Bulmer-Thomas V., Coatsworth J., Cortes-Conde R. The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America: Volume 2, The Long Twentieth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

622 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

in the age structure, triggered by the demographic transition, has a strong

association with the sharp rise in female participation rates. Thus, the aging

of Latin America’s population is another factor that would affect female

labor force participation and a more intensive use of income-earning assets.

The connection between schooling and participation has several chan-

nels. If schooling of women increases their awareness and use of contracep-

tive methods or increases their bargaining power relative to men’s (should

men prefer more children), then more educated women will have fewer

undesired births.

24

If women enjoy better economic opportunities because

of educational attainment, the opportunity cost of their time invested in

child care increases with their schooling level. Consequently, they tend to

have fewer children if the increased opportunity cost is large enough to

offset the potential positive income effect.

25

Similarly, if the reward paid in the labor market for a fixed amount of

schooling increases, the opportunity cost of the time invested in raising

children increases, and the desired number of children tends to decline

(with the net effect depending on the income versus the price effects once

again). Conventional wisdom and much of the past empirical literature

suggest that women’s schooling is the dominant factor associated with

fertility declines, though in most studies exactly what causal role women’s

schooling is playing is not identified.

In fact, Table 14.9 shows that participation rates in Latin America increase

considerably with education.

26

For instance, in Honduras, women with no

schooling have participation rates of about 32 percent, whereas those with

higher education have a participation rate of 72 percent. The average ratio

between the participation rates of women in the lowest education category

to those in the highest category is approximately one to three.

According to Duryea and Sz

´

ekely, around 30 percentage points of the

increase in participation rates are associated with the change in the age

composition of the population. Specifically, the relative size of the thirty to

thirty-nine age group increased by 15 percent during the decade and, because

this is the group that registers the highest participation rates, total female

24

Mark Rosenzweig and Paul Schultz, “The Supply and Demand for Births: Fertility and Its Life

Cycle Consequence,” American Economic Review 75, 5 (1985): 992–1015;Mark Rosenzweig and Paul

Schultz, “Fertility and Investments in Human Capital: Estimates of the Consequences of Imperfect

Fertility Control in Malaysia,” Journal of Econometrics 36 (1987): 163–84.

25

Michael Kremer and Daniel Chen, “Income Distribution Dynamics with Endogenous Fertility,”

American Economic Review (May 1999).

26

The only exception is Peru in 1985.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Poverty and Inequality 623

participation increased. The relative size of the forty to forty-nine group –

which registers lower participation rates – also expanded and this tended to

reduce participation. However, because this expansion was smaller (around

8%), it was offset by the change in the thirty to thirty-nine age group. With

respect to the 1990s, female participation continued to expand, although

at a slower pace. In the 1980s, the average annual increase was 3.4 percent;

in the 1990s, it fell to 2.4 percent.

What are the forces causing the changes in the age structure that affect

the use of human capital through female labor force participation? Shifts in

age structure are mainly triggered by changes in fertility and mortality that

have taken place some years before becoming manifest. With constant age-

specific fertility and mortality rates, a population grows at a steady rate and

the age structure remains stable. However, if fertility and mortality decline

at different rates, as is the case during the stereotypical demographic transi-

tion from a high-fertility/high-mortality steady state to a low-fertility/low-

mortality steady state, population growth and dependency ratios vary. Dif-

ferences in age structures and dependency ratios across countries today are

attributable mainly to differences in fertility rates and to the varying paces

at which they have declined over time.

Decreased fertility is typically associated with increased female schooling.

Surveys of the literature on fertility repeatedly suggest that the strongest

empirical association between fertility declines and observed variables in

micro and aggregate studies is the inverse one between women’s schooling

and fertility. In a summary of the empirical literature, Birdsall finds that

female education of over four years bears one of the strongest and most

consistent negative relationships to fertility, and that empirical work has

strongly confirmed the hypothesis that parents’ education – especially a

mother’s education above the primary level – is associated with lower fertil-

ity.

27

Schultz also implies that increasing educational attainment of women

is generally associated with reduced fertility.

28

Another factor affecting fertility is health. The more precarious are health

conditions, the lower the probability of the survival of each child and,

therefore, the larger the number of pregnancies required to be able to meet

the target number of adult children. If health conditions improve, thereby

reducing infant mortality rates and increasing life expectancies, people will

27

Nancy Birdsall et al., “Why Low Inequality Spurs Growth: Saving and Investment by the Poor,” in

Andr

´

es Solimano, ed., Social Inequalities: Values, Growth and the State (Ann Arbor, MI, 1998).

28

Schultz, “Inequality in the Distribution of Personal Income in the World: How It Is Changing and

Why” (Mimeograph, Yale University, 1997).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Table 14.9.

Participation rates for men and women ages

30–45 by level of completed schooling (percent)

Women

Men

ABCDAB

CD

Country and year No education Primary Secondary

Higher No education Primary Secondary Higher

Brazil 81

0.34 0.37 0.53 0.82 0.95 0.

97 0.97 0.98

Brazil 95

0.50

.57 0.67 0.87 0.92 0.95 0.97

0.987

Chile 87

0.25 0.30

.39 0.70

.81 0.94 0.96 0.98

Chile 94

0.34 0.36 0.46 0.74 0.80

.95 0.98 0.98

Colombia

95

0.42 0.46 0.61 0.87 0.92 0.98

0.98 0.98

Costa Rica

81

0.87 0.91 0.93 0.93 0.91 0.96

0.98 0.93

Costa Rica

95 0.34 0.35 0.48 0.70

.87 0.97 0.98 0.97

Ecuador

95

0.68 0.61 0.62 0.81 0.88 0.96

0.98 0.98

El Salvador

95 0.41 0.57 0.70

.90

.89 0.93 0.94 0.94

Honduras

89

0.26 0.40

.61 0.76 0.96 0.98 0.95 0.97

Honduras

96

0.32 0.49 0.60

.72 0.95 0.98 0.98 0.97

Mexico 84

0.37 0.39 0.47 0.72 0.74 0.97

0.98 0.98

Mexico 94

0.37 0.39 0.47 0.72 0.74 0

.97 0.98 0.98

Nicaragua

93

0.33 0.49 0.66 0.72 0.90

.89 0.89 0.95

624

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Panama

95

0.20

.34 0.55 0.83 0.84 0.96 0.96

0.97

Paraguay

95

0.72 0.72 0.73 0.86 0.79 0

.98 0.99 0.99

Peru 85/60

.82 0.78 0.66 0.78 0.92 0.

98 0.96 0.97

Peru 96

0.77 0.71 0.64 0.72 0.89 0

.98 0.94 0.97

Venezuela

81

0.23 0.33 0.52 0.76 0.95 0.98

0.98 0.97

Venezuela

95

0.31 0.41 0.60

.83 0.90

.97 0.97 0.96

Argentina

81

∗

0.63 0.34 0.42 0.71 0.98

0.98 0.98 0.97

Argentina

96

0.64 0.48 0.56 0.80

.75 0.96 0.98 0.99

Bolivia

86

∗

0.45 0.43 0.48 0.61 0.87

0.96 0.97 0.87

Bolivia

95

0.68 0.68 0.63 0.80

.95 0.98 0.97 0.96

Uruguay

81

∗

0.47 0.47 0.52 0.80

.63 0.97 0.98 0.99

Uruguay

95

0.34 0.59 0.73 0.91 0.40

.97 0.99 0.99

∗

The surveys for Argentina include only Gran Buenos Aires. The surveys

for Bolivia include only urban. The surveys for Uruguay

include only urban.

Source: Suzanne Duryea and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, “Schooling Investments and Agrregate Conditions: A Household-S

urvey Approach

for Latin America and the Caribbean” (Working Paper no.

407,I

nter-American Development Bank,

1999).

625

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

626 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

perceive these changes. They will then respond rationally to the knowledge

that they will be able to achieve their expected desired family size with

fewer births because of increased probabilities of survival to adulthood.

Furthermore, with longer expected life spans, the returns to human resource

investments are greater. This shifts the incentives toward investing more

in each child – and having fewer of them – and away from having a high

number of children.

According to estimates of Behrman, Duryea, and Sz

´

ekely for Latin

America as well as other regions, the two key variables that affect fertil-

ity trends are the differences in female schooling and in health. Female

schooling differentials are consistent with about three-quarters of the dif-

ference in fertility, with secondary school being most important, followed

by tertiary. Better health in the developed than in the developing world

as represented by the life-expectancy-at-age-one variable is consistent with

about one quarter of the difference.

In the case of Latin America, the association with female schooling is

larger and with health smaller than for all developing countries combined.

For female schooling in Latin America, differences in secondary schooling

have particularly strong associations and those for tertiary schooling also

are relatively large. Because Latin America has a higher proportion of its

female population over twenty-five years of age with completed schooling

only at the primary level than do the developed countries, differences in

this schooling level are associated negatively with the fertility difference.

In sum, the main change taking place in Latin America with regard to the

use of human capital in the region is the increase in female participation

rates. Whereas male participation is fairly stable across age groups and

across the income distribution, female participation is highly influenced

directly by education, fertility, and demographic changes. Among these

three factors, education plays a major role because it affects participation

indirectly through its effects on fertility and on future age structures, in

addition to its direct impact.

This is an important conclusion because it reveals that education may

have affected income inequality and poverty in Latin America during the

past century through various channels. The most direct channel has been

that education is an asset in itself and, therefore, it determines the potential

that an individual has for generating income. Indirectly, schooling affects

income by influencing the possibilities of using the income-earning assets

acquired. The analysis in this section reveals that the possibilities of putting

human capital to work are highly influenced by schooling. The greater the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Poverty and Inequality 627

education level, the greater the chances of using education in the labor

market to generate income.

investment: the use of capital assets

Physical capital in Latin America has been as unevenly distributed and

used as human capital. The behavior of this asset in terms of investment

in productive activity (use of physical capital) in the region has been one

of constant instability. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) stagnation char-

acterized the region for more than two decades, until the 1980s, when the

debt crisis hit. Instead of following a recovery trend at the beginning of

the 1990s, investment rates went into a steep slide, leaving the region far

behind other countries that had had similar levels.

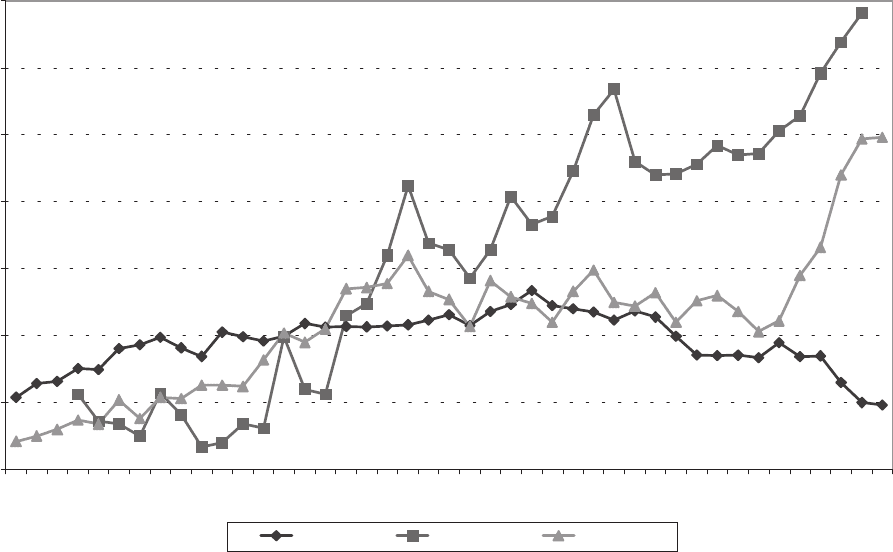

As shown in Figure 14.11, Latin America entered the 1950s with similar

ratios of real investment to GDP as those of Southeast Asian countries

such as South Korea and Thailand. Economic upheavals then induced

Latin America to raise its levels of investment from 10 percent to 15 percent

of GDP in only a decade, while South Korea and Thailand were only

investing 8 percent and 11 percent, respectively. Nonetheless, within a brief

period of time, this situation had changed dramatically.

The 1960swere a stagnant decade for Latin America, during which eco-

nomic inactivity with respect to FDI was a feature distinguishing the region.

Investment did not fall, with some years showing no growth or very low

growth rates and others showing modest increases at best. South Korea

and Thailand, on the other hand, took the opposite course. South Korea

showed an exponential investment rise over the course of the 1960s. By

the 1970s, while Latin America was experiencing an investment rate of

16 percent, South Korea was leaps and bounds ahead, at 27 percent.

Thailand followed a somewhat similar trend, but its investment growth

rates were not as impressive as those of South Korea. Thailand’s shares con-

tinued to grow steadily, however, and by the 1970s, its rate was 21 percent –

low in comparison to Korea’s 27 percent but higher than Latin America’s

16 percent.

Latin America and Thailand performed similarly during the 1970s, going

through ups and downs, while Korea continued to increase its invest-

ment rate. By the 1980s, Korea’s share was almost 35 percent whereas Latin

America and Thailand were still stuck in the 20 percent range. The 1990s

brought economic crises that inflicted critical setbacks on all three coun-

tries. Although investment shares diminished across the board, recovery

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

5.00

10.00

15.00

20.00

25.00

30.00

35.00

40.00

1950

1952

1954

1956

1958

1960

1962

1964

1966

1968

1970

1972

1974

1976

1978

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

LAC

Korea

Thailand

Figure 14.11.R

eal investment share of GDP (%) (1995

international prices).

Source:

Penn World Table

1994.

628

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Poverty and Inequality 629

came sooner for the Asian countries. Latin America’s rates continued

their downward slide, widening the ever-expanding gap between the Latin

American region and the two Southeast Asian countries.

As for the use of land, the percentage of arable land used in agriculture

in Latin America is not particularly high (Figure 14.12). In fact, it is low

compared to other regions. It accounted for only 4 percent of the total

land area at the beginning of the sixties, when the average for the world

was more than twice that number. The share remained relatively constant

(reaching 6.5%) at the end of the twentieth century, when the percentage

for East Asia reached 12 percent. Consequently, the rate of use of this

income-earning asset has been rather modest. As shown in the previous

section, land is highly concentrated in the few countries for which data are

available. Given its low rate of use and high returns, this would be expected.

ASSETS, PRICES, AND RETURNS

Prices reflect the rate of return that assets earn when they are put to work

in the market. For the purposes of this section, the focus is on the returns

to education as reflected in income and the returns to capital as reflected in

interest rates. Unlike other variables such as levels of education or fertility,

returns to assets are not nearly as heavily influenced by individual decisions.

Rather, they are determined to a large extent by supply and demand, as

well as by institutional factors, on which each individual exerts a negligible

degree of influence. Prices are therefore mostly set by the economic system,

and their interaction with the individual begins when he or she embarks

on the process of seeking income or accumulating a certain type of capital.

returns to education: the price received for putting

human capital to work

If the relative demand for different skills had remained the same over time,

even meager improvements in school attainment by the Latin American

population should have been associated with a relative decline in the earn-

ings of the more educated. However, the evidence shows that this was

not so.

Table 14.10 gives the coefficient estimates for the trend followed by the

(log) wage gap between individuals with higher, secondary, and primary

education for fifteen Latin American countries for years between 1977 and

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

1961

1963

1965

1967

1969

1971

1973

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

LAC

Sub-Saharan Africa

East Asia & Pacific

World

Figure 14.12. Land use in Latin America, arable land (% of land area).

Source:

World Bank, Wo

rldDevelopment Indicators

2002

(Washington, DC,

2002).

630

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Poverty and Inequality 631

Table 14.10. Country trends for wage gaps and overall policy

Country

Higher to secondary

wage gap

Higher to primary

wage gap

Paraguay 0.1008 0.1482

El Salvador 0.0736 0.0942

Colombia 0.0181 0.0661

Mexico 0.0152 0.0287

Ecuador 0.0177 0.0283

Chile 0.0146 0.0241

Nicaragua 0.0561 0.0209

Costa Rica 0.0198 0.0198

Peru 0.0061 0.017

Uruguay 0.0074 0.0129

Panama 0.0103 0.0082

Bolivia 0.0097 0.0065

Argentina 0.0093 0.0012

Venezuela 0.0064 −0.0009

Honduras 0.0102 −0.0017

Average all LAC 0.0155 0.01817

Source: Jere Behrman, Nancy Birdsall, and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, Poverty and

Income Inequality in Developing Countries: A Policy Dialogue on the Effects

of Globalization (Paris, 1999).

1998.Apositive trend means that the gap has been expanding. Interest-

ingly, the higher-education-to-secondary-school wage gap has augmented

in all fifteen countries during the past two decades. The countries where the

higher–primary wage gap (second column) increased the most are Paraguay,

El Salvador, and Colombia. The only three countries where the gap nar-

rowedare Argentina, Venezuela, and Honduras. Paraguay and El Salvador

are also the countries where the higher–secondary wage gap increased

the most, while Colombia registered a more moderate increase than in the

higher–primary gap. Peru and Argentina are the two countries where the

increase in the higher–secondary gap was smallest, but there is no country

where the gap narrowed. The correlation between the coefficients in Table

14.10 is 0.86, which indicates a high (although not perfect) correspondence

between changes in the higher–primary and higher–secondary wage gaps.

On average, wage differentials in the region have increased substantially

during the 1990s. Figure 14.13 shows that the average differential among

the same fifteen counties expanded considerably during the first half of

the decade and remained fairly stable thereafter. The higher-to-secondary