message

using an NNTP client.

Jane could respond to the message, in which case the same process would repeat, but going in the opposite

direction, back to Ellen (and of course, also back to thousands of other readers, not shown here.)

Poster's

Client

Usenet

Reader/

Editor

NNTP

Client

Poster

(Ellen)

Poster's

NNTP

Server

NNTP

Server

Reader

(Jane)

Internet

Reader's

Client

Usenet

Reader/

Editor

NNTP

Client

Reader's

NNTP

Server

NNTP

Server

Upstream

NNTP

Server

NNTP

Server

Upstream

NNTP

Server

NNTP

Server

...

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1490 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

immediately send a newly-posted article to an “upstream” server for distribution to the rest

of Usenet, or the server may passively wait for a connection from the upstream server to

ask if there are any new articles to be sent. With the speed of the modern Internet, it

typically takes only a few minutes or even seconds for articles to propagate from one server

to another, even across continents.

It is also possible to restrict the propagation of a Usenet message, a technique often used

for discussions that are only of relevance in certain regions or on certain systems.

Discussing rural issues such as horses is of general interest, and Ellen might well find her

help anywhere around the world, so global propagation of her message makes sense.

However, if Ellen lived in the Boston area and was interested in knowing the location of a

good local steak-house, posting a query to ne.food (New England food discussions) with

only local distribution would make more sense. There are also companies that use Usenet

to provide “in-house” newsgroups that are not propagated off the local server at all. Note,

however, that because so many news providers are now national or international, limiting

the distribution of messages has largely fallen out of practice.

This is, of course, only a simplified look at Usenet communication. The section on NNTP

provides more details, especially on how articles are handled and propagated.

Key Concept: Usenet communication consists of four basic steps. A message is first

composed and then posted to the originator’s local server. The third step is propa-

gation, where the message is transmitted from its original server to others on the

Usenet system. The last step in the process is article retrieval, where other members of the

newsgroup access and read the article. The Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) is the

technology used for moving Usenet articles from one host to the next.

Usenet Addressing: Newsgroups, Newsgroup Hierarchies and Types

As the previous topic mentioned, a key concept in Usenet communication is the newsgroup.

Newsgroups are in fact the addressing mechanism for Usenet, and sending a Usenet article

to a newsgroup is equivalent to sending e-mail to an electronic mail address. Newsgroups

are analogous to other group communication venues such as mailing lists, chat rooms,

Internet Relay Chat channels or BBS forums—though calling a newsgroup a “list”, “room”,

“channel” or “BBS” is likely to elicit a negative reaction from Usenet old-timers.

Like any addressing mechanism, newsgroups must be uniquely identifiable. Each

newsgroup has a newsgroup name that describes what the topic of the newsgroup is about,

and differentiates it from other newsgroups. Since there are many thousands of different

newsgroups, they are arranged into sets called hierarchies. Each hierarchy contains a tree

structure of related newsgroups.