Bulmer-Thomas V., Coatsworth J., Cortes-Conde R. The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America: Volume 2, The Long Twentieth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

152 Victor Bulmer-Thomas

companies, to switch out of domestic currency debt into foreign bonds.

The result was an unhealthy expansion of external indebtedness in many

countries, particularly Argentina and Brazil, which were vulnerable to a

widening of the risk premium and any unwillingness of the bond mar-

kets to refinance. When Argentine difficulties finally surfaced in 2001, the

country was found to account for 25 percent of all emerging market fixed

interest debt.

If Latin America’s attempts to tap into the international bond market

were too successful, the opposite was true of its efforts to attract equity

capital. All attempts to broaden the appeal of the local stock markets failed.

Only a small number of stocks were listed, most domestic companies pre-

ferring to remain 100 percent controlled by their family shareholders. Most

of the listed stocks were not actively traded, so liquidity was a serious prob-

lem. The larger firms sought a listing as American Depositary Receipts

(ADRs)

34

on the New York exchange and mergers and acquisitions by for-

eign companies led some of the most important companies to delist. By

2000, only two markets – S

˜

ao Paulo and Mexico City – had any appeal

for foreign investors, and stocks in these markets accounted for 80 to 90

percent of the typical Latin American fund.

Latin America’s liberalization of the capital account was therefore less

satisfactory than its liberalization of the current account. Many of the

smaller countries remained unattractive to foreign capital regardless of what

they did, and DFI flowed primarily to mineral extraction and former SOEs.

Assembly plants set up by foreign companies flourished in parts of the

Caribbean Basin, but this was a reflection of temporary tax breaks in the

United States more than anything else.

35

The larger countries, on the other

hand, became too dependent on the foreign currency bond market. Mexico

was the first to suffer (in 1994) but was rescued by its international creditors

and was able to use currency depreciation to build up a massive export

capacity. Argentina and Brazil were not so fortunate.

Latin America’s efforts to adjust to globalization through liberalization of

the current and capital accounts were matched by reforms to the domestic

economy. Indeed, to a large extent, the external adjustment required a

domestic response. This was particularly true of monetary and fiscal policy

34

These ADRs were deemed to be much more liquid and were therefore popular with foreign investors.

For U.S. investors, they had the additional advantage of avoiding exchange rate risk.

35

The most important of these tax breaks was the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI), first introduced in

1984. This led to a boom in assembly plants in many countries, but a number of factories transferred

production to Mexico after the adoption of NAFTA.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

Globalization and the New Economic Model in Latin America 153

where irresponsible behavior was now much more likely to be punished.

Thus, high rates of inflation could not be tolerated when tariffs were falling

(trade liberalization) and real exchange rates rising (capital inflows).

Monetary policy has been transformed in Latin America in the lasttwenty

years. Central banks have become much more autonomous (e.g., Brazil) and

some have been given complete independence (e.g., Mexico). Regulation

of the banking systems has been improved and the entry of foreign banks

has increased efficiency, even if competition is still limited. The ability of

the public sector to monetize fiscal deficits has been severely curtailed. The

outcome, as we will see in the next section, has been a big fall in inflation

in Latin America to rates that have not been seen for decades. Indeed, such

has been the improvement in the quality and credibility of monetary policy

that nominal exchange rate devaluation is no longer necessarily a guide to

the rate of inflation.

36

The most serious weakness in monetary policy has been the failure to

lower the real cost of borrowing. This is partly because of the shallowness

of the financial markets, but also because of the huge spread between bor-

rowing and lending rates. Indeed, it is not unknown for the real lending

rate to be close to zero while the real borrowing rate is above 10 percent.

Lack of competition in the financial markets is primarily to blame, and this

has not yet been overcome through liberalization of the capital account

of the balance of payments. In practice, only the largest Latin American

companies have access to the international capital market so that small

and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are restricted to borrowing in the

domestic market and are crippled by high rates.

This unsatisfactory state of affairs arises in part because financial insti-

tutions have become major creditors to the public sector and are not so

dependent on private sector business. As mentioned previously, the foreign-

currency bonds are often held by domestic agents and these are principally

the banks. Thus, the banks benefit from the country risk premium and the

banks are also the most likely to hold the domestic currency debt issued by

governments.

It might appear from the aforementioned that fiscal policy did not

improve after the debt crisis. In fact, it did, but it is necessary to distinguish

between the primary balance (net of interest payments) and the nominal

balance. The primary balance has moved into surplus in most countries,

36

This has been particularly true of Argentina and Brazil, where large devaluations in 2001/2 did not

lead to a permanent increase in inflation as had originally been feared.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

154 Victor Bulmer-Thomas

as taxes have been increased, defense spending cut, and subsidies to SOEs

eliminated. Equity considerations have been largely sacrificed in the search

for increased revenues with an emphasis on broad-based sales taxes, partic-

ularly value-added tax. And federal countries have made serious efforts to

control spending by provincial governments. However, interest payments

on the public debt – both domestic and foreign – have remained a major

drain on state finances, leading to nominal deficits that were sometimes

large even when the primary balance was in surplus.

The tightness of fiscal policy, in terms of macroeconomic stability, is more

closely approximated by the primary than the nominal balance. Thus, fiscal

policy has been restrictive in many countries at the cost of lower investment

and also at the expense of social spending. Targeting of social spending on

lower income groups, promoted by the World Bank in particular, became

more popular and enjoyed some success – notably in Chile. However,

the impact of social spending has not in general improved the secondary

distribution of income.

37

The reasons for this have been complex, but two stand out. First, edu-

cational spending on universities–alarge part of the total – has favored

the middle and upper deciles of the income distribution. Second, state

spending on pensions in Latin America goes overwhelmingly to the middle

classes rather than the poor. Although most governments have privatized –

in whole or in part – their pension systems, there is a long lag before state

liabilities cease. The reason is that older workers remain in the state system

and continue to benefit until they die.

38

Although something approaching a consensus has developed in relation

to fiscal and monetary policy in Latin America since the debt crisis, the same

cannot be said about exchange rate policy. All Latin American countries,

except dollarized Panama, devalued in the 1980s and early 1990sinaneffort

to adjust the external sector, both to create resources to service the debt

and to promote exports. However, the similarity ends there. One group,

led by Argentina, marched resolutely toward fixed currencies and de facto

dollarization. Another group, led by Chile, adopted a crawling peg with a

real exchange rate target. The third group, led by Mexico after 1994 and

joined by Brazil in 1999, opted for exchange rate flexibility.

37

On the impact of social spending on income distribution, see the chapter by Miguel Sz

´

ekely and

Andr

´

es Montes in this volume.

38

Foracase study of Chile, see C. Scott, “The Distributive Impact of the New Economic Model in

Chile,” in Victor Bulmer-Thomas, ed., The New Economic Model in Latin America and its Impact on

Income Distribution and Poverty (New York, 1996).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

Globalization and the New Economic Model in Latin America 155

The first group initially enjoyed great success. Inflation came down to

international levels and was accompanied by financial deepening. However,

the risk premium did not disappear and a spread remained between domes-

tic and foreign interest rates. Thus, the logic of this group has been to move

toward de jure dollarization with Ecuador and El Salvador joining Panama.

Argentina appeared to be moving in this direction, with nearly 70 per-

cent of bank deposits denominated in dollars by the fourth quarter of

2001.However, default on the external debt at the end of 2001 triggered

a devaluation of the currency and a difficult period of pesoification as the

authorities struggled to reverse the dollarization of the 1990s.

The second group also enjoyed initial success in achieving the target.

However, the difficulty of attracting foreign capital after the Asian financial

crisis led to a dismantling of restrictions on foreign capital inflows and a

move toward full currency flexibility. Only the smaller countries, such as

Costa Rica, were able to persevere with real exchange rate targeting. Other

countries, including Chile and Colombia, effectively joined the third group

at the end of the 1990s.

Thus, Latin America found itself divided into two camps on exchange

rate policy. In the fixed exchange rate group, dollarization appeared to be

the logical step or at least a monetary union based on a regional currency.

In the other group, formal dollarization looked increasingly unlikely,

although the dollar was often used in pricing assets. Both groups claimed

to be adjusting to globalization, so that at least with respect to exchange

rate policy, the implications of world economic integration appear to have

been ambiguous.

THE OUTCOME

It is not easy at this distance to judge Latin America’s economic performance

since the debt crisis. Two decades is a short time in economic history and

there is a sharp contrast between the adjustment of the 1980s and the

recovery of the 1990s. Nevertheless, certain patterns emerge with clarity. In

what follows, I concentrate on growth, trade, capital flows, and inflation.

The equity performance is analyzed in Chapter 14 and the impact on the

environment in Chapter 9.

The rate of growth of GDP per head in the two decades since the debt

crisis is shown in Table 4.1. Although there was a modest improvement

between the 1980s and the 1990s, the result is not impressive. It can be

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

156 Victor Bulmer-Thomas

Table 4.1. Growth of GDP per head (US$ at

1995 prices), 1981–2001

1981–90 1991–2001

Argentina −2.12.1

Bolivia −1.91.0

Brazil −0.41.1

Chile 1.44.2

Colombia 1.60.6

Costa Rica −0.71.8

Cuba 2.8 −1.6

Dominican Republic 0.23.8

Ecuador −0.9 −0.1

El Salvador −1.52.0

Guatemala −1.61.2

Haiti −2.9 −2.8

Honduras −0.80.3

Mexico −0.21.5

Nicaragua −4.10.5

Panama −0.72.4

Paraguay 0.0 −0.9

Peru −3.31.8

Uruguay −0.61.8

Venezuela −3.20.3

Latin America −0.91.2

Source: Victor Bulmer-Thomas, The Economic History of

Latin America since Independence, 2nd ed. (Cambridge,

2003), 383,Table 11.4.

argued that the long-run performance should not be judged by the 1980s

because this was a period of adjustment to the excesses of ISI and the debt

crisis. However, even if the analysis is confined to the period since 1990, the

results are still disappointing, with a low average rate of growth of GDP

per head (1.2 percent) and a high variance. Furthermore, the five years after

1997 were marked by virtual stagnation in GDP per head in Latin America,

leading to it being described as the “lost half-decade.”

Since the mid-1980s, only one country (Chile) has been able unam-

biguously to exceed its performance during the inward-looking phase

of development from 1950 to 1980, although the Dominican Republic

achieved a very credible annual growth rate in GDP per head in the 1990s

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

Globalization and the New Economic Model in Latin America 157

(see Table 4.1).

39

Argentina initially improved its long-run rate of growth

of real GDP per head, but this was undermined by a deep recession after

1998.

40

The other cases of superior growth are all rather unusual. El Sal-

vador, for example, grew rapidly in the 1990s, but this was after a long civil

war, and the rate of growth is heavily influenced by the remittances sent by

all those who had left the country for the United States.

Mexico’s performance has been an illustration of the costs and benefits of

globalization. One of the first to adjust, Mexico was also quick to liberalize

its current and capital accounts and to integrate its economy into the North

American economic space. Although performance could be damaged by

domestic mistakes, as in the excessive build-up of debt in the early 1990s,

the long-run trend toward a greater dependence on the U.S. market has

become clear.

When the U.S. economy performed well, Mexico benefited handsomely.

Growth was export-led and export expansion generated a boom in other

parts of the economy despite the weak backward linkages from the maquila

industry on the northern border. The economy became less dependent

on oil and manufactured exports became less dependent on the assembly

industry. However, Mexico went into recession as soon as the U.S. economy

slowed down. With some 30 percent of its GDP in exports and nearly 90

percent of its exports going to the United States, this was perhaps inevitable.

Mexico’s economic fortunes are now increasingly bound up with those of

the United States.

41

Argentina’s performance has been a case study in the dangers of inconsis-

tent policies. On many criteria, Argentina in the 1990s was the most neolib-

eral economy in Latin America, with widespread privatization, complete

capital account liberalization, and a large measure of trade liberalization. Yet

the exchange rate policy, under which the local currency was pegged to the

U.S. dollar under a virtual currency board regime, imposed fiscal obliga-

tions on the government that were never fully respected. The result was a

lack of fiscal discipline, leading to a massive increase in external debt. As

long as the economy grew rapidly, the debt problem could be contained. It

39

The Dominican Republic, however, suffered a major banking crisis in 2003, leading to a collapse of

the exchange rate and a fall in real GDP.

40

The collapse of Argentine GDP in 2002 (it fell by 11 percent) wiped out the long-run improvement

in GDP per head that had been achieved in the first half of the 1990s.

41

Mexico has made a big effort to diversify its trading links, signing free trade agreements with other

Latin American countries as well as with the European Union. However, the gravitational pull of the

United States has proved irresistible and the links with the United States have, if anything, grown

stronger.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

158 Victor Bulmer-Thomas

became unsustainable, however, when growth stopped after 1998 and the

authorities had no instruments at their disposal with which to stimulate

the economy.

42

The other big disappointment has been Brazil. The largest economy in

the region, Brazil has consistently failed to achieve its potential. Adjustment

and liberalization were delayed until the 1990s, so this harsh judgment may

prove premature. However, greater fiscal and monetary responsibility, low

inflation, trade and financial liberalization, and the promotion of DFI

have not yet enabled Brazil to shift to a higher long-run sustainable growth

rate.

43

The obstacles in Brazil are numerous. The rate of investment is held back

by low domestic savings, as in so many parts of Latin America and unlike in

Asia; foreign capital cannot be relied on to close the gap. High real interest

rates discourage borrowing by the private sector for productive purposes.

Exports responded only modestly to devaluation and remained less than

10 percent of GDP until 2004 (compared with more than 20 percent in

China at the end of the 1990s). Brazil’s income inequality, one of the worst

in the world, also acts as a brake on its economic performance, although this

is more controversial. At the very least, Brazil does not enjoy the benefits

such as high savings rates that are supposed to accompany an unequal

distribution of income.

The transition from ISI would have required greater attention to foreign

trade, with or without globalization. The reason is that Latin America

saw its share of world trade decline steadily after 1950 to the point where

it had reached a mere 3.5 percent in 1980 (much lower than its share of

world population). Although some of this decline could be attributed to a

specialization in primary products at a time when primary products trade

was growing less fast than total trade, it was also attributable to the relentless

anti-export bias associated with the inward-looking model of development.

The strategy to reverse the decline in world market share has had two

components. First has been the greater attention to the export sector

through policies designed to favor traded over nontraded goods and within

tradeables to favor exportables over importables. Second has been the desire

to diversify exports away from primary products toward manufactured

goods and even services.

42

SeeM.Mussa, Argentina and the Fund: From Triumph to Tragedy (Washington, DC, 2002).

43

The difficulties facing Brazil were compounded by the 1988 constitution creating state obligations

in the area of social security that were increasingly onerous. These could only be tackled through

constitutional reform, which became a priority for the government of President Lula (2003–).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

Globalization and the New Economic Model in Latin America 159

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

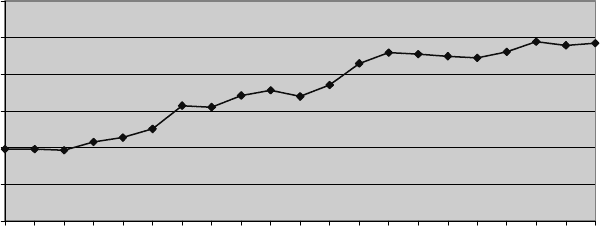

Figure 4.5.Diversification of Latin American exports, 1980–2000 (% of exports in

manufacturing).

Source: World Bank,WorldDevelopment Indicators 2002.

The results for Latin America as a whole have been impressive, although

they are heavily influenced by Mexico. Thus, the share of world exports

has indeed increased since the mid-1980s, but this is mainly because of

Mexico’s export boom. By 2000,Mexico accounted for half of all Latin

America’s exports. Excluding Mexico, the Latin American performance

has been much less satisfactory. However, some smaller countries – notably

Chile, but also Costa Rica – also increased world market share rapidly.

Aggregate figures for Latin America are always heavily influenced by

Brazil and trade is no exception. Thus, the poor performance of Latin

America (excluding Mexico) reflected the Brazilian export sector’s lack of

dynamism. This has been all the more puzzling in view of the increase in

export competitiveness after the devaluation in January 1999. The Brazilian

authorities tended to blame agricultural protectionism in rich countries for

this sad state of affairs, but in truth it has been much more complex.

The diversification of Latin America’s exports has been much more satis-

factory (see Figure 4.5). Once again, the results have been heavily influenced

by Mexico, but this time they are reinforced by Brazil. Yet in most countries,

the contribution of primary products to total exports has been in decline

and it must be borne in mind that the statistics in Figure 4.5 do not include

service exports.

Diversification has had several causes. In smaller countries, it has been

helped by the growth of the maquila industry. Haiti, for example, has one

of the lowest ratios of primary products to total exports and this is entirely

attributable to the assembly plants exporting light manufactures to the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

160 Victor Bulmer-Thomas

0

30

60

90

120

150

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

Argentina

Brazil

Mexico

Latin

America

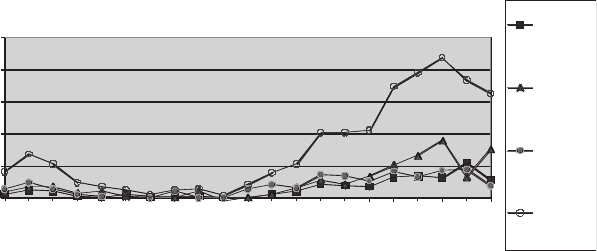

Figure 4.6.Net private capital flows, 1980–2000 (US$ billion).

Source: World Bank,WorldDevelopment Indicators 2002.

United States. In Costa Rica, the establishment by Intel of a computer-

chip factory at the end of the 1990s doubled the gross value of exports

within two years. In larger countries, it also reflects investments by MNCs

as part of the production chain linking subsidiaries across the world.

Regional integration has also been an important cause of diversification.

The new phase of integration has encouraged the export of manufactured

goods to neighboring countries. Indeed, despite the absence of formal dis-

crimination against agricultural products, almost all intraregional trade in

Latin America is in manufactures and a growing proportion of this is intra-

industry trade as well. However, the impact of regional integration would

appear to be quite limited because each scheme – with the notable exception

of NAFTA – has found it difficult to increase the share of total trade that

is intraregional. This peaked at 20 percent in MERCOSUR, 15 percent in

the CACM, and 10 percent in the Andean Community and CARICOM.

Capital account liberalization and other measures have helped to bring

foreign investment to Latin America. There has been a big increase in

net private capital flows to the region (see Figure 4.6), which once again

reflects the size and importance of the main economies (not only Brazil

and Mexico, but this time also Argentina). These annual flows help explain

the big increase in total external debt, which, by 2000, had reached nearly

$800 billion (see Figure 4.4). Considering that the stock of debt had been

“only” $258 billion in 1980, shortly before the debt crisis was triggered, and

that the economic performance after 1980 was far from stellar, it is clear

that the increase in debt was neither justified nor sustainable.

DFI was not attracted to Latin America in the 1980s. However, that

changed in the 1990s and by the end of the decade, the annual flow had

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c04 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 10:4

Globalization and the New Economic Model in Latin America 161

increased significantly and accounted for two thirds of the inflow of net

private capital. As a result, DFI raised its contribution to domestic invest-

ment from less than 5 percent in 1980 to nearly 20 percent in 2000.

44

This

ratio, similar to what is found in Southeast Asia, has been welcomed by

governments in the region, but it came too late to prevent the build-up

of the external debt. This now hangs like an albatross around the Latin

American neck. Only a handful of countries (Bolivia, Haiti, Honduras,

and Nicaragua) qualify for the relief developed for highly indebted poor

countries (HIPC) by the international creditors; for the larger countries,

HIPC is irrelevant because it does not apply to debt owed to the private

sector.

The most impressive Latin American performance has been in terms

of inflation stabilization. This has been a success story with only minor

qualifications,

45

as Table 4.2 makes clear. Given the long history of chronic

inflation in many countries before 1980, this is all the more remarkable.

Furthermore, the impact of adjustment programs in the 1980satfirst exac-

erbated inflationary pressures through the impact of currency depreciation,

increases in sales taxes, and ending of subsidies on the price level.

The fall in inflation rates at the beginning of the 1990s was mainly

attributable to real exchange rate appreciation. The inflows of capital led

to currency overvaluation that reduced inflation, but undermined exter-

nal competitiveness at the same time. The classic example is provided by

Argentina, where the rate of inflation fell from more than 50 percent a

month at the beginning of 1991 to an annual rate of less than 1 percent by

1996.

46

However, the cost in terms of lost competitiveness was high. The

real exchange rate appreciated by anything from 30 to 50 percent depending

on which domestic price deflator is used.

A fall in inflation caused by currency overvaluation is not sustainable. Yet,

inflation rates remained low even when real exchange rates depreciated. The

reasons were both economic and psychological. Tight fiscal and monetary

policies allowed the authorities to compensate for the impact of currency

falls, and trade liberalization lowered tariffs and increased competition in

the tradeable goods sector at the same time. However, inflation reduction

also had a psychological component. Inflationary expectations were broken

44

This ratio fell again, however, at the start of the new century, as a result of the decline in DFI to

Latin America.

45

The most important exception has been Venezuela, where inflation remained in double digits for

almost all of the period since the debt crisis.

46

Argentina even had price deflation between 1999 and 2001.SeeECLAC, Statistical Yearbook, 741.