Camp J. The Archaeology of Athens

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Just south of the marsh is a medieval tower in which were found several marble column

drums and an Ionic capital datable to the early fifth century

B

.

C

., with cuttings to carry

sculpture on top. This almost certainly is the trophy, set up at the turning point (trope) of the

battle, where the enemy suffered the greatest number of casualties. It was a source of great

pride to the Athenians, and a number of ancient writers refer to it, describing it as a column

of white marble. Several drums are now missing, but it is possible to estimate the original

height at more than 10 meters.

Another burial associated with the battle is more controversial. In the late 1960s a tu-

mulus (burial mound) was found near the museum at Vrana. Half of it was excavated, pro-

ducing eleven graves, all dated to the early fifth century

B

.

C

. and all males. One man was

aged between thirty and forty, and there was a boy of about ten; the rest were all in their

twenties. The suggestion has been made that this was the tomb of the Athenian allies, the

Plataians, who fought at Marathon and were also buried on the field of battle, as recorded

by Pausanias (1.32.3):

48 EARLY AND ARCHAIC ATHENS

50

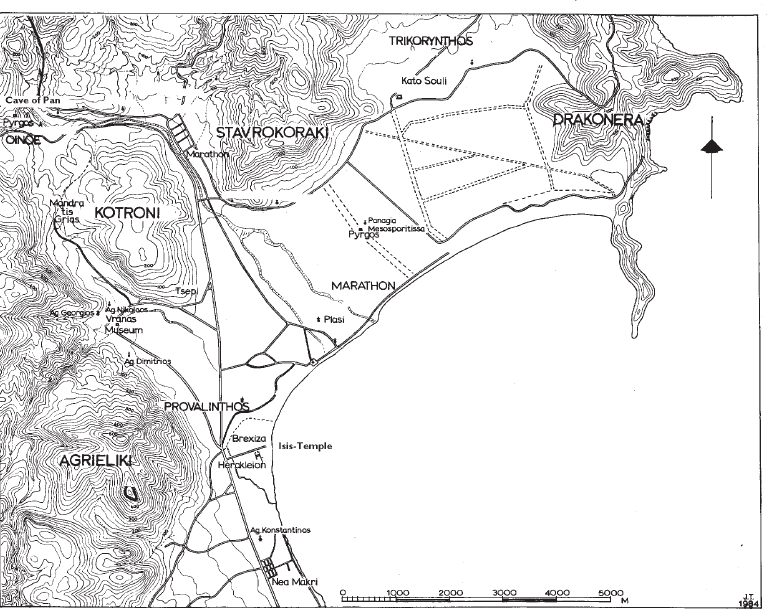

47. Map of the plain of Marathon.

In the plain is the grave of the Athenians,

and over it are tombstones with the names

of the fallen arranged according to tribes.

There is another grave for the Boiotians of Plataia and the slaves; for slaves

fought then for the first time. There is a separate tomb for Miltiades, son of

Kimon.

Against the identification is the location of the tomb, 2.5 kilometers from the soros and the

battlefield, and the fact that none of the skeletons show signs of wounds. In addition, the

tumulus covers eleven individual graves, whereas in most military multiple graves (polyan-

dreia) the bodies were all neatly laid out in rows, like sardines in a tin: at Thespiai (424

B

.

C

.),

in the Kerameikos at Athens (403

B

.

C

.), and at Chaironeia (338

B

.

C

.). Finally, two nine-

The Persian Wars 49

51

Above 48. The soros, or burial mound, of the Athenian

dead at Marathon, 490 b.c.

Left 49. Bronze helmet dedicated by Miltiades at

Olympia after the Battle of Marathon.

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

teenth-century travelers, Leake and

Clarke, each saw a second, smaller tu-

mulus near the soros during their vis-

its to Marathon. The location of the

tomb of the Plataians, therefore, re-

mains an open question.

Various deities were worshiped after the battle in thanks for the help they were

thought to have provided. In particular, the horned, goat-footed god of Arcadia, Pan, re-

ceived special attention, according to a story in Herodotos (6.105):

The generals sent as a herald to Sparta Pheidippides, an Athenian, one who was

a runner of long distances and made that his career. This man, as he said him-

self and told the Athenians, when he was on Mount Parthenian above Tegea met

Pan, who calling Pheidippides by name told him to say to the Athenians, “Why

do you take no thought of me, who is your friend, has been before, and will be

again?” This story the Athenians believed and when they succeeded, they

founded a sanctuary of Pan below the Acropolis and sought the god’s favor with

yearly sacrifices and torch races.

According to both Pausanias and Lucian, Pan’s sanctuary was on the northwest slopes of

the Acropolis. It is associated with one of the shallow caves there which have rock-cut

niches designed to receive votive reliefs, several of which were found lower down on the

slopes (see fig. 112). This sanctuary was not an isolated phenomenon; other caves through-

out Attica show signs of cult activity in honor of Pan, all beginning in the first half of the

fifth century

B

.

C

. Evidence for his worship takes the form of inscriptions, votive plaques in

marble, and terra-cotta statuettes of the god and his companions, the nymphs.

One of the most impressive caves, only partially excavated, is located at Oinoe near

Marathon itself. Other caves sacred to Pan and the nymphs have been found on Mounts

Parnes, Pentele, Hymettos, and Aigaleos, as well as at Eleusis. The cave on Hymettos is the

most ornate. A man from Thera (Santorini) by the name of Archedemos, who described

himself as a nympholept (one seized by the nymphs), covered the walls of the cave with re-

liefs and dedicatory inscriptions. Miltiades also dedicated a statue of Pan at Marathon; the

dedicatory inscription on the base is said to have been composed by Simonides (Anth. Pal.

16.232):

50 EARLY AND ARCHAIC ATHENS

50. Ionic marble column capital of the

trophy for the Battle of Marathon.

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

Miltiades erected me, goat-footed Pan, the Arcadian, the foe of the Medes, the

friend of the Athenians.

Herakles had already been popular in Athens for years, showing up on numerous

black-figured pots and, as noted, on several of the sculptural groups on the sixth-century

Acropolis. He had a particular association with Marathon, however; the spring there called

Makaria was named after his daughter, and the people of Marathon claimed to have been

the first to worship him as a god. When they marched out to confront the Persians, the

The Persian Wars 51

51. The “tomb of the Plataians” at Vrana (Marathon), early 5th century b.c.

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

Athenians camped in Herakles’ sanctuary at Marathon before the battle, and after the vic-

tory they instituted special games in his honor. Two fifth-century inscriptions found not far

from each other allow us to identify the general area of his sanctuary at the south end of the

plain.

In Athens a new temple was laid out to house Athena on the Acropolis. Unlike the

two sixth-century limestone temples, this one was to be of Pentelic marble and represents

the earliest substantial exploitation of the quarries on Mount Pentele. Before this, when

marble was required, the Athenians imported it from the Cycladic islands of Naxos and

Paros. A huge platform of limestone was constructed south of the old temple of Athena

(on the site of the future Parthenon), and large blocks and drums of marble were hauled

up the hill. Several dozen column drums were brought up and put in place, but, as a result

of the continuing war with Persia, the building was never finished. Although no ancient

source specifies the connection, it has been generally accepted that this predecessor to the

Parthenon was started soon after 490

B

.

C

. and was intended to commemorate the victory

at Marathon.

A fragmentary inscription of the year 485/4 provides some information about the

Acropolis at this time, though its interpretation is uncertain (IG I

3

4B). It consists of a se-

ries of regulations about what may not be done up there, such as lighting fires and dump-

ing dung. The areas where these things may not take place are defined by monuments:

around or between the temple, the altar, the Kekropion (grave or sanctuary of Kekrops), and

a structure—perhaps a temple—known as the Hekatompedon. The word hekatompedon

(100-footer) is often used to describe a large temple, though some think it may simply refer

to a part of the Acropolis. The inscription also refers to oikemata (rooms or structures) in

the Hekatompedon, which treasurers are to open every ten days to ensure that the treasure

kept therein is safe. The inscription is carved on a reused metope (part of the frieze) of the

mid-sixth-century temple, so we know that the early limestone temple with lion and bulls

(see figs. 25, 26) had been dismantled by the mid-480s, presumably to make way for a new

temple. Unfortunately, it is not clear which temple succeeded it, the one with the marble gi-

gantomachy built around 510–500 on the foundations south of the Erechtheion (see figs.

40, 41) or the marble temple started after 490 on the site later occupied by the Parthenon.

Several years later the Athenians added a colossal bronze statue of a fully armed

Athena Promachos (Champion) to the Acropolis. A work of the sculptor Pheidias, it was

paid for with the spoils from Marathon, according to Pausanias (1.28.2). It stood just inside

the gateway, and Pausanias tells us it was so large that

the head of the spear and the crest of the helmet of this Athena are visible to

mariners sailing from Sounion to Athens.

52 EARLY AND ARCHAIC ATHENS

52

53

54

Representations of the statue are found on

Athenian lamps and coins of the Roman period;

the statue itself was carried off to adorn Con-

stantinople in the fifth century

A

.

D

. and was

eventually destroyed in the early thirteenth cen-

tury. A Byzantine writer, Niketas Choniates (738

B), describes the statue as he saw it in the forum

of Constantine, before its destruction:

In stature it rose to the height of about 30

feet, and was clothed in garments of the

The Persian Wars 53

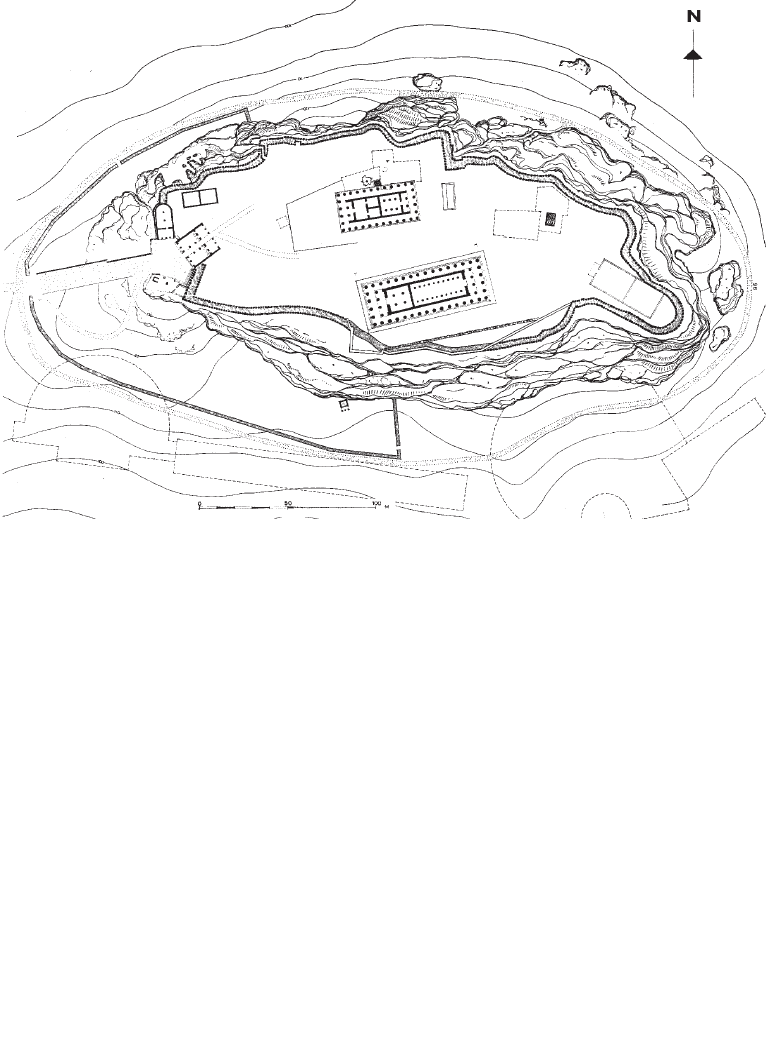

52. Plan of the Acropolis, ca. 480 b.c., with the old temple of Athena at the top (north) and the

predecessor to the Parthenon (unfinished) at the bottom (south).

53. Unf luted marble Doric column drum from the

unfinished predecessor of the Parthenon,

490–480 b.c.

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

54. The Acropolis as it would have appeared in 480 b.c., with the old temple of Athena (ca. 510–500

b.c.) on the left and the half-finished older Parthenon (started ca. 490 b.c.) on the right. (Watercolor by

Peter Connolly)

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

same material as the whole statue, namely, of bronze. The robe reached to the

feet and was gathered up in several places. A warrior’s baldric passed round

her waist and clasped it tightly. Over her prominent breasts she wore a cun-

ningly wrought garment, like an aegis, suspended from her shoulders, and

representing the Gorgon’s head. Her neck, which was undraped and of great

length, was a sight to cause unrestrained delight. Her veins stood out promi-

nently, and her whole frame was supple and, where needed, well-jointed.

Upon her head a crest of horsehair “nodded fearfully from above.” Her hair

was twisted in a braid and fastened at the back, while that which streamed

from her forehead was a feast for the eyes; for it was not altogether concealed

by the helmet, which allowed a glimpse of her tresses to be seen. Her left hand

held up the folds of her dress, while the right was extended toward the south

and supported her head.

At Cape Sounion, the southernmost tip of Attica, a Doric temple was begun, in lime-

stone, dedicated to Poseidon. Its unfinished, unf luted column drums may be seen built

into the platform which surrounds the later Classical temple. At Rhamnous, just north of

Marathon, a small Doric temple with two columns on the front was built, while a huge

piece of Parian marble, said to have been brought by the Persians in the confident certainty

that it would be made into a trophy, was eventually carved by the sculptor Agorakritos into

a statue of Nemesis. And at Apollo’s sanctuary in Delphi, the victory of Marathon was com-

memorated by the Athenians with the construction of a marble treasury decorated with

sculpted scenes of the labors of Herakles and Theseus. In addition, bronze statues depict-

ing Athena, Apollo, several early Athenian kings, and the general Miltiades were set up on

the sacred way in the sanctuary.

The appearance of Hippias with the Persian army at Marathon made the Athenians

extremely nervous. They had become accustomed to their democratic form of government,

and the possibility of a renewed tyranny was distasteful. Statues of Harmodios and Aristo-

geiton, the slayers of Hipparchos, had been set up in the Agora soon after Hippias’ depar-

ture, and the two were worshiped as the Tyrannicides—a personal feud quickly taking on

the guise of political heroism, according to Thucydides. Soon after Marathon, therefore, a

new procedure, known as ostracism, was instituted. Once a year all the citizens gathered in

the Agora and voted on a simple question: was anyone in the city becoming so powerful

that he represented a threat to the democracy? If a majority voted yes, then the Athenians

met two months later, again in the Agora, each one bringing with him an ostrakon (pot-

sherd) on which he had scratched the name of the man whose power and inf luence were

The Persian Wars 55

too great. The man with the most

votes was exiled for ten years. Early

in the fifth century most of Athens’

leading statesmen took this en-

forced vacation at one time or another. The ballots, useless immediately after the vote, were

used to fill potholes in roadways and the like, and close to ten thousand of them have been

found in the excavations of the Agora and the Kerameikos.

At first the ostracisms were aimed at friends and supporters of the Peisistratids, but

soon they became a weapon in the arsenal of skilled politicians. The first man to be ostra-

cized who was not a friend to tyranny was Xanthippos, the father of Perikles, in 484. His op-

ponent seems to have been Themistokles, one of the most astute and effective leaders of

early Athens. Convinced that the victory at Marathon did not mean the end of the Persian

threat, Themistokles championed a long-term policy to turn Athens into a naval power. He

fortified the Peiraieus and persuaded the Athenians to build a huge f leet. Thucydides de-

scribes the Themistoklean wall of the Peiraieus (1.93):

Following his advice they built the wall around the Peiraieus of the thickness

that may still be observed; for two wagons carrying the stones could meet and

pass each other. Inside, moreover, there was neither rubble nor clay but stones

of large size hewn square were laid together, bound to one another on the out-

side with iron clamps and lead.

The line of this early wall has been recognized, though most of what survives today is dated

to later rebuilding. In 484/3

B

.

C

. a large deposit of silver was found in the mining district of

Laureion in south Attica. The public revenues of this discovery amounted to some two hun-

dred talents, a huge sum of money: 1.2 million drachmas at a time when the drachma was

worth roughly a day’s wage. At the urging of Themistokles, the Athenians did not distrib-

ute the money among themselves in the usual fashion but used it to build a f leet of two

hundred warships (triremes), a decision which made Athens the primary Greek naval

power in the Mediterranean. Intended for use against the neighboring island of Aigina,

these ships proved essential in the next phase of the Persian Wars.

The Persians, though thwarted at Marathon, did not abandon their plans for the con-

56 EARLY AND ARCHAIC ATHENS

55

55. A selection of ostraka cast against

Aristeides, Themistokles, Kimon, and

Perikles, 485–440 b.c.

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

quest of Athens and ten years later, in 480/79, they returned, led by King Xerxes himself,

this time with both a large f leet and a huge land army. After beating the Spartans and their

allies at the narrow pass of Thermopylai, the Persians broke into southern Greece. The

Athenians, faced with this vast army, took the decision to abandon Athens. Women, chil-

dren, and the elderly were transported to the island of Salamis and to Troizen in the Pelo-

ponnese, while the men manned the triremes, determined to oppose the Persians at sea.

The Persians occupied Athens, taking the citadel against only a token defense, plundered

the temples, and burnt the Acropolis. According to Herodotos and Thucydides, hardly a

building was left standing as the Persians sacked and burned the city in retaliation for the

destruction of Sardis in 498. Herodotos writes of the Persian general Mardonios,

He burnt Athens, and utterly overthrew and demolished whatever wall or house

or temple was left standing. (9.13)

Thucydides’ account is similar:

Of the encircling wall only small portions were left standing, and most of the

houses were in ruins, only a few remaining in which the chief men of the Per-

sians had themselves taken quarters. (1.89.3)

The archaeological record seems equally compelling. The temples and buildings which

adorned Athena’s sanctuary on the Acropolis were all destroyed: the old temple of Athena,

the unfinished marble predecessor of the Parthenon, the early temple of Athena Nike, and

the little treasury-like buildings. The dozens of korai and other statues now in the Acropo-

lis Museum all bear witness to the deliberate destruction of the sanctuary and its offerings,

and excavations have recovered numerous small fragments of high-quality red- and black-

figured pottery, dedicated to Athena, showing clear signs of the effect of the fire.

Excavations in the Agora and elsewhere also attest to the almost complete destruc-

tion of the lower city. Seventeen wells excavated in the Agora were filled with the debris

from the private houses they once supplied with water, and all of the Archaic public build-

ings show signs of grave damage. Works of art were carried off: the statues of the Tyranni-

cides to Susa (Arrian, Anabasis 3.16.8) and a bronze statue of a water bearer commissioned

by Themistokles to Sardis (Plutarch, Themistokles 31.1). The clear break seen in Greek art

between the Archaic and Classical periods is punctuated in Athens by the total devastation

of the city, requiring a completely new start in 479/8.

The devastation extended to Attica as well. The small Archaic temple at Rhamnous,

the unfinished temple of Poseidon at Sounion, and the Telesterion at Eleusis were all de-

The Persian Wars 57