Charles M. Kozierok The TCP-IP Guide

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1391 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

TCP/IP Electronic Mail RFC 822 Standard Message Format Header Field Definitions

and Groups

The RFC 822 message format describes the structure and content of TCP/IP e-mail

messages. The structure is intentionally designed to be very simple and easy to both create

and understand. Each message begins with a set of headers that describe the message

and its contents. An empty line marks the end of the headers, and then the message body

follows.

The message body contains the actual text that the sender is trying to communicate to the

recipient(s), while the message header contains various types of information that serve

various purposes. The headers help control how the message is processed, by specifying

who the recipients are, describing the contents of the message, and providing information

to a recipient of a message about processing done on the message as it was delivered.

Header Field Structure

Each header field follows the simple text structure we saw in the preceding topic:

<header name>: <header value>

The <header name> is of course the name of the header, and the <header value> is the

value associated with that header, which depends on the header type. Like all RFC 822

lines, headers must be no more than 998 characters long and are recommended to be no

more than 78 characters in length, for easier readability. The RFC 822 and 2822 standards

support a special syntax for allowing headers to be “folded” onto multiple lines if they are

very lengthy. This is done by simply continuing a header value onto a new line, which must

begin with at least one “white space” character, such as a space or <Tab> character, like

this:

<header name>: <header value part 1>

<white space> <header value part 2>

<white space> <header value part 3>

…

The <Tab> character is most often used for this purpose. So, for example, if we wanted to

specify a large number of recipients for a message, we could do it as follows:

To: person1@domain1.org, person2@domain2.com,

person3@domain3.net, person4@domain4.edu

Header Field Groups

The RFC 822 message format specifies many types of headers that can be included in e-

mail messages. A small number of headers are mandatory, meaning they must be included

in all messages. Some are not mandatory but are usually present, because they are funda-

mental to describing the message. Others are optional and are included only when needed.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1392 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

To help organize the many headers, the RFC 2822 standard categorizes them into header

field groups (as did RFC 822, though the groups are a little different in the older standard):

☯ Origination Date Field: Specifies the date and time that the message was made

ready for delivery; see below for details. (This field is in its own group for reasons that

are unclear to me; perhaps just because it is important.)

☯ Originator Fields: Contain information about the sender of the message.

☯ Destination Address Fields: Specify the recipient(s) of the message, which may be

in one of three different recipient classes.

☯ Identification Fields: Contain information to help identify the message.

☯ Informational Fields: Contain optional information to help make more clear to the

recipient what the message is about.

☯ Resent Fields: Used to preserve the original originator, destination and other fields

when a message is resent.

☯ Trace Fields: Used to show the path taken by mail as it was transported.

In addition, the format allows other, user-defined fields to be specified, as long as they

correspond to the standard “<header name>: <header value>” syntax. This can be used to

provide additional information of various sorts. For example, sometimes the e-mail client

software will include a header line indicating the name and version of the software used to

compose and send the message. We'll also see that MIME uses new header lines to

encode information about MIME messages.

Key Concept: Each RFC 822 message begins with a set of headers that carry

essential information about the message. These headers are used to manage how

the message is processed and interpreted, and also describe the contents of the

message body. Each header consists of a header name and a header value. There are over

a dozen different standard RFC 822 headers, which are organized into groups; it is also

possible for customized user headers to be defined.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1393 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

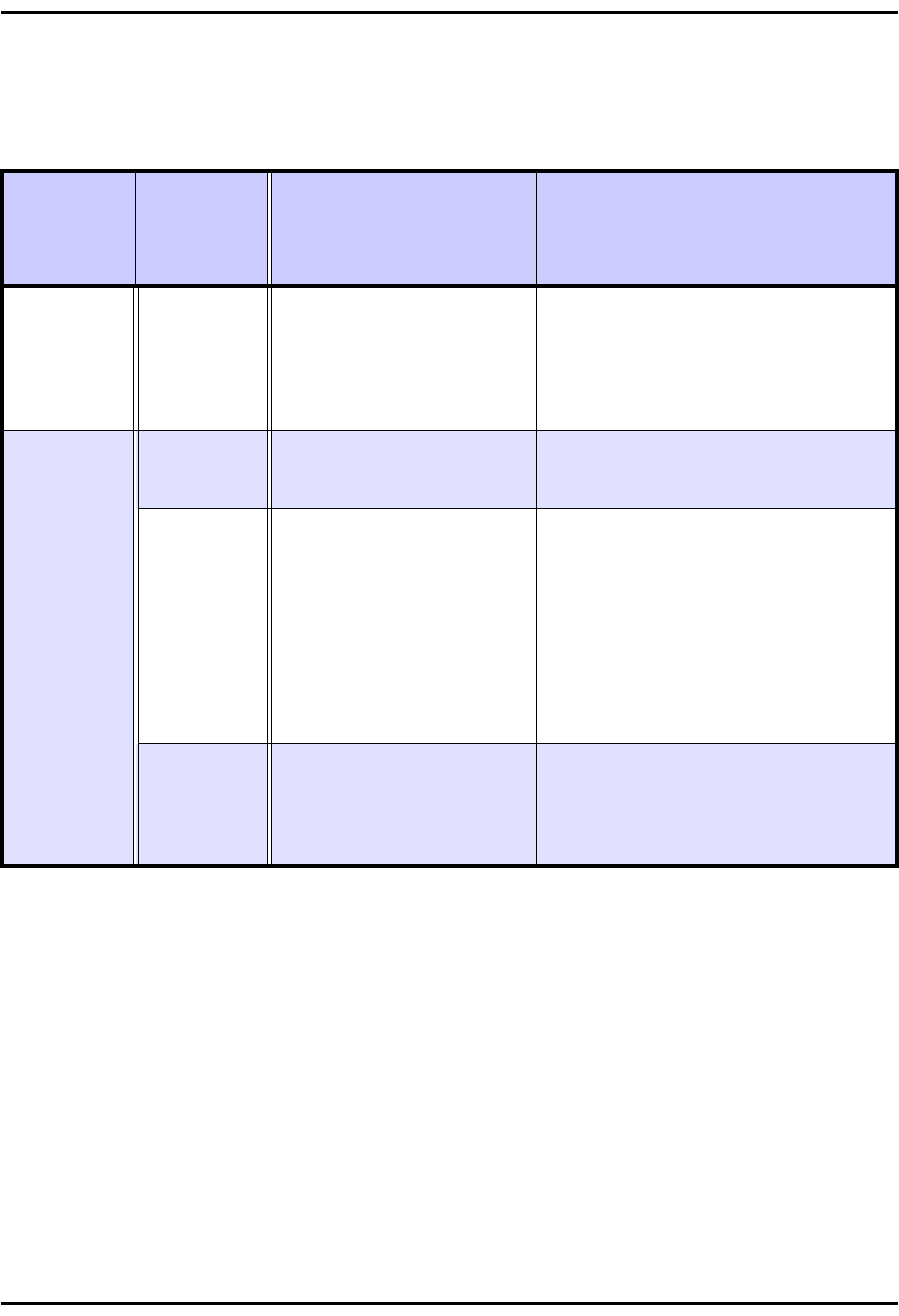

Common Header Field Groups and Header Fields

Table 241 describes the header fields in TCP/IP e-mail messages and how they are used:

Table 241: RFC 822 Electronic Mail Header Field Groups and Fields (Page 1 of 3)

Field Group Field Name Appearance

Number of

Occur-

rences Per

Message

Description

Origination

Date

Date: Mandatory 1

Indicates the date and time that the

message was made available for delivery

by the mail transport system. This is

commonly the date/time that the user tells

his or her e-mail client to send the

message.

Originator

Fields

From: Mandatory 1

The e-mail address of the user sending

the message. This should be the person

who was the source of the message itself.

Sender: Optional 1

The e-mail address of the person who is

sending the electronic mail, if different

from the message originator. For

example, if person B is sending an e-mail

containing a message from person A on

A's behalf, person A's address goes in the

From: header and person B's in the

Sender: header. If the originator and the

sender are the same (which is commonly

the case), this field is not present.

Reply-To: Optional 1

Used to tell the recipient of this message

the address the originator would like the

recipient to use for replies. If absent,

replies are normally sent back to the

From: address.

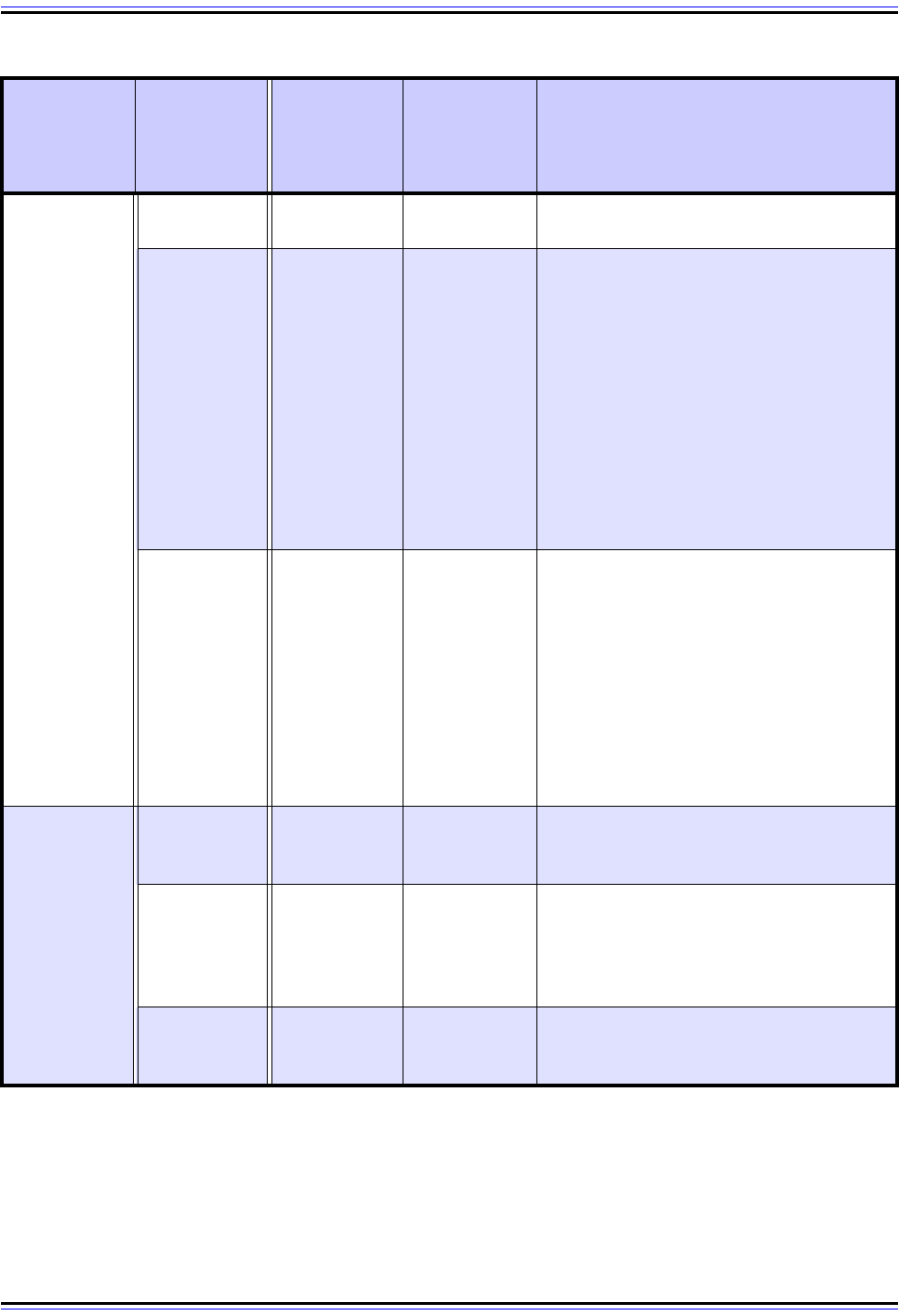

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1394 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Destination

Address

Field

To:

Normally

present

1

A list of primary recipients of the

message.

Cc: Optional 1

A list of recipients to receive a “copy” of

the message (“cc” stands for “carbon

copy”, as used in old typewriters). There

is no technical difference between how a

message is sent to someone listed in the

Cc: header and someone in the To:

header. The difference is only semantic, in

how the recipient interprets the message.

Someone in the To: list is usually the

person who is the direct object of the

message, while someone in the Cc: list is

being copied on the message for informa-

tional purposes.

Bcc: Optional 1

Contains a list of recipients to receive a

“blind carbon copy”. These people receive

a copy of the message without other

recipients knowing they have received it.

For example, if X is specified in the To:

line, Y is in the Cc: line, and Z is in the

Bcc: line, all three would get a copy of the

message, but X and Y would not know Z

had received a copy. This is done either

by removing the Bcc: line before message

delivery or altering its contents.

Identifi-

cation Fields

Message-ID:

Should be

present

1

Provides a unique code for identifying a

message; normally generated when a

message is sent.

In-Reply-To:

Optional,

normally

present for

replies

1

When a message is sent in reply to

another, the Message-ID: field of the

original message is specified in this field,

to tell the recipient of the reply what

original message the reply pertains to.

References: Optional 1

Identifies other documents related to this

message, such as other e-mail

messages.

Table 241: RFC 822 Electronic Mail Header Field Groups and Fields (Page 2 of 3)

Field Group Field Name Appearance

Number of

Occur-

rences Per

Message

Description

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1395 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

TCP/IP Electronic Mail RFC 822 Standard Message Format Processing and

Interpretation

The standards that define SMTP describe the protocol as being responsible for transporting

mail objects. A mail object is described as consisting of two components: a message and

an envelope. The envelope contains all the information necessary to accomplish transport

of the message; the message is everything in the e-mail message we have seen in the last

two topics, including both message header and body.

The distinction between these is important technically. Just as the postal service only looks

at the envelope and not its contents in determining what to do with a letter—no wise-cracks,

please! ☺—SMTP likewise only looks at the envelope in deciding how to send a message.

It does not rely on the information in the actual message itself for basic transport purposes.

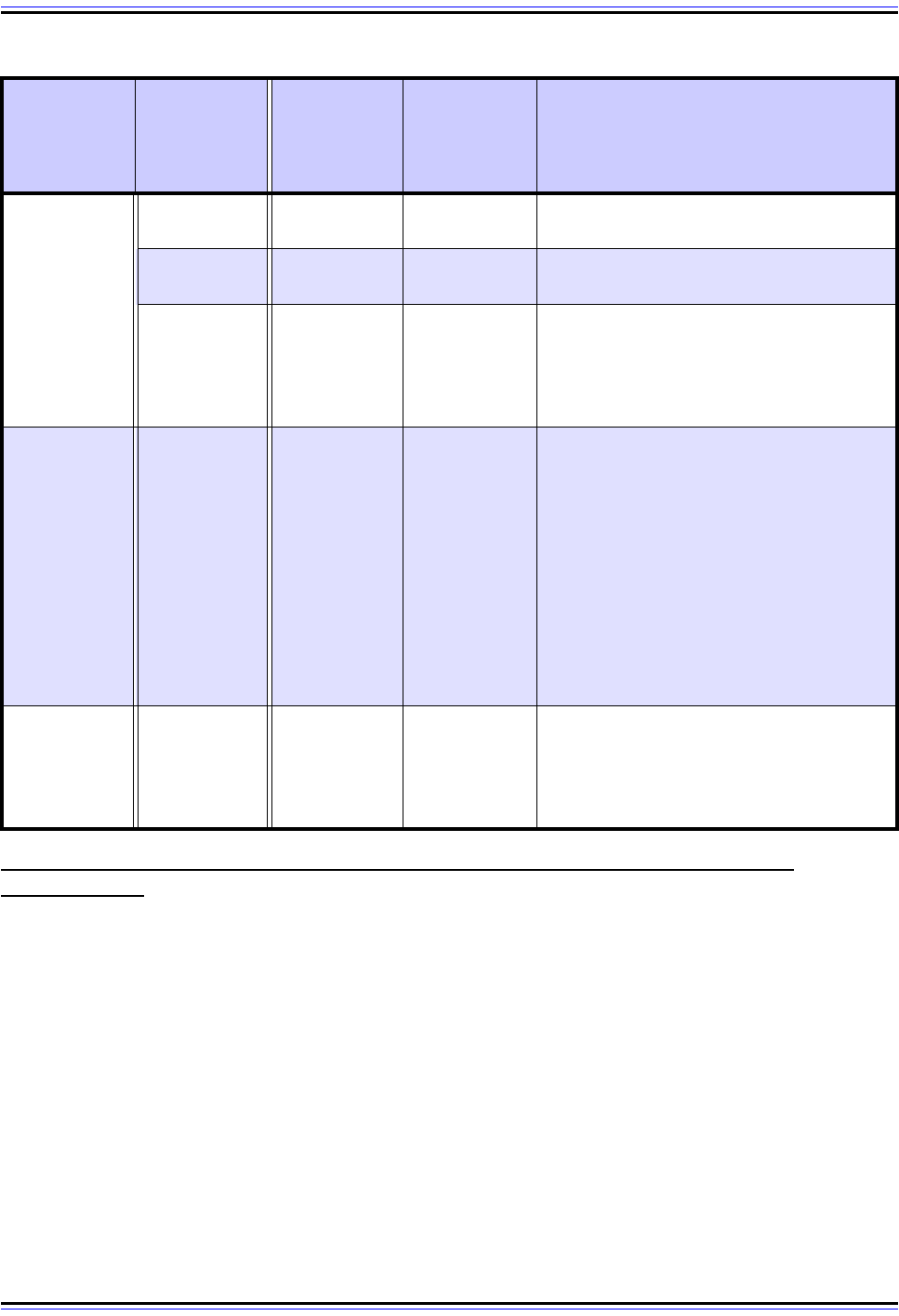

Informa-

tional Fields

Subject:

Normally

present

1

Describes the subject or topic of the

message.

Comments: Optional Unlimited

Contains summarized comments about

the message.

Keywords: Optional Unlimited

Contains a list of comma-separated

keywords that may be of use to the

recipient. This may be used optionally

when searching for messages on a

particular subject matter.

Resent

Fields

Resent-Date:

Resent-

From:

Resent-

Sender:

Resent-To:

Resent-Cc:

Resent-Bcc:

Resent-

Message-ID:

Each time a

message is

resent, a

resent block is

required

For each

resent block,

Resent-Date:

and Resent-

Sender: are

required; the

others are

optional

These are special fields used only when a

message is re-sent by the original

recipient to someone else, a process

called forwarding. For example, person X

may send a message to Y, who forwards it

to Z. In that case, the original Date:, From:

and other headers are as they were when

X sent the message. The Resent-Date:,

Resent-From: and other “resent” headers

are used to indicate the date, originator,

recipient and other characteristics of the

re-sent message.

Trace Fields

Received:

Return-Path:

Inserted by e-

mail system

Unlimited

These fields are inserted by computers as

they process a message and transport it

from the originator to the recipient. They

can be used to trace the path a message

took through the electronic mail system.

Table 241: RFC 822 Electronic Mail Header Field Groups and Fields (Page 3 of 3)

Field Group Field Name Appearance

Number of

Occur-

rences Per

Message

Description

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1396 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

So technically, the envelope is not the same as the message headers. However, as you can

tell by looking at the list of e-mail headers, each message includes the recipients and other

information needed for mail transport anyway. For this reason, it is typical for an e-mail

message to be specified with sufficient header information that it can be considered enough

by itself to accomplish its own delivery. E-mail software can process and interpret the

message to construct the necessary “envelope” for SMTP to transport the message to its

destination mailbox(es). The distinction between an e-mail message and its envelope is

discussed in more detail in the topic describing SMTP mail transfers.

RFC 822 Message Processing Sequence

The processing of RFC 822 messages is relatively straight-forward, due again to the simple

RFC 822 message format. The creation of the complete e-mail message begins with the

creation of a message body and certain headers by the user creating the message.

Whenever a message is “handled” by a software program, the headers are examined so

the program can determine what to do with it. Additional headers are also added and

changed as needed.

The following is the sequence of events that occur in the “lifetime” of a message's headers.

Composition

The human composer of the message writes the message body, and also tells the e-mail

client program the values to use for certain important header fields. These include the

intended recipients, the message subject and other informational fields, and certain optional

headers such as the Reply-To field.

Sender Client Processing

The e-mail client processes the message, puts the information the human provided into the

appropriate header form and creates the initial e-mail message. At this time, it inserts

certain headers into the message, such as the origination date. The client also parses the

intended recipient list to create the envelope for transmission of the message using SMTP.

SMTP Server Processing

SMTP servers do not pay attention to most of the fields in a message as they forward it.

They will, however, add certain headers, especially trace headers such as Received and

Return-Path, as they transport the message. These are generally prepended to the

beginning of the message in order to ensure that existing headers are not rearranged or

modified.

Note however that when gatewaying is done between e-mail systems, certain headers must

actually be changed, to ensure that the message is compatible with non-TCP/IP e-mail

software.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1397 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Recipient Client Processing

When the message arrives at its destination, the recipient's SMTP server may add headers

to indicate the date and time the message was received.

Recipient Access

When the recipient of a message uses client software, optionally via a mail access protocol

such as POP3 or IMAP, the software analyzes each message in the mailbox. This enables

the software to display the messages in a way meaningful to the human user, and may also

permit the selection of particular messages to be retrieved.

For example, most of us like to see a summary list of newly-received mail, showing the

originator, message subject and the date and time the message was received, so we can

decide which mail we want to read first, what mail to defer to a later time, and what to just

delete without reading (spam spam spam … ☺)

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1398 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

TCP/IP Enhanced Electronic Mail Message Format: Multipurpose Internet Mail

Extensions (MIME)

The RFC 822 e-mail message format is the standard for the exchange of electronic mail in

TCP/IP internetworks. Its use of simple ASCII text makes it easy to create, process and

read e-mail messages, which has contributed to the success of e-mail as a worldwide

communication method.

Unfortunately, while ASCII text is great for writing simple memorandums and other short

messages, it provides no flexibility to support other types of communication. To allow e-mail

to carry multimedia information, arbitrary files, and messages in languages using character

sets other than ASCII, the Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) standard was

created.

In this section I describe MIME and how it is used for modern e-mail messaging. I begin

with an overview of MIME and discussion of its history and the standards that define it. I

describe the two overall MIME message structures and provide a summary of the important

MIME-specific headers. I then explain the important MIME Content-Type header in more

detail, and discuss MIME discrete media types, subtypes and parameters. I discuss the

more complex MIME multipart and encapsulated message structures, and then the different

methods by which data can be encoded into MIME message bodies. I conclude with the

special MIME extension to allow support for non-ASCII characters in ordinary e-mail

headers.

Background Information: MIME is a message format that augments the basic

RFC 822 message format, rather than replacing it. This section assumes that you

have basic familiarity with the RFC 822 format and the more important e-mail

message headers.

Note: While MIME was developed specifically for mail, its encoding and data

representation methods have proven so useful that it has been adopted by other

application protocols as well. One of the best known of these is the HyperText

Transfer Protocol (HTTP), which uses MIME headers for indicating the characteristics of

data being transferred. Some elements of MIME were in fact developed not for e-mail but

for use by HTTP or other protocols, and I indicate this where appropriate. Be aware,

however, that HTTP only uses elements of MIME; there are important differences, and

HTTP messages are not MIME-compliant.

MIME Message Format Overview, Motivation, History and Standards

I describe the reasons why universal standards are important in the Networking Funda-

mentals chapter of this Guide, and re-emphasize the point in many other places as well.

Most protocols become successful for the specific reason that they are based on open

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1399 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

standards that are widely accepted. The RFC 822 e-mail message format standard is an

excellent example; it is used by millions of people every day to send and receive TCP/IP e-

mail.

However, success of standards comes at a price: reliance on those standards. Once a

standard is in wide use, it is very difficult to modify it, even when times change and those

standards are no longer sufficient for the requirements of modern computing. Again here,

unfortunately, the RFC 822 e-mail message format is an excellent example.

The Motivation for MIME

TCP/IP e-mail was developed in the 1960s and 1970s. Compared to the way the world of

computers and networking is today, almost everything back then was small. The networks

were small; the number of users was small; the computing capabilities of networked hosts

was small; the capacity of network connections was small; the number of network applica-

tions was small. (The only thing that wasn't small back then was the size of the computers

themselves!)

As a result of this, the requirements for electronic mail messaging were also rather… small.

Most computer input and output back then was text-based, and it was therefore natural that

the creators of SMTP and the RFC 822 standard would have envisioned e-mail as being

strictly a text medium. Accordingly, they specified RFC 822 to carry text messages.

The fledgling Internet was also developed within the United States, and at first, the entire

internetwork was within American borders. Most people in the United States speak English,

a language that as you may know uses a relatively small number of characters that is well-

represented using the ASCII character set. Defining the e-mail message format to support

United States ASCII (US-ASCII) also made sense at the time.

However, as computers developed, they moved away from a strict text model towards

graphical operating systems. And predictably, users became interested in sending more

than just text. They wanted to be able to transmit diagrams, non-ASCII text documents

(such as Microsoft Word files), binary program files, and eventually multimedia information:

digital photographs, MP3 audio clips, slide presentations, movie files and much more. Also,

as the Internet grew and became global, other countries came “online”, some of which used

languages that simply could not be expressed with the US-ASCII character set.

Unfortunately, by this point, the die was cast. RFC 822 was in wide use and changing it

would have also meant changes to how protocols such as SMTP, POP and IMAP worked,

protocols that ran on millions of machines. Yet by the late 1980s, it was quite clear that the

limitations of plain ASCII e-mail were a big problem that had to be resolved. A solution was

needed, and it came in the form of the Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME).

Note: MIME is usually referred to in the singular, as I will do from here forward,

even though it is an abbreviation of a plural term.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 1400 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

MIME Capabilities

The idea behind MIME is both clever and elegant—which means I like it! RFC 822 restricts

e-mail messages to be ASCII text, but that doesn't mean that we cannot define a more

specific structure for how that ASCII text is created. Instead of just letting the user type an

ASCII text message, we can use ASCII text characters to actually encode non-text infor-

mation (commonly called attachments). Using this technique, MIME allows regular RFC

822 e-mail messages to carry the following:

☯ Non-text information, including graphic files, multimedia clips and all the other non-text

data examples I listed earlier;

☯ Arbitrary binary files, including executable programs and files stored in proprietary

formats (for example, AutoCAD files, Adobe Acrobat PDF files and so forth);

☯ Text messages that use character sets other than ASCII. This even includes the ability

to use non-ASCII characters in the headers of RFC 822 e-mail messages.

MIME even goes one step beyond this, by actually defining a structure that allows multiple

files to be encoded into a single e-mail message, including files of different types. For

example, someone working on a budget analysis could send one e-mail message that

includes a text message, a Powerpoint presentation, and a spreadsheet containing the

budget figures. This capability has greatly expanded e-mail’s usefulness in TCP/IP.

All of this is accomplished through special encoding rules that transform non-ASCII files

and information into an ASCII form. Headers are added to the message to indicate how the

information is encoded. The encoded message can then be sent through the system like

any other message. SMTP and the other protocols that handle mail pay no attention to the

message body, so they don't even know MIME has been used.

The only changes required to the e-mail software is adding support for MIME to e-mail client

programs: both the sender and receiver must support MIME to encode and decode the

messages. Support for MIME was not widespread when MIME was first developed, but the

value of the technique is so significant that it is present in nearly all e-mail client software

today. Furthermore, most clients today can also use the information in MIME headers to not

only decode non-text information but pass it to the appropriate application for presentation

to the user.

Key Concept: The use of the RFC 822 message format ensures that all devices are

able to read each other’s e-mail messages, but it has a critical limitation: it only

supports plain, ASCII text. This is insufficient for the needs of modern internetworks,

yet reliance on the RFC 822 standard would have made replacing it difficult. Instead, a new

standard called the Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) was defined. MIME

specifies several methods that allow e-mail messages to contain multimedia content, binary

files, and text files using non-ASCII character sets, all while still adhering to the RFC 822

message format. MIME also further expands e-mail’s flexibility by allowing multiple files or

pieces of content to be sent in a single message.