Camp J. The Archaeology of Athens

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

guess at the outset that these rich houses were the homes of the philosophers, sophists, and

other teachers, who were the aristocracy and the wealthy men of Roman Athens. As early as

the second century they were charging fees for their courses and using their houses as pri-

vate schools. Eunapius describes the house of the sophist Julian of Cappadocia early in the

fourth century:

The author himself saw Julian’s house at Athens; poor and humble as it was,

nevertheless from it breathed the fragrance of Hermes and the Muses, so

closely did it resemble a holy temple. This house he had bequeathed to Pro-

haeresius. There too were erected statues of the pupils whom he had most ad-

mired; and he had a theater of polished marble made after the model of a public

theater but smaller and of a size suitable to a house. For in those days, so bitter

228 LATE ROMAN ATHENS

222

222. Philosophical school, with arches and apsidal pool, 4th to 6th century a.d.

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

was the feud at Athens between the

citizens and the young students—as

if the city after those wars of hers

was festering within her walls the

peril of discord—that none of the

Sophists ventured to go down into

the city and discourse in public, but

they confined their utterances to

their private lecture theaters and

there discoursed to their students.

(Eunapius, Lives 483)

Eunapius refers to an important feature

of the schools at Athens: they were pagan

institutions. Established in the old gymna-

sia, their adherents worshiped Herakles,

Hermes, the Nymphs, and the Muses.

Even the official advent of Christianity un-

der Constantine in 325 seems to have had

minimal impact on the city. Athens re-

mained pagan until the end of antiquity.

In addition to the large houses of the fourth century, several Athenian baths show

signs of construction or renovation, and there is good evidence that the Attic lamp industry

was f lourishing, particularly in the area of the Kerameikos. Many of these lamps were ex-

ported all over Greece and farther afield, from Spain to South Russia; in Attica they begin to

appear in large numbers in the mountain caves of Pan, especially at Vari and on Mount

Parnes. These are the first of literally hundreds of lamps to be deposited in the two caves

during the fifth and sixth centuries. No convincing explanation has been put forth for this

intense interest in Pan or his caves after years of relative neglect. Elsewhere in Attica there

is little evidence of significant activity in the fourth century.

The theater of Dionysos also continued to be used in this period. The last substantial

stage, decorated with the reused sculpted frieze blocks of the second century

A

.

D

. (see fig.

201), carries a late dedicatory inscription:

Late Roman Athens 229

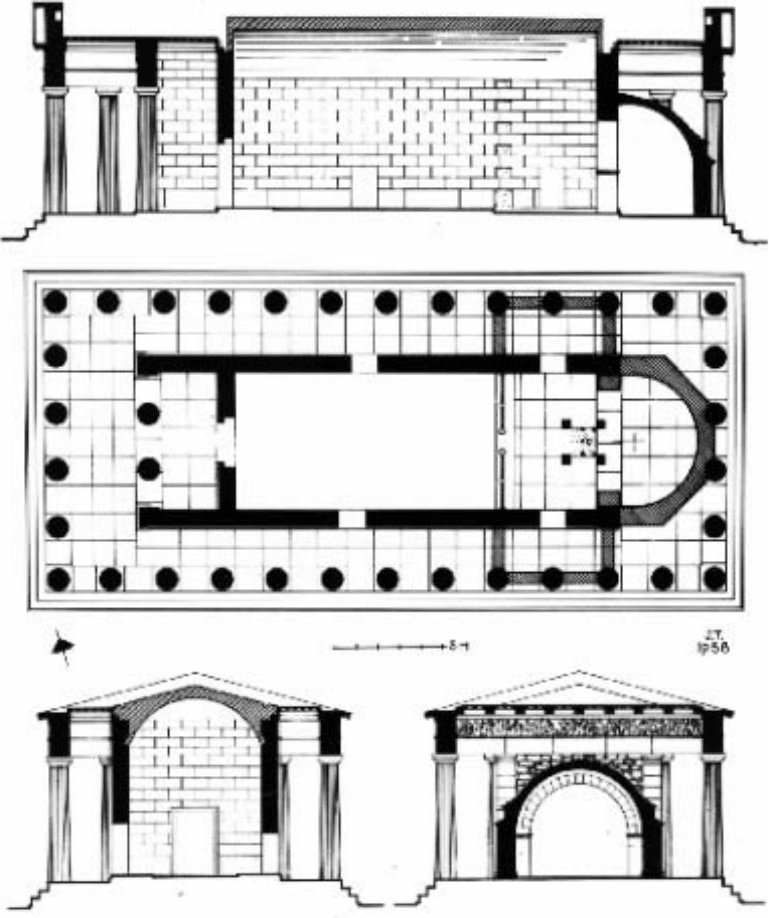

223

223. Youthful Herakles discarded down a well in

the philosophical school in the first half of the

6th century a.d.

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

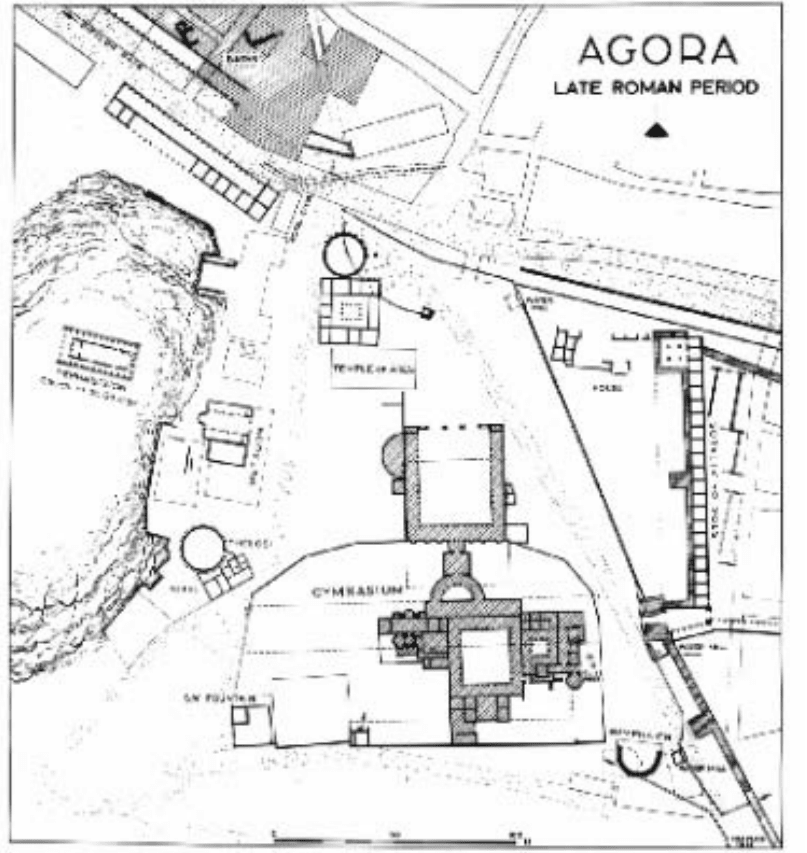

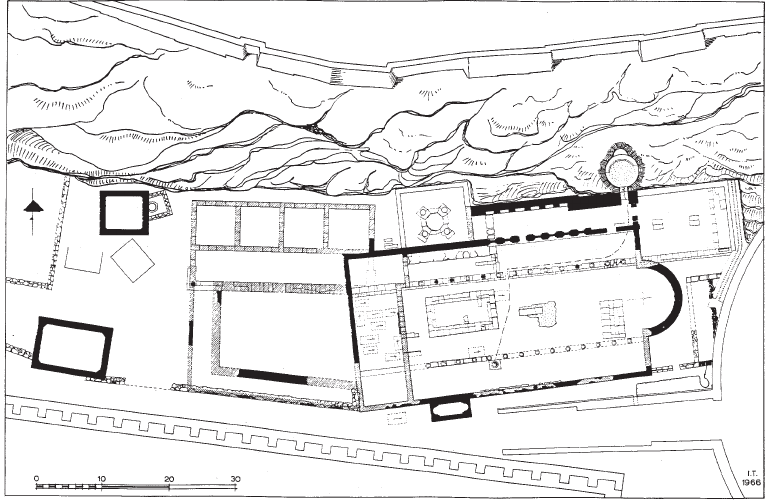

224. Plan of the Agora in the late Roman period, ca. 450 a.d., showing the post-Herulian wall at right

and the palace(?) in the center.

For you, lover of the sacred rites, this beautiful bema [speakers’ platform, stage]

has been built by Phaidros, son of Zoilos, archon of life-giving Athens. (IG II

2

5021)

The next danger to threaten the city came with Alaric and his Visigoths in 396. The

literary sources give two versions of his attack. Zosimus tells us that Athena and Achilles

appeared and so frightened Alaric that he made peace and withdrew, leaving Athens and

Attica unharmed. Claudian, Saint Jerome, and Philostorgius suggest, on the other hand,

that the city was taken. Not enough work has been done within the circuit of the post-Heru-

lian wall to allow us to assess the effect of Alaric’s visit. Outside the walls, however, in the

area of the old Agora and the Kerameikos, there are distinct signs of his unfriendly pres-

ence. Several of the Agora buildings on the west side which survived the Herulians in 267

(Tholos, Stoa of Zeus, Apollo Patroos) now show signs of damage. The bishop Synesios vis-

Late Roman Athens 231

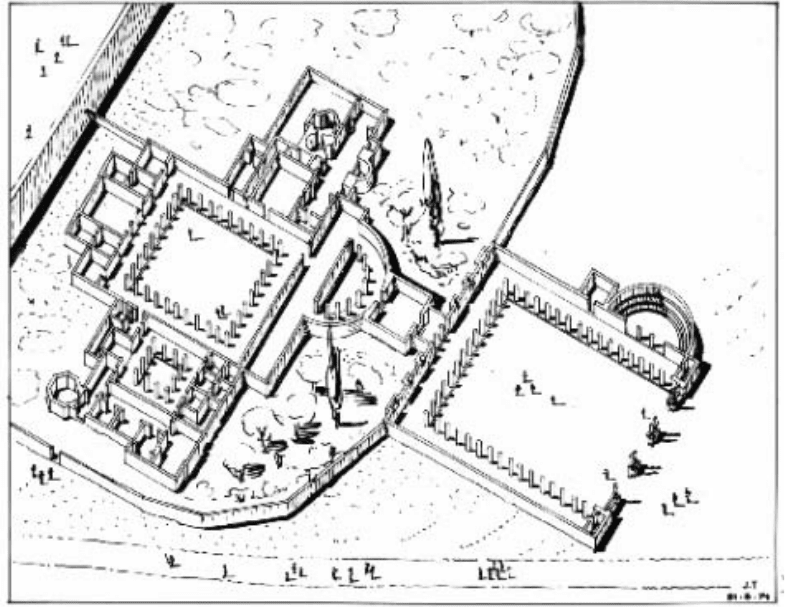

225. Late Roman complex (palace?) in the area of the Agora, ca. a.d. 420.

ited Athens soon afterward, between 395 and 399, and was not impressed with what he

saw: the Painted Stoa bereft of paintings and the philosophers of the city replaced by bee-

keepers. The Areopagos houses, on the other hand, continued to be occupied into the fifth

and sixth centuries, with no clear evidence of ill effects from Alaric’s visit. In Attica, the fi-

nal destruction of Eleusis is usually attributed to Alaric.

A revival of sorts can be dated to the first half of the fifth century. In the old Agora the

Hellenistic Metroon was partially refurbished and the third room from the south provided

with a mosaic f loor. The most impressive new construction was a huge complex covering

the old Odeion of Agrippa and most of the South Square. Its entrance was at the north,

where several of the old second-century giants and tritons (see fig. 212) were re-erected on

new high pedestals built of reused material. Behind them was a vast complex of court-

yards, rooms, octagonal and apsidal chambers, and a small bath. The date from pottery

and finds seems to be the first quarter of the fifth century. Its identification and function

are uncertain; it has the appearance of an elaborate villa, and perhaps served as an official

residence.

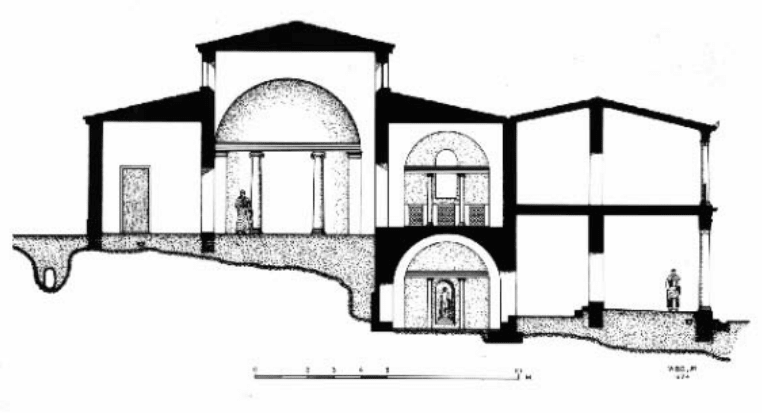

Just to the north a large square building of some 25 meters a side was built at about

the same time; it had a group of rooms set around a central courtyard. Another large com-

plex, also dated to the early fifth century, incorporated the old northern stoa of the Library

of Pantainos. It had two stories, with niches set in the walls, a small courtyard, and a small

232 LATE ROMAN ATHENS

224

225

226

226. Late Roman building over the Library of Pantainos, early 5th century a.d.

bathing complex; again, no evidence has been recovered to shed clear light on either the

function or identification of the building.

One of the individuals responsible for Athens in the early fifth century, and perhaps

for some of the renewal we have been noting, was Herculius, prefect of Illyria in 408–412.

For whatever reason, he was honored with statues, one on the Acropolis dedicated by the

Sophist Apronianos (IG II

2

4225) and a second erected near the west door of the Library of

Hadrian and dedicated by a certain Plutarch, who may have been one of the most promi-

nent philosophers or Sophists of the city. This same Plutarch, a pagan, was himself hon-

ored for paying on three occasions the costs of the Panathenaic ship, still making its voyage

to the Acropolis well into the fifth century.

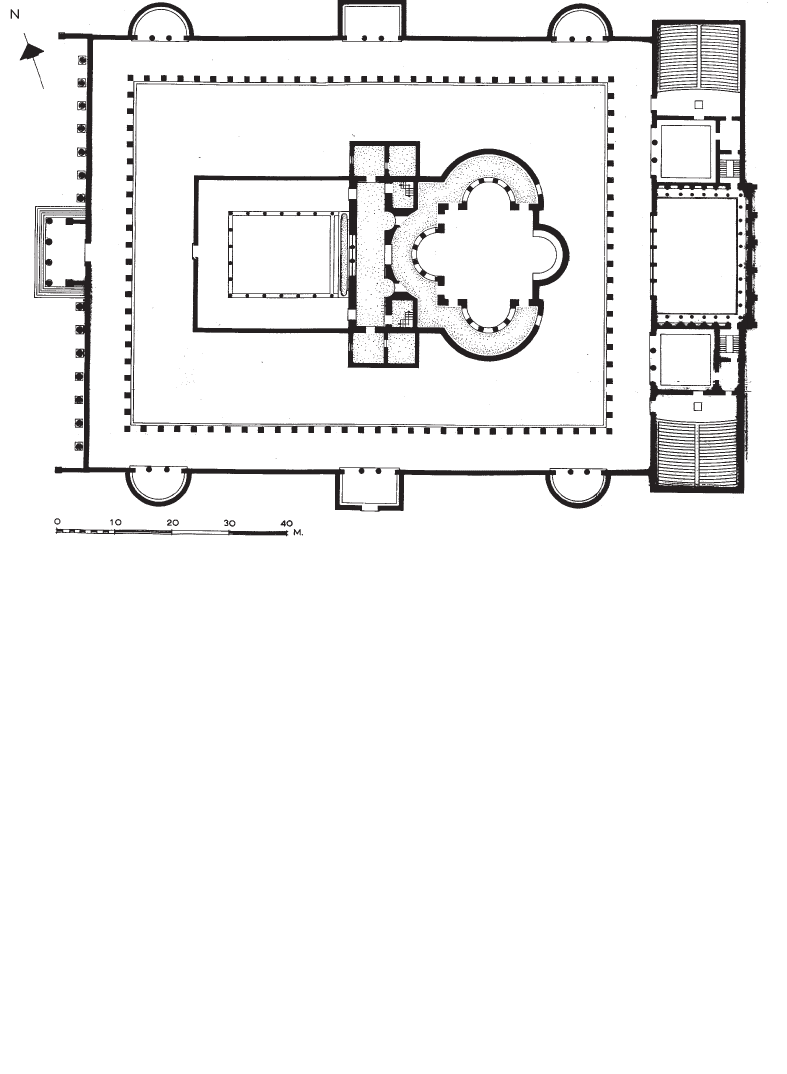

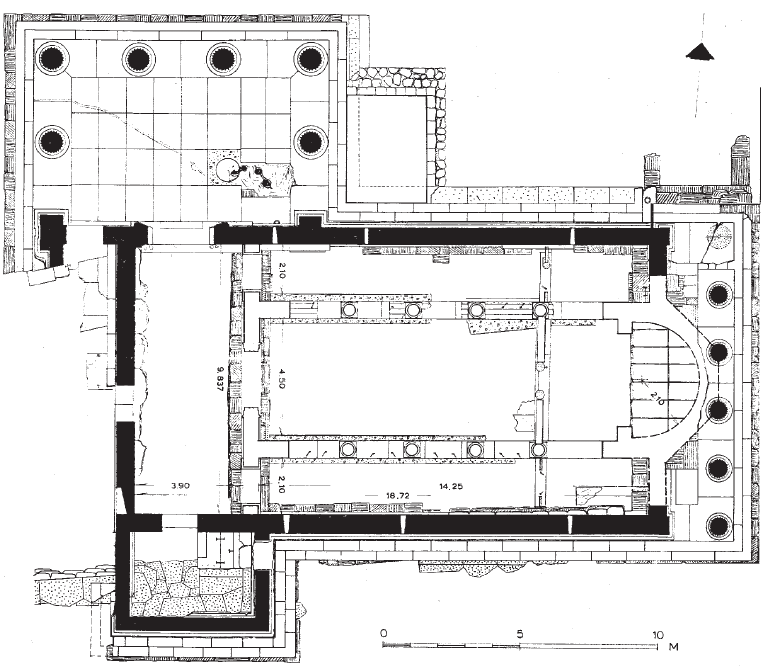

Within the confines of the old library we find the first substantive architectural evi-

dence of Christian activity, dated to the fifth century, closely following yet another attempt

to shut down the pagan sanctuaries, this time by Theodosius II in 435. This is a large build-

ing with four apses, all but the eastern apse set off by colonnades to form an ambulatory.

To the west, a broad hallway gives access to the structure through three doors. The simple

Late Roman Athens 233

227

227. Tetraconch (5th century a.d.) in the courtyard of the Library of Hadrian, with colonnade of later

church (7th century a.d.).

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

apse at the east and the presence

of a narthex and atrium at the

west now make it almost certain

that we have here a church, the

earliest yet known from Athens.

The date is based on the style of

234 LATE ROMAN ATHENS

229. Roman relief of Artemis,

disfigured by Christians in the 6th

century a.d., found in the pagan

philosophical school occupied by

Christians after 529. (Cf. figs. 220–

222)

228. Tetraconch in the Library of

Hadrian.

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

the mosaic f loors, which decorate the ambulatory and some of the western rooms. Though

dwarfed by its setting in the court of the old library, the “Tetraconch,” as it is sometimes

called, is a large building, measuring about 40 meters on a side, with the centralized plan

often favored for churches of this period.

The other common form of early Christian church, the long, three-aisled basilica,

makes its appearance slightly later in the fifth century. The first was built in southeast

Athens along the banks of the Ilissos River, where the remains can still be seen today. Sev-

eral other basilicas came to be built in the same general area thereafter. The conversion of

pagan temples to Christian use seems to be a late phenomenon in Athens, for the most part

dating to the sixth and seventh centuries. With the gradual rise of Christianity, numerous

fifth-century basilicas are also to be found throughout the countryside in Attica, often near

the old deme sites: Brauron (Philaidai), Porto Raphti (Steireia), and Eleusis.

A single sentence in Procopius (Bell. [Vand] 3.5.23) suggests that Greece was the vic-

tim of a Vandal incursion in the fifth century. A layer of ash and debris found along the west

side of the Agora seems to confirm this reference, as does a hoard of almost five hundred

Late Roman Athens 235

228

230. Plan of the early Christian basilica built over the remains of the Asklepieion, 6th century a.d.

(Cf. fig. 149)

231. Plan of the Hephaisteion as converted into a Christian church in the 7th century.

bronze coins, the latest dating to the reign of Leo I (457–474). Also during the second half

of the fifth century the great bronze statue of Athena Promachos, which had been a land-

mark on the Acropolis for centuries, was removed to Constantinople. It stood thereafter in

the Forum of Constantine until it was torn to pieces by drunken rioters in 1203.

The reign of the Christian emperor Justinian in Constantinople (527–565) in many

ways marks the end of ancient Athens. The old pagan schools of the city finally proved too

popular for their own good, more than five hundred years after the birth of Christ. In 529

Justinian issued a decree forbidding any pagan to teach philosophy in Athens. This, more

than any barbarian incursion, was the death knell of the city. With the closing of the schools

after more than nine hundred years, Athens began a decline into insignificance.

Late Roman Athens 237

232. The Erechtheion, as converted into a Christian basilica, 7th century.