Bulmer-Thomas V., Coatsworth J., Cortes-Conde R. The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America: Volume 2, The Long Twentieth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

602 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

Latin American countries.

13

Arecent paper by Lundberg and Squire argues

that changes in GDP and in income inequality are jointly determined and

should therefore be examined in a system of simultaneous equations in

which the direct relationship between these two variables is of secondary

interest.

14

Therefore, after considerable controversy and empirical testing, the jury

is still out on the relationship between development levels and inequality as

postulated by Kuznets. Many scholars have devoted their efforts to trying to

either prove or disqualify this hypothesis, opening the door for many ques-

tions. Given the scarcity of evidence, the only verifiable – and alarming –

conclusion is that Latin America seems to have remained on the top part

of the curve for many years already, without showing any decline in the

inequality trend, but rather a constant and upward-rising trend toward

more poverty and inequality.

poverty, inequality, and growth

As for poverty, the straightforward explanation is that its evolution depends

mainly on economic growth.

15

To engage in this analysis, first one must

identify who counts as belonging to the group of “poor” and then deter-

mine how to measure the incomes of that group to track changes in their

conditions over time.

One approach widely followed for defining the poor is a relative defini-

tion, such as all people in the lowest quintile or decile. The central question

this approach seeks to address is the nature of the relationship between eco-

nomic growth and growth in the income standard of the poor, and whether

the growth elasticity of this income standard exceeds, equals, or falls below

unity. The earlier papers in this strand of literature – including Adelman

and Morris; Ahluwalia; and Ahluwalia, Carter, and Chenery – were

13

Robert Barro, “Inequality and Growth in a Panel of Countries” (Mimeograph, Harvard University,

1999); Alain De Janvry and Elizabeth Sadoulet, “Growth, Poverty and Inequality in Latin America:

A Causal Analysis, 1970–1994,” Review of Income and Wealth 46, 3 (2000): 267–87;Samuel Morley,

La distribuci

´

on del ingreso en Am

´

erica Latina y el Caribe (Mexico City, 2000).

14

Mattias Lundberg and Lyn Squire, “The Simultaneous Evolution of Growth and Inequality,”

(Mimeograph, Washington, DC, 2000).

15

Many other factors have been considered to be of influence regarding poverty and inequality in

Latin America. This includes macroeconomic fluctuations such as high inflation periods, as well as

structural and demographical trends like migration. Although these trends have certainly influenced

the evolution of poverty in the region, the main objective of the current study is to first observe the

relationship between economic growth and poverty alleviation and, second, to study the development

of physical and human assets and its incidence in the well-being of Latin America.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

Poverty and Inequality 603

primarily interested in the growth–inequality relationship (with one

inequality measure being the income share of the poor group), but they also

asked whether the poorest 20 percent of the population shared the benefits

of growth proportionally.

16

These authors conclude that the income share

of the poor tends to decline in the early stages of development but increases

in the long run.

This approach has received renewed attention recently. Romer and

Gugerty, Gallup, and Dollar and Kraay state that the growth elasticity

of the incomes of individuals in the bottom quintile is essentially equal

to one.

17

Timmer obtains a more modest elasticity of around 0.9.

18

Even

though these studies use the same data and similar econometric techniques,

they disagree on the issue of whether growth leads to a proportional increase

in the income of the poor – in other words, if the gains for the poor are

smaller than those of other groups.

The second approach to poverty and inequality measurement tracks

income poverty levels using an absolute poverty line and a standard poverty

measure. Ravallion, Ravallion and Chen, and Bruno employ absolute

poverty lines of one and two dollars a day to identify the poor and then

aggregate, using the most common measures of poverty, the head count

ratio and the per capita poverty gap.

19

These studies find that the growth

elasticity of the head count ratio is normally below a minus-two level. In

other words, when average income increases by 1 percent, the proportion

of poor declines by more than 2 percent. Hence, the results not only show

that the relation between growth and poverty reduction does not function

on a merely one-to-one basis, but they further imply that growth is the

main vehicle for poverty reduction.

Other authors such as Morley, De Janvry and Sadoulet, and Smolensky

also use poverty lines that combine an absolute and a relative compo-

nent, but their elasticities are highly sensitive to the location of the poverty

16

Irma Adelman and Albert Morris, Economic Growth and Social Equity in Developing Countries (Stan-

ford, CA, 1973); Montek Ahluwalia, “Inequality, Poverty and Development,” Journal of Development

Economics 2 (1976): 307–42;Montek Ahluwalia, Nicholas Carter, and Hollis Chenery, “Growth and

PovertyinDeveloping Countries,” Journal of Development Economics 6 (1979): 299–341.

17

Michael Roemer and Mary Kay Gugerty, “Does Economic Growth Reduce Poverty?” (Discussion

Paper no. 4,Harvard Institute for International Development, Harvard University, 1997); John Luke

Gallup et al., “Economic Growth and the Income of the Poor” (Harvard Institute for International

Development, Discussion Paper no. 36,Harvard University, 1999); David Dollar and Aart Kraay

“Growth Is Good for the Poor” (Mimeograph, Washington, DC).

18

Peter Timmer, HowWell Do the Poor Connect to the Growth Process (Cambridge, MA, 1997).

19

Martin Ravallion, “Growth and Poverty: Making Sense of the Current Debate” (Mimeograph, World

Bank, Washington, DC, 2000).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

604 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

line.

20

The growth elasticity of poverty ranges from −2.59 to −0.69,

depending on whether the threshold is established at 50 percent or 100

percent of the average income at the initial period of observation.

Foster and Sz

´

ekely propose an alternative methodology to track low

incomes, based on Atkinson’s family of “equally distributed equivalent

income” functions denominated “general means.”

21

Based on this method-

ology, they estimate the growth elasticity of the general means and use 144

household surveys from twenty countries that cover the last twenty-five

years of the twentieth century. Among other results, they found that poor

individual incomes do not grow on a one-to-one basis with the increases

in mean income. Therefore, their conclusions differ from others that use

per capita income of individuals in the first quintile as an income standard

of the poor and argue that the growth elasticity of this income standard is

unity. Foster and Sz

´

ekely estimate the relationship for a set of Latin Amer-

ican countries and conclude that the elasticity of the income of the poor to

economic growth is also lower than one.

In sum, even though the relationship between growth and poverty is

evidently close, the available evidence indicates that growth itself cannot

fully explain changes in poverty in the region.

some final considerations

From the previous discussion, it is possible to assert that even in cases where

the inequality–development relationship does seem to follow the inverted

U pattern suggested by the main development theories, extreme poverty has

not declined consistently as a natural outcome of the development process,

contrary to expectations. Moreover, the mechanisms through which poverty

was supposed to change were actually only observed during a relatively short

subperiod (1977–84).

In some cases (e.g., Mexico) it can be found that, contrary to what the

theory predicts, the main cause of the change in the standard of living of

the extremely poor after the turning point in the inequality-development

relationship was that the rural–urban gap continued to expand, generating

20

Alain De Janvry and Elizabeth Sadoulet, “Growth, Poverty and Inequality in Latin America: A Causal

Analysis, 1970–1994”; Eugene Smolensky et al., “Growth Inequality and Poverty: A Cautionary

Note,” Review of Income and Wealth Series 40, 2 (1994): 217–22.

21

James E. Foster and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, “Is Economic Growth Good for the Poor? Tracking Low Incomes

Using General Means” (Working Paper no. 453,Inter-American Development Bank, 2001).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

Poverty and Inequality 605

significant poverty-increasing effects. The distribution of income within

the subgroups, implicitly assumed constant, also changed considerably in

most of the years.

Overall, this implies that, at least in some cases, the results are not in

line with the Kuznets hypothesis, which would have predicted a consistent

improvement in the standard of living of the poor after the turning point.

Even in the context of positive economic growth and declining inequal-

ities, a deterioration in the standard of living of the poorest is observed.

Uncertainty about the accuracy of the Kuznets hypothesis could be well

extrapolated to an entire region such as Latin America, which has borne the

twin burdens of poverty and inequality for a long period of time, despite

extended periods of economic growth.

INCOME-EARNING ASSETS IN

LATIN AMERICA

assets, prices, and returns: an asset-based approach

Traditional explanations arguing that economic growth can explain the

evolution of poverty and inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean

are clearly insufficient for understanding the persistently high levels in the

region. In the spirit of Engermann and Sokoloff, one could argue that the

main factor driving the persistently disparate income levels is the skewed

distribution of factor endowments, or income-earning assets, among indi-

viduals.

One way to pursue this analysis is to acknowledge that the income of

each individual in a society is a function of the combination of four essential

elements: first, the stock of income-earning assets owned by each individual

(classified as either human or physical capital); second, the extent to which

these assets are employed in producing income; third, the market value

of income-earning assets; and fourth, the income received independently

of income-earning assets, which may include transfers, gifts, and bequests,

among others. Consequently, family per capita income can be expressed in

the following equation:

y

i

=

j

i=

i

a=

A

a.i

R

a.i

P

a

+

k

i=

T

i

n

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

606 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

where y represents the household per capita income of the individual i ; A

is a variable representing the stock of asset type a,owned by an individual

i ; R is a variable representing the rate at which asset type a is used by

individual i ; and P is the market value per unit of asset type a. The variable

j represents the number of income-earners in the household to which the

individual i belongs, l is the number of different types of assets, and k is the

number of individuals in the household obtaining income from transfers

and bequests, whereas n is the size of the household to which i belongs.

For simplicity, here we classify income-earning assets into human and

physical capital. Human capital assets are the set of skills endowed by

individuals – such as knowledge, capability, or expertise – and the health

that enables them to produce any good or service. The most widely used

proxy for quantifying knowledge is years of formal education. Other types

of skills acquired through experience or training programs are not always

available and are more difficult to measure. Information on labor market

experience is also seldom available. Therefore, the definition of human

capital is restricted to years of schooling and health.

On the other hand, physical capital refers to the monetary value of any

form of financial asset, be it money holdings, property, rents, capital stock

used for production, or any other form of physical capital used to produce

a good or service. These stocks can be used in several ways; they can either

be invested for production or accumulated to function as savings.

In terms of opportunity to use the assets productively, the two clear areas

are employment and investment opportunities. Employment opportuni-

ties refer to the conditions, costs, and incentives in the labor market that

influence the demand for different kinds of labor and the demand for skills.

Investment opportunity comes from the existence of an efficient financial

market that gives access to credit. Credit can be used to create economic

activity and to take advantage of the economic environment to generate

income.

Ownership, or other avenues of access to any of these income-earning

assets, implies that an individual has the potential capacity to generate

income at some point in time, but the income that is actually generated

depends on the use of the asset. For instance, in the case of human capital,

the years of schooling of an individual will only be translated into income

when that person becomes gainfully employed. Regarding physical capital,

it will only produce income when the dividend or return generated by the

asset is made liquid.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

Poverty and Inequality 607

Tu rning to the third income component, prices and returns for each

income-earning asset, the behavior of prices is somewhat unique because

it is determined by supply and demand, as well as by institutional fac-

tors. Prices and returns are therefore set by the economic system, and the

individual responds to them in the process of deciding whether to seek

income and accumulate a certain type of capital. Unlike the other two

income components, the individual exercises very little control over prices

and returns.

Finally, the fourth element in the income-generating process described

earlier is transfers, bequests, and gifts that a household receives and that are

not directly related to income, prices, or returns.

There is certainly a link between assets, their use, and poverty. As we

show subsequently – for instance, in the case of human capital – the poor

have smaller stocks. They receive the lowest rewards not only for having a

small stock, but also because the returns are nonlinear and increase with the

size of the stock. Finally, because of the low returns, the poor and, specifi-

cally, women ultimately end up using these assets at a much lower rate.

In an attempt to improve our understanding about why poverty and

inequality in Latin America have historically been so high, we explore long-

term trends in the underlying factors determining incomes: assets, use, and

returns. This section examines the process of human and physical capital

accumulation in Latin America in order to assess how the distribution of

these assets evolved in the region during the past century.

human capital accumulation through

schooling attainment

Because Latin America is characterized by increasingly high wage inequal-

ity, it is essential to know how human capital is distributed as well as how its

distribution changes over time. This section establishes some of the more

general trends followed by Latin America throughout the century, exam-

ining changes in both the flows and stocks of schooling. South Korea and

Taiwan are interesting cases for comparison because they are regarded as

having achieved outstanding schooling progress during the twentieth cen-

tury. Comparisons of Taiwan and the Latin American region are presented

subsequently.

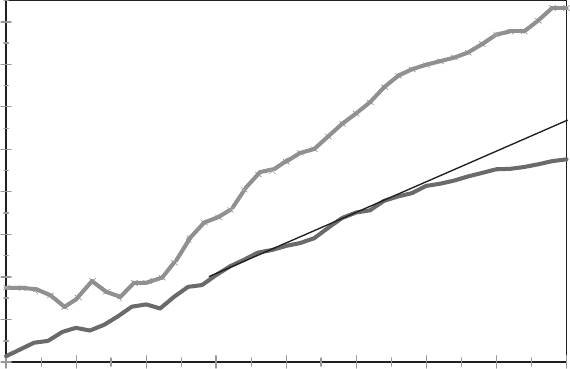

Figure 14.5, taken from Behrman, Duryea, and Sz

´

ekely, plots schooling

attainment for Taiwan and the average Latin American country for all

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

608 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Year Dummy Coefficient, FE regression

1930 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970

Year of Birth

Pattern for

Taiwan

LAC pattern

LAC trend

1940-1960

Figure 14.5.Pattern of schooling progress in Taiwan and Latin America.

Source: Jere Behrman, Suzanne Duryea, and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, “Schooling Investments

and Aggregate Conditions: A Household-Survey Approach for Latin America and the

Caribbean” (Working Paper no. 407,Inter-American Development Bank, Washington,

DC, 1999).

cohorts (or groups of individuals) born between 1930 and 1970.

22

The

figure shows that, on average, Latin America and Taiwan had very similar

levels of schooling among cohorts born before 1940, but from that year on,

progress in Taiwan shot upward. Thirty years later, cohorts in Taiwan were

registering attainment levels almost 50 percent greater than the average

Latin American country. The figure also shows the slowdown in Latin

America for the 1960–70 birth cohorts. Cohorts born in those years were

making schooling decisions that coincided with the early years of the debt

crisis in the region. The figure also plots a trend line in Latin America from

22

Household surveys for years around 1995 are used to produce this figure. Therefore, cohorts born in

1930 were about 65 years of age at the time of the survey, whereas those born in 1970 were around the

age of 25. The figure does not include information on more recent cohorts (born after 1970) because

a considerable share of individuals born after 1970 have not yet completed their schooling; hence,

it is not clear what their attainments will be. The Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) pattern

was obtained by pooling all the information on the average years of schooling by year of birth, for

18 countries, and estimating a country fixed-effects regression using the average schooling of each

cohort as the dependent variable and dummy variables for each year as the right-side variables. The

figure plots the coefficients for the year dummies.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

Poverty and Inequality 609

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

8.0

9.0

10.0

11.0

12.0

13.0

1930 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970

Year of Birth

Taiwan

Mexico

Nicaragua

Brazil

Chile

Korea

Average Year of Completed Schooling

Figure 14.6.Mean years of schooling by cohort.

Source: Jere Behrman, Suzanne Duryea, and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, “Schooling Investments

and Aggregate Conditions: A Household-Survey Approach for Latin America and the

Caribbean.”

1940 to 1960.Had the same trend continued for cohorts born after 1960,

the average years of schooling for the last cohort would have been close to

10 years, rather than around 8.5.

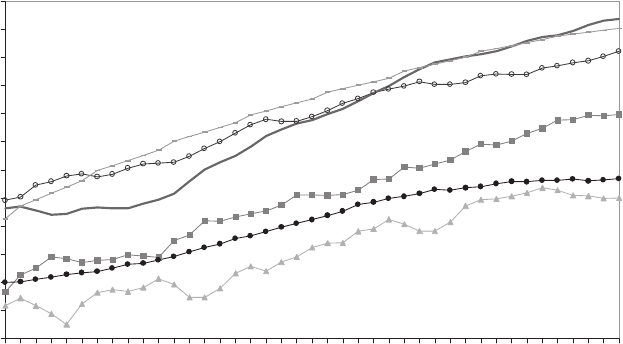

Figure 14.6 plots information on cohorts born between 1930 and 1970 for

a selected group of countries: Chile (one of the countries in Latin America

with the highest current schooling levels and second only to Argentina

for the 1970 birth cohort), Mexico (the country in Latin America with

the greatest growth in mean years of schooling between the 1930 and 1970

birth cohorts), Brazil and Nicaragua (two of the countries in Latin America

with the poorest schooling performances), and Korea and Taiwan. All of

these countries display significant improvements in mean schooling for

individuals born between 1940 and 1960, though more for Taiwan than for

the others. Yet in Taiwan and South Korea, schooling increased at faster

rates for persons born after 1960 than did most of Latin America, with the

exceptions of Mexico and the Dominican Republic. For example, Chile

and Taiwan had similar mean schooling for people born between 1950

and 1955, but those born in 1970 in Taiwan have, on average, one more

grade of schooling than their Chilean counterparts. On the other hand,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

610 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

the large differences between Mexico and the Dominican Republic versus

South Korea and Taiwan that can be observed today are not attributable

to greater progress in these two East Asian countries for the most recent

cohorts but rather to their much higher levels at the start of the period

covered.

Not all countries in the Latin American region registered the same spread

of education progress. For example, Honduras reported no increases in

educational attainment for more than a decade for the cohorts born between

1925 and 1940, and it was not until the early 1950s that significant increases

were reported.

In Table 14.4, information on the average years of schooling is presented

for various cohorts. Seventeen countries in Latin America are listed in

increasing order of mean schooling attainment for those born in 1930.

Similar data for South Korea, Taiwan, and the United States are given at

the bottom of the table. This table clearly portrays the upward trend for new

generations of Latin Americans. Although advancements are notable for all

countries, there is considerable disparity among nations. Brazil entered

the century with one of the lowest levels, much like those of Honduras.

Chile and Panama, on the other hand, had educational attainments almost

three times higher than those of Brazil at the turn of the last century.

Notwithstanding the progress reported, the table shows that many countries

have suffered important setbacks regarding education.

On average, there was an increase of 4.6 years of schooling in the seven-

teen Latin American countries from the cohort born in 1930 to the one born

in 1970. The largest increases were in Mexico, the Dominican Republic,

Chile, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Venezuela, all of which boasted a gain of more

than five years during the period. The smallest changes were in Jamaica,

Paraguay, Brazil, and Nicaragua, all with less than four years. In contrast,

South Korea and Taiwan made impressive strides in schooling attainment,

boosting average years of education by 6.8 and 6.5 years, respectively, dur-

ing the same period. Recent generations in these nations are approaching

the schooling attainment levels of the United States.

Educational attainment levels in Latin America improved by only one

year per decade in the region. Given this sluggish growth, the supply of

the highest skills has also been quite slow to increase and has not been

able to keep pace with the growing demand. This predicament has been

a common one across the region and, as a result, the wages of highly

educated individuals relative to unskilled employees have risen (see the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14 CB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 10:49

Poverty and Inequality 611

Table 14.4. Average years of schooling by birth cohort

Year of birth Change

Country 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1930–1950 1950–1970 1930–1970

Honduras 1.43.24.65.66.13.21.44.7

Nicaragua 23.24.35.85.82.21.63.8

El Salvador 2.13.24.15.77 2 2.94.9

Brazil 2.83.65.26.26.72.41.53.9

Mexico 2.94.26.78.29.33.82.66.4

Dominican

Republic

3.24.27 8.69.13.92.15.9

Venezuela 3.25.16.97.98.33.71.45.1

Bolivia 3.34.56.37 8.62.92.35.2

Ecuador 3.94.56.58.59.52.63 5.6

Colombia 3.94.46.27.78.42.32.24.4

Costa Rica 4.35.77.18.88.42.81.34.1

Chile 5.27.18.910.111.13.72.15.8

Panama 5.86.98.810.310.13.11.34.4

Peru 66.37.49.410 1.42.64

Uruguay

∗

6.37.48.810 10.72.51.94.4

Jamaica 6.97.98.39.610.61.42.33.7

Argentina

∗

7.58.310 11 11.32.51.33.8

Average

LAC

4.15.36.98.28.82.71.94.6

Korea 5.37.79.511 12 4.32.56.8

Taiwan 5.85.88.911 12.33.23.36.5

USA 12.312.913.613.313.41.3 −0.21.1

∗

The survey for Argentina includes only Gran Buenos Aires; the survey from Uruguay covers only

urban areas.

Sources: Suzanne Duryea and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, “The Determinants of Schooling in Latin America:

AMicro-Macro Approach” (Working Paper, Inter-American Development Bank, 1999). Data

from Korea were taken from UNESCO Statistical Yearbook,(NewYork,1997).

fourth section), thereby contributing to the ever-widening income gap

between highly and poorly educated individuals.

Schooling progress in Latin America was considerably greater for the

generations born between 1930 and 1950 –again of 2.7 years – than for

those born between 1950 and 1970 –again of 1.9. The deceleration appears

to be steeper in Honduras, Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and Panama,

where progress for cohorts born between 1930 and 1950 was more than 1.5